Abstract

Severe forms of anemia in children in the developing countries may be characterized by different clinical manifestations at particular stages of development. Whether this reflects developmental changes in adaptation to anemia or other mechanisms is not clear. The pattern of adaptation to anemia has been assessed in 110 individuals with hemoglobin (Hb) E β-thalassemia, one of the commonest forms of inherited anemia in Asia. It has been found that age and Hb levels are independent variables with respect to erythropoietin response and that there is a decline in the latter at a similar degree of anemia during development. To determine whether this finding is applicable to anemia due to other causes, a similar study has been carried out on 279 children with severe anemia due to Plasmodium falciparum malaria; the results were similar to those in the patients with thalassemia. These observations may have important implications both for the better understanding of the pathophysiology of profound anemia in early life and for its more logical and cost-effective management.

Keywords: erythropoietin, malaria, thalassemia, hemoglobin

There is increasing evidence that some particularly severe forms of anemia that affect children in the developing countries are characterized by different clinical manifestations at particular stages of development. However, the extent to which this observation reflects fundamental changes in adaptation to anemia or other factors is not clear. Nor have the clinical implications of these developmental changes been determined. They have been particularly well documented in the case of Hb E β-thalassemia and the often profound forms of anemia that occur in children with malaria due to infection by P. falciparum.

As a result of the extremely high gene frequencies for both β-thalassemia and hemoglobin (Hb) E in many Asian populations, the disease caused by the compound heterozygous inheritance of both genes, Hb E β-thalassemia, is the commonest severe form of thalassemia in parts of India, Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, and Indonesia and probably in several other countries in Southeast Asia (1). In Thailand, for example, it is estimated that there are ≈3,250 babies born with this condition each year and that there are 100,000 patients in the population; the median survival is ≈30 years (2).

Because the mutation that produces Hb E results in the activation of a cryptic splice site in the β-globin gene, it is synthesized at a reduced rate and hence behaves like a mild form of β-thalassemia (1, 3). Hb E β thalassemia has a remarkably variable phenotype, ranging from transfusion-dependent anemia from early in life to a disorder characterized by moderate anemia that is compatible with adequate growth, development, and function (1, 4). Although some of this phenotypic variability is due to the action of different β-thalassemia mutations or modifier genes, much of it remains unexplained (5–7). Recent longitudinal studies of affected children in Sri Lanka have emphasized the remarkable instability of their phenotypes, particularly over the first 10 years of life, during which there was a variable and changing pattern of anemia, erythroid expansion, and associated growth failure. By contrast, the phenotype became more stable later in development, and it was possible to stop blood transfusion in a proportion of older patients, with no deleterious effects on their further development and function (7).

Malaria currently results in two million deaths each year, many in childhood (8). The changing pattern of the clinical manifestations of acute Plasmodium falciparum malaria infection during development has been well documented and appears to be similar in many countries in which there is a high frequency of infection. In the early years of life, the main feature is severe anemia, whereas, in older children, the pattern changes; anemia becomes less severe and is replaced by cerebral malaria and other complications. Severe respiratory distress also seems to be commoner in early life (9, 10).

Here, we have analyzed the response to anemia at different ages in patients with Hb E β-thalassemia. The results suggest that age and Hb levels are independent variables in terms of erythropoietin (Epo) response and that there is a decline in the level of the latter at a similar degree of anemia during development. To determine whether these findings are peculiar to this condition or whether they have more general implications,, we carried out a similar study on a group of patients with severe anemia due to P. falciparum malaria. The pattern of response was similar to that observed in Hb E β-thalassemia. These observations may have important implications for the management of both these conditions and for other common forms of severe childhood anemia.

Results

Hb E β-Thalassemia.

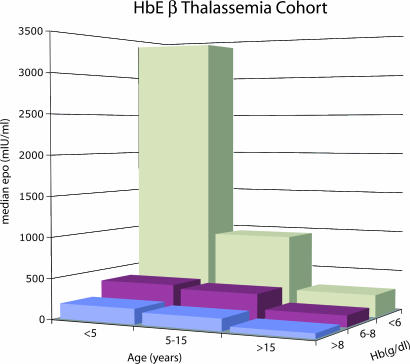

The clinical and hematological findings in 110 patients were assessed for at least 2–3 years. The Hb concentrations ranged from 3.1–8.3 g/dl The results of plasma Epo assays, carried out over the period of observation, are shown in Figs. 1 and 2. There was a strong correlation between Epo and Hb level (P = 0.0001) and also a decline in Epo response to anemia with age (P = 0.0001). Multiregression analysis indicated that age and Epo response to anemia are independent variables, with a significantly higher response to a particular Hb level in younger age groups (P = 0.0001) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Histogram showing the median Epo level for patients in the Hb E β-thalassemia cohort grouped according to age and Hb level.

