Abstract

In myelodysplasias and acute myeloid leukemias, abnormalities in erythroid development often parallel abnormalities in megakaryocytic development. Erythroleukemic cells in particular have been shown to possess the potential to undergo megakaryocytic differentiation in response to a variety of stimuli. Whether or not such lineage plasticity occurs as a consequence of the leukemic phenotype has not previously been addressed. In this study, highly purified primary human erythroid progenitors were subjected to stimuli known to induce megakaryocytic differentiation in erythroleukemic cells. Remarkably, the primary erythroid progenitors rapidly responded with morphological and immunophenotypic evidence of megakaryocytic differentiation, equivalent to that seen in erythroleukemic cells. Even erythroblasts expressing high levels of hemoglobin manifested partial megakaryocytic differentiation. These results indicate that the lineage plasticity observed in erythroleukemic cells reflects an intrinsic property of cells in the erythroid lineage rather than an epiphenomenon of leukemic transformation.

Findings in human acute leukemias have long suggested a close developmental relationship between the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages. In acute leukemia of the erythroid lineage (erythroleukemia, FAB M6), coexisting dysplasia of the megakaryocytic lineage is a common morphological finding. 1 Similarly in many cases of primary myelodysplasia, in particular the 5q-syndrome, maturation defects show co-restriction to the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages. Conversely, in megakaryocytic malignancies, especially those associated with Down’s syndrome, coexisting dyserythropoiesis may occur frequently. Biphenotypism at the immunophenotypic and molecular levels has been confirmed on blasts in cases of erythroleukemia and megakaryocytic leukemia. 2,3 This lineage infidelity has also been observed in vitro, wherein erythroleukemic cell lines treated with phorbol esters undergo extensive megakaryocytic differentiation. 4-7 Thus, leukemic cells with clear evidence of erythroid differentiation, such as high-level expression of glycophorin A (GPA), often manifest lineage plasticity, ie, a capacity to execute lineage switching.

In normal human marrow, a common progenitor for the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages, the BFU-E/MK, resides in an undifferentiated compartment of cells with the CD34+, CD38− phenotype. 8 Expression of the erythroid markers GPA and hemoglobin occurs much later at mid to late stages of erythroid development, clearly after lineage commitment. 9 The nature of the erythroid versus megakaryocytic lineage commitment event by the BFU-E/MK remains unknown: both instructive and stochastic models have been proposed. 10,11 One feature generally agreed on is the irreversible nature of physiological lineage commitment. Thus, primary human erythroblasts are defined as precursors that exclusively express red blood cell lineage-specific genes and are considered to lack the lineage plasticity observed in their leukemic counterparts.

Two alternative explanations might explain the biphenotypism and lineage plasticity so commonly seen in erythroid and megakaryocytic malignancies. 1) The lineage plasticity might occur secondary to the transformation process. 2) The lineage plasticity may reflect an intrinsic property of normal hematopoietic progenitors. To distinguish between these possibilities, we subjected highly purified, primary human erythroblasts, at mid to late stages of differentiation, to a conditioned medium stimulus that we have published as capable of inducing rapid megakaryocytic differentiation in erythroleukemic cells. 12 As a negative control, the erythroblasts were treated with thrombopoietin (TPO), which does not induce megakaryocytic lineage commitment but potently expands precommitted megakaryocytic progenitors. 13,14 Both adult and cord blood erythroblasts showed morphological and immunophenotypic evidence of megakaryocytic differentiation within 48 hours of treatment with conditioned medium. When switched to medium with TPO, erythroblasts pre-exposed to conditioned medium showed prolonged survival and ongoing megakaryocytic differentiation. By contrast, erythroblasts treated directly with TPO, without exposure to conditioned medium, showed no evidence of megakaryocytic differentiation and underwent extensive cell death. Our data thus indicate that: 1) human erythroblasts, even relatively late in the course of their development, retain potential for megakaryocytic differentiation, and 2) the lineage plasticity of erythroleukemic cells reflects a property of normal erythroid progenitors.

Materials and Methods

Isolation and Expansion of Human Erythroblasts

G-CSF mobilized, adult peripheral blood CD34+ stem cells were obtained from the Johns Hopkins Oncology Center Graft Engineering Laboratory using a Miltenyi CliniMACS immunomagnetic separation device per the manufacturer’s specifications (Miltenyi Biotec, Sunnyvale, CA). The CD34+ stem cells were initially expanded for 3 days in LGM3 serum-free medium (Clonetics Corp., Walkersville, MD) supplemented with stem cell factor (SCF) (25 ng/ml), interleukin (IL)-3 (10 ng/ml), and IL-6 (10 ng/ml). To promote erythroid expansion, cells were then transferred into LGM3 supplemented with EPO (3 U/ml), as well as SCF (25 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), and IL-6 (10 ng/ml). Erythropoietin was purchased from StemCell Technologies (Vancouver, Canada); all other cytokines were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). After 2 days of culture in medium containing EPO, cells were subjected to flow sorting for GPA bright (GPA++) erythroblasts. In a typical experiment, ∼10 8 cells were stained with a phycoerythrin conjugated-murine monoclonal antibody to GPA (clone GA-R2; Pharmingen, San Diego, CA) at a concentration of 2 μg/ml. In parallel, an aliquot of cells was stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated isotype control antibody (IgG2bκ, Pharmingen) also at 2 μg/ml. GPA++ cells were sorted on a Becton Dickinson FACS Vantage cell sorter (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA), typically yielding ∼10 7 cells with a purity of >99% (Figure 1) ▶ . Sorted GPA++ cells were expanded an additional 2 days in LGM3 supplemented with EPO (3 U/ml), as well as SCF (25 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), and IL-6 (10 ng/ml). The resultant population of cells used for experiments was typically >80% hemoglobin A-positive by immunofluorescence microscopy (Figure 2) ▶ .

