Abstract

Carcinoid tumors are rare neuroendocrine tumors occurring in the lung or in the digestive tract where they are further subclassified as foregut, midgut, or hindgut carcinoids. To gain a better understanding of the genetic basis of the different types of carcinoid tumors, we have characterized numerical imbalances in a series of midgut carcinoids, and compared the results to previous findings in carcinoids from the lung. Numerical imbalances were revealed in 16 of the 18 tumors, and the most commonly detected aberrations were losses of 18q22-qter (67%), 11q22-q23 (33%), and 16q21-qter (22%), and gain of 4p14-qter (22%). The total number of alterations found in the metastases was significantly higher than in the primary tumors, indicating the accumulation of acquired genetic changes in the tumor progression. Losses of 18q and 11q were present both in primary tumors and metastases, whereas loss of 16q and gain of 4 were only detected in metastases. Furthermore, the pattern of comparative genomic hybridization alterations varied depending on the total number of detected alterations. Taken together, the findings would suggest a progression of numerical imbalances, in which loss of 18q and 11q represent early events, and loss of 16q and gain of 4p are late events in the tumor progression of midgut carcinoids. When compared to previously published comparative genomic hybridization abnormalities in lung carcinoids, loss of 11q was found to occur in both tumor types, whereas loss of 18q and 16q and gain of 4 were not revealed in lung carcinoids. The results indicate that inactivation of a putative tumor suppressor gene in 18q22-qter represents a frequent and early event that is specific for the development of midgut carcinoids.

Carcinoid tumors are rare neuroendocrine tumors, with an estimated incidence of 1 to 2 cases per 100,000 inhabitants based on cancer registries. 1 In a Swedish study, the incidence was 8.4, when calculated on the basis of both surgical specimens and autopsies. 2 The tumors most commonly occur in the lung or in the digestive tract and are further divided into foregut, midgut, or hindgut carcinoids according to their embryological origin. Foregut carcinoids usually occur in the lungs; midgut carcinoids are located in the small intestine, appendix, and proximal large bowel; and hindgut carcinoids develop in the distal colon and rectum. Out of the three types of carcinoids, the midgut forms are the most commonly encountered, with the majority of tumors located in the distal ileum or the appendix. Carcinoids located in the appendix typically have a benign biological behavior, in contrast to the more aggressive ileal carcinoids. The term midgut carcinoid usually refers to carcinoids located in the ileum. These patients frequently develop liver metastases, which in turn will give rise to the carcinoid syndrome characterized by symptoms of cutaneous flushing, bronchial constriction, episodic diarrhea, and right-sided cardiac valvular fibrosis. 3

The genetic mechanisms involved in the tumorigenesis of carcinoid tumors are poorly understood. The vast majority of cases are sporadic, although familial cancer syndromes associated with an increased risk of carcinoid tumors are also seen, mainly in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN 1). Most of the carcinoids associated with MEN 1 have been reported to be of foregut origin. 4 The gene responsible for MEN 1, MEN1 at 11q13, has recently been cloned and its involvement in the tumorigenesis of sporadic MEN 1-associated tumors has been characterized. 5,6 In carcinoids from the lung frequent somatic deletions of the MEN1 region have been demonstrated using loss of heterozygosity (LOH) and comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) analyses, 7-12 and in a significant proportion of the cases inactivating MEN1 mutations have also been detected. 8 Loss of 11q has also been characterized in a limited number of carcinoids, which were of ileal, duodenal, and gastric origin, 7,13 and on 18q in gastrointestinal carcinoids. 12

Other frequently detected genetic alterations in carcinoid tumors include losses of 3p, 5q, 9p, 10q, and 13q in lung carcinoids. 10,11 The TP53 gene, which is frequently mutated in most human tumors, including gastrointestinal tumors, 14 is only rarely mutated in carcinoids, 15,16 indicating that TP53 is not important in the tumorigenesis.