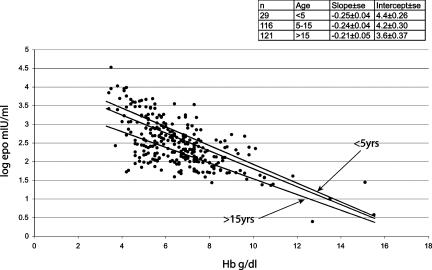

Fig. 2.

Scattergram showing the relationship of Epo (log transformed) to Hb levels in the Hb E β-thalassemia cohort. Fitted values for ages <5, 5–10, and >10 years are shown. (Inset) The number of patients in each age group and the slopes and intercept of each regression line. Calculated standard errors are adjusted for multiple estimations from each patient.

Fig. 2 also shows the relationship of Hb levels to Epo in different age groups. It appears that younger children had higher Epo levels at all degrees of anemia. For example, children <5 years of age had >6-fold higher Epo levels compared with children >10 years of age. In comparison, there was very little difference between age groups of the proportional effect of changes in Hb. For example, Epo levels dropped by 56% for every gram rise in Hb in children <5 years of age, compared with 62% in children aged >10 years.

To determine the extent to which the Epo response to anemia was reflected in an increased red cell mass, the level of soluble transferrin receptor (Str) was measured. The overall range was 67–581 nmol/liter (normal = 10–30 nmol/liter). There was a significant positive association between the level of Epo and Str (P = 0.006; coefficient 0.0025 95% CI 0.001–0.004). Multiple regression analysis comparing serum Epo (log transformed) against Str adjusted for age and Hb level also indicated a significant positive correlation between serum Epo and Str (P = 0.012; coefficient 0.0016 95% CI 0.0004–0.0029).

To determine whether the increase in red cell mass was reflected by the rate of enlargement of the spleen in patients aged 15 years or less, multiple measurements of the spleen tip, in centimeters, below the left costal margin were made by the same observer at least three times each year. In those in the mild class, the mean increase in size was 0.05 cm/month, whereas, in the more severely affected group, it was 0.28 cm/month. The mean Hb values in the mild and severe groups were 6.2 and 5.3 g/dl, respectively. Multiple regression analysis adjusted for Hb and age and allowing for multiple measurements from each individual, indicated that the severe cases had an Epo level of ≈2.8-fold greater than the mild group (95% CI 1.5–5.2; P = 0.003). Further comparison of the two groups suggested that the severe cases had similar Epo responses to the entire cohort, whereas the mild group's response was lower than predicted.

Because patients with Hb E β-thalassemia have elevated levels of Hb F, and because the differences in oxygen affinity between Hb A and Hb F might affect Epo responses, the levels of Hb F were determined by HPLC analysis. The range was 6–60% (mean 28.4%, SD 10.4) or 0.4–3.5 g/dl (mean 1.72, SD 0.8). There was no significant difference between the range or means of Hb F with increasing age; in 32 patients in the 1- to 10-yr range, the mean level of Hb F was 28.0% (1.5 g/dl), in the 10- to 20-yr range, 26.4% (1.5 g/dl), and in the 20- to 30-yr range, 29.1% (1.8 g/dl).

During the course of the study, the thalassemic patients underwent regular analysis of their serum ferritin levels to monitor their body iron burdens. There was no relationship between the Epo and plasma ferritin levels. In three patients who were receiving deferoxamine therapy to reduce their body iron burdens, serial Epo estimations before and for 3 days after administration of deferoxamine showed no significant change in Epo level.

Malaria.

Of the 279 children with malaria, 126 had severe malarial anemia (SMA) as defined by WHO, that is, a Hb level of <5 g/dl, 68 had coma, reflecting cerebral malaria, and 8 had both SMA and coma.