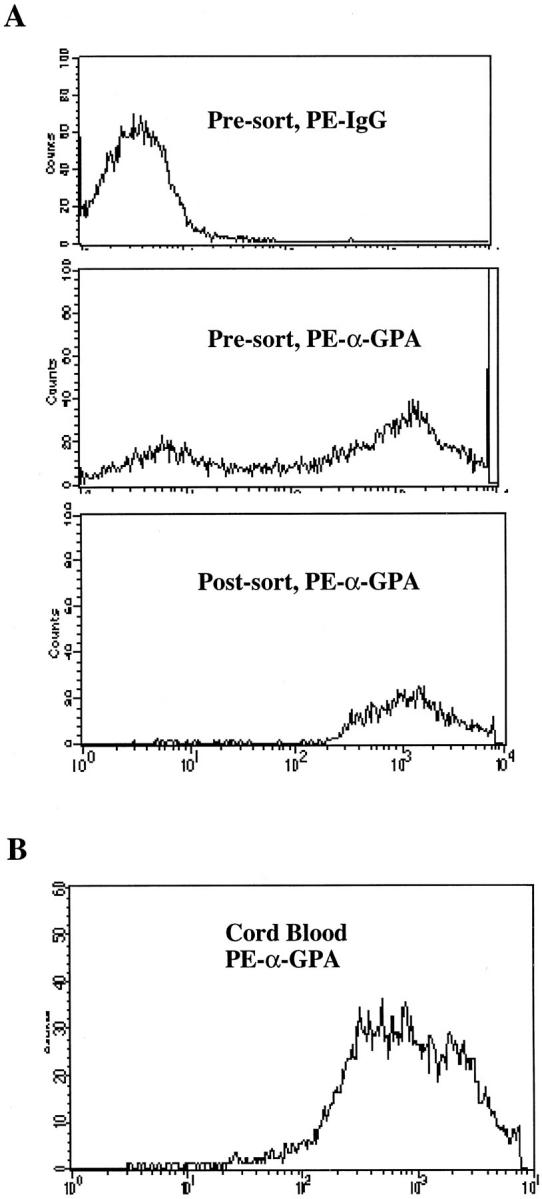

Figure 1.

Flow cytometric analysis of primary human hematopoietic progenitor cells for expression of the erythroid surface antigen GPA. A: Presort population of adult CD34+ stem cells grown in erythroid media and stained with negative control antibody (top). Middle: Presort population of adult CD34+ stem cells grown in erythroid media and stained with a phycoerythrin conjugated monoclonal antibody to GPA; note that ∼50% of the cells are GPA bright (++) erythroblasts. Bottom: Postsort population of adult GPA++ erythroblasts; the purity of this population was 99.6%. B: Cord blood erythroblasts expanded 6 days in erythroid media were stained with a phycoerythrin-conjugated monoclonal antibody to GPA; note that 99% of the cells are GPA bright (++) erythroblasts.

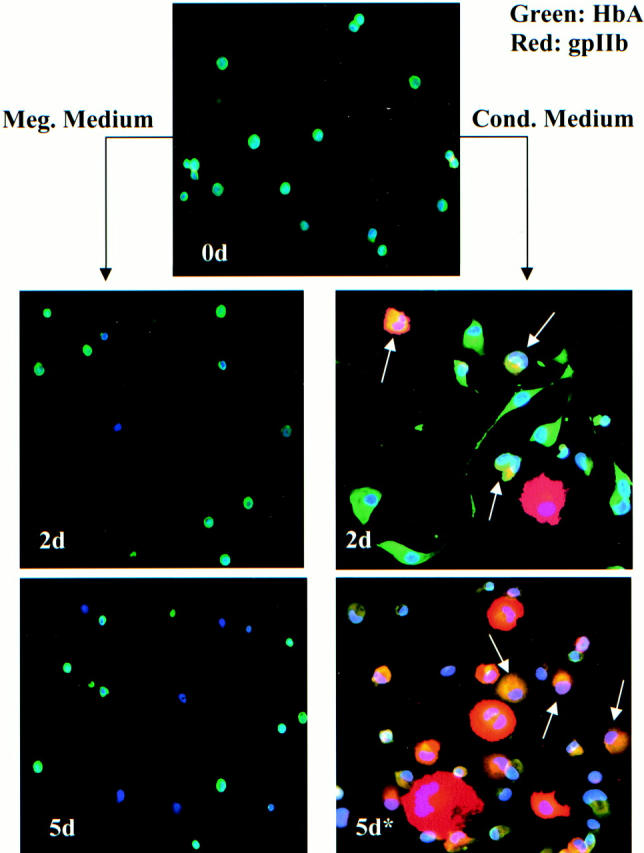

Figure 2.

