Abstract

Strategies for blood management in the perioperative period of total joint replacement are changing with the better understanding of blood loss and blood replacement options in this population. The preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative options for blood management are outlined. Rationale for patient specific options are described.

INTRODUCTION

In this new millennium, the medical community in general and the orthopaedic surgeon specifically, have more scientific information available concerning the blood loss that occurs during and following total joint replacement of the lower extremity. In addition, better scientific data is available regarding the risks and benefits of various blood management options for patients. Also, newer pharmacologic and blood salvage options have been and are being developed. Finally, the medical community has obtained better data concerning the relationship of patient factors (including age, gender, comorbidities and hemoglobin levels) contributing to the blood management needs in the perioperative period. This paper will explore the various blood management options available for the orthopaedic surgeon and his or her patients when performing or undergoing total joint replacement. The preoperative planning of blood management needs will be outlined.

Blood Loss Following Total Hip or Total Knee Replacement Surgery

The blood loss associated with primary and revision total hip replacement and primary unilateral and bilateral total knee replacement has been extensively studied. In primary hip surgery the blood loss is 3.2 ± 1.3 units141 and 4.07 ± 1.74 grams of hemoglobin.24 Eighty seven per cent of patients lose less than 5.8 grams. In revision hip surgery the blood loss is approximately 4.0 ± 2.1 units. In primary knee replacement the blood loss ranges from 1000 to 1500 cc and averages 3.85 ± 1.4 grams of hemoglobin.24,71,101 87% of patients lose less than 5.25 grams of hemoglobin. Blood loss has been reported to be even higher in cementless knee replacement.57 In the perioperative period for bilateral total knee replacement the reported blood loss is 5.42 grams ± 1.8 gram24,71 with 87% of patients losing less than 7.22 grams. Blood loss may be greater for the second knee21 and alterations in coagulation have been noted. Transfusion rates of 2.0 ± 1.8 units for primary total hip replacement and 2.9 ± 2.3 units for revision hip replacement have been documented.8 The rates for knee replacement are not well studied but are estimated at 1 to 2 units for primary surgery and 3 to 4 units for revision surgery.

Several studies have documented the risk factors associated with the need for transfusion. 15,20,21,71,75,96,107,118,148 Preoperative hemoglobin level is a major predictor of the risk for transfusion following total joint replacement.9,15,32,37,40,43,55,71 Patients with a preoperative hemoglobin of less than 10 grams have a 90% chance of needing a transfusion, those with 10 to 13.5 gram level a 40-60% chance and those with greater than 13.5 grams a 15-25% chance. Other associated risk factors include blood volume, weight, age (patients less than 65 years with a hemoglobin greater than 13.5 had 3% risk of transfusion if they didn't autodonate blood),55 estimated blood loss, aspirin use, female sex, comorbidities, thrombocytopenia and bilateral total knee replacement.

In a study of a large number of patients (9482) undergoing total hip and knee replacement, 46% (57% hip, 39% knee) required a transfusion. The wasting rate of autologous units was 61% and 45% (highest in primary surgery and revision knee surgery.) Nine per cent of patients who autodonated blood required allogeneic transfusion (8% primary THA, 21% revision THA, 6% primary TKA, 11% revision TKA). The transfusion rate for patients with a hemoglobin of 10 to 13 (34% of all patients) was 57%. In this group, 33% of patients undergoing total hip replacement and 23% undergoing total knee replacement required allogeneic transfusion even though they donated autologous units. Predictors of allogeneic transfusion were baseline hemoglobin less than 13 grams and lack of autologous blood donation. Complications of allogeneic transfusion included infection and fluid overload (p ≤ .001) and increase in length of stay (p ≤ .01).

Options for Blood Management in the New Millennium

Allogeneic transfusion is a potential option for blood replacement in all patients. The risks of allogeneic transfusion are listed in Table 1 and comparative mortality risks are listed in Table 2. Other risks of allogeneic transfusion include clerical error (1:20,000-24,000), bacterial contamination, infection, immunomodulation, increase length of stay, and increased cost.

TABLE 1. Allogeneic Transfusion Risks.

| COMPLICATION | RISK PER UNIT |

|---|---|

| Minor allergic reactions | 1:100 |

| Bacterial Infection | 1:2500 |

| Viral Hepatitis | 1:5000 |

| Transfusion related lung injury | 1:5000 |

| Hemolytic Reaction | 1:6000 |

| Hepatitis B | 1:63,000 |

| Hepatitis C | 1:103,000 |

| HIV/AIDS | 1:500,000 |

| Anaphylaxis | 1:500,000 |

| Fatal Hemolytic Reaction (ABO incompatibility) | 1:600,000 |

| HTLV I/II Infection | 1:641,000 |

| GVHD | RARE |

| Immunomodulation | UNKNOWN |

TABLE 2. Comparative Mortality Risks.

| One pack per day of tobacco | 1:200 |

| Influenza | 1:5000 |

| Automobile deaths | 1:6000 |

| Frequent flying academic physician | 1:20,000 |

| Leukemia | 1:50,000 |

| Birth control pills | 1:50,000 |

| Tornadoes in Midwest | 1:445,000 |

| Floods | 1:455,000 |

| Earthquakes in California | 1:558,000 |

The goal of a blood management program is to reduce exposure to allogeneic blood, reduce the overall need for transfusion, eliminate transfusion related complications, 5,15,18,19,25,38,39,46,69,74,81,99,123,130,142 reduce cost, and develop a global strategy for blood management which is individualized and based on risk.24,27,46,71,77,78,104,107,125 In addition, if possible, the blood management program should improve medical and functional outcome. Along this path recent investigators have evaluated postoperative vigor72 in relationship to facilitated recovery, shortened length of stay, improved short term and long term physical function.

