Abstract

HIV-associated nephropathy is caused, in part, by direct infection of kidney epithelial cells by HIV-1. In the spectrum of pathogenic host-virus interactions, abnormal activation or suppression of host transcription factors is common. NF-κB is a necessary host transcription factor for HIV-1 gene expression, and it has been shown that NF-κB activity is dysregulated in many naturally infected cell types. We show here that renal glomerular epithelial cells (podocytes) expressing the HIV-1 genome, similar to infected immune cells, also have a dysregulated and persistent activation of NF-κB. Although podocytes produce p50, p52, RelA, RelB, and c-Rel; electrophoretic mobility shift assays and immunocytochemistry showed a predominant nuclear accumulation of p50/RelA-containing NF-κB dimers in HIV-1 expressing podocytes as compared to normal. In addition, the expression level of a transfected NF-κB reporter plasmid was significantly higher in HIVAN podocytes. The mechanism of NF-κB activation involved increased phosphorylation of IκBα, resulting in an enhanced turnover of the IκBα protein. There was no evidence for regulation by IκBβ or the alternate pathway of NF-κB activation. Altered activation of this key host transcription factor likely plays a role in the well described cellular phenotypic changes observed in HIVAN such as proliferation. Studies with inhibitors of proliferation and NF-κB suggest that NF-κB activation may contribute to the proliferative mechanism in HIVAN. In addition, since NF-κB regulates many aspects of inflammation, this dysregulation may also contribute to disease severity and progression through regulation of pro-inflammatory processes in the kidney microenvironment.

Keywords: podocyte, chronic renal disease, HIV-1, transcription

INTRODUCTION

HIV-associated nephropathy (HIVAN) is a complication of HIV/AIDS that affects approximately 1% of the seropositive population in the United States. It is a significant cause of chronic kidney disease and is currently the third leading cause of kidney failure in adult African American men (31;45). A part of the disease process is the direct infection of kidney epithelial cells including the glomerular podocyte (7;9;29;34;42). This ultimately results in injury to the podocyte and glomerular damage characterized as collapsing focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (FSGS). Podocyte injury is frequently recognized as a central event in the initiation and progression of many forms of FSGS as the podocyte is the glomerular cell type primarily responsible for synthesizing the molecular components of the glomerular filtration barrier (3;32).

The specific host-virus interactions in renal cells that initiate pathology in HIVAN are not well understood. Since this renal disease has been successfully modeled in transgenic mice (11;17;23;30) and rats (43), aspects of HIVAN pathogenesis are likely to be independent of the infection process. In these instances, host cell pathogenesis may be caused by individual viral proteins, either intracellular or extracellular, which interfere with normal cellular function. Several HIV-1 proteins such as the regulatory proteins Tat, Nef, and Vpu and the envelop protein gp120 have been shown to participate in the pathogenesis of several HIV-related syndromes (52). In HIVAN, recent reports using a transgenic mouse model have proposed that the viral protein Nef may be responsible for many aspects of renal cell dysfunction (18;19;22;53). These studies suggest that interference of normal cellular functions by individual viral proteins is central to HIVAN pathogenesis.

A well known example of viral interference in host cell function is the appropriation of host transcription factors to augment viral gene expression (21). In the HIV-1 life cycle, expression of the viral genome is dependent on the host transcriptional machinery, and HIV-1 has evolved to rely largely on NF-κB (26). NF-κB is a ubiquitous transcription factor that has a central role in mediating immune and inflammatory processes (8). The prototypic NF-κB is a dimer consisting of a DNA-binding subunit (p50) and a trans-activating subunit (p65), which are regulated by a third protein, IκB. There are multiple genes which code for the p50s (p105/p50 and p100/p52), p65s (RelA, RelB, and c-Rel) and IκBs (IκBα, IκBβ, IκBγ, IκBε, Bcl-3) which result in combinatorial diversity of not only NF-κB composition and variable DNA binding specificities to κB sites, but also distinct activation mechanisms through interaction with the different IκBs. NF-κB is an immediate early response factor because the active heterodimer is preformed in the cytoplasm, and is retained in the cytoplasm through interaction with an IκB (Figure 1). In the classic mechanism of activation, IκB is phosphorylated by IκB kinases (IKK) which targets the IκB for ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. In the alternate mechanism of activation, the IκB-like carboxy terminus of p100/p52 is phosphorylated and degraded similar to an IκB. In both pathways, this releases active heterodimers from their cytoplasmic anchors exposing a nuclear localization signal, followed by nuclear translocation and binding to target gene promoters. Thus, the key regulatory event in NF-κB activation depends on the phosphorylation and subsequent degradation of an IκB or the IκB-like portion of p100.

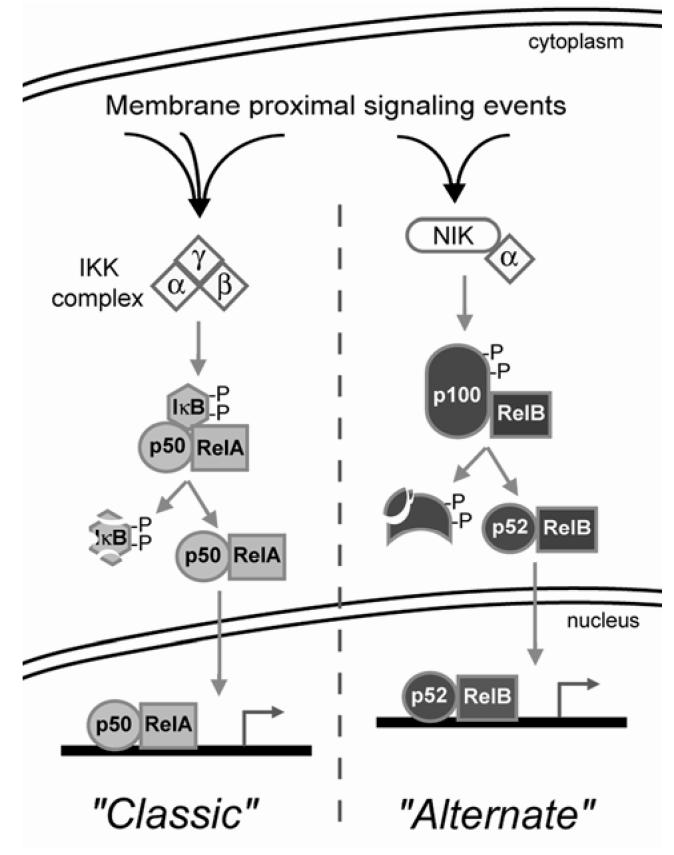

Figure 1.

Diagram of major NF-κB activation mechanisms. There are two primary mechanisms for NF-κB activation known as the “classic” and “alternate” pathways. Both can be initiated by a variety of membrane proximal signaling events which converge on the IκB kinase (IKK) complex or the NF-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) complex. See text for further details. Of importance to this study is that activation through the classic pathway involves IκB phosphorylation and degradation, followed by nuclear accumulation of RelA/p50; whereas activation through the alternate pathway is characterized by processing of p100 to p52 with the nuclear accumulation of RelB/p52.