Multicolor immunofluorescence staining of purified adult erythroid progenitor cells depicted in Figure 1A ▶ , bottom. Cells were stained with a combination of antibodies to HbA (FITC detection) and platelet glycoprotein gpIIb (Texas Red detection), as well as with the nuclear dye Hoechst 33258. Top: The starting population of cells (0d) consisting of small, round HbA++, gpIIb− erythroblasts (green). Right: Cells treated with conditioned medium for 48 hours (2d) and with conditioned medium 48 hours followed by 3 days of megakaryocytic medium (5d*). Note the striking megakaryocytic transformation of erythroblasts exposed to conditioned medium even at 2 days. The arrows indicate transitional cells with combined erythroid and megakaryocytic features. Cells co-expressing high levels of HbA (green) and high levels of gpIIb (red) appear yellow. Left: Cells transferred directly to megakaryocytic medium for 48 hours (2d) and for 5 days (5d). Note that this TPO-containing medium does not induce megakaryocytic differentiation in the erythroblasts. Original magnification for all panels is ×200.

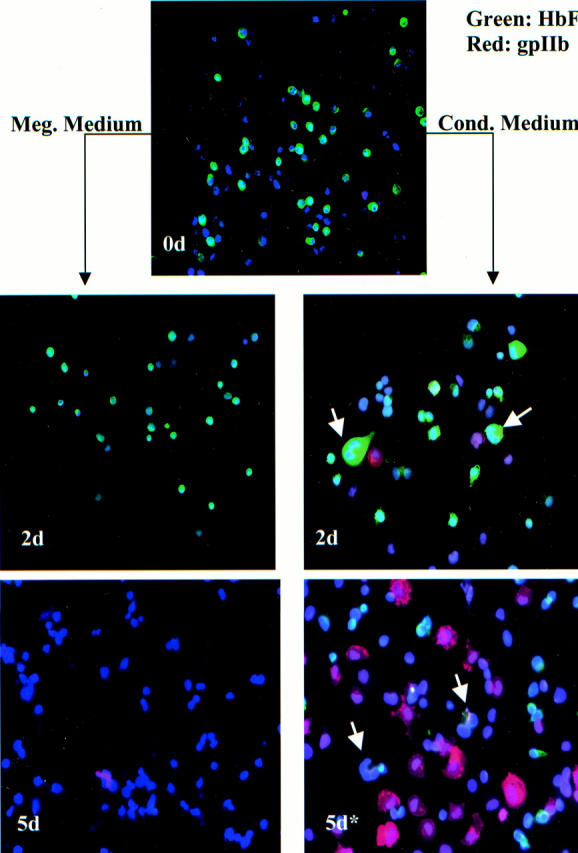

Human cord blood erythroid progenitor cells were purchased from Poietic Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD). These cells were expanded in LGM 3 supplemented with EPO (3 U/ml) as well as SCF (25 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), and IL-6 (10 ng/ml). After a total of 6 days of expansion in erythroid media, cells were used for experiments and consisted of a population >99% GPA++ (Figure 1) ▶ and >50% hemoglobin F-positive (Figure 3) ▶ .

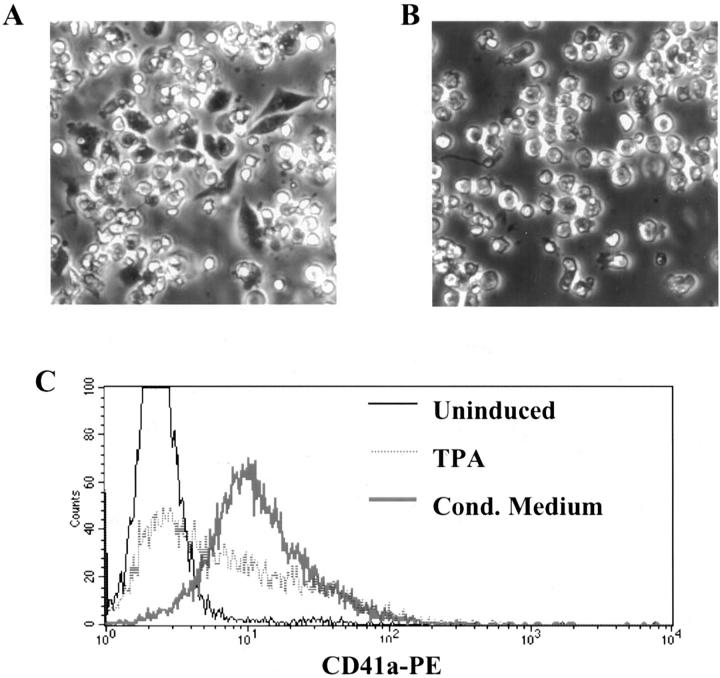

Figure 3.