To gain a better understanding of the genetic basis of the different types of carcinoid tumors, we have characterized numerical imbalances in a series of midgut carcinoids using CGH, and compared the results to previous findings in carcinoids from the lung.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Specimens

The study includes 18 tumor specimens from 18 patients operated on for midgut carcinoids at the Karolinska Hospital between 1986 and 1997. The samples were snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen after surgery and stored at −70°C until analysis. The histopathological diagnosis and classification were based on the tumor location, the tumor growth pattern, on signs of secretory granules as determined by immunohistochemical analysis of Chromogranin A, and/or a positive reaction with the Grimelius silver technique, and finally on a positive reaction for Masson’s silver staining as a marker of serotonin production. 3 In addition, the size of the primary tumor, and the presence of metastases to the lymph nodes and the liver were recorded for each patient (Table 1) ▶ .

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the 18 Midgut Carcinoids in the Study

| Case no. | Lab i.d. | Age | Sex | Histopathological diagnosis | Staining for Grimelius and/or Chromogranin A | Staining for Masson | Size* (cm) | Metastases | Analyzed | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lgl | Liver | |||||||||

| 1 | 2192 | 63 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.5 | Yes | Primary | |

| 2 | 2289 | 64 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.5 | Yes | Yes | Primary |

| 3 | 576 | 69 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 4–5 | Yes | Metastasis | |

| 4 | 1302 | 71 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 0.8 | Yes | Primary | |

| 5 | 1845 | 77 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | 1 | Yes | Primary | ||

| 6 | 1454 | 46 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 3.5 | Yes | Yes | Primary |

| 7 | 1130 | 69 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1 | Yes | Primary | |

| 8 | 1916 | 71 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | 2.5 | Yes | Primary | ||

| 9 | 1320 | 75 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.2 | Primary | ||

| 10 | 1386 | 39 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.3 | Yes | Yes | Primary |

| 11 | 738 | 44 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.8 | Yes | Yes | Primary |

| 12 | 1400 | 50 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.5 | Yes | Yes | Primary |

| 13 | 690 | 73 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 2.5 | Yes | Yes | Metastasis |

| 14 | 350 | 57 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 3–4 | Yes | Primary | |

| 15 | 1281 | 65 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 5 | Yes | Yes | Metastasis |

| 16 | 119 | 74 | M | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 2 | Yes | Yes | Primary |

| 17 | 38 | 53 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.2 | Yes | Metastasis | |

| 18 | 88 | 59 | F | Midgut carcinoid | Positive | Positive | 1.7 | Yes | Yes | Metastasis |

*The size given refers to that of the primary tumor.

Nine of the 18 tumor specimens were from female patients and nine were from males, and the median age at the initial surgery of all patients was 62 years (range, 39 to 77 years). By histopathological investigation all frozen tumor samples included in this study were shown to contain a minimum of 80% tumor cells. Informed consent was obtained from all patients, and the study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Karolinska Hospital.

CGH

High molecular weight DNA was isolated from frozen tumor tissues according to standard procedures and used for CGH analyses. CGH was performed essentially as previously described. 17 Briefly, tumor DNA samples were labeled with fluorescein isothiocyanate-dUTP (DuPont, Boston, MA) by nick translation, and normal reference DNA was labeled with Texas Red-dUTP (Vysis Inc., Downers Grove, IL). Tumor and reference DNA were then mixed with unlabeled Cot-1 DNA (Life Technologies, Inc., Gaithersburg, MD), denatured, and applied onto slides with denatured metaphases of normal lymphocytes (Vysis Inc.). After hybridization at 37°C for 48 hours, the slides were washed in 0.4× standard saline citrate/0.3% Nonidet P-40 at 74°C for 2 minutes and in 2× standard saline citrate/0.1% Nonidet P-40 at room temperature for 1 minute. After air drying, the slides were counterstained with 4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (Vysis Inc.). Two control experiments were performed. In the first, normal male and normal female DNAs were labeled and hybridized to normal metaphases. For the second experiment, DNA from a previously characterized breast cancer cell line (MPE 600, Vysis Inc.) and DNA from a normal female were labeled and hybridized to normal male metaphases.