Previously, it has been shown that HIV-infected monocytes and macrophages have a modified NF-κB activation cascade causing a sustained enhancement of NF-κB nuclear translocation (10;35;47). This persistent activation of NF-κB supports the viral life cycle, but unfortunately, is also detrimental to normal host cell function. There are over 250 host genes known to be regulated by NF-κB, and any dysregulation of NF-κB can have a significant impact on normal cell behavior. We have previously shown that, similar to infected T cells, the expression of the HIV-1 genome in kidney cells is also dependent on NF-κB (5). We now report here that similar to infected immune cells, NF-κB is persistently activated in epithelial cells from HIV-1 transgenic mouse kidneys. Using podocyte cell lines derived from normal and HIV-1 transgenic kidneys, we show that this persistent NF-κB activation involved increased phosphorylation and turnover of IκBα with a coincident increase in the nuclear appearance of p50/RelA heterodimers. There was no evidence for an IκBβ-dependent activation mechanism or processing of p100 to suggest the involvement of the alternate pathway. Preliminary studies also indicated that HIV-induced NF-κB activation was associated with increased proliferation in podocytes. In conjunction with our recent report of increased expression of other key NF-κB target genes in HIVAN (46), these studies indicate that virus-induced activation of NF-κB is an important cause of renal epithelial cell dysfunction in HIVAN pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and plasmids

The normal and HIV-1 expressing (“HIVAN”) podocyte cell lines were derived from an HIV-1 transgenic mouse model of HIVAN (30). This HIV-1 transgenic mouse model is a relevant model for the human disease process since the transgenic expression of the HIV-1 genome is similar to the integration and HIV-1 gene expression that occurs during the natural infection process. This small animal model recreates virtually all aspects of the clinical course, pathology and mortality of the human disease, and has been used extensively for molecular (1;6;33;40;41) and genetic (15) studies in host pathogenesis, and for HIVAN therapy design and testing (4;37;50). Podocyte cell lines and growth conditions have been described and studies were performed with cells differentiated for 8-10 days under nonpermissive conditions (36;48). An indicator plasmid for NF-κB activity, pNF-κB-SEAP (Clontech, Palo Alto, CA) expresses secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) under the control of a promoter that contains four NF-κB consensus sites. Control plasmids for transfection were a promoterless SEAP plasmid created by removing the 148bp HindIII/Bg/II promoter region of pTAL-SEAP (Clontech); and a pCDNA3.1-based EGFP expression plasmid provided by J. Simske (MetroHealth Medical Center, Cleveland, OH). A dominant negative mutant of IκBα, pCMV-IκBαM (Clontech), contains point mutations at serines 32 and 36 which block the phosphorylation events that trigger IκBα degradation and subsequent NF-κB activation. Podocytes were transiently transfected using FuGENE 6 (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) at a 3:1 lipid to DNA ratio. Cells were plated in serum-containing media without antibiotics and fungicides the day before transfection in 35mm dishes (105 cells/dish). Transfections were performed as recommended by the manufacturer with 1μg of plasmid DNA and with continued culture in serum-containing media. Media and cells were assayed 48 hours after transfection. Transfection efficiencies were determined as the percentage of EGFP positive cells to total cells (DAPI-stained nuclei). Due to known differences in the growth rate of the HIVAN and normal podocytes (48), transfected cells were counted at the time of assay and data were normalized to cell number. SEAP activity was assayed from conditioned media using a chemiluminescence conversion kit (Great EscAPe, BD Biosciences) as directed. Luminescence was measured using a luminometer and data are presented in relative light units (RLU) per 105 cells.

Proliferation assay and inhibitors

Proliferation was suppressed using a double thymidine block or treatment with an agent that inhibits new DNA synthesis, 5-fluoruridine (5-FU). The thymidine block was performed using a standard procedure involving an 18h incubation with 2mM thymidine, release from arrest for 9h, followed by a second block for 24h. Cells were assessed at the end of the second block using the MTS assay (Promega, Madison, WI) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Data are reported as absorbance (490nm) minus background absorbance per 105 cells. A second method used a 24h treatment with 5-FU (5μM, Calbiochem) to starve cells for dTTP, blocking cells in s-phase.

Western analysis

Western blotting was performed on whole cell extracts using a standard RIPA protein extraction protocol (provided by the primary antibody supplier) containing protease inhibitors (mini-Complete, Roche, Indianapolis, IN). Proteins were resolved on 4-16% gradient denaturing gels and electroblotted to PVDF membranes. Rabbit polyclonal antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnologies (Santa Cruz, CA) and include: RelA p65 (c-20), RelB (c-19), c-Rel (c-21), NFKB1 p50 (c-19), NFKB2 p52 (k-27), IκBα (c-21), IκBβ (c-20), IκBγ (5177c), IκBε (m-121), Bcl3 (c-14). The phospho-specific IκBα antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies (Beverly, MA), and the control antibody for α-tubulin was from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Secondary antibody (1:2000 dilution) was a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA), and detection was by chemiluminescence (ECL, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) according to manufacturer's instructions. The proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) was used at 10μM for a 1.5 hour pretreatment. The protein synthesis inhibitors anisomycin and emetine (Calbiochem) were used at 5μM for a 16 hour pretreatment. Phosphatase inhibitors (Protein Phosphatase Inhibitor Set, Calbiochem) were used at recommended concentrations.

Immunohistochemistry

Cultured cells were grown on collagen-coated glass coverslips and were fixed in cold methanol. A monoclonal antibody against PCNA (Calbiochem) was used at 1:200 dilution. Secondary antibodies (1:400 dilution) were fluorescein isothiocyanate or cyanine 3-conjugated goat anti-rabbit or goat anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch), and coverslips were mounted with aqueous mounting media followed by epi-fluorescence microscopy.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA)

Preparation of nuclear extracts, oligonucleotide labeling, binding reaction and electrophoresis conditions have been described (5). The specificity of the shifted complexes was confirmed with a competition with 100 fold molar excess of non-radioactive NF-κB oligonucleotide, and also by supershifting DNA-protein complexes with the addition of anti-NF-κB antibodies (0.5μg) to the binding reaction. Initial experiments to identify gel migration positions of heterodimer and homodimer complexes were previously established with cell lines transfected with individual NF-κB subunit proteins and have been published (5).

Statistical analysis

Graphed data are representative experiments each conducted three times, in triplicate. Data are the mean ± standard deviation with probability determined by t test (two tailed, two sample equal variance). P values used are provided in the figure legends. All EMSAs, Western blots and immunohistochemical studies were performed, at minimum, three times from independent preparations of cells or protein extracts.

