Abstract

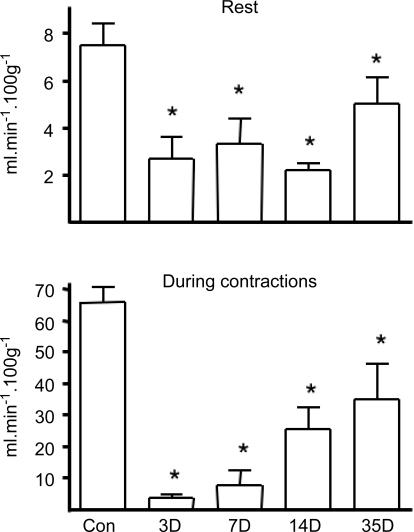

Impaired blood flow is thought to induce a pro-angiogenic environment due to local hypoxia, yet prolonged mild ischaemia induces only modest capillary growth. We compared the expression of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) mRNA and protein with capillary to fibre ratio (C: F) and muscle blood flow in extensor digitorum longus of rats that had undergone unilateral ligation of the common iliac artery. Resting blood flow during the first two weeks after ligation (3, 7 and 14 days) was decreased by ∼60% but recovered partially after 5 weeks (36% reduction). Functional hyperaemia (9-fold increase in blood flow during contractions) was eliminated in the first week after ligation, with a moderate recovery seen after 14 and 35 days. Muscle histology confirmed the absence of tissue necrosis or inflammation. Both VEGF mRNA (60%, P < 0.05) and protein levels (700%, P < 0.01) increased during the initial phase of ischaemia (at 1 and 3 days), well before any overt angiogenesis, and both declined towards control levels by 7 days. A secondary increase in VEGF protein (by 60% at 14 days, P < 0.05) preceded the 20% increase in C: F seen after 5 weeks, but occurred while VEGF transcript levels continued to decline (to 50% of control at 35 days, P < 0.05). Thus, evaluation of neither VEGF mRNA nor protein is an adequate index of angiogenic potential in response to ischaemia. We conclude that VEGF alone is insufficient to induce angiogenesis in ischaemic conditions, and that effective angiotherapy requires intervention aimed at other cytokines.

Following occlusion of major blood vessels, compensatory tissue neovascularization is an important adaptive response to overcome perturbation of oxygen homeostasis. Vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) is a key mediator of such ischaemia-induced angiogenesis (Ferrara, 2004), and it is important to understand how its production is regulated in ischaemic settings in order to advance the development of successful clinical angiogenic therapies. Patients with critical limb ischaemia display raised circulating levels of VEGF (McLaren et al. 2002), and higher than normal levels of VEGF mRNA (Tuomisto et al. 2004) and protein (Rissanen et al. 2002) in ischaemic leg muscles, but this condition involves pronounced muscle necrosis and inflammation. Similarly, in animal models of limb ischaemia where arterial ligation and/or excision lead to ischaemic muscle damage, necrosis, degeneration and regeneration, there is significant upregulation of VEGF mRNA and protein associated with capillary growth (Couffinhal et al. 1998; Rissanen et al. 2002; Luo et al. 2002). The histological presence of cellular infiltration and macrophages confirms this as an inflammatory type of angiogenesis. By contrast, patients with mild-to-moderate peripheral arterial disease of long-standing show little if any increase in muscle capillarity (Askew et al. 2005) or immunostaining for VEGF (Baum et al. 2005), despite persistent impairment in blood flow (Tang et al. 2005). This condition can be closely represented by unilateral ligation of the common iliac artery in the rat, which preserves adequate blood flow at rest and does not lead to either inflammation or muscle necrosis (Hudlicka et al. 1994) yet results in limited late-onset capillary growth in hindlimb muscles (Brown et al. 2003; Milkiewicz et al. 2003), similar to that described in the leg muscles in patients with intermittent claudication (Clyne et al. 1982).