Morphological and immunophenotypic comparison of the effects of conditioned medium versus the effects of TPA on primary purified human erythroblasts. A: Phase contrast microscopy of erythroblasts treated for 48 hours with conditioned medium (original magnification, ×200). Note the frequent cells undergoing spreading and enlargement characteristic of megakaryocytic differentiation. B: Phase contrast microscopy of erythroblasts treated for 48 hours with 25 nmol/L TPA (original magnification, ×200). Note the absence of cells undergoing spreading and enlargement. C: Flow cytometric comparison of CD41a expression on primary erythroblasts either untreated, treated with conditioned medium for 48 hours, or treated with 25 nmol/L TPA for 48 hours. Note the enhanced up-regulation of CD41a in the conditioned medium-treated cells as compared with the TPA-treated cells.

Differentiation Induction

Conditioned media was generated by treating HEL cells (American Type Culture Collection, Rockville, MD) in RPMI 1640 and 10% fetal bovine serum with 25 nmol/L 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-ester (TPA) for 3 days, followed by harvesting and spin-dialysis of supernatant. The dialyzed conditioned media was then subjected to 0.2-μ filter sterilization and stored in aliquots at −20°C. For differentiation induction, erythroid progenitors were resuspended at a density of 0.2 to 0.5 × 10 6 cells/ml in conditioned media supplemented with SCF (25 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (10 ng/ml), and TPO (50 ng/ml). For control experiments, erythroid progenitors at a similar density were resuspended in nonconditioned LGM3, similarly supplemented with SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and TPO. After a 48-hour exposure to conditioned or control media, cells were either harvested or changed to LGM3 supplemented with SCF (25 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (10 ng/ml), and TPO (50 ng/ml) for additional culture.

Immunofluorescence and Flow Cytometry

Untreated erythroid progenitors were directly seeded onto poly-l-lysine-coated coverslips and allowed to adhere 15 minutes at 37°C. Similarly, erythroid progenitors shifted directly to megakaryocytic media were harvested at the indicated time points and seeded onto poly-l-lysine coverslips. Cells treated with conditioned media undergo efficient adhesion directly to glass coverslips; these cells were therefore seeded onto coverslips during initiation of treatment with conditioned media. After 48 hours of conditioned media, coverslips were either harvested for fixation or the media was changed to LGM3 supplemented with SCF (25 ng/ml), IL-3 (10 ng/ml), IL-6 (10 ng/ml), and TPO (50 ng/ml) for the indicated durations. For fixation, coverslips were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) followed by incubation in 4% paraformaldehyde/PBS 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were preblocked and permeabilized by incubation 30 minutes at room temperature in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100/5% normal goat serum. The primary antibodies, diluted 1/100 in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100, consisted of the murine monoclonal anti-CD41b (clone HIP2, Pharmingen) and rabbit polyclonal anti-hemoglobin A (AXL 241; Accurate Chemical & Scientific Corp., Westbury, NY). After extensive washing, cells were subjected to the secondary antibodies consisting of Texas Red-conjugated goat anti-mouse Ig (Southern Biotechnology Associates, Birmingham, AL) and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated goat anti-rabbit Ig (Cappel/Organon Technika, West Chester, PA) both at a dilution of 1/160 in PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 with 5 μg/ml Hoechst 33258 (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cord blood cells were stained for hemoglobin F rather than for hemoglobin A, using direct FITC-conjugated murine monoclonal anti-hemoglobin (clone B-1; Caltag, Burlingame, CA); this antibody was applied after primary and secondary antibodies for CD41 had been applied and cells had been extensively washed. After all staining steps, the cells were washed with PBS/0.1% Triton X-100, followed by PBS only. Slides were viewed on a Nikon Microphot-SA epifluorescent microscope using a Hamamatsu CCD camera interfaced with a Power Macintosh G3. Imaging software consisted of Openlab (Imaging Processing & Vision Company, Ltd., Coventry, U.K.).

For flow cytometry, cells were stained with phycoerythrin-conjugated murine monoclonal anti-GPA, an isotype matched control, or anti-CD41a (Pharmingen) as described above for cell sorting. Cells were analyzed on a FACScan system with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson).

Results

Isolation of Highly Purified Adult Human Erythroblasts

Adult human hematopoietic stem cells were grown in culture conditions supporting erythroid development. 9 At day 5 of culture, ∼50% of the cells displayed the GPA++ phenotype that is highly specific for erythroblasts at mid to late phases of differentiation; 9 these cells are illustrated in the presort population in Figure 1A ▶ (middle). Flow cytometric sorting was used to isolate the GPA++ cells, yielding a postsort population of 99.6% purity (Figure 1A ▶ , bottom). This approach for isolation of highly purified erythroblasts, used on two additional occasions, consistently yielded >99.0% GPA++ cells. Immunofluorescent staining of the postsort population from Figure 1A ▶ showed that >80% of the cells expressed high levels of HbA (Figure 2 ▶ , 0d).