Ten three-color digital images (4,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole, fluorescein isothiocyanate, and Texas Red fluorescence) were collected from the hybridizations using a Zeiss Axioplan 2 (Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) epifluorescence microscope and Sensys (Photometrics, Tucson, AZ) charge-coupled device camera interfaced to a IPLab Spectrum 10 workstation (Signal Analytics Corporation, Vienna, VA). Green-to-red (g/r) fluorescence ratios <0.8 were considered as losses whereas ratios >1.2 were scored as gains of genetic material. Heterochromatic regions, the short arm of the acrocentric chromosomes, and chromosome Y were not included in the evaluation.

LOH Studies

Matched pairs of blood and tumor DNA samples from nine patients (cases 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, 11, 15, and 18) were genotyped for six polymorphic microsatellite markers including D18S1270, D18S541, D18S858, D16S2624, D16S539, and D16S422. The markers were labeled with fluorescent dyes (ie, HEX, TET, FAM). Fifty ng of DNA was amplified in a 10-μl reaction solution containing 1.0 μl 10× buffer (Finnzyme, Oy), 1 mmol/L MgCl2 (Perkin Elmer, Emeryville, CA), 0.5 μmol/L primer pairs, 0.1 mmol/L dNTPs, and 0.2 μl DNA polymerase (Dynazyme, Finnzyme, Oy). Amplifications were performed using a 10-minute initial denaturation at 95°C, followed by 30 cycles of 30 seconds at 94°C, 30 seconds at 55°C or 60°C, and 30 seconds at 72°C, and a final 5-minute extension at 72°C. The fluorescently labeled PCR products were electrophoresed using 5% polyacrylamide gels (Long Ranger; FMC BioProducts, ME) on an ABI 377 apparatus (Applied Biosystems, Perkin Elmer) and the results were analyzed by Genescan Analysis 3.1 software package (Applied Biosystems, Perkin Elmer). LOH was confirmed when the ratio of allele intensity of the tumor DNA to normal DNA was 50% or less.

Statistical Analyses

Individual chromosome copy number changes of midgut carcinoids and bronchial carcinoids 10 were compared using the Fisher’s exact test, and correlations between CGH aberrations and clinical and histopathological features were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test in the StatView 4.5 software. Probabilities of <0.05 were accepted as significant.

Results

In this study 18 midgut carcinoids were screened for numerical imbalances using CGH. The diagnosis was verified in each case by histopathological evaluation and positive Masson staining indicating serotonin production. In addition 16 of the tumors were positive for immunohistochemical analyses of Chromogranin A and/or histochemical Grimelius silver staining (Table 1) ▶ . Furthermore, 16 of the patients demonstrated one or more of the symptoms that are typical for a carcinoid syndrome, ie, flush, episodic diarrhea/abdominal pain, cardiac failure, and asthma-like symptoms.

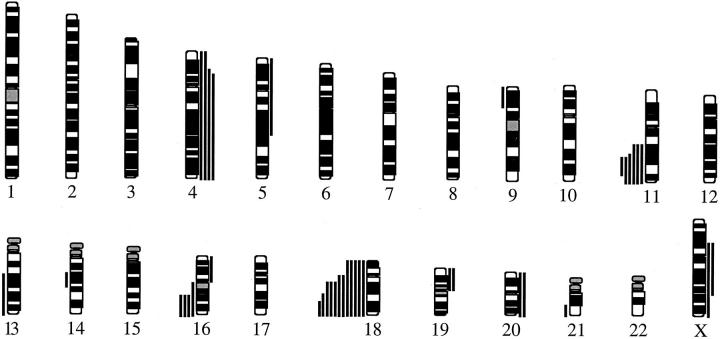

DNA samples from all 18 tumor samples were successfully analyzed by CGH. The chromosomal regions with increased and decreased DNA sequence copy numbers are illustrated in Figure 1 ▶ and detailed for each tumor in Table 2 ▶ . The mean number of CGH alterations per tumor was 2.1 ± 1.7, mean ± SD (range, 0 to 6). Numerical imbalances were detected in 16 of the 18 tumors, and losses were more common than gains. The most commonly seen losses were detected at 18q22-qter (67%), 11q22-q23 (33%), and 16q21-qter (22%), whereas gains most frequently involved 4p14-qter (22%). High-level amplifications were not detected.

