Abstract

Objective To determine at what age children can perform effective chest compressions for cardiopulmonary resuscitation.

Design Observational study.

Setting Four schools in Cardiff.

Participants 157 children aged 9-14 years in three school year groups (ages 9-10, 11-12, and 13-14).

Interventions Participants were taught basic life support skills in one lesson lasting 20 minutes.

Main outcome measure Effectiveness of chest compression during three minutes' continuous chest compression on a manikin.

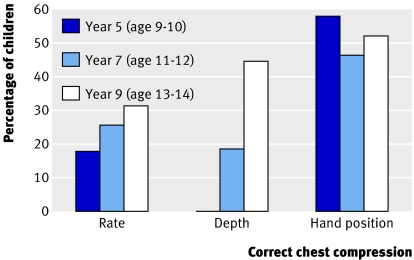

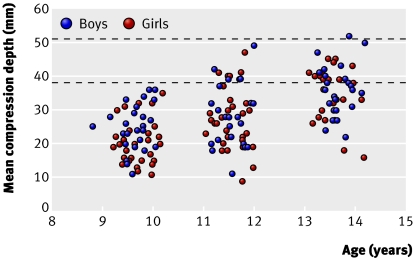

Results No year 5 pupil (age 9-10) was able to compress the manikin's chest to the depth recommended in guidelines (38-51 mm). 19% of pupils in year 7 (age 11-12) and 45% in year 9 (age 13-14) achieved adequate compression depth. Only the 13-14 year olds performed chest compression as well as adults in other reported studies. Compression depth showed a significant relation with children's age, weight, and height (P<0.001). Multivariate analyses showed that, if the age and weight of the children were both known, the height (which is closely related to both) was no longer significant (P=0.95). No association was found between pupils' age, sex, weight, or height and the average rate of chest compressions over the three minute period. Similarly, no relation was found between year group and ability to place the hands in the correct position. During the three minutes' compression, compression rate increased and depth decreased.

Conclusions The children's ability to achieve an adequate depth of chest compression depended on their age and weight. The ability to provide the correct rate and to employ the correct hand position was similar across all the age ranges tested. Young children who are not yet physically able to compress the chest can learn the principles of chest compression as well as older children.

Introduction

Resuscitation skills should be learnt at school,1 2 since children are easily motivated, learn quickly, and retain skills.3 4 After pioneering work in Norway, such training has been introduced in several countries.5 6 7 8 Skills are introduced successively according to children's cognitive and psychomotor development. In the United Kingdom a national syllabus and training programme, developed by the British Heart Foundation through “Heartstart UK,” introduces chest compression to schoolchildren at 11 years of age.

Studies of skill acquisition have concentrated on older children.3 4 9 No study reports when children are capable of the more physically demanding tasks, particularly chest compression. Recommended ages vary from 9 to 13.8 This study investigated when children can provide effective chest compressions.

Participants and methods

Participants

We recruited schoolchildren in year groups 5 (9-10 years old), 7 (11-12 years), and 9 (13-14 years) from four schools in Cardiff that had expressed interest in the Heartstart UK programme. The study was explained to parent and teacher groups, written consent being obtained from all parents and verbal consent from participating children. Children's weight, height, sex, and date of birth were recorded.

Training

Chest compressions were taught on a Laerdal Little Anne training manikin according to Heartstart UK schools training programme level 3 skill card 7a.10 Each child attended one training session lasting 20 minutes and was assessed within one hour of being trained. Each class consisted of four pupils and an instructor, with each pupil and the instructor having an individual training manikin.

Skills assessment

Children performed continuous chest compressions on a Laerdal Resusci Anne SkillReporter manikin for three minutes. The time remaining was announced every 30 seconds; no other audio or visual feedback was provided during the assessment.

Compression rate and depth and percentage with correct hand position were recorded with Laerdal PC SkillReporter software version 2.0. The software produced averages for compression rate and depth for the three minute assessment, and averages for each minute were calculated with software tools. Correct compression depth and rate were defined as 38-51 mm and 90-110 per minute.

Statistical analysis

To investigate associations between variables, we used parametric (Pearson) correlations, bivariate and multivariate linear regression, t tests, and χ2 tests.

The power calculation was based on a median of 82 satisfactory chest compressions (interquartile range 55-100) that had been achieved by adults on similar manikins.10 Applying this average to the mean rate achieved by children aged 13-14, we constructed a standard deviation of 33.4 from the interquartile range. Assuming the mean reduces by 30% at age 9-10 to 57.4 (SD 33.4), we calculated that 30 children in each age group would provide an 80% power to detect such a difference (α 5%). The power to show that children aged 11-12 differ from either of the other groups is lower, and in practice we recruited larger numbers.

