Abstract

Researchers have become increasingly interested in the social context of chronic pain conditions. The purpose of this article is to provide an integrated review of the evidence linking marital functioning with chronic pain outcomes including pain severity, physical disability, pain behaviors, and psychological distress. We first present an overview of existing models that identify an association between marital functioning and pain variables. We then review the empirical evidence for a relationship between pain variables and several marital functioning variables including marital satisfaction, spousal support, spouse responses to pain, and marital interaction. On the basis of the evidence, we present a working model of marital and pain variables, identify gaps in the literature, and offer recommendations for research and clinical work.

Perspective

The authors provide a comprehensive review of the relationships between marital functioning and chronic pain variables to advance future research and help treatment providers understand marital processes in chronic pain.

Keywords: Chronic pain, couples, spouse responses, depression, marital satisfaction, pain severity, disability

Researchers have become increasingly interested in the interpersonal nature of chronic illnesses including chronic pain.9,47 For instance, the existing literature indicates that couples’ reports of sexual and marital satisfaction often decline after the onset of a pain condition.28,54 Studies have also shown that relationship variables, such as marital satisfaction and spousal support, are associated with pain severity, physical disability, and depression in individuals with chronic pain (ICPs).11,14,46,60 In their review of the literature, Burman and Margolin9 found some evidence that marital status, satisfaction, and couples’ interactions related to chronic medical problems such as chronic pain, cardiovascular disease, and poor immune functioning. Another review by Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton47 focused on the physiologic effects of marital functioning that might relate to health outcomes including pain. Although both reviews are important works in the study of couples and health, the authors did not focus on theories specific to chronic pain, psychological comorbidity, or special issues involved in conducting chronic pain research. Furthermore, several studies have since been conducted in the pain field. In fact, no systematic review of the literature has focused solely on the associations between marital processes, pain severity, physical disability, and psychological distress experienced by ICPs or their spouses. Therefore, it is unclear whether consistent associations among these variables exist across studies. For instance, differences might exist depending on the measures used or chronic pain populations recruited. Also unclear is the degree to which existing models of pain including a focus on significant others are supported by the empirical evidence.

In this article, we provide an overview of existing models that explain the relationships between marital functioning and chronic pain outcomes. We also critically review the empirical literature to determine the extent to which the evidence does or does not support these models. We conclude by presenting an integrative model of marriage, pain, and depression that is supported or fully explored in the current literature. In addition, we identify the paths that have been suggested by models but have not yet been supported by the evidence. We expect that this review will provide new directions for research and clinical practice. We chose a qualitative review of the literature as opposed to a quantitative meta-analytic review, because the latter would necessitate that all studies use similar research designs, constructs, and statistical analyses.49 Furthermore, the studies would also need to focus on specific combinations of variables that would not allow a more comprehensive perspective that could be used to guide future research. Because these goals have not yet been achieved, we take a different approach in which we rate the quality of each study as well as the strength of support for various relationships. Throughout this review, we use the terms marriage or marital because the vast majority of articles reviewed here focused on heterosexual married couples. It is likely that similar findings will be found for heterosexual unmarried couples and same-sex couples; however, research is needed to support this hypothesis.

Couples Functioning in Models of Pain and Depression

Several theories suggest that marital and other romantic relationships might be important to consider when examining pain and disability in ICPs. Specifically, the operant model of pain suggests that pain behavior of ICPs might be rewarded or punished by persons with whom they have frequent interactions.31 Spouses or significant others might have the most opportunities for reinforcing pain behaviors because of the frequency of contact and intimacy of the relationship. Positive reinforcement behaviors could include attention or support provision when ICPs express pain. Well behaviors and activity might also be positively reinforced. Alternatively, ignoring or reacting negatively to the pain behavior might lead to a decrease or extinction of that behavior.

Cognitive-behavioral models of pain94 focus on ICPs’ appraisals of their pain and disability as contributors to the reduction or maintenance of the pain. For instance, ICPs who believe that they are unable to escape from the pain might become hopeless about the potential for recovery. Spouses’ own attitudes and beliefs about pain might influence their behaviors toward ICPs or the treatment itself, hence influencing ICPs’ cognitions, emotions, and behaviors. For instance, a significant other might not fully support or engage in treatment because they perceive that the pain is not a real problem. In turn, expressions of pain behavior by the ICP might escalate in an effort to convince the spouse that the pain is real. Couples might also engage in a “conspiracy of silence” in which ICPs might not verbally express pain, and the spouses might not verbally express that they can see the nonverbal pain responses.94 Although both spouses try not to upset the other, each might become distressed because of the lack of open communication about the interactions or changes that have taken place within the relationship.

Cognitive-behavioral models of pain emphasize the evaluation or interpretation of the pain experience. The Communal Coping Hypothesis92,93 is a recent attempt to clarify particular cognitions that are important in the pain process. Specifically, pain catastrophizing is a cognitive style in which there is an exaggerated and negative focus on the pain experience. According to the Communal Coping Hypothesis, some ICPs might catastrophize to elicit support and intimacy from significant others. An alternative interpretation is that ICPs’ appraisals about the threat value of pain (eg, catastrophizing) enable ICPs to cope in particular ways.89 This appraisal model might account for why catastrophizing might lead to the avoidance of activities.89,99 Whether pain catastrophizing cognitions are simply fear-related appraisals of pain or are also vehicles for ICPs to garner intimacy from others, several studies have shown that catastrophizing thoughts and related behaviors are associated with exacerbated pain and psychological distress.34,90,91,97,98

Researchers have begun to incorporate the various theories of chronic illness and interpersonal experience into integrative models of health. For instance, Turk and Kerns95 proposed a Transactional Model of Health. Although this model was initially developed for use with families suffering from general medical conditions, it is easily applicable to the study of couples and chronic pain. The Transactional Model is an integration of concepts from family systems, cognitive-behavioral models, and coping theories. Borrowing from the work of Lazarus and Folkman,48 this theory maintains that couples’ appraisals of any given situation and their available resources determine whether a situation is perceived as stressful. The couples’ reactions or coping efforts are also important in this model because they can improve or exacerbate stressors. Furthermore, emphasis is placed not only on ICPs or the relationship but also on each member’s influence on the other.

Other integrative models have also explained links between close relationships and chronic medical illnesses. Burman and Margolin9 suggested marital interactions might be beneficial (eg, support provision) or detrimental (eg, stressful interactions) for couple members. Together with other variables such as personal characteristics, stress and support might influence an individual’s psychological responses to any given situation. Similarly, Kiecolt-Glaser and Newton47 put forth a model that suggested that positive and negative marital functioning might relate to health outcomes such as functional status and pathophysiology through the effects of health habits, individual difference variables, and changes in cardiovascular, neurophysiologic, and other biologic systems.

Any review of theories concerning chronic pain would be incomplete without also addressing psychological distress, because depressive symptoms and disorders are highly comorbid with chronic pain and marital distress.2,11,14,28,46,67,72,96 Most models developed to describe the relationship between marital functioning and depression are based on cognitive-behavioral and interpersonal tenets.3,23,38 For instance, appraisals of marital dissatisfaction or discord might lead to depression because of decreased spousal reinforcement and increased hostility, as well as perceived losses in social support and coping assistance from the spouse.3 It is sensible that these same processes might occur in couples facing chronic pain. Although not identifying the marriage specifically, 2 models of comorbid chronic illness and psychopathology include social relationships as important risk factors. Cohen and Rodriguez22 suggested that there are several pathways through which chronic illness can lead to psychological comorbidity (and vice versa). They suggested that pain and physical disability, as well as other aspects of physical disorders, might contribute to depression through changes in biologic variables (eg, hormones, sleep), behaviors (eg, maladaptive coping), cognitions (eg, thought distortions), and social interaction (eg, deterioration of social networks).