Figure 1.

Summary of DNA copy number alterations detected by CGH in 18 midgut carcinoids. Each line represents one alteration detected in one tumor, with losses illustrated to the left and gains to the right of the ideograms.

Table 2.

The Most Frequent CGH Alterations in Relation to the Total Number of Alterations in the 18 Midgut Carcinoids

| Case no. | No. of changes | Losses and gains involving chromosomal regions | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loss 18q22-qter | Loss 11q22-q23 | Loss 16q21-qter | Gain 4p14-qter | Other losses | Other gains | ||

| 1 | 0 | ||||||

| 2 | 0 | ||||||

| 3 | 1 | 18 | |||||

| 4 | 1 | 18q | |||||

| 5 | 1 | 18q22-qter | |||||

| 6 | 1 | 18q21-qter | |||||

| 7 | 1 | Xp11-qter | |||||

| 8 | 1 | Xp11-q24 | |||||

| 9 | 1 | 11q22-q23 | |||||

| 10 | 2 | 18 | 19p | ||||

| 11 | 2 | 18q12-qter | 11q14-qter | ||||

| 12 | 2 | 18q | 11q14-qter | ||||

| 13 | 2 | 18q12-qter | 16q21-qter | ||||

| 14 | 3 | 18q12-qter | 4p15.1-qter | 21q22 | 5pter-q22 | ||

| 15 | 4 | 18 | 11q22-qter | 16q21-qter | 4p14-qter | ||

| 16 | 4 | 18 | 9p21-pter, 13q21-qter | 16p | |||

| 17 | 5 | 11q14-qter | 16q | 4 | 14q21-q22 | 20 | |

| 18 | 6 | 18 | 11q21-qter | 16q21-qter | 4 | 19p, 20 | |

The CGH findings for chromosomes 16q and 18q were confirmed through LOH analyses of nine blood-tumor pairs by typing of three microsatellites on distal 18q and three microsatellites on distal 16q. In all nine cases the findings by LOH were completely in agreement with the CGH results. Cases 3, 4, 11, 15, and 18 showed LOH for all informative markers on 18q and also loss by CGH, whereas in cases 2, 6, 8, and 9 no losses were seen either by LOH or by CGH. Furthermore cases 15 and 18 demonstrated LOH with all informative 16q markers and also loss of the same region by CGH, whereas cases 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 9, and 11 had retained heterozygosity and no CGH losses for 16q.

The four most frequently detected CGH alterations were compared to the total number of alterations in the individual tumors, and whether they were detected in primary tumor specimens or in metastases. These comparisons revealed several significant correlations. The pattern of CGH alterations in the individual tumors were found to vary depending on the total number of detected alterations (Table 2) ▶ . Loss of 18q22-qter and loss of 11q22-q23 were both detected as single aberrations in four and one cases, respectively. However, loss of 16q21-qter and gain of 4p14-qter were only detected in tumors having a total of two to six alterations (Table 2) ▶ . Furthermore, the total number of alterations found in the metastases were significantly higher than in the primary tumors (P = 0.036, Mann-Whitney). Losses of 18q22-qter and 11q22-q23 were detected both in primary tumors and metastases without significantly different frequencies (Table 3) ▶ . However, significantly different frequencies were seen for loss of 16q21-qter that were only seen in metastases (P = 0.0016, Fisher’s exact test), and gain of 4p14-qter that was present mainly in metastases (P = 0.044, Fisher’s exact test) (Table 3) ▶ . Taken together, the findings would suggest a progression of numerical imbalances, in which loss of 18q22-qter and 11q22-q23 represent early events in the tumorigenesis, and loss of 16q21-qter and gain of 4p14-qter are late events associated with metastasizing of midgut carcinoids.

Table 3.

The Most Frequent CGH Alterations Detected in Primary Tumors as Compared to Metastases of Midgut Carcinoids in This Study

| Alteration | Primary tumors | Metastases | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|

| Loss 18q22-qter | 8 /13 | 4 /5 | n.s. |

| Loss 11q22-q23 | 3 /13 | 3 /5 | n.s. |

| Loss 16q21-qter | 0 /13 | 4 /5 | 0.0016 |

| Gain 4p14-qter | 1 /13 | 3 /5 | 0.0441 |

*n.s., not significant.