RESULTS

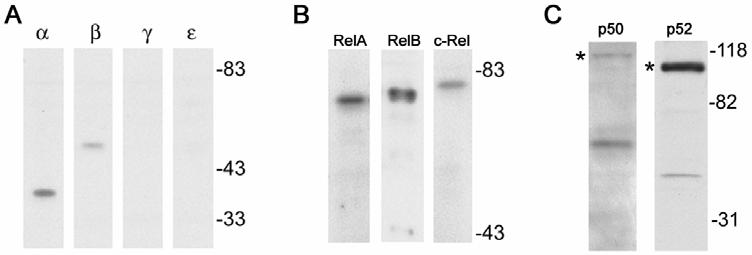

The composition of the NF-κB complex and its regulation by the various IκBs can define specific functions and mechanism of activation. Therefore, the expression pattern of all the NF-κB and IκB proteins was evaluated in podocytes. Mouse podocyte cell lines derived from normal and HIV-1 transgenic mice expressed all five of the NF-κB proteins, RelA, RelB, c-Rel, p105/p50 and p100/p52 as determined by Western blotting (Figure 2). The DNA binding subunits p50 and p52 are synthesized as larger precursors and are post-translationally processed by the 26S proteasome. The processing of p105 to p50 is a constitutive, co-translational process and thus it is typical for the mature 50kDa form to predominate. The processing of p100 to p52 is a highly regulated event involved in controlling NF-κB activation via the alternate pathway (8). Thus, in unstimulated cells it is typical to observe predominantly the full-length 100kDa form. Overall, the expression pattern of these proteins was not different between normal and HIVAN podocytes (not shown). These cells also expressed two of the inhibitor proteins, IκBα and IκBβ. There was no evidence that IκBγ and IκBε were expressed by Western blotting (Figure 2), as well as no expression of Bcl3 was observed by either Western blotting or immunocytochemistry (not shown).

Figure 2.

Identification of NF-κB proteins in normal murine podocytes. Western blotting of whole cell extracts with antibodies against all NF-κB and IκB proteins indicated that seven NF-κB proteins were expressed including RelA, RelB, c-Rel, p50, p52, IκBα, and IκBβ. IκBγ and IκBε were not detected. The proteins p50 and p52 are translated as larger precursors, p105 and p100 respectively (asterisk), and are cleaved by the proteasome to the mature form.

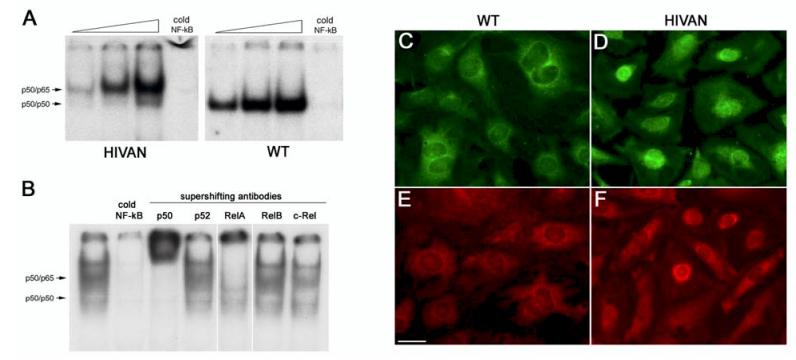

The Western blots indicated that podocytes express a variety of NF-κB proteins, however, the NF-κB transcription factor is functional only as a dimer. To determine which functional dimers form in podoctyes, EMSAs were performed using podocyte nuclear extracts and a consensus NF-κB binding site as a target DNA (Figure 3A). EMSAs using normal podocyte nuclear extracts formed a single shift complex that migrated to a known position for p50 homodimers (see methods). These p50 homodimers are commonly found in both the cytoplasm and nucleus of most cells, and it is typical to observe DNA binding p50 homodimers in unstimulated cells. However, the p50 homodimer does not contain a transactivating subunit and therefore does not activate transcription. The EMSA using nuclear extracts from HIVAN podocytes resulted in two shifted bands; a less abundant band corresponding to p50 homodimers, and a second, more abundant and higher molecular weight complex that migrated at the location of a p50/p65 heterodimer. Thus, the majority of shifting NF-κB complexes in HIVAN podocytes were p50/p65 heterodimers, which would be typical of a cell responding to an NF-κB stimulus.

Figure 3.

Difference in NF-κB activation between normal and HIVAN podocytes. A. EMSA using nuclear extracts from normal and HIVAN podocytes on a 32P-labeled oligonucleotide containing a consensus NF-κB binding site. Each panel shows a dose response of 1, 5, and 10μg of nuclear extracts, followed by a cold competition on 5μg of extract with 100 fold excess unlabeled oligonucleotide; and a supershift on 5μg of extract with an anti-RelA antibody. These panels were run on the same gel. For clarity in the figure, the gel picture was cropped eliminating unnecessary lanes and the “free” unbound oligonucleotides at the bottom of the gel. The location of p50/p50 homodimers and p50/p65 heterodimers are marked with arrows. Only transcriptionally inactive p50 homodimers were detected in the normal (WT) extracts, whereas the majority of bound complexes in the HIVAN cells were transcriptionally active p50/p65 heterodimers. Free oligonucleotide band is not shown. B. EMSA using HIVAN podocyte nuclear extracts with supershifts for the five NF-κB proteins to determine NF-κB heterodimer composition in the shifted complexes. Supershifts were detected for p50 and RelA only, indicating that the active nuclear heterodimer was composed of p50 and RelA. C-F. Expression and subcellular distribution of p50 (green) and RelA (red). Normal (C,E) and HIVAN (D,F) podocytes were immunostained for p50 and RelA and demonstrated similar overall abundance. The distribution of p50 (C) and RelA (E) in normal cells was predominantly in the cytoplasm. The distribution of p50 (D) and RelA (F) in HIVAN cells, however, was located more predominantly in the nucleus suggesting NF-κB activation. Scale bar is 20μm.

The identity of the DNA binding and transactivating proteins that were present in the shift complexes was determined also using the EMSA. Antibodies specific for the individual NF-κB proteins were added to the shift reactions (supershifts) before electrophoresis. Figure 3B shows the antibody supershifts using nuclear extracts prepared from HIVAN podocytes. The antibody to p50 recognized both the p50 homodimer and p50/p65 heterodimer, indicating that in both complexes, p50 was the DNA binding subunit. The antibody for RelA shifted the upper complex, whereas no supershifts were observed with RelB or c-Rel, indicating that the p50/p65 complex contained RelA. There was also no supershift with the p52 antibody. Thus, the activated complex in the HIVAN podocytes was the prototypical p50/RelA heterodimer, which is typically the most abundant NF-κB complex in most cells.

