Abstract

Sinistral, or left-sided, portal hypertension is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. There are many causes of sinistral portal hypertension. The primary pathology usually arises in the pancreas and results in compression of the pancreatic vein. This compression causes backpressure in the left portal venous system and subsequent gastric varices. Management is usually surgical to treat the underlying pathology and splenectomy to decompress the left portal venous system.

This paper presents four cases of sinistral portal hypertension followed by a literature review of the reported causes and management issues.

Keywords: Left-sided portal hypertension, Sinistral portal hypertension, Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, Gastric varices

INTRODUCTION

Sinistral, or left-sided, portal hypertension is a rare cause of upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Isolated gastric varices result from thrombosis or obstruction of the splenic vein resulting in back pressure changes in the left portal system. The primary pathology usually arises in the pancreas and common aetiologies include pancreatitis and pancreatic neoplasms. Four illustrative case histories from patients with sinistral portal hypertension are discussed, followed by a review of the literature highlighting the aetiology and management of this condition.

CASE SERIES

Case 1

A 57 year old lady presented with upper gastrointestinal bleeding. She had a past medical history of retroperitoneal fibrosis and had a previous incidental finding of a cyst at the splenic hilum, associated with splenomegaly. No active bleeding source was identified at gastroscopy. Following a rebleed, she underwent a laparotomy, which revealed prominent veins around the gastric fundus and confirmed the presence of splenomegaly. Two large actively bleeding gastric varices were ligated. A second laparotomy, following a further rebleed ten days post-operatively, revealed a cystic inflammatory mass in the tail of the pancreas associated with the other features previously noted. There was no macroscopic evidence of liver cirrhosis. Deroofing of the cyst and splenectomy were carried out. Histology revealed benign chronic inflammatory features in keeping with a pancreatic pseudocyst. She has remained well with no further bleeding.

Case 2

A 53 year old man presented with melaena. He had no history of pancreatitis or alcohol excess. Gastroscopy revealed a mass of varices in the gastric fundus but no oesophageal varices or evidence of generalised portal hypertensive gastropathy. CT scan showed a mass between the tail of the pancreas and the splenic hilum. CA 19-9 was elevated at 624 IU/ml. Laparotomy confirmed a mass in the tail of the pancreas but it was unresectable due to infiltration of the posterior abdominal wall. Grossly dilated veins were also noted around the greater and lesser curves of the stomach. Biopsy revealed a neuroendocrine (islet cell) tumour of the pancreas. Immunohistochemistry confirmed a somatostatinoma. He has remained symptomatically well with no further bleeding.

Case 3

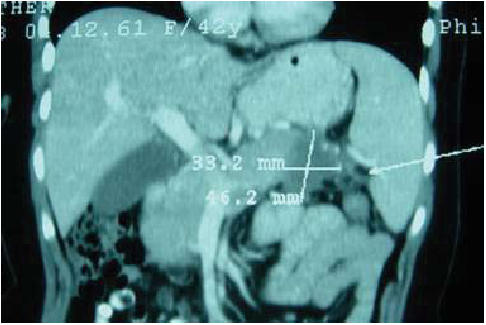

A 42 year old woman presented with an upper gastrointestinal bleed. She had no history of liver disease, alcohol excess or peptic ulcer disease. She had a past history of breast carcinoma. Gastroscopy failed to reveal an exact cause of the bleeding. There were no oesophageal varices and no duodenal ulceration. A laparotomy was undertaken for rebleeding and this showed bleeding gastric varices, which were ligated and decompressed by division of several of the short gastric vessels. CT scan revealed a low-density lesion in the tail of the pancreas associated with moderate splenomegaly (Figure). CA 19-9 was elevated at 779 IU/ml. Subsequent staging laparotomy revealed dilated vessels around the greater curvature and multiple intraperitoneal deposits in keeping with metastases. Histopathology indicated metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreatectomy and splenectomy were not attempted in view of the advanced disease.

Case 4

A 41 year old man had a past medical history of alcoholic pancreatitis and had a previous pancreatic pseudocystgastrostomy. He had multiple subsequent admissions for upper gastrointestinal bleeding requiring transfusion. Endoscopy revealed mild gastritis. Mesenteric angiography was negative. Laparotomy was undertaken following a massive rebleed. Dense adhesions were noted around the pancreas and spleen in keeping with chronic pancreatitis and the splenic vein was noted to be grossly dilated and thrombosed. Gastrotomy revealed brisk haemorrhage from the region of the gastrooesophageal junction. Splenectomy and distal pancreatectomy were undertaken followed by oesophageal transection to further control the bleeding. He has had no further bleeds three years following surgery.