More specific to pain, Banks and Kerns2 argued that ICPs with a psychological diathesis (eg, maladaptive cognitions) develop depression when they are confronted with stressors (eg, stressful relationships, nonvalidating medical responses). Although marital functioning is not the focus of their model, marital dysfunction and invalidating spouse responses can easily fit within the realm of stressful relationships.

In sum, several models identify marital functioning variables including marital satisfaction, spouse responses to pain, spousal support, and marital interaction as variables of importance in the chronic pain experience. We now turn to the empirical evidence to determine whether aspects of these models have received support.

Review of the Empirical Literature

To be included in this review, studies were required to have examined the relationship between marital functioning variables and at least one of the following aspects of the chronic pain experience: pain severity or intensity; physical disability, functional impairment, or activity level; pain behaviors; and psychosocial disability, depression, or other forms of psychological distress. These empirical studies were also required to speak specifically to chronic, rather than acute, pain conditions and to non-terminal pain conditions, which excluded studies on cancer pain. Marital functioning variables included marital satisfaction, spouse responses to pain, spousal support, and marital interaction. Although many other studies also examined social support more generally, a review of all types of support is beyond the scope of the present article. We therefore focus on support from one’s spouse (for a review on social support and cancer pain see Zaza and Baine103). We completed comprehensive searches by using the above search terms in Psychinfo, Science Direct, and Medline. We also reviewed the reference sections of relevant articles to ensure inclusion of articles not tapped by these databases. This comprehensive search resulted in a total of 74 studies that examined chronic pain, marital functioning, and psychological distress. These studies were published in peer-reviewed journals between 1978 and 2005.

To aid in the interpretation of findings, we developed a rating system by which we rated each article for study quality and strength or magnitude of the findings. Strength ratings were based on Cohen’s effect size guidelines for d, r, and f(ie, strong support = large effect; medium support = medium effect; weak/no support = small or no effect), regardless of statistical significance.21 Note that a minus sign (-) indicates a negative or inverse relationship between the variables in question, a plus sign (+) indicates a positive relationship, and an x indicates no effect. For strength ratings, there was 97% agreement between the raters, and consensus for disagreements was reached by means of discussion. Quality ratings (adequate = *, good = **, and superior = ***) were based on the psychometric properties of the measurement tools used, the sample size, use of control groups, and the extent to which authors used multivariate analyses. There was 86% agreement between raters on quality of the studies, and, in fact, all studies were deemed at least of “good” quality. Again, disagreements between raters were resolved through discussion. The results of these ratings are presented in tables that accompany each section below.

We organized the review of the empirical literature by examining the relationships of the pain and disability variables with the various marital functioning variables. One might argue that this organization implies that we are treating the pain and disability variables as dependent variables; however, most of the studies reviewed here are correlational. Therefore, it is likely that marital functioning variables can also be viewed as dependent variables, or that the relationships are bi-directional in nature.

Pain Severity

Self-reported pain severity is perhaps the most frequently measured pain experience variable. Likewise, marital satisfaction is a commonly measured general marital functioning variable in the chronic pain literature. As shown in Table 1, several studies have noted that pain severity was not directly related to marital satisfaction in several chronic pain samples of men and women.11,14,55 In contrast, 2 studies of ICPs found that pain severity was positively related to marital satisfaction such that less pain was related to lower satisfaction.30,46 Another study yielded a negative relationship between these variables.45 However, many other studies that assessed both variables did not report these correlations.25,58,64,69,71-73,77,85,86,96,100 Although it is unclear, it is likely that these researchers did not report the correlations because they were weak or not significant.

Table 1.

Pain Severity and Marital Functioning

| VARIABLE | STUDY | STRONG SUPPORT | MODERATE SUPPORT | WEAK/NO SUPPORT | STUDY QUALITY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital satisfaction | |||||

| Cano et al14(2004) | x | *** | |||

| Cano et al11(2000) | x | *** | |||

| Flor et al30(1989) | + | *** | |||

| Kerns et al46(1990) | + | *** | |||

| Kerns and Turk45(1984) | - | *** | |||

| Masheb et al55(2002) | x | *** | |||

| Spousal support | |||||

| Positive | Kerns and Turk45(1984) | x | *** | ||

| Revenson and Majerovitz64(1990) | + | *** | |||

| Riemsma et al65(2000) | - | *** | |||

| Schiaffino and Revenson83(1995) | x | ** | |||

| Waltz et al101(1998) | - | *** | |||

| Problematic | Revenson and Majerovitz64(1990) | + | *** | ||

| Riemsma et al65(2000) | + | *** | |||

| Schiaffino and Revenson83(1995) | + | ** | |||

| Waltz et al101(1998) | + | *** | |||

| Spouse responses | |||||

| Negative | Burns et al10(1996) | + | ** | ||

| Cano et al14(2004) | x | *** | |||

| Cano et al11(2000) | + | *** | |||

| Flor et al29(1987) | + | ** | |||

| Flor et al30(1989) | x | ** | |||

| Manne and Zautra52(1990) | + | ** | |||

| Schwartz et al87(1996) | + | ** | |||

| Turk et al96(1992) | x | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102(1997) | + | ** | |||

| Solicitous | Burns et al10(1996) | + | ** | ||

| Cano et al11(2000) | + | *** | |||

| Flor et al30(1989) | + | *** | |||

| Kerns et al46(1990) | + | *** | |||

| Lousberg et al50(1992) | + | ** | |||

| Turk et al96(1992) | + | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102(1997) | + | ** | |||

| Distracting | Cano et al11(2000) | + | *** | ||

| Flor et al30(1989) | + | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102(1997) | + | ** |

no effect

superior

good

Perceived spousal support is another marital variable that has been of particular interest to rheumatoid arthritis (RA) researchers. For instance, ICPs’ perceptions of problematic spousal support (ie, unhelpful advice, trying to change the patient) have also related positively with pain severity and elevated disease activity in RA.64,65,83,101 Likewise, positive support (ie, advice-giving, daily interaction) was associated with increased pain severity in one study.64 However, positive support was negatively associated with pain severity in 2 studies65,101, and in other studies, the 2 variables were not related.45,83

Researchers have also investigated the relationship between pain severity and pain-specific marital functioning as measured by the Multidimensional Pain Inventory (MPI) spouse responses to pain subscales. Researchers found that negative responses are positively related to pain severity in both community and clinic samples with chronic musculoskeletal pain ICPs10,11,29,52,87 and RA.102 In contrast, some studies of clinic samples yielded no association between negative spouse responses and pain severity.14,30,96

Several researchers have found that spouses’ perceptions of their own solicitous responses were positively related to pain intensity.10,30,46,50,96,102 Cano et al11 found that the relationship between pain severity and solicitious spouse responses on the MPI was significant for female, but not male, ICPs attending a pain clinic. Marital satisfaction might in fact moderate the relationship between spouse solicitousness and the pain experience. Flor et al30 found a significant and positive relationship between solicitous partner responses and pain severity for married men and unmarried women, but not married women unless they were maritally satisfied. Two other groups of researchers46,96 also found that solicitous spouse responses were positively related to pain severity in maritally satisfied, pain treatment-seeking ICPs. It is possible that solicitous spouse responses are more reinforcing when the quality of the relationship is good. Within the context of a poor relationship, ICPs might interpret solicitous spouse responses in a negative manner or as something spouses are obligated to do.

