Abstract

Background—The oesophageal epithelium is exposed routinely to noxious agents in the environment, including gastric acid, thermal stress, and chemical toxins. These epithelial cells have presumably evolved effective protective mechanisms to withstand tissue damage and repair injured cells. Heat shock protein or stress protein responses play a central role in protecting distinct cell types from different types of injury. Aim—To determine (i) whether biochemical analysis of stress protein responses in pinch biopsy specimens from human oesophageal epithelium is feasible; (ii) whether undue stresses are imposed on cells by the act of sample collection, thus precluding analysis of stress responses; and (iii) if amenable to experimentation, the type of heat shock protein (Hsp) response that operates in the human oesophageal epithelium. Methods—Tissue from the human oesophagus comprised predominantly of squamous epithelium was acquired within two hours of biopsy and subjected to an in vitro heat shock. Soluble tissue cell lysates derived from untreated or heat shocked samples were examined using denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis for changes in: (i) the pattern of general protein synthesis by labelling epithelial cells with 35S-methionine and (ii) the levels of soluble Hsp70 protein and related isoforms using immunochemical protein blots. Results—A single pinch biopsy specimen is sufficient to extract and analyse specific sets of polypeptides in the oesophageal epithelium. After ex vivo heat shock, a classic inhibition of general protein synthesis is observed and correlates with the increased synthesis of two major proteins of molecular weight of 60 and 70 kDa. Notably, cells from unheated controls exhibit a "stressed" biochemical state 22 hours after incubation at 37°C, as shown by inhibition of general protein synthesis and increased synthesis of the 70 kDa protein. These data indicate that only freshly acquired specimens are suitable for studying stress responses ex vivo. No evidence was found that the two heat induced polypeptides are previously identified Hsp70 isoforms. In fact, heat shock results in a reduction in the steady state concentrations of Hsp70 protein in the oesophageal epithelium. Conclusion—Systematic and highly controlled studies on protein biochemistry are possible on epithelial biopsy specimens from the human oesophagus. These technical innovations have permitted the discovery of a novel heat shock response operating in the oesophageal epithelium. Notably, two polypeptides were synthesised after heat shock that seem to differ from Hsp70 protein. In addition, the striking reduction in steady state concentrations of Hsp70 protein after heat shock suggests that oesophageal epithelium has evolved an atypical biochemical response to thermal stress.

Keywords: oesophagus; heat shock; Hsp70; hyperthermia; stress responses; cancer

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (171.7 KB).

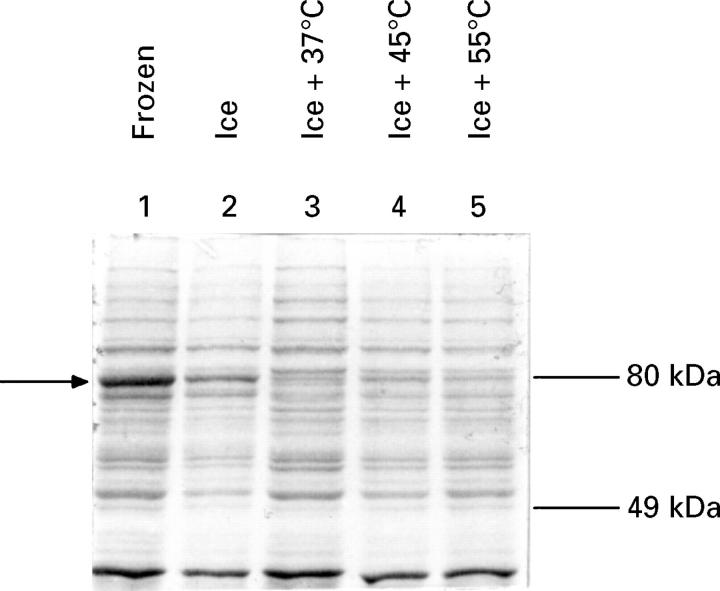

Figure 1 .

: Ex vivo steady state protein concentrations derived from tissue biopsy samples. Soluble protein (10 µg) derived from tissue lysates was applied to a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and total protein was detected by staining with Commassie blue. Before lysis, the tissue samples were treated as follows: lane 1, immediately frozen; lane 2, incubated in media at 0°C before freezing; lanes 3-5, transfered from 0°C to media at 37°C and then immediately incubated for 20 minutes at either 37°C (lane 3), 45°C (lane 4), or 55°C (lane 5). Then, samples were incubated at 37°C for four hours and were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen. The arrow shows the migration of a predominant polypeptide whose concentrations were dramatically reduced ex vivo.