DISCUSSION

Greenwald and Wasch first outlined the pathophysiology of left-sided portal hypertension in 1939.1 The development of this has been recognised as an important cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding resulting from gastric varices secondary to pathology in the pancreas. The splenic vein is susceptible in lesions of the pancreas due its close anatomical course along the superior pancreatic surface. The most common pathologies resulting in splenic vein thrombosis or obstruction and leading to the phenomenon of left-sided portal hypertension are chronic pancreatitis,2–4 pancreatic pseudocysts5 and pancreatic neoplasms. These include benign neoplasms, adenocarcinoma and functioning and non-functioning islet-cell (neuroendocrine) tumours.6–14 There are numerous other less common pathologies reported. These include iatrogenic splenic vein injury,15 post-liver transplantation,16,17 a wandering/ectopic spleen,18,19 infiltration by colonic tumour,20 spontaneous splenic vein thrombosis21 and perirenal abscess.22 This case series provides examples of four distinct causes, a pancreatic pseudocyst, a neuroendocrine tumour, an adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and chronic pancreatitis.

Splenic vein occlusion results in back pressure which is transmitted through its anastomoses with the short gastric and gastroepiploic veins and subsequently via the coronary vein into the portal system. This results in reversal of flow in these veins and the formation of gastric varices. The hypertension is confined to the left side of the portal system and is therefore distinct from the common phenomenon of generalised portal hypertension. Isolated gastric varices occur in left sided and generalised portal hypertension,23 however, the more common phenomenon of generalised portal hypertension should initially be excluded. The diagnosis of sinistral portal hypertension should be considered in all those with upper gastrointestinal bleeding associated with splenomegaly and normal liver function tests.24

Management of this condition traditionally involves surgical removal of the primary cause if possible, combined with splenectomy.2,5 Splenectomy decreases the arterial inflow into the left portal system by ligation of the splenic artery, resulting in decompression of the gastric varices. Prophylactic splenectomy may not be necessary in all patients with sinistral portal hypertension. The benefits of splenectomy are obvious in the management of those with severe upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage in order to rapidly reverse the cause. However, it may be acceptable to undertake a more conservative approach in those with more minor bleeds or in asymptomatic patients.25 Embolisation of the splenic artery has also been suggested as an alternative to splenectomy in high-risk patients5 or as a preoperative measure to reduce intra-operative blood loss.26

The overall prognosis for patients with sinistral portal hypertension is clearly dependant on the primary pathology but will invariably be poor in cases with a malignant primary pathology, as involvement of the splenic vein implies advanced infiltrative disease.27

CONCLUSION

Sinistral portal hypertension is an important cause of potentially life threatening upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage. Primary pancreatic pathology should be considered in patients with isolated gastric varices and in those with upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage associated with splenomegaly in the absence of chronic liver disease. Splenectomy is the appropriate management option when it is associated with major gastrointestinal haemorrhage.

Fig 1.

CT scan demonstrating a solid lesion in the tail of pancreas with splenomegaly and enlargement of the splenic vein (arrow).