Findings concerning distracting responses have not been reported as frequently as those for negative and solicitous spouse responses. Williamson et al102 found that ICPs’ ratings of distraction were positively related to pain severity. Another study showed that distracting spouse responses were significantly and positively related to men’s but not women’s pain severity.11 Similar to the solicitous spouse response findings, marital satisfaction has been shown to moderate the relationship between distracting spouse responses and pain, such that distracting spouse responses are more strongly related to pain severity in maritally satisfied women.30 This relationship was not significant, however, for male ICPs. Some studies assessed other types of spouse responses to pain (ie, solicitous and negative); however, they did not assess for distracting spouse responses.10

Overall, a consistent positive relationship was demonstrated between solicitous and distracting spouse responses and pain severity. In addition, 6 of the 9 studies examining negative spouse responses reported a positive relationship with pain severity. These findings support cognitive-behavioral theories. There was also some evidence for a positive association between problematic support and pain severity. Contrary to some theoretical models (eg, Burman and Margolin9), there was little evidence for a relationship between pain severity and general marital functioning (ie, marital satisfaction, positive spousal support). However, marital satisfaction appeared to be an important contextual variable that influenced the relationship between pain-specific marital functioning (ie, spouse responses) and pain severity. Gender might also moderate the association between pain severity and marital functioning variables as seen in some studies.

Physical Disability and Activity Limitations

Another variable of interest in the chronic pain literature is physical disability, also referred to as activity limitation and interference in this review (Table 2). A study of ICPs attending a rehabilitation center found that spouses’ reports of ICPs’ disability were positively related to ICPs’ marital satisfaction.7 Similarly, marital satisfaction was positively related to marital satisfaction in women with chronic vulvar pain.55 In contrast, spouse’s reported marital satisfaction has been negatively related to disability in clinic samples.68,72,78 Gender might influence this relationship, because one study found that disability was negatively related to marital satisfaction in female but not in male ICPs.78 Although ICPs’ marital satisfaction and disability were assessed in other studies, the relationship between these 2 variables was not reported.30

Table 2.

Physical Disability/Activity Limitations and Marital Functioning

| VARIABLE | STUDY | STRONG SUPPORT | MODERATE SUPPORT | WEAK/NO SUPPORT | STUDY QUALITY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital satisfaction | |||||

| Block and Boyer7(1984) | + | ** | |||

| Masheb et al55(2002) | + | *** | |||

| Romano et al72(1997) | - | *** | |||

| Romano et al68(1989) | - | ** | |||

| Saarijarvi et al78(1990) | - | ** | |||

| Spousal support | |||||

| Positive | Goodenow et al36(1990) | x | *** | ||

| Patrick and D’Eon62(1996) | - | ** | |||

| Riemsma et al65(2000) | + | *** | |||

| Problematic | Riemsma et al65(2000) | + | *** | ||

| Spouse responses | |||||

| Negative | Cano et al14(2004) | + | *** | ||

| Flor et al29(1987) | - | ** | |||

| Flor et al30(1989) | x | *** | |||

| Manne and Zautra51(1989) | + | ** | |||

| Manne and Zautra52(1990) | + | ** | |||

| Schwartz et al87(1996) | + | ** | |||

| Turk et al96(1992) | x | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102(1997) | + | ** | |||

| Solicitous | Flor et al29(1987) | - | ** | ||

| Lousberg et al50(1992) | + | ** | |||

| Romano et al71(1995) | + | ** | |||

| Turk et al96(1992) | + | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102(1997) | + | ** | |||

| Distracting | Nicassio and Radojevic60(1993) | - | ** | ||

| Turk et al96(1992) | + | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102(1997) | + | ** |

no effect

good

superior

At least 3 separate studies examined the effect of positive support on disability and activity limitations. Both positive and problematic support from others, including spouses, was positively associated with disability in a sample of patients with RA.65 In another study, ICPs’ stationary bicycle output was predicted by their reported pain severity and perceptions of positive spousal support.62 Specifically, ICPs who perceived their spouses as particularly supportive were able to cycle longer than ICPs who did not perceive their spouses as supportive. Researchers have also found that high levels of family support were not related to physical disability in patients with RA.36 In that study, however, the sample consisted only of women, compared with mixed sex samples in the other studies.

Researchers have also studied pain-specific marital functioning in relation to disability. Many studies have found a positive relationship between negative spouse responses and functional impairment, reduced activity levels, and psychosocial impairment.14,51-53,87,102 However, negative spouse responses have also been associated with greater, not reduced, ICP activity in a pain clinic sample.29 This study used a diary method to assess spouse negative responses, whereas the other studies used only the MPI. Furthermore, these researchers used a sample of patients with heterogeneous pain conditions (ie, phantom limb, autoimmune diseases, and musculoskeletal pain), whereas the other studies were more focused on one condition (ie, low back pain, RA). Other studies of clinic samples failed to find an association between negative responses and disability.30,96

ICPs’ perceptions of solicitous spouse responses to pain have also been explored. Solicitous spouse responses as recorded in a diary have been related to reductions in activity limitation in a pain clinic sample.29 Another research team found that solicitous spouse responses were positively associated with pain interference.102 Lousberg et al50 found that ICPs’ perceptions of spouse solicitous responses were not related to walking time or exertion measured by heart rate; however, spouses’ reports of their solicitous responses were significantly and positively related to ICPs’ activity limitations. Researchers have found that marital satisfaction moderated the relationship between disability and solicitous spouse responses such that ICPs who are maritally satisfied exhibited a stronger relationship between solicitous spouse responses and disability than ICPs who are not as satisfied within their marriage.96 Observed solicitous spouse responses after patient displays of pain behaviors have also been reported to predict greater physical disability in more depressed ICPs.71 On the other hand, this research failed to link solicitous spouse responses to psychosocial disability, suggesting that although the partners’ solicitousness might contribute to physical debilitation, other factors or spouse behaviors might affect the psychosocial aspects of the pain experience.

Williamson et al102 found that ICPs’ ratings of distracting spouse responses were positively related to interference. Similarly, Turk et al96 also found that distracting spouse responses in the presence of marital satisfaction were positively related to disability in a sample from a pain clinic. On the other hand, Nicassio and Radojevic60 noted in their study that attempts by family members, the majority of whom were spouses, to engage ICPs in recreational activities were related to decreased disability in patients with RA and fibromyalgia.

The review of the research relating to disability revealed that there is an inconsistent relationship between marital satisfaction and spousal support and disability. As with pain severity, marital satisfaction might serve as a contextual variable that affects the degree to which pain-specific marital functioning and disability are related. Conversely, pain-specific marital functioning variables such as negative spouse responses to pain appear to be more consistently related to physical disability. These results support theories stressing the importance of ICPs’ interpretations of their pain experiences. In addition, greater attention to ICPs in the form of spouse responses suggests that reinforcement of pain behaviors might be related to disability. The discrepancies in the findings for the relationships between marital functioning and disability variables might be due, in part, to the diversity of instruments used to assess disability and activity limitations. As an example of 2 studies finding conflicting results, Romano et al71 used ICPs’ reports, whereas Block and Boyer7 used spouses’ reports. There was some evidence that gender might also have a moderating role in the relationship between solicitous responses and disability. Continued research on gender differences and multiple informants’ perceptions of support provision or spouse responses and disability might show that relationships between marital variables and disability depend on the reporter and the measure used.

Pain Behaviors

Of the pain variables, pain behaviors have not received as much attention from pain researchers interested in marital functioning, despite the importance placed on social reinforcement in operant theory. ICPs more frequently respond to laboratory-induced marital conflict, which is an indicator of marital dissatisfaction, by engaging in pain behaviors rather than active responses such as yelling or criticizing the partner.86 Similarly, other research groups have demonstrated a negative relationship between self-reported marital satisfaction and pain behaviors.72 However, other researchers have not found a relationship between marital satisfaction and the total number of pain behaviors in chronic pain samples such as RA and gynecologic pain.102

Pain-specific marital functioning has also been examined in relation to pain behaviors, which fits with operant theory. One study found that observed negative spouse responses lead to decreases in ICP nonverbal pain behavior more frequently in pain clinic ICPs than in control participants.70 Observational studies have also demonstrated that solicitous spouse behaviors predicted greater rates of pain behaviors in ICPs.63,70,71 Similarly, Turk et al96 noted a positive association between solicitous and distracting spouse responses with pain behaviors. Romano et al71 also demonstrated that observed solicitous spouse responses were associated with patient pain behaviors in patients reporting more pain.