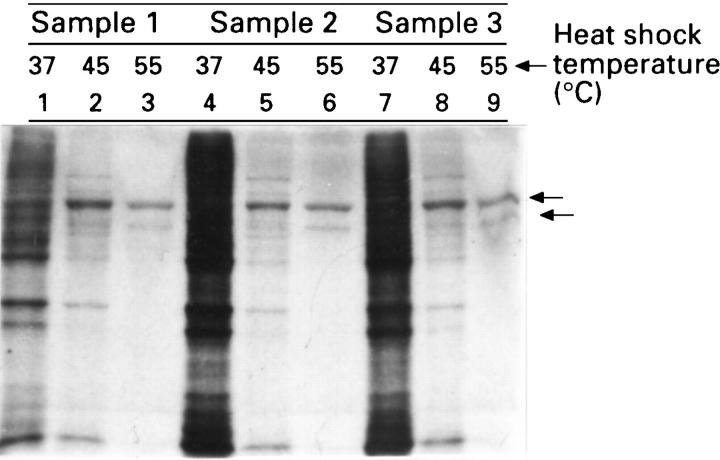

Figure 2 .

: Protein synthesis in tissue biopsy samples after an in vitro heat shock at different temperatures. Samples from three representative patients (samples 1-3) were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C (lanes 1, 4, and 7), 45°C (lanes 2, 5, and 8), or 55°C (lanes 3, 6, and 9), and then after four hours of equilibration at 37°C, the samples were incubated in fresh media containing 35S-methionine for an additional 45 minutes at 37°C. Radiolabelled protein derived from cell lysates was visualised using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorography. The arrows show the migration of the two major polypeptides synthesised after heat shock.

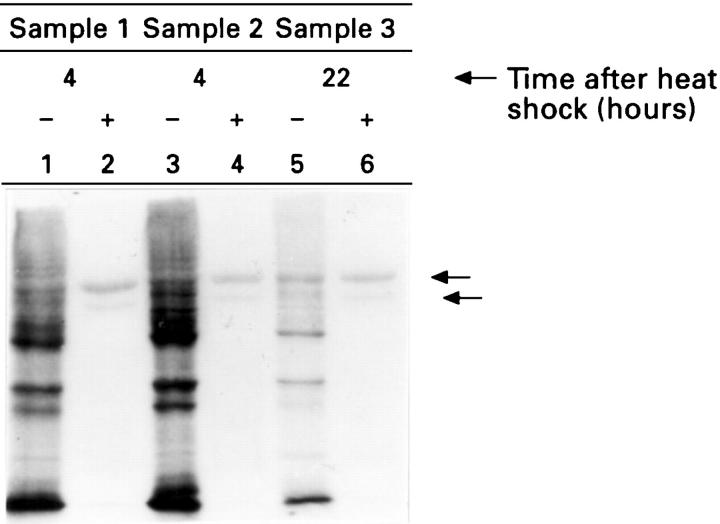

Figure 3 .

: Prolonged incubation of tissue biopsy specimens induces a stress protein response in the absence of heat shock. Samples from three representative patients (samples 1-3) were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C (lanes 1, 3, and 5) or 55°C (lanes 2, 4, and 6), and then after four hours (lanes 1-4) or 22 hours (lanes 5 and 6) of equilibration at 37°C, the samples were incubated in fresh media containing 35S-methionine for an additional 45 minutes at 37°C. Radiolabelled protein derived from cell lysates was visualised using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorography. The arrows show the migration of the two major polypeptides synthesised after heat shock.

