Abstract

Access to the complete human genome sequence as well as to the complete sequences of pathogenic organisms provides information that can result in an avalanche of therapeutic targets. Structure-based design is one of the first techniques to be used in drug design. Structure based design refers specifically to finding and complementing the 3D structure (binding and/or active site) of a target molecule such as a receptor protein. The aim of this review is to give an outline of studies in the field of structure based drug design that has helped in the discovery process of new drugs. The emphasis will be on comparative/homology modeling.

Keywords: drug targets, protein modeling, ligands, design

Background

Discussion of the use of structural biology in drug discovery began over 35 years ago, with the advent of knowledge of the 3D structures of globins, enzymes and polypeptide hormones. Early ideas in circulation were the use of 3D structures to guide the synthesis of ligands of haemoglobin to decrease sickling or to improve storage of blood [1], the chemical modification of insulins to increase half-lives in circulation [2] and the design of inhibitors of serine proteases to control blood clotting. [3] An early and bold venture was the UK Wellcome Foundation programme focussing on haemoglobin structures established in 1975. [4] However, X-ray crystallography was expensive and time consuming. It was not feasible to bring this technique ‘in-house’ into industrial laboratories, and initially the pharmaceutical industry did not embrace it with any real enthusiasm. In time, knowledge of the 3D structures of target proteins found its way into thinking about drug design. Although, in the early days, structures of the relevant drug targets were usually not available directly from X-ray crystallography, comparative models based on homologues began to be exploited in lead optimization in the 1980s. [5] An example was the use of aspartic protease structures to model renin, a target for antihypertensives. [6] It was recognized that 3D structures were useful in defining topographies of the complementary surfaces of ligands and their protein targets, and could be exploited to optimize potency and selectivity. [7] Eventually, crystal structures of real drug targets became available; AIDS drugs, such as Agenerase and Viracept, were developed using the crystal structure of HIV protease [8] and the flu drug Relenza was designed using the crystal structure of neuraminidase. [9] There are now several drugs on the market that originated from this structure-based design approach; [10] list >40 compounds that have been discovered with the aid of structure-guided methods and that have entered clinical trials. The structure-based design methods used to optimize these leads into drugs are now often applied much earlier in the drug discovery process. Protein structure is used in target identification and selection (the assessment of the ‘druggability’ or tractability of a target), in the identification of hits by virtual screening and in the screening of fragments. Additionally, the key role of structural biology during lead optimization to engineer increased affinity and selectivity into leads remains as important as ever.

Description

Common drug targets

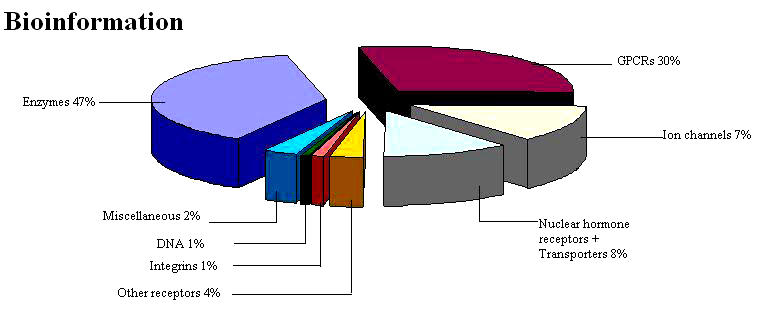

The introduction of genomics, proteomics and metabolomics has paved the way for biology-driven process, leading to plethora of drug targets. The list of potential drug targets encoded in a genome includes most natural choice of virulent genes and species-specific genes. Other options include targeting RNA, enzymes of the intermediary metabolism, systems for DNA replication, translation apparatus or repair and membrane proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Biochemical classes of drug targets

Species-specific genes as drug targets

Comparative analysis of the complete genome sequences of bacterial pathogens available in the public databases offers the first insights into drug discovery approaches of the near future. [11] An interesting approach to the prediction of potential drug targets designated as the differential genome display has been proposed by Bork and co-workers. [12] This approach relies on the fact that genome of parasitic microorganisms are generally much smaller and code for fewer proteins than the genomes of free-living organisms. The genes that are present in the genome of a parasitic bacterium, but absent in a closely related genome of free living bacterium, are therefore likely to be important for pathogenecity and can be considered as potential drug targets. Exhaustive comparison of H.influenzae and E.coli gene products identified 40 H.influenzae genes that have been exclusively found in pathogens and thus constitute potential drug targets.