The reported time course of VEGF upregulation in ischaemic muscle tissue is ambiguous. In rat and dog hearts, VEGF mRNA was rapidly induced by acute ischaemia, but no change was observed after 21 days (Matsunaga et al. 2000). During severe ischaemia and inflammation in hindlimb muscles, mRNA increased over 1 week and subsequently waned in mice and rabbits (Couffinhal et al. 1998; Rissanen et al. 2002), whereas Lloyd et al. (2003) reported no change in rats for 25 days after femoral artery ligation in the absence of muscle necrosis. VEGF protein was also reported to increase in skeletal muscle within days after induction of severe ischaemia, but not after longer periods (Couffinhal et al. 1998; Silvestre et al. 2001), although there appears to be a discrepancy between changes in VEGF mRNA expression and tissue level of VEGF protein, which is the relevant ligand for the receptor tyrosine kinases that orchestrate an angiogenic response. In addition, increased VEGF expression (mRNA) and/or production (protein) during muscle ischaemia may (Couffinhal et al. 1998) or may not (Cherwek et al. 2000) precede the appearance of new capillaries, depending on whether the severity of ischaemia leads to ischaemic damage and inflammation.

Since the time course of delayed angiogenesis has been clearly defined in our iliac artery ligation model of mild-to-moderate non-inflammatory ischaemia, we wished to establish the relationship between the transcriptional and post-transcriptional control of VEGF production by assessing VEGF mRNA and protein levels in acute (1 and 3 days) and chronically (7–35 days) ischaemic muscles. We related these changes to muscle blood flow as an index of potential muscle oxygen delivery.

Methods

Animals and surgical procedure

Experiments were performed on male Sprague-Dawley rats, 270–320 g body mass on the day of sampling. All surgical procedures were performed under aseptic conditions and halothane anaesthesia (2% Fluothane in 100% O2) in accordance with the United Kingdom Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act of 1986, inducing a transient (<5%) loss of body mass. Five groups of rats, assigned randomly, had blood flow limited by unilateral ligation of the right common iliac artery performed about 0.5 cm below the aortic bifurcation, and these were studied 1 (n = 4), 3 (n = 3), 7 (n = 6), 14 (n = 9) or 35 days (n = 9) later. A topical antibiotic (Duplocillin LA, NVS) and systemic analgesic (2.5 ml kg−1 buprenophine, s.c., Temgesic, NVS) were administered peri-operatively. Recovery from surgery was scored twice daily by trained animal technicians, to assess the severity of pain and leg usage. Analgesia was given to most animals for the first 48 h, i.e. until normal activity was resumed. Animals were weighed twice weekly as an additional check on level of discomfort. Seven animals without any intervention served as controls, previous data showing no difference between untreated and sham-operated controls (Hudlicka et al. 1994). At the end of each experiment, rats were anaesthetized and the right extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles were removed, weighed and frozen in liquid nitrogen, with samples for histochemistry frozen in cooled isopentane. Animals were then killed by pentobarbitone overdose (i.p.).

Northern analysis

Total RNA was isolated with TRIZOL Reagent (GibcoBRL, UK) according to the manufacturer's protocol, and had a ratio of absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm (A260/A280) between 1.75 and 1.9, depending on the sample. Total RNA (15 μg) was fractionated on a 1.0% agarose gel and transferred onto nylon-based membranes (Hybond-N+, Amersham, UK) by the capillary blot procedure, and integrity checked by staining with SYBR Green. Probes (50 ng) for VEGF and β-actin (kindly provided by Dr M. Zatyka, University of Birmingham, UK) were labelled with α-[32P] by randomly primed DNA synthesis (Boehringer Mannheim, UK). After purification of unincorporated nucleotides using G-50 Quick Spin Columns (Boehringer Mannheim, UK) the blots were hybridized at 68°C overnight in PerfectHyb hybridization buffer (Sigma, UK). Autoradiography was carried out with Phosphor screens (Kodak, UK), and relative quantification of the respective mRNAs was analysed using DOC 2000 and FX software (Bio-Rad, UK).

Western analysis

Frozen EDL muscles were finely ground over dry ice and homogenized in RIPA buffer with a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Mini Complete; Roche). Fifty grams of protein was fractionated on 12% SDS-PAGE, transferred to a PVDF membrane and blocked with 5% non-fat milk. Total cellular protein quality was always checked after electrophoresis by Ponceau S staining. The blots were exposed to rabbit polyclonal antibody against VEGF or mouse monoclonal antibody to actin (Santa Cruz, USA). Antibodies were detected with the enhanced chemiluminescence detective system (ECL; Amersham, UK) and the membranes were exposed to autoradiographic film (Kodak Biomax, Sigma, UK). Finally, images were scanned and densities of bands were quantified using Quantity One software (Bio-Rad, UK).