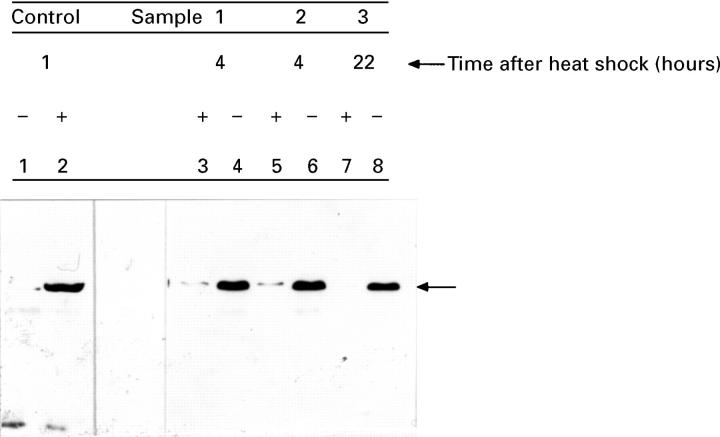

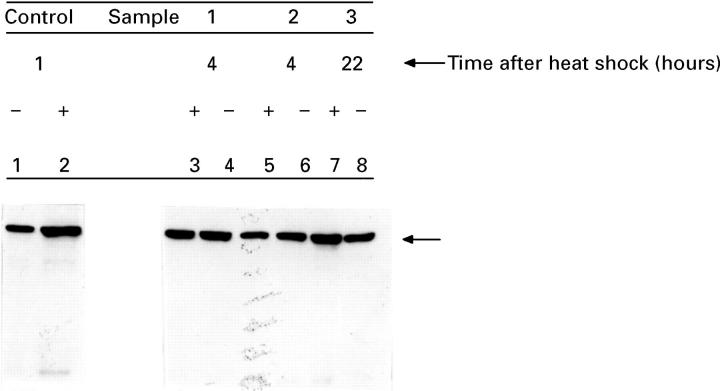

Figure 4 .

: Hsp70 protein concentrations decline after heat shock. Biopsy samples from three representative patients (samples 1-3) were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C (lanes 4, 6, and 8) or 55°C (lanes 3, 5, and 7), and then after four hours (lanes 3-6) or 22 hours (lanes 7 and 8) of equilibration at 37°C, the samples were incubated in fresh media containing 35S-methionine for an additional 45 minutes at 37°C. Hsp70 protein derived from soluble cell lysates (10 µg) was visualised using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody specific for Hsp70 protein. As a control, the concentrations of Hsp70 protein were measured in soluble lysates from normal (10 µg; lane 1) or heat shocked lung (lane 2; one hour after a mild hyperthermic induction in male Wistar rats). The arrows show the migration of Hsp70 protein.

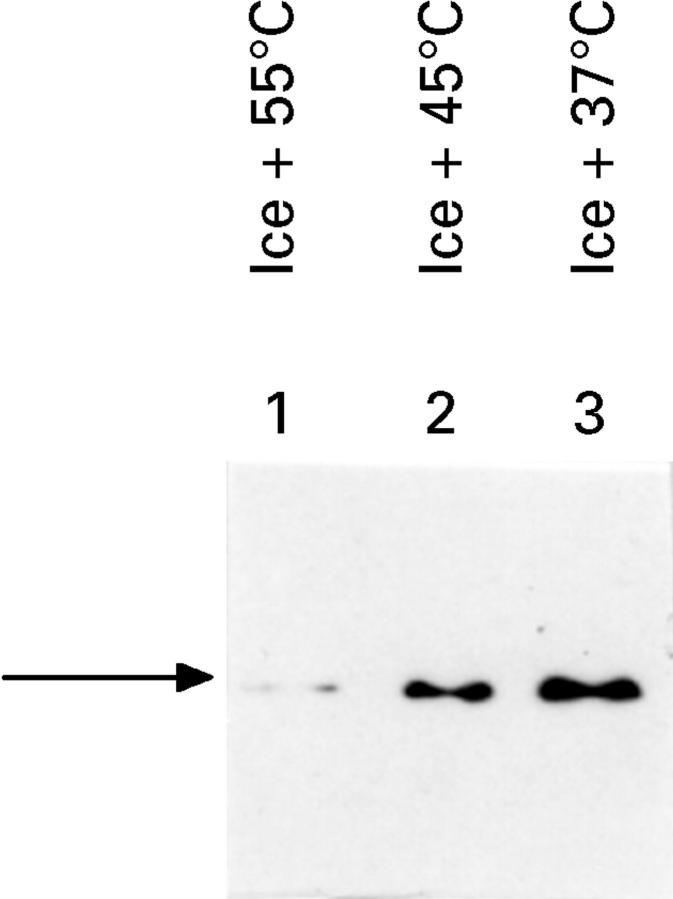

Figure 5 .