To confirm the EMSA binding studies, we performed immunocytochemistry with antibodies against p50 and RelA comparing the expression and subcellular distribution pattern in normal and HIVAN podocyte (Figure 3C-F). Both p50 and RelA were easily detected in both HIVAN and normal podocytes at qualitatively similar levels of expression. The expression of p50 and RelA in the normal podocytes was more cytoplasmic in distribution, although faint staining was detected in the nucleus. In the HIVAN podocytes, the distribution of both p50 and RelA became more concentrated in the nucleus in most cells, indicating NF-κB activation. Thus, both the EMSA and immunocytochemistry studies suggest that enhanced NF-κB activation of a p50/RelA complex is occurring in HIVAN podocytes.

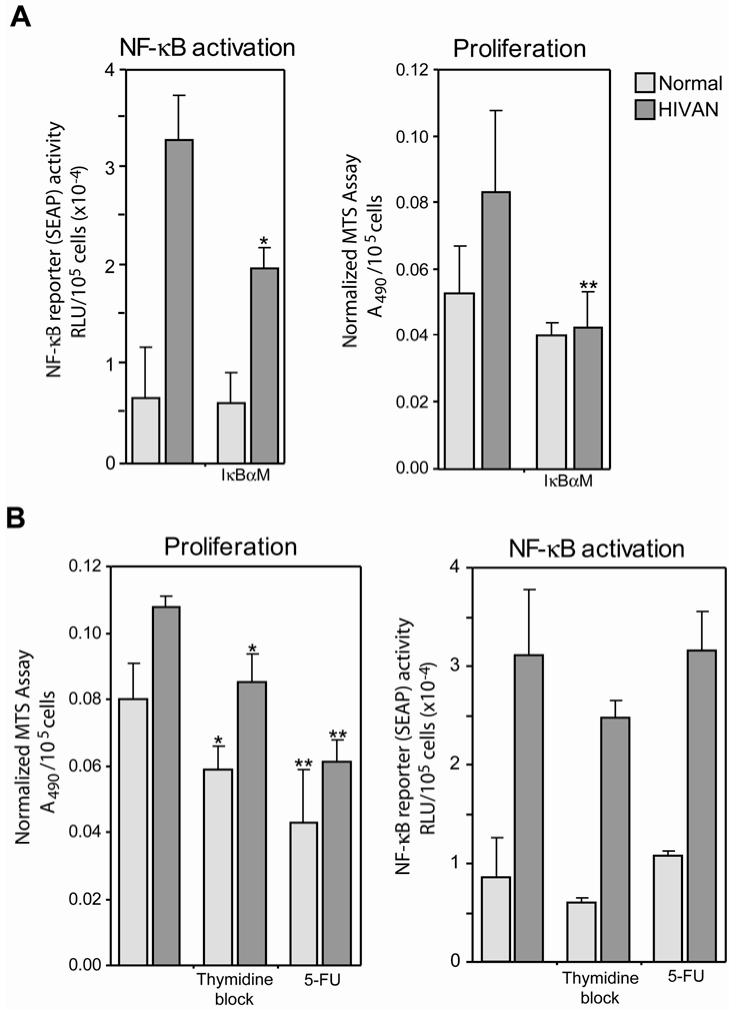

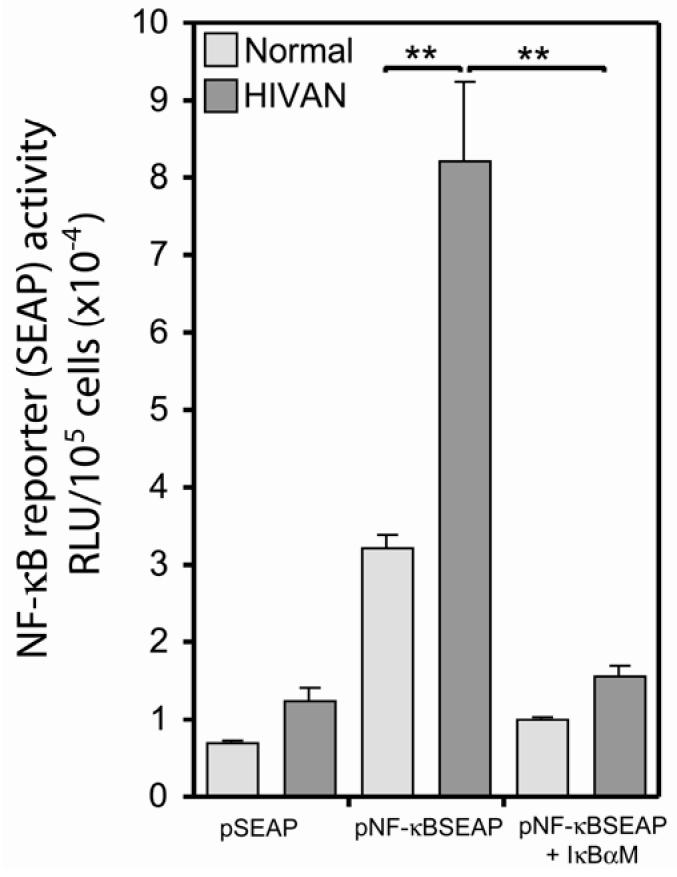

To extend these binding events to a functional assay, normal and HIVAN podocytes were transfected with an NF-κB reporter plasmid, pNF-κB-SEAP, to measure differences in NF-κB activation between the two cell lines. Figure 4 is the quantification of marker gene (SEAP) expression in normal and HIVAN podocytes transfected with either the NF-κB indicator SEAP plasmid or a control SEAP plasmid.There was a significantly higher level of NF-κB activity in the HIVAN podocytes as compared to normal. Co-transfection of the cells with an IκBα dominant negative efficiently blocked the NF-κB-dependent reporter expression, reducing reporter expression to background levels. Transient transfection efficiencies for normal and HIVAN cells were similar with an average of 22.4±2.7% (mean±standard deviation) for normal podocytes versus 23.1±1.8% for HIVAN podocytes. In addition, transfected cells were counted at the time of assay and data were normalized to cell number since there are known differences in the growth rate of the HIVAN and normal podocytes (48). The combination of this functional analysis and the in vitro binding evidence from the EMSA, indicates that HIVAN podocytes had a higher level of NF-κB activation as compared to normal cells. Since no external stimulus was provided, this difference in NF-κB activation was intrinsic to the HIVAN cells.

Figure 4.

Functional assay for NF-κB activation in podocyte cell lines. Podocytes were transfected with an NF-κB responsive reporter (“pNF-κB SEAP”) or a promoterless reporter construct (“pSEAP”) and SEAP activity was measured in conditioned media. There was a significantly higher level of NF-κB activation in the HIVAN podocytes as compared to normal. Co-transfection with an IκBα dominant negative (“IκBαM”) efficiently blocked expression from the NF-κB-dependent reporter plasmid, reducing NF-κB-dependent expression in both cell types to background levels. **P≤0.001.

