Abstract

The DNA sequence flanking a tet(W) gene in an oral Rothia sp. was determined. The gene was linked to two different transposases, and these were flanked by two almost identical mef (macrolide efflux) genes. This structure was found in 4 out of 20 tet(W)-containing oral bacteria investigated.

In the oral cavity, tetracycline resistance is most commonly mediated by tet(M) and is often associated with Tn916 or closely related elements (5, 7). The second most commonly isolated tetracycline resistance gene from the oral cavity is tet(W) (12). Originally found on a large conjugative chromosomal element, TnB1230, in a rumen commensal (4), the tet(W) gene has since been found in other species of bacteria, and it is not associated with a TnB1230-like element in these organisms (2, 3, 10, 11). However, it has been found in a mobile element called ATE-1 in Arcanobacterium pyogenes which is not related to TnB1230 (2). In order to understand the genetic basis for tetracycline resistance in bacteria from the oral cavity, the tet(W) gene was cloned from a previously isolated Rothia sp. (12), a species in which tet(W) is commonly found. Rothia spp. are gram-positive, facultatively anaerobic, nonsporeforming, nonmotile bacteria which are usually commensal, although they have occasionally been shown to cause disease (8).

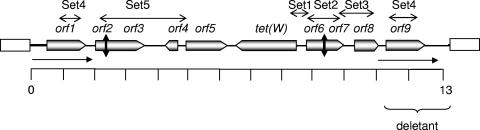

The methods for sampling, culture, and detection of tet(W)-containing strains have been described previously (12). Plasmid DNA was isolated using QIAprep miniprep and midiprep kits by following the supplier's protocol (QIAGEN, Crawley, United Kingdom). When required, cultures were supplemented with tetracycline (5 μg/ml). Genomic DNA was prepared from Rothia sp. strain T40.1 using a Puregene kit (Gentra, Flowgen, Nottingham, United Kingdom). Genomic DNA was partially digested with MboI (NEB, Hitchin, United Kingdom), and fragments between 4 and 15 kb were cut from an agarose gel and purified using a QIAquick gel extraction kit (QIAGEN). These fragments were ligated into BamHI-digested and dephosphorylated pUC18. Transformants containing tet(W) were selected on Luria-Bertani (9) agar plates containing ampicillin (50 μg/ml) and tetracycline (5 μg/ml). Plasmid DNA was isolated and digested with HindIII and EcoRI to liberate the inserts. One plasmid carrying the cloned tetracycline resistance gene and designated pPPMW was selected for further study. Approximately 7 kb of the 12.6-kb insert of pPPMW was sequenced by Lark Technology Inc. (Takeley, United Kingdom); the remaining sequence was obtained in-house using Big Dye terminator ready reaction mix version 3.1 and an ABI 310 genetic analyzer. Primers were designed using Primer3 software (http://frodo.wi.mit.edu/cgi-bin/primer3/primer3_www.cgi). Sequencing was performed on both strands and was analyzed using BLAST software (1). Bacterial identification was carried out as described previously (6, 12). The pPPMW insert (accession number EF177463) contained nine potential open reading frames (ORFs) (Fig. 1 and Table 1).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram of the deduced genetic organization of the 13-kb insert contained in pPPMW and the deletion derivative (pPPMW-1) after the spontaneous loss of tet(W). The predicted direction of the transcription of the genes is shown by the direction of the arrowed boxes. The vertical double-headed arrows represent disruption points of the ORFs. The ORFs (orf2 and orf3) coding for the ATPase are disrupted by the insertion of 34 extra nucleotides, and there is a point mutation in IS256 (orf6 and orf7) leading to the introduction of a stop codon. The single-headed horizontal arrows represent the identical sequences present in the deletion derivative and in the right end of the 13-kb insert (the sequences are 100% identical at the nucleotide level), and these sequences are repeated in the left end of the 13-kb insert (they are 99% identical at the nucleotide level). A series of primers were designed to amplify the regions between tet(W) and IS256 (Set1), IS256 (Set2), IS256 and downstream orf8 (Set3), mef (Set4), and ATPases and IS30 (Set5). The regions corresponding to the resulting amplicons are indicated by the horizontal double-headed arrows.

TABLE 1.

