Abstract

Cast nephropathy, or myeloma kidney, is a potentially reversible cause of chronic renal failure. In this condition, filtered light chains bind to a common site on Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP), which is produced by cells of the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. Subsequent aggregation of these proteins produces casts that obstruct tubule fluid flow and results in renal failure. In the present study, we used the yeast two-hybrid system to determine the site of interaction of light chains with THP. The third complementarity-determining region (CDR3) of both κ and λ light chains interacted with THP. These findings were confirmed in a series of competition studies using a synthetic peptide that corresponded to the CDR3 region and purified THP and light chains. Variations in the CDR3 sequence of the light chain affected binding. Thus, the current studies increase our understanding of the process of cast formation and provide an opportunity to develop strategies that may inhibit this interaction and prevent the clinical manifestations of myeloma kidney.

More than 150 years ago, an astute clinician, Dr. William Macintyre, found an abnormal substance in the urine of one of his patients. He sent the material to Dr. Henry Bence Jones, who reported the newly described protein and the association with multiple myeloma. 1 Bence Jones proteins were subsequently identified as immunoglobulin light chains. 2 Light chains are typically filtered from the blood by the kidney and metabolized similarly to other low molecular weight proteins. 3 However, these proteins can be nephrotoxic. 4 During the process of absorption and catabolism, light chains have been shown to cause proximal tubular epithelial cell injury. 4,5 When the reabsorptive capacity of the proximal tubular cells is saturated, light chains are presented to the distal nephron, where they form casts that obstruct flow of tubular fluid. The resultant renal failure is known clinically as cast nephropathy, or myeloma kidney. 6

Cast nephropathy represents the most common cause of renal failure in multiple myeloma. 7 To initiate cast formation, light chains bind to a specific peptide domain on Tamm-Horsfall protein (THP), 8-12 which is synthesized exclusively by cells of the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. 13,14 Co-aggregation of light chains with THP produces the intraluminal casts that are the prominent feature of myeloma kidney. 8 The electrolyte composition of the tubule fluid as well as tubule fluid flow rates and amount of THP 8-12 modulate binding. The structure of the light chain plays an important role in association with THP 10 and may also promote homotypic aggregation. 15 Although myeloma kidney is potentially reversible, prevention of cast formation is the key to controlling the problem. Understanding the protein interactions involved in cast formation represents the initial advance in development of potential treatment strategies designed to prevent myeloma kidney. The current study determined the domain on the light chain involved in binding THP.

Materials and Methods

Yeast Two-Hybrid Studies

The yeast two-hybrid system (Matchmaker LexA Two-Hybrid System; Clontech Lab. Inc., Palo Alto, CA) was used initially to detect binding interactions between THP and immunoglobulin light chains. This approach was similar to the original description of the yeast two-hybrid assay, 16 but was a LexA-based interaction trap system. 17 The host strain in these experiments was Saccharomyces cerevisiae EGY48[p8op-lacZ]. The bait consisted of two fragments of human THP that were obtained by polymerase chain reaction using cDNA that was provided by Genentech, Inc. (South San Francisco, CA). Description of the cloning and characterization of THP has been published. 18 All primers used in this study were obtained commercially (Operon Tech. Inc., Alameda, CA). Because there is a single binding domain (amino acid residues 225 to 233) for light chains on THP, 10,12 the present study used two fragments of THP that contained this domain. A 787-bp fragment (encoding amino acid residues 148 to 410, termed THP787) was polymerase chain reaction-amplified using 5′-CCGGAATTCCAATGTGGTGGGCAGCTACTT-G-3′ as the forward primer and 5′-ACGCTCGAGCTCCACGGAGCTGGGGTCTGTGC-3′ as the reverse primer. Underlined sequences in the upstream and downstream primers contained an EcoRI and XhoI site, respectively. A 248-bp fragment (encoding amino acid residues 188 to 270, termed THP248) was created using 5′-CCGGAATTCCGCATGGCCGAGACCTGCGTGC as the forward primer and 5′-ACGCTCGAGCTCCACGGAGCTGGGGTCTGTGC3′ as the reverse primer. THP787 and THP248 were each ligated into pBluescript II SK(−) vector (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using EcoRI and XhoI and then cloned. Sequences of both products were confirmed using a kit (T7 Sequenase DNA sequencing kit; Amersham Life Science, Inc., Cleveland, OH). THP787 and THP248 were then cloned into the pLexA expression vector using EcoRI and XhoI.

