Abstract

Background

Little population-based data exist on the prevalence or correlates of eating disorders.

Methods

Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders from the National Comorbidity Replication, a nationally representative face-to-face household survey (n _ 9282), conducted in 2001–2003, were assessed using the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview.

Results

Lifetime prevalence estimates of DSM-IV anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder are .9%, 1.5%, and 3.5% among women, and .3% .5%, and 2.0% among men. Survival analysis based on retrospective age-of-onset reports suggests that risk of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder increased with successive birth cohorts. All 3 disorders are significantly comorbid with many other DSM-IV disorders. Lifetime anorexia nervosa is significantly associated with low current weight (body-mass index18.5), whereas lifetime binge eating disorder is associated with current severe obesity (body-mass index < _ 40). Although most respondents with 12-month bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder report some role impairment (data unavailable for anorexia nervosa since no respondents met criteria for 12-month prevalence), only a minority of cases ever sought treatment.

Conclusions

Eating disorders, although relatively uncommon, represent a public health concern because they are frequently associated with other psychopathology and role impairment, and are frequently under-treated.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa, eating disorders, epidemiology, national comorbidity survey replication (NCS-R)

Two eating disorders—anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa—are recognized as diagnostic entities in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) (American Psychiatric Association 1994); a third category, binge eating disorder, is proposed in DSM-IV as a possible new diagnostic entity. However, data are incomplete on the prevalence of these 3 disorders in the general population. The prevalence of anorexia nervosa has been investigated mainly in samples of young women in Europe and North America, where the average point prevalence has been .3% (Hoek and van Hoeken 2003; Favaro et al 2004). The lifetime prevalence among adult women has been reported as .5%–.6% in 2 large population-based surveys in the United States (Walters and Kendler 1995) and Canada (Garfinkel et al 1996); the latter study found a prevalence of anorexia nervosa among adult men of .1%. The lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa in adult women has been estimated as 1.1%–2.8% in 3 large populationbased surveys in New Zealand (Bushnell et al 1990), the United States (Kendler et al 1991), and Canada (Garfinkel et al 1995). For men, the lifetime prevalence of bulimia nervosa was estimated at .1% in the Canadian study and .2% in the New Zealand study, but the point prevalence of bulimia nervosa in a study in Austria was reported as .5% (Kinzl et al 1999b). For the case of binge eating disorder, 2 population-based telephone interview surveys of adults in Austria estimated the point prevalence as 3.3% among women (Kinzl et al 1999a) and .8% among men (Kinzl et al 1999b). Other studies of binge eating disorder have been limited to specific populations (e.g., young women) or were based only on questionnaires, rather than personal interviews (Streigel-Moore and Franko 2003; Favaro et al 2004).

Population-based interview data are needed to ascertain the prevalence of the 3 eating disorders as well as to provide data on age-of-onset distributions, duration, and association with sociodemographics and body-mass index (BMI). Population data could also address the question of cohort effects—whether the incidence of eating disorders has changed in recent decades. Also of interest is the association of eating disorders with other mental disorders, with measures of disability, and with history of mental health treatment. Finally, population-based data may be useful in examining alternative definitions of eating disorder syndromes in order to determine which definitions are most meaningful as markers of psychopathology. To address these questions, we analyzed data from the recently completed National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R).

Methods and Materials

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative survey of the US household population that was administered face-to-face to a sample of 9282 English-speaking adults ages 18 and older between February 2001 and December 2003 (Kessler and Merikangas 2004). The response rate was 70.9%. The sample was based on a multi-stage clustered area probability design. Recruitment featured an advance letter and Study Fact Brochure followed by in-person interviewer visits to obtain informed consent. Consent was verbal rather than written in order to parallel the consent procedures in the baseline NCS (Kessler et al 1994). Respondents were given a $50 financial incentive for participation. The Human Subjects Committees of both Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan approved these recruitment and consent procedures.

The survey was administered in 2 parts. Part I included the core diagnostic assessment and was administered to all respondents. Part II assessed additional disorders and correlates of disorders. Part II was administered to a subset of 5692 respondents consisting of all those who met lifetime criteria for a Part I disorder plus a probability sample of other respondents. Disorders of secondary interest were administered to probability sub-samples of the Part II sample. Eating disorders were among the latter disorders.

The analyses reported here were carried out in a sub-sample of 2980 Part II respondents who were randomly assigned to have an assessment of eating disorders. Data records in this subsample were weighted to adjust for the over-sampling of Part I respondents with a mental disorder, differential probabilities of selection within households, systematic non-response, and residual socio-demographic-geographic differences between the sample and the 2000 Census. NCS-R sampling and weighting are discussed in more detail elsewhere (Kessler et al 2004b).

Diagnostic Assessment

NCS-R diagnoses were based on Version 3.0 of the World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) (Kessler and Ustun 2004), a fully structured layadministered diagnostic interview that generates diagnoses according to both ICD-10 and DSM-IV criteria. DSM-IV criteria were used in the current report. Core disorders included the three broad classes of disorder assessed in previous CIDI surveys (anxiety disorders, mood disorders, and substance disorders) plus a group of disorders that share a common feature of difficulties with impulse control (e.g., intermittent explosive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, retrospectively reported childhood oppositional-defiant disorder, and conduct disorder). Diagnostic hierarchy rules and organic exclusion rules were used in making all diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere (Kessler et al 2004a, 2005), good concordance was found between these core CIDI diagnoses and diagnoses based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (First et al 2002) in a probability sub-sample of NCS-R respondents who were administered clinical reappraisal interviews. The area under the receiver operator characteristic curve was in the range of .65–.81 for anxiety disorders, .75 for major depressive episode, .62–.88 for substance disorders, and .76 for any anxiety, mood, or substance disorder. No clinical reappraisal interviews were carried out for the impulse-control disorders, as these were not core NCS-R disorders.

For the present study, questions from the CIDI were used to assign diagnoses of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder based on DSM-IV criteria. The full diagnostic algorithms for all 3 disorders, together with a sensitivity analysis using alternative, narrower definitions of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, are presented as supplemental material available online with the electronic version of this article and at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs//eating.php; the corresponding CIDI questions used to operationalize the criteria are available at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs.

Most of the CIDI questions closely paralleled the DSM-IV criteria, but to meet criteria for binge eating disorder, DSM-IV requires a minimum of 6 months of regular eating binges, whereas the CIDI asked only whether the individual experienced 3 months of symptoms. Thus, individuals displaying more than 3 months, but less than 6 months, of regular binge eating would be classified as having binge eating disorder in our algorithm, but not in DSM-IV. Also of note is that for binge eating episodes in bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, DSM-IV requires assessment of loss of control, and for binge eating disorder requires marked distress regarding binge eating; these items were assessed in the CIDI by a series of questions about attitudes and behaviors that are indicators of loss of control and of distress, rather than by direct questions.

In addition to the 3 eating disorders, we also defined 2 provisional entities. The first was “subthreshold binge eating disorder,” defined as a) binge eating episodes, b) occurring at least twice a week for at least 3 months, and c) not occurring solely during the course of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder. Thus, subthreshold binge eating disorder did not require DSM-IV criterion B (3 of 5 features associated with binge eating) or C (marked distress regarding binge eating for binge eating disorder). The second was “any binge eating,” also defined as a) binge eating episodes (again, not requiring DSM-IV criteria B and C), b) occurring at least twice a week for at least 3 months, but c) lacking the hierarchical exclusion criterion if the individual simultaneously exhibited another eating disorder. In other words, any binge eating was diagnosed regardless of whether or not the individual simultaneously met criteria for any of the other 3 eating disorders or for subthreshold binge eating disorder. This entity thus included all cases of bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and subthreshold binge eating disorder, as well as cases of anorexia nervosa with binge eating. Full diagnostic algorithms for these 2 provisional entities, together with a sensitivity analysis parallel to that above, are presented as supplemental material available with the online version of this article and at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs//eating.php.

In summary, we examined a total of 5 conditions—2 official DSM-IV disorders (anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa), 1 proposed DSM-IV disorder (binge eating disorder), and 2 provisional entities that partially overlapped with 1 or more of the previous 3 disorders. Although in the following text we refer to these 5 conditions collectively as “disorders” for simplicity, the reader should bear in mind that they vary in terms of their level of general acceptance.

As indicated above, our criteria allowed that individuals could display more than one lifetime diagnosis of an eating disorder. We used data from the CIDI regarding time of onset and recency (i.e., the time when the disorder was last present) to apply diagnostic hierarchies, so that bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and subthreshold binge eating disorder were not diagnosed in the presence of anorexia nervosa; and so that binge eating disorder and subthreshold binge eating disorder were not diagnosed in the presence of bulimia nervosa. Because the CIDI provides information only about onset and recency of a disorder, individuals with an episode of a given eating disorder occurring only in between two or more discrete episodes of a hierarchically exclusionary disorder (e.g., anorexia nervosa) would not have been diagnosed with that disorder.

For individuals meeting criteria for any of the 5 five disorders, the CIDI assessed age of onset, recency, years with the disorder, and professional help-seeking. Respondents with 12-month prevalence (that is, individuals who met criteria for the eating disorder at any time within the 12 months before interview) were additionally administered the Sheehan Disability Scales (Leon et al 1997) to assess the severity of recent episodes and were asked about treatment in the past 12 months.