Capillary staining

To depict the anatomical capillary supply, frozen sections were stained for endothelial alkaline phosphatase (ALP) using SIGMA FAST 5-bromo-4chloro-3indolyl phosphatase (BCIP)/nitro blue tetrazolium (NBT)-buffered substrate tablets (Sigma, UK), as previously described (Milkiewicz et al. 2003). The extent of angiogenesis in the muscle was evaluated as the numerical capillary to fibre ratio (C: F) to control for any changes in muscle fibre size after the ischaemic insult.

Muscle blood flow and fatigue

Muscle blood flow was measured in separate groups of animals at 3, 7, 14 and 35 days after iliac artery ligation (n = 10, 10, 7 and 7, respectively) compared with 14 muscles from control animals, using the radiolabelled microsphere method (Hudlicka et al. 1994). Briefly, 15 μm microspheres labelled either with 46Sc or 113Sn (Du Pont NEN, Mechelen, Belgium) were injected into the left ventricle using a cannula advanced through the right carotid artery, at rest and at the end of a 5 min period of muscle contractions at 4 Hz under penthobarbital anaesthesia (50 mg kg−1i.p.). The reference sample was taken from one brachial artery using a precision infusion/withdrawal pump (Braun, Melsungen, Germany), while the other brachial artery was used to measure blood pressure. To measure muscle fatigue, the feet were clamped and the EDL and tibialis anterior tendons were attached to a strain gauge to record tension in response to stimulation of the peroneal nerve by means of bipolar silver electrodes (continuous stimulation at 10 Hz and 0.3 ms pulse width, and intensity sufficient to eleicit maximal contractions of up to 6 V). The fatigue index was calculated as the ratio of tension developed at the end of 5 min contractions to peak tension (Hudlicka et al. 1994).

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. Comparison between groups at a given time point was performed using ANOVA with Fisher's PLSD post hoc test.