Closest relatives to orf genes flanking tet(W) of a Rothia sp.

| ORF genea | Length of predicted protein (aa) | G+C content (%) | Closest relative | Source organism(s) | Predicted protein(s) | % Identity | E value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| orf1 | 413 | 58 | mef | Streptococcus spp. | Macrolide-efflux protein | 42 | 1e-75 |

| orf2 | 74 | 51 | ATPase | Streptococcus spp. | ATPase components of ABC transporters | 68 | 2e-14 |

| orf3 | 403 | 56 | ATPase | Streptococcus spp. | ATPase components of ABC transporters | 60 | 1e-137 |

| orf4 | 97 | 62 | 3′-end of asparate/ornithine carbamoyltransferase | Enterococcus/Lactococcus spp. | Aspartate/ornithine binding domain | 62 | 2e-15 |

| orf5 | 403 | 74 | IS30 transposase | Streptococcus spp. | Putative family of transposase | 30 | 1e-34 |

| tet(W) | 524 | 53 | tet(W) | Butyrivibrio fibrisolvens | Tetracycline resistance protein | 97 | 0.0 |

| orf6 | 224 | 62 | IS256 transposase | Mycobacterium avium | Putative family of transposase | 83 | 2e-91 |

| orf7 | 148 | 61 | IS256 transposase | Mycobacterium avium | Putative family of transposase | 78 | 2e-57 |

| orf8 | 204 | 58 | Putative protein | Burkholderia ambifaria | Putative protein | 30 | >5 |

| orf9 | 428 | 58 | mef | Streptococcus spp. | Macrolide-efflux protein | 42 | 1e-86 |

The orf2 and orf3 genes and the orf6 and orf7 genes are likely to be derived from the same genes that are split by the introduction of stop codons.

PCR primers were designed to amplify regions flanking the Rothia sp. strain T40.1 tet(W) gene. The binding sites of the primers are shown in Fig. 1. The sequences of the primers and the sizes of the amplicons are shown in Table 2. For each PCR, the conditions were as follows: 35 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 64°C, and 3 min at 72°C, with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. A total of 20 oral isolates, previously shown by PCR to contain tet(W) (12), were tested. The isolates were divided into three groups (Table 3). Group 1 contained four isolates (all from different human subjects) that had a genetic structure surrounding the tet(W) gene similar to that of Rothia sp. strain T40.1, and group 2 contained eight isolates (from a total of seven human subjects) that had partial homology to Rothia sp. strain T40.1. Group 3 contained eight isolates (all from different subjects) that did not produce any PCR products with the primer sets used, although two out of these eight isolates contained a mef gene and produced a PCR product with primer set 4 (Table 3, group 3).

TABLE 2.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Primer sequence | Size of amplicon (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Set1A | 5′-CTGTGCCACTGGAAGGAAGT-3′ | 806 | This study |

| Set1B | 5′-CGGTAGCGATACCCGTTG-3′ | ||

| Set2A | 5′-CAGTGGGGTCAACAAGATCC-3′ | 1,078 | This study |

| Set2B | 5′-AGTGGGGGTTCCTCCTGTT-3′ | ||

| Set3A | 5′-CGCTAATCTCATGTCCGTCA-3′ | 1,498 | This study |

| Set3B | 5′-GAAATGGCGTGCAGAAAAAC-3′ | ||

| Set4A | 5′-TCTGTTCTGCTGTGCCATTC-3′ | 1,250 | This study |

| Set4B | 5′-GCTATTGAATCTGCCCGGTA-3′ | ||

| Set5A | 5′-CAACGAGTATGCAGGTCGATT-3′ | 2,161 | This study |

| Set5B | 5′-GCTCCAGCATCCTCTGGAC-3′ |

TABLE 3.

Study of the genetic support of tet(W) isolated from oral bacteria by PCR

| Group | tet(W) isolate | Other tet gene | Result of PCR with primera

|

Genus | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Set1 | Set2 | Set3 | Set4 | Set5 | ||||

| 1 | T29.1 | None | + | + | + | + | + | Rothia |

| T40.1 | None | + | + | + | + | + | Rothia | |

| T54.2 | None | + | +? | + | + | + | Rothia | |

| T59.3 | None | + | + | + | + | + | Streptococcus | |

| 2 | T22.3 | tet(M) | + | + | − | + | +? | Rothia |

| T56.4 | None | + | + | − | + | +? | Rothia | |

| T60.2 | tet(M) | + | + | − | + | + | Staphylococcus | |

| T60.9 | None | + | + | − | + | + | Actinomyces | |

| T44.5 | None | + | + | − | − | + | Lactobacillus | |

| T48.7 | None | + | + | − | − | + | Lactobacillus | |

| T43.7 | None | + | + | − | − | − | Actinomyces | |

| T51.1 | None | + | + | − | − | − | Lactobacillus | |

| 3 | T27.5 | tet(M) | − | − | − | − | − | Staphylococcus |

| T32.6 | tet(M) | − | − | − | − | − | Actinomyces | |

| T34.4 | tet(L) | − | − | − | − | − | Actinomyces | |

| T39.3 | None | − | − | − | − | − | Actinomyces | |

| T46.6 | None | − | − | − | − | − | Actinomyces | |

| T50.1 | None | − | − | − | + | − | Rothia | |

| T51.6 | None | − | − | − | + | − | Rothia | |

| T55.5 | None | − | − | − | − | − | Actinomyces | |

+, PCR product produced; −, PCR product not produced; +?, end sequencing showed that a specific amplicon was obtained with these isolates, but this amplicon was larger than that obtained with the positive control.