Statistical Analyses

Cross-tabulations were used to estimate prevalence, disability, and treatment. The actuarial method (Wolter 1985) was used to estimate age-of-onset curves. Discrete-time survival analysis with the person-year as the unit of analysis (Willett and Singer 1993) using logistic regression (Hosmer and Lemeshow 2000) was used to estimate cohort effects. Logistic regression was also used to study socio-demographic correlates and comorbidity. Logits and their 95% confidence intervals were converted into odd ratios by exponentiation for ease of interpretation. Standard errors and significance tests were estimated using the Taylor series linearization method (Wolter 1985) implemented in the SUDAAN software system (Research Triangle Institute 2002) to adjust for the weighting and clustering of the NCS-R data. Multivariate significance of predictor sets was evaluated using Wald _ 2 tests based on design-corrected coefficient variance-covariance matrices. Statistical significance was evaluated using 2-tailed .05-level tests; it should be noted that this level, which was pre-specified for all NCS-R analyses, does not correct for multiple comparisons and thus underestimates the overall type I error rate.

Results Prevalence

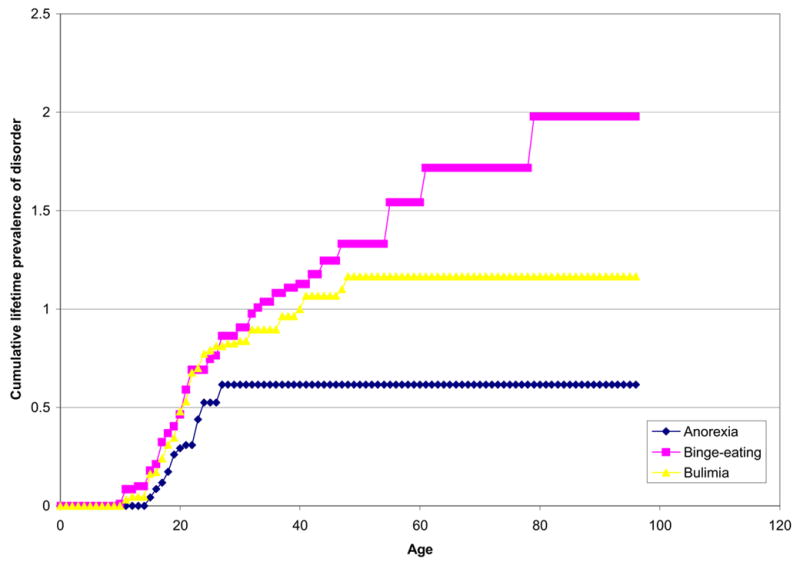

Lifetime prevalence estimates of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, subthreshold binge eating disorder, and any binge eating were .6%, 1.0%, 2.8%, 1.2%, and 4.5% (Table 1). Lifetime prevalence was consistently 1¾ to 3 times as high among women as men for the 3 eating disorders (z _ 2.2–2.8, P _ .029–.005), 3 times as high among men as women for subthreshold binge eating disorder (z _ 3.3, P _ .001), and approximately equal among women and men for any binge eating (z _ 1.2., P _ .219). No 12-month cases of anorexia nervosa were found in the sample. The 12-month prevalence estimates of the other 4 disorders were considerably lower than the lifetime estimates, although with similar sex ratios. Estimates of cumulative lifetime risk by age 80, based on retrospective age-of-onset reports (Figure 1), were 0.6% for anorexia nervosa, 1.1% for bulimia nervosa, 3.9% for binge eating disorder, 1.4% for subthreshold binge eating disorder, and 5.7% for any binge eating.

Table 1.

Lifetime and 12-month prevalence estimates of DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior

| Male | Female | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

| I. Lifetime prevalence | ||||||

| Anorexia Nervosa | 0.3* | (0.1) | 0.9* | (0.3) | 0.6 | (0.2) |

| Bulimia Nervosa | 0.5* | (0.3) | 1.5* | (0.3) | 1.0 | (0.2) |

| Binge-eating Disorder | 2.0* | (0.5) | 3.5* | (0.5) | 2.8 | (0.4) |

| Subthreshold Binge-eating | 1.9* | (0.5) | 0.6* | (0.1) | 1.2 | (0.2) |

| Any binge-eating behavior | 4.0 | (0.7) | 4.9 | (0.6) | 4.5 | (0.4) |

| II. Twelve-month prevalence | ||||||

| Bulimia Nervosa | 0.1* | (0.1) | 0.5* | (0.2) | 0.3 | (0.1) |

| Binge-eating Disorder | 0.8* | (0.3) | 1.6* | (0.2) | 1.2 | (0.2) |

| Subthreshold binge-eating | 0.8 | (0.3) | 0.4 | (0.1) | 0.6 | (0.2) |

| Any binge-eating behavior | 1.7 | (0.4) | 2.5 | (0.3) | 2.1 | (0.2) |

| (n) | (1220) | (1760) | 2980 | |||

Significant sex difference based on a .05 level, two-sided test.

None of the respondents met criteria for 12-month Anorexia Nervosa.

Figure 1.

Age-of-onset distributions for DSM-IV eating disorders

Age of Onset and Persistence

Median age of onset of the five disorders ranged from 18–21 years (Table 2). The period of onset risk was shorter for anorexia nervosa than for the other disorders, with the earliest cases of the other disorders beginning about 5 years earlier than those of anorexia nervosa (ages 10 vs. 15), and no cases of anorexia nervosa beginning after the mid-20s—whereas some cases of the other disorders began at a much older age (Figures 1 and 2).

Table 2.

Estimated age of onset and persistence of DSM-IV eating disorders and related entities

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge Eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge Eating Disorder | Any Binge Eating | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age of onset | |||||

| Mean (se) | 18.9 (0.8) | 19.7 (1.3) | 25.4 (1.2) | 22.7 (1.9) | 22.4 (1.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 18.0 (16.0–22.0) | 18.0 (14.0–22.0) | 21.0 (17.0–32.0) | 20.0* (17.0–27.0) | 20.0* (16.0–27.0) |

| Years with episode | |||||

| Mean (se) | 1.7 (0.2) | 8.3* (1.6) | 8.1* (1.1) | 7.2* (2.0) | 8.7* (0.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–1.0) | 5.0* (2.0–13.0) | 4.0* (1.0–10.0) | 2.0* (1.0–10.0) | 3.0* (1.0–13.0) |

| 12-month persistence, % (se) | 0.0 (--) | 30.6* (7.2) | 44.2* (6.0) | 47.2* (10.0) | 46.9* (4.1) |

| (n) | (23) | (52) | (115) | (46) | (192) |

Abbreviations: se, standard error; IQR, interquartile range.

Significantly different from anorexia nervosa based on a .05 level, two-sided test.

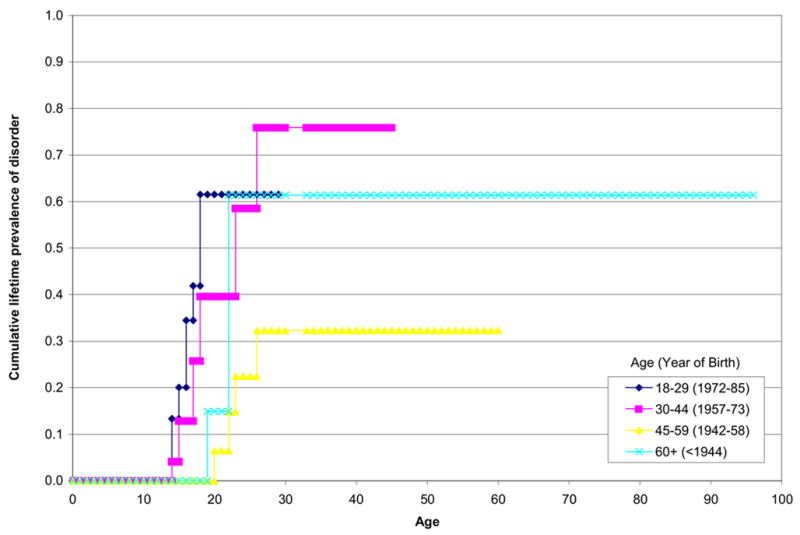

Figure 2.

Cohort-specific age-of-onset distributions for DSM-IV Anorexia Nervosa

The mean number of years with anorexia nervosa (1.7 years) was significantly lower than for either bulimia nervosa (8.3; t _ 4.1, P _ .001), binge eating disorder (8.1; t _ 2.9, P _.006), subthreshold binge eating disorder (7.2; t _ 2.6, P _ .013), or any binge eating (8.7; t _ 2.9, P _ .005) (Table 2). Consistent with these differences in duration, 12-month persistence, defined as 12-month prevalence among lifetime cases, was lowest for anorexia nervosa (.0%) and higher for bulimia nervosa (30.6%), binge eating disorder (44.2%), subthreshold binge eating (47.2%), and any binge eating (46.9%).

