Abstract

Objective—To compare prospectively the prognostic accuracy of a 50% decrease in ST segment elevation on standard 12-lead electrocardiograms (ECGs) recorded at 60, 90, and 180 minutes after thrombolysis initiation in acute myocardial infarction. Design—Consecutive sample prospective cohort study. Setting—A single coronary care unit in the north of England. Patients—190 consecutive patients receiving thrombolysis for first acute myocardial infarction. Interventions—Thrombolysis at baseline. Main outcome measures—Cardiac mortality and left ventricular size and function assessed 36 days later. Results—Failure of ST segment elevation to resolve by 50% in the single lead of maximum ST elevation or the sum ST elevation of all infarct related ECG leads at each of the times studied was associated with a significantly higher mortality, larger left ventricular volume, and lower ejection fraction. There was some variation according to infarct site with only the 60 minute ECG predicting mortality after inferior myocardial infarction and only in anterior myocardial infarction was persistent ST elevation associated with worse left ventricular function. The analysis of the lead of maximum ST elevation at 60 minutes from thrombolysis performed as well as later ECGs in receiver operating characteristic curves for predicting clinical outcome. Conclusion—The standard 12-lead ECG at 60 minutes predicts clinical outcome as accurately as later ECGs after thrombolysis for first acute myocardial infarction. Keywords: myocardial infarction; thrombolysis; ST segment elevation

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (141.4 KB).