Conflict of interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Greenwald HM, Wasch MG. The roentgenologic demonstration of esophageal varices as a diagnostic aid in chronic thrombosis of the splenic vein. J Pediatr. 1939;14:57–65. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sakorafas GH, Sarr MG, Farley DR, Farnell MB. The significance of sinistral portal hypertension complicating chronic pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 2000;179(2):129–33. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(00)00250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ruzicka M, Konecna D, Jordankova E. Portal hypertension as a complication of chronic pancreatitis. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46(28):2582–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Little AG, Moossa AR. Gastrointestinal haemorrhage from left-sided hypertension. An unappreciated complication of pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1981;141(1):153–8. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(81)90029-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Evans GR, Yellin AE, Weaver FA, Stain SC. Sinistral (left-sided) portal hypertension. Am Surg. 1990;56(12):758–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iwasaki T, Nagata Y, Watahiki H, Yamamoto H, Ogawa H. A rare case of serous cystadenoma of the pancreas presenting with left-sided portal hypertension. Surg Today. 1996;26(6):442–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00311934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chang CY. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma presenting as sinistral portal hypertension: an unusual presentation of pancreatic cancer. Yale J Biol Med. 1999;72(4):295–300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sahani D, Prasad SR, Maher M, Warshaw AL, Hahn PF, Saini S. Functioning acinar cell pancreatic carcinoma: diagnosis on mangafodipir trisodium (Mn-DPDP)-enhanced MRI. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2002;26(1):126–8. doi: 10.1097/00004728-200201000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caggiano AV, Adams DB, Metcalf JS, Anderson MC. Neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas in a patient with pernicious anemia. Am Surg. 1990;56(6):347–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dalvi AN, Rege SA, Bapat MR, Abraham P, Joshi AS, Bapat RD. Nonfunctioning islet cell tumor presenting with ascites and portal hypertension. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2002;21(6):227–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watase M, Sakon M, Monden M, Miyoshi Y, Tono T, Ichikawa T, et al. A case of splenic vein occlusion caused by the intravenous tumor thrombus of nonfunctioning islet cell carcinoma. Surg Today. 1992;22(1):62–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00326127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sheen-Chen SM, Eng HL, Wan YL, Chou FF. Acinar cell carcinoma of the pancreas: a rare cause of left-sided portal hypertension. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86(8):1070–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz DC, Benjamin SB. Islet cell carcinoma of the pancreas presenting as bleeding from isolated gastric varices. Report of a case and review of the literature. Dig Dis Sci. 1991;36(2):241–4. doi: 10.1007/BF01300765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chellapa M, Yee CK, Gill DS. Left-sided portal hypertension from malignant islet cell tumour of the pancreas: review with a case report. J R Coll Surg Edinb. 1986;31(4):251–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsuchida S, Ku Y, Fukumoto T, Tominaga M, Iwasaki T, Kuroda Y. Isolated gastric varices resulting from iatrogenic splenic vein occlusion: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33(7):542–4. doi: 10.1007/s10595-002-2519-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Malassagne B, Soubrane O, Dousset B, Legmann P, Houssin D. Extrahepatic portal hypertension following liver transplantation: a rare but challenging problem. HPB Surg. 1998;10(6):357–63. doi: 10.1155/1998/81832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stevenson WC, Sawyer RG, Pruett TL. Recurrent variceal bleeding after liver transplantation—persistent left-sided portal hypertension. Transplantation. 1992;53(2):493–5. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199202010-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angeras U, Almskog B, Lukes P, Lundstam S, Weiss L. Acute gastric hemorrhage secondary to wandering spleen. Dig Dis Sci. 1984;29(12):1159–63. doi: 10.1007/BF01317093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melikoglu M, Colak T, Kavasoglu T. Two unusual cases of wandering spleen requiring splenectomy. Eur J Pediatr Surg. 1995;5(1):48–9. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1066163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Seenu V, Goel AK, Shukla NK, Dawar R, Sood S. Hodgkin's lymphoma of colon: an unusual cause of isolated splenic vein obstruction. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1994;13(2):70–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldberg S, Katz S, Naidich J, Waye J. Isolated gastric varices due to spontaneous splenic vein thrombosis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1984;79(4):304–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koklu S, Koksal A, Yolcu OF, Bayram G, Sakaogullari Z, Arda K, Sahin B. Isolated splenic vein thrombosis: an unusual cause and review of the literature. Can J Gastroenterol. 2004;18(3):173–4. doi: 10.1155/2004/801576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nagral S, Shah S, Gandhi M, Mathur SK. Bleeding isolated gastric varices: a retrospective analysis. Indian J Gastroenterol. 1999;18(2):69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Glynn MJ. Isolated splenic vein thrombosis. Arch Surg. 1986;121(6):723–725. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1986.01400060119018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Loftus JP, Nagorney DM, Illstrup D, Kunselman AR. Sinistral portal hypertension. Splenectomy or expectant management. Ann Surg. 1993;217(1):35–40. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199301000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Adams DB, Mauterer DJ, Vujic IJ, Anderson MC. Preoperative control of splenic artery inflow in patients with splenic venous occlusion. South Med J. 1990;83(9):1021–4. doi: 10.1097/00007611-199009000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hwang TL, Jan YY, Jeng LB, Chen MF, Hung CF, Chiu CT. The different manifestation and outcome between pancreatitis and pancreatic malignancy with left-sided portal hypertension. Int Surg. 1999;84(3):209–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]