Nucleic acid as drug targets

Nucleic acids are the repository of genetic information. DNA itself has been shown to be the receptor for many drugs used in cancer and other diseases. These work through a variety of mechanisms including chemical modification and cross linking of DNA (cisplatin) or cleavage of the DNA (bleomycin). Much work either by intercalation of a polyaromatic ring system into the double stranded helix (actinomycin D, ethidium) or by binding to the major and minor grooves of DNA (e.g., netropsin) (Figure 2) [13] has been reported. DNA has been shown to be the target for chemotherapy with efforts to design sequence-specific reagents for gene therapy.

Figure 2.

Netropsin molecule. The narrowness of the groove forces the netropsin molecule to sit symmetrically in the center, with its two pyrrole rings slightly non-coplanar so that each ring is parallel to the walls of its respective region of the groove [13]

RNA as drug target

Recent advances in the determination of RNA structure and function have led to new opportunities that will have a significant impact on the pharmaceutical industry. RNA, which, among other functions, serves as a messenger between DNA and proteins, was thought to be an entirely flexible molecule without significant structural complexity. However, recent studies have revealed a surprising intricacy in RNA structure. This observation unlocks opportunities for the pharmaceutical industry to target RNA with small molecules. Perhaps more importantly, drugs that bind to RNA might produce effects that cannot be achieved by drugs that bind to proteins. [14] Proof of the principle has already been provided by success of several classes of drugs obtained from natural sources that bind to RNA or RNA-protein complexes.

Membranes as drug targets

Membranes are significant structural elements, both in defining the boundaries of a cell as well as providing interior compartments within the cell associated with particular functions. Cell membranes themselves can also act as targets for molecular recognition. An understanding of the structural and dynamic functions of the membranes (e.g., plasma membranes and intercellular membranes) may add to a more rational design of drug molecules with improved permeation characteristics or specific membrane effects. Many general anesthetics are believed to work by their physical effects when dissolved in membranes. Several classes of antibiotics like gramicidin A, antifungals like alamethicin and toxins such as mellitin found in bee venoms have direct effects on planar lipid bilayers, causing transmembrane pores.

Proteins as drug targets

Proteins continue to assume significant attention from the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries as a valuable source of potential drug targets. [15] Proteins provide the critical link between genes and disease, and as such are the key to the understanding of basic biological processes including disease pathology, diagnosis, and treatment. Researchers have discovered many potential therapeutic targets, and there are currently more than 700 products in various phases of development. However, translating the study of proteins into validated drug targets poses substantial challenges. Genome sequences instruct cells on how and when to make proteins. The proteins in turn are the active players in the cell. Proteins form the machinery of cells, allow cells to communicate, and can control growth or death of an organism. Because of their role in cells, most of the drug targets are proteins. Drugs work by binding specifically to a protein. Extensive knowledge about the function of a protein can guide the selection of targets for pharmaceutical chemists. Studying the complex domain of 200,000-300,000 distinct and interactive proteins poses substantial challenges. Most target proteins for drug development participate in key regulatory steps in the human body or in an infectious organism. As such, they tend to be present in few copies only and often within specific cells. Their isolation and purification using traditional preparative biochemical means and in quantities required for routine assays has been a formidable challenge. This situation has been radically changed by the ability to clone and express proteins. Thus many key target proteins are now becoming available in sufficient amounts to make them amenable not only to biological assays but also to NMR studies in solution and to crystallization for X-ray analysis. The number of protein structures solved using X-ray or NMR has begun to rise sharply and more than 40,000 protein three-dimensional structures have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank [16] till date (December 2006). Various classes of proteins can be categorized as potential drug targets.