The 286-bp sequence upstream of the Rothia tet(W) gene has 90% identity to the equivalent region upstream of tet(W) in the ATE-1 element of Arcanobacterium pyogenes (2). There is no homology between regions downstream of the Rothia tet(W) gene to regions flanking other tet(W) genes. In these other tet(W) genes, the 92 bp downstream of the gene are conserved in all tet(W) genes sequenced (4).

The tet(W) gene cloned in Escherichia coli was unstable, being lost after overnight culture in the absence of tetracycline. Plasmids were prepared from five tetracycline-sensitive colonies and digested with HindIII and EcoRI, revealing that an 11-kb sequence had been deleted (results not shown). One of the deletion derivatives, pPPMW-1, was selected for further study. When the Rothia sp. strain (T40.1) was grown in the absence of tetracycline, no loss of tet(W) was observed after 21 passages, showing that the gene is stable in its original host.

In pPPMW, there is a directly repeated sequence of 2,129 bp (orf1 and orf9, which are nearly identical mef genes) that flanks the region containing the tet(W) gene (Fig. 1). DNA sequencing of the deleted derivative (pPPMW-1) shows that the first repeat is deleted along with all the DNA between the two direct repeats [i.e., orf1 to orf8 and tet(W)], leaving behind one copy of the repeat containing the second mef gene, orf9 (Fig. 1).

Rothia sp. strain T40.1 was mated with Enterococcus faecalis JH2-2 to determine if tet(W) is transferable. No transconjugants were obtained, indicating a transfer frequency of less than 10−9 per donor. However, further work is required to prove unequivocally that tet(W) cannot be transferred from this strain.

In conclusion, we have shown that the tet(W) gene is contained within a number of different genetic supports in oral bacteria. Furthermore, in Rothia sp. strain T40.1, the gene is linked to insertion sequences and flanked by directly repeated mef genes. Recombination between these direct repeats presumably contributes to the observed instability of the tet(W) gene in E. coli.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by project grant G99000875 from the Medical Research Council of the United Kingdom and by the BBSRC (D15925).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 19 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Altschul, S. F., W. Gish, W. Miller, E. W. Myers, and D. J. Lipman. 1990. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 215:403-410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Billington, S. J., and B. H. Jost. 2006. Multiple genetic elements carry the tetracycline resistance gene tet(W) in the animal pathogen Arcanobacterium pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:3580-3587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Billington, S. J., J. G. Singer, and B. H. Jost. 2002. Widespread distribution of a Tet W determinant among tetracycline-resistant isolates of the animal pathogen Arcanobacterium pyogenes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 46:1281-1287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kazimierczak, K. A., H. J. Flint, and K. P. Scott. 2006. Comparative analysis of sequences flanking tet(W) resistance genes in multiple species of gut bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 50:2632-2639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lancaster, H., A. P. Roberts, R. Bedi, M. Wilson, and P. Mullany. 2004. Characterization of Tn916S, a Tn916-like element containing the tetracycline resistance determinant tet(S). J. Bacteriol. 186:4395-4398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maidak, B. L., J. R. Cole, T. G. Lilburn, C. T. Parker, P. R. Saxman, J. M. Stredwick, G. M. Garrity, G. J. Olsen, S. Pramanik, T. M. Schmidt, and J. M. Tiedje. 2000. The RDP (Ribosomal Database Project) continues. Nucleic Acids Res. 28:173-174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts, A. P., G. Cheah, D. Ready, J. Pratten, M. Wilson, and P. Mullany. 2001. Transfer of Tn916-like elements in microcosm dental plaques. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45:2943-2946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sadhu A, R. Loewenstein, and S. A. Klotz. 2005. Rothia dentocariosa endocarditis complicated by multiple cerebellar hemorrhages. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 53:239-240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 10.Stanton, T. B., and S. B. Humphrey. 2003. Isolation of tetracycline-resistant Megasphaera elsdenii strains with novel mosaic gene combinations of tet(O) and tet(W) from swine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:3874-3882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stanton, T. B., J. S. McDowall, and M. A. Rasmussen. 2004. Diverse tetracycline resistance genotypes of Megasphaera elsdenii strains selectively cultured from swine feces. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:3754-3757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Villedieu, A., M. L. Diaz-Torres, N. Hunt, R. McNab, D. A. Spratt, M. Wilson, and P. Mullany. 2003. Prevalence of tetracycline resistance genes in oral bacteria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:878-882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]