Strategies have been developed to reduce transfusion and the complications of transfusion during and following total hip and knee replacement. Practice guidelines include good hemostatic technique, preoperative autologous blood donation, intraoperative and postoperative blood salvage, acute normovolemic hemodilution, unit by unit transfusion based on individual needs and pharmacologic intervention when indicated. Blood loss can be reduced103 by preoperative, intraoperative, and postoperative measures. Preoperatively anti-platelet agents and anticoagulants should be eliminated when possible, bleeding history should be obtained, appropriate laboratory screening (CBC, platelets, coagulation studies, and bleeding time if indicated) should be performed, and a rationale approach to predonated autologous blood donation should be instituted considering preoperative risk factors and estimates of blood needs.9,55,78,81,107 Intraoperatively blood loss can be minimized by proper anesthetic techniques, pharmacologic intervention and surgical technique. Anesthetic techniques124,129 include hypotensive anesthesia, regional anesthesia23,31 and euthermia.121,122 Pharmacologic techniques include topical agents (thrombin, fibrin glue, collagen, Gelfoam, Avitene, epinephrine sponges and bone wax) and systemic antifibrinolytics (Desmopressin,67 Aprotinin,56,66,98,140 tranexamic acid11–13,62,63 and E-aminocaproic acid92). Postoperative measures include reduced phlebotomy, careful anticoagulation, nutrition, wound compression, and potentially avoiding continuous passive motion84,112,151 and drains.2,10,53,64,111,116,117,119 In addition, arbitrary transfusion triggers should be avoided.25,44,46,106,135,136 The surgeon should transfuse for symptoms instead and assess the patient for his or her physiologic risk from anemia. Hemoglobin levels as low as 8 are tolerated in the elderly without consequences23 and between 7 and 9 even in patients in critical care units without acute cardiac disease.60 Blood should be transfused unit by unit as needed. Patients with known cardiac disease and risk factors for morbidity from anemia25, 83,136 should be transfused earlier. Lower hemoglobins can be accepted in women due to lower hemoglobin starting point.46

Specific Alternatives to Allogeneic Transfusion

Preoperative autologous blood donation continues to be the current standard alternative to accepting allogeneic transfusion during and following total joint replacement. 1,17,47,50,126,137,139,143,147–149 Typically 1 or 2 units are obtained for primary joint replacement, 3 to 5 units for bilateral total joint replacement and 4 to 6 units for revision total joint replacement. The technique is indicated for patients with a hemoglobin greater than 11 and a hematocrit greater than 33. Units are drawn at 5 to 7 day intervals with the last unit drawn at least 3 days prior to surgery. Maximizing the time between the last unit and surgery increases the starting hemoglobin. Each unit removes about 500 cc or 9% of the blood volume of the average 70 kilogram man, hence supplemental iron should be provided. Contraindications include infection, unstable cardiovascular diseases and unacceptable anemia. Risks and complications47,81,113 include the poor endogenous erythropoietin response in patients with mild anemia leading to an increase in preoperative anemia,68,73,82 poor tolerance in the elderly to the donation process, bacterial contamination, wastage of unused blood9,15,33,40,47,55,75 and potential increased risk of transfusion and allogeneic blood exposure.9,27,55,126,138

Preoperative autologous donation decreases hemoglobin by 1.2 – 1.5 grams/dl. The advantages of this technique include the reduction in perioperative allogeneic blood exposure6,15,126 hence eliminating the risks of allogeneic blood transfusion.19,58 Recent studies have also demonstrated a potential reduction in the risk of postoperative deep venous thrombosis in total knee3 and total hip procedures.8

An alternative or adjunct to preoperative autologous blood donation is perioperative blood salvage. Intraoperative blood salvage has been shown to be beneficial in cases involving more than 1000 cc of blood loss.42,80,92,122,124,132,144 Sixty per cent of intraoperative blood loss124 can be salvaged and 400 to 500 cc of salvaged blood is required for reinfusion. The blood cells that are salvaged are altered (by irrigation, air, cement) and careful washing is important to avoid coagulopathy.88,100,143 It is not cost effective in primary arthroplasty if preoperative autologous donation is used. Postoperative salvage and reinfusion drainage systems are also available using washed or unwashed and filtered cells. 14,22,26,28,29,36,41,51,54,59,61,76,86,87,127,128,131,145,146,148,150 Postoperative wound drainage is collected and reinfused. Complications of unwashed reinfusion have included hypertension, hyperthermia, upper airway edema, coagulopathy100,133, febrile reaction, transfusion of byproducts of hemolysis and intraoperative contaminants133 and even death. Blood can only be collected for 4 to 6 hours thus limiting reinfusion to 500 to 1000 cc. The advantages of this technique are that significant amounts of blood can be retrieved and reinfused. Postoperative blood salvage can reduce allogeneic blood transfusion exposure if no autologous blood is available, 7,75,105 and further reduce allogeneic exposure when autologous blood is available.150

Another option for avoiding allogeneic blood transfusion is normovolemic or hypervolemic hemodilution. 30,47,93,95,109,110,122 With acute normovolemic hemodilution blood is collected immediately preoperatively by the anesthesiologists and stored for reinfusion postoperatively. The volume removed is repleted with crystalloid and colloid. Hypervolemic hemodilution is performed without phlebotomy only using crystalloid. The rationale for this approach is that blood that is lost at surgery will have a lower hematocrit and that the cells and blood that is retransfused is healthier. Indications, as with the other described techniques, are in cases with expected significant blood loss (such as total joint replacement). The patient must be healthy enough to tolerate acute anemia. Risks include the time consuming nature of the procedure and the procedure is contraindicated in patients with coronary artery, renal, pulmonary and hepatic disease.30 The advantages of this technique24,47,122 include reduction in perioperative allogeneic blood exposure110 (particularly if combined with other autologous blood use strategies109), reduced cost (no inventory or testing costs, no patient costs associated with procurement), and the reduced risk of clerical error (blood never leaves the room).

