For patients in Canada, 2 strategies may be initiated in the emergent treatment of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (MI) — primary percutaneous coronary intervention or fibrinolytic drug therapy. Regardless of which strategy is chosen, the successful reperfusion of the infarct-related artery in the shortest time is a key determinant of optimal patient outcomes.1 The recommendations for times to treatment include the following targets: (1) less than 30 minutes from arrival at the emergency department to fibrinolysis (door-to-needle time), (2) less than 90 minutes from arrival at the emergency department to primary percutaneous coronary intervention (door-to-balloon time) and (3) to avoid delays of more than 60 minutes to achieve percutaneous coronary intervention when fibrinolytic therapy could have been given.1 From an evolving body of evidence and international guidelines, increasing attention has been paid to reduce these times by advancing the diagnosis and treatment of ST-segment elevation MI to paramedics in the pre-hospital phase of care.1–3 Consequently, major stakeholders in providing care for ST-segment elevation MI are variably but actively collaborating with Emergency Medical Services (EMS) across Canada and elsewhere.

In this issue, de Villiers and colleagues describe a collaborative effort in their implementation of a pre-hospital diagnosis and transfer pathway for primary percutaneous coronary intervention.4 Their combined efforts resulted in an impressive 30-day mortality of only 3.1% among 358 patients who presented within 12 hours after symptom onset and who sought medical attention through EMS in the 16 months after introduction of the pathway. The dynamic partnership involving medical and EMS personnel focused on the pre-hospital diagnosis of ST-segment elevation MI and the subsequent activation of the catheterization laboratory for primary percutaneous intervention. Through intensive multidisciplinary collaboration, their pathway resulted in door-to-balloon times of less than 60 minutes among 49% of the patients and within the currently recommended 90 minutes among 79% of the patients. This impressive performance was conducted in Calgary, a large urban Canadian city with a contemporary EMS system and a leading national percutaneous coronary intervention program.

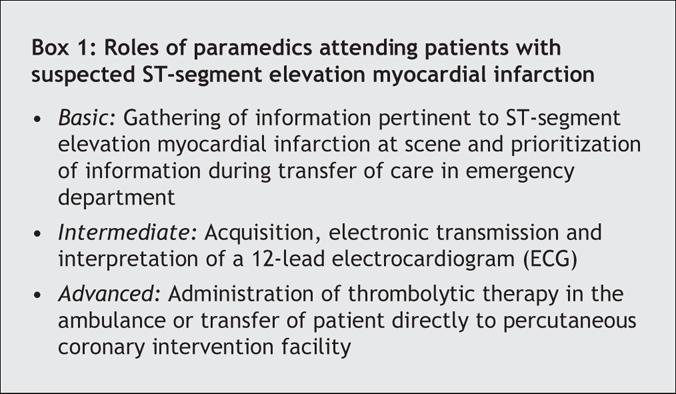

Replicating the results reported by de Villiers and colleagues in other centres requires an understanding of the basic and more advanced responsibilities of paramedics when faced with patients experiencing chest pain that may be due to an ST-segment elevation MI. With this understanding, several key strategies should be implemented to improve not only processes of care but invariably the clinical outcomes of patients.

A paramedic's most basic role in the care of a patient with chest pain is to obtain simple historical information that will improve both door-to-needle and door-to-balloon times (Box 1). This includes noting whether an acute coronary syndrome is suspected, determining symptom onset, completing a reperfusion checklist during transport (e.g., inclusion and exclusion criteria for either fibrinolysis or percutaneous coronary intervention) and prioritizing this information during patient handover at the hospital. Regrettably, such simple information is not routinely collected in Canada, or it is sometimes lost in the moment of transfer of care in a busy emergency department.

Box 1.