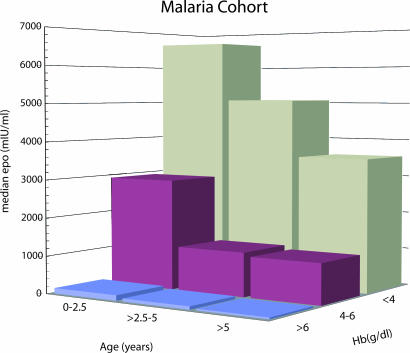

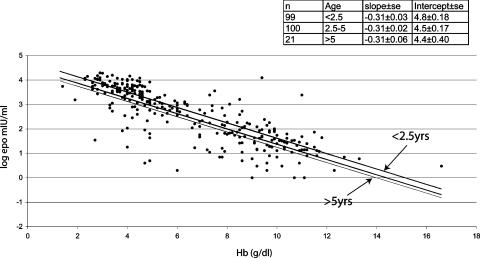

The Hb concentrations for the entire group ranged from 1.1–16.6 g/dl and the plasma Epo concentrations from 1–19,600 mIU/ml. There was a strong correlation between plasma Epo concentration and age (P < 0.001) and Hb level (P < 0.001). Multiple-regression analysis indicated that age and Hb level were independent variables with respect to Epo concentration, as in the case of the thalassemic children, suggesting a decline in Epo response to a particular degree of anemia during development (Figs. 3 and 4). Fig. 4 shows the relationship between Epo and Hb level in three different age groups. As in the thalassemic children, younger children tended to have higher Epo levels at all degrees of anemia. For example, children <2.5 years of age had an ≈2-fold increase in Epo compared with children >5 years of age, whereas there was no difference in the effect of changes in Hb level between different ages.

Fig. 3.

Histogram showing the median Epo level for children in the malaria cohort grouped according to age and Hb level.

Fig. 4.

Scattergram showing the relationship of Epo (log transformed) to Hb levels in the malaria cohort. Fitted values for ages <2.5, 2.5–5, and >5 years are shown. (Inset) The number of children in each age group and the slopes and intercept of each regression line.

The Epo levels in the different classes of severe manifestations of malaria are summarized in Table 1. The 68 children with cerebral malaria were significantly older than those with SMA, and their Hb levels were significantly higher, and their Epo levels lower, than those with SMA alone. Linear regression analysis showed a significant correlation between the plasma Epo concentration and the duration of the illness (P = 0.003), the coma score (P = 0.001), and the serum creatinine level (P = 0.002). There was no correlation between the level of Epo and the degree of parasitemia (P = 0.21), serum lactate (P = 0.13), or serum bicarbonate (P = 0.91).

Table 1.

Plasma Epo concentration according to severe manifestations of malaria

| Clinical group | n | Hb, g/dl median [IQR] | Epo, mIU/ml median [IQR] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Children with SMA only | 117 | 4.0 (3.4–4.5) [1.4–4.9] | 3,970 (1,587–6,590) [4–19,600] |

| Children with cerebral malaria only | 68 | 8.6 (7.3–9.6) [5.8–11.6] | 93 (14.3–431) [1–11,600] |

| Children with SMA and coma | 8 | 3.5 (2.7–4.6) [2.6–4.8] | 4,540 (697–7,224) [213–11,600] |

IQR, interquartile range.

Because previous studies have shown a high frequency of α-thalassemia in these children (11), the Epo response was compared between normal children and those with different α-thalassemia genotypes. No significant correlations were observed.

Discussion

This study suggests that, despite completely different underlying causal mechanisms, two common forms of profound anemia affecting patients in the developing countries are associated with similar age-related adaptive changes with respect to Epo response. In each case, both age and Hb levels were independent variables, indicating a reduced Epo response for a particular Hb level at different ages. The effect of age on Epo appears to be independent of the degree of anemia in both cohorts, suggesting that age has a direct effect on the background level of Epo production.

There have been two previous reports of Epo responses to anemia in Hb E β-thalassemia (12, 13); in one, there appeared to be a difference in the overall pattern of response between children and adults, although this did not reach statistical significance (13). In a study of Epo response in patients with sickle cell anemia, 10 adults seemed to show a lower Epo response at approximately the same Hb level as those of children at the same level (14). Although there have been no extensive studies of Epo response at different age groups in patients with profound anemia of the same etiology, particularly early in life, longitudinal analysis of individuals with milder forms of anemia due to different causes have given inconsistent results; in some cases there seems to have been some blunting of response in older patients (15), whereas, in others, the response appeared to be similar across the age range (16, 17).

