Abstract

The value of salivary biomarkers for diagnostic and prognostic assessments has become increasingly well established in medicine, pharmacology, and dentistry. Certain salivary components mirror the neuro-endocrine status of the organism. Other saliva products are protein in nature, and can serve to reflect immune surveillance processes. The autonomic nervous system regulates the process of salivation, and the concentration of yet other salivary components, such as α-amylase, which provide a reliable outcome measure of the sympathetic response. Here, we discuss molecular technologies that have permitted giant steps in the utilization of salivary samples and micro-fluidics for the benefit of diagnostic medicine and dentistry, and their putative role in springing forward research in psychobiology.

Keywords: saliva, biomarker, physiology, psychobiology, diagnosis

Background

That invertebrates exhibit structures that produce a saliva-like substance demonstrates the critical importance of this physiological fluid throughout evolution. In higher vertebrates, including humans, parotideal, sublingual and submandibular salivary glands produce saliva, besides smaller glands spread over the oral cavity, including the tip of the tongue. Histologically, salivary glands consist of blind ducts surrounded by capillary vessels and embedded in connective tissue. Saliva obtains by filtering capillary blood through acinar cell membranes, thus preventing certain blood components from passing, including hormone-binding proteins, and making of saliva a fluid distinct from blood plasma or serum. Saliva is distinct from sputum, the mucus or phlegm expectorated from the respiratory tract and mixed with saliva.

Saliva is primarily water buffered (pH: 6.4–7.4) by its biochemical constituents: electrolytes, minerals, hormones (e.g., cortisol; diurnal peak: 13.8–48.9 nmol/l, compared to blood: 190–690 nmol/l), enzymes, immunoglobulins, cytokines (Figure 1), and other analytes. The physiological roles of saliva include moistening food to aid chewing and swallowing, initiating digestion through salivary enzymes (e.g., Sα-amylase, EC3.2.1.1; 11,900–305,000 U/I, compared to blood: < 220 U/l), and cleansing the mouth and teeth by washing away bacteria and food particles.

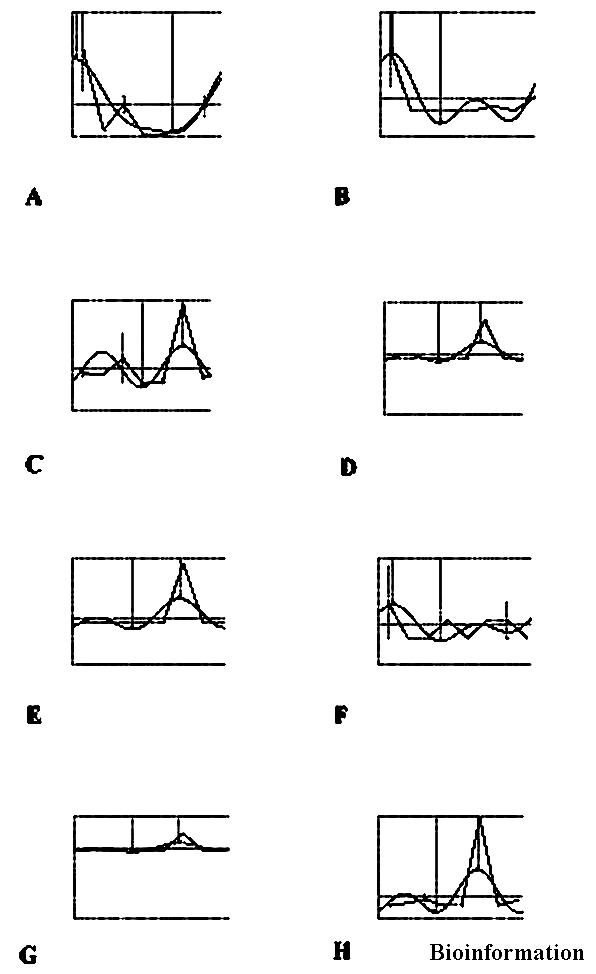

Figure 1.

Circadian fluxes of critical cytokines in human saliva. Whole saliva samples were obtained from a healthy 35-years old male at 2 h intervals. Samples were assayed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Overnight data samples were extrapolated statistically. Circadian flux cosinor analyses were performed as previously described elsewhere. Some of the data presented in this figure (i.e., IL-6) were published elsewhere [1] and are presented here for comparison purposes only. Panel A: IL-8, a cytokine responsible for immune cell migration; Panel B: IL-1β, a proinflammatory cytokine; Panel C: IL-6, a proinflammatory cytokine; Panel D: IL-2, a TH1 cytokine, T cell activation, proliferation & maturation; Panel E: γ-IFN, a TH1 cytokine, T cell activation, proliferation & maturation; Panel F: IL-10, a regulatory cytokine that blunts γ-IFN and favors B cell maturation; Panel G: IL-12: a regulatory cytokine that blunts IL-10 and favors γ-IFN Panel H: IL-4, a TH2 cytokine, B cell maturation

The value of saliva as biological fluid for the detection of diagnostic and prognostic biomarkers has become increasingly well established. Sample collection is non-invasive, painless, and possible several times a day to provide accurate and reliable assessments of diurnal fluctuations of, for example, the unbound, biologically active, form of certain hormones and drugs. The autonomic nervous system regulates the process of salivation, and the concentration of certain salivary components (e.g., Sα-amylase) mirrors the sympathetic response. Other salivary constituents (e.g., cortisol; cytokines) reflect physiologic endocrine-immune regulation. Together, salivary cortisol and α-amylase can outline the neuro-endocrine status.