The other option in blood management is to increase hematopoiesis with pharmaceutical intervention. This has routinely been done by administering iron to those patients donating blood. However a much more effective way to increase hematopoiesis is the administration of erythropoietin alpha, a recombinant human erythoropoietin.16,32,34,35,43,45,49,52,65,79,89–92,94,120,134,138 Erythropoietin stimulates the differentiation of progenitor cells to become dedicated to the red blood cell line. The recombinant form mimics the physiologic action of endogenous erythropoietin glycoprotein hormone. In this technique, weekly injections (600 units/Kg) are given preoperatively on day 21, 14, and 7 as well as on the day of surgery. Alternately, the drug can be given daily for 10 days (300 units/Kg) followed by 4 days postoperatively. Adequate levels of iron must be maintained.34,48 The technique is presently indicated for patients with hemoglobin levels of 10 to 13, those unable or unwilling to undergo preoperative autologous blood deposit, bilateral and revision cases and patients that are Jehovah's Witnesses.102,134 The advantages of this approach are that it augments the number and quality of preoperative autologous deposited units45,108,114,115, and maximizes perioperative hemoglobin,138 particularly in comparison to matched populations of autologous donors. Preoperatively, postoperatively, and at discharge, hemoglobin levels were higher in the erythropoietin alpha group compared to the preoperative autologous donation group. Recently, it has been shown to improve postoperative vigor.72 Especially in patients with preoperative hemoglobin levels of 10 to 13 grams it significantly reduced transfusion risk (16 versus 45%). In this study hemoglobin level was directly proportional to readiness to resume activities of daily living and muscle strength. Improved hemoglobin enhanced the postoperative recuperative power (vigor and functional ability) and ability to participate in early intensive rehabilitation, thereby minimizing length of stay.97 Other advantages of erythropoietin alpha are that it stimulates an accelerated response to anemia4 and significantly reduces allogeneic blood exposure even in revision and bilateral surgery. The disadvantages of the drug are that it is injectable and expensive.

Patient Specific Transfusion Options

With all of the data available today concerning the blood loss associated with primary and revision total joint replacement, as well as the costs, benefits, and risks associated with the various blood management options and a better understanding of patient specific factors (such as the individual's blood volume and preoperative hemoglobin status), orthopaedic surgeons can better outline and implement blood management strategies for their patients. Although costs of allogeneic blood and autologous donation are hospital specific, autologous blood donation is considered more expensive and is bundled into the DRG of the procedure (Medicare part A) without additional reimbursement.152 In addition, wastage has been documented in up to 80 percent of cases.9,15,33,40,55,75

When developing a cost effective strategy for blood management it should be based on patient risk. The goal should be to minimize morbidity to the patient including minimization of preoperative and postoperative anemia, transmission of disease from transfusion and avoiding other morbidities from allogeneic or autologous transfusion. In addition, maximum functional outcome and postoperative vigor should be maintained and cost should be minimized. Waste and inappropriate use of technology should be avoided. Utilization of resources should be tailored to the documented needs of the patients.

Individual patient risk of transfusion should be assessed. Transfusion trigger should be determined based on the minimum hemoglobin that is acceptable given the patient's health, age and risk factors. The estimated blood loss should be determined (and this is probably surgeon and anesthesia dependent). The acceptable blood loss which will avoid transfusion trigger should be determined. Starting hemoglobin and patient weight and blood volume (males 65 to 70 cc blood/kg lean body weight, females 55 to 65 cc blood/kg lean body weight) are the important factors in this determination. An acceptable risk of allogeneic exposure should be chosen.

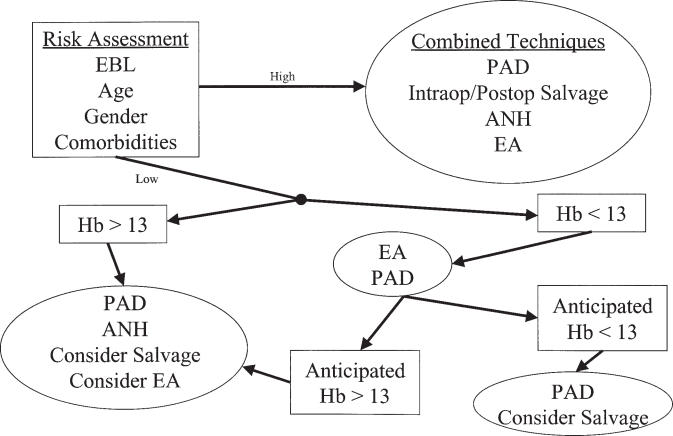

Algorithms for blood management in total joint replacement (Figure 1) have been developed. 9,24,27,40,47,55,71,77,78,81,85,104,107,125 The goal is to minimize transfusion by instituting institutional guidelines for transfusion,6,44,69,70 reducing transfusion triggers, utilizing aggressive strategies to reduce blood exposure and blood loss, and using marrow stimulants such as erythropoietin. Patients are categorized as high risk for transfusion (i.e. difficult revision surgery) or low risk (i.e. routine primary hip or knee replacement). If a patient is low risk and has a hemoglobin above 13 grams, he or she and the surgeon may decide on predeposit autologous donation, normovolemic hemodilution, intraoperative and postoperative salvage or erythropoietin alpha. If the patient is low risk with a preoperative hemoglobin less than 13, the options include erythropoietin alpha or autologous donation (if the patient's hemoglobin is greater than 11). Since the need for transfusion in patients with a hemoglobin of 10 to 13 grams is high even with predeposit autologous blood we consider erythropoietin alpha (33% for primary hips and 23% primary knees). If following this therapy the anticipated hemoglobin is still less than 13, intraoperative salvage or additional autologous blood donation (if the hemoglobin is above 11) can be considered.

