Abstract

Background & Aims

Atypical Mycobacteria (ATB) are a miscellaneous collection of Mycobacteriaceae which also includes M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. leprae. In the paediatric population, ATB infections present with non-tender unilateral lymphadenopathy in a systemically well child. Initially the disease may be mistaken for a staphylococcal or streptococcal abscess. Inappropriate surgical incision and drainage is often performed and specimens may be sent for routine histopathology and bacteriology analysis only without considering Mycobacterial infection. The simple incision and drainage procedures can complicate the management and may result in a poor cosmetic outcome. ATB can go undiagnosed until the initial medical management has failed, these surgical interventions performed and the child remains symptomatic. We wish to highlight the importance of considering ATB infection in the differential diagnosis of a child with painless lymphadenitis.

Methods

An illustrative case report is described. A review of the paediatric data from the Mycobacterial laboratories in Northern Ireland over the last 14 years was performed to ascertain disease trends and prevalence of species.

Results

Overall an upward trend in the number of cases of cervical lymphadenitis caused by ATB infections in children was demonstrated. Organisms isolated in our population were M avium intracellulare, M malmoense and M interjectum.

Conclusions

We would like to present this data and a literature review, illustrated by case report, on the optimal management of these infections. We suggest that early definitive surgery is the management of choice, performed ideally by a surgeon with experience of this condition. A heightened awareness of these infections is essential to ensure appropriate early management.

Keywords: Mycobacterial Infection, Childhood infections

INTRODUCTION

Atypical Mycobacteria (ATB) are a miscellaneous collection of Mycobacterial species which also includes M. tuberculosis, M. bovis and M. leprae. Thirteen Atypical species are associated with human infection. These organisms are ubiquitous in the environment, existing in soil and water, as pathogens in birds or cattle and as pharyngeal flora in clinically well humans. Infected children are usually healthy with no immunological impairment and once appropriately treated there is full recovery. Immunocompromised individuals, such as HIV positive and immunodeficient patients, are susceptible to disseminated ATB infections.

ATB infections present with non-tender unilateral lymphadenopathy in a systemically well child. Initially the disease may be mistaken for a Staphylococcal or Streptococcal infection leading to inappropriate incision and drainage which can cause cosmetic complications. Consideration of an ATB diagnosis may not be given until medical or surgical therapy has failed.

We wish to highlight the importance of considering ATB infection in the differential diagnosis of a child with painless lymphadenitis. Over the past 14 years in Northern Ireland, we have observed an upward trend in the number of cases of cervical lymphadenitis caused by Atypical Mycobacteria in children.

CASE REPORT

Our 3-year old patient presented with a firm inflamed swelling in the right submandibular area. Initial medical management with intravenous antibiotics was ineffective. Fine needle aspiration of the lesion revealed acid-fast bacilli on Ziehl-Nielsen staining. Subsequent biopsy demonstrated a granulomatous reaction in keeping with a Mycobacterial infection.

Specific questioning revealed no family history of tuberculosis, abscesses or infections; there were no family pets, no exposure to birds and no unpasteurised milk consumption. An initial chest x-ray was normal and Mantoux testing was negative. Conventional anti-tuberculous therapy (Isoniazid, Rifampicin, and Pyrazinamide) was commenced. Definitive Culture at 6 weeks isolated Mycobacterium avium intracellulare. The prescription was altered to include Clarithromycin.

This boy remained on antimicrobial therapy for 9 months. When the therapy was discontinued the lesion appeared to be quiescent. However, following a minor episode of local trauma 6 months later, the lesion became swollen, inflamed and started to discharge. The original antibiotic therapy regimen was restarted. Subsequent referral was made to a supra-regional Paediatric Infectious Diseases unit because of failed medical management. Full surgical excision by a paediatric plastic surgeon was recommended as offering the best chance of complete recovery.

At operation an inflammatory mass of submandibular nodes and a large jugulodigastric node were resected. A minor branch of the facial nerve, which had become attenuated to the nodes, was excised and repaired under magnification. There was minimal cosmetic upset and only transient facial nerve weakness. Acid-fast bacilli were seen on initial pus analysis. Histology of the nodes confirmed granulomata & caseating necrosis in keeping with chronic Mycobacterial infection.

Excision was curative as two years later, our patient remains in good health and disease-free.

METHODS & RESULTS

Data on children with ATB-positive culture samples was collected from the only two Mycobacterial laboratories in Northern Ireland, based in Belfast City Hospital and Antrim Area Hospital. The records dated back to October 1990. Data was collected until October 2004.

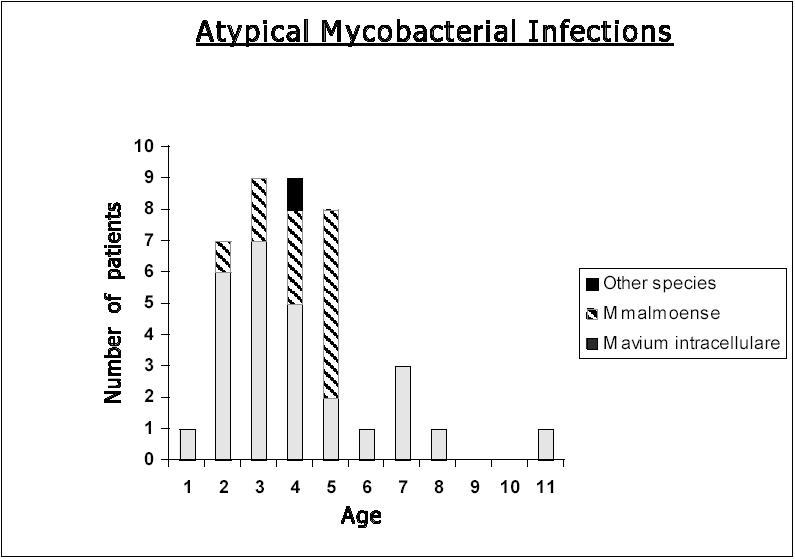

A total of 40 children aged 1 to 11 years (average age 3.6 years) were included in this study. All children presented with a unilateral neck swelling. Organisms isolated in this population were M. avium intracellulare (n=27), M. malmoense (n=12) and M. interjectum (n=1). Twenty eight out of the 40 children (70%) were female (fig 1). None of the patients suffered recurrence.