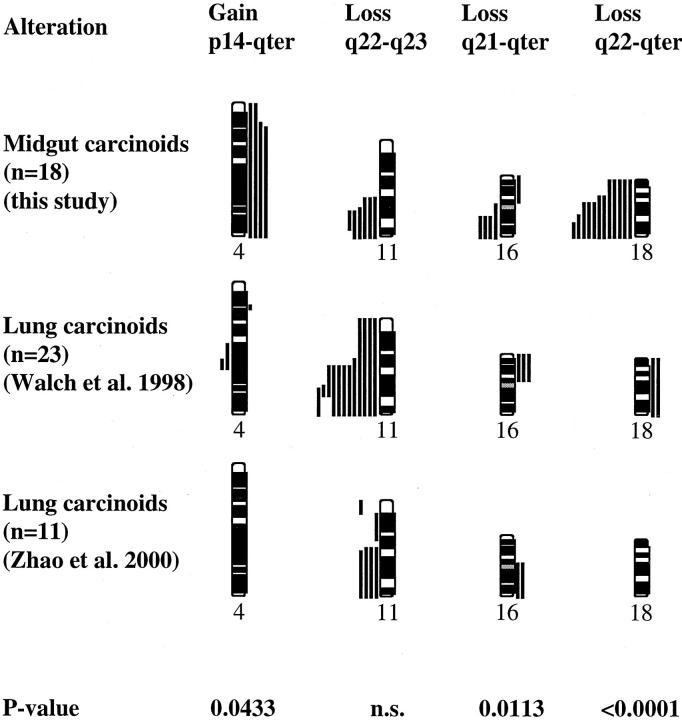

The four most frequently detected CGH alterations were also compared to previously published findings in the same regions in foregut carcinoids from the lung (Figure 2) ▶ . 10,12 Both tumor types demonstrated frequent loss of 11q22-q23, in frequencies that did not vary significantly between the two types of tumors. However, loss of 18q22-qter, which was seen in the majority of midgut carcinoids (12 of 18), were not reported in any of the lung carcinoids (P < 0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). Similarly, loss of 16q21-qter as well as gain of 4p14-pter, detected solely in metastases from midgut carcinoids, was not detected in lung carcinoids (P = 0.011 and P = 0.043, respectively, Fisher’s exact test) (Figure 2) ▶ .

Figure 2.

Comparison between the most frequent copy number imbalances detected by CGH in midgut carcinoids in the present study and in lung carcinoids as previously published. 10,12 Each line represents one alteration detected in one tumor, with losses illustrated to the left and gains to the right of the ideograms.

Discussion

Acquired genetic changes are the main causes of malignant transformation of somatic cells. In a variety of malignant tumors, identification and classification of these aberrations have proved to be of great value for diagnostic, prognostic, and treatment purposes. In the present study four recurrent numerical chromosomal abnormalities were identified by CGH in 16 of the 18 cases analyzed. In two cases no CGH alterations were detected, which could be because of balanced aberrations not affecting DNA sequence copy number or aberrations beyond the resolution capacity of CGH.

The four recurrent numerical imbalances detected included losses of 18q22-qter, 11q22-q23, and 16q21-qter, and gains of 4p14-qter. Chromosome 18q, especially the region of 18q12.3-q21.3, is frequently deleted in many types of tumors, 18 such as pancreatic and colorectal tumors. 19,20 Three tumor suppressor genes located in the 18q12.3-q21.3 region, MADH2/SMAD2 at 18q12.3, MADH4/SMAD4 in 18q21.1, and DCC in 18q21.2, have been evaluated as targets for the frequent deletions, but specific alterations of these genes have only been rarely described. 21-23 The minimal region of overlapping deletions detected in midgut carcinoids was mapped to 18q22-qter, which is located immediately distal to the region mentioned above. This would suggest the existence of a yet uncharacterized tumor suppressor gene locus whose inactivation represents a frequent and early event in the development of midgut carcinoids. Interestingly, no 18q losses were detected in two independent CGH studies of lung carcinoids, 10,12 whereas this was the most common alteration in midgut carcinoids, indicating that the gene in 18q is specifically involved in the early development of midgut carcinoids but not in carcinoids of the lung.