Small molecules such as drugs, insecticides or herbicides usually exert their effects by binding to protein targets. In the past, many of these molecules were found empirically with little or no knowledge of the mechanism of action involved. In many cases, the targets that are modified by these substances were identified in retrospect. Interestingly, the majority of drugs currently in use modulate either enzymes or receptors, most of them G-protein-coupled receptors.

a. Enzymes - The macromolecule responsible for the catalysis of biochemical reactions are an obvious target when a disease state is associated with production of a biologically active species. Enzymes are a classic target for therapeutic intervention and numerous well-studied examples exist.

Traditional medicinal chemistry enzyme targets include kinases, phosphodiesterases, proteases and phosphotases. Some of the examples of drug targeted against enzymes are listed in Table 1.

Table 1. Some enzymes as drug targets.

| Enzyme | Drug |

|---|---|

| Dihydrofolate reductase | Methotrexate |

| HIV-1 protease | Saquinavir, Indinavir |

| ACE | Captopril |

| Neuraminidase | Oseltamivir |

| Cyclin dependent Kinase(CDKs) | Flavopiridol |

| Cyclooxygenase | Diclofenac, Indomethacin |

| Thymidylate synthase | Tomudex |

| Guanine phosphoribosyltranseferase (GPRT) | Allopurinol |

| Inosine5'-monophosphate dehydrogense | Tiazopurin |

b. Receptor proteins - G-protein–coupled receptors are a super family of seven transmembrane spanning proteins that are activated by a wide range of extracellular ligands and are expressed in virtually all tissues. Signaling through these receptors regulates a wide variety of physiological processes such as neurotransmission, chemotaxis, inflammation, cell proliferation, cardiac and smooth muscle contraction as well as visual and chemosensory perception. In view of their widespread distribution and importance in health and disease, it is not surprising that GPCRs are the most successful class of target proteins for drug discovery research. [17]

The sequencing of human genome has led to the prediction of as many as 1000 GPCRs, of which 400 are non-chemosensory receptors and can therefore be considered as potential drug-targets. [18] It has been estimated that up to 50 % of all marketed drugs directly target this family of receptors [19], some of which are listed in Table 2.

Table 2. Some currently marketed drugs that target GPCRs.

| GPCR | Indication(s) | Drug(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Histamine | Allergies, ulcers | Cimetidine,Ranitidine,Terfenadine |

| β-adrenergic | Hypertension, asthma | Atenolol, Albuterol, Salmeterol |

| α-adrenergic | Benign prostatichypertrophy | Terazosin , doxazosin |

| Dopamine | Psychosis, Parkinson's | Aripiprazole, Ropinerole |

| Serotonin | Migraine, anxiety | Zolmitriptan, clozapine, buspirone |

| Opoid | Pain | Butarphanol |

| Angiotensin | Hypertension | Losartan, Eprosartan |

| Muscarinic acetylcoline | Alzheimer' s disease | Bethanechol, dicyclomine |

| Leukotriene | Asthma | Pranlukast |

The goal in developing drugs against the targets listed above is often to modulate the function of the human protein while the goal in developing drugs against pathogenic organisms is total inhibition, leading to the death of the pathogen. Antimicrobial drugs should be essential to the pathogen, have a unique function in the pathogen, be present only in the pathogen, and be able to be inhibited by a small molecule.

The target should be essential, in that it is a part of a crucial cycle in the cell, and its elimination should lead to the pathogen's death. The target should be unique: no other pathway should be able to supplement the function of the target and overcome the presence of the inhibitor. If the macromolecule satisfies all the outlined criteria to be a drug target but functions in healthy human cells as well as in a pathogen, specificity can often be engineered into the inhibitor by exploiting structural or biochemical differences between the pathogenic and human forms. Finally, the target molecule should be capable of inhibition by binding of a small molecule. Enzymes are often excellent drug targets because compounds are designed to fit within the active site pocket.