Figure 1. ALGORITHM FOR BLOOD MANAGEMENT IN TJA.

Proposed algorithm for blood management in total joint replacement. (Estimated Blood Loss, EBL; Preoperative Autologous Donation, PAD; Acute Normovolemic Hemodilution, ANH; Erythropoietin alpha, EA; Hemoglobin (gm/dl), Hb)

SUMMARY

In summary, total joint arthroplasty results in significant blood loss. Patients undergoing total joint replacement are at significant risk for transfusion. There has been a paradigm shift to reducing the need for its inevitability and to improving perioperative blood management to maximize hemoglobin and positively impact early and long term outcome. This requires preoperative risk assessment, preoperative preparation, optimizing operative technique, and proper postoperative management as outlined in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Standards for blood banks and transfusion services. 17. Bethesda: American Association of Blood Banks; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acus R Wd, Clark JM, Gradisar IA, Jr, et al. The use of postoperative suction drainage in total hip arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1992;15:1325–1328. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19921101-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anders MJ, Lifeso RM, Landis M, et al. Effect of preoperative donation of autologous blood on deep-vein thrombosis following total joint arthroplasty of the hip or knee. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1996;78:574–580. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199604000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Atabek U, Alvarez R, Pello MJ, et al. Erythropoetin accelerates hematocrit recovery in post-surgical anemia. The American Surgeon. 1995;61:74–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.AuBuchon JP, Birkmeyer JD, Busch MP. Safety of the blood supply in the United States: opportunities and controversies. Ann Intern Med. 1997;127:904–909. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-127-10-199711150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Audet A, Andrzejewski C, Popovsky M. Red blood cell transfusion practices in patients undergoing orthopedic surgery: A multi-institutional analysis. Orthopedics. 1998;21:851–858. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19980801-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ayers DC, Murray DG, Duerr DM. Blood salvage after total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1995;77:1347–1351. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199509000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bae H, Westrich G, Sculco T, et al. Effect of preoperative donation of autologous blood on deep venous thromboembolism in total hip arthroplasty. Arthroplasty. 1999;14:252–253. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baranko B, Benjamin J. Blood utilization in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty. 64th annual meeting of AAOS; San Francisco. 1997. Paper 264. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beer K, Lombardi A, Mallory T, et al. The efficacy of suction drains after routine total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1991;73:584–587. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Benoni G, Carlsson A, Petersson C, et al. Does tranexamic acid reduce blood loss in knee arthroplasty? Am J Knee Surg. 1995;8:88–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Benoni G, Fredin H. Fibrinolytic inhibition with tranexamic acid reduces blood loss and blood transfusion after knee arthroplasty: a prospective, randomised, double-blind study of 86 patients. J Bone Joint Surg. (B) 1996;78:434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Benoni G, Lethagen S, Fredin H. The effect of tranexamic acid on local and plasma fibrinolysis during total knee arthroplasty. Thromb Res. 1997;85:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berman AT, Levenberg RJ, Tropiano MT. Postoperative autotransfusion after total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1996;19:15–22. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19960101-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berman BE, Callaghan JJ, Galante JO, et al. An analysis of blood management in patients having a total hip or knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1999;81:2–10. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199901000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Biesma DH, Marx JJ, Kraaijenhagen RJ, et al. Lower homologous blood requirement in autologous blood donors after treatment with recombinant human erythropoietin. Lancet. 1994;344:367–370. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91401-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Biesma DH, Marx JJ, van de Wiel A. Collection of autologous blood before elective hip replacement. A comparison of the results with the collection of two and four units. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1994;76:1471–1475. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199410000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blumberg N, Heal J. Immunomodulation by blood transfusion: an evolving scientific and clinical challenge. Am J Med. 1996;101 doi: 10.1016/S0002-9343(96)00124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Blumberg N, Kirkley SA, Heal JM. A cost analysis of autologous and allogeneic transfusions in hip-replacement surgery. Am J Surg. 1996;171:324–330. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9610(97)89635-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borghi B, Pignotti E, Montebugnoli M, et al. Autotransfusion in major orthopaedic surgery: experience with 1785 patients. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:662–664. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.5.662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bould M, Freeman B, Pullyblank A, et al. Blood loss in sequential bilateral total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:77–79. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90078-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bovill DF, Moulton CW, Jackson WS, et al. The efficacy of intraoperative autologous transfusion in major orthopedic surgery: a regression analysis. Orthopedics. 1986;9:1403–1407. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19861001-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carson J, Duff A, Berlin J, et al. Perioperative blood transfusion and postoperative mortality. JAMA. 1998;279:199–205. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.3.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Carson J, Goodnough L, Keating E. Blood products: Maximal use, conservation pre-deposit blood, when to transfuse and Erythropoietin. Course 128; 66th Annual Meeting of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons; Anaheim, CA. 1999. Presented at Instructional Course Lectures. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carson JL, Chen AY. In search of the transfusion trigger. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:30–35. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Clements DH, Sculco TP, Burke SW, et al. Salvage and reinfusion of postoperative sanguineous wound drainage. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1992;74:646–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cohen J, Brecher M. Preoperative autologous blood donation: benefit or detriment? A mathematical analysis. Transfusion. 1995;35:640–644. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35895357894.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dalen T, Brostrom LA, Engstrom KG. Autotransfusion after total knee arthroplasty. Effects on blood cells, plasma chemistry, and whole blood rheology. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:517–525. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90174-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dalen T, Brostrom LA, Engstrom KG. Cell quality of salvaged blood after total knee arthroplasty. Drain blood compared to venous blood in 32 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1995;66:329–333. doi: 10.3109/17453679508995555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Ambra M, Kaplan D. Alternatives to allogeneic blood use in surgery: acute normovolemic hemodilution and preoperative autologous donation. Am J Surg. 1995;23(Supplement 6A):49S–52S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80059-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dauphin A, Raymer KE, Stanton EB, et al. Comparison of general anesthesia with and without lumbar epidural for total hip arthroplasty: effects of epidural block on hip arthroplasty. J Clin Anesth. 1997;9:200–203. doi: 10.1016/s0952-8180(97)00035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.de Andrade J, Jove M, Landon G, et al. Baseline hemoglobin as a predictor of risk of transfusion and response to Epoetin alfo in orthopedic surgery patients. Am J Orthop. 1996;25:533–542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Etchason J, Petz L, Keeler E, et al. The cost effectiveness of preoperative autologous blood donations. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:719–724. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199503163321106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Faris PM, Ritter MA. Epoetin alfa. A bloodless approach for the treatment of perioperative anemia. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:60–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Faris PM, Ritter MA, Abels RI The American Erythropoietin Study Group. The effects of recombinant human erythropoietin on perioperative transfusion requirements in patients having a major orthopaedic operation. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1996;78:62–72. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199601000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Faris PM, Ritter MA, Keating EM, et al. Unwashed filtered shed blood collected after knee and hip arthroplasties. A source of autologous red blood cells. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1991;73:1169–1178. published erratum appears in J Bone Joint Surg Am 1991 Dec;73(10):1580. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Faris PM, Spence RK, Larholt KM, et al. The predictive power of baseline hemoglobin for transfusion risk in surgery patients. Orthopedics. 1999;22:S135–S140. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19990102-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandez M, Gottlieb M, Menitove J. Blood transfusion and postoperative infection in orthopedic patients. Transfusion. 1992;32:318–322. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32492263444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fiebig E. Safety of the blood supply. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:6–18. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Friedman R, Zimlich R, Butler J, et al. Preoperative hemoglobin as a predictor of transfusion risk in total hip and knee arthroplasty. 65th annual meeting of AAOS; 1998; New Orleans. Paper 381. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gannon DM, Lombardi AV, Jr, Mallory TH, et al. An evaluation of the efficacy of postoperative blood salvage after total joint arthroplasty. A prospective randomized trial. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6:109–114. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(11)80004-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gargaro JM, Walls CE. Efficacy of intraoperative autotransfusion in primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1991;6:157–161. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(11)80011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goldberg M, McCutchen J, Jove M, et al. A safety and efficacy comparison study of two dosing regimens of Epoetin alfa in patients undergoing major orthopedic Surgery. Am J Orthop. 1996;25:544–552. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Goodnough L, Depotis G. Establishing practice guidelines for surgical blood management. Am J Surg. 1995;170:16S–20S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80053-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodnough L, Rudnick S, Price T, et al. Increased preoperative collection of autologous blood with recombinant human erythropoietin therapy. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:1163–1168. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198910263211705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Goodnough LT, Brecher ME, Kanter MH, et al. Transfusion medicine. First of two parts—blood transfusion. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:438–447. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goodnough LT, Brecher ME, Kanter MH, et al. Transfusion medicine. Second of two parts—blood conservation. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:525–533. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902183400706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodnough LT, Monk TG. Erythropoietin therapy in the perioperative setting. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:82–88. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Goodnough LT, Monk TG, Andriole GL. Erythropoietin therapy. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:933–938. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199703273361307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Goulet J, Bray T, Timmerman L, et al. Intraoperative autologous transfusion in orthopaedic patients. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1989;71:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Groh GI, Buchert PK, Allen WC. A comparison of transfusion requirements after total knee arthroplasty using the Solcotrans autotransfusion system. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5:281–285. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(08)80084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.COPES Group, authors. Effectiveness of perioperative recombinant human erythropoietin in elective hip replacement. Lancet. 1993;341:1227–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hadden WA, McFarlane AG. A comparative study of closed-wound suction drainage vs no drainage in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1990;5(Suppl):S21–S24. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(08)80021-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Han CD, Shin DE. Postoperative blood salvage and reinfusion after total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:511–516. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90173-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hatzidakis A, Mendlick R, McKillip T, et al. The effect of preoperative autologous donation and other factors on the frequency of transfusion after total joint arthroplasty. 65th annual meeting of AAOS; 1998; New Orleans. Paper 382. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hayes A, Murphy DB, McCarroll M. The efficacy of single-dose aprotinin 2 million KIU in reducing blood loss and its impact on the incidence of deep venous thrombosis in patients undergoing total hip replacement surgery. J Clin Anesth. 1996;8:357–360. doi: 10.1016/0952-8180(96)00080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hays M, Mayfield J. Total blood loss in major joint arthroplasty. A comparison of cemented and noncemented hip and knee operations. J Arthroplasty. 1988. pp. S47–S49. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Healy JC, Frankforter SA, Graves BK, et al. Preoperative autologous blood donation in total-hip arthroplasty. A cost-effectiveness analysis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1994;118:465–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Healy WL, Pfeifer BA, Kurtz SR, et al. Evaluation of autologous shed blood for autotransfusion after orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop. 1994;299:53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hebert PC, Wells G, Blajchman MA, et al. A multicenter, randomized, controlled clinical trial of transfusion requirements in critical care. Transfusion Requirements in Critical Care Investigators, Canadian Critical Care Trials Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:409–417. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199902113400601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Heddle NM, Brox WT, Klama LN, et al. A randomized trial on the efficacy of an autologous blood drainage and transfusion device in patients undergoing elective knee arthroplasty. Transfusion. 1992;32:742–746. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32893032102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hiippala S, Strid L, Wennerstrand M, et al. Tranexamic acid (Cyklokapron) reduces perioperative blood loss associated with total knee arthroplasty. Br J Anaesth. 1995;74:534–537. doi: 10.1093/bja/74.5.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hiippala ST, Strid LJ, Wennerstrand MI, et al. Tranexamic acid radically decreases blood loss and transfusions associated with total knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1997;84:839–844. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199704000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Holt BT, Parks NL, Engh GA, et al. Comparison of closed-suction drainage and no drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1997;20:1121–1124. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19971201-05. discussion 1124-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jafari-Fesharaki M, Toy P. Effect and cost of subcutaneous recombinant human Erythropoietin in preoperative patients. Orthopedics. 1997;20:1159–1165. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19971201-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Janssens M, Joris J, David J, et al. High-dose aprotinin reduces blood loss in patients undergoing total hip replacement surgery. Anesthesiology. 1994;80:23–29. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199401000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Karnezis TA, Stulberg SD, Wixson RL, et al. The hemostatic effects of desmopressin on patients who had total joint arthroplasty. A double-blind randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1994;76:1545–1550. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199410000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kasper S, Gerlich W, Buzello W. Preoperative red cell production in patients undergoing weekly autologous blood donation. Transfusion. 1997;37:1058–1062. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.371098016445.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Keating E. Current options and approaches for blood management in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1998;80:750–762. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Keating EM. Current options and approaches for blood management in orthopaedic surgery. Instr Course Lect. 1999;48:655–665. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Keating EM, Meding JB, Faris PM, et al. Predictors of transfusion risk in elective knee surgery. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:50–59. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Keating EM, Ranawat CS, Cats-Baril W. Assessment of postoperative vigor in patients undergoing elective total joint arthroplasty: a concise patient- and caregiver-based instrument. Orthopedics. 1999;22:s119–s128. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19990102-04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kickler T, Spivak J. Effect of repeated whole blood donations on serum immunoreative erythropoietin levels in autologous donors. JAMA. 1988;260:65–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Klein H. Allogeneic tranfusion risks and the surgical patient. Am J Surg. 1995;170(Suppl):21S–26S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Knight J, Sherer D, Guo J. Blood transfusion strategies for total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1998;13:70–76. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(98)90077-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kristensen PW, Sorensen LS, Thyregod HC. Autotransfusion of drainage blood in arthroplasty. A prospective, controlled study of 31 operations. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992;63:377–380. doi: 10.3109/17453679209154748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Larocque B, Gilbert K, Brien B. Prospective validation of a point score system for predicting blood transfusion following hip or knee replacement. Transfusion. 1998;38:932–936. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.381098440857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Larocque BJ, Gilbert K, Brien WF. A point score system for predicting the likelihood of blood transfusion after hip or knee arthroplasty. Transfusion. 1997;37:463–467. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1997.37597293874.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Laupacis A. Effectiveness of perioperative epoetin alfa in patients scheduled for elective hip surgery. Semin Hematol. 1996;33:51–53. discussion 54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Law JK, Wiedel JD. Autotransfusion in revision total hip arthroplasties using uncemented prostheses. Clin Orthop. 1989;245:145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Lemos MJ, Healy WL. Blood transfusion in orthopaedic operations. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1996;78:1260–1270. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199608000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lorentz A, Eckardt K, Osswald P, et al. Erythropoietin levels in patients depositing autologous blood in short intervals. Ann Hematol. 1992;64:281–285. doi: 10.1007/BF01695472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Lotke P, Garino J, Barth P. Autogenous blood after total knee arthroplasty: Reduction in non-surgical complications. >64th annual meeting of AAOS; San Francisco. 1997. Paper 265. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lotke PA, Faralli VJ, Orenstein EM, et al. Blood loss after total knee replacement. Effects of tourniquet release and continuous passive motion. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1991;73:1037–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Manner PA, Rubash HE, Herndon JH. Prospectus. Future trends in transfusion. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:101–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Martin JW, Whiteside LA, Milliano MT, et al. Postoperative blood retrieval and transfusion in cementless total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1992;7:205–210. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(92)90019-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mauerhan DR, Nussman D, Mokris JG, et al. Effect of postoperative reinfusion systems on hemoglobin levels in primary total hip and total knee arthroplasties. A prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8:523–527. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.McKie J, Herzenberg J. Coagulopathy complicating intraoperative blood salvage in a patient who had idiopathic scoliosis. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1997;79:1391–1394. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199709000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mercuriali F. Epoetin alfa increases the volume of autologous blood donated by patients scheduled to undergo orthopedic surgery. Semin Hematol. 1996;33:10–12. discussion 13-4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Mercuriali F, Inghilleri G, Biffi E, et al. Erythropoietin treatment to increase autologous blood donation in patients with low basal hematocrit undergoing elective orthopedic surgery. Clin Investig. 1994;72:S16–S18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mercuriali F, Inghilleri G, Biffi E, et al. Comparison between intravenous and subcutaneous recombinant human erythropoietin (Epoetin alfa) administration in presurgical autologous blood donation in anemic rheumatoid arthritis patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Vox Sang. 1997;72:93–100. doi: 10.1046/j.1423-0410.1997.7220093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Mercuriali F, Zanella A, Barosi G, et al. Use of erythropoietin to increase the volume of autologous blood donated by orthopedic patients. Transfusion. 1993;33:55–60. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1993.33193142311.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Mielke LL, Entholzner EK, Kling M, et al. Preoperative acute hypervolemic hemodilution with hydroxyethylstarch: an alternative to acute normovolemic hemodilution? Anesth Analg. 1997;84:26–30. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199701000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Milbrink J, Birgegard G, Danersund A, et al. Preoperative autologous donation of 6 units of blood during rh-EPO treatment. Can J Anaesth. 1997;44:1315–1318. doi: 10.1007/BF03012783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Monk TG, Goodnough LT. Acute normovolemic hemodilution. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:74–81. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Monreal M, Lafoz E, Llamazares J, et al. Preoperative platelet count and postoperative blood loss in patients undergoing hip surgery: an inverse correlation. Haemostasis. 1996;26:164–169. doi: 10.1159/000217202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Munin M, Rudy T, Glynn N, et al. Early inpatient rehabilitation after elective hip and knee arthroplasty. JAMA. 1998;279:847–852. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.11.847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Murkin JM, Shannon NA, Bourne RB, et al. Aprotinin decreases blood loss in patients undergoing revision or bilateral total hip arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1995;80:343–348. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199502000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Murphy P, Heal J, Blumberg N. Infection of suspected infection after hip replacement surgery with autologous or homologous blood transfusions. Transfusion. 1991;31:212–217. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1991.31391165169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Murray D, Gress K, Weinstein S. Coagulopathy after reinfusion of autologous scavenged red blood cells. Anesth Analg. 1992;75:125. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199207000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Mylod A, France M, Muser D, et al. Perioperative blood loss associated with total knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1990;72:1010–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Nelson CL, Bowen WS. Total hip arthroplasty in Jehovah's Witnesses without blood transfusion. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1986;68:350–353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Nelson CL, Fontenot HJ. Ten strategies to reduce blood loss in orthopedic surgery. Am J Surg. 1995;170:64S–68S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80062-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Nelson CL, Fontenot HJ, Flahiff C, et al. An algorithm to optimize perioperative blood management in surgery. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:36–42. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Newman JH, Bowers M, Murphy J. The clinical advantages of autologous transfusion. A randomized, controlled study after knee replacement. J Bone Joint Surg. (B) 1997;79:630–632. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b4.7272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.NIH. Consensus conference: Perioperative red blood cell transfusion. JAMA. 1988;260:2700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nuttall GA, Santrach PJ, Oliver WC, Jr, et al. The predictors of red cell transfusions in total hip arthroplasties. Transfusion. 1996;36:144–149. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36296181927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Nydegger U. Enhanced efficacy of autologous blood donation with epoetin alfa. Semin Hematol. 