: Progressive decrease in Hsp70 protein concentrations with increasing thermal stress. Tissue biopsy samples were treated as follows: the cells were transfered from 0°C to media at 37°C and then incubated for 20 minutes at either 37°C (lane 3), 45°C (lane 2), or 55°C (lane 1). Then, samples were incubated at 37°C for four hours and were frozen in liquid nitrogen. Soluble protein (10 µg) derived from tissue lysates was applied to a 10% SDS-polyacrylamide gel and Hsp70 protein concentrations were quantified using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody specific for Hsp70 protein. The arrow shows the migration of Hsp70 protein.

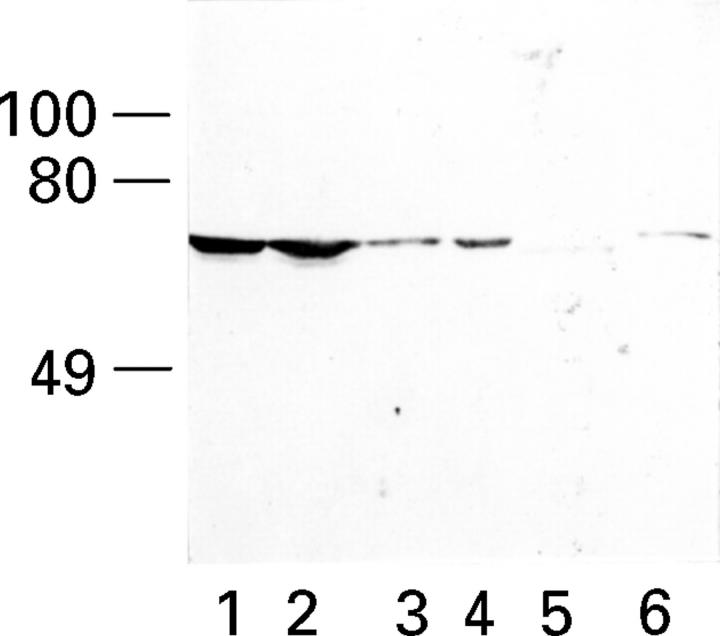

Figure 6 .

: Characterisation of a novel monoclonal antibody to Hsp70 protein isoforms. Protein immunoblots using a novel monoclonal antibody generated to Hsp70 protein (MB-H1) were performed with purified Hsp70 (lane 5), purified Hsc70 (lane 6) and the Hsp70/Hsc70 isoforms in four distinct tumour cell lines (lanes 1-4; BT549 (breast cancer); HS913T (fibrosarcoma); SK-UT-1 (leiomyosarcoma); and MCF7 (breast cancer), respectively).

Figure 7 .

: Hsc70 protein concentrations remain constant after heat shock. Biopsy samples from three representative patients (samples 1-3) were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C (lanes 4, 6, and 8) or 55°C (lanes 3, 5, and 7), then after four hours (lanes 3-6) or 22 hours (lanes 7 and 8) of equilibration at 37°C, the samples were incubated in fresh media containing 35S-methionine for an additional 45 minutes at 37°C. Hsc70 protein and related isoforms derived from soluble cell lysates were visualised using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with monoclonal antibody MB-H1. As a control, the concentrations of Hsp70 protein were determined in soluble lysates from normal (10 µg; lane 1) or heat shocked lung (lane 2; one hour after a mild hyperthermic induction in male Wistar rats). The arrows show the migration of Hsc70 protein and isoforms.

Figure 8 .