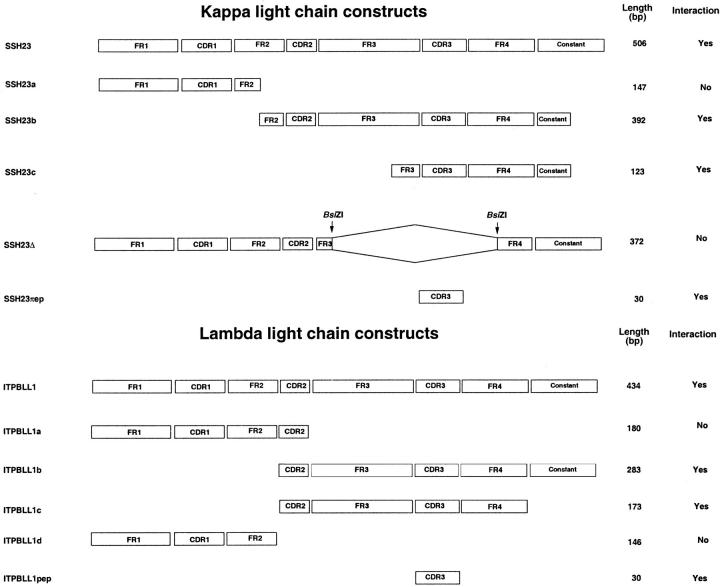

Representative cDNAs encoding immunoglobulin κ and λ light chains were generous gifts from Dr. S. Louis Bridges, Jr., at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL. A total of four unique κ and seven λ light chains were used. Descriptions of these molecules have been published. 19-21 Each cDNA was used as a template in polymerase chain reactions to generate fragments that were initially cloned into pBluescript II SK(−) for sequencing and then inserted in-frame into pB42AD expression vector, using EcoRI and XhoI. The expressed fusion proteins consisted of the light chain of interest and the LexA transcriptional activation domain. Primers and light chains used in these reactions were shown in Tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ . A series of truncation and deletion mutants of the κ light chain, SSH23, and the λ light chain, ITPBLL1, were also created (Figure 1) ▶ . Restricting the 506-bp fragment with BsiZI that cut the insert in two unique sites, and subsequently purifying and intramolecularly re-ligating the product created a truncation mutant of SSH23. To generate the SSH23pep construct, two 5′-phosphorylated synthetic oligonucleotides, 5′-CCGGAATTCATGCAAGGTACACACTGGCCTCCGCTCACTCTCGAGCGT-3 ′and 5′-ACGCTCGAGAGTGAGCGGAGGCCAGTGTGTACCTTGCATGAATTCCGG-3′, were annealed and ligated into pBluescript II SK(−) for sequencing and then into pLexA, using EcoRI and XhoI. This sequence encoded a 10-amino acid peptide (MQGTHWPPLT) that corresponded to the amino acid residues from 94 to 103 on SSH23. ITPBLL1pep, which encoded a 10 amino acid peptide (QVWDSTSDHY) that corresponded to amino acid residues 88 to 97 of ITPBLL1, was prepared in similar manner using 5′-phosphorylated 5′-CCGGAATTCCAGGTATGGGATAGTACTAGTGATCATTATCTCGA-GCGT-3′ and 5′-ACGCTCGAGATAATGATCACTAGTACTATCCCATACCTGGAATTCCGG-3′. Both SSH23pep and ITPBLL1pep corresponded to the complementarity-determining region (CDR)3 of light chains. Automated DNA sequencing confirmed proper construction of all plasmids and authenticity of the sequences.

Table 1.

Primers Used to Generate the κ Light Chain Constructs

| Light chain construct, κ | Primer name | Forward and reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| ITPBL5 | LB62 | 5′-CCGGAATTCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCTCCA-3′ |

| H170 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ | |

| ITPBL11 | LB62 | 5′-CCGGAATTCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCTCCA-3′ |

| H170 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ | |

| BC Syn9 | LB62 | 5′-CCGGAATTCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCTCCA-3′ |

| H170 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ | |

| SSH23 | LB62 | 5′-CCGGAATTCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCTCCA-3′ |

| LSK19 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ | |

| SSH23a | LB62 | 5′-CCGGAATTCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCTCCA-3′ |

| SSH23a | 5′-ACGCTCGAGTGGAGATTGGCCTGGCCT-3′ | |

| SSH23b | SSH23b | 5′-CCGGAATTCAGGCGCCTAATTTATAAG-3′ |

| H170 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ | |

| SSH23c | SSH23c | 5′-CCGGAATTCTATTACTGCATGCAA-3′ |

| H170 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ | |

| SSH23Δ | LB62 | 5′-CCGGAATTCGAAATTGTGTTGACGCAGTCTCCA-3′ |

| LSK19 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGAACTGCTCATCAGATGGCGGGAAG-3′ |

Underlined sequences contained EcoRI and Xho I restriction sites on the forward and reverse primers, respectively.

Table 2.

Primers Used to Generate the λ Light Chain Constructs

| Light chain construct, λ | Primer name | Forward and reverse primers |

|---|---|---|

| ITPBLL1 | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL1a | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| PBLL1a | 5′-ACGCTCGAGTCGCTCAGGGATCTCTGA-3′ | |

| ITPBLL1b | PBLL1b | 5′-CCGGAATTCAGCGACCGGCCCTCAGAG-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL1c | PBLL1b | 5′-CCGGAATTCAGCGACCGGCCCTCAGAG-3′ |

| PBLL1c | 5′-ACGCTCGAGTAGGACGGTGACCTT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL1d | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| PBLL1d | 5′-ACGCTCGAGATAGACGACCAGCAC-3′ | |

| LKPBLLL2 | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL11 | LB76 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCTGCACAGTCTCTGAGGCC-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL22 | LB77 | 5′-CCGGAATTCCCCTGAATTCCTCGGCGTCCTTGCTTACTGCA-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL68 | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL7 | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ | |

| ITPBLL75 | LB75 | 5′-CCGGAATTCTCCGAATTCTCCTCTCTCACTGCACAG-3′ |

| LB69 | 5′-ACGCTCGAGGGGAATTCGCTCCCGGGTAGAAGTCTCT-3′ |

Underlined sequences contained Eco RI and Xho I restriction sites on the forward and reverse primers, respectively.

Figure 1.

To determine the THP-binding domain on light chains, a series of mutants of κ (SSH23) and λ (ITPBLL1) light chains was examined. The four framework regions (FR) and three CDRs of the variable subunit of the light chains are shown. The lengths (in bp) of the constructs and interaction of the fusion proteins with THP are displayed.