1996;33:39–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Oishi CS, DL DD, Morris BA, et al. Hemodilution with other blood reinfusion techniques in total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1997;339:132–139. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199706000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Olsfanger D, Fredman B, Goldstein B, et al. Acute normovolaemic haemodilution decreases postoperative allogeneic blood transfusion after total knee replacement. Br J Anaesth. 1997;79:317–321. doi: 10.1093/bja/79.3.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ovadia D, Luger E, Bickels J, et al. Efficacy of closed wound drainage after total joint arthroplasty. A prospective randomized study. J Arthroplasty. 1997;12:317–321. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(97)90029-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pope RO, Corcoran S, McCaul K, et al. Continuous passive motion after primary total knee arthroplasty. Does it offer any benefits? J Bone Joint Surg. (B) 1997;79:914–917. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.79b6.7516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Popovsky M, Whitaker B, Arnold N. Severe outcomes of allogeneic and autologous blood donation: frequency and characterization. Transfusion. 1995;35:734–737. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35996029156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Price TH, Goodnough LT, Vogler WR, et al. The effect of recombinant human erythropoietin on the efficacy of autologous blood donation in patients with low hematocrits: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, controlled trial. Transfusion. 1996;36:29–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36196190512.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Price TH, Goodnough LT, Vogler WR, et al. Improving the efficacy of preoperative autologous blood donation in patients with low hematocrit: a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial of recombinant human erythropoietin. Am J Med. 1996;101:22s–27s. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Reilly TJ, Gradisar IA, Jr, Pakan W, et al. The use of postoperative suction drainage in total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1986;208:238–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ritter MA, Keating EM, Faris PM. Closed wound drainage in total hip or total knee replacement. A prospective, randomized study. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1994;76:35–38. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199401000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Robinson CM, Christie J, Malcolm-Smith N. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs, perioperative blood loss, and transfusion requirements in elective hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8:607–610. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(93)90007-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Rollo VJ, Hozack WJ, Rothman RH, et al. Prospective randomized evaluation of blood salvage techniques for primary total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:532–539. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(05)80157-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Sans T, Bofil C, Joven J, et al. Effectiveness of very low doses of subcutaneous recombinant human erythropoietin in facilitating autologous blood donation before orthopedic surgery. Transfusion. 1996;36:822–826. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.36996420762.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schmied H, Kurz A, Sessler DI, et al. Mild hypothermia increases blood loss and transfusion requirements during total hip arthroplasty. Lancet. 1996;347:289–292. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(96)90466-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Schmied H, Schiferer A, Sessler DI, et al. The effects of red-cell scavenging, hemodilution, and active warming on allogenic blood requirements in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty. Anesth Analg. 1998;86:387–391. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199802000-00032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Schreiber G, Busch M, Kleinman S, et al. The risk of transfusion transmitted viral infections. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1685–1690. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199606273342601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Sculco T. Blood management in orthopaedic surgery. Am J Surg. 1995;170:60S–63S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80061-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Sculco TP. Global blood management in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:43–49. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Sculco TP, Gallina J. Blood management experience: relationship between autologous blood donation and transfusion in orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 1999;22:s129–s134. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19990102-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Seidel H, Hertzfeldt B, Hallack G. Reinfusion of filtered postoperative orthopedic shed blood: safety and efficacy. Orthopedics. 1993;16:291–295. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930301-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Semkiw LB, Schurman DJ, Goodman SB, et al. Postoperative blood salvage using the Cell Saver after total joint arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1989;71:823–827. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sharrock NE, Salvati EA. Hypotensive epidural anesthesia for total hip arthroplasty: a review. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:91–107. doi: 10.3109/17453679608995620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Simpson M, Georgopoulos G, Orsini E, et al. Autologous transfusions for orthopaedic procedures at a children's hospital. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1992;74:652. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Simpson MB, Murphy KP, Chambers HG, et al. The effect of postoperative wound drainage reinfusion in reducing the need for blood transfusions in elective total joint arthroplasty: a prospective, randomized study. Orthopedics. 1994;117:133–137. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19940201-08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Slagis SV, Benjamin JB, Volz RG, et al. Postoperative blood salvage in total hip and knee arthroplasty. A randomised controlled trial. J Bone Joint Surg. (B) 1991;73:591–594. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B4.1906472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Southern EP, Huo MH, Mehta JR, et al. Unwashed wound drainage blood. What are we giving our patients? Clin Orthop. 1995;320:235–246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Sparling EA, Nelson CL, Lavender R, et al. The use of erythropoietin in the management of Jehovah's Witnesses who have revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1996;78:1548–1552. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199610000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Spence R. Surgical red blood cell transfusion practice policies. Am J Surg. 1995;170:3S–15S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(99)80052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Spence RK. Anemia in the patient undergoing surgery and the transfusion decision. A review. Clin Orthop. 1998;357:19–29. doi: 10.1097/00003086-199812000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Stanisavljevic S, Walker RH, Bartman CR. Autologous blood transfusion in total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1986;1:207–209. doi: 10.1016/s0883-5403(86)80032-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Stowell CP, Chandler H, Jove M, et al. An open-label, randomized study to compare the safety and efficacy of perioperative epoetin alfa with preoperative autologous blood donation in total joint arthroplasty. Orthopedics. 1999;22:S105–S112. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19990102-02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Thomson JD, Callaghan JJ, Savory CG, et al. Prior deposition of autologous blood in elective orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1987;69:320–324. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Thorpe CM, Murphy WG, Logan M. Use of aprotinin in knee replacement surgery. Br J Anaesth. 1994;73:408–410. doi: 10.1093/bja/73.3.408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Toy PT, Kaplan EB, McVay PA, et al. Blood loss and replacement in total hip arthroplasty: a multicenter study. The Preoperative Autologous Blood Donation Study Group. Transfusion. 1992;32:63–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1992.32192116435.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142.Vamvakas EC, Moore SB, Cabanela M. Blood transfusion and septic complications after hip replacement surgery. Transfusion. 1995;35:150–156. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1995.35295125738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143.Williamson K, Moore S, Santrach P. Transfusion and Bone Banking. In: Morrey B, editor. Reconstructive Surgery of the Joints. New York: Churchill-Livingstone; 1996. pp. 121–133. [Google Scholar]