The emerging evidence suggests that marital dissatisfaction is correlated negatively with pain behaviors (Table 3). Perhaps pain behavior functions as an escape from aversive interactions with one’s spouse. In contrast, solicitous spouse responses are positively related to pain behaviors, supporting operant models of pain. Sampling issues across studies might need to be considered. For instance, studies that found a relationship between pain behaviors and general marital satisfaction included samples of ICPs who suffered predominantly from low back pain,72,86 whereas the study that did not note such an association was conducted with other pain samples (ie, RA, gynecologic pain).102

Table 3.

Pain Behaviors and Marital Functioning

| VARIABLE | STUDY | STRONG SUPPORT | MODERATE SUPPORT | WEAK/NO SUPPORT | STUDY QUALITY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital satisfaction | |||||

| Romano et al72 (1997) | - | ** | |||

| Schwartz et al86 (1994) | - | *** | |||

| Williamson et al102 (1997) | x | ** | |||

| Spouse responses | |||||

| Negative | Romano et al70 (1992) | - | *** | ||

| Solicitous | Paulsen and Altmaier63 (1995) | + | *** | ||

| Romano et al70 (1992) | + | *** | |||

| Turk et al96 (1992) | + | *** | |||

| Romano et al71 (1995) | + | ** | |||

| Distracting | Turk et al96 (1992) | + | *** |

no effect

good

superior

Psychological Distress

As mentioned earlier, depression is highly comorbid with both chronic pain and marital difficulties. Several reviews of the literature and numerous empirical studies have already demonstrated the relationship between psychological distress, pain severity, disability, and pain behaviors2,9,11,14,46; therefore, our review of the empirical literature focuses on the link between marital functioning and psychological distress variables.

Many research groups have demonstrated a negative association between marital satisfaction and depressive symptoms in community and clinic samples of ICPs.11,14,46,72,78,85,100 Cano et al14 also showed that marital satisfaction was uniquely related to anxiety symptoms even when controlling for pain severity and disability in a clinic sample. In one case, depressive symptoms and marital satisfaction were not associated,25 and in many instances, the relationship between marital satisfaction and depressive symptomatology was not reported.39,60,69,73,85

The treatment literature also suggests a relationship between marital satisfaction and psychological distress. Saarijarvi et al79,81 conducted couples therapy with ICPs and found that the treatment group reported significant decreases in psychological symptoms, whereas the control group reported increases in symptoms. These studies do not appear in Table 4 because an effect size reflecting the relationship between changes in marital satisfaction and distress was not reported. Keefe et al42 also found that improvements in marital satisfaction during coping skills training related to better outcomes on psychological distress for ICPs whose spouse participated compared with ICPs whose spouse did not participate in the training. It appears that changes in marital satisfaction are indeed associated with changes in psychological distress.

Table 4.

Psychological Distress and Marital Functioning

| VARIABLE | STUDY | STRONG SUPPORT | MODERATE SUPPORT | WEAK/NO SUPPORT | STUDY QUALITY |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marital satisfaction | |||||

| Cano et al14 (2004) | - | *** | |||

| Cano et al11 (2000) | - | *** | |||

| Feinauer and Steele25 (1992) | x | ** | |||

| Keefe et al42 (1996) | - | *** | |||

| Kerns et al46 (1990) | - | *** | |||

| Mohamed et al58 (1978) | - | ||||

| Romano et al72 (1997) | - | *** | |||

| Saarijarvi et al78 (1990) | - | ** | |||

| Schwartz et al85 (1991) | - | *** | |||

| Walsch et al100 (1998) | - | ** | |||

| Spousal support | |||||

| Positive | Feldman et al26 (1999) | - | ** | ||

| Goodenow et al36 (1990) | - | *** | |||

| Revenson and Majerovitz64 (1990) | + | ** | |||

| Riemsma et al65 (2000) | - | *** | |||

| Schiaffino and Revenson83 (1995) | - | ** | |||

| Waltz et al101 | - | *** | |||

| Problematic | Revenson and Majerovitz64 (1990) | + | *** | ||

| Riemsma et al65 (2000) | + | *** | |||

| Schiaffino and Revenson83 (1995) | + | ** | |||

| Waltz et al101 (1998) | + | *** | |||

| Spouse responses | |||||

| Negative | Burns et al10 (1996) | + | ** | ||

| Cano et al14 (2004) | + | *** | |||

| Cano et al11 (2000) | + | *** | |||

| Kerns et al46 (1990) | + | *** | |||

| Manne and Zautra51 (1989) | + | ** | |||

| Turk et al96 (1992) | + | *** | |||

| Solicitous | Burns et al10 (1996) | + | ** | ||

| Cano et al11 (2000) | x | *** | |||

| Flor et al29 (1987) | + | ** | |||

| Distracting | Cano et al11 (2000) | x | *** | ||

| Kerns et al46 (1990) | + | *** | |||

| Combined | Goldberg et al35 (1993) | - | *** |

no effect

superior

good

Only 2 studies have examined the relationship between marital satisfaction and diagnoses of depression. Mohamed et al58 found that individuals diagnosed with depression who also had pain reported more marital discord and depressive symptoms than those with diagnoses of depression but no pain. Cano et al14 examined a group of married ICPs from a back pain clinic and found that those with a current diagnosis of depressive disorder (ie, major depression, dysthymia, or both) reported significantly more marital dissatisfaction than non-depressed ICPs. However, once pain variables such as pain severity and physical disability were entered, this relationship disappeared.

Other forms of marital functioning have been examined as a correlate of psychological distress, including spousal support. Revenson and Majerovitz64 found that positive spousal support provision, as reported by both ICP and spouses, was positively related to depressive symptoms in patients with RA. In contrast however, positive spousal support has more consistently associated with depressive symptoms in a negative manner in a similar sample of patients with RA.36 Similar findings were reported in several samples of ICPs with RA.65,83,101 Feldman et al26 found similar results in a community sample; however, these authors included support from others including parents, children, friends, or co-workers, although spouses were most often reported as providing support. Research also suggests that problematic support is associated with increased depressive symptoms.64,65,101 Schiaffino and Revenson83 found a similar positive relationship in research with a predominantly female sample.

In terms of pain-specific marital functioning, negative spouse responses were related to elevated depressive symptoms in numerous studies of clinic and community samples of ICPs.10,11,14,46,51,52,96 Marital satisfaction is an important moderator of the relationship between negative spouse responses and depressive symptoms. Turk et al96 found that negative spouse responses were positively related to depressive symptoms for ICPs who were maritally satisfied. In contrast, Kerns et al46 found that negative spouse responses in the context of a maritally discordant relationship were related to elevated depressive symptoms. The conflicting findings on marital satisfaction as a moderator of the relationship between negative spouse responses and depression might be due, in part, to relationship and pain duration. The mean years married in the studies by Kerns et al and Turk et al were 21 and 9 years, respectively. Likewise, pain duration was longer in the study by Kerns et al than in the study by Turk et al (10 years and 5.5 years, respectively). Couples change over time, leading to changes in the way spouse responses are perceived.15 Cano et al14 did not find support for these interactions in their study of clinic ICPs, perhaps because they also examined pain severity and physical disability as predictors of symptoms, whereas Kerns et al and Turk et al did not. Cano et al also found that negative spouse responses were uniquely associated with anxiety symptoms in ICPs from a clinic, even after controlling for the effects of pain severity and physical disability. Negative spouse responses were also related to depressive disorders; however, when pain severity and disability were accounted for, negative spouse responses were no longer related to depression diagnoses.