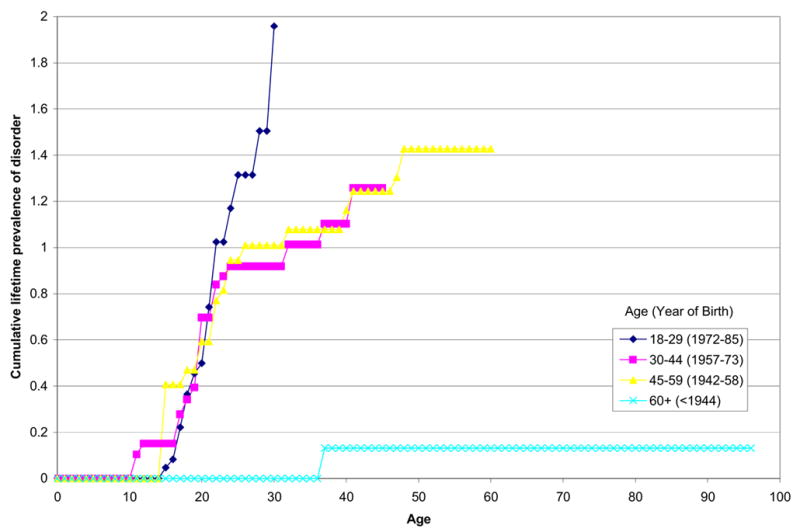

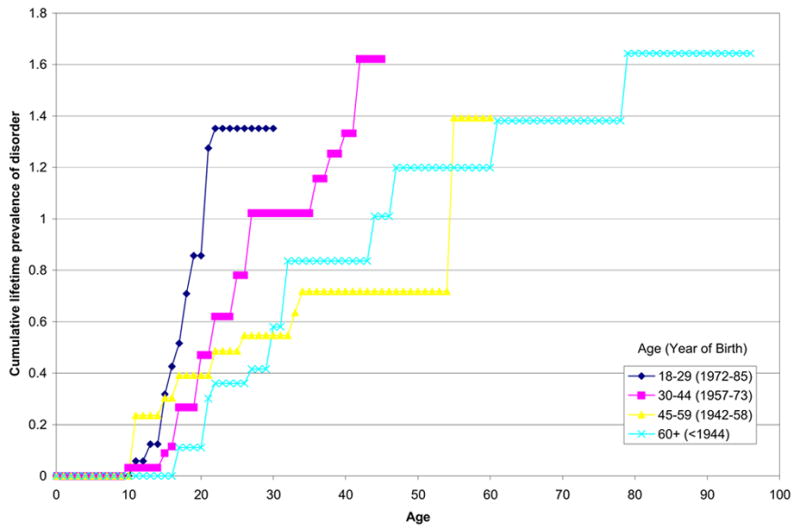

Cohort Effects

Consistent inverse associations between cohort (age at interview) and lifetime risk were found in survival analyses of all 5 disorders (Table 3). However, the odds ratios in younger (ages 18–29, 30–44) versus older (60_) cohorts were significantly higher for all comparisons only for bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and any binge eating.

Table 3.

Inter-cohort differences in lifetime risk of DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Age (year of birth) | ||||||||||

| 18–29 (1972–85) | 2.0^ | (0.7–5.3) | 16.8* | (3.0–95.6) | 4.9* | (2.1–11.5) | 4.5* | (1.8–11.2) | 4.5* | (2.6–8.0) |

| 30–44 (1957–73) | 1.8 | (0.4–8.2) | 11.8* | (1.9–72.6) | 3.1 | (1.3–7.2) | 2.2 | (0.8–6.4) | 3.0* | (1.7–5.4) |

| 45–59 (1942–58) | 0.6 | (0.1–4.5) | 13.4* | (2.2–82.2) | 2.3* | (1.1–4.9) | 1.2 | (0.3–4.3) | 2.0* | (1.1–3.8) |

| 60+ (<1944) | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | |||||

| χ23 (p-value) | 2.2 (.104) | 3.8* (.018) | 6.5* (.001) | 4.4* (.009) | 11.3* (.000) | |||||

Significant inter-cohort different based on a .05 level, two-sided test, controlling for sex and race-ethnicity.

Collapsing age categories 18–29 and 30–44 (left out category: 35 years or older) results in OR= 2.1 (.9-4.9), χ21=3.2 (p-value=0.082).

Association with Body-Mass Index

Individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of anorexia nervosa displayed a significantly lower current BMI—with a greater prevalence of a current BMI of _ 18.5, and a lower prevalence of a current BMI _ 40—than respondents without any eating disorder (Table 4). The reverse pattern was found for binge eating disorder, with a significantly higher prevalence of BMI of _ 40 among individuals with binge eating disorder than respondents without any eating disorder. Any binge eating was also associated with severe obesity, but this finding was attributable entirely to cases of binge eating disorder.

Table 4.

Difference in BMI categories at the time of interview in lifetime prevalence of DSM-IV disorders and related behavior

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Current BMI | |||||||||||||||

| < 18.5 | 15.6 | 5.6 | (0.9–33.4) | 3.5 | 1.0 | (0.2–5.3) | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.8 | 0.4 | (0.1–1.7) | ||||

| 18.5–29.9 | 79.0 | 1.0 | 65.3 | 1.0 | 57.6 | 1.0^^ | 72.1 | 1.0^^ | 63.8 | 1.0 | |||||

| 30–39.9 | 5.3 | 0.3 ^ | (0.0–2.3) | 20.9 | 1.0 | (0.4–2.7) | 27.6 | 1.7 | (0.8–3.5) | 24.4 | 1.1 | (0.5–2.8) | 24.8 | 1.3 | (0.8–2.3) |

| > 40 | 0.0 | 10.3 | 2.6 | (0.8–8.3) | 14.8 | 4.9* | (2.2–11.0) | 3.5 | 1.0 | (0.3–3.9) | 10.7 | 3.1* | (1.6–5.8) | ||

| χ23 (p-value) | 3.6*(0.035) | 1.0 (0.412) | 8.1*(0.001) | 0.0 (0.966) | 4.7* (0.007) | ||||||||||

BMI categories < 18.5 and 18.5–29.9 were collapsed

BMI categories > 40 and 30–39.9 were collapsed

Significant inter-cohort different based on a .05 level, two-sided test, controlling for age, sex and race-ethnicity.

Twelve-Month Role Impairment

Role impairment was assessed only for 12-month cases; since there were no 12-month cases of anorexia nervosa, our analysis was limited to the other 4 disorders. The majority of respondents with bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, or any binge eating reported at least some role impairment (mild, moderate, or severe) in at least 1 role domain (53.1%–78.0%), but only 21.8% of respondents with subthreshold binge eating disorder reported this degree of impairment (Table 5). Severe role impairment was much less common, and ranged from 3.4% in subthreshold binge eating to 16.3% in bulimia nervosa, with no significant differences in prevalence among groups.

Table 5.

Impairment in role functioning (Sheehan Disability Scales) associated with 12-month DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior

| Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

| I. Prevalence of any impairment | ||||||||

| Home | 43.1 | (16.4) | 46.1 | (7.1) | 18.4 | (9.7) | 38.1 | (5.8) |

| Work | 59.2 | (14.8) | 38.4 | (6.8) | 16.3 | (8.5) | 35.5 | (6.1) |

| Personal life | 47.2 | (12.3) | 39.7 | (8.8) | 15.5 | (9.1) | 34.3 | (6.0) |

| Social life | 54.1 | (14.0) | 58.8 | (7.5) | 18.9* | (9.7) | 47.3 | (6.2) |

| Any | 78.0 | (12.4) | 62.6 | (7.7) | 21.8* | (10.3) | 53.1 | (6.6) |

| II. Prevalence of severe impairment | ||||||||

| Home | 25.9 | (15.5) | 9.4 | (4.2) | 2.9 | (3.0) | 10.1 | (3.9) |

| Work | 25.9* | (15.5) | 0.0 | -- | 0.0 | -- | 3.8 | (2.8) |

| Personal life | 6.6 | (4.7) | 5.7 | (3.6) | 1.6 | (1.7) | 4.7 | (2.2) |

| Social life | 31.7 | (13.5) | 15.9 | (6.5) | 1.6 | (1.7) | 14.3 | (4.2) |

| Any | 43.9 | (16.3) | 18.5 | (6.8) | 4.6 | (3.4) | 18.4 | (5.3) |

| (n) | (16) | (51) | (21) | (88) | ||||

Significantly difference from Binge-eating Disorder based on a .05 level, two-sided test.

Comorbidity

More than half (56.2%) of respondents with anorexia nervosa, 94.5% with bulimia nervosa, 78.9% with binge eating disorder, 63.6% with subthreshold binge eating disorder, and 76.5% with any binge eating met criteria for at least 1 of the core DSM-IV disorders assessed in the NCS-R (Table 6). Eating disorders were positively related to almost all of the core DSM-IV mood, anxiety, impulse-control, and substance use disorders after controlling for age, sex, and race-ethnicity, with 89% of the odds ratios for the association between individual eating disorders and individual comorbid conditions greater than 1.0 and 67% significant at the .05 level. The odds ratios were consistently largest, though, for bulimia nervosa, with a median (and inter-quartile range in parentheses) odds ratio of 4.7 (4.3–7.5), next highest for binge eating disorder (3.2 [2.6–3.7]) and any binge eating (3.2 [2.4–3.8]), and smaller for anorexia nervosa (2.1 [1.2–2.9]) and subthreshold binge eating disorder (2.2 [1.1–2.9]). No single class of disorders stood out as showing consistently or markedly higher comorbidity with eating disorders.

Table 6.

Lifetime co-morbidity (OR) of DSM-IV Eating Disorders with other core NCS-R/DSM-IV disorders and related behaviors1

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Anxiety disorders | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95%CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95%CI) |

| Panic disorder | 3.0 | 0.5 | (0.1–2.7) | 16.2 | 2.9* | (1.1–7.9) | 13.2 | 2.9* | (1.8–4.8) | 6.6 | 1.9 | (0.7–5.4) | 11.8 | 2.8* | (1.8–4.3) |

| Agoraphobia without panic | 4.6 | 3.2 | (0.6–17.8) | 10.8 | 8.9* | (3.0–26.2) | 6.5 | 5.2* | (1.9–13.9) | 6.0 | 5.8* | (1.5–22.1) | 6.2 | 5.6* | (2.4–12.9) |

| Specific phobia | 26.5 | 2.1* | (1.0–4.3) | 50.1 | 5.4* | (2.6–11.4) | 37.1 | 3.7* | (2.2.–6.5) | 20.7 | 2.0 | (0.9–4.3) | 32.5 | 3.3* | (2.3–4.7) |