Of course, it is still possible that the varying Epo response with respect to age in patients with Hb E β-thalassemia could be a reflection of this particular disease, although the finding of a similar response in the malaria cohort makes this much less likely. Furthermore, no factors that might blunt Epo response with increasing age in this condition have been identified so far. There was no significant change in the level of Hb F with increasing age in these patients. Furthermore, previous studies of patients with β-thalassemia have concluded that Hb F exerts an independent regulatory effect on Epo production and erythropoiesis that is detectable only when Hb F levels exceed 40% (18), a level that was achieved by very few patients in this study. Although transient increases in Epo levels have been described after the administration of deferoxamine, an iron chelator, to normal people, indicating a role for iron in the regulation of Epo response (19), there was no relationship between the serum ferritin levels and Epo response in this study, and no changes in Epo levels were observed after the administration of deferoxamine to these patients. There is no evidence of progressive renal insufficiency in patients with Hb E β-thalassemia; in any case, this would be a very unlikely cause for the variations in Epo response that were seen in the younger age groups.

The change in phenotype of severe malaria in this study, in which SMA was commoner in the very young children and replaced later by a higher frequency of cerebral malaria, is similar to that reported in Africa and other malarious areas (9, 10). The pathogenesis of the anemia of malaria is complex and multifactorial (20). The reason why SMA occurs more commonly very early in life is still not clear, although it has been suggested that one factor may be the inability of very young children to maintain IL-10 production in response to an inflammatory process (21). Although one report suggested a suboptimal Epo response to the anemia of malaria, it did not include studies of patients under the age of 15 years (22); other studies, that included children, have described an adequate response (23). In this study, there was an extremely high response, comparable with that in the children with thalassemia. A highly significant decline in Epo production related to age and independent of Hb level was clearly defined during the first 13 years of life. Maximum Epo response occurred very early and at a time when cerebral malaria was uncommon; there was a highly significant difference in Epo levels between those with SMA and coma, presumably, at least in part, reflecting the higher Hb levels in the latter.

Currently, very little is known about potential cellular mechanisms for age-related response to hypoxia. Interestingly, in in vitro studies age-related impaired angiogenesis has been related to decreased levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and to reduction in hypoxia-induced VEGF expression and HIF-1 activity, a major factor in Epo response to hypoxia (24).

These developmental changes in Epo responsiveness to severe anemia, if confirmed, may have important implications, at least for the clinical management of the two extremely common forms of anemia described in this study. The very high Epo response in early childhood and its decline with age in the case of Hb E β-thalassemia may be in part responsible for some of the phenotypic instability seen in this disorder during the early years of life (7). The lower level of Epo response compared with the entire cohort in the group of children with mild phenotypes is of particular interest in this respect. Although some genetic modifiers that reduce the severity of the phenotype in these children have been identified (6, 7), in many cases, the reason for the milder course of the disease is not clear. The possibility that this could be related to inherent differences in Epo response remains to be determined.

High levels of Epo production in thalassemia are an adaptive response to severe anemia and, hence, result in considerable expansion of the erythroid mass (25), as reflected by the Str data and rates of increase of the spleen size in this study. Because there is a major degree of ineffective erythropoiesis in all severe forms of β-thalassemia, the effect of extremely high levels of Epo on increasing the Hb level are limited, whereas at the same time they are responsible for many of the distressing complications of the disease, including increasing hepatosplenomegaly and bone deformity (1). If the Epo response at a particular Hb level is declining with age, the drive to erythroid expansion will also diminish. Hence, if the magnitude of the Epo response can be suppressed by transfusion during early life at times of maximum production, these complications might be avoided. It follows that it should be possible to stop transfusion, at least in a significant number of patients, at a time when the Epo response is reduced, certainly in conditions like Hb E β-thalassemia, in which the base-line Hb level is consistent with adequate function. Indeed, in the patients described in this study it was possible to stop transfusion in 37 patients aged between 9 and 50 years without any deleterious effect (7). A program of transient transfusion of this type would save badly needed resources in the developing countries in which this disease is so common.

The high frequency of SMA and the particularly high Epo responses in very early life may also have clinical implications for an understanding of the pathophysiology of severe malaria in early childhood and also the potential for different approaches to therapy. In view of recent evidence that Epo crosses the blood/brain barrier and protects against experimental brain injury and acts in other tissues as a tissue-protective cytokine (26, 27), the low frequency of brain damage and associated cerebral malaria in very young children at times of maximal Epo response is of considerable interest. A recent report has described how the administration of recombinant human Epo prevented death of mice with cerebral malaria due to P. berghei infection (28). Clearly, the potential neuroprotective effect of the extremely high levels of Epo produced in response to malaria in very young children requires further study.