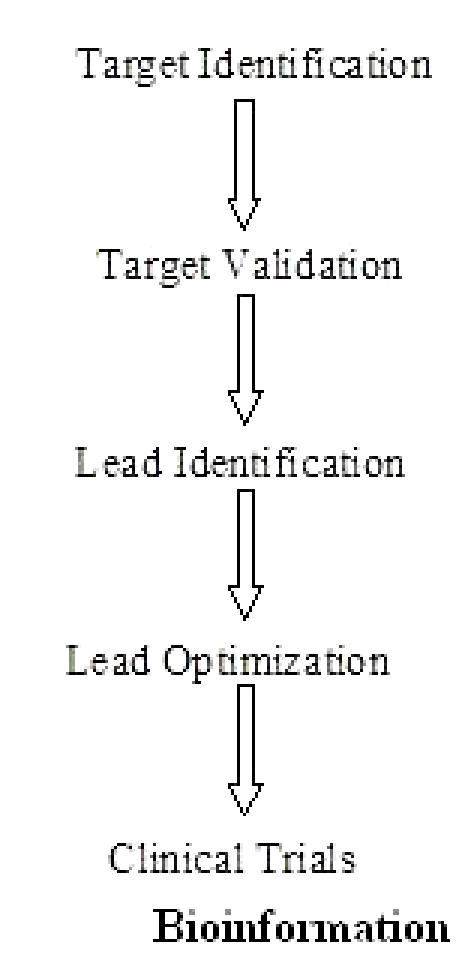

Structure based drug design

Drug discovery referred to, as ‘rational’ did not take flight until the first structures of the targets were solved. In 1897, Ehrlich suggested a theory called the side chain theory wherein he proposed that specific groups on the cells combine with the toxin. Ehrlich coined these side chains as receptors. Structure-based drug design of protein ligands has emerged as a new tool in medicinal chemistry. [20] The central assumption of structure-based drug design [21] is an iterative one as shown in Figure 3 and often proceeds through multiple cycles before an optimized lead goes into clinical trials.

Figure 3.

Steps involved in structure based drug design

The first cycle includes the cloning, purification and structure determination of the target protein or nucleic acid by one of three principal methods: X-ray crystallography, NMR or comparative modeling. Using computer algorithms, compounds or fragments of compounds from a database are positioned into a selected region of the structure.

These compounds are scored and ranked based on their steric and electrostatic interactions with the target site and the best compounds are tested further with biochemical assays. In the second cycle, structure determination of the target in complex with a promising lead from the first cycle, one with at least micromolar inhibition in vitro, reveals sites on the compound that can be optimized to increase potency. Additional cycles include synthesis of the optimized lead, structure determination of the new target: lead complex, and further optimization of the lead compound.

After several cycles of the drug design process, the optimized compounds usually show marked improvement in binding, and often, specificity for the target.

Evaluating a structure for structure based drug design

Once a target has been identified, it is necessary to obtain accurate structural information. There are three primary methods for structure determination that are useful for drug-design: X-ray crystallography, NMR, and homology modeling.

High-resolution crystal structures are the most common desired source of structural information for drug design, particularly for proteins that range in size from a few amino acids to 998kD. [22] Another advantage of crystallography is that ordered water molecules are visible in the experimental data and are often useful in drug design. A crystal structure should be evaluated for the resolution of the diffracted amplitudes (often simply called resolution); reliability, or R factors; coordinate error; temperature factors; and chemical correctness. Typically, crystal structures determined with data extending below 2.5 A0 are acceptable for drug design purposes since they have a high data to parameter ratio, and the placement of residues in the electron density map is unambiguous. The R factor and Rfree reported for a model are measures for the correlation between the model and experimental data. The Rfree value should be below 28% and ideally below 25%, and the R factor should be well below 25% in order to use the structure in drug design. If the only structure available for a particular target does not meet the resolution or R factor criteria, drug design projects can still be considered, but the results should be judged carefully.

Structures determined by nuclear magnetic resonance, using a concentrated protein or nucleic acid in solution are also valuable sources for drug design. [23] Since the target is in solution it is sometimes possible to interpret the dynamics of the target from the data. If no experimentally determined structure is available, a homology model can be used for drug design. [24,25] To evaluate a homology model, SWISS MODEL outputs a confidence factor per residue that reflects the amount of structural information used to create that portion of the model.