Yet other peptides in saliva manifest blood circulating level, and have diagnostic utility. For example, we have shown that salivary α-Amyloid protein, the main constituent of neuronal plaques, is on average 3.34 fold higher in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease (AD) compared to aged- and sex-matched normal subjects, although no significant correlation between plasma and salivary levels (r=0.489) was obtained. We also compared several pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-1α, IL-6, TNFα), TH1 cytokines (IL-2, α-IFN, IL-12) and TH2 cytokines (IL-4), as well as markers of apoptosis (FasL, Annexin V) in saliva and plasma samples from normal individuals. That our salivary samples were not contaminated with serum exudate due to oral ulcerations and the like was confirmed by the lack of correlation for any of the pro-inflammatory cytokines we tested. A significant correlation was detected between plasma and salivary concentrations of Annexin V (r=0.611, p<0.05), but not in FasL levels (r=-.217). Newer HIV/AIDS tests reliably detect salivary antibodies to HIV-1.

Analyzing nanoliter samples of saliva through molecular biology (i.e., microfluidics) have spawned powerful techniques for making salivary diagnostics possible. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) provides critical data to forensic investigations, and to molecular medicine since saliva contains putative genetic markers for a variety of genetic disorders, including AD, cystic fibrosis, breast cancer, childhood respiratory disease, gum and periodontal disease, or oral cancer.

Description

Molecular technologies have permitted giant steps in the utilization of salivary samples and microfluidics for improved diagnosis. For example, high-density oligonucleotide microarrays and qPCR analysis yielded thousands of salivary mRNAs, which provided potential biomarkers to identify populations of patients at high risk for oral and systemic diseases. The mRNA profiles in putatively normal saliva generated a reference database, the basis for the establishment of a novel clinical approach to salivary diagnostics, now termed Salivary Transcriptome Diagnostics (STD). [2]

The diagnostic value of STD was tested in patients with oral squamous cell carcinoma. RNA isolated from unstimulated saliva was amplified by two-round linear amplification (T7 RNA polymerase), and profiled for the human salivary transcriptome (Human Genome U133A microarrays). Statistical analysis differentiated the patterns of gene expression, and was validated by qPCR and by receiver-operating curve analysis. Close to 1,700 genes were obtained that showed a significant difference in saliva expression between cancer patients and control subjects. Seven cancer-related mRNA biomarkers were identified: IL8, IL1α, DUSP1, HA3, OAZ1, S100P, and SAT, which together yielded a robust diagnostic sensitivity and specificity greater than 90%. Taken together, the data show that salivary transcriptome profiling can be exploited as a reproducible tool for early cancer detection, putatively for other pathological conditions, and for normal health surveillance. [3]

The protein counterparts of salivary mRNAs often, but not in every instance (60-75%) co-exist in saliva. Therefore, new developments in the molecular characterization of salivary components use global profiling of human saliva proteomes and transcriptomes by mass spectrometry (MS) to supplement STD. Expectations are that the saliva transcriptome will increasingly provides insights into the boundary of the saliva proteome. [4]

The full characterization of the salivary proteome, and its underlying transcriptome, will eventually serve prognostic clinical sciences as well. We have discussed elsewhere the process of allostasis, the physiological events that mirror the organism’s adaptation and recovery from physical, physiological or psycho-cognitive stress. Considering the fact that the salivary components describe and characterize the physiological status, it is self-evident that the next generation of psychobiological research will entail the characterization of the salivary proteome and of its underlying transcriptome.

Case in point, the assessment of Sα-amylase is a more sensitive and more specific measurement than blood pressure or heart rate in healthy adult subjects. The stress response has two principal facets: the neuro-endocrine, which involves corticotropin-release hormone, activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and the secretion of cortisol into circulation. Cortisol is then filtered through the acinar cell membrane of the salivary glands, and is found in saliva in the free unbound form. Secondly, the stress response involves activation of the autonomic nervous system, release of catecholamines (e.g., plasma norepinephrine, pNE), and sympatho-mimetic manifestations, such as increase salivation, and increase secretion of Sα-amylase. Sα-amylase levels increase under a variety of physical (i.e., exercise, heat and cold) and psychological (i.e., written examinations) challenges, and are predictive of pNE levels. Salivary or plasma cortisol levels do not always correlate with Sα-amylase following stress, confirming that the two pathways are distinct and complementary. [5 ,6]