Results

All the pupils performed three minutes of continuous chest compression. The table lists their characteristics and, with figures 1 and 2, their performance. Pupils' height and weight increased progressively in both sexes across successive year groups.

Physical characteristics of schoolchildren aged 9-14 years and the quality of chest compressions for cardiopulmonary resuscitation, by school year group

| School year | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Year 5 | Year 7* | Year 9 | |

| No of children (girls, boys) | 55 (28, 27) | 54 (31, 23) | 48 (24, 24) |

| Pupils' characteristics (mean (range) values): | |||

| Age (years) | 9.7 (9.2-10.2) | 11.6 (11.1-12.0) | 13.6 (13.1-14.2) |

| Height (cm) | 139 (123-153) | 149 (131-165) | 161 (146-184) |

| Weight (kg) | 35 (24-56) | 42 (26-70) | 54 (35-103) |

| Pupils' chest compression performance†: | |||

| Mean (SD) compression rate/min‡ | 108 (31) | 109 (26) | 116 (25) |

| Percentage who achieved the correct compression rate | 18 | 26 | 30 |

| Mean (SD) compression depth (mm)§ | 23 (6.9) | 28 (9.0) | 35 (7.8) |

| Percentage who achieved the correct compression depth | 0 | 19 | 45 |

| Percentage with 100% correct hand placement | 40 | 22 | 31 |

| Percentage with 80-100% correct hand placement | 58 | 46 | 52 |

*A bias of 31girls to 23 boys in Year 7 did not influence analysis.

†Means represent the average for entire 3 minute period.

‡No statistical relation to age (b=1.6 per year (95% CI −1.1 to 4.3)), P=0.233.

§Significant relation to age (b=3.2 per year (95% CI 2.4 to 4.0)), P<0.001.

Fig 1 Proportions of children in each school year group correctly performing chest compressions in terms of compression rate (90-110/min) and depth (38-51 mm) and correct hand positions for 80-100% of compressions

Fig 2 Scatter plot showing depth of chest compression achieved by children in each school year group. The correct compression depth is between the two dotted lines.

Compression rate—Average compression rate was not related to pupils' age, sex, weight, or height. A trend towards improvement in successive groups did not reach significance. The mean rate increased successively in each minute of the assessment period in all groups.

Compression depth—Adequate depth was achieved by no pupils in year 5, 19% in year 7, and 45% in year 9. The compression depth showed significant association with the pupils' age, weight, and height (P<0.001). However, multivariate analyses showed that, once age and weight were known, height (closely related to both) was no longer significantly associated (P=0.95). The mean compression depth decreased in successive minutes in all groups as compression rate increased, but the inverse relation between the two was not significant (r=−0.07, P=0.39).

Hand position—No relation existed between pupils' age and the proportion achieving correct hand position. Correct hand placement for 100% of compressions was achieved by 40% of pupils in year 5, 22% in year 7, and 31% in year 9. For 80-100% correct, the corresponding figures were 58%, 46%, and 52%.

Discussion

None of the children aged 9-10 years and only 19% of those aged 11-12 were strong enough to compress the chest to an adequate depth in simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation on an adult size manikin. However, 45% of those aged 13-14 provided adequate compression depth, a similar success rate to that achieved by adults tested in comparable studies.11 12 13 14 15 Current recommendations to teach full, single rescuer cardiopulmonary resuscitation at age 13-14 are therefore appropriate.

Comparison with other studies

Previous studies in schoolchildren have tested factual knowledge with questionnaires and assessed practical skills with manikins,3 4 9 Studies assessing practical ability have concentrated on older children and teenagers. Few assessed performance of chest compressions, concentrating instead on airway and breathing skills.16 Van Kerschaver assessed hand position and compression rate in children aged 12 years and older but did not report compression depth.3 Lester reported that children aged 11-12 often failed to compress the chest adequately, but did not report quantitative data.17

Compression depth declined in successive minutes, as in some adult studies, which have shown a decline in compression quality with time.10 18 19

Limitations of study

A manikin may offer greater or lesser resistance than a real casualty. Emotional factors in real life resuscitation may also affect performance. Quality of compression beyond three minutes was not assessed. Compressions given in cycles alternating with rescue breaths might be less accurate than continuous compressions.

Conclusions

In our study, children aged 9-10 years used the correct hand position and same compression rate as older children. Although they were not able to compress the chest sufficiently, they learnt the methods of performing chest compression as well as the older children. Teaching younger children provides knowledge for when they are adequately developed. They might also advise an adult or perform adequately on a chest more compliant than that of the manikin. By starting training young, revision is possible at school, with the prospect of greater skill attainment and retention.