Patients and Methods

Hb E β-Thalassemia.

The study group comprised 110 patients with Hb E β-thalassemia who were attending the National Thalassaemia Centre, Kurunegala, Sri Lanka. Their ages ranged from 1 to 54 years; 74 were <20 years old. The criteria by which they were divided into mild and severe classes included a linear quality-of-life scale, height, weight, growth velocity, skeletal development, spleen size, and Hb level and are described elsewhere (7). In addition to a remarkable degree of clinical heterogeneity at presentation, there was also considerable phenotypic variation over the period of study; of the 13 changes of severity-class assignment, 12 occurred in children under the age of 15 and all but one from the mild to the severe classes (7).

Blood samples for this study were obtained during routine hematological investigations carried out over 2–3 years. In the case of Epo analysis, in 86 cases, multiple estimations were carried out over the period of study; the remainder had a single estimation. Sixty-one of the patients were not receiving blood transfusions throughout the period of study, whereas the remainder were receiving occasional or regular transfusion. In the majority of the latter, Epo estimations were carried out during the period of observation before regular transfusion; none were performed within a month of transfusion.

Malaria.

This investigation was carried out on 279 children with malaria attending the pediatric ward of Madang Hospital on the north coast of Papua, New Guinea. Their ages ranged from 2.5 months to 13 years. The definition of severe malaria, based on World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, together with an analysis of the globin genes of these children, has been reported (11). Coma was assessed by using the Blantyre Coma Score and was defined as a score of ≤2 in children with asexual stages of P. falciparum in the peripheral blood and no evidence of bacterial or viral meningoencephalitis. SMA was defined as a febrile illness with a Hb level of <5 g/dl and an asexual P. falciparum parasitemia. The median duration of illness before admission was 4 days.

Methods.

A venous blood sample was collected in EDTA and lithium heparin. Hematological data were obtained from the EDTA sample (Coulter MD8; Coulter Electronics, Luton, U.K.). For the malariological studies, thick and thin blood films were also prepared, stained with Giemsa, and examined for the presence of malarial parasites. P. falciparum density per microliter of whole blood was calculated by using the measured white cell count. Blood samples were centrifuged and the plasma removed and stored in 500-μl aliquots at −20°C. Biochemical data were obtained by dry-slide chemistry (Ektachem; Eastman Kodak, Rochester, NY) in plasma obtained from the heparinized blood samples.

An aliquot of each sample was shipped to Oxford on dry ice and stored at −70°C. Duplicate plasma Epo concentrations were measured by ELISA (Quantikine in vitro Diagnostics kit, R & D Systems, Abingdon, U.K.) in plasma obtained from the EDTA blood samples. For samples obtained for the thalassemia study, Hb analysis and Hb F (HbF) estimations were performed by cation-exchange HPLC (Variant Analyzer; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) by using the β-thalassemia short program. The further characterization of the β-thalassemia mutations in the Sri Lankan children with Hb E β-thalassemia by DNA analysis has been reported (6). The level of Str was estimated by using an ELISA (R & D Systems).

Statistical Methods.

Epo levels were log10 transformed to normalize the Epo distribution. The effects of continuous variables on log10 Epo were explored by univariate linear regression. The effect of age and Hb were analyzed by using multiple regression, adjusted for multiple sampling of each individual. For each cohort, individuals were divided into three age groups so that the effect of changes of Hb levels on Epo could be compared between them, and appropriate regression coefficients (slopes and intercepts) estimated. Because of low numbers and a possible nonlinearity in the relationship between Epo and Hb at normal Hb levels, results were reanalyzed excluding individuals with Hb >10 g/dl; however, no differences were observed.

Ethical Approval.

Ethical approval for these studies was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the University of Colombo, the Medical Research Advisory Committee, Government of Papua New Guinea, the Central Oxford Research Ethics Committee, and the Oxford Tropical Research Ethics Committee.

Acknowledgments

We thank Liz Rose for invaluable help in preparing this manuscript. This study was supported by the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council.