Using the structural information obtained through the above techniques, the structure is then prepared for drug design programs.

Present state of the art: Computer-aided drug design

Given the vast size of organic chemical space [26], drug discovery cannot be reduced to a simple “synthesize and test” drudgery. There is an urgent need to identify and/ or design drug-like molecules [27] from the vast expanse of what could be synthesized. In silico methods have the potential to reduce both time and cost in developing suggestions on drug/ lead-like molecules. Computational tools have the advantage for delivering new lead candidate more quickly and at lower cost. Drug discovery in the 21st century is expected to be different in at least two distinct ways: development of individualized medicine departing from genomic information and extensive use of in silico simulations to facilitate target identification, structure prediction and lead/drug discovery. The expectations from computational methods for reliable and expeditious protocols for developing suggestions on potential leads are continuously on the increase. Several conceptual and methodological concerns remain before an automation of drug design in silico could be contemplated.

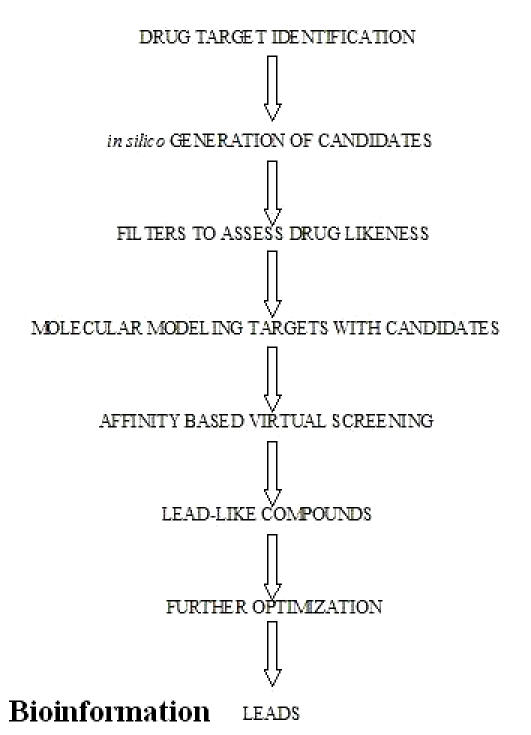

Computational methods are needed to exploit the structural information to understand specific molecular recognition events and to elucidate the function of the target macromolecule (Figure 4). This information should ultimately lead to the design of small molecule ligands for the target, which will block/activate its normal function and thereby act as improved drugs.

Figure 4.

Potential areas for in silico intervention in drug discovery

As structural genomics, bioinformatics, and computational power continue to explode with new advances, further successes in structure-based drug design are likely to follow. Each year, new targets are being identified; structures of those targets are being determined at an amazing rate, and capability to capture a quantitative picture of the interactions between macromolecules and ligands is accelerating.

Success of computer-assisted molecular design

The greatest success of computer-aided structure-based drug design to date is the HIV-1 protease inhibitors that have been approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration and reached the market. [28] There have been many successful computer-assisted molecular design attempts to involve the use of QSAR to improve activity of lead compounds. An example of the success story is that of SAR work carried out on antibacterial agent, Norfloxacin [29] that showed 6-fluro derivative of norfloxacin being 500 fold more potent over nalidixic acid. Other examples of drugs that were developed using computer –assisted drug design include Captopril (antihypertensive), Crixican (anti-HIV) [30], Teveten (antihypertensive) [31], Aricept( for Alzheimers disease) [32], Trusopt ( for Glaucoma) [30] and Zomig ( for migraine). [33]

Utility of Homology Models in the Drug Discovery Process

Advances in bioinformatics and protein modeling algorithms, in addition to the enormous increase in experimental protein structure information, have aided in the generation of databases that comprise homology models of a significant portion of known genomic protein sequences. Currently, 3D structure information can be generated for up to 56% of all known proteins. However, there is considerable controversy concerning the real value of homology models for drug design. Despite the numerous uncertainties that are associated with homology modeling, recent research has shown that this approach can be used to significant advantage in the identification and validation of drug targets, as well as for the identification and optimization of lead compounds. Homology model-based drug design has been applied to epidermal growth factor-receptor tyrosine kinase protein [34], Bruton's tyrosine kinase [35], Janus kinase 3 [36] and human aurora 1 and 2 kinases. [37] In the thesis, focus is on the application of homology models to the drug discovery process.