Overall an upward trend in the annual figures for ATB infections was demonstrated. The annual incidence over 14 years varied from 0 to 7 patients per year.

DISCUSSION

Atypical Mycobacterial infections in children are most frequently located in superior anterior cervical or in submandibular nodes (91%).1,2 The pre-auricular, post cervical, axillary and inguinal lymph nodes can also be involved. The children usually lack constitutional symptoms and present in 95% of cases with unilateral, subacute, progressive lymphadenopathy. The swelling is painless, firm and not erythematous. ATB infections have a winter and spring predominance and higher incidence in females.1 Person to person spread does not occur.

Mycobacterial lymphadenitis affects children aged 1-12 years. However, the majority of cases are reported in 1-5 year olds presumably because there is increased tendency of these children to put objects contaminated by soil or stagnant water into their mouths. It may also be due to the relative poor immunity to Mycobacteria found in this age group.3

Most of the affected children are healthy and are not immunocompromised. Markers of infection (WCC/CRP) and chest x-rays are normal. Mantoux testing may be positive or negative. Definitive diagnosis is confirmed by surgical excision of the node and recovery of the pathogen by culture. Exact species identification can take up to 8 weeks. Differential diagnoses include tuberculosis, cat-scratch disease, infectious mononucleosis, toxoplasmosis, brucellosis and malignancy (lymphoma).

The natural evolution of the cervical lymphadenitis varies; either the lymph nodes remain indurated for many months, or the disease progression results in softening, eruption, sinus formation and prolonged discharge. Other complications include reactivation after prolonged quiescence and damage to peripheral branch of facial nerve. The latter complication is because the preauricular nodes are often located within the parotid gland necessitating a limited parotidectomy with risk to the facial nerve.

Four large retrospective studies have demonstrated that surgical excision of infected nodes has a cure rate between 81% and 92%, rising to 95% if there is early surgical intervention.4–7 The evidence for anti-mycobacterial chemotherapy being effective in this infection is limited.5 Indeed it is accepted that in-vitro sensitivity testing may not reflect clinical response8 and it is our experience that many children respond inconsistently to these antibiotics. Our case typifies the difficulty in managing this infection with antimicrobial therapy only.

Surgical excision where possible in the hands of an experienced operator is the management of choice. However, surgical excision may be technically difficult because of adjacent and surrounding inflammation. Surgical excision of infected pre-auricular glands may result in a poor cosmetic outcome. In these situations a trial of antibiotics may be warranted. Anti-microbial chemotherapy directed at ATB can include aminoglycosides, macrolides and quinolones.3,5 We suggest that, where ATB infection is suspected, early referral to Paediatric Infectious Diseases or to a surgeon with experience in this area is indicated.

In conclusion, Atypical Mycobacterial infection presents as local cervical lymphadenitis in immunocompetent children. In our opinion we suggest that early definitive surgery by an experienced operator is the management of choice. Specimens should be sent for histopathology, bacteriology and Mycobacterial culture. A heightened awareness of these infections is essential to ensure appropriate early management.

The authors have no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chesney PJ. Nontuberculous mycobacteria. Ped Rev. 2002;23(9):300–9. doi: 10.1542/pir.23-9-300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Powell DA. Atypical mycobacteria. In: Behrman RE, Kliegman RM, Jenson HB, editors. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 17th ed. London: Philadelphia; Saunders; 2004. pp. 900–2. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Davies EG, Elliman DA, Hart CA, Nicoll A, Rudd PT, editors. Non-tuberculosis (atypical mycobacterial disease) Manual of childhood infections. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, London: W.B.Saunders; 2001. pp. 364–5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hazra R, Robson CD, Perez-Atayde AR, Husson RN. Lymphadenitis due to nontuberculous mycobacteria in children: presentation and response to therapy. Clin Infec Dis. 1999;28(1):123–9. doi: 10.1086/515091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.White MP, Bangash H, Goel KM, Jenkins PA. Non-tuberculous mycobacterial lymphadenitis. Arch Dis Child. 1986;61(4):368–71. doi: 10.1136/adc.61.4.368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fergusson JA, Simpson E. Surgical treatment of atypical mycobacterial cervicofacial adenitis in children. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69(6):426–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01593.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Makhani S, Postlethwaite KR, Renny NM, Kerawala CJ, Carton AT. Atypical cervico-facial mycobacterial infections in childhood. Br J Oral Maxillofacial Surg. 1998;36(2):119–22. doi: 10.1016/s0266-4356(98)90179-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Management of opportunist mycobacterial infections: Joint Tuberculosis Committee guidelines 1999. Subcommittee of the Joint Tuberculosis Committee of the British Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2000;55(3):210–8. doi: 10.1136/thorax.55.3.210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]