Loss of 11q22-q23 occurs frequently in both hematological malignancies and in many types of solid tumors, such as breast, lung, cervical, and ovarian carcinoma and melanoma. 18 The long arm of chromosome 11 is gene-rich and harbors multiple tumor suppressor genes especially within the region of q22-q23, which thus represent candidate genes for carcinogenesis of midgut carcinoids. The PPP2R1B gene (the serine/threonine protein phosphatase subunit locus), has been shown to be mutated in lung and colon cancer, 24 and recently, the SDHD (succinate-ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunit D) gene in 11q23 was demonstrated to be responsible for hereditary paraganglioma. 25 The role of the ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) gene in carcinogenesis is still not clear, but it is assumed to function as a tumor suppressor gene, and has been thoroughly studied in breast cancer. 26 Other possible candidate genes include CHK1, a protein kinase required for the DNA damage checkpoint, 27 LOH11CR2A, 28 and DDX10, a putative RNA helicase, 29 and ALL-1 (disrupted in acute leukemias) 30 that all reside within 11q23.

Homozygous inactivation of the MEN1 tumor suppressor gene in 11q13 by mutation of one allele and loss of the second allele through a gross deletion, has been observed in a third of sporadic lung carcinoids. 8 Interestingly, loss of 11q in lung carcinoids was never restricted to the MEN1 gene locus in 11q13, but always extended distally to the 11q22 region (Figure 2) ▶ . On the other hand, loss of 11q22-q23 has been seen in lung carcinoids without loss of 11q13. 7,10 This could be interpreted as indicating that both MEN1 and a more distally located gene on 11q are involved in lung carcinoids. Furthermore, because the minimal regions of loss are the same in midgut and lung carcinoids (Figure 2) ▶ , it is likely that one and the same gene in 11q22-q23 is involved in both types of tumors.

Carcinogenesis can be regarded as a multistep process, which is associated with the accumulation of genetic alterations, 31-33 and this view may also be applied to the development of midgut carcinoids. Consequently, more CGH alterations were seen in the metastatic lesions than in the primary tumors analyzed, and in addition the pattern of CGH alterations varied depending on the total number of detected alterations. Taken together, the findings were suggestive of a progression of numerical imbalances, in which loss of 18q and 11q represent early events, and loss of 16q and gain of 4p are late events associated with the tumor progression. Identification of the exact molecular alterations reflected by these numerical imbalances is likely to bring along an improved understanding of carcinogenesis of midgut carcinoids. Furthermore, these will provide starting points for the development of markers for diagnostic purposes.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lisa Ånfalk and Ann Svensson for their excellent technical assistance in processing the tumor specimens.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Catharina Larsson, M.D., Ph.D., Endocrine Tumour Unit, Center for Molecular Medicine, Karolinska Hospital CMM L8:01, SE-171 76 Stockholm Sweden. E-mail: catharina.larsson@cmm.ki.se.

Supported by the Swedish Cancer Foundation, The Torsten and Ragnar Söderberg Foundations, and the Cancer Society in Stockholm.

References

- 1.Modlin IM, Sandor A: An analysis of 8305 cases of carcinoid tumors. Cancer 1997, 79:813-829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berge T, Linell F: Carcinoid tumours: frequency in a defined population during a 12-year period. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand 1976, 84:322-330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lechago J, Shah IA: The endocrine digestive system. ed 2 Kovacs K Asa SL eds. Functional Endocrine Pathology, 1998, :pp 488-512 Blackwell Science, Oxford [Google Scholar]