: The effects of ethanol and acid exposure on the heat shock protein response. Biopsy samples were incubated for 20 minutes at 37°C in normal media (lane 3), low pH media (lane 2), or 4% ethanol (lane 1). After four hours of equilibration at 37°C in fresh media, the samples were incubated in media containing 35S-methionine for an additional 45 minutes at 37°C. Left panel: radiolabelled protein derived from cell lysates was visualised using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and fluorography. Right panel: Hsp70 protein derived from cell lysates was visualised using SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and immunoblotting with a monoclonal antibody specific for Hsp70. The arrow shows the migration of Hsp70 protein.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Blake M. J., Buckley A. R., Zhang M., Buckley D. J., Lavoi K. P. A novel heat shock response in prolactin-dependent Nb2 node lymphoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1995 Dec 8;270(49):29614–29620. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.49.29614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chatson G., Perdrizet G., Anderson C., Pleau M., Berman M., Schweizer R. Heat shock protects kidneys against warm ischemic injury. Curr Surg. 1990 Nov-Dec;47(6):420–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie R. W., White F. P. Trauma-induced protein in rat tissues: a physiological role for a "heat shock" protein? Science. 1981 Oct 2;214(4516):72–73. doi: 10.1126/science.7280681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong U. W., Day N. E., Mounier-Kuhn P. L., Haguenauer J. P. The relationship between the ingestion of hot coffee and intraoesophageal temperature. Gut. 1972 Jan;13(1):24–30. doi: 10.1136/gut.13.1.24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dix D. J., Allen J. W., Collins B. W., Mori C., Nakamura N., Poorman-Allen P., Goulding E. H., Eddy E. M. Targeted gene disruption of Hsp70-2 results in failed meiosis, germ cell apoptosis, and male infertility. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Apr 16;93(8):3264–3268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dooley C. P., Di Lorenzo C., Valenzuela J. E. Esophageal function in humans. Effects of bolus consistency and temperature. Dig Dis Sci. 1990 Feb;35(2):167–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01536758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galipeau P. C., Cowan D. S., Sanchez C. A., Barrett M. T., Emond M. J., Levine D. S., Rabinovitch P. S., Reid B. J. 17p (p53) allelic losses, 4N (G2/tetraploid) populations, and progression to aneuploidy in Barrett's esophagus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996 Jul 9;93(14):7081–7084. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.14.7081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick J. P., Hartl F. U. Molecular chaperone functions of heat-shock proteins. Annu Rev Biochem. 1993;62:349–384. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.002025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirakawa T., Rokutan K., Nikawa T., Kishi K. Geranylgeranylacetone induces heat shock proteins in cultured guinea pig gastric mucosal cells and rat gastric mucosa. Gastroenterology. 1996 Aug;111(2):345–357. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8690199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood D., Spiers E. M., Ross P. E., Anderson J. T., McCullough J. B., Murray F. E. Endocytosis of fluorescent microspheres by human oesophageal epithelial cells: comparison between normal and inflamed tissue. Gut. 1995 Nov;37(5):598–602. doi: 10.1136/gut.37.5.598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaskiewicz K., Louw J., Anichkov N. Barrett's oesophagus: mucin composition, neuroendocrine cells, p53 protein, cellular proliferation and differentiation. Anticancer Res. 1994 Sep-Oct;14(5A):1907–1912. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karmazyn M., Mailer K., Currie R. W. Acquisition and decay of heat-shock-enhanced postischemic ventricular recovery. Am J Physiol. 1990 Aug;259(2 Pt 2):H424–H431. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1990.259.2.H424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Locke M., Noble E. G., Atkinson B. G. Exercising mammals synthesize stress proteins. Am J Physiol. 1990 Apr;258(4 Pt 1):C723–C729. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1990.258.4.C723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu X. P., Omar R. A., Chang W. W. Immunocytochemical expression of the 70 kD heat shock protein in ischaemic bowel disease. J Pathol. 1996 Aug;179(4):409–413. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199608)179:4<409::AID-PATH602>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez C. M., Sneed P. K., Li G. C., Mak J. Y., Phillips T. L. HSP 70 synthesis in clinical hyperthermia patients: preliminary results of a new technique. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1994 Jan 15;28(2):425–430. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(94)90066-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martins E. B., Chapman R. W., Marron K., Fleming K. A. Biliary expression of heat shock protein: a non-specific feature of chronic cholestatic liver diseases. J Clin Pathol. 1996 Jan;49(1):53–56. doi: 10.1136/jcp.49.