Induction of Megakaryocytic Differentiation in Primary Adult Erythroblasts

In a previous publication we have shown that treatment of erythroleukemic cell lines such as K562 and HEL with the phorbol ester TPA causes the elaboration of autocrine factors that promote megakaryocytic lineage commitment. 12 Dialyzed, conditioned medium from TPA-treated erythroleukemic cells retains the capacity to induce megakaryocytic differentiation, with megakaryocytic markers appearing after 1 to 2 days. 12 To examine this process in primary human cells, the highly purified primary erythroblasts were exposed to conditioned medium for 2 days (Figure 2 ▶ , 2d). To prevent apoptosis from growth factor withdrawal, the conditioned media was supplemented with a cytokine mixture containing SCF, interleukin 3 (IL-3), interleukin 6 (IL-6), and TPO. Because of the toxic effects of prolonged culture in conditioned medium, the cells were switched after 2 days into megakaryocyte medium (serum-free LGM3 with SCF, IL-3, IL-6, and TPO). In control cultures, erythroblasts were switched directly to megakaryocyte medium and analyzed at 2 days and 5 days of culture. Both control and induced cultures contained identical cytokine supplementation. Cells were analyzed at 0 days (Figure 2 ▶ , 0d), 2 days (Figure 2 ▶ , 2d), and 5 days (Figure 2 ▶ , 5d) by multicolor immunofluorescent staining for: HbA (FITC), the megakaryocytic integrin gpIIb (Texas Red), and nuclear morphology (Hoechst 33258).

As shown in Figure 2 ▶ , the starting population (0d) consisted of small round cells with bright cytoplasmic expression of HbA (green). Notably, <1% of this starting population expressed gpIIb (red). Control cultures of the erythroblasts directly switched to megakaryocytic medium (left column) showed no evidence of megakaryocytic outgrowth at 2 days (2d) or 5 days (5d). At 2 days of control culture, the cells resembled the starting population, and at 5 days extensive cell death was evident. Similar results were also obtained with switching of cells to unconditioned RPMI medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and identical cytokines. These results indicated that: 1) standard megakaryocytic cytokines do not induce erythroblasts to undergo megakaryocytic differentiation, and 2) the starting erythroblast population was not contaminated by committed megakaryocytic progenitors.

By contrast, erythroblasts treated for 2 days with conditioned medium showed striking phenotypic transformation (Figure 2 ▶ , right column, 2d). These cells demonstrated spreading and pseudopod extension, as seen in erythroleukemic cells undergoing megakaryocytic differentiation. Several cells displayed nuclear lobulation/polyploidization and up-regulation of gpIIb (red). Most striking was the abundance of hybrid or transitional cells retaining bright HbA expression coupled with cell spreading, nuclear lobulation, and gpIIb up-regulation. The arrows indicate cells co-expressing HbA and gpIIb (yellow). When switched into megakaryocytic medium, the cells exposed to conditioned medium continued to progress along the megakaryocytic lineage (Figure 2 ▶ , right column, 5d). These cells showed further enlargement, polyploidization, and gpIIb up-regulation; strikingly several of the cells strongly co-expressed HbA and gpIIb (yellow) (arrows). Table 1 ▶ shows the quantitative results from two independent experiments each using separately purified adult human erythroblasts.

Table 1.

Quantitative Analysis of Morphologic and Immunophenotypic Features of Purified Adult Human Erythroblasts Subjected to either Megakaryocytic Medium (Controls) or Conditioned Medium.

| Treatment | % HgA+ | % gpIIb+ | % Polyploid |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2d Meg. Medium (Exp. #1) | 35% (108/313) | 1.3% (4/313) | 0% (0/313) |

| 2d Meg. Medium (Exp. #2) | 31% (51/166) | 0.6% (1/166) | 0% (0/166) |

| 2d Cond. Medium (Exp. #1) | 20% (74/361) | 13% (48/361) | 12% (42/361) |

| 2d Cond. Medium (Exp. #2) | 20% (60/296) | 16% (48/296) | 7.0% (20/296) |

| 5d Meg. Medium | 83% (248/298) | 2.0% (6/298) | 0.7% (2/298) |

| 2d Cond. Med.+ 3d Meg. Med. (Exp. #1) | 13% (44/340) | 31% (104/340) | 10% (35/340) |

| 2d Cond. Med.+ 3d Meg. Med. (Exp. #2) | 7.0% (22/321) | 24% (77/321) | 16% (53/321) |

Data from two independent experiments are shown. Results are shown as the percentage of positive cells (positive cells/total cells counted).

Meg., megakaryocytic; Cond., conditioned; Exp. experiment.

Control experiments addressed whether the effects of the conditioned medium on the erythroblasts were simply secondary to carryover of phorbol ester. Figure 3, A and B ▶ , shows the distinct phase-contrast morphologies of cells treated with conditioned medium (Figure 3A) ▶ versus phorbol ester (Figure 3B) ▶ . Flow cytometry demonstrated clear up-regulation of the megakaryocytic antigen CD41a in the majority of cells treated with conditioned medium (Figure 3C) ▶ . By contrast up-regulation of CD41a occurred only in a minority of cells treated with phorbol ester (Figure 3C) ▶ .