Results

VEGF mRNA and protein expression

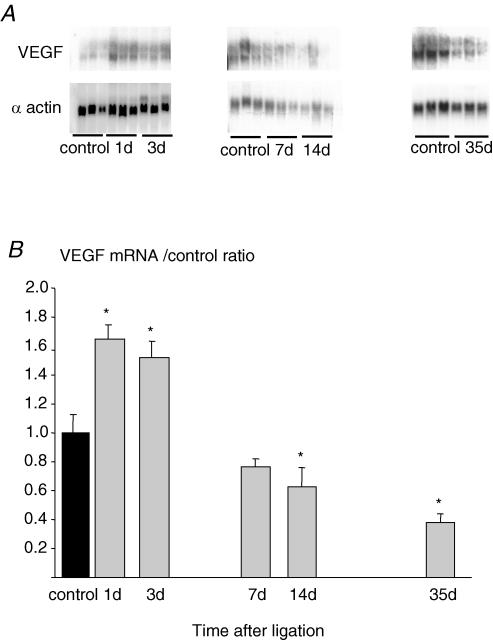

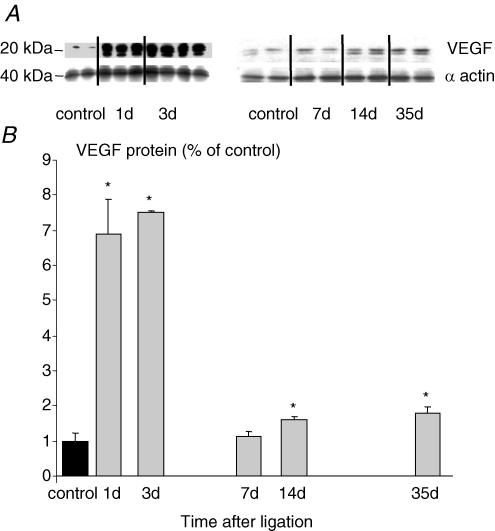

Ischaemia induced by iliac artery ligation led to a rapid and transient increase in VEGF mRNA in EDL muscles. After 1 and 3 days, the level of VEGF mRNA was elevated by ∼65%. Subsequently, there was a progressive reduction towards control levels at 7 days (1.0 ± 0.1 relative to control muscle values, n.s.), a significant decrease after 14 days (0.63 ± 0.1; P < 0.05) and a 50% decrease after 35 days (0.49 ± 0.06; P < 0.05, Fig. 1). Over the same time course VEGF protein concentration was elevated with a bimodal pattern. The first peak, a 7-fold increase, was detected after 1 and 3 days, but levels were normal after 7 days. A second, much smaller rise was apparent after 14 days (60%; P < 0.05 versus control) and 35 days (80%; P < 0.05 versus control; Fig. 2).

Figure 1. Effect of arterial ligation on VEGF expression by Northern analysis in ischaemic and non-ischaemic rat EDL versusβ-actin internal control for various times post-surgery (A), and quantification of VEGF expression normalized against non-ischaemic muscles (B).

Each bar represents mean ±s.e.m. (n = 6), *P < 0.05 versus control.

Figure 2. Effect of arterial ligation on VEGF protein levels by Western analysis in ischaemic and non-ischaemic rat EDL versusβ-actin internal control for various times post-surgery (A), and quantification of VEGF levels normalized against non-ischaemic muscles (B).

Each bar represents mean ±s.e.m. (n = 6), *P < 0.05 versus control.

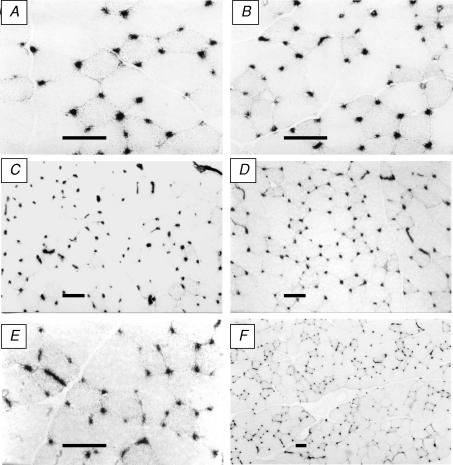

Muscle histology

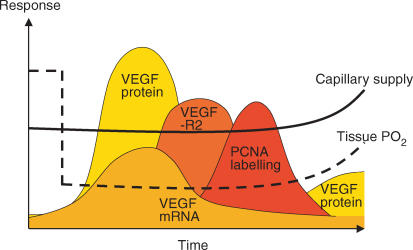

After ligation, EDL muscles showed no necrosis or gross cellular inflammation at any time point (Fig. 3). The ratio of muscle to body mass in control muscles (EDL/BM) was 0.49 ± 0.01, with no change 1 or 3 days after ligation. A small, but significant atrophy was observed 7 and 14 days after ligation (0.44 ± 0.01 at both intervals, P < 0.05 versus control), but by 35 days EDL/BM returned to control values (0.48 ± 0.01). Capillary: fibre ratio was not different from control values (1.41 ± 0.04) until 35 days after ligation, when there was a modest increase to 1.70 ± 0.10 (P < 0.05 versus control; Milkiewicz et al. 2003), and this late onset angiogenesis was confirmed previously by capillary proliferation studies which showed an increased number of capillaries labelled for PCNA (proliferating cell nuclear antigen) prior to the increase in C: F ratio (Brown et al. 2003; Milkiewicz et al. 2003). The temporal relationship between these changes and the changes in VEGF are shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 3. Representative cryosections of EDL muscles stained for alkaline phosphatase and showing maintenance of tissue integrity.

A and B, control, ligated 1 week, C and D, control, ligated 2 weeks; E and F, both ligated 5 weeks (scale bars = 50 μm).

Figure 4. A comparison of the time course of changes in VEGF mRNA and protein levels with that of VEGF-R2 levels and cell proliferation associated with capillaries.

The schematic illustrates the essentially simultaneous increase in VEGF expression and production, subsequent increases in angiogenic receptor expression and proliferative angiogenesis, and finally the coincidence of increased capillarity with a second wave of VEGF protein and improved tissue oxygenation.