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur S. K., Sistonen L., Brown I. R., Murphy S. P., Sarge K. D., Morimoto R. I. Deficient induction of human hsp70 heat shock gene transcription in Y79 retinoblastoma cells despite activation of heat shock factor 1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994 Aug 30;91(18):8695–8699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.18.8695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy J. L., Nations C. Activity of some dehydrogenase enzymes in mitochondria from Physarum polycephalum. Comp Biochem Physiol B. 1979;63(4):495–499. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(79)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehlen P., Schulze-Osthoff K., Arrigo A. P. Small stress proteins as novel regulators of apoptosis. Heat shock protein 27 blocks Fas/APO-1- and staurosporine-induced cell death. J Biol Chem. 1996 Jul 12;271(28):16510–16514. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.28.16510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minowada G., Welch W. J. Clinical implications of the stress response. J Clin Invest. 1995 Jan;95(1):3–12. doi: 10.1172/JCI117655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mivechi N. F., Giaccia A. J. Mitogen-activated protein kinase acts as a negative regulator of the heat shock response in NIH3T3 cells. Cancer Res. 1995 Dec 1;55(23):5512–5519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murtha-Riel P., Davies M. V., Scherer B. J., Choi S. Y., Hershey J. W., Kaufman R. J. Expression of a phosphorylation-resistant eukaryotic initiation factor 2 alpha-subunit mitigates heat shock inhibition of protein synthesis. J Biol Chem. 1993 Jun 15;268(17):12946–12951. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura K., Rokutan K., Marui N., Aoike A., Kawai K. Induction of heat shock proteins and their implication in protection against ethanol-induced damage in cultured guinea pig gastric mucosal cells. Gastroenterology. 1991 Jul;101(1):161–166. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90473-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nijhoff W. A., Peters W. H. Quantification of induction of rat oesophageal, gastric and pancreatic glutathione and glutathione S-transferases by dietary anticarcinogens. Carcinogenesis. 1994 Sep;15(9):1769–1772. doi: 10.1093/carcin/15.9.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdrizet G. A., Heffron T. G., Buckingham F. C., Salciunas P. J., Gaber A. O., Stuart F. P., Thistlethwaite J. R. Stress conditioning: a novel approach to organ preservation. Curr Surg. 1989 Jan-Feb;46(1):23–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polla B. S., Stubbe H., Kantengwa S., Maridonneau-Parini I., Jacquier-Sarlin M. R. Differential induction of stress proteins and functional effects of heat shock in human phagocytes. Inflammation. 1995 Jun;19(3):363–378. doi: 10.1007/BF01534393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel S., Reid B. J., Sanchez C. A., Blount P. L., Levine D. S., Neshat K., Haggitt R. C., Dean P. J., Thor K., Rabinovitch P. S. Evaluation of p53 protein expression in Barrett's esophagus by two-parameter flow cytometry. Gastroenterology. 1992 Apr;102(4 Pt 1):1220–1228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto Y., Kobori O. Role of reflux oesophagitis and acid in the development of columnar epithelium in the rat oesophagus. Br J Surg. 1993 Apr;80(4):467–470. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800800420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spechler S. J., Goyal R. K. The columnar-lined esophagus, intestinal metaplasia, and Norman Barrett. Gastroenterology. 1996 Feb;110(2):614–621. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.agast960614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobey N. A., Orlando R. C. Mechanisms of acid injury to rabbit esophageal epithelium. Role of basolateral cell membrane acidification. Gastroenterology. 1991 Nov;101(5):1220–1228. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90070-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobey N. A., Reddy S. P., Keku T. O., Cragoe E. J., Jr, Orlando R. C. Studies of pHi in rabbit esophageal basal and squamous epithelial cells in culture. Gastroenterology. 1992 Sep;103(3):830–839. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90014-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trautinger F., Kindås-Mügge I., Barlan B., Neuner P., Knobler R. M. 72-kD heat shock protein is a mediator of resistance to ultraviolet B light. J Invest Dermatol. 1995 Aug;105(2):160–162. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12317003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch W. J. Mammalian stress response: cell physiology, structure/function of stress proteins, and implications for medicine and disease. Physiol Rev. 1992 Oct;72(4):1063–1081. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1992.72.4.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler J. C., Bieschke E. T., Tower J. Muscle-specific expression of Drosophila hsp70 in response to aging and oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995 Oct 24;92(22):10408–10412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeargin J., Haas M. Elevated levels of wild-type p53 induced by radiolabeling of cells leads to apoptosis or sustained growth arrest. Curr Biol. 1995 Apr 1;5(4):423–431. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(95)00083-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]