Intermediate-level roles assumed by paramedics include the acquisition and transmission of a pre-hospital electrocardiogram (ECG) that indicates ST-segment elevation, and advanced hospital notification. A recent meta-analysis revealed that the extra 1.2 minutes on average that paramedics took at the scene to complete an ECG led to a mean savings of 36.1 minutes in the door-to-needle time.5 Despite the strength of evidence supporting pre-hospital ECGs in reducing both door-to-needle and door-to-balloon times, many communities do not take advantage of this role. Many EMS systems simply do not have 12-lead ECG devices. For those that do have access to ECGs, many do not use them consistently or lack the ability to transmit the ECGs to emergency departments. In many communities that have pre-hospital ECG capabilities, the next link in the chain — a structured inflow and rapid interpretation of pre-hospital ECGs, followed by rapid activation of a treatment protocol for ST-segment elevation MI — is lacking or haphazardly implemented.

The administration of fibrinolytic therapy in the ambulance or transfer of the patient directly to the catheterization laboratory for percutaneous coronary intervention would be considered an advanced paramedic role. Both of these strategies have been successfully implemented in centres with contemporary EMS systems.6 Evidence from major clinical trials and registries have demonstrated excellent outcomes, including reduced mortality and aborted MIs, among patients who receive pre-hospital fibrinolysis,7,8 especially if treatment occurs within 2 hours of symptom onset. Outcomes among patients who receive treatment very rapidly are comparable with those among patients who present emergently for primary percutaneous coronary intervention.1,2,8 Pre-hospital fibrinolysis is a growing and feasible option in Canada, particularly in centres without timely access to cardiac catheterization facilities. These advanced roles promote the concept of initiating emergency cardiac care in the ambulance rather than in the emergency department, which alters our notion of “first medical contact.”

Centres considering pre-hospital fibrinolysis or expedited transfer for percutaneous coronary intervention must decide whom they consider to be first medical contact and when to start the “stopwatch” when monitoring their care processes. Should time intervals be calculated from arrival in the emergency department or at a predefined time during EMS transport? If the reperfusion decision were moved to the ambulance and EMS personnel were capable of administering fibrinolytic therapy, then perhaps the stopwatch should be started during the pre-hospital phase, with corresponding application of the guideline targets. The time savings achieved in the emergency department was considered by de Villiers and coauthors in their evaluation, but they did not account for potential delays in pre-hospital care in their analysis. They report a median time of 35 minutes (interquartile range 27–42) from EMS arrival at the scene to arrival at the emergency department and a median time of 97 minutes (interquartile range 76–124) from EMS arrival at the scene to establishment of coronary blood flow. If we consider EMS arrival as “first medical contact,” their strategy achieved reperfusion within the recommended 90 minutes in only 41% of the cases and not the 79% they report for the traditional door-to-balloon interval. Furthermore, if the paramedics were capable of providing fibrinolytic agents, or a fibrinolysis protocol was in place at the emergency department that could be activated by a pre-hospital ECG, treatment could be delivered very quickly. However, if they have to transport the patient to the catheterization laboratory, then the median transport time of 35 minutes plus the median transfer time of 32 minutes from emergency department to catheterization laboratory plus the median duration of 29 minutes for percutaneous coronary intervention would likely exceed the 60-minute threshold published in the guidelines.1 Lastly, given the time it took patients to call EMS (median 53 minutes) and the EMS transport time (median 35 minutes), there appears to be a significant number of patients who could receive pre-hospital fibrinolysis within 2 hours after symptom onset.