EGY48[p8op-lacZ] yeast were co-transformed with pLexA-THP787 (or pLexA-THP248) and pB42AD-light chain construct, using the lithium acetate method (Alkali-Cation yeast transformation kit; BIO101 Inc., La Jolla, CA). EGY48[p8op-lacZ] yeast were also co-transformed with plasmids (pLexA-Pos alone and pLexA-53/pB42AD-T) that served as positive control experiments and with plasmids (pLexA-Lam/pB42AD-T) that served as a negative control. The pLexA-Pos plasmid encoded a fusion of the DNA-binding domain (LexA) with the GAL4-activating domain, allowing activation of genes under control of LexA operators (LEU2 and lacZ). pLexA-53 and pB42AD-T provided another positive control experiments by encoding proteins known to interact (murine p53 and SV40 large T-antigen, respectively). pLexA-Lam encoded a fusion of the DNA-binding domain with human lamin C that does not interact with SV40 large T antigen and thus served as a negative control. Double transformants were selected in a standard manner using medium that lacked histidine and tryptophan. The transformants were incubated at 30°C for 4 days. Interactions between the two hybrid proteins were then tested by growth in galactose-containing, leucine-deficient medium and by β-galactosidase plate and liquid culture assays. In the in vivo plate assay, 200 to 400 cfu of transformed yeast were dispersed on to 100-mm agar plates containing 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl-β-d-galactopyranoside (X-Gal, 80 mg/L), 1× BU salts (26 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 25 mmol/L Na2HPO4, pH 7), and either 2% galactose or 2% dextrose. The plates were incubated at 30°C for 3 to 6 days to generate the blue color. The interactions were further quantified by liquid culture assay of β-galactosidase activity using o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside (Amersham Life Science, Inc., Cleveland, OH) as the substrate. Using other proteins, relative affinities detected with this reaction have been shown to correlate with interactions detected using other biochemical methods. 22 Five separate transformants were each examined in triplicate. Reactions were performed at 30°C in solutions containing 60 mmol/L Na2HPO4, 40 mmol/L NaH2PO4, 10 mmol/L KCl, 1 mmol/L MgSO4, and 50 mmol/L β-mercaptoethanol. Timing of the reaction began as o-nitrophenyl β-d-galactopyranoside was added and the reaction continued until a yellow color was observed. The reaction mixture was then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 minutes to pellet cell debris. Absorbance of the supernatant at 420 and 600 nm was determined. Units of β-galactosidase activity were calculated as follows: units = [1,000*OD400]/[(elapsed time)*(0.1*concentration factor)*OD600].

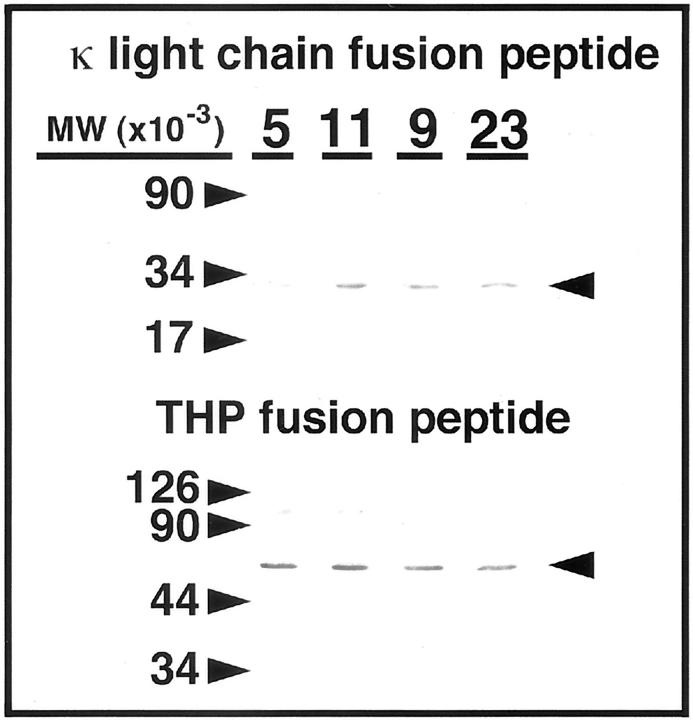

To verify expression of the fusion proteins, selected samples were examined using Western blotting. Yeast cells were pelleted, then resuspended in cracking buffer, 8 mol/L urea, 5% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 40 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 0.1 mmol/L ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 0.08% β-mercaptoethanol and a combination of protease inhibitors (Complete; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) was included. The yeast were disrupted by vigorous shaking for 3 minutes at 5,000 rpm (MiniBeadbeater; Biospec Products Co., Bartlesville, OK) after addition of 425 to 600 μmol/L glass beads (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO). Cell debris was removed by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm for 5 minutes at 4°C. Western blot detection of THP and light chains then proceeded in standard manner. 23,24 Briefly, the supernatant fractions were boiled briefly, then separated using 8 or 12% polyacrylamide gels and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then probed using rabbit anti-human THP antiserum (Biomedical Technologies, Inc., Stoughton, MA) or rabbit anti-human Ig/L-chain type lambda and type kappa (Behringwerke AG, Marburg, Germany).