Muscle blood flow and fatigue

Three days post-ligation, muscle blood flow at rest had decreased to 30–40% of the value in controls (7.5 ± 0.9 ml min−1 (100 g)−1). It remained at this low level for the first 14 days after surgery and, although higher in muscles after 35 days, was still significantly lower than in controls (P < 0.05; Fig. 5). In control muscles, flow increased about 9-fold during contractions, but there was no increase in muscle blood flow at 3 or 7 days post-ligation, and only a partial recovery after 14 and 35 days (P < 0.05 versus control; Fig. 5). The tension developed at the end of 5 min isometric contractions in control muscles represented 63.7 ± 2.2% of the peak tension. Muscles fatigued considerably more than controls after ligation, and showed a progressive recovery (17.1 ± 4.1%, 26.3 ± 13.8% and 35.2 ± 4.5% at 3, 7 and 14 days after ligation, respectively, all P < 0.05 versus control) with values not significantly different from controls (52.3 ± 4.3% versus 63.7 ± 2.2% in controls) 35 days after ligation.

Figure 5. Blood flow in tibialis anterior and extensor digitorum longus (combined samples) in control muscles (n = 14), and 3 (n = 10), 7 (n = 10), 14 (n = 7) and 35 days (n = 7) after ligation, at rest and at the end of 5 min isometric contractions at 4 Hz.

*P < 0.05 versus control.

Discussion

The current study has shown for the first time that during prolonged skeletal muscle ischaemia, VEGF mRNA and protein are differentially modulated in relation to angiogenesis. The basal (control) levels of VEGF are significantly higher than the assay detection limits, and may reflect its activity as an endothelial cell (EC) survival factor (Ferrara, 2004). The early response involved an increase in both mRNA and protein after ligation, which paralleled a precipitous fall in blood flow and tissue PO2, and hence is probably in response to hypoxic conditions, well before any capillary growth. In contrast, the delayed response closely preceded the increase in C: F, and involved increased amount of VEGF protein in the face of a decreased VEGF transcript level.

Early response

The observation of a concurrent increase in VEGF mRNA and protein levels during the acute phase of ischaemia (1 and 3 days after ligation) is in agreement with previous studies (Couffinhal et al. 1998; Cherwek et al. 2000; Silvestre et al. 2001; Luo et al. 2002; Rissanen et al. 2002) which reported increases within days after surgery to induce severe hindlimb ischaemia in mice, rats and rabbits. The initial increase in VEGF is probably stimulated by muscle hypoxia due to the abrupt reduction in perfusion. In the current study, muscle blood flow at rest was decreased for the first few days after iliac ligation to 30% of control values, and this hypoperfusion was greater in contracting muscles. These findings are replicated at the level of microcirculation, where capillary perfusion showed a great intermittency 3 and 7 days after ligation, and there was no increase in red cell velocity in contracting muscles (Anderson et al. 1997). The ensuing hypoxia could upregulate VEGF at both transcriptional and translational levels, either involving the hypoxia-inducible transcription factor 1 (HIF-1) which accumulates under low oxygen tension (Forsythe et al. 1996), by stabilization of VEGF mRNA which is dependent on the RNA-binding protein HuR (Ikeda et al. 1995), or by translation via an alternative ribosome entry site (Stein et al. 1998), and the increased protein expression may act as a positive feedback via Akt/NO to increase VEGF mRNA (Ferrara, 2004). Indeed, a discrepancy between mRNA and protein levels suggests a post-translation regulatory step in a cancer model, with VEGF being post-translationally cleaved by matrix metalloproteinase (MMPs) (Lee et al. 2005).

In studies using models of severe ischaemia, an early increase in VEGF has been directly associated with rapid capillary growth, but VEGF expression was clearly linked to the presence of inflammatory mononuclear cell infiltration (Couffinhal et al. 1998; Luo et al. 2002; Rissanen et al. 2002) and degenerating/regenerating muscle fibres (Rissanen et al. 2002). In our model where inflammatory muscle damage does not occur, and there is no evidence of macrophage infiltration to account for the increase in VEGF (Brown et al. 2003), there was no capillary growth at this time despite the elevation of levels of VEGF mRNA and protein. This suggests that VEGF alone is not sufficient to stimulate angiogenesis under these conditions. Indeed, even when VEGF levels are high the angiogenic outcome appears to be dependent on expression of Flk-1, but not Flt-1 (Milkiewicz et al. 2003).