Two research groups found that solicitous responses were also positively related to depressive symptoms in clinic populations of ICPs.10,29 Although there are few researchers who report on distracting spouse responses in relation to depressive symptoms, at least one group has noted a positive relationship.46 Still others have not found any significant associations between solicitous spouse or distracting responses and depressive symptoms.11 Goldberg et al35 found that the effect of activity interference on depressive symptoms was buffered by a combined measure of solicitous, distracting, and negative spouse responses in a musculoskeletal pain sample. However, this result is difficult to interpret, given that few researchers have considered these different types of responses as a unitary construct.

In sum, the empirical evidence demonstrates a strong and consistent relationship between marital satisfaction and psychological distress in pain samples. However, the association between marital satisfaction and mood disorders is weak. Because few researchers have assessed diagnoses of mood disorders, additional research is needed before stronger conclusions can be made about more severe forms of distress. Negative spouse responses were the most studied and most consistently related pain-specific marital functioning correlate of psychological distress. The evidence on spousal support was mixed, most likely because there was great variation across studies in the measurement of spousal support.

Where Do We Go From Here?

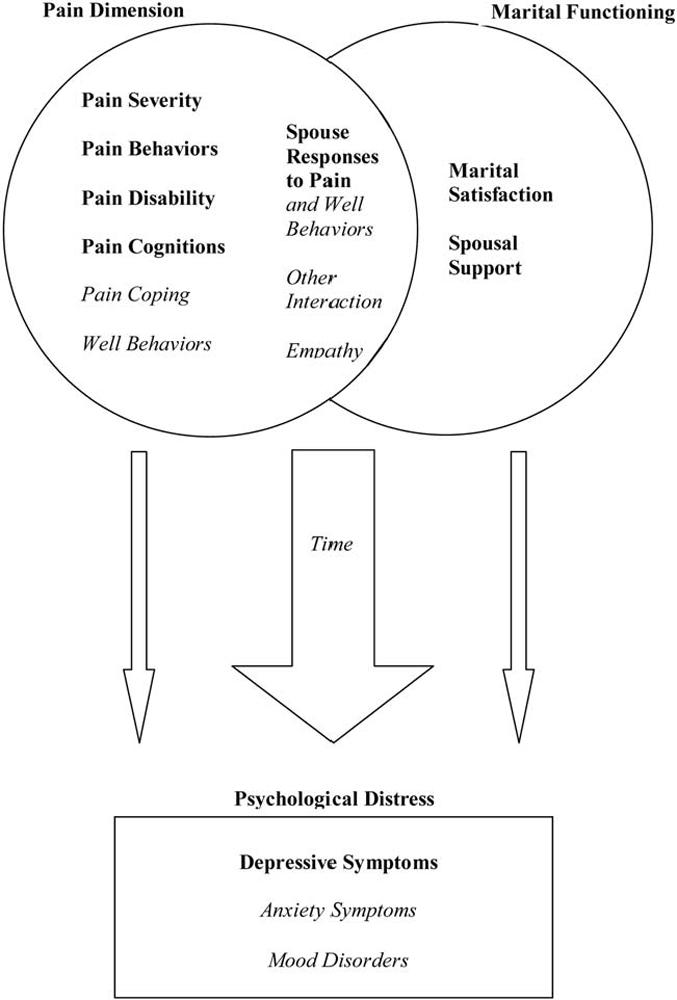

The empirical literature on couples and pain has demonstrated support for operant and cognitive-behavioral theories of the pain experience. There is little support for a link between marital satisfaction and perceived spousal support and pain variables. Rather, pain-specific aspects of marital functioning, spouse responses, are associated with pain outcomes. Marital satisfaction appears to have an indirect link with pain severity through the effect of these spouse responses. In addition, the research supported the theorized links between marital functioning variables and psychological distress and between pain, disability, and psychological distress. These demonstrated relationships might be viewed in bold type in Fig 1.

Figure 1.

Working model of the interrelationships between marital functioning, pain, and psychological distress. Variables printed in bold have been demonstrated in this review to have consistent relationships with other variables in the model. Variables printed in italics need further study before strong conclusions can be made.

However, important questions remain about the role of marital functioning in the chronic pain experience. In the pain literature, spouse responses to pain and marital satisfaction have been the most frequent marital variables of interest in relating to pain severity, disability, and pain behaviors. Yet research is needed on other dimensions of the pain experience that might be affected by these variables, such as pain acceptance.56 Research is also needed to determine whether other variables better explain the relationships between spouse responses, marital satisfaction, and pain variables. For instance, cognitive-behavioral theory would suggest that ICPs’ attributions for spouse responses to pain are most important. Perhaps these attributions are what were indirectly measured in the studies finding an interaction between spouse responses and marital satisfaction in predicting pain severity and depressive symptoms.27,96 Similarly operant models suggest that spouse responses can be significant reinforcers of well behaviors; however, the focus of the research has been on reinforcement of pain behaviors. The use of newer measures to assess reinforcement of well behaviors such as the Spouse Response Inventory88 is encouraged to test and expand theories of pain.

Moreover, marital functioning constitutes a broader range of constructs and measurable variables including marital interaction styles such as empathy, problem-solving, or argumentativeness, which are important variables of interest in the couples literature.6,41,75,84 Empathy is emerging as a particularly important variable that might have consequences for ICPs and their spouses.37 Understanding the process through which spouses develop empathy for each other might provide additional directions for more efficient treatments of pain and distress. Empathy might also account for why spouses often underestimate and overestimate pain and disability in ICPs.13,16,24,66 Issues discussed and avoided during interactions might be just as important. One study showed that although most patients with chronic pain verbally communicated with their families about pain, they found it inappropriate to talk about the pain unless asked.59

The investigation of interaction patterns could also address the problem associated with a continued focus on only the ICPs’ perceptions of the marriage and pain. Research has also shown that chronic pain affects spouses in a number of ways. Husbands of ICPs reported more loneliness, greater subjective stress, lower activity levels, and more fatigue than husbands married to women without pain.5 Spouses also reported a decline in marital satisfaction and sexual satisfaction after the onset of the pain condition,28,45,54 sometimes reporting more dissatisfaction than ICPs. Ahern et al1 noted that as ICPs become more socially isolated and psychosocially impaired as a result of pain, spouses might become less satisfied because they view the marital relationship as maladjusted.

Several factors might be important in evaluating the effect of pain on spouses. Several studies have found that ICP pain severity and disability were associated with spouse depression.1,5,32,74,100 Studies have also shown that spouses’ marital satisfaction is negatively associated with their own depressive symptoms,7,32,85 with one study demonstrating that this relationship was particularly strong for men.78 Evidence also demonstrated that spouses’ catastrophizing about their partners’ pain problems is related to their own depressive symptoms.17 Clearly, pain does not only affect the person with the pain problem, and researchers are encouraged to conduct more studies in which both members of the couple are assessed.

The inclusion of both members of the couple in studies of marriage and chronic pain is an improvement over one spouse’s participation; however, doing so might still not result in a couples approach to studying pain. For instance, the decision to use ICPs’ or spouses’ perceptions of the marriage or pain still results in an individual approach to studying couples’ processes. In addition, this approach creates a dilemma regarding whose perceptions are more accurate or meaningful when both are likely to contribute to the pain experience. Research that can speak to the dynamic interactions between couples by using couples’ self-reported experiences or, better yet, observational paradigms might provide more information about couples’ experiences and the strategies couples use to communicate about their pain and other issues in the marriage. Clearly, a broader definition of marital functioning and a couples-oriented approach to data collection are needed to determine the extent to which existing models can be supported and expanded.