Induction of Megakaryocytic Differentiation in Cord Blood Erythroblasts

As compared with adult stem cells, cord blood stem cells possess several distinct properties, for example generation of HbF+ erythroblasts and relative deficiency in megakaryocyte production. 15 Therefore, we also examined the capacity of cord blood erythroblasts for megakaryocytic differentiation. Figure 1B ▶ shows that >99% of the starting population consisted of GPA++ cells. Multicolor immunofluorescent staining showed the starting population to be ∼60% HbF+ (green), 1% gpIIb+ (red), and 0% polyploid (Figure 4 ▶ , 0d, and Table 2 ▶ ). As with the adult erythroblasts, control cultures with megakaryocytic medium caused no phenotypic change at 2 days (Figure 4 ▶ , left column, 2d) and extensive cell death at 5 days (Figure 4 ▶ , left column, 5d). Exposure of the cord blood erythroblasts to conditioned medium for 2 days induced megakaryocytic differentiation with spreading of cells, nuclear lobulation/polyploidization, and up-regulation of gpIIb (red) (Figure 4 ▶ , right column, 2d). Again, switching of cells from conditioned medium to megakaryocytic medium was associated with ongoing megakaryocytic differentiation, illustrated by marked up-regulation of gpIIb (red) in many of the cells (Figure 4 ▶ , right column, 5d). At both 2 days and 5 days of induction, frequent hybrid or transitional cells (arrows) displayed both erythroid and megakaryocytic features. Quantitative analysis of two independent experiments with cord blood erythroblasts is shown in Table 2 ▶ . These data confirm that cord blood erythroblasts, like adult erythroblasts, reproducibly respond to conditioned medium by undergoing megakaryocytic differentiation, consisting of down-regulation of hemoglobin expression, up-regulation of gpIIb expression, and acquisition of lobulated/polyploid nuclei.

Figure 4.

Multicolor immunofluorescence staining of cord blood erythroid progenitor cells depicted in Figure 1B ▶ . Cells were stained with a combination of FITC-conjugated anti-HbF, anti-gpIIb (Texas Red detection), and Hoechst 33258. Top: The starting population of cells (0d) consisting predominantly of small, round HbF++, gpIIb− erythroblasts (green). Right: Cells treated with conditioned medium for 48 hours (2d) and with conditioned medium for 48 hours followed by 3 days of megakaryocytic medium (5d*). As in Figure 2 ▶ , note the striking megakaryocytic transformation of erythroblasts exposed to conditioned medium even at 2 days. The arrows indicate transitional cells with combined erythroid and megakaryocytic features. Left: Cells transferred directly to megakaryocytic medium for 48 hours (2d) and for 5 days (5d). Note that the TPO-containing medium does not induce megakaryocytic differentiation in the erythroblasts; extensive cell death is evident at 5 days. Original magnification for all panels is ×200.

Table 2.

Quantitative Analysis of Morphologic and Immunophenotypic Features of Cord Blood Erythroblasts Subjected to Either Megakaryocytic Medium (Controls) or Conditioned Medium.

| Treatment | % HgF+ | % gpIIb+ | % Polyploid |

|---|---|---|---|

| Starting population | 59% (188/318) | 1.2% (4/318) | 0% (0/318) |

| 2d Meg. Medium (Exp. #1) | 60% (196/324) | 1.2% (4/324) | 0.6% (2/324) |

| 2d Meg. Medium (Exp. #2) | 52% (167/320) | 0.3% (1/320) | 0% (0/320) |

| 2d Cond. Medium (Exp. #1) | 33% (101/305) | 16% (48/305) | 14% (43/305) |

| 2d Cond. Medium (Exp. #2) | 38% (120/317) | 18% (58/317) | 8.5% (27/317) |

| 5d Meg. Medium* | 2.2% (7/324) | 0.6% (2/324) | 0.3% (1/324) |

| 2d Cond. Med.+ 3d Meg. Med. (Exp. #1) | 20% (71/358) | 31% (110/358) | 16% (59/358) |

| 2d Cond. Med.+ 3d Meg. Med. (Exp. #2) | 27% (82/308) | 31% (95/308) | 11% (35/308) |

*Sample had <5% viable intact cells.

Data from two independent experiments are shown. Results are shown as the percentage of positive cells (positive cells/total cells counted).

Meg., megakaryocytic; Cond., conditioned; Exp. experiment.

Discussion

Our data indicate that the capacity for switching to the megakaryocytic lineage is an intrinsic property of human erythroblasts, even relatively late in their development. Several lines of evidence argue against megakaryocytic contamination of the starting erythroid populations as a cause for these results. Firstly, the starting population of cells, both for adult erythroblasts and for cord blood erythroblasts, showed >99% purity as assessed by high-level GPA expression. Secondly, no significant megakaryocytic outgrowth was observed when the cells were cultured up to 5 days in highly effective megakaryocytic growth media. In fact, culture of the erythroblasts in megakaryocytic growth media eventually led to extensive cell death, as has been previously described. 16 Thirdly, frequent transitional cells with combined erythroid and megakaryocytic features were observed, particularly with the adult erythroblast cultures (Figure 2) ▶ . This combination included large polyploid cells with high levels of Hb expression, as well as cells showing strong co-expression of Hb and gpIIb.