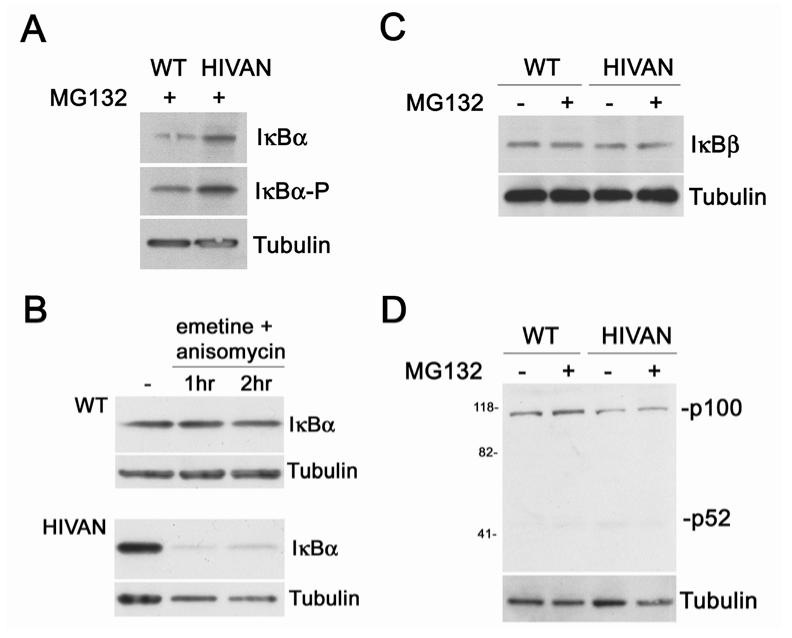

Since the key step in NF-κB activation is the phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of IκB, identifying the IκB involved in the regulation of p50/RelA will be central to defining the mechanism of activation. Figure 2 indicated that podocytes express only IκBα and IκBβ, and both these IκBs are known to interact with p50/RelA. Western blotting was used to examine the expression pattern of the IκBs in normal and HIVAN podocytes. In Figure 5A and B, two treatment strategies were used to evaluate IκBα turnover, including inhibition of proteasomal degradation with MG132 and inhibition of protein synthesis with emetine and anisomycin. These treatments were necessary since IκBα is rapidly degraded when phosphorylated, and also because NF-κB activation increases new IκBα synthesis as the IκBα gene itself is regulated by NF-κB. Thus, the level of IκBα following an NF-κB activation signal not only leads to increased IκBα degradation, but also to new IκBα protein synthesis. First, the cells were treated was with an inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, which prevents the degradation of the phosphorylated IκBα, but does not change NF-κB activation. In these treatments, more IκBα was detected in HIVAN podocytes (Figure 5A). In addition, reprobing this blot with an antibody specific for the IκBα Ser-32 phosphorylation indicated that IκBα was phosphorylated to higher degree in HIVAN podocytes as compared to normal, which also is indicative of an NF-κB activation event. The normal and HIVAN podocytes were next treated with protein synthesis inhibitors to permit visualization of IκBα degradation by the proteasome (Figure 5B). The degradation of IκBα protein was more rapid in the HIVAN podocytes, also suggesting a higher level of NF-κB activation.

Figure 5.

IκB turnover and phosphorylation. A. Western blot comparing IκBα expression in normal (WT) and HIVAN podocytes with proteasome inhibitor MG132 treatment to prevent IκBα degradation. The level of IκBα was higher in the HIVAN podocytes indicating a higher synthetic rate of the protein. Since the expression of the IκBα gene is dependent on NF-κB activation, this higher level suggests of higher degree of NF-κB activity. Reprobing this blot with an antibody specific for the Ser-32 phosphorylated form of IκB (“IκBα-P”) indicated that there was more phosphorylated IκBα in the HIVAN podocytes, also indicating a higher degree of NF-κB activity. B. Western blot of IκBα degradation in normal and HIVAN podocytes. Cells were treated with protein synthesis inhibitors and cells harvested at the given times. The IκBα protein decayed quickly in HIVAN podocytes, whereas little degradation was evident in normal podocytes. C. Western blot comparing IκBβ expression in normal (WT) and HIVAN podocytes. There was no difference in the expression of IκBβ between the two cell types, with or without the MG132 treatment. D. Western blot comparing p100/p52 expression in normal (WT) and HIVAN podocytes. Proteasomal processing of p100 to p52 would indicate activation of NF-κB through the alternate pathway. There was no change in the processing of p100 to p52 between the two cell lines. α-Tubulin was used as a loading control.

Although these studies strongly implied a role for IκBα, the expression of IκBβ and p100 processing was also studied to exclude a possible contributing role of these two alternative regulatory mechanisms. Unlike IκBα, the IκBβ gene is not regulated by NF-κB, and thus NF-κB activation results in a chronic down-regulation of IκBβ protein following a stimulus. In Figure 5C, no differences in IκBβ expression or chronic down-regulation was observed between normal and HIVAN podocytes. Similarly, the inducible, proteasomal processing of p100 to p52 was also not different between normal and HIVAN podocytes, with both showing minimal processing of the p100 form (Figure 5D). This would indicate that the alternate pathway was likely not participating in the observed NF-κB activation. In summary, these studies indicated that the increased activation of p50/RelA in HIVAN podocytes was due to an increased phosphorylation and turnover of IκBα, and did not appear to involve mechanisms involving IκBβ or p100 processing.

Since a central pathological finding in HIVAN is epithelial cell proliferation, we investigated a possible connection between podocyte proliferation and NF-κB activation. In two sets of studies, NF-κB activation was inhibited followed by an assay for proliferation, as well as the converse study, in which proliferation was inhibited and its effect on NF-κB activity determined. In Figure 6A, NF-κB activity was significantly reduced by co-transfection with a dominant negative inhibitor of IκBα (“IκBαM”). In this study, cell proliferation, measured concurrently with the NF-κB assay, also was significantly reduced. In the converse experiment (Figure 6B), however, inhibition of proliferation did not have a similar effect on NF-κB activity. In this study, proliferation was reduced using two methods, a double thymidine block and treatment with 5-FU. Testing dose and treatment length variations of both blocking protocols were unable to fully inhibit proliferation in the podocytes, however statistically significant reductions in proliferation were achieved, and the 5-FU treatment reduced proliferation to a level comparable to the level achieved with NF-κB inhibition. The IC50 for 5-FU with regard to suppression of podocyte proliferation was determined using a standard dose response curve (1nM to 1mM) and found to be 5μM (data not shown). Treatments at the IC50 for 24h did not result in significant cell death and therefore appeared to be below the apoptotic threshold for this treatment protocol. Although both treatments reduced proliferation there was no similar reduction in NF-κB activity in the HIVAN cells. In summary, it appeared that changes in the level of NF-κB activation had an impact on proliferation, suggesting a possible stimulatory effect by NF-κB. On the other hand, proliferation itself did not appear to be a driving force for NF-κB activation, and may suggest a possible sequence of events in which NF-κB activation could be a contributing stimulus for proliferation in HIVAN.