Delayed response

Seven days after iliac artery ligation, the levels of both VEGF mRNA and protein did not differ from controls, even though muscle blood flow remained impaired, and intermittency of capillary perfusion and muscle surface PO2 are still lower than normal at this time (Anderson et al. 1997; Dawson et al. 1990). Importantly, there was no capillary growth at this time. A similar lack of change in mRNA for VEGF was seen in rat hindlimb muscles after femoral artery ligation without necrosis (Lloyd et al. 2003), while an initial large increase in hindlimb muscle VEGF protein after dissection of the femoral artery in rabbits gradually declined, and there was no increase in capillary supply in both soleus and tibialis anterior (Cherwek et al. 2000). Thus, hypoxia may be important in the elevation of VEGF mRNA and protein during the first 3 days but, in the absence of inflammation, may not be an adequate stimulus for either VEGF or capillary growth one week after iliac artery ligation. This may be related to the influence of anti-inflammatory products such as heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1) that enhances ischaemic tolerance in skeletal muscles, and promotes VEGF-driven non-inflammatory angiogenesis that facilitates tissue repair (Bussolati et al. 2004). Clearly, VEGF upregulation could be in response to many other factors including elevated NO levels, possibly countering the hypoxic response via HIF to transactivate the VEGF release promoter, or increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by leucocytes, via the xanthine oxidase system. However, we know that eNOS protein is lowered after 35 days (Brown et al. 2003), so the role of NO is likely to be marginal, and HIF-1 was increased by arterial ligation in mice (Milkiewicz et al. 2005), but ROS does appear to be implicated in the endothelial response to muscle ischaemia (Garnham & Hudlicka, 1996).

The second phase of the VEGF response to ischaemia occurred between 14 and 35 days, and exhibited paradoxical discrepancy between mRNA, which decreased below normal, and protein levels, which showed a modest rise. The observed decrease in mRNA is in agreement with reports on cultured heart and liver cells exposed to chronic hypoxia (Levy, 1999). Similarly, in mouse ischaemic muscles an early increase in VEGF message, identified by in situ hybridization, was followed by a weaker signal after 14 days, which became undetectable 21 days after femoral artery ligation (Couffinhal et al. 1998). A decreased mRNA expression does not necessarily imply a suppressed transcription of VEGF, but may be explained by post-transcriptional regulation of the VEGF gene via stabilization of its mRNA (Stein et al. 1995), and/or an alternative way of translation via an active internal ribosome entry site (IRES) that is maintained at a low cellular oxygen tension (Stein et al. 1998). Translation of most eukaryotic mRNAs involves interaction of mRNA 5′cap with the eIF4E (eukaryotic initiation factor 4E) peptide, and as hypoxia decreases the availability of eIF4E, the total protein production is reduced (Kraggerud et al. 1995). Thus, to preserve sufficient levels of VEGF protein in a setting of sustained ischaemia, when cap-dependent translation is compromised due to a reduced level of the eIF4E complex, VEGF mRNA may be translated more efficiently via internal ribosome entry site (IRES).

The gradual secondary increase in level of VEGF protein, either from production or release from extracellular stores, coincided with the late proliferation of capillary endothelial cells and increase in capillary to fibre ratio (Fig. 4; Brown et al. 2003; Milkiewicz et al. 2003). It is not possible to detect on the basis of Western analysis where the source of VEGF is in ischaemic muscles, but VEGF immunostaining was localized to capillaries (Milkiewicz et al. 2003), as also seen in biopsies from patients with intermittent claudication and similar mild-to-moderate ischaemia (Brown et al. 2002), and the expanded capillary bed may contribute to the rise in VEGF. The increase in protein may be more modest than immediately after iliac ligation because of amelioration of muscle hypoxia by the development of collateral circulation. There was partial restoration of blood flow at 14 and 35 days, with a concomitant increase in tissue PO2, even though nutritive perfusion at the microcirculatory levels will still be impaired because of the attenuated dilator reactivity of precapillary arterioles (Dawson et al. 1990; Kelsall et al. 2001). The gradual return to control values of muscle fatiguability by 5 weeks also probably reflects the progressive recovery of blood flow through collateral circulation, supporting any metabolic adaptation to ischaemia. Angiogenesis may also be delayed because the reduced blood flow during the first two weeks post-ligation impairs generation of nitric oxide which is involved in the mediation of VEGF-induced angiogenesis (Milkiewicz et al. 2005). Changes in fibre area show the same relative change as seen for EDL/BM ratio, demonstrating that the observed increase in capillarity could not be explained by muscle atrophy, nor could reduced diffusion distance explain the increased tissue oxygenation independent of the rise in C: F.