| Social phobia | 24.8 | 2.1 | (0.9–5.2) | 41.3 | 4.7* | (2.7–8.3) | 31.9 | 3.2* | (2.1–4.9) | 26.8 | 2.5* | (1.5–4.3) | 31.0 | 3.2* | (2.4–4.3) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 7.0 | 1.0 | (0.3–3.5) | 11.8 | 1.9 | (0.9–4.1) | 11.8 | 2.0* | (1.2–3.3) | 9.9 | 2.3 | (0.6–8.6) | 11.9 | 2.2* | (1.5–3.2) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 12.0 | 1.6 | (0.5–5.7) | 45.4 | 10.2* | (5.2–20.0) | 26.3 | 5.1* | (2.8–9.4) | 5.6 | 1.1 | (0.4–2.8) | 20.2 | 4.0* | (2.6–6.1) |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder3 | 0.0 | … | … | 17.4 | 7.5* | (1.7–37.5) | 8.2 | 4.2* | (1.4–12.8) | 0.0 | … | … | 7.2 | 4.6* | (1.7–12.9) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 7.5 | 1.7 | (0.4–6.3) | 15.7 | 3.5* | (1.4–9.0) | 12.2 | 3.3* | (1.7–6.3) | 2.6 | 0.8 | (0.2–3.5) | 9.7 | 2.7* | (1.6–4.8) |

| Any anxiety disorder4 | 47.9 | 1.9 | (0.9–4.1) | 80.6 | 8.6* | (3.4–21.6) | 65.1 | 4.3* | (2.6–7.1) | 40.4 | 2.0 | (1.0–4.0) | 59.5 | 3.7* | (2.5–5.5) |

| II. Mood disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 39.1 | 2.7* | (1.3–5.7) | 50.1 | 4.3* | (1.7–10.8) | 32.3 | 2.2* | (1.3–3.7) | 17.7 | 1.3 | (0.6–2.7) | 30.9 | 2.2* | (1.6–3.2) |

| Dysthymia | 12.8 | 4.5* | (1.2–17.1) | 12.7 | 4.4* | (1.5–12.6) | 9.6 | 3.6* | (1.9–6.9) | 5.5 | 2.9 | (0.9–9.0) | 9.1 | 3.8* | (2.4–6.1) |

| Bipolar I-II disorders | 3.0 | 0.8 | (0.2–3.7) | 17.7 | 4.7* | (2.1–10.8) | 12.5 | 3.6* | (2.1–6.3) | 10.5 | 3.0 | (0.9–9.8) | 12.0 | 3.5* | (2.0–6.1) |

| Any mood disorder | 42.1 | 2.4* | (1.2–4.7) | 70.7 | 7.8* | (3.6–16.8) | 46.4 | 3.1* | (1.9–4.8) | 28.2 | 1.8 | (0.8–3.9) | 44.0 | 3.0* | (2.1–4.3) |

| III. Impulse-control disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 4.7 | 1.0 | (0.1–8.6) | 3.6 | 0.7 | (0.1–5.6) | 9.4 | 2.2* | (1.0–4.6) | 5.4 | 1.0 | (0.2–4.1) | 7.2 | 1.5 | (0.8–3.1) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder2 | 16.2 | 2.1 | (0.5–9.7) | 34.9 | 8.4* | (3.1–22.6) | 19.8 | 3.1* | (1.5–6.2) | 10.7 | 1.3 | (0.5–3.8) | 19.0 | 3.0* | (1.7–5.4) |

| Oppositional-defiant disorder2 | 10.5 | 1.4 | (0.2–8.1) | 26.9 | 5.1* | (2.1–12.5) | 18.9 | 2.9* | (1.4–6.3) | 6.9 | 0.9 | (0.2–3.5) | 15.6 | 2.4* | (1.3–4.3) |

| Conduct disorder2 | 9.8 | 1.2 | (0.2–6.7) | 26.5 | 4.7* | (2.0–10.8) | 20.0 | 2.6* | (1.4–4.8) | 7.0 | 0.5 | (0.1–2.2) | 17.2 | 1.9 | (1.0–3.8) |

| Any impulse-control disorder2 | 30.8 | 1.4 | (0.4–5.3) | 63.8 | 6.7* | (3.0–15.2) | 43.3 | 2.5* | (1.4–4.6) | 22.3 | 0.8 | (0.4–1.7) | 40.2 | 2.2* | (1.3–3.5) |

| IV. Substance use disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse or dependence | 24.5 | 2.9* | (1.2–7.2) | 33.7 | 4.6* | (2.1–10.5) | 21.4 | 2.2* | (1.2–4.0) | 30.0 | 2.3 | (1.0–5.6) | 25.8 | 2.6* | (1.9–3.7) |

| Alcohol dependence | 12.3 | 3.0* | (1.3–7.0) | 22.7 | 6.3* | (2.3–17.3) | 12.4 | 2.7* | (1.1–6.7) | 21.4 | 4.1* | (1.4–11.8) | 15.7 | 3.5* | (2.1–5.8) |

| Illicit drug abuse or dependence | 17.7 | 3.4* | (1.3–8.4) | 26.0 | 5.3* | (1.6–17.6) | 19.4 | 3.4* | (1.9–6.1) | 22.9 | 2.9* | (1.3–6.4) | 20.2 | 3.4* | (2.2–5.2) |

| Illicit drug dependence | 5.2 | 2.2 | (0.4–12.5) | 15.0 | 8.0* | (1.5–43.7) | 10.6 | 4.9* | (2.2–11.3) | 13.5 | 4.5* | (1.5–13.5) | 11.0 | 4.9* | (2.8–8.7) |

| Any substance use disorder | 27.0 | 3.0* | (1.2–7.1) | 36.8 | 4.6* | (2.0–10.8) | 23.3 | 2.1* | (1.2–3.8) | 35.5 | 2.8* | (1.2–6.5) | 28.7 | 2.8* | (1.9–3.9) |

| V. Any disorder | |||||||||||||||

| Any disorder | 56.2 | 1.3 | (0.6–3.1) | 94.5 | 17.6* | (4.5–68.4) | 78.9 | 4.2* | (2.2–7.9) | 63.6 | 2.0 | (0.8–4.6) | 76.5 | 3.7* | (2.3–6.2) |

| Exactly one | 8.4 | 0.5 | (0.1–1.8) | 6.1 | 2.8 | (0.7–11.7) | 20.2 | 2.7* | (1.1–6.5) | 9.4 | 0.7 | (0.2–2.5) | 15.9 | 1.9 | (1.0–3.8) |

| Exactly two | 14.1 | 1.4 | (0.5–4.5) | 24.0 | 19.2* | (4.2–88.6) | 9.8 | 2.2* | (1.0–4.6) | 23.5 | 3.2* | (1.0–10.0) | 15.7 | 3.2* | (1.6–6.5) |

| Three or more | 33.8 | 2.3 | (0.9–5.4) | 64.4 | 33.7* | (8.7–131.1) | 48.9 | 7.6* | (4.0–14.5) | 30.7 | 2.6* | (1.1–5.9) | 45.0 | 6.4* | (3.9–10.5) |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

A separate logistic regression equation was estimated for each comorbid disorder and a single equation was estimated for number of comorbid disorders. Each equation controlled for respondent age (in five-year intervals), sex, and race-ethnicity.

Restricted to respondents in the age range 18–44 (n=1672)

Restricted to a random sub-sample of respondents (n=1139)

OCD was coded as absent among respondents who were not assessed for this disorder.

Treatment

A majority of respondents with anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (50.0%–63.2%) received treatment for emotional problems at some time in their lives, with the most common site of treatment being the general medical sector for anorexia nervosa (45.3%) and binge eating disorder (36.3%), and the mental health specialty sector for bulimia nervosa (48.2% for psychiatrist and 48.3% for other mental health) (Table 7). However, smaller proportions sought treatment specifically for their bulimia nervosa (43.2%) or binge eating disorder (43.6%). Only 15.6% of respondents with 12-month bulimia nervosa and 28.5% with 12-month binge eating disorder received treatment for emotional problems in the 12 months before interview, with the most common site of treatment being the general medical sector, and similar proportions received 12-month treatment specifically for their bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder.

Table 7.

Age-of-onset priority of DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior with comorbid DSM-IV disorders

| Percent where eating disorders or behavior are temporally primary1 | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | |||||||||||

| % | (se) | (n) | % | (se) | (n) | % | (se) | (n) | % | (se) | (n) | % | (se) | (n) | |

| Anxiety disorders | 15.3 | (11.3) | (14) | 21.2 | (8.9) | (42) | 8.6 | (3.3) | (76) | 4.0 | (3.8) | (27) | 13.0 | (3.8) | (127) |

| Mood disorders | 70.1 | (14.8) | (14) | 64.8 | (9.1) | (36) | 34.6 | (9.1) | (58) | 39.6 | (13.5) | (20) | 48.9 | (5.9) | (100) |

| Impulse-control disorders | 0.0 | -- | (6) | 2.6 | (2.2) | (24) | 4.7 | (3.2) | (45) | 12.5 | (7.6) | (15) | 5.8 | (2.3) | (75) |

| Substance use disorders | 61.8 | (16.9) | (9) | 71.0 | (12.1) | (18) | 26.3 | (8.2) | (31) | 50.0 | (14.7) | (17) | 52.7 | (8.2) | (62) |

Based on comparison of retrospective AOO reports for eating disorders and the earliest comorbid disorder in the category

Supplemental data are available with the electronic version of this article and online at www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs/eating.php.

Discussion

In a population-based survey of American households—the first nationally representative study of eating disorders in the United States—we found estimates of lifetime prevalence for eating disorders that are broadly consistent with earlier data. However, we found a surprisingly high proportion of men with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (representing approximately one-fourth of cases of each of these disorders). By contrast, clinical and case registry studies (Fairburn and Beglin 1990; Hoek and van Hoeken 2003) report that fewer than 10% men among cases of these disorders, and population-based studies report a 15% proportion of men for anorexia nervosa (Garfinkel et al 1996) and 8%–10% of men for bulimia nervosa (Bushnell et al 1990; Garfinkel et al 1995). Note, however, that estimates from population-based studies, including ours, are unstable because they involve small numbers of men with eating disorders (no more than 5 men with either disorder in any study).