Purification of Human THP and Immunoglobulin Light Chains

Human THP and light chains were obtained from urine in standard manner. 8-12 THP was purified from urine of a healthy adult male by precipitation in 0.64 mol/L NaCl, followed by dialysis and lyophilization. Purified human THP was biotinylated as described previously, 25 using sulfo-N-hydroxysuccinimide biotin (ImmunoPure Sulfo-NHS-Biotin; Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), followed by dialysis against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 4°C for 24 hours to remove free biotin. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis identified a single band at ∼100 kd (data not shown). Six different light chains (three κ and three λ) were also used in this study and were obtained from patients who had light chain proteinuria and clinical renal failure. The patients who donated λ2 and λ5 had biopsy-proven cast nephropathy. Patients who donated λ5, κ3, and κ7 had clinical presentations that were compatible with cast nephropathy, but did not undergo kidney biopsy. The patient who donated κ6 had Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia and progressive renal failure and was also not biopsied. These light chains were purified from urine by precipitation using 70% ammonium sulfate, followed by ion-exchange chromatography. 4,5,8,9 Purified light chains were dialyzed and lyophilized. A single band at ∼22 kd was identified by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (data not shown). Proteins were kept at −20°C until use.

Peptide Competition Experiments

A synthetic peptide was obtained commercially (Research Genetics Inc., Huntsville, AL). MQGTHWPPLT corresponded to the CDR3 region of SSH23. Peptides were purified by high-pressure liquid chromatography; the molecular masses were confirmed by mass spectrometry.

Competition experiments were performed using solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and Western and dot blotting. To perform enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, wells of microtiter plates were coated with each of the six purified light chains, 0.2 mmol/L in PBS, and incubated overnight at room temperature. Biotinylated human THP, 0.2 μmol/L, was incubated overnight at 4°C alone or with the CDR3 peptide. The concentration of the peptides ranged from 0 to 4 mmol/L. After washing the wells with 0.05% Tween 20 in PBS and blocking with 1% bovine serum albumin in PBS, the pre-incubated, THP/peptide mixtures were added to the wells and incubated at 37°C for 2 hours. After washing, samples were incubated with avidin conjugated with horseradish peroxidase (ImmunoPure avidin, horseradish peroxidase conjugated; Pierce Chemical Co., Rockford, IL), 1:2,000 dilution in PBS. After additional washes, wells were developed using Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzthiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) as substrate in citrate-phosphate buffer, pH 4.2. Optical density was determined at 405 nm using a microplate reader (VERSAmax; Molecular Devices Corp., Menlo Pack, CA).

In other competition experiments, 10 μg samples of each of the six light chains were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis using 12% polyacrylamide gels and then transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. Twenty μg of yeast extract containing the fusion proteins were dot-blotted directly onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking and washing, the blots were probed with 0.2 μmol/L biotinylated THP or 0.2 μmol/L biotinylated THP that had been pre-incubated with CDR3 peptide, 4 mmol/L, overnight at 4°C. After additional washes, the membranes were incubated with streptavidin-conjugated HRP, 1:10,000 dilution in Tris-buffered saline. The membranes were developed using ECL Western blotting system and Hyperfilm (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ).

Statistical Analysis

All data were presented as mean ± SE. Significant differences were determined using one-way analysis of variance with standard post hoc testing (Statview, version 5.0; SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC). A P value of < 0.05 assigned statistical significance.

Results

Human THP Interacted with Human Light Chains in Vivo

Initial experiments ensured that the hybrid proteins that consisted of the pLexA DNA-binding domain and the two fragments of human THP did not, by themselves, trans-activate the reporter genes. Both peptide segments of THP contained the known single binding site for light chains. 10,12 The light chain constructs that were tested are shown in Tables 1 and 2 ▶ ▶ . Western analysis of extracts of representative co-transformed yeast confirmed expression of fusion proteins that contained THP and light chain (Figure 1) ▶ . When co-expressed with pLexA-THP248 and pLexA-THP787, fusion proteins that consisted of the LexA activation domain and both κ and λ light chains activated both LEU2 and lacZ reporter genes. Reporter gene activity was strictly galactose-dependent. There were no interactions among any of the light chain constructs and pLexA-Lam, which encoded human lamin C protein. Also, transformation of yeast with pB42AD-T, which encoded the SSV40 large T-antigen, and either pLexA-THP248 or pLexA-THP787 did not activate either reporter gene. Interactions were further quantified using a liquid culture assay of β-galactosidase activity (Table 3) ▶ . Although all of the light chains interacted with THP, the relative strength of the interactions differed among the 11 light chains examined. The λVI light chain, ITPBLL75, showed a low-affinity interaction: yeast transformed with this construct grew slowly in leucine-deficient medium and possessed low β-galactosidase activity. The λIIIa light chain, ITPBLL1, demonstrated the highest binding affinity among the light chains tested.

Table 3.

Summary of the Interactions between the Two THP Fusion Proteins with the Light Chain Proteins

| Light chain | Isotype | Size (bp) | Interaction with THP β-galactosidase activity (units) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 248-bp fragment | 787-bp fragment | |||

| κ | ||||

| ITPBL5 | κI | 480 | 4.0 ± 0.1 | 4.3 ± 0.4 |

| ITPBL11 | κII | 465 | 3.4 ± 0.5 | 5.4 ± 0.6 |

| BC Syn9 | κIV | 462 | 3.2 ± 0.2 | 4.4 ± 0.3 |

| SSH23 | κII | 506 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 5.6 ± 0.1 |

| SSH23a | 147 | NI | NI | |

| SSH23b | 392 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | 5.8 ± 0.2 | |