Conclusion

Thus, it can be said that pharmaceutical and biotechnology research has undergone great change. Traditionally, the crucial impasse in the industry's search for new drug targets was the availability of biological data. Now with the advent of human genomic sequence, bioinformatics offers several approaches for the prediction of structure and function of proteins on the basis of sequence and structural similarities. The protein sequence→structure→function relationship is well established and reveals that the structural details at atomic level help understand molecular function of proteins. Impressive technological advances in areas such as structural characterization of biomacromolecules, computer sciences and molecular biology have made rational drug design feasible and present a holistic approach.

Footnotes

Citation:Singh et al., Bioinformation 1(8): 314-320 (2006)

References

- 1.Goodford PJ, et al. Br J Pharmacol. 1980;68:741. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1980.tb10867.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blundell TL, et al. Adv Protein Chem. 1972;26:279. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davie EW, et al. Biochemistry. 1991;30:10363. doi: 10.1021/bi00107a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beddell CR, et al. Br J Pharmacol. 1976;57:201. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1976.tb07468.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blundell TL. Nature. 1996;384:23. doi: 10.1038/384023a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sibanda BL, et al. Nature. 1983;304:273. doi: 10.1038/304273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Campbell SF. Clin Sci. 2000;99:255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lapatto R, et al. Nature. 1989;342:299. doi: 10.1038/342299a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Varghese JN. Drug Dev Res. 1999;46:176. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hardy LW, Malikayil A. Curr Drug Discov. 2003:15. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 1999;10:571. doi: 10.1016/s0958-1669(99)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huynen MA, et al. Trends Genet. 1997;13:389. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(97)01255-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haq I. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2002;403:1. doi: 10.1016/S0003-9861(02)00202-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ecker DJ, Griffey RH. Drug Discovery Today. 1999;4:420. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(99)01389-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deisenhofer J, Smith JL. Curr Opin Struc Bio. 2001;11:701. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berman HM, et al. Nucleic Acids Research. 2000;28:235. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cacace A, et al. Drug Discovery Today. 2003;8:785. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02809-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venter JC, et al. Science. 2001;291:1304. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drews J. Science. 2000;287:1960. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5460.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klebe G. J Mol Med. 2000;78:269. doi: 10.1007/s001090000084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anderson AA. Chemistry & Biology. 2003;10:787. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2003.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Davis AM, et al. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2003;42:2718. doi: 10.1002/anie.200200539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pellecchia M, et al. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2002;1:211. doi: 10.1038/nrd748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Enyedy I, et al. J Med Chem. 2001;44:1349. doi: 10.1021/jm000395x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enyedy I, et al. J Med Chem. 2001;44:4313. doi: 10.1021/jm010016f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuntz ID. Science. 1992;257:1078. doi: 10.1126/science.257.5073.1078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walters PW, et al. Drug Discovery Today. 1998;3:160. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wlodawer A, Vondrasek J. Annu Rev Biophys Biomol Struct. 1998;27:249. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.27.1.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koga A, et al. J Med Chem. 1980;23:1358. doi: 10.1021/jm00186a014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Greer J, et al. J Med Chem. 1994;37:1035. doi: 10.1021/jm00034a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keenan RM. J Med Chem. 1993;36:1880. doi: 10.1021/jm00065a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kawakami Y, et al. Bioorg Med Chem. 1996;4:1429. doi: 10.1016/0968-0896(96)00137-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Glen RC, et al. J Med Chem. 1995;38:3566. doi: 10.1021/jm00018a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ghosh S, et al. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2001;1:129. doi: 10.2174/1568009013334188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mahajan S, et al. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:9587. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.14.9587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sudbeck EA, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:1569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vankayalapati H, et al. Mol Cancer Ther. 2003;2:283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]