Abbreviations

- Epo

erythropoietin

- Hb

hemoglobin

- SMA

severe malarial anemia

- Str

soluble transferrin receptor.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Weatherall DJ, Clegg JB. The Thalassaemia Syndromes. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Weatherall DJ, Akinyanju O, Fucharoen S, Olivieri NF, Musgrove P. In: Disease Control Priorities in Developing Countries. Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, Jha P, Mills A, Musgrove P, editors. New York and Washington, DC: Oxford Univ Press and the World Bank; 2006. pp. 663–680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Orkin SH, Kazazian HH, Antonarakis SE, Ostrer H, Goff SC, Sexton JP. Nature. 1982;300:768–769. doi: 10.1038/300768a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fucharoen S, Winichagoon P. Hemoglobin. 1997;21:299–319. doi: 10.3109/03630269709000664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Winichagoon P, Thonglairoam V, Fucharoen S, Wilairat P, Fukimaki Y, Wasi P. Br J Haematol. 1993;83:633–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.1993.tb04702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fisher CA, Premawardhena A, de Silva S, Perera G, Rajapaksa S, Olivieri NA, Old JM, Weatherall DJ. Br J Haematol. 2003;121:662–671. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04346.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Premawardhena A, Fisher CA, Olivieri NF, de Silva S, Arambepola M, Perera W, O'Donnell A, Peto TEA, Viprakasit V, Merson L, et al. Lancet. 2005;366:1467–1470. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67396-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. The World Malaria Report. Geneva: WHO; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Marsh K, Forster D, Waruiru C, Mwangi I, Winstanley M, Marsh V, Newton C, Winstanley P, Warn P, Peshu N, et al. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1399–1404. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505253322102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Newton CR, Krishna S. Pharmacol Ther. 1998;79:1–53. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00008-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Allen SJ, O'Donnell A, Alexander NDE, Alpers MP, Peto TEA, Clegg JB, Weatherall DJ. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14736–14741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paritpokee N, Wiwanitkit V, Bhokaisawan N, Boonchalermvichian C, Preechakas P. Clin Lab. 2002;48:631–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sukpanichnant S, Opartkiattikul N, Fucharoen S, Tanphaichitr VS, Hasuike T, Tatsumi N. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1997;28(Suppl 3):134–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sherwood JB, Goldwasser E, Chilcote R, Carmichael LD, Nagel RL. Blood. 1986;67:46–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ershler WB, Sheng S, McKelvey J, Artz AS, Denduluri N, Tecson J, Taub DD, Brant LJ, Ferrucci L, Longo DL. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005;53:1360–1365. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.53416.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Powers JS, Krantz SB, Collins JC, Meurer K, Failinger A, Buchholz T, Blank M, Spivak JL, Hochberg M, Baer A, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1991;39:30–2. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb05902.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goodnough LT, Price TH, Parvin CA. J Lab Clin Med. 1995;126:57–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Galanello R, Barella S, Turco MP, Giagu N, Cao A, Dore F, Liberato NL, Guarnone R, Barosi G. Blood. 1994;83:561–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ren X, Dorrington KL, Maxwell PH, Robbins PA. J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:680–686. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.2.680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackintosh CL, Beeson JG, Marsh K. Trends Parasitol. 2004;20:597–603. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2004.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nussenblatt V, Mukasa G, Metzger A, Ndeezi G, Garrett E, Semba RD. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2001;8:1164–1170. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.8.6.1164-1170.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burgmann H, Looareesuwan S, Kapiotis S, Viravan C, Vanijanonta S, Hollenstein U, Wiesinger E, Presterl E, Winkler S, Graninger W. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1996;54:280–283. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.54.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Burchard GD, Radloff P, Philipps J, Nkeyi M, Knobloch J, Kremsner PG. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1995;53:547–551. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1995.53.547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivard A, Berthou-Soulie L, Principe N, Kearney M, Curry C, Branellec D, Semenza GL, Isner JM. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:29643–29647. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001029200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huebers HA, Beguin Y, Pootrakul P, Einspahr D, Finch CA. Blood. 1990;75:102–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brines ML, Ghezzi P, Keenan S, Agnello D, de Lanerolle NC, Cerami C, Itri LM, Cerami A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10526–10531. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.19.10526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ghezzi P, Brines M. Cell Death Differ. 2004;11(Suppl 1):S37–S44. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaiser K, Texier A, Ferrandiz J, Buguet A, Meiller A, Latour C, Peyron F, Cespuglio R, Picot S. J Infect Dis. 2006;193:987–995. doi: 10.1086/500844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]