| SSH23c | 123 | 5.7 ± 0.2 | 5.4 ± 0.1 | |

| SSH23Δ | 372 | NI | NI | |

| SSH23pep | 30 | 5.8 ± 0.4 | 5.8 ± 0.8 | |

| λ | ||||

| ITPBLL1 | λIIIa | 434 | 7.1 ± 0.1 | 7.5 ± 0.8 |

| ITPBLL1a | 180 | NI | NI | |

| ITPBLL1b | 283 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 14.1 ± 1.1 | |

| ITPLL1c | 173 | 5.1 ± 0.3 | 6.7 ± 0.3 | |

| ITPBLL1d | 146 | NI | NI | |

| ITPBLL1pep | 30 | 7.5 ± 0.6 | 6.2 ± 1.0 | |

| LKPBLLL2 | λI | 442 | 4.0 ± 0.2 | 3.5 ± 0.5 |

| ITPBLL11 | λIIIb | 430 | 4.8 ± 0.7 | 4.1 ± 0.5 |

| ITPBLL22 | λIIIc | 426 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 6.8 ± 1.3 |

| ITPBLL68 | λIV | 441 | 4.5 ± 0.4 | 3.5 ± 0.6 |

| ITPBLL7 | λV | 454 | 3.6 ± 0.5 | 3.9 ± 0.4 |

| ITPBLL75 | λVI | 431 | 2.2 ± 0.2 | 2.5 ± 0.1 |

All interactions were galactose-specific. NI, no interaction.

The CDR3 Domain of the Variable Region of the Light Chain Interacted with THP

To identify the domain on the light chain that interacted with THP, a series of truncated constructs of SSH23 and ITPBLL1 (Figure 2) ▶ were tested for binding to the THP fragments in vivo. Deletion of the N-terminal portions of the variable regions of both SSH23 and ITPBLL1 did not abolish interaction with THP. Removal of the constant homology domains of the light chains also did not alter binding. In contrast, SSH23Δ, which lacked a portion of the third and fourth framework regions and the CDR3 region, did not interact with THP. The two 10-amino acid peptide sequences that represented the CDR3 portions of both molecules interacted with THP in vivo.

Figure 2.

Western blots of cytoplasmic extracts of yeast co-expressing fusion proteins that consisted of the pLexA DNA-binding domain and a fragment of human THP and the LexA activation domain fused to κ light chains. Top: The yeast expressed the κ light chain/LexA activation domain proteins (ITPBL5, ITPBL11, BC Syn 9, and SSH23). Bottom: Expression of the THP/pLexA DNA-binding domain fusion protein. The expected contribution of the κ light chain and THP fragments to each of the fusion proteins was ∼23 kd and 29 kd, respectively.

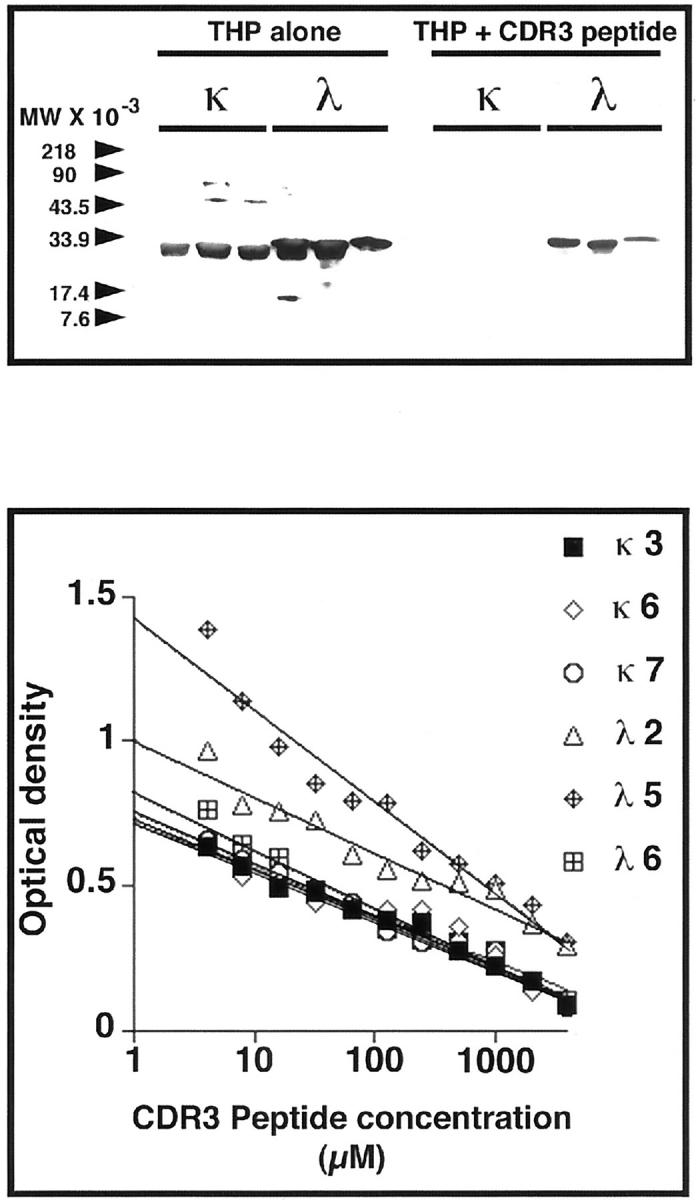

A Synthetic Peptide Corresponding to the CDR3 Domain Inhibited Binding of Light Chains to THP