The Trier psycho-socio/cognitive situational stress (mental arithmetic task and free speech in front of an audience) is a useful paradigm, which permits comparative study of the psychobiology of stress. In a group of normal adult subjects, the Trier stress led to significant differences between the response and the resting states in Sα-amylase and cortisol levels, and in heart rate. [5] However, the Sα-amylase responses expressed as the area under the curve did not correlate with the general responses in pNE and cortisol. [6]

In an earlier study, saliva and blood samples were simultaneously collected from normal healthy men for assessment of pNE and Sα-amylase at regular intervals following a variety of stress paradigms. The regressions of Sα- amylase on pNE concentrations were significant for both physical and psycho-cognitive situational stressful challenges: physical exercise stress led to a 3-fold average rise in Sα- amylase, and a 5-fold average rise in pNE. The levels of Sα- amylase and pNE returned to normal by 30-45 min post-stress. The psycho-cognitive stress (written examination) also led to a parallel rise in Sα-amylase and pNE. Changes in plasma cortisol levels were not correlated with pNE or Sα-amylase. [7]

Changes in salivation often accompany the stress response, therefore it is important to establish whether changes in Sα- amylase levels truly mirror the physiological response to stress, or merely confound altered salivary flow. Increases in Sα- amylase proteome profile can be inhibited by the adrenergic blocker propranol, but α-adrenergic agonists stimulate levels Sα- amylase release without increasing salivary flow. This important observation suggests that the same stimuli that increase sympathetic arousal activate sympathetic input to the salivary glands, independently from salivary gland flow. Normal human subjects who underwent the Trier test were tested for both salivary flow and Sα-amylase levels. The data establish that stress-induced increases in Sα-amylase levels were correlated with increases of the proteomic profile of interest but not with flow rate. [8]

In a natural interpersonal stress environment (parents/guardians and adolescents reporting on adolescents' aggressive behavior) cortisol and Sα-amylase levels accounted for 7% of the variance in parent-reported adolescent aggression. At lower Sα-amylase levels, lower cortisol responses corresponded to higher aggression ratings, but at high Sα-amylase concentrations, the cortisol response was not related to aggression. These results underscore the reliability of salivary outcome measures, and the importance of multiple biomarkers in psycho-social research, such as psychobiological paradigms models of adolescent aggression. [9]

Optimism and positive emotional states also modify the salivary biomarker profile. Optimism vs. pessimism (revised Life Orientation Test), and positive vs. negative affectivity (Chinese Affect Scale) were compared in an experimental setting, and the diurnal rhythm of salivary cortisol monitored in a group of 80 Hong Kong Chinese over 24 h on two consecutive days. The data showed striking statistical relationships in that participants with higher optimism scores exhibited lower AM cortisol secretion, when the effect of pessimism and mood were controlled. The outcome was greater among men, compared to women whose levels of AM cortisol were generally higher than men. The Optimism effect was not observed during the descending period of the cortisol diurnal flux (i.e., PM). Generalized positive affect was correlated with lower salivary cortisol levels in PM, when the effects of negative affect and mood states were controlled, but not during the ascending limb of the cortisol diurnal curve (i.e., AM). [10] In a separate study, positive mood with respect to personal relevance of daily activities in relation to self-set work and family goals were shown to be correlated with decreased secretion of salivary cortisol. The relationship between the goal relevance of daily activities and cortisol was shown statistically to be partially mediated by affect quality. [11] Taken together, these data suggest that positive psychological stimuli alter salivary biomarkers as well as stressful stimuli, and that salivary levels of cortisol may provide correlates of psychological well-being. The extent to which these observations relate to the salivary proteomic profile (e.g., α-amylase) remains to be established.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Drs. A. Angeli, M. Fiala and S. Harper for significant contributions during this work. The authors acknowledge funding from NIH Health (AI 07126; CA16042, DA07683, DA10442), the Alzheimer's Association, and the UCLA School of Dentistry.

Footnotes

Citation:Chiappelli et al., Bioinformation 1(8): 331-334 (2006)

References

- 1.Chiappelli F, et al. Allostasis in HIV Infection and AIDS In Neuro-AIDS. Nova Science Publisher Inc; 2006. p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li Y, et al. J Dental Res. 2004;83:199. doi: 10.1177/154405910408300303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:8130. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hu S, et al. J Dental Res. 2006;85:129. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nater UM, et al. Int J Psychophysiol. 2005;55:333. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2004.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nater UM, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2006;31:49. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterton RT. Clin Physiol. 1996;16:433. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-097x.1996.tb00731.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rohleder N, et al. Psychophysiol. 2006;43:645. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2006.00457.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gordis EB, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinol. 2006;31:976. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lai JC, et al. Br J Health Psychol. 2005;10:467. doi: 10.1348/135910705X26083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoppmann CA, Klumb PL. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:887. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000238232.46870.f1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]