- 144.Wilson WJ. Intraoperative autologous transfusion in revision total hip arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1989;71:8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145.Wixson RL, Kwaan HC, Spies SM, et al. Reinfusion of postoperative wound drainage in total joint arthroplasty. Red blood cell survival and coagulopathy risk. J Arthroplasty. 1994;9:351–358. doi: 10.1016/0883-5403(94)90044-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146.Woda R, Tetzlaff JE. Upper airway oedema following autologous blood transfusion from a wound drainage system. Can J Anaesth. 1992;39:290–292. doi: 10.1007/BF03008792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147.Woolson ST, Marsh JS, Tanner JB. Transfusion of previously deposited autologous blood for patients undergoing hip-replacement surgery. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1987;69:325–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148.Woolson ST, Pottorff G. Use of preoperatively deposited autologous blood for total knee replacement. Orthopedics. 1993;16:137–141. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19930201-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 149.Woolson ST, Watt JM. Use of autologous blood in total hip replacement. A comprehensive program. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1991;73:76–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 150.Xenakis TA, Malizos KN, Dailiana Z, et al. Blood salvage after total hip and total knee arthroplasty. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1997;275:135–138. doi: 10.1080/17453674.1997.11744767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 151.Yashar AA, Venn-Watson E, Welsh T, et al. Continuous passive motion with accelerated flexion after total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 1997;345:38–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 152.Yomtovian R, Kruskall M, Barber J. Autologous-blood transfusion: the reimbursement dilemma. J Bone Joint Surg. (A) 1992;74:1265. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]