What is already known on this topic

Bystander cardiopulmonary resuscitation at least doubles the chances of survival

Chest compressions receive increased prominence in current resuscitation guidelines

Schoolchildren are widely taught resuscitation techniques, but the age when they can perform effective chest compressions is unknown

What this study adds

Children aged 13-14 performed compressions as well as adults in comparable studies

Although younger children were not strong enough to compress the chest sufficiently, they learnt the theory of the technique just as well as older children

We thank the pupils and staff of Cardiff High School, Oakfield Primary School, Radyr Comprehensive School, and Ton-Yr-Ywen Primary School for their enthusiastic participation. We thank Richard Davies, chief education officer, Welsh Assembly Government, for his advice during the planning of this study. We thank Laerdal Medical for its support and advice and for the loan of a Laerdal Resusci Anne SkillReporter System. Lastly we thank those staff of the Welsh Ambulance Service who helped at all stages of the study.

Contributors: MC had the idea for the project and acts as guarantor. All authors contributed to the design of the project. IJ and RW carried out the study and collected the data. Data processing was by IJ and RN. IJ and MC wrote the first drafts of the paper; all authors contributed to the final version.

Funding: The study was funded by a grant from the British Heart Foundation. None of the authors receive payment or other financial incentive from the funding body. No pharmaceutical company was involved. There was no financial involvement by any medical equipment company.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Dyfed Powys Local Research Ethics Committee approved the study.

References

- 1.European Resuscitation Council. Introduction to the international guidelines 2000 for CPR and ECC. Resuscitation 2000;46:3-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on School Health. Basic life support training school. Pediatrics 1993;91:158-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Kerschaver E, Delooz HH, Moens GFG. The effectiveness of repeated cardiopulmonary resuscitation training in a school population. Resuscitation 1989;17:211-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eisenburger P, Safar P. Life supporting first aid training of the public—review and recommendations. Resuscitation 1999;41:3-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lind B. Teaching mouth to mouth resuscitation in primary schools. Acta Anaesth Scand 1961;9(suppl):63-9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.British Heart Foundation. Heartstart UK training pack for schools. Emergency life support skills for young people London: British Heart Foundation, 2003

- 7.Lafferty C, Larsen P, Galletly D. Resuscitation training in New Zealand schools. N Z Med J 2003;116:582-8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maternal and Child Health Bureau. Basic emergency lifesaving skills (BELS): a framework for teaching emergency lifesaving skills to children and adolescents Newton, MA: Children's Safety Network, Education Development Center, 1999

- 9.Plotnikoff R, Moore P. Retention of knowledge and skills in cardiopulmonary resuscitation of 11 and 12 year old children. Med J Aust 1989;150:296-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ashton A, McCluskey A, Gwinnutt CL, Keenan AM. Effect of rescuer fatigue on performance of continuous external chest compressions over 3 min. Resuscitation 2002;55:151-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Handley AJ, Handley SA. Improving CPR performance using an audible feedback system suitable for incorporation into an automated external defibrillator. Resuscitation 2003;57:57-62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wik L, Kramer-Johansen J, Myklebust H, Sorebo H, Svensson L, Fellows B, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2005;293:299-304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wik L, Thowsen J, Steen PA. An automated voice advisory manikin system for training in basic life support without an instructor. A novel approach to CPR training. Resuscitation 2001;50:167-72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abella BS, Alvarado JP, Myklebust H, Edelson DP, Barry A, O'Hearn N, et al. Quality of cardiopulmonary resuscitation during in-hospital cardiac arrest. JAMA 2005;293:305-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Woollard M, Smith A, Whitfield R, Chamberlain D, West R, Newcombe R, et al. To blow or not to blow: a randomised controlled trial of compression-only and standard telephone CPR instructions in simulated cardiac arrest. Resuscitation 2003;59:123-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore PJ, Plotnikoff RC, Preston GD. A study of school students' long term retention of expired air resuscitation knowledge and skills. Resuscitation 1992;24:17-25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lester C, Donnelly P, Weston C, Morgan M. Teaching schoolchildren cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Resuscitation 1996;31:33-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ochoa FJ, Ramalle-Gomara E, Lisa V, Saralegui I. The effect of rescuer fatigue on the quality of chest compressions. Resuscitation 1998;37:149-52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hightower D, Thomas SH, Stone CK, Dunn K, March JA. Decay in quality of closed-chest compressions over time. Ann Emerg Med 1995;26:300-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]