Lumelsky and Schwartz 17 previously provided evidence for minimal megakaryocytic differentiation in long-term human erythroid cultures treated with phorbol ester. However, the starting population in that study did not consist of well-defined, highly purified erythroblasts, and the long-term culture conditions allowed for the possibility of megakaryocytic outgrowth rather than actual lineage plasticity. The minimal degree of megakaryocytic differentiation they found agrees with our finding that TPA lacks efficacy in the induction of megakaryocytic differentiation (Figure 3) ▶ .

Vannucchi and colleagues 18 have described a population of cells in mouse marrow and spleens that co-expresses the erythroid antigen TER-119 with the megakaryocytic antigen 4A5 (gpV). By reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction, these cells demonstrate co-expression of several erythroid (α-globin, β-globin, EpoR) and several megakaryocytic (AchE, gpIIb) transcripts. Unlike the BFU-E/MK progenitors described by Debili and colleagues, 8 the TER-119+/4A5+ cells appear to be very late in the course of differentiation and can give rise to clear erythroblasts or megakaryocytes within 24 to 48 hours of culture. Thus the possibility exists that the TER-119+/4A5+ cells identified by Vannucchi and colleagues 18 could actually represent physiological cells in transition from erythroid to megakaryocytic lineages. The human counterpart of the murine TER-119+/4A5+ cells may consist of the GPA+/CD41+ bone marrow cells recently described by Basch and colleagues. 19

Our results provide a physiological basis for the frequent biphenotypism seen in erythroid and megakaryocytic malignancies. The lineage plasticity commonly seen in these malignancies thus recapitulates features of normal human erythroblasts and is not simply an effect of leukemogenesis. The molecular basis for this lineage plasticity may reside in the extensive overlap in transcription factors that program erythroid and megakaryocytic development. In particular, GATA-1 and NF-E2 each can dominantly reprogram myeloid cells into both erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages. 20-22 Knockout mice lacking either of these transcription factors manifest combined abnormalities in erythroid and megakaryocytic development. 23,24 Emerging data suggest that signal transduction via protein kinase C (PKC) may determine whether GATA-1 functions as an erythroid or megakaryocytic transcription factor. 25,26 The PKC-ε isozyme seems to be of particular importance in programming megakaryocytic differentiation. 26 Thus subtle changes in intracellular signaling and in the balance of transcription factors may be capable of inducing a dramatic lineage switch from erythroid to megakaryocytic phenotypes.

The activitie(s) in the conditioned medium that elicit this lineage switch remain unknown. Preliminary studies have indicated a resistance both to heat treatment and to treatment with pronase beads (data not shown), suggesting involvement of nonprotein mediator(s). Of potential relevance are recent reports documenting the production of bioactive arachidonic acid metabolites during megakaryocytic differentiation and the ability of some of these metabolites to activate PKC-ε signaling. 27,28

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. James Mandell for advice on immunofluorescent staining; Mr. Ron Pace of the University of Virginia Markey Center for valuable assistance with fluorescence microscopy; and Drs. Paul Bray and Paul O’Donnel for assistance with CD34+ cells.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Adam N. Goldfarb, M.D., Department of Pathology, University of Virginia Health Sciences Center, HSC Box 800214, Charlottesville, VA 22908. E-mail: ang3x@virginia.edu.

Supported by Public Health Service grant CA-72704 from the National Cancer Institute (to A. N. G.) and Public Health Service grant HL-04017 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (to F. K. R.).

References

- 1.Brunning RD, McKenna RW: Acute myeloid leukemias: tumors of the bone marrow. Atlas of Tumor Pathology, ed 1, vol 9. Washington, DC, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1994, pp 22–100