Figure 6.

Relationship between NF-κB activation and cellular proliferation. A. Suppression of NF-κB reduced HIV-induced proliferation. Cells were transfected with a dominant negative inhibitor of IκBα (“IκBαM”) to suppress NF-κB activation, followed by assay for both proliferation and NF-κB activity (*P<0.05, **P<0.01 compared to untreated). B. Suppression of proliferation does not change HIV-induced NF-κB activation. Cells were treated with either a thymidine block or 5-FU to suppress proliferation, followed by assay for both proliferation and NF-κB activity (*P<0.05, **P<0.005 compared to untreated). [The total level of SEAP activity was proportionally lower in all samples as compared with the data in Figure 4 due to a media change concurrent with drug or second thymidine application to eliminate SEAP produced prior to treatment.]

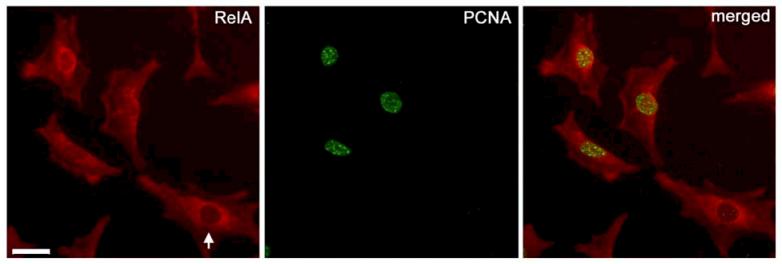

NF-κB activation was also associated with the expression of PCNA, a marker for actively proliferating cells. As shown in Figure 4, HIVAN cells exhibited greater nuclear accumulation of RelA (an indication of NF-κB activation) as compared to normal cells. In Figure 7, PCNA localization was associated with cells that had nuclear staining for RelA; whereas cells without evidence of nuclear translocation of RelA were negative for PCNA (Figure 7, arrow). This co-localization of PCNA positive cells with nuclear RelA would suggest that NF-κB activation is associated with actively proliferating cells.

Figure 7.

Nuclear NF-κB RelA localization is associated with PCNA positive cells. Cultured podocytes were co-localized with a marker of proliferation, PCNA (green), and the NF-κB p65 subunit RelA (red). Nuclear accumulation of RelA, an indication of NF-κB activation, was associated with nuclear PCNA staining. Cells without nuclear RelA localization (arrow) did not exhibit abundant nuclear PCNA staining. Scale bar is 20μm.

DISCUSSION

The consequences of chronically dysregulated NF-κB activation in renal epithelial cells likely contributes to HIVAN pathogenesis from not only enhancement of viral gene expression, but also through the dysregulation of host genes. Previous studies and expression array screens comparing normal and transgenic mouse kidneys or cell lines have shown that a number of direct NF-κB target genes are altered in HIVAN. These include the up-regulation of; cyclin D1, calcyclin, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1, intracellular adhesion molecule-1, fibronectin, vimentin, Fas, Fas ligand, and major histocompatibility class I heavy chain (37;38;44;46). For some of these, connections could be inferred from the NF-κB target gene and known pathogenic events in HIVAN. Our recent studies have shown a direct role for NF-κB in regulating the expression of the key pro-apoptotic genes, Fas and Fas ligand, as a mechanism for renal epithelial apoptosis in HIVAN (46). As would be expected, some of these genes also are associated with normal immune responses. However, little mechanistic information is known about the contributing role of NF-κB-regulated immune activation or inflammation to the overall pathogenic process in HIVAN.

Indirect evidence exists that would suggest NF-κB-regulated immune responses may have a contributing role in HIVAN pathogenesis. Prior to the era of highly active anti-retroviral therapy, attempts to treat HIVAN patients employed corticosteroids with some success (12;51;54). An important part of the anti-inflammatory action of corticosteroids is through the suppression of NF-κB (14). In these patients, improvements in renal function seemed to parallel the resolution of tubular interstitial damage and reduction in immune cell infiltrates. It is well known that HIV-1 infection is associated with a profound, systemic dysregulation of cytokines, and it has been proposed that a similar cytokine dysregulation may occur in the kidney microenvironment (27;28). In addition, a recent study by Heckmann et al. (20) treated an HIV-1 transgenic mouse model with an inhibitor of IKK2, a kinase that phosphorylates the IκBs. In this study they found that treated animals had reduced pro-inflammatory cytokine production, reduced kidney immune cell infiltrates, and an overall improved renal pathology. The treatment, however, did not block the disease process entirely. This would be consistent with our earlier studies that demonstrated expression of HIV-1 genes in kidney cells was required for disease, and that the renal disease could not be initiated by the dysregulated cytokine milieu alone (6). These observations in total suggest that direct HIV-1 infection and expression of viral proteins in renal cells is required for disease. It also suggests that NF-κB activation, as a direct result of renal cell infection, may cause the renal expression of pro-inflammatory agents or may enhance immune cell recruitment, and contribute to the overall disease severity or progression.

The preliminary studies presented here would suggest that NF-κB activation and proliferation in HIVAN are linked, and that NF-κB may be contributing to a proproliferative mechanism. NF-κB activation and IκB phosphorylation are hallmarks of diseases characterized by excessive proliferation such as chronic inflammation and cancer (13). NF-κB is know to control both aspects of cell cycle progression as well as be stimulated by molecules active during the cell cycle, forming a necessary integration of gene transcription and the cell cycle (25;39). One possible connection between NF-κB activation and the proliferative defect in HIVAN may be through the transcriptional regulation of key cell cycle regulators such as D type cyclins. Cyclin D1, as well as other cyclins and cyclin dependent kinases, have been shown to be altered in HIVAN and the other collapsing glomerulopathies (2;16;38;49). Cyclin D1 is known to be regulated by NF-κB, and since cyclin D1 protein is degraded with each cell cycle, the level of cyclin D1 is largely controlled by new transcription (25). Additional studies would be needed to establish a direct relationship between NF-κB activation and cyclin D1 expression in HIVAN.

The contribution of an IκBα-regulated p50/RelA complex as the dysregulated NF-κB in renal epithelial cells would be consistent with observations in other HIV-1 infected cells types, and thus this may be a common mechanism of viral interference in HIV-1 permissive cell types. Future studies will need to identify the upstream kinases that signal to the IKK complex. Identifying these upstream kinases also may lead to the identification of the viral protein(s) that induce the persistent NF-κB activation, as there will likely be a direct link or interaction between a key signaling pathway and the viral protein. Recent studies have implicated Nef as candidate viral protein that participates in the proliferative and dedifferentiation phenotypes in HIVAN glomerular disease through activation of Src-kinase (19). Studies in other cell types have found that Nef also has a stimulatory effect on several transcription factors including NF-κB, and thus Nef may also contribute to this aspect of renal cell dysfunction in HIVAN (24).