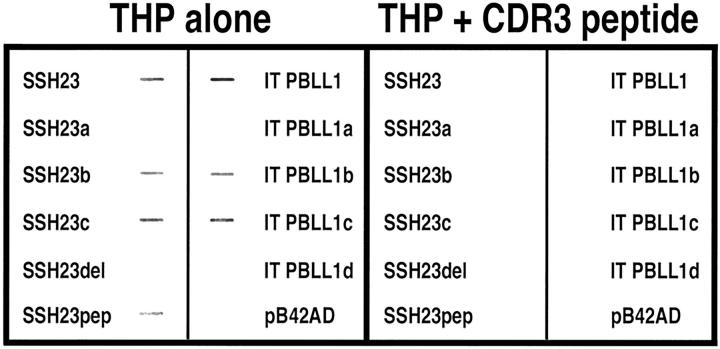

Biotinylated human THP bound to six different light chains, three κ and three λ, which had been purified from patients who had renal failure and light chain proteinuria. Pre-incubation of the THP with a synthetic 10-amino acid peptide that represented the CDR3 region of SSH23 effectively inhibited interaction of THP with the bound light chains (Figure 3) ▶ . Using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, this peptide inhibited, in a dose-response manner, binding of THP to these light chains (Figure 3) ▶ . Extracts from yeast that had been transformed with the various light chain constructs were dot blotted and then incubated with biotinylated THP to show binding (Figure 4) ▶ . As anticipated from the in vivo studies, THP bound to samples that contained SSH23, SSH23b, SSH23c, and SSH23pep, but did not interact with samples containing SSH23a and SSH23Δ. THP also bound to samples that contained ITPBLL1, ITPBLL1b, and ITPBLL1c, but not extracts from yeast that expressed ITPBLL1a and ITPBLL1d. These findings confirmed the in vivo studies described above. Pre-incubation of THP with the CDR3 peptide resulted in inhibition of binding to these samples.

Figure 3.

Top: Biotinylated human THP binds to six different human light chains purified from the urine of patients with renal failure and multiple myeloma. Pre-incubation of THP (0.2 μmol/L) with the CDR3 peptide, MQGTHWPPLT (4 mmol/L), which corresponded to the CDR3 region of SSH23, inhibited binding to the light chains. Bottom: The dose-response effect of this peptide on inhibiting binding of THP to these same light chains bound to microtiter wells. An inhibitory effect was observed even at the lowest concentration (4 μmol/L) of peptide.

Figure 4.

Biotinylated human THP binds to samples of extracts from yeast expressing the various light chain fusion proteins (left). As anticipated from the in vivo studies, biotinylated THP bound to samples containing SSH23, SSH23b, SSH23c, SSH23pep, ITPBLL1, ITPBLL1b, and ITPBLL1c. Binding was inhibited by pre-incubation of the THP, 0.2 μmol/L, with the CDR3 peptide, MQGTHWPPLT, 4 mmol/L (right). Both gels were produced simultaneously and developed using the same film and developing solution.

Discussion

Cast nephropathy is a form of progressive renal failure that occurs in the setting of multiple myeloma. Although it was well known that immunoglobulin light chains participate integrally in the process, 26-30 dissecting the pathogenesis of this complex problem proved difficult. More recently, evidence demonstrated an important role of THP in cast nephropathy. 8-12 Using immunofluorescence microscopy, THP has been shown to be a component of the casts. 31 THP, a protein that is synthesized by cells of the thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle, 13,14 exists in the kidney both in soluble form and attached to the outer leaflet of the apical plasma membrane by a phosphatidylinositol (GPI) anchor. 18,32 In an experimental model of cast nephropathy, this area of the nephron was also the initial site of cast formation. By altering production of THP, intranephronal obstruction from light chain precipitation was prevented. 9 Subsequent analysis of the THP interaction with light chains demonstrated a single binding site on THP. 12 The resultant aggregation of these proteins produced intraluminal obstruction from cast formation. 9 The present studies used the yeast two-hybrid system, which has been successfully used to identify biologically important protein-protein interactions, 17,22,33-37 to clarify the interaction of THP with light chains. The THP-binding site on both κ and λ light chains was the CDR3 region in the variable domain of the molecules. The yeast two-hybrid findings were confirmed by showing a synthetic peptide that corresponded to the CDR3 region of SSH23 inhibited binding of THP to six different light chains from patients who had light chain proteinuria and clinical manifestations of renal failure. This peptide also inhibited binding of purified THP to the fusion proteins that were present in the yeast extracts (Figure 4) ▶ .

Every light chain contains two globular subunits that are termed variable and constant homology domains. 38 The variable domain consists of a series of four framework regions that form irregular β-pleated sheets that surround a tightly packed hydrophobic interior. 39,40 Three hypervariable segments, termed CDRs, configure part of the antigen-binding site on the immunoglobulin molecule. 38,41 The CDRs form loop structures and represent the regions of sequence variability among light chains. 42-44 Thus, although possessing similar structures, no two light chains are identical. The CDR3 region is perhaps the most variable portion of the molecule, in part because of V-J recombination and because of the capability of terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase to insert nongermline-encoded nucleotides in this region. 19,20,45 It is therefore interesting that CDR3 binds THP, although there are similarities in this region among many κ and λ light chains. Kabat and colleagues, 46 first identified the appearance of certain amino acid residues in CDRs of heavy and light chains. Mian and associates 47 suggested that amphipathic amino acids, especially tryptophan and tyrosine, are frequently present in CDR regions, because they permit flexibility to interact with a wide range of antigens. Thus, although required to promote antigen binding, these residues also allow cross-reactivity with other proteins. However, the relative affinities of the light chains for THP varied, with one of the λ light chains, ITPBLL75, in the present study showing very low affinity. The Kyte-Doolittle hydropathy plot of the CDR3 region of ITPBLL75 differed from the plots of SSH23 and ITPBLL1, which were light chains that showed higher binding affinities for THP. Thus, the entire domain appeared to modulate the interaction.