As mentioned earlier, most of the studies on couples’ functioning and pain are cross-sectional. Therefore, the findings can also be interpreted from the perspective that pain, disability, and distress have a detrimental effect on couples’ relationships. It is likely that these variables are associated in a feedback loop. However, research is needed to address the temporal and causal associations among these variables. One way to pursue this goal is to conduct observational research as Romano et al70,71 have done to examine the sequential relationships between spouse responses and pain behaviors. Other methods include experimental designs with random assignment of couples to conditions to examine whether certain relational variables or processes are associated with pain outcomes. Yet another approach is to conduct longitudinal studies. Longitudinal research already suggests that living with chronic pain is more likely to result in depression than depression is to result in pain,8 and research in the couples field suggests that severe marital distress precedes depression,12 but researchers have not yet examined the extent to which marital functioning, pain, disability, and distress influence each other over time. Sophisticated statistical methods such as structural equation modeling and hierarchical linear modeling might also make special contributions to the literature by providing information about the dynamic interplay within the couple.

The mechanisms through which marital functioning relates to disability and psychological distress are poorly understood. Biologic variables such as immune response and hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal reactivity might play important roles in the interrelationships between marital distress and physical health.22,47 Understanding the mechanisms through which psychological distress is affected is also important, given that some have suggested that psychological distress, such as depressive symptoms, is qualitatively different from diagnoses of depression.82 For instance, depressive symptoms such as sadness and difficulty concentrating are normally distributed and might be indicators of diffuse distress, whereas symptoms of homeostatic disruption such as loss of interest and fatigue are specific to depression and markers of clinical illness.4 Consequently, different marital functioning variables might correlate with depressive symptoms as opposed to mood disorders; however, very little research has been conducted on the role of social influences in the mood disorders of ICPs. In addition, most studies have not examined other forms of psychological distress such as anxiety. Cohen and Rodriguez22 suggested that more research is needed to determine whether some types of psychological distress (eg, depression versus anxiety) are more strongly related to physical illness than others. As Clark and Watson20 noted, it can be difficult to disentangle the two from generic measures of psychological distress or even purported measures of depressive symptoms. We recommend that researchers continue to use measures designed to tease apart depressive from anxiety symptoms such as the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire (MASQ). Preliminary evidence suggests that this measure might be appropriate for use with community and clinic persons with musculoskeletal pain.33 At this point, strong conclusions can only be drawn regarding the relationship between couples’ variables and psychological distress in general.

A number of other methodologic issues must also be addressed in future research. Few studies used healthy control subjects,69,70 so there is a need for research that uses non-pain chronic illness control groups to determine the extent to which effects are specific to couples experiencing chronic pain. Multiple methodologies (eg, longitudinal, experimental, observational) and samples (eg, clinic vs community; back pain vs knee pain) will allow researchers to tease apart important differences that should be accounted for in models and treatment. The roles of various demographic variables (eg, age, race, ethnicity, sex) in the relationship between marital functioning and pain variables should also be explored. For instance, the likelihood of developing chronic pain conditions (eg, osteoarthritis) is greater with advancing age. Perhaps age of onset has a particular impact on marital quality as well as disability. Other personal characteristics might warrant further study in the area of marital functioning in pain including personality,39 hostility and anger expression,10 coping,61 and attachment.19,57 There is, undoubtedly, a great many directions this work could take.

Finally, continued testing and development of treatments that involve the spouse are necessary. Two treatment strategies have already begun to address pain in a couples context. Keefe et al42-44 tested a spouse-assisted coping skills treatment with ICPs suffering from osteoarthritis. Couples completed a 12-week program that teaches cognitive-behavioral skills to help manage pain. In the spouse-assisted treatment studies, emphasis is placed on educating the couple about the pain treatment and teaching the spouses appropriate responses to ICP pain expressions. Saarijarvi et al76,79-81 have addressed other marital issues including communication strategies and spousal support. Couples attended 5 monthly sessions with a therapist who used an approach that encouraged couples to explore their relationship. The therapist used reflective questioning to encourage couples to gain insight about their relationship dynamics. Although pain was not the direct focus of the therapy, each session began with a review of each spouse’s health, and couples could talk about any other relationship-centered topic, including pain, in the rest of the session. Both treatments resulted in improved functional status, marital satisfaction, and well-being for couples.

Other clinical approaches might also be beneficial on the basis of our review of the literature. For example, treatment programs might be more effective when explicit training is provided in the effective communication or development of empathy.18,40 In addition, cognitive aspects of chronic pain such as catastrophizing or acceptance might be addressed. Furthermore, match to treatment has not yet been investigated in couples approaches to chronic pain treatment. Some couples might benefit from spouse-assisted coping skills training, whereas others might benefit more from a traditional couples therapy approach. Other couples might see benefits with both treatments. For instance, happily married couples might benefit from spouse-assisted coping, whereas maritally dissatisfied couples might benefit from couples therapy or from both programs. For the many couples in which both spouses have pain,16 a different approach altogether might be beneficial.

Conclusion

In sum, several theoretical models suggest that marital functioning plays an important role in the pain experience for both ICPs and their spouses. Some support was found for these theories as shown in the tables and the working model in Fig 1, which depicts in bold only those relationships that have been supported in the empirical literature thus far. However, we identified several relationships that were not supported (ie, marital satisfaction and pain severity), as well as several that have not yet been investigated as indicated in italics in Fig 1. Although this review suggests that the couple’s relationship should be an important consideration in pain research and treatment, additional research is needed to fully understand the complex interplay of chronic pain and couples contextual variables. Clearly this is a field with a number of exciting research opportunities to pursue.