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that HIV-1 expression in renal epithelial cells causes a dysregulation in NF-κB activation. This HIV-induced activation was dependent on IκBα phosphorylation and degradation, suggesting the involvement of the classic pathway of NF-κB activation. This activation appeared to be linked to proliferation, a significant pathogenic phenotype of podocytes in HIVAN. Since NF-κB has many host gene targets involved in mediating immune and inflammatory processes, this dysregulation will likely have many pathogenic effects such as proliferation and apoptosis (46) of infected renal cells, but also possibly adjacent, non-infected cells through the secretion of local-acting cytokines. Identifying both the mechanism of NF-κB activation and its role in HIVAN pathogenesis may put forward new therapeutic strategies for HIVAN treatment. In addition, understanding NF-κB's role in regulating inflammatory processes in the kidney also may have application to the management of other forms of chronic renal disease that include an inflammatory component.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Drs. John Sedor and Michael J. Ross for helpful comments and critical review of the manuscript, and Dr. Jeffrey Simske for providing the EGFP expression plasmid. This work was supported by NIH grant DK61395.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barisoni L, Kriz W, Mundel P, D'Agati V. The dysregulated podocyte phenotype: a novel concept in the pathogenesis of collapsing idiopathic focal segmental glomerulosclerosis and HIV-associated nephropathy. J Am Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:51–61. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V10151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barisoni L, Mokrzycki M, Sablay L, Nagata M, Yamase H, Mundel P. Podocyte cell cycle regulation and proliferation in collapsing glomerulopathies. Kidney Int. 2000;58:137–143. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barisoni L, Mundel P. Podocyte biology and the emerging understanding of podocyte diseases. Am.J.Nephrol. 2003;23:353–360. doi: 10.1159/000072917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird JE, Durham SK, Giancarli MR, Gitlitz PH, Pandya DG, Dambach DM, Mozes MM, Kopp JB. Captopril prevents nephropathy in HIV-transgenic mice. J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 1998;9:1441–1447. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V981441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruggeman LA, Adler SH, Klotman PE. Nuclear factor-kappa B binding to the HIV-1 LTR in kidney: implications for HIV-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2001;59:2174–2181. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bruggeman LA, Dikman S, Meng C, Quaggin SE, Coffman TM, Klotman PE. Nephropathy in human immunodeficiency virus-1 transgenic mice is due to renal transgene expression. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:84–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI119525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bruggeman LA, Ross MD, Tanji N, Cara A, Dikman S, Gordon RE, Burns GC, D'Agati VD, Winston JA, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. Renal epithelium is a previously unrecognized site of HIV-1 infection. J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 2000;11:2079–2087. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V11112079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen LF, Greene WC. Shaping the nuclear action of NF-kappaB. Nat.Rev.Mol.Cell Biol. 2004;5:392–401. doi: 10.1038/nrm1368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen AH, Sun NC, Shapshak P, Imagawa DT. Demonstration of human immunodeficiency virus in renal epithelium in HIV-associated nephropathy. Modern Pathol. 1989;2:125–128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeLuca C, Roulston A, Koromilas A, Wainberg MA, Hiscott J. Chronic human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection of myeloid cells disrupts the autoregulatory control of the NF-kappaB/Rel pathway via enhanced IkappaBalpha degradation. J.Virol. 1996;70:5183–5193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5183-5193.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dickie P, Roberts A, Uwiera R, Witmer J, Sharma K, Kopp JB. Focal glomerulosclerosis in proviral and c-fms transgenic mice links Vpr expression to HIV-associated nephropathy. Virology. 2004;322:69–81. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eustace JA, Nuermberger E, Choi M, Scheel PJ, Jr., Moore R, Briggs WA. Cohort study of the treatment of severe HIV-associated nephropathy with corticosteroids. Kidney Int. 2000;58:1253–1260. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Foo SY, Nolan GP. NF-kappaB to the rescue: RELs, apoptosis and cellular transformation. Trends Genet. 1999;15:229–235. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(99)01719-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Funder JW. Glucocorticoid and mineralocorticoid receptors: biology and clinical relevance. Annu.Rev.Med. 1997;48:231–240. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.48.1.231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gharavi AG, Ahmad T, Wong RD, Hooshyar R, Vaughn J, Oller S, Frankel RZ, Bruggeman LA, D'Agati VD, Klotman PE, Lifton RP. Mapping a locus for susceptibility to HIV-1-associated nephropathy to mouse chromosome 3. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2004;101:2488–2493. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308649100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gherardi D, D'Agati V, Chu TH, Barnett A, Gianella-Borradori A, Gelman IH, Nelson PJ. Reversal of collapsing glomerulopathy in mice with the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor CYC202. J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 2004;15:1212–1222. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000124672.41036.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hanna Z, Kay DG, Cool M, Jothy S, Rebai N, Jolicoeur P. Transgenic mice expressing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 in immune cells develop a severe AIDS-like disease. J Virol. 1998;72:121–32. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.121-132.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hanna Z, Kay DG, Rebai N, Guimond A, Jothy S, Jolicoeur P. Nef harbors a major determinant of pathogenicity for an AIDS-like disease induced by HIV-1 in transgenic mice. Cell. 1998;95:163–175. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81748-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.He JC, Husain M, Sunamoto M, D'Agati VD, Klotman ME, Iyengar R, Klotman PE. Nef stimulates proliferation of glomerular podocytes through activation of Src-dependent Stat3 and MAPK1,2 pathways. J.Clin.Invest. 2004;114:643–651. doi: 10.1172/JCI21004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heckmann A, Waltzinger C, Jolicoeur P, Dreano M, Kosco-Vilbois MH, Sagot Y. IKK2 inhibitor alleviates kidney and wasting diseases in a murine model of human AIDS. Am.J.Pathol. 2004;164:1253–1262. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63213-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hiscott J, Kwon H, Genin P. Hostile takeovers: viral appropriation of the NF-kappaB pathway. J.Clin.Invest. 2001;107:143–151. doi: 10.1172/JCI11918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Husain M, Gusella GL, Klotman ME, Gelman IH, Ross MD, Schwartz EJ, Cara A, Klotman PE. HIV-1 Nef induces proliferation and anchorage-independent growth in podocytes. J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 2002;13:1806–1815. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000019642.55998.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jolicoeur P, Kay DG, Cool M, Jothy S, Rebai N, Hanna Z. A novel mouse model of HIV-1 disease. Leukemia. 1999;13(Suppl 1):78–80. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2401293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Joseph AM, Kumar M, Mitra D. Nef: “necessary and enforcing factor” in HIV infection. Curr.HIV.Res. 2005;3:87–94. doi: 10.2174/1570162052773013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joyce D, Albanese C, Steer J, Fu M, Bouzahzah B, Pestell RG. NF-kappaB and cell-cycle regulation: the cyclin connection. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2001;12:73–90. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(00)00018-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Karn J. Tackling Tat. J.Mol.Biol. 1999;293:235–254. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kimmel PL. HIV-associated nephropathy: virologic issues related to renal sclerosis. Nephrol.Dial.Transplant. 2003;18(Suppl 6):vi59–63. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kimmel PL, Cohen DJ, Abraham AA, Bodi I, Schwartz AM, Phillips TM. Upregulation of MHC class II, interferon-alpha and interferon-gamma receptor protein expression in HIV-associated nephropathy. Nephrol.Dial.Transplant. 2003;18:285–292. doi: 10.1093/ndt/18.2.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kimmel PL, Ferreira-Centeno A, Farkas-Szallasi T, Abraham AA, Garrett CT. Viral DNA in microdissected renal biopsy tissue from HIV infected patients with nephrotic syndrome. Kidney International. 1993;43:1347–52. doi: 10.1038/ki.1993.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kopp JB, Klotman ME, Adler SH, Bruggeman LA, Dickie P, Marinos NJ, Eckhaus M, Bryant JL, Notkins AL, Klotman PE. Progressive glomerulosclerosis and enhanced renal accumulation of basement membrane components in mice transgenic for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genes. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 1992;89:1577–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.5.1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kopp JB, Winkler C. HIV-associated nephropathy in African Americans. Kidney Int.Suppl. 2003:S43–S49. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.63.s83.10.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kriz W, Lemley KV. The role of the podocyte in glomerulosclerosis. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens. 1999;8:489–497. doi: 10.1097/00041552-199907000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis W. Use of the transgenic mouse in models of AIDS cardiomyopathy. Aids. 2003;17(Suppl 1):S36–45. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200304001-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marras D, Bruggeman LA, Gao F, Tanji N, Mansukhani MM, Cara A, Ross MD, Gusella GL, Benson G, D'Agati VD, Hahn BH, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. Replication and compartmentalization of HIV-1 in kidney epithelium of patients with HIV-associated nephropathy. Nat.Med. 2002;8:522–526. doi: 10.1038/nm0502-522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McElhinny JA, MacMorran WS, Bren GD, Ten RM, Israel A, Paya CV. Regulation of I kappa B alpha and p105 in monocytes and macrophages persistently infected with human immunodeficiency virus. J.Virol. 1995;69:1500–1509. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.3.1500-1509.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mundel P, Reiser J, Zuniga Mejia BA, Pavenstadt H, Davidson GR, Kriz W, Zeller R. Rearrangements of the cytoskeleton and cell contacts induce process formation during differentiation of conditionally immortalized mouse podocyte cell lines. Exp Cell Res. 1997;236:248–258. doi: 10.1006/excr.1997.3739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nelson PJ, D'Agati VD, Gries JM, Suarez JR, Gelman IH. Amelioration of nephropathy in mice expressing HIV-1 genes by the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor flavopiridol. J.Antimicrob.Chemother. 2003;51:921–929. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson PJ, Sunamoto M, Husain M, Gelman IH. HIV-1 expression induces cyclin D1 expression and pRb phosphorylation in infected podocytes: cell-cycle mechanisms contributing to the proliferative phenotype in HIV-associated nephropathy. BMC.Microbiol. 2002;2:e26. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Perkins ND, Felzien LK, Betts JC, Leung K, Beach DH, Nabel GJ. Regulation of NF-kappaB by cyclin-dependent kinases associated with the p300 coactivator. Science. 1997;275:523–527. doi: 10.1126/science.275.5299.523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Petermann A, Hiromura K, Pippin J, Blonski M, Couser WG, Kopp J, Mundel P, Shankland SJ. Differential expression of d-type cyclins in podocytes in vitro and in vivo. Am.J.Pathol. 2004;164:1417–1424. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63228-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ray PE, Bruggeman LA, Weeks BS, Kopp JB, Bryant JL, Owens JW, Notkins AL, Klotman PE. bFGF and its low affinity receptors in the pathogenesis of HIV-associated nephropathy in transgenic mice. Kidney Int. 1994;46:759–72. doi: 10.1038/ki.1994.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ray PE, Liu XH, Henry D, Dye L, Xu L, Orenstein JM, Schuztbank TE. Infection of human primary renal epithelial cells with HIV-1 from children with HIV-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 1998;53:1217–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1998.00900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ray PE, Liu XH, Robinson LR, Reid W, Xu L, Owens JW, Jones OD, Denaro F, Davis HG, Bryant JL. A novel HIV-1 transgenic rat model of childhood HIV-1-associated nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2003;63:2242–2253. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ross MD, Bruggeman LA, Hanss B, Sunamoto M, Marras D, Klotman ME, Klotman PE. Podocan, a novel small leucine-rich repeat protein expressed in the sclerotic glomerular lesion of experimental HIV-associated nephropathy. J.Biol.Chem. 2003;278:33248–33255. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301299200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ross MJ, Klotman PE. HIV-associated nephropathy. Aids. 2004;18:1089–1099. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200405210-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ross MJ, Martinka S, D'Agati VD, Bruggeman LA. NF-κB regulates Fas-mediated apoptosis in HIV-associated nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2005:2403–2411. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Roulston A, Lin R, Beauparlant P, Wainberg MA, Hiscott J. Regulation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 and cytokine gene expression in myeloid cells by NF-kappa B/Rel transcription factors. Microbiol.Rev. 1995;59:481–505. doi: 10.1128/mr.59.3.481-505.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz EJ, Cara A, Snoeck H, Ross MD, Sunamoto M, Reiser J, Mundel P, Klotman PE. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 induces loss of contact inhibition in podocytes. J.Am.Soc.Nephrol. 2001;12:1677–1684. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V1281677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shankland SJ, Eitner F, Hudkins KL, Goodpaster T, D'Agati V, Alpers CE. Differential expression of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitors in human glomerular disease: role in podocyte proliferation and maturation. Kidney Int. 2000;58:674–683. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.00213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shirai A, Klinman DM. Immunization with recombinant gp160 prolongs the survival of HIV-1 transgenic mice. AIDS Res.Hum.Retroviruses. 1993;9:979–983. doi: 10.1089/aid.1993.9.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith MC, Austen JL, Carey JT, Emancipator SN, Herbener T, Gripshover B, Mbanefo C, Phinney M, Rahman M, Salata RA, Weigel K, Kalayjian RC. Prednisone improves renal function and proteinuria in human immunodeficiency virus-associated nephropathy. Am.J.Med. 1996;101:41–48. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(96)00065-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stevenson M. HIV-1 pathogenesis. Nat.Med. 2003;9:853–860. doi: 10.1038/nm0703-853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sunamoto M, Husain M, He JC, Schwartz EJ, Klotman PE. Critical role for Nef in HIV-1-induced podocyte dedifferentiation. Kidney Int. 2003;64:1695–1701. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Winston JA, Burns GC, Klotman PE. Treatment of HIV-associated nephropathy. Semin.Nephrol. 2000;20:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]