Our findings provide unique data regarding the lifetime duration of eating disorders, and the onset and duration of binge eating disorder, together with extensive information on sociodemographic features of individuals with all 5 disorders. Also, our study provides support for the common impression that the incidence of bulimia nervosa has increased significantly in the second half of the twentieth century (Kendler et al 1991; Hoek and van Hoek 2003), and it provides the first data showing a similar trend for binge eating disorder. Nevertheless, there are some data suggesting that the incidence of bulimia nervosa may be leveling off in recent years (Currin et al 2005). Whether the incidence of anorexia nervosa has increased over time is unclear and subject to debate. We failed to find a significant increase, but had little power to detect such a trend; case registry study data have yielded conflicting findings and interpretations (Fombonne, 1995; Lucas et al 1999; Hoek and van Hoeken 2003; Currin et al 2005).

We found that lifetime anorexia nervosa is associated with a low current BMI, a finding consistent with follow-up studies of clinical samples of individuals with anorexia nervosa showing that low weight often persists after resolution of the disorder (Steinhausen 2002). By contrast, binge eating disorder was found to be strongly associated with current severe obesity (BMI _ 40)—a finding also consistent with earlier reports (de Zwaan 2001; Streigel-Moore and Franko 2003; Hudson et al 2006). Although the causal pathways responsible for this latter association are unclear, shared familial factors (such as shared genes or shared family environmental exposures) are likely at least partly responsible (Hudson et al 2006).

We also assessed role impairment in all disorders except anorexia nervosa, where analysis was precluded because no 12-month cases were identified. While the majority of respondents with bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, or any binge eating reported at least some role impairment in at least 1 role domain, only 21.8% of respondents with subthreshold binge eating disorder reported any role impairment. Severe role impairment was uncommon in all conditions. It is important to note, though, that participants may possibly have under-reported role impairment due to factors such as minimization, shame, secrecy, or lack of insight stemming from the ego-syntonicity of symptoms.

Less than half of individuals with bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder had ever sought treatment for their eating disorder (a measure not assessed for anorexia nervosa), although the majority of individuals with all 3 disorders had received treatment at some point for some emotional problem. This finding, coupled with the observation that physicians infrequently assess patients for binge eating (Crow et al 2004) and often fail to recognize bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder (Johnson et al 2001), highlights the importance of querying patients about eating problems even when they do not include such problems among their presenting complaints.

We found a high prevalence of lifetime comorbid psychiatric disorders in individuals with all disorders except subthreshold binge eating disorder, although this finding was less pronounced for anorexia nervosa. These results are again generally consistent with those reported in previous population-based studies for anorexia nervosa (Garfinkel et al 1996), bulimia nervosa (Kendler et al 1991; Bushnell et al 1994; Garfinkel et al 1995; Rowe et al 2002), binge eating behavior (Vollrath et al 1992; Angst 1988; Bulik et al 2002), and regular binge eating without compensatory behaviors (Reichborn-Kjennerud et al 2004b), as well as in previous studies of clinical populations for anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder (Hudson et al 1987; Halmi et al 1991; Johnson et al 2001; Godart et al 2002; Kaye et al 2004; McElroy et al 2005). The cause for the high levels of comorbidity is not known, although there is evidence that the co-occurrence of eating disorders with mood disorders may be caused in part by common familial (Mangweth et al 2003) or genetic factors (Walters et al 1992; Wade et al 2000).

Several findings in this study are particularly noteworthy. First, we found that anorexia nervosa displayed a significantly shorter lifetime duration and lower 12-month persistence, as well as lower overall levels of comorbidity, than either bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder. These findings contrast with previous studies (Steinhausen 2002) that have conceptualized anorexia nervosa as a chronic and malignant condition. This discrepancy may be due to the fact that our population-based method identified individuals with milder cases of anorexia nervosa who might have been missed in previous follow-up studies, which were based largely on clinical samples. Alternatively, our population-based method might have missed more severe cases of anorexia nervosa, either because they were unavailable, unreachable, hospitalized, or unwilling to participate in an interview about emotional problems. Parenthetically, we would note that while we found no cases of current anorexia nervosa in our study, 15.6% of the individuals with a lifetime diagnosis of anorexia nervosa still had a current BMI of less than 18.5 at the time of interview. Indeed, these individuals (3 cases) were all below 85% of ideal body weight, thus meeting our operationalization for DSM-IV criterion A for anorexia nervosa. However, all of these individuals failed to meet at least one of the other criteria for anorexia nervosa currently—although our data did not permit an analysis of which specific criteria were lacking in individual cases. Nevertheless, these data suggest that a minority of individuals with past anorexia nervosa may continue to maintain an abnormally low body weight, even though they no longer meet full criteria for anorexia nervosa.

Our findings also provide further evidence for the clinical and public health importance of binge eating disorder. In contrast to some earlier studies suggesting that binge eating disorder might be a relatively transient condition (Cachelin et al 1999; Fairburn et al 2000), the present findings, together with those from another recent study (Pope et al, in press), suggest that this disorder is at least as chronic and stable as anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa. Binge eating disorder also appears more common than either of the other two eating disorders, exhibits substantial comorbidity with other psychiatric disorders, and is strongly associated with severe obesity. Collectively, these findings suggest that binge eating disorder represents a public health problem at least equal to that of the other 2 better-established eating disorders, adding support to the case for elevating binge eating disorder from a provisional entity to an official diagnosis in DSM-V.

Subthreshold binge eating disorder, by contrast, was found to be associated with such low impairment and comorbidity that it likely does not merit consideration for inclusion as a DSM disorder. It should be recalled, in this connection, that the main difference between subthreshold binge eating disorder and binge eating disorder is that the former lacks the criterion of distress (see Appendix Table 1 in Supplement 1). These findings suggest that the criterion of distress may be important for defining clinically meaningful forms of binge eating.

Appendix table 1.

Lifetime prevalence estimates of DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior by age and sex

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | (n) | |

| A. Males | |||||||||||

| 18–29 | 0.0 | … | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.4 | 0.7 | 2.7 | (1.0) | 4.1 | (1.2) | (288) |

| 30–44 | 0.6 | (0.4) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 2.5 | 0.8 | 2.1 | (1.0) | 4.6 | (1.3) | (403) |

| 45–59 | 0.0 | … | 1.3 | 0.9 | 2.7 | 1.2 | 1.6 | (0.8) | 4.4 | (1.6) | (339) |

| 60+ | 0.3 | (0.3) | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.9 | 0.5 | 1.1 | (0.9) | 2.3 | (1.0) | (190) |

| Total | 0.3 | (0.1) | 0.5 | 0.3 | 2.0 | 0.5 | 1.9 | (0.5) | 4.0 | (0.7) | (1220) |

| χ23 (age) | 2.51 | 5.2 | 3.8 | 1.4 | 1.9 | ||||||

| B. Females | |||||||||||

| 18–29 | 1.1 | (0.6) | 2.2 | 0.5 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 0.8 | (0.4) | 6.2 | (0.9) | (417) |

| 30–44 | 0.9 | (0.5) | 2.0 | 0.6 | 3.7 | 1.0 | 0.8 | (0.3) | 5.9 | (1.2) | (564) |

| 45–59 | 0.6 | (0.3) | 1.6 | 0.5 | 3.4 | 0.8 | 0.4 | (0.2) | 4.4 | (0.9) | (462) |

| 60+ | 0.8 | (0.8) | 0.0 | -- | 2.4 | 1.1 | 0.5 | (0.3) | 2.9 | (1.1) | (317) |

| Total | 0.9 | (0.3) | 1.5 | 0.3 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 0.6 | (0.1) | 4.9 | (0.6) | (1760) |

| χ23 (age) | 2.4 | 6.92 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 3.3 | ||||||

| C. Total | |||||||||||

| 18–29 | 0.6 | (0.3) | 1.2 | 0.3 | 2.9 | 0.5 | 1.7 | (0.5) | 5.2 | (0.7) | (705) |

| 30–44 | 0.8 | (0.3) | 1.1 | 0.3 | 3.1 | 0.7 | 1.4 | (0.5) | 5.3 | (0.9) | (967) |

| 45–59 | 0.3 | (0.2) | 1.4 | 0.5 | 3.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | (0.4) | 4.4 | (0.8) | (801) |

| 60+ | 0.6 | (0.5) | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1.7 | 0.7 | 0.8 | (0.4) | 2.7 | (0.7) | (507) |

| Total | 0.6 | (0.2) | 1.0 | 0.2 | 2.8 | 0.4 | 1.2 | (0.2) | 4.5 | (0.4) | 2980 |

| χ23 (age) | 1.8 | 5.2 | 2.5 | 2.2 | 5.2 | ||||||

Significant age difference based on a .05 level, χ23 test.

degrees of freedom = 1

degrees of freedom = 2

Note that subthreshold binge eating disorder may be defined in different ways. For example, relaxing the frequency criteria to less than the average of 2 days per week for 6 months required by DSM-IV identifies groups with characteristics similar to the full disorder (Striegel-Moore et al 2000; Crow et al 2002). We were unable, however, to evaluate these definitions due the nature of the CIDI questions, and instead defined subthreshold binge eating disorder by relaxing criteria other than frequency of binges. Thus, while our definition of subthreshold binge eating disorder does not appear to identify a clinically meaningful entity, other definitions may well do so.

Unlike subthreshold binge eating disorder, the entity “any binge eating” is associated with severe obesity, modest levels of impairment, and high levels of comorbidity with other mental disorders. These features appear to be accounted for cases of bulimia nervosa or binge eating disorder within the “any binge eating” group, given that such features are not shared by those with subthreshold binge eating disorder, and individuals with anorexia nervosa contribute only a small number of cases. The findings for any binge eating are interesting to consider in the light of findings from twin studies of binge eating. These studies have suggested that there are genetic influences on binge eating (Bulik et al 1998) and on binge eating without compensatory behaviors (Reichborn-Kjennerud et al 2004a). On the basis of our findings here, it is tempting to speculate that the heritability of binge eating behavior may be attributable primarily to cases of bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder—both of which have been shown to be familial (Strober et al 2000; Hudson et al 2006)—rather than to cases of subthreshold binge eating disorder within the group.