Conclusions

The present study shows that although VEGF mRNA and protein expression are significantly upregulated by an abrupt reduction in skeletal muscle perfusion due to iliac artery ligation in the rat, this is insufficient to induce angiogenesis immediately. During prolonged ischaemia, which occurs without tissue damage or inflammation, they are modulated differently at transcriptional and post-transcriptional levels. The attenuation of VEGF mRNA levels over time indicates that these may not be as useful as previously thought as an index of angiogenic potential in response to ischaemic insult. Finally, sequential increases in VEGF receptor expression and cellular proliferation give rise to an overt angiogenic response, leading to improved muscle oxygenation and performance, demonstrating that activation of a multicomponent cascade is required for the functionally relevant outcome.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the British Heart Foundation (PG 99106) and the Rowbotham Bequest.

References

- Anderson SI, Hudlicka O, Brown MD. Capillary red blood cell flow and activation of white blood cells in chronic muscle ischemia in the rat. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H2757–H2764. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.6.H2757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Askew CD, Green S, Walker PJ, Kerr GK, Green AA, Williams AD, Febbraio MA. Skeletal muscle phenotype is associated with exercise tolerance in patients with peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:802–807. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2005.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baum O, Djonov V, Ganster M, Widmer M, Baumgartner I. Arteriolarization of capillaries and FGF-2 upregulation in skeletal muscles of patients with chronic peripheral arterial disease. Microcirculation. 2005;12:527–537. doi: 10.1080/10739680591003413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MD, Kent J, Kelsall CJ, Milkiewicz M, Hudlicka O. Remodeling in the microcirculation of rat skeletal muscle during chronic ischemia. Microcirculation. 2003;10:179–191. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown MD, Verhaeg J, Milkiewicz M, Lamont P, Stewart A. Capillarity and vascular endothelial growth factor in calf biopsies from patients with intermittent claudication after a supervised exercise programme. J Vasc Res. 2002;39(Suppl. 1):45. abstract. [Google Scholar]

- Bussolati B, Ahmed A, Penberton H, Landis RC, DiCarlo F, Haskard DO, Mason JC. Bifunctional role for VEGF-induced heme oxygenase-1 in vivo: induction of angiogenesis and inhibitionof leucocytic infiltration. Blood. 2004;103:761–766. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-06-1974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherwek DH, Hopkins MB, Thompson MJ, Annex BH, Taylor DA. Fiber type-specific differential expression of angiogenic factors in response to chronic hindlimb ischemia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2000;279:H932–H938. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2000.279.3.H932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne CA, Weller RO, Bradley WG, Silber DI, O'Donnell TF, Jr, Callow AD. Ultrastructural and capillary adaptation of gastrocnemius muscle to occlusive peripheral vascular disease. Surgery. 1982;92:434–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Couffinhal T, Silver M, Zheng LP, Kearney M, Witzenbichler B, Isner JM. Mouse model of angiogenesis. Am J Pathol. 1998;152:1667–1679. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson JM, Okyayuz-Baklouti I, Hudlicka O. Skeletal muscle microcirculation: the effects of limited blood supply and treatment with torbafylline. Int J Microcirc Clin Exp. 1990;9:385–400. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. Vascular endothelial growth factor: basic science and clinical progress. Endocr Rev. 2004;25:581–611. doi: 10.1210/er.2003-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe JA, Jiang BH, Iyer NV, Agani F, Leung SW, Koos RD, Semenza GL. Activation of vascular endothelial growth factor gene transcription by hypoxia-inducible factor 1. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4604–4613. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garnham A, Hudlicka O. Effect of allopurinol and vitamin E on leucocyte rolling and adhesion in chronically ischaemic muscles. Int J Microcirc. 1996;15:202. [Google Scholar]