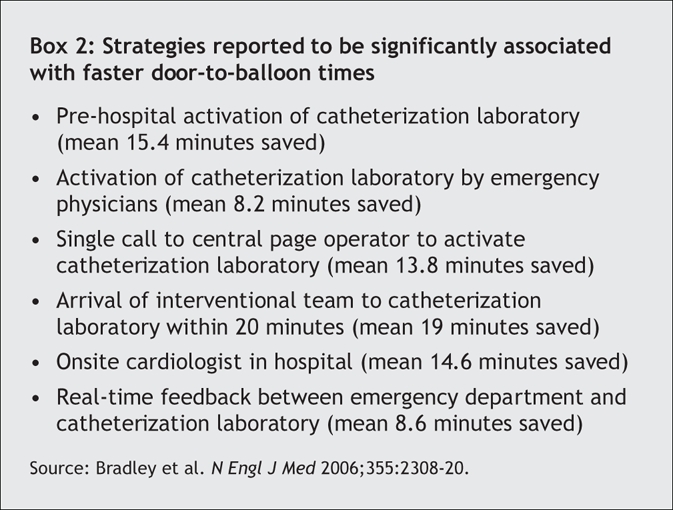

Overall, the Calgary cardiac team's collaboration with the EMS providers appeared to improve the delivery of percutaneous coronary intervention. Complimentary evidence in a recent large survey of 365 hospitals in the United States demonstrated 6 strategies that were significantly associated with faster door-to-balloon times (Box 2).9

Box 2.

Regardless of what reperfusion strategy is chosen in a community, collaboration with local EMS providers will reduce all time intervals between symptom onset and advanced cardiac care. The chain of survival starts with the recognition of concern from people with sustained chest pain. People with such symptoms should call 911 to ensure rapid cardiac care. Next, emergency departments should recognize and integrate basic, intermediate and advanced paramedic roles into their care plan for ST-segment elevation MI. Cardiologists and internists should continue to collaborate with emergency departments and pre-hospital EMS providers to ensure optimal patient outcomes. True success, such as the Calgary experience, requires system integration and ongoing monitoring of care processes.

@ See related article page 1833

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Andrew Travers has received speaker fees from Roche Pharmaceuticals to present information on Emergency Medical Services and care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction at national scientific meetings of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians and the Canadian Cardiovascular Society, and during site visits to various communities in Canada interested in pre-hospital care for ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction.

Correspondence to: Dr. Andrew Travers, Provincial Medical Director, Emergency Health Services, 200–239 Brownlow Ave., Dartmouth NS B3B 2B2; traverah@gov.ns.ca

REFERENCES

- 1.Armstrong PW, Bogaty P, Buller CE, et al. The 2004 ACC/AHA guidelines: a perspective and adaptation for Canada by the Canadian Cardiovascular Society Working Group. Can J Cardiol 2004;20:1075-9. [PubMed]

- 2.Van de Werf F, Ardissino D, Betriu A, et al. Task Force on the Management of Acute Myocardial Infarction of the European Society of Cardiology. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J 2003;24:28-66. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Antman EM, Anbe DT, Armstron PW, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for the management of patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction. A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee to Revise the 1999 Guidelines for the Management of Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction). J Am Coll Cardiol 2004;44:E1-E211. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.De Villiers JS, Anderson T, McMeekin JD, et al. Expedited transfer for primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a program evaluation. CMAJ 2007;176:1833-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Morrison LJ, Brooks S, Sawadsky B, et al. Prehospital 12-lead electrocardiography impact on acute myocardial infarction treatment times and mortality: a systematic review. Acad Emerg Med 2005;13:84-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Armstrong PW; WEST Steering Committee. A comparison of pharmacologic therapy with/without timely coronary intervention vs. primary percutaneous intervention early after ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the WEST (Which Early ST-elevation myocardial infarction Therapy) study. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1530-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Steg PG, Bonnefoy E, Chabaud S, et al. Impact of time to treatment on morbidity after prehospital fibrinolysis or primary angioplasty. Circulation 2003;108:2851-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Bjorklund E, Stenestrand U, Linback J, et al. Pre-hospital thrombolysis delivered by paramedics is associated with a reduced time delay and morbidity in ambulance-transported real-life patients with ST elevation myocardial infarction. Eur Heart J 2006;27:1146-52. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Bradley EH, Herrin J, Wang Y, et al. Strategies for reducing the door-to-balloon time in acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2006;355:2308-20. [DOI] [PubMed]