Several limitations of the study should be considered. First, some CIDI questions did not precisely mirror the DSM-IV criteria for the various eating disorders, as illustrated by in the diagnostic algorithms discussed in our methods section. Perhaps the most important inconsistency is that, in order to have parallel duration requirements for bulimia nervosa and for binge eating disorder, we required only 3 months of illness for a diagnosis of binge eating disorder, in contrast to the 6 months required by DSM-IV. Thus, it is possible that we may have overestimated the prevalence of binge eating disorder by including some cases with a duration of only 3 to 5 months.

Second, diagnoses were based on unvalidated, fully structured lay interviews where lifetime information was assessed retrospectively. These may be important considerations, given that an earlier version of the CIDI was found to underdiagnose eating disorders (Thornton et al 1998), possibly because some individuals minimized or denied symptoms. Version 3.0 of the CIDI was designed to reduce this sort of under-reporting by using a number of techniques developed by survey methodologists to reduce embarrassment and other psychological barriers to reporting (Kessler and Ustun 2004)—but these changes necessitated indirect assessments of loss of control and distress, as noted above. In any event, pending validation studies, it would seem prudent to think of the NCS-R estimates as lower bounds on the true prevalence of eating disorders.

Third, in our analyses of the associations between eating disorders and body weight, we possessed only current BMI, rather than maximum or minimum adult BMI, or BMI at the time of the disorder. Thus, we likely underestimated the magnitude of these associations.

Fourth, because recall of earlier experiences may diminish with age, our retrospective assessments may have overestimated the magnitude of cohort effects (Giuffra and Risch 1994). Since cohort effects and age effects are confounded, and no prospective studies have been performed over the period under study, it is not possible to assess the magnitude of this potential bias. Prospective studies will be useful to track possible cohort effects in the future.

Fifth, our results are based on the assumption that any exiting from the population available for sampling was non-informative and that there was no selection bias (in the form of non-response bias) due to sampling from available subjects; these limitations are discussed elsewhere (Hudson et al 2005). For example, the validity of our results would be threatened if the development of eating disorders rendered individuals less likely to be available for sampling, which might occur if there were a high mortality due to eating disorders, or a significant proportion of cases hospitalized at the time of sampling. Although some clinical follow-up studies have suggested substantial mortality for anorexia nervosa (Sullivan 1995; Steinhausen 2002; Keel et al 2003), data from a community case registry study (Iacovino 2004) did not find excess mortality.

Another possible threat to validity would be bias in sampling of available individuals, in that individuals with eating disorders might be more or less likely to participate. However, we carried out a non-response survey to deal with this problem, which offered a larger financial incentive ($100) to main survey nonrespondents for a short (15-min) telephone interview that assessed diagnostic stem questions. Very little evidence was found that survey respondents and non-respondents differed on stem question endorsement for the NCS-R core anxiety, mood, impulsecontrol, or substance use disorders (Kessler et al 2004b). Thus, it is likely that non-response bias for eating disorders was minimal.

Sixth, while we examined 2 provisional entities in addition to those for which criteria were provided in DSM-IV, we did not examine many other possible entities that lie within the category of Eating Disorder Not Otherwise Specified (Fairburn and Bohn, 2005)—such as subthreshold forms of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa, alternative definitions for subthreshold binge eating disorder (discussed above), purging without either bulimia nervosa or anorexia nervosa (Keel et al 2005), and night eating syndrome (Stunkard et al 2005)— because the questions in the CIDI did not permit evaluation of these conditions.

In conclusion, the lifetime prevalence of the individual eating disorders ranged from 0.6–4.5%; these disorders displayed substantial comorbidity with other DSM-IV disorders and were frequently associated with role impairment. These patterns raise concerns that such a low proportion of individuals with these disorders obtain treatment for their eating problems. As it turns out, though, a high proportion of cases did receive treatment for comorbid conditions. Thus, detection and treatment of eating disorders might be increased substantially if treatment providers queried patients about possible eating problems, even if the patients did not include such problems among their presenting complaints.

Figure 3.

Cohort-specific age-of-onset distributions for DSM-IV Bulimia Nervosa

Figure 4.

Cohort-specific age-of-onset distributions for DSM-IV Binge-Eating Disorder

Appendix table 2.

Twelve-month prevalence estimates of DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior by age and sex

| Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | (n) | |

| A. Males | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 0.0 | -- | 0.1 | (0.1) | 0.6 | (0.4) | 0.7 | (0.4) | (288) |

| 30–44 | 0.0 | -- | 0.9 | (0.4) | 0.9 | (0.4) | 1.8 | (0.6) | (403) |

| 45–59 | 0.0 | -- | 1.6 | (1.1) | 0.9 | (0.7) | 2.6 | (1.3) | (339) |

| 60+ | 0.3 | (0.3) | 0.4 | (0.4) | 0.8 | (0.8) | 1.5 | (0.9) | (190) |

| Total | 0.1 | (0.1) | 0.8 | (0.3) | 0.8 | (0.3) | 1.7 | (0.4) | (1220) |

| χ23 (age) | -- | 5.7 | 0.9 | 4.9 | |||||

| B. Females | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 0.6 | (0.3) | 2.4 | (0.7) | 0.6 | (0.4) | 3.6 | (0.7) | (417) |

| 30–44 | 0.7 | (0.3) | 1.3 | (0.4) | 0.4 | (0.2) | 2.5 | (0.6) | (564) |

| 45–59 | 0.7 | (0.4) | 1.5 | (0.6) | 0.1 | (0.1) | 2.3 | (0.7) | (462) |

| 60+ | 0.0 | -- | 1.2 | (0.6) | 0.3 | (0.2) | 1.5 | (0.6) | (317) |

| Total | 0.5 | (0.2) | 1.6 | (0.2) | 0.4 | (0.1) | 2.5 | (0.3) | (1760) |

| χ23 (age) | 1.1 | 3.1 | 1.8 | 4.0 | |||||

| C. Total | |||||||||

| 18–29 | 0.3 | (0.2) | 1.4 | (0.4) | 0.6 | (0.3) | 2.3 | (0.4) | (705) |

| 30–44 | 0.4 | (0.2) | 1.1 | (0.3) | 0.6 | (0.2) | 2.2 | (0.4) | (967) |

| 45–59 | 0.4 | (0.2) | 1.5 | (0.3) | 0.5 | (0.4) | 2.4 | (0.5) | (801) |

| 60+ | 0.1 | (0.1) | 0.8 | (0.4) | 0.5 | (0.4) | 1.5 | (0.5) | (507) |

| Total | 0.3 | (0.1) | 1.2 | (0.2) | 0.6 | (0.2) | 2.1 | (0.2) | 2980 |

| χ23 (age) | 0.9 | 1.6 | 0.1 | 1.7 | |||||

Significant age difference based on a .05 level, χ23 test.

Appendix table 3.

Estimated age-of-onset and persistence of DSM-IV eating disorders by lifetime treatment status

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Means | ||||||

| Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | Mean | (se) | |

| A. Treated | ||||||

| Age-of-onset | 17.8 | (1.1) | 24.8 | (2.3) | 25.1 | (2.0) |

| Years with episode | 1.7 | (0.3) | 8.0* | (1.9) | 12.6* | (2.3) |

| 12-month persistence | 0.0 | -- | 44.7 | (9.7) | 42.1 | (7.9) |

| B. Untreated | ||||||

| Age-of-onset | 19.5 | (0.8) | 18.1 | (1.4) | 25.6 | (1.6) |

| Years with episode | 1.8 | (0.3) | 8.6* | (2.1) | 4.9* | (0.7) |

| 12-month persistence | 0.0 | -- | 19.8 | (7.8) | 45.8 | (8.9) |

| C. Total | ||||||

| Age-of-onset | 18.9 | (0.8) | 19.7 | (1.3) | 25.4 | (1.2) |

| Years with episode | 1.7 | (0.2) | 8.3* | (1.6) | 8.1* | (1.1) |

| 12-month persistence | 0.0 | -- | 30.6 | (7.2) | 44.2 | (6.0) |

| II. Medians | ||||||

| Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | Median | (IQR) | |

|

|

|

|

||||

| A. Treated | ||||||

| Age-of-onset | 17.0 | (15.0–21.0) | 18.0* | (16.0–20.0) | 21.0* | (16.0–30.0) |

| Years with episode | 1.0 | (1.0–2.0) | 4.0* | (2.0–13.0) | 5.0* | (2.0–20.0) |

| 12-month persistence | 0.0 | -- | 0.0 | (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 | (0.0–1.0) |

| B. Untreated | ||||||

| Age-of-onset | 21.0 | (17.0–22.0) | 17.0* | (13.0–20.0) | 19.0* | (16.0–32.0) |

| Years with episode | 1.0 | (1.0–1.0) | 6.0* | (2.0–17.0) | 3.0* | (1.0–8.0) |

| 12-month persistence | 0.0 | -- | 0.0 | (0.0–0.0) | 0.0 | (0.0–1.0) |

| C. Total | ||||||

| Age-of-onset | 18.0 | (16.0–22.0) | 18.0 | (14.0–22.0) | 21.0 | (17.0–32.0) |

| Years with episode | 1.0 | (1.0–1.0) | 5.0* | (2.0–15.0) | 3.0* | (1.0–10.0) |

| 12-month persistence | 0.0 | -- | 0.0 | (0.0–1.0) | 0.0 | (0.0–1.0) |

| (n) | (23) | (52) | (115) | |||

Significantly different from Anorexia Nervosa based on a .05 level, two-sided test.