- 4.Duh Q-Y, Hybarger CP, Geist R, Gamsu G, Goodman PC, Gooding GAW, Clark OH: Carcinoids associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes. Am J Surg 1987, 154:142-148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chandrasekharappa SC, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi S-E, Collins FS, Emmert-Buck MR, Debelenko LV, Zhuang Z, Lubenksy IA, Liotta LA, Crabtree JS, Wang Y, Roe BA, Weisemann J, Boguski MS, Agarwal SK, Kester MB, Kim YS, Heppner C, Dong Q, Spiegel AM, Burns AL, Marx SJ: Positional cloning of the gene for multiple endocrine neoplasia-type 1. Science 1997, 276:404-407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.: The European Consortium on MEN: Identification of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN1) gene. Hum Mol Genet 1997, 6:1177-1183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jakobovitz O, Nass D, DeMarco L, Barbosa AJ, Simoni FB, Rechavi G, Friedman E: Carcinoid tumors frequently display genetic abnormalities involving chromosome 11. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996, 81:3164-3167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Debelenko LV, Brambilla E, Agarwal SK, Swalwell JI, Kester MB, Lubensky IA, Zhuang Z, Guru SC, Manickam P, Olufemi S-E, Chandrasekharappa S, Crabtree JS, Kim YS, Heppner C, Burns AL, Spiegel AM, Marx SJ, Liotta LA, Collins FS, Travis WD, Emmert-Buck MR: Identification of MEN1 gene mutations in sporadic carcinoid tumors of the lung. Hum Mol Genet 1997, 6:2285-2290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emmert-Buck MR, Lubensky IA, Dong Q, Manickam P, Guru SC, Kester MB, Olufemi SE, Agarwal S, Burns AL, Spiegel AM, Collins FS, Marx SJ, Zhuang Z, Liotta LA, Chandrasekharappa SC, Debelenko LV: Localization of the multiple endocrine neoplasia type I (MEN1) gene based on tumor loss of heterozygosity analysis. Cancer Res 1997, 57:1855-1858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Walch AK, Zitzelsberger HF, Aubele MM, Mattis AE, Bauchinger M, Candidus S, Präuer HW, Werner M, Höfler H: Typical and atypical carcinoid tumors of the lung are characterized by 11q deletions as detected by comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Pathol 1998, 153:1089-1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Onuki N, Wistuba II, Travis WD, Virmani AK, Yashima K, Brambilla E, Hasleton P, Gazdar AF: Genetic changes in the spectrum of neuroendocrine lung tumors. Cancer 1999, 85:600-607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao J, de Krijger RR, Meier D, Speel EJ, Saremaslani P, Muletta-Feurer S, Matter C, Roth J, Heitz PU, Komminoth P: Genomic alterations in well-differentiated gastrointestinal and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors (carcinoids): marked differences indicating diversity in molecular pathogenesis. Am J Pathol 2000, 157:1431-1438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Terris B, Meddeb M, Marchio A, Danglot G, Fléjou J-F, Belghiti J, Ruszniewski P, Bernheim A: Comparative genomic hybridization analysis of sporadic neuroendocrine tumors of the digestive system. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1998, 22:50-56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Caron de Fromentel C, Soussi T: TP53 tumor suppressor gene: a model for investigating human mutagenesis. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1992, 4:1-15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lohmann DR, Fesseler B, Putz B, Reich U, Bohm J, Prauer H, Wunsch PH, Hofler H: In frequent mutations of the p53 gene in pulmonary carcinoid tumors. Cancer Res 1993, 53:5797-5801 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lohmann DR, Funk A, Niedermeyer HP, Häupel S, Höfler H: Identification of p53 gene mutations in gastrointestinal and pancreatic carcinoids by nonradioisotoic SSCA. Virchows Arch B Cell Pathol 1993, 64:293-296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kallioniemi O-P, Kallioniemi A, Piper J, Isola J, Waldman FM, Gray JW, Pinkel D: Optimizing comparative genomic hybridization for analysis of DNA sequence copy number changes in solid tumors. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1994, 10:231-243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knuutila S, Aalto Y, Autio K, Björkqvist A-M, El-Rifai W, Hemmer S, Huhta T, Kettunen E, Kiuru-Kuhlefelt S, Larramendy ML, Lushnikova T, Monni O, Pere H, Tapper J, Tarkkanen M, Varis A, Wasenius V-M, Wolf M, Zhu Y: DNA copy number losses in human neoplasms. Rev Am J Pathol 1999, 155:683-694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cho KR, Oliner JD, Simons JW, Hedrick L, Fearon ER, Preisinger AC, Hedge P, Silvermann GA, Vogelstein B: The DCC gene: structural analysis and mutations in colorectal carcinomas. Genomics 1994, 19:525-531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hahn SA, Seymour AB, Hoque ATMS, Schutte M, da Costa LT, Reston MS, Caldas C, Weinstein CL, Fischer A, Yeo CJ, Hruban RH, Kern SE: Allelotype of pancreatic adenocarcinoma using a xenograft model. Cancer Res 1995, 55:4670-4675 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cho KR, Fearon ER: DCC: linking tumor suppressor genes and altered cell surface interactions in cancer? Curr Opin Genet Dev 1995, 5:72-78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Eppert K, Scherer SW, Ozcelik H, Pirone R, Hoodless P, Kim H, Tsui LC, Bapat B, Gallinger S, Andrulis IL, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL, Attisano L: MADR2 maps to 18q21 and encodes a TGFbeta-regulated MAD-related protein that is functionally mutated in colorectal carcinoma. Cell 1996, 86:543-552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takagi Y, Koumura H, Futamura M, Aoki S, Yamaguchi K, Kida H, Tanemura H, Shimokawa K, Saji S: Somatic alterations of the Smad-2 gene in human colorectal cancers. Br J Cancer 1998, 78:1152-1155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang SS, Esplin ED, Li JL, Huang L, Gazdar A, Minna J, Evans GA: Alterations of the PPP2R1B gene in human lung and colon cancer. Science 1998, 282:284-287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baysal BE, Ferrell RE, Willett-Brozick JE, Lawrence EC, Myssiorek D, Bosch A, van der Mey A, Taschner PEM, Rubinstein WS, Myers EN, Richard CW, III, Cornelisse CJ, Devilee P, Devlin B: Mutations in SDHD, a mitochondrial complex II gene, in hereditary paraganglioma. Science 2000, 287:848-851 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khanna KK: Cancer risk and the ATM gene: a continuing debate. J Natl Cancer Inst 2000, 92:795-802 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sanchez Y, Wong C, Thoma RS, Richman R, Wu Z, Piwnica-Worms H, Elledge SJ: Conservation of the Chk1 checkpoint pathway in mammals: linkage of DNA damage to Cdk regulation through Cdc25. Science 1997, 277:1497-1501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monaco C, Negrini M, Sozzi G, Veronese ML, Vorechovsky I, Godwin AK, Croce CM: Molecular cloning and characterization of LOH11CR2A, a new gene within a refined minimal region of LOH at 11q23. Genomics 1997, 46:217-222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Savitsky K, Ziv Y, Bar-Shira A, Gilad S, Tagle DA, Smith S, Uziel T, Sfez S, Nahmias J, Sartiel A, Eddy RL, Shows TB, Collins FS, Shiloh Y, Rotman G: A human gene (DDX10) encoding a putative DEAD-box RNA helicase at 11q22–q23. Genomics 1996, 33:199-206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baffa R, Negrini N, Schicman SA, Huebner K, Croce CM: Involvement of the ALL-1 gene in a solid tumor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995, 92:4922-4926 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Heselmeyer K, Schröck E, du Manoir S, Blegen H, Shah K, Steinbeck R, Auer G, Ried T: Gain of chromosome 3q defines the transition from severe dysplasia to invasive carcinoma of the uterine cervix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1996, 93:479-484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kjellman M, Kallioniemi O-P, Karhu R, Höög A, Farnebo L-O, Larsson C, Bäckdahl M: Genetic changes in adrenocortical tumors detected by comparative genomic hybridization correlate with tumor size and malignancy. Cancer Res 1996, 56:4219-4223 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ried T, Knutzen R, Steinbeck R, Blegen H, Schröck E, Heselmeyer K, du Manoir S, Auer G: Comparative genomic hybridization reveals a specific patter of chromosomal gains and losses during the genesis of colorectal tumors. Genes Chromosom Cancer 1996, 15:234-245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]