In summary, the identification of the CDR3 region as the single binding site of light chains for THP provides new insights into the pathogenesis of cast nephropathy related to multiple myeloma. Differences in the CDR3 region accounts for the variable affinity of light chains for THP, when this process is examined under controlled conditions. Our previous studies, using a rodent model of in vivo cast formation, showed that binding of light chain to THP was required for cast formation. 8,9,48 However, other factors modulate this interaction and determine the clinical expression of the disease. 9-11 For example, a light chain from a patient who had no clinically evident renal dysfunction bound THP in vitro, albeit at lower affinity. This same light chain did not obstruct the lumen of perfused nephrons of euvolemic rats, but did obstruct nephrons of hydropenic rats. 9 Thus, although there is only a general correlation between binding affinity and clinical cast nephropathy, all tested light chains that potentially form casts in vivo also bind THP. 8-12,48 Certainly, not all light chains are nephrotoxic. Some patients excrete gram’s of light chains in the urine and yet do not manifest renal injury clinically. 49 The present study demonstrated that the amino acid sequence of the CDR3 region, along with other factors previously reported, 8-12 modulates the binding of THP to light chains and subsequent development of clinical manifestations of renal failure. Finally, because the basic mechanism of this process was elucidated, these studies have provided an opportunity to pursue strategies that inhibit this interaction and potentially prevent the severe renal failure that occurs in this setting.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gordon N. Gill, M.D., (the University of California, San Diego) for his intellectual support, and Ms. Karen Lewis for excellent technical assistance.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Paul W. Sanders, M.D., Division of Nephrology/Department of Medicine, 642 Lyons-Harrison Research Building, 701 South 19th St., University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL 35294-0007. E-mail: psanders@uab.edu.

Supported by The Office of Research and Development, Medical Research Service, Department of Veterans Affairs, and National Institutes of Health grant (R01 DK46199).