Appendix table 4.

Cross-sectional socio-demographic profile of respondents with lifetime DSM-IV eating disorders and related behavior1

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | Subthreshold Binge-eating | Any binge-eating behavior | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Race-ethnicity | ||||||||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 1.0 | (0.4–2.5) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.2) | 1.9 | (0.5–7.1) | 0.9 | (0.4–1.7) | ||

| Hispanic | 0.32 | (0.1–1.4) | 2.0 | (0.4–11.0) | 0.9 | (0.3–2.8) | 1.0 | (0.2–5.2) | 1.0 | (0.6–2.1) |

| Other | 0.5 | (0.1–3.9) | 2.0 | (0.8–4.5) | 0.5 | (0.1–2.5) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.2) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.8) |

| χ23 (p-value) | 2.7 (.259) | 3.2 (.352) | 2.8 (.425) | 1.3 (.739) | 0.8 (.839) | |||||

| Education | ||||||||||

| Less than high school | 0.5 | (0.1–2.6) | 1.3 | (0.4–4.1) | 2.1 | (0.8–5.2) | 1.9 | (0.4–10.0) | 1.8 | (1.0–3.4) |

| High school graduate | 0.8 | (0.4–1.7) | 0.4 | (0.2–0.9) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.8) | 1.7 | (0.5–6.7) | 0.9 | (0.5–1.6) |

| Some post-HS education | 1.1 | (0.4–3.3) | 1.2 | (0.6–2.7) | 1.5 | (0.8–3.1) | 2.2 | (0.7–7.0) | 1.5 | (0.9–2.4) |

| College graduate | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| χ23 (p-value) | 1.9 (.601) | 8.4* (.039) | 15.5 (.002) | 2.1 (.561) | 17.4* (.001) | |||||

| Marital status | ||||||||||

| Previously married | 1.0 | (0.2–4.1) | 1.8 | (0.8–3.9) | 1.0 | (0.5–1.8) | 0.8 | (0.3–1.7) | 1.0 | (0.7–1.6) |

| Never married | 0.4 | (0.1–2.0) | 0.2 | (0.1–0.5) | 0.8 | (0.6–1.3) | 0.6 | (0.3–1.2) | 0.7* | (0.5–0.9) |

| Married-cohabitating | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| χ22 (p-value) | 1.8 (.411) | 15.3* (.000) | 0.8 (.669) | 2.1 (.347) | 7.2* (.027) | |||||

| Employment status | ||||||||||

| Employed | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- | 1.0 | -- |

| Student | 3.7 | (0.4–37.0) | 0.6 | (0.1–5.3) | 1.2 | (0.3–5.5) | 4.2 | (0.7–24.6) | 2.0 | (0.9–4.3) |

| Homemaker | 4.3 | (1.4–12.7) | 1.0 | (0.4–2.2) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.9) | 0.7 | (0.1–3.2) | 0.7 | (0.3–1.3) |

| Retired | 7.5 | (0.4–142.1) | 1.8 | (0.2–14.8) | 0.2* | (0.0–0.7) | 0.8 | (0.2–3.6) | ||

| Other | 0.93 | (0.1–6.3) | 2.5 | (1.1–5.8) | 1.9 | (0.9–3.8) | 2.1 | (0.6–7.5) | 2.1 | (1.4–3.2) |

| χ24 (p-value) | 13.9 (.003) | 6.8 (.145) | 5.5 (.240) | 9.7 (.046) | 19.9 (.001) | |||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Controlling for age and sex in every model

Non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics were collapsed in this equation because of sparse data.

Variables Retired and Other were collapsed in this equation because of sparse data.

Table 8a.

Lifetime and 12-month treatment of DSM-IV eating disorders

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

| I. Lifetime treatment1 for any emotional problem | ||||||

| General medical | 45.3 | (12.6) | 43.9 | (11.4) | 36.3 | (5.6) |

| Psychiatrist | 29.4 | (12.8) | 48.2 | (8.1) | 33.6 | (6.3) |

| Other mental health | 34.3 | (10.2) | 48.3 | (9.9) | 35.0 | (3.2) |

| Human services | 11.7 | (7.5) | 14.9 | (3.0) | 19.9 | (4.2) |

| CAM | 26.0 | (12.1) | 21.6 | (6.1) | 19.7 | (4.1) |

| Any lifetime treatment | 50.0 | (14.6) | 63.2 | (7.8) | 51.2 | (6.5) |

| (n) | (23) | (52) | (115) | |||

| II. Twelve-month treatment1 for any emotional problem2 | ||||||

| General medical | 26.1 | (14.3) | 20.8 | (7.2) | ||

| Psychiatrist | 9.0 | (5.5) | 5.0 | (2.6) | ||

| Other mental health | 3.7 | (3.3) | 24.0 | (6.3) | ||

| Human services | 13.5 | (10.0) | 7.1 | (4.6) | ||

| CAM | 0.0 | -- | 12.4 | (5.1) | ||

| Any 12-month treatment | 15.6 | (9.4) | 28.5 | (10.7) | ||

| (n) | (16) | (51) | ||||

| III. Treatment of eating disorders | ||||||

| Lifetime | 33.8 | (14.2) | 43.2 | (9.7) | 43.6 | (6.2) |

| Twelve-month | 15.6 | (9.4) | 28.4 | (6.4) | ||

General medical treatment is treatment by a non-psychiatrist physician or nurse or other medical practitioner who is not a mental health specialist. Psychiatrist treatment is treatment by a psychiatrist. Other mental health treatment is treatment by any mental health specialist other than a psychiatrist (e.g., psychologist, psychiatric social worker). Human services treatment is treatment by a minister, priest, rabbi, or other spiritual advisor or by a caseworker in a social services agency. CAM (Complementary-alternative medical) treatment is treatment in a self-help group on treatment by an alternative medical provider (e.g., massage therapist, chiropractor).

There were no respondents with 12-month Anorexia Nervosa.

Table 8b.

Lifetime and 12-month treatment of DSM-IV eating disorders for females

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

| I. Lifetime treatment1 for any emotional problem | ||||||

| General medical | 44.2 | (12.3) | 49.4 | (10.8) | 42.2 | (6.3) |

| Psychiatrist | 30.0 | (13.7) | 40.8 | (6.6) | 33.1 | (7.0) |

| Other mental health | 24.7 | (12.1) | 56.4 | (7.7) | 38.4 | (5.4) |

| Human services | 14.6 | (9.4) | 16.3 | (6.5) | 21.3 | (6.2) |

| CAM | 20.0 | (10.7) | 24.8 | (6.9) | 24.5 | (5.5) |

| Any lifetime treatment | 37.7 | (16.8) | 59.8 | (8.1) | 52.3 | (7.2) |

| (n) | (19) | (45) | (84) | |||

| II. Twelve-month treatment1 for any emotional problem2 | ||||||

| General medical | 28.7 | (15.3) | 24.7 | (7.8) | ||

| Psychiatrist | 9.9 | (5.9) | 4.9 | (2.8) | ||

| Other mental health | 4.0 | (3.5) | 25.1 | (10.2) | ||

| Human services | 14.8 | (10.9) | 7.9 | (6.2) | ||

| CAM | 0.0 | 15.6 | (6.8) | |||

| Any 12-month treatment | 17.1 | (10.2) | 31.6 | (10.7) | ||

| (n) | (15) | (39) | ||||

| III. Treatment of eating disorders | ||||||

| Lifetime | 29.8 | (13.7) | 47.0 | (8.5) | 50.8 | (6.9) |

| Twelve-month | 17.1 | (10.2) | 31.6 | (10.7) | ||

General medical treatment is treatment by a non-psychiatrist physician or nurse or other medical practitioner who is not a mental health specialist. Psychiatrist treatment is treatment by a psychiatrist. Other mental health treatment is treatment by any mental health specialist other than a psychiatrist (e.g., psychologist, psychiatric social worker). Human services treatment is treatment by a minister, priest, rabbi, or other spiritual advisor or by a caseworker in a social services agency. CAM (Complementary-alternative medical) treatment is treatment in a self-help group on treatment by an alternative medical provider (e.g., massage therapist, chiropractor).

There were no respondents with 12-month Anorexia Nervosa.

Table 8c.

Lifetime and 12-month treatment of DSM-IV eating disorders for males

| Anorexia Nervosa | Bulimia Nervosa | Binge-eating Disorder | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | |

| I. Lifetime treatment1 for any emotional problem | ||||||

| General medical | 49.6 | (25.1) | 22.9 | (15.8) | 24.3 | (7.5) |

| Psychiatrist | 26.9 | (22.7) | 75.8 | (17.1) | 34.8 | (11.3) |

| Other mental health | 73.1 | (22.7) | 18.0 | (14.2) | 28.1 | (10.2) |

| Human services | 0.0 | -- | 9.6 | (10.1) | 17.1 | (6.9) |

| CAM | 50.2 | (25.1) | 9.6 | (10.1) | 10.1 | (5.4) |

| Any lifetime treatment | 100.0 | -- | 75.8 | (17.1) | 48.8 | (12.0) |

| (n) | (4) | (7) | (31) | |||

| II. Twelve-month treatment1 for any emotional problem2 | ||||||

| General medical | 0.0 | -- | 12.2 | (9.4) | ||

| Psychiatrist | 0.0 | -- | 5.4 | (5.5) | ||

| Other mental health | 0.0 | -- | 21.5 | (15.2) | ||

| Human services | 0.0 | -- | 5.4 | (5.5) | ||

| CAM | 0.0 | -- | 5.4 | (5.5) | ||

| Any 12-month treatment | 0.0 | -- | 21.5 | (15.2) | ||

| (n) | (1) | (12) | ||||

| III. Treatment of eating disorders | ||||||

| Lifetime | 50.2 | (25.1) | 29.1 | (19.3) | 28.9 | (9.4) |

| Twelve-month | 0.0 | -- | 21.5 | (15.2) | ||

General medical treatment is treatment by a non-psychiatrist physician or nurse or other medical practitioner who is not a mental health specialist. Psychiatrist treatment is treatment by a psychiatrist. Other mental health treatment is treatment by any mental health specialist other than a psychiatrist (e.g., psychologist, psychiatric social worker). Human services treatment is treatment by a minister, priest, rabbi, or other spiritual advisor or by a caseworker in a social services agency. CAM (Complementary-alternative medical) treatment is treatment in a self-help group on treatment by an alternative medical provider (e.g., massage therapist, chiropractor).