References

- 1.Ahern DK, Adams A, Follick MJ. Emotional and marital disturbance in spouses of chronic low back pain patients. Clin J Pain. 1985;1:69–74. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banks SM, Kerns RD. Explaining high rates of depression in chronic pain: A diathesis-stress framework. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:95–110. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beach SRH, Sandeen E, O’Leary KD. Depression in Marriage. Guilford; New York, NY: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beach SRH, Amir N. Is depression taxonic, dimensional, or both. J Abnorm Psychol. 2003;112:228–236. doi: 10.1037/0021-843x.112.2.228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bigatti SM, Cronan TA. An examination of the physical health, health care use, and psychological well-being of spouses of people with fibromyalgia syndrome. Health Psychol. 2002;21:157–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biglan A, Hops H, Sherman L, Friedman LS, Arthur J, Osteen V. Problem solving interactions of depressed women and their spouses. Behav Ther. 1985;16:431–451. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Block AR, Boyer SL. The spouse’s adjustment to chronic pain: Cognitive and emotional factors. Soc Sci Med. 1984;19:1313–1317. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(84)90018-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown GK. A causal analysis of chronic pain and depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:127–137. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.2.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burman B, Margolin G. Analysis of the association between marital relationships and health problems: An interactional perspective. Psychol Bull. 1992;112:39–63. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burns JW, Johnson BJ, Mahoney N, Devine J, Pawl R. Anger management style, hostility and spouse responses: Gender differences inpredictors of adjustment among chronic pain patients. Pain. 1996;64:445–453. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cano A, Weisberg JN, Gallagher RM. Marital satisfaction and pain severity mediate the association between negative spouse responses to pain and depressive symptoms in a chronic pain patient sample. Pain Med. 2000;1:35–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2000.99100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cano A, O’Leary K. Infidelity and separations precipitate major depressive episodes and symptoms of nonspecific depression and anxiety. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:774–781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cano A, Johansen AB, Geisser M. Spousal congruence on disability, pain, and spouse responses to pain. Pain. 2004;109:258–265. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cano A, Gillis M, Heinz W, Geisser M, Foran H. Marital functioning, chronic pain, and psychological distress. Pain. 2004;107:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cano A. Pain catastrophizing and social support in married individuals with chronic pain: The moderating role of pain duration. Pain. 2004;110:656–664. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cano A, Johansen AB, Franz A. Multilevel analysis of spousal congruence on pain, interference, and disability. Pain. 2005;118:369–379. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cano A, Leonard MT, Franz A. The significant other version of the Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS-S): Preliminary validation. Pain. 2005;119:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christensen A, Jacobson N, Babcock J. Integrative behavioral couple therapy. In: Jacobson N, Gurman A, editors. Clinical Handbook of Couple Therapy. Guil-ford Press; New York, NY: 1995. pp. 31–90. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ciechanowski P, Sullivan M, Jensen M, Romano J, Summers H. The relationship of attachment style to depression, catastrophizing and health care utilization in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2003;104:627–637. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(03)00120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clark L, Watson D. Tripartite model of anxiety and depression: Psychometric evidence and taxonomic implications. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:316–336. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.3.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Hillsdale, NJ: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cohen S, Rodriguez M. Pathways linking affective disturbances and physical disorders. Health Psychol. 1995;14:374–380. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.14.5.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coyne JC. Depression and the response of others. J Abnorm Psychol. 1976;85:186–193. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.85.2.186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cremeans-Smith JK, Stephens MAP, Franks MM, Martire LM, Druley JA, Wojno WC. Spouses’ and physicians’ perceptions of pain severity in older women with osteoarthritis: Dyadic agreement and patients’ well-being. Pain. 2003;106:27–34. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(03)00268-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feinauer LL, Steele WR. Caretaker marriages: The impact of chronic pain syndrome on marital adjustment. Am J Family Ther. 1992;20:218–226. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Feldman S, Downey G, Schaffer-Neitz R. Pain, negative mood, and perceived support in chronic pain patients: A daily diary study of people with reflex sympathetic dystrophy syndrome. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:776–785. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Flor H, Turk DC, Rudy TE. Pain and families: II. Assessment and treatment. Pain. 1987;30:29–45. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(87)90081-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Flor H, Turk DC, Scholz OB. Impact of chronic pain on the spouse: Marital, emotional and physical consequences. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31:63–71. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90099-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Flor H, Kerns RD, Turk DC. The role of spouse reinforcement, perceived pain, and activity levels of chronic pain patients. J Psychosom Res. 1987;31:251–259. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(87)90082-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flor H, Turk DC, Rudy TE. Relationship of pain impact and significant other reinforcement of pain behaviors: The mediating role of gender, marital status and marital satisfaction. Pain. 1989;38:45–50. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90071-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fordyce WE. Behavioral Methods for Chronic Pain and Illness. Mosby; St. Louis, MO: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Geisser M, Cano A, Leonard M. Factors associated with marital satisfaction and mood among spouses of persons with chronic back pain. J Pain. 2005;6:518–525. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2005.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geisser M, Cano A, Foran H. Psychometric properties of the Mood and Anxiety Symptom Questionnaire in chronic pain patients. Clin J Pain. 2006;22:1–9. doi: 10.1097/01.ajp.0000146180.55778.4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisser ME, Robinson M, Keefe F, Weiner M. Catastrophizing depression and the sensory, affective and evaluative aspects of chronic pain. Pain. 1994;59:79–83. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)90050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg G, Kerns RD, Rosenberg R. Pain-relevant support as a buffer from depression among chronic pain patients low in instrumental activity. Clin J Pain. 1993;9:34–40. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199303000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Goodenow C, Reisine S, Grady K. Quality of social support and associated social and psychological functioning in women with rheumatoid arthritis. Health Psychol. 1990;9:266–284. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.9.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goubert L, Craig K, Vervoort T, Morley S, Sullivan M, Williams A, Cano A, Crombez G. Facing others in pain: The effects of empathy. Pain. 2005;118:285–288. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2005.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammen C. Generation of stress in the course of unipolar depression. J Abnorm Psychol. 1991;100:555–561. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.100.4.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hewitt PL, Flett GL, Mikail SF. Perfectionism and relationship adjustment in pain patients and their spouses. J Fam Psychol. 1995;9:335–347. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jacobson N, Christensen A, Prince S, Cordova J, Eldridge K. Integrative behavioral couple therapy: An acceptancebased, promising new treatment for couple discord. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:351–355. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.2.351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson SL, Jacob T. Marital interactions of depressed men and women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:15–23. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.1.15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, Salley A. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of osteoarthritic knee pain. Arthritis Care Res. 1996;9:279–291. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199608)9:4<279::aid-anr1790090413>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Keefe FJ, Caldwell DS, Baucom D, Salley A, Robinson E, Timmons K, Beaupre P, Weisberg J, Helms M. Spouse-assisted coping skills training in the management of knee pain in osteoarthritis: Long-term followup results. Arthritis Care Res. 1999;12:101–111. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(199904)12:2<101::aid-art5>3.0.co;2-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keefe FJ, Blumenthal J, Baucom D, Affleck G, Waugh R, Caldwell DS, Beaupre P, Kashikar-Zuck S, Wright K, Egert J, Lefebvre J. Effects of spouse-assisted coping skills training and exercise training in patients with osteoarthritic knee pain: A randomized controlled study. Pain. 2004;110:539–549. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kerns RD, Turk DC. Depression and chronic pain: The mediating role of the spouse. J Marriage Family. 1984;46:845–852. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kerns RD, Haythornthwaite J, Southwick S, Giller EL. The role of marital interaction in chronic pain and depressive symptom severity. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34:401–408. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90063-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kiecolt-Glaser J, Newton T. Marriage and health: His and hers. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:472–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Springer; New York, NY: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lipsey M, Wilson D. Practical Meta-Analysis. Sage Publications; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lousberg R, Schmidt AJM, Groenman NH. The relationship between spouse solicitousness and pain behavior: Searching of more experimental evidence. Pain. 1992;51:75–79. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90011-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Manne SL, Zautra AJ. Spouse criticism and support: Their association with coping and psychological adjustment among women with rheumatoid arthritis. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989;56:608–617. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.56.4.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Manne SL, Zautra AJ. Couples coping with chronic illness: Women with rheumatoid arthritis and their healthy husbands. J Behav Med. 1990;13:327–342. doi: 10.1007/BF00844882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Manne SL, Alfieri T, Taylor KL, Dougherty J. Spousal negative responses to cancer patients: The role of social restriction, spouse mood, and relationship satisfaction. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:352–361. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.3.352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Maruta T, Osborne D, Swanson DW, Halling JM. Chronic pain patients and spouses marital and sexual adjustment. Mayo Clin Proc. 1981;56:307–310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Masheb RM, Brondolo E, Kerns RD. A multidimensional, case-control study of women with self-identified chronic vulvar pain. Pain Med. 2002;3:253–259. doi: 10.1046/j.1526-4637.2002.02032.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McCracken LM. Social context and acceptance of chronic pain: The role of solicitous and punishing responses. Pain. 2005;113:155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.McWilliams LA, Cox BJ, Enns MW. Impact of adult attachment styles on pain and disability associated with arthritis in a nationally representative sample. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:306–364. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200012000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mohamed SN, Weisz GM, E.M. W The relationship of chronic pain to depression, marital adjustment, and family dynamics. Pain. 1978;5:285–292. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(78)90015-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Morley S, Doyle K, Beese A. Talking to other about pain: Suffering in silence. In: Devor M, Rowbotham MC, Wiesenfeld-Hallin Z, editors. Progress in Pain Research & Management. IASP Press; Seattle, WA: 2000. pp. 1123–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Nicassio PM, Radojevic V. Models of family functioning and their contribution to patient outcomes in chronic pain. Motivation Emotion. 1993;17:295–316. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nielson WR, Jensen MP. Relationship between changes in coping and treatment outcome in patients with fibromyalgia syndrome. Pain. 2004;109:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Patrick L, D’Eon J. Social support and functional status in chronic pain patients. Can J Rehabil. 1996;9:195–201. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Paulsen JS, Altmaier EM. The effects of perceived versus enacted social support on the discriminative cue function of spouses for pain behaviors. Pain. 1995;60:103–110. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00096-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Revenson T, Majerovitz S. Spouses’ support provision to chronically ill patients. J Soc Pers Relationships. 1990;7:575–586. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Riemsma R, Taal E, Wiegman O, Rasker JJ, Bruyn GAW, van Paassen HC. Problematic and postive support in relation to depression in people with rheumatoid arthritis. J Health Psychol. 2000;5:221–230. doi: 10.1177/135910530000500212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Riemsma RP, Taal E, Rasker JJ. Perceptions about perceived functional disabilities and pain of people with rheumatoid arthritis: Differences between patients and their spouses and correlates of well-being. Arthritis Care Res. 2000;13:255–261. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200010)13:5<255::aid-anr3>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Romano JM, Turner JA. Chronic pain and depression: Does the evidence support a relationship. Psychol Bull. 1985;97:18–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romano JM, Turner JA, Clancy SL. Sex differences in the relationship of pain patient dysfunction to spouse adjustment. Pain. 1989;39:289–295. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(89)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Romano JM, Turner JA, Friedman LS, Bulcroft RA, Jensen MP, Hops H. Observational assessment of chronic pain patient-spouse behavioral interactions. Behav Ther. 1991;22:549–567. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Romano JM, Turner JA, Friedman LS, Bulcroft RA, Jensen MP, Hops H, Wright SF. Sequential analysis of chronic pain behaviors and spouse responses. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1992;60:777–782. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.60.5.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Romano JM, Turner JA, Friedman JA, Bulcroft LS, Jensen RA, Wright SF. Chronic pain patient-spouse behavioral interactions predict patient disability. Pain. 1995;63:353–360. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00062-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Romano JM, Turner JA, Jensen MP. The family environment in chronic pain patients: Comparison to controls and relationship to patient functioning. J Clin Psychol Medical Settings. 1997;4:383–395. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Romano JM, Jensen MP, Turner JA, Good AB, Hops H. Chronic pain patient-partner interactions: Further support for a behavioral model of chronic pain. Behav Ther. 2000;31:415–440. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rowat KM, Knafl KA. Living with chronic pain: The spouse’s perspective. Pain. 1985;23:259–271. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(85)90104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ruscher SM, Gotlib IH. Marital interaction patterns of couples with and without a depressed partner. Behav Ther. 1988;19:455–470. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Saarijarvi S, Lahti T, Lahti I. Time-limited structural couple therapy with chronic low back pain patients. Family Systems Med. 1989;7:328–338. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Saarijarvi S, Hyyppa V, Lehtinen V, Alanen E. Chronic low back pain patient and spouse. J Psychosom Res. 1990;34:117–122. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(90)90015-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Saarijarvi S, Rytokoski U, Karppi S. Marital satisfaction and distress in chronic low-back pain patients and their spouses. Clin J Pain. 1990;6:148–152. doi: 10.1097/00002508-199006000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Saarijarvi S. A controlled study of couple therapy in chronic low back pain patients: Effects on marital satisfaction, psychological distress and health attitudes. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35:265–272. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90080-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Saarijarvi S, Rytokoski U, Alanen E. A controlled study of couple therapy in chronic low back pain patients: No improvement of disability. J Psychosom Res. 1991;35:671–677. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(91)90117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Saarijarvi S, Alanen E, Rytokoski U, Hyyppa M. Couple therapy improves mental well-being in chronic low back pain patients. A controlled, five year follow up study. J Psychosom Res. 1992;36:651–656. doi: 10.1016/0022-3999(92)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Santor DA, Coyne JC. Shortening the ces-d to improve its ability to detect cases of depression. Psychol Assess. 1997;9:233–243. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Schiaffino KM, Revenson TA. Relative contributions of spousal support and illness appraisals to depressed mood in arthritis patients. Arthritis Care Res. 1995;8:80–87. doi: 10.1002/art.1790080205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schmaling KB, Whisman MA, Fruzzetti AE, Truax P. Identifying areas of marital conflict: Interactional behaviors associated with depression. J Fam Psychol. 1991;5:145–157. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Schwartz L, Slater MA, Birchler GR, Atkinson JH. Depression in spouses of chronic pain patients: The role of patient pain and anger, and marital satisfaction. Pain. 1991;44:61–67. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(91)90148-Q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Schwartz L, Slater MA, Birchler GR. Interpersonal stress and pain behaviors in patients with chronic pain. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1994;62:861–864. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.4.861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schwartz L, Slater MA, Birchler GR. The role of pain behaviors in the modulation of marital conflict in chronic pain couples. Pain. 1996;65:227–233. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(95)00211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Schwartz L, Jensen MP, Romano JM. The development and psychometric evaluation of an instrument to assess spouse responses to pain and well behavior in patients with chronic pain: The Spouse Response Inventory. J Pain. 2005;6:243–252. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2004.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Severeijns R, Vlaeyen JWS, van den Hout MA. Do we need a communal coping model of pain catastrophizing? An alternative explanation. Pain. 2004;111:226–229. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2004.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sullivan M, Deon J. Relation between catastrophizing and depression in chronic pain patients. J Abnorm Psychol. 1990;99:260–263. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.99.3.260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Sullivan MJL, Stanish W, Waite H, Sullivan M, Tripp DA. Catastrophizing, pain and disablity in patients with soft-tissue injuries. Pain. 1998;77:253–260. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(98)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Sullivan MJL, Tripp DA, Santor D. Gender differences in pain and pain behavior: The role of catastrophizing. Cogn Ther Res. 2000;24:121–134. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sullivan MJL, Thorn B, Haythornthwaite JA, Keefe F, Martin M, Bradley LA, Lefebvre JC. Theoretical perspectives on the relation between catastrophizing and pain. Clin J Pain. 2001:1752–64. doi: 10.1097/00002508-200103000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Turk DC, Meichenbaum D, Genest M. Pain and Behavioral Medicine: A Cognitive-Behavioral Perspective. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 95.Turk DC, Kerns RD. The family in health and illness. In: Turk DC, Kerns RD, editors. Health, Illness and Families: A Life Span Perspective. Wiley; New York, NY: 1985. pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- 96.Turk DC, Kerns RD, Rosenberg R. Effects of marital interaction on chronic pain and disability: Examining the down side of social support—Special issue: Family and disability research: New directions in theory, assessment and intervention. Rehabil Psychol. 1992;37:259–274. [Google Scholar]