References

- 1.Jones HB: Papers on chemical pathology: prefaced by the Gulstonian Lectures, read at the Royal College of Physicians, 1846. Lancet 1847, 2:88-92 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Edelman GM, Gally JA: The nature of Bence-Jones proteins: chemical similarities to polypeptide chains of myeloma globulins and normal γ-globulins. J Exp Med 1962, 116:207-227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baylis C, Falconer-Smith J, Ross B: Glomerular and tubular handling of differently charged human immunoglobulin light chains by the rat kidney. Clin Sci 1988, 74:639-644 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanders PW, Herrera GA, Chen A, Booker BB, Galla JH: Differential nephrotoxicity of low molecular weight proteins including Bence Jones proteins in the perfused rat nephron in vivo. J Clin Invest 1988, 82:2086-2096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sanders PW, Herrera GA, Galla JH: Human Bence Jones protein toxicity in rat proximal tubule epithelium in vivo. Kidney Int 1987, 32:851-861 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sanders PW: Myeloma kidney. Kidney 1993, 25:1-7 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iványi B: Frequency of light chain deposition nephropathy relative to renal amyloidosis and Bence Jones cast nephropathy in a necropsy study of patients with myeloma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1990, 114:986-987 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanders PW, Booker BB, Bishop JB, Cheung HC: Mechanisms of intranephronal proteinaceous cast formation by low molecular weight proteins. J Clin Invest 1990, 85:570-576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sanders PW, Booker BB: Pathobiology of cast nephropathy from human Bence Jones proteins. J Clin Invest 1992, 89:630-639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huang Z-Q, Kirk KA, Connelly KG, Sanders PW: Bence Jones proteins bind to a common peptide segment of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein to promote heterotypic aggregation. J Clin Invest 1993, 92:2975-2983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Huang Z-Q, Sanders PW: Biochemical interaction of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein with Ig light chains. Lab Invest 1995, 73:810-817 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang Z-Q, Sanders PW: Localization of a single binding site for immunoglobulin light chains on human Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein. J Clin Invest 1997, 99:732-736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoyer JR, Seiler MW: Pathophysiology of Tamm-Horsfall protein. Kidney Int 1979, 16:279-289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kumar S, Muchmore A: Tamm-Horsfall protein—uromodulin (1950–1990). Kidney Int 1990, 37:1395-1401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Myatt EA, Westholm FA, Weiss DT, Solomon A, Schiffer M, Stevens FJ: Pathogenic potential of human monoclonal immunoglobulin light chains: relationship of in vitro aggregation to in vivo organ deposition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1994, 91:3034-3038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fields S, Song O: A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature 1989, 340:245-246 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gyuris J, Golemis E, Chertkov H, Brent R: Cdi1, a human G1 and S phase protein phosphatase that associates with Cdk2. Cell 1993, 75:791-803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pennica D, Kohr WJ, Kuang W-J, Glaister D, Aggarwal BB, Chen EY, Goeddel DV: Identification of human uromodulin as the Tamm-Horsfall urinary glycoprotein. Science 1987, 236:83-88 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bridges SL, Jr: Frequent N addition and clonal relatedness among immunoglobulin lambda light chains expressed in rheumatoid arthritis synovia and PBL, and the influence of Vλ gene segment utilization on CDR3 length. Mol Med 1998, 4:525-553 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bridges SL, Jr, Lee SK, Johnson ML, Lavelle JC, Fowler PG, Koopman WJ, Schroeder HW, Jr: Somatic mutation and CDR3 lengths of immunoglobulin κ light chains expressed in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and in normal individuals. J Clin Invest 1995, 96:831-841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stüber F, Lee SK, Bridges SL, Jr, Koopman WJ, Schroeder HW, Jr, Gaskin F, Fu SM: A rheumatoid factor from a normal individual encoded by VH2 and VκII gene segments. Arth Rheum 1992, 35:900-904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Estojak J, Brent R, Golemis EA: Correlation of two-hybrid affinity data with in vitro measurements. Mol Cell Biol 1995, 15:5820-5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ying W-Z, Sanders PW: Expression of Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein is regulated by dietary salt in rats. Kidney Int 1998, 54:1150-1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ying W-Z, Sanders PW: Dietary salt increases endothelial nitric oxide synthase and TGF-β1 in rat aortic endothelium. Am J Physiol 1999, 277:H1293-H1298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen PY, St. John PL, Kirk KA, Abrahamson DR, Sanders PW: Hypertensive nephrosclerosis in the Dahl/Rapp rat: initial sites of injury and effect of dietary L-arginine administration. Lab Invest 1993, 68:174-184 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Koss MN, Pirani CL, Osserman EF: Experimental Bence Jones cast nephropathy. Lab Invest 1976, 34:579-591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Holland MD, Galla JH, Sanders PW, Luke RG: Effect of urinary pH and diatrizoate on Bence Jones protein nephrotoxicity in the rat. Kidney Int 1985, 27:46-50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smolens P, Venkatachalam M, Stein JH: Myeloma kidney cast nephropathy in a rat model of multiple myeloma. Kidney Int 1983, 24:192-204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smolens P, Barnes JL, Stein JH: Effect of chronic administration of different Bence Jones proteins on rat kidney. Kidney Int 1986, 30:874-882 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Solomon A, Weiss DT, Kattine AA: Nephrotoxic potential of Bence Jones proteins. N Engl J Med 1991, 324:1845-1851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Start DA, Silva FG, Davis LD, D’Agati V, Pirani CL: Myeloma cast nephropathy: immunohistochemical and lectin studies. Mod Pathol 1988, 1:336-347 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rindler MJ, Naik SS, Li N, Hoops TC, Peraldi M-N: Uromodulin (Tamm-Horsfall glycoprotein/uromucoid) is a phosphatidylinositol-linked membrane protein. J Biol Chem 1990, 265:20784-20789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iwabuchi K, Li B, Bartel P, Fields S: Use of the two-hybrid system to identify the domain of p53 involved in oligomerization. Oncogene 1993, 8:1693-1696 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu JY, Maniatis T: Specific interactions between proteins implicated in splice site selection and regulated alternative splicing. Cell 1993, 75:1061-1070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choi K-Y, Satterberg B, Lyons DM, Elion EA: Ste5 tethers multiple protein kinases in the MAP kinase cascade required for mating in S. cerevisiae. Cell 1994, 78:499-512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Golemis EA, Brent R: Fused protein domains inhibit DNA binding by LexA. Mol Cell Biol 1992, 12:3006-3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kurten RC, Cadena DL, Gill GN: Enhanced degradation of EGF receptors by a sorting nexin, SNX1. Science 1996, 272:1008-1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Solomon A: Light chains of immunoglobulins: structural-genetic correlates. Blood 1986, 68:603-610 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Poljak RJ, Amzel LM, Chen BL, Phizackerley RP, Saul F: The three-dimensional structure of the Fab′ fragment of a human myeloma immunoglobulin at 2.0-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1974, 71:3440-3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Padlan EA, Davies DR: Variability of three-dimensional structure of immunoglobulins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1975, 72:819-823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu TT, Kabat EA: An analysis of the sequences of the variable regions of Bence Jones proteins and myeloma light chains and their implications for antibody complementarity. J Exp Med 1970, 132:211-250 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chothia C, Lesk AM: Canonical structures for the hypervariable regions of immunoglobulins. J Mol Biol 1987, 196:901-917 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chothia C, Lesk AM, Tramontano A, Levitt M, Smith-Gill SJ, Air G, Sheriff S, Padlan EA, Davies D, Tulip WR, Colman PM, Spinelli S, Alzari PM, Poljak RJ: Conformations of immunoglobulin hypervariable regions. Nature 1989, 342:877-883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bruccoleri RE, Haber E, Novotny J: Structure of antibody hypervariable loops reproduced by a conformational search algorithm. Nature 1988, 335:564-568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Klein U, Küppers R, Rajewsky K: Human IgM+IgD+ B cells, the major B cell subset in the peripheral blood, express Vκ genes with no or little somatic mutation throughout life. Eur J Immunol 1993, 23:3272-3277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Bilofsky H: Unusual distributions of amino acids in complementarity-determining (hypervariable) segments of heavy and light chains of immunoglobulins and their possible roles in specificity of antibody-combining sites. J Biol Chem 1977, 252:6606-6616 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mian IS, Bradwell AR, Olson AJ: Structure, function and properties of antibody binding sites. J Mol Biol 1991, 217:133-151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sanders PW, Booker BB: Altered loop segment function is the initial event in precipitation of low molecular weight proteins in the rat nephron. Bianchi C Carone FA Rabkin R eds. Contributions to Nephrology, 1991, vol 83.:pp 100-103 Karger AG, Basel [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Woodruff R, Sweet B: Multiple myeloma with massive Bence Jones proteinuria and preservation of renal function. Aust NZ J Med 1977, 7:60-62 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]