There were no respondents with 12-month Anorexia Nervosa.

Acknowledgments

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH; U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from the National Institute of Drug Abuse, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Grant # 044780), Eli Lilly and Company, and the John W. Alden Trust. Preparation of this report was additionally supported by OrthoMcNeil Neurologics, Inc. Collaborating NCS-R investigators include Ronald C. Kessler (Principal Investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (Co-Principal Investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (NIDA), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), T Bedirhan Ustun (World Health Organization), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or US Government. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative.

We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. These activities were supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Pan American Health Organization, the Pfizer Foundation, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, and OrthoMcNeil Neurologics, Inc. A complete list of WMH publications and instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi. Supplemental material cited in this article is available online.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4. (DSM-IV) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Angst J. The emerging epidemiology of hypomania and bipolar II disorder. J Affect Disord. 1998;50:143–151. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(98)00142-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Heritability of binge-eating and broadly defined bulimia nervosa. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;44:1210–1218. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00280-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bulik CM, Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. Medical and psychiatric morbidity in obese women with and without binge eating. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:72–78. doi: 10.1002/eat.10072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell JA, Wells JE, Hornblow AR, Oakley-Browne MA, Joyce P. Prevalence of three bulimia syndromes in the general population. Psychol Med. 1990;20:671–680. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700017190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bushnell JA, Wells JE, McKenzie JM, Hornblow AR, Oakley-Browne MA, Joyce PR. Bulimia comorbidity in the general population and in the clinic. Psychol Med. 1994;24:605–611. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700027756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cachelin FM, Striegel-Moore RH, Elder KA, Pike KM, Wilfley DE, Fairburn CG. Natural course of a community sample of women with binge eating disorder. Int J Eat Disord. 1999;25:45–54. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199901)25:1<45::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Agras WS, Halmi K, Mitchell JE, Kraemer HC. Full syndromal versus subthreshold anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder: a multicenter study. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32:309–318. doi: 10.1002/eat.10088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crow SJ, Peterson CB, Levine AS, Thuras P, Mitchell JE. A survey of binge eating and obesity treatment practices among primary care providers. Int J Eat Disord. 2004;35:348–53. doi: 10.1002/eat.10266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currin L, Schmidt U, Treasure J, Jick H. Time trends in eating disorder incidence. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:132–135. doi: 10.1192/bjp.186.2.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Zwaan M. Binge eating disorder and obesity. Int J Obesity. 2001;25:S51–S55. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Beglin SJ. Studies of the epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:401–408. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Cooper Z, Doll HA, Norman P, O’Connor M. The natural course of bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder in young women. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:659–665. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Favaro A, Ferrara S, Santonastaso P. The spectrum of eating disorders in young women: a prevalence study in a general population sample. Psychosom Med. 2004;65:701–708. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000073871.67679.d8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non–patient Edition (SCID–I/NP) New York: Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E. Anorexia nervosa: no evidence of an increase. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166:462–471. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.4.462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering C, Spegg D, Goldbloom D, Kennedy S. Should amenorrhoea be necessary for the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa? Evidence from a Canadian community sample. Br J Psychiatry. 1996;168:500–506. doi: 10.1192/bjp.168.4.500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garfinkel PE, Lin E, Goering P, Spegg C, Goldbloom DS, Kennedy S, et al. Bulimia nervosa in a Canadian community sample: prevalence and comparison subgroups. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1052–1058. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuffra LA, Risch N. Diminished recall and the cohort effect of major depression: a simulation study. Psychol Med. 1994;24:375–383. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700027355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godart NT, Flament MF, Perdereau F, Jeammet P. Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: a review. Int J Eating Disord. 2002;32:253–270. doi: 10.1002/eat.10096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halmi KA, Eckert E, Marchi P, Sampugno V, Apple R, Cohen J. Comorbidity of psychiatric diagnoses in anorexia nervosa. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1991;48:712–718. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810320036006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoek HW, van Hoeken D. Review of the prevalence and incidence of eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2003;34:383–396. doi: 10.1002/eat.10222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. 2. New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Lalonde JK, Berry JM, Pindyck LJ, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, et al. Binge eating disorder as a distinct familial phenotype in obese individuals. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:313–319. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.3.313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Pope HG, Jr, Glynn RJ. The cross–sectional cohort study: an under-utilized design. Epidemiology. 2005;16:355–359. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000158224.50593.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson JI, Pope HG, Jr, Yurgelun-Todd D, Jonas JM, Frankenburg FR. A controlled study of lifetime prevalence of affective and other psychiatric disorders in bulimic outpatients. Am J Psychiatry. 1987;144:1283–1287. doi: 10.1176/ajp.144.10.1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iacovino JR. Anorexia nervosa: a 63-year population-based survival study. J Insur Med. 2004;36:107–110. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. Health problems, impairment and illnesses associated with bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder among primary care and obstetric gynaecology patients. Psychol Med. 2001;31:1455–66. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701004640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye WH, Bulik CM, Thornton L, Barbarich N, Master K. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2215–2221. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Dorer DJ, Eddy KT, Franko D, Charatan DL, Herzog DB. Predictors of mortality in eating disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:179–183. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keel PK, Haedt A, Edler C. Purging disorder: an ominous variant of bulimia nervosa? Inter J Eat Disord. 2005;38(3):191–9. doi: 10.1002/eat.20179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, MacLean C, Neale M, Kessler R, Heath A, Eaves L. The genetic epidemiology of bulimia nervosa. AmJ Psychiatry. 1991;148:1627–1637. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.12.1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, et al. Clinical Calibration of DSM-IV Diagnoses in the World Mental Health(WMH)Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004a;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004b;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PB, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. ArchGenPsychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eschleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Trefalt E, Mangweth B, Biebl W. Binge eating disorder in females: a population-based investigation. Int J Eating Disord. 1999a;25:287–292. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199904)25:3<287::aid-eat6>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinzl JF, Traweger C, Trefalt E, Mangweth B, Biebl W. Binge eating disorder in males: a population-based investigation. Eat Weight Disord. 1999b;4:169–174. doi: 10.1007/BF03339732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leon AC, Olfson M, Portera L, Farber L, Sheehan DV. Assessing psychiatric impairment in primary care with the Sheehan Disability Scale. Int J Psychiatry Med. 1997;27:93–105. doi: 10.2190/T8EM-C8YH-373N-1UWD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucas AR, Crowson CS, O’Fallon WM, Melton LJ., 3rd The ups and downs of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eating Disord. 1999;26:397–405. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199912)26:4<397::aid-eat5>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangweth B, Hudson JI, Pope HG, Jr, Hausmann A, De Col C, Laird NM, et al. Family study of the aggregation of eating disorders and mood disorders. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1319–1323. doi: 10.1017/s0033291703008250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McElroy SL, Kotwal R, Keck PE, Jr, Akiskal HS. Comorbidity of bipolar and eating disorders: distinct or related disorders with shared dysregulations? J Affect Disord. 2005;86:107–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jr, Lalonde JK, Pindyck LJ, Walsh BT, Bulik CM, Crow SJ, McElroy SL, Rosenthal NR, Hudson JI. Binge eating disorder: a stable syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.12.2181. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM, Tambs K, Harris JR. Genetic and environmental influences on binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors: a population-based twin study. Int J Eating Disord. 2004a;36:307–314. doi: 10.1002/eat.20047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichborn-Kjennerud T, Bulik CM, Tambs K, Harris JR. Psychiatric and medical symptoms in binge eating in the absence of compensatory behaviors. Obes Res. 2004b;12:1445–1454. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute. SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis. 8.01. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe R, Pickles A, Simonoff E, Bulik CM, Silberg JL. Bulimic symptoms in the Virginia Twin Study of Adolescent Behavioral Development: correlates, comorbidity, and genetics. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;51:172–182. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01257-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinhausen HC. The outcome of anorexia nervosa in the 20th century. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1284–1293. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Striegel-Moore RH, Dohm FA, Solomon EE, Fairburn CG, Pike KM, Wilfley DE. Subthreshold binge eating disorder. Int J Eating Disord. 2000;27:270–278. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200004)27:3<270::aid-eat3>3.0.co;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streigel-Moore RH, Franko DL. Epidemiology of binge eating disorder. Int J Eating Disord. 2003;34:S19–S29. doi: 10.1002/eat.10202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strober M, Freeman R, Lampert C, Diamond J, Kaye W. Controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: evidence of shared liability and transmission of partial syndromes. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:393–401. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.3.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stunkard AJ, Allison KC, O’Reardon JP. The night eating syndrome: a progress report. Appetite. 2005;2005:182–966. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2005.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan PF. Mortality in anorexia nervosa. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1073–1074. doi: 10.1176/ajp.152.7.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton C, Russell J, Hudson J. Does the Composite International Diagnostic Interview underdiagnose the eating disorders? Int J Eat Disord. 1998;23:341–345. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(199804)23:3<341::aid-eat11>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vollrath M, Koch R, Angst J. Binge eating and weight concerns among young adults. Results from the Zurich cohort study. Br J Psychiatry. 1992;160:498–503. doi: 10.1192/bjp.160.4.498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]