- 2.Debili N, Kieffer N, Mitjavila MT, Villeval JL, Guichard J, Teillet F, Henri A, Clemetson KJ, Vainchenker W, Breton-Gorius J: Expression of platelet glycoproteins by erythroid blasts in four cases of trisomy 21. Leukemia 1989, 3:669-678 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Linari S, Vannucchi AM, Ciolli S, Leoni F, Caporale R, Grossi A, Pagliai G, Santini V, Paoletti F, Ferrini PR: Coexpression of erythroid and megakaryocytic genes in acute erythroblastic (FAB M6) and megakaryoblastic (FAB M7) leukaemias. Br J Haematol 1998, 102:1335-1337 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alitalo R: Induced differentiation of K562 leukemia cells: a model for studies of gene expression in early megakaryoblasts. Leuk Res 1990, 14:501-514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long MW, Heffner CH, Williams JL, Peters C, Prochownik EV: Regulation of megakaryocyte potential in human erythroleukemic cells. J Clin Invest 1990, 85:1072-1084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hocevar BA, Morrow DM, Tykocinski ML, Fields AP: Protein kinase C isotypes in human erythroleukemia cell proliferation and differentiation. J Cell Sci 1992, 101:671-679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morrow DM, Xiong N, Getty RR, Ratajczak MZ, Morgan D, Seppala M, Riittinen L, Gewirtz AM, Tykocinski ML: Hematopoietic placental protein 14. An immunosuppressive factor in cells of the megakaryocytic lineage. Am J Pathol 1994, 145:1485-1495 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debili N, Coulombel L, Croisille L, Katz A, Guichard J, Breton-Gorius J, Vainchenker W: Characterization of a bipotent erythro-megakaryocytic progenitor in human bone marrow. Blood 1996, 88:1284-1296 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Southcott MJG, Tanner MJA, Anstee DJ: The expression of human blood group antigens during erythropoiesis in a cell culture system. Blood 1999, 93:4425-4435 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Metcalf D: Lineage commitment and maturation in hematopoietic cells: the case for extrinsic regulation. Blood 1998, 92:345-348 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Enver T, Heyworth CM, Dexter TM: Do stem cells play dice? Blood 1998, 92:348-351 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Racke FR, Lewandowska K, Goueli S, Goldfarb AN: Sustained activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase/mitogen-activated protein kinase is required for megakaryocytic differentiation of K562 cells. J Biol Chem 1997, 272:23366-23370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goncalves F, Lacout C, Villeval J-L, Wendling F, Vainchenker W, Dumenil D: Thrombopoietin does not induce lineage-restricted commitment of Mpl-R expressing pluripotent progenitors but permits their complete erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation. Blood 1997, 89:3544-3553 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stoffel R, Ziegler S, Ghilardi N, Ledermann B, De Sauvage FJ, Skoda RC: Permissive role of thrombopoietin and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor receptors in hematopoietic cell fate decisions in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1999, 96:698-702 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki R, Ogata H, Iguchi T, Sogo S, Kushida T, Ito T, Inaba M, Ikehara S, Kobayashi Y: Comparative analysis of megakaryocytes derived from cord blood and bone marrow. Br J Haematol 2000, 108:602-609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawai N, Koike K, Ito S, Kurokawa Y, Mwamtemi HH, Kinoshita T, Sakashita K, Higuchi T, Takeuchi K, Shiohara M, Ogami K, Komiyama A: Apoptosis of erythroid precursors under stimulation with thrombopoietin: contribution to megakaryocytic lineage choice. Stem Cells 1999, 17:45-53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lumelsky NL, Schwartz BS: Protein kinase C in erythroid and megakaryocytic differentiation: possible role in lineage determination. Biochim Biophys Acta 1997, 1358:79-92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vannucchi AM, Paoletti F, Linari S, Cellai C, Caporale R, Ferrini PR, Sanchez M, Migliaccio G, Migliaccio AR: Identification and characterization of a bipotent (erythroid and megakaryocytic) cell precursor from the spleen of phenylhydrazine-treated mice. Blood 2000, 95:2559-2568 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Basch RS, Zhang X-M, Dolzhansky A, Karpatkin S: Expression of CD41 and c-mpl does not indicate commitment to the megakaryocyte lineage during haemopoetic development. Br J Haematol 1999, 105:1044-1054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Visvader JE, Crossley M, Hill J, Orkin SH, Adams JM: The C-terminal zinc finger of GATA-1 or GATA-2 is sufficient to induce megakaryocytic differentiation of an early myeloid cell line. Mol Cell Biol 1995, 15:634-641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seshasayee D, Gaines P, Wojchowski DM: GATA-1 dominantly activates a program of erythroid gene expression in factor-dependent myeloid FDCW2 cells. Mol Cell Biol 1998, 18:3278-3288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamaguchi Y, Zon LI, Ackerman SJ, Yamamoto M, Suda T: Forced GATA-1 expression in the murine myeloid cell line M1: induction of c-Mpl expression and megakaryocytic/erythroid differentiation. Blood 1998, 91:450-457 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shivdasani RA, Rosenblatt MF, Zucker-Franklin D, Jackson CW, Hunt P, Saris C, Orkin SH: Transcription factor NF-E2 is required for platelet formation independent of the actions of thrombopoietin/MGDF in megakaryocyte development. Cell 1995, 81:695-704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shivdasani RA, Fujiwara Y, McDevitt MA, Orkin SH: A lineage-selective knockout establishes the critical role of transcription factor GATA-1 in megakaryocytic growth and platelet development. EMBO J 1997, 16:3965-3973 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Myklebust JH, Smeland EB, Josefsen D, Sioud M: Protein kinase C-α isoform is involved in erythropoietin-induced erythroid differentiation of CD34+ progenitor cells from human bone marrow. Blood 2000, 95:510-518 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Racke FK, Wang D, Zaidi Z, Kelley J, Visvader J, Soh J-W, Goldfarb AN: A potential role for protein kinase C-ε in regulating megakaryocytic lineage commitment. J Biol Chem 2001, 276:522-528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheppard K-A, Greenberg SM, Funk CD, Romano M, Serhan CN: Lipoxin generation by human megakaryocyte-induced 12-lipoxygenase. Biochim Biophys Acta 1992, 1133:223-234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chun J, Auer KA, Jacobson BS: Arachidonate initiated protein kinase C activation regulates HeLa cell spreading on a gelatin substrate by inducing F-actin formation and exocytic upregulation of β1 integrin. J Cell Physiol 1997, 173:361-370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]