- Hudlicka O, Brown MD, Egginton S, Dawson JM. Effect of long-term electrical stimulation on vascular supply and fatigue in chronically ischemic muscles. J Appl Physiol. 1994;77:1317–1324. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1994.77.3.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikeda E, Achen MG, Breier G, Risau W. Hypoxia-induced transcriptional activation and increased mRNA stability of vascular endothelial growth factor in C6 glioma cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:19761–19766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.34.19761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelsall CJ, Brown MD, Hudlicka O. Alterations in reactivity of small arterioles in rat skeletal muscle as a result of chronic ischaemia. J Vasc Res. 2001;38:212–218. doi: 10.1159/000051049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraggerud SM, Sandvik JA, Pettersen EO. Regulation of protein synthesis in human cells exposed to extreme hypoxia. Anticancer Res. 1995;15:683–686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Jilani SM, Nikolova GV, Carpizo D, Iruela-Arispe ML. Processing of VEGF-A by matrix metalloproteinases regulates bioavailability and vascular patterning in tumors. J Cell Biol. 2005;169:681–691. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200409115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levy AP. A cellular paradigm for the failure to increase vascular endothelial growth factor in chronically hypoxic states. Coron Artery Dis. 1999;10:427–430. doi: 10.1097/00019501-199909000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd PG, Prior BM, Yang HT, Terjung RL. Angiogenic growth factor expression in rat skeletal muscle in response to exercise training. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2003;284:H1668–H1678. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00743.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo F, Wariaro D, Lundberg G, Blege H, Wahlberg E. Vascular growth factor expression in a rat model of severe limb ischemia. J Surg Res. 2002;108:258–267. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2002.6551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga T, Warltier DC, Weihrauch DW, Moniz M, Tessmer J, Chilian WM. Ischemia-induced coronary collateral growth is dependent on vascular endothelial growth factor and nitric oxide. Circulation. 2000;102:3098–3103. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.25.3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaren M, Newton DJ, Khan F, Belch JJ. Vascular endothelial growth factor in patients with critical limb ischemia before and after amputation. Int Angiol. 2002;21:165–168. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Hudlicka O, Brown MD, Silgram H. Nitric oxide, VEGF and VEGFR-2: interactions in activity-induced angiogenesis in rat skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2005;289:H336–H343. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01105.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Milkiewicz M, Hudlicka O, Verhaeg J, Egginton S, Brown MD. Differential expression of Flk-1 and Flt-1 in rat skeletal muscle in response to chronic ischaemia: favourable effect of muscle activity. Clin Sci. 2003;105:473–482. doi: 10.1042/CS20030035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rissanen TT, Vajanto I, Hiltunen MO, Rutanen J, Kettunen MI, Niemi M, Leppanen P, Turunen MP, Markkanen JE, Arve K, Alhava E, Kauppinen RA, Yla-Herttuala S. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-2 (KDR/Flk-1) in ischemic skeletal muscle and its regeneration. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1393–1403. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62566-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre JS, Mallat Z, Tamarat R, Duriez M, Tedgui A, Levy BI. Regulation of matrix metalloproteinase activity in ischemic tissue by interleukin-10: role in ischemia-induced angiogenesis. Circ Res. 2001;89:259–264. doi: 10.1161/hh1501.094269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein I, Itin A, Einat P, Skaliter R, Grossman Z, Keshet E. Translation of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by internal ribosome entry: implications for translation under hypoxia. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:3112–3119. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.6.3112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein I, Neeman M, Shweiki D, Itin A, Keshet E. Stabilization of vascular endothelial growth factor mRNA by hypoxia and hypoglycemia and coregulation with other ischemia-induced genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5363–5368. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.10.5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang GL, Chang DS, Sarkar R, Wang R, Messina LM. The effect of gradual or acute arterial occlusion on skeletal muscle blood flow, arteriogenesis, and inflammation in rat hindlimb ischemia. J Vasc Surg. 2005;41:312–320. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuomisto TT, Rissanen TT, Vajanto I, Korkeela A, Rutanen J, Yla-Herttuala S. HIF-VEGF-VEGFR-2, TNF-alpha and IGF pathways are upregulated in critical human skeletal muscle ischemia as studied with DNA array. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:111–120. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]