- 97.Turner JA, Jensen MP, Romano JM. Do beliefs, coping, and catastrophizing independently predict functioning in patients with chronic pain. Pain. 2000;85:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(99)00259-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Turner JA, Jensen MP, Warms CA, Cardenas DD. Catastrophizing is associated with pain intensity, psychological distress, and pain-related disability among individuals with chronic pain after spinal cord injury. Pain. 2002;98:127–134. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3959(02)00045-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Vlaeyen JWS, Kole-Snijders AMJ, Boeren RG, van Eek H. Fear of movement/(re)injury in chronic low back pain and its relation to behavioral performance. Pain. 1995;62:363–372. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00279-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Walsh JD, Blanchard EB, Kremer JM, Blanchard CG. The psychosocial effects of rheumatoid arthritis on the patient and the well partner. Behav Res Ther. 1998;37:259–271. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(98)00128-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Waltz M, Kriegel W, van’t Pad Bosch P. The social environment and health rheumatoid arthritis: Marital quality predicts individual variability in pain severity. Arthritis Care Res. 1998;11:356–374. doi: 10.1002/art.1790110507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Williamson D, Robinson ME, Melamed B. Pain behavior, spouse responsiveness, and marital satisfaction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Behav Modif. 1997;21:97–118. doi: 10.1177/01454455970211006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zaza C, Baine N. Cancer pain and psychosocial factors: A critical review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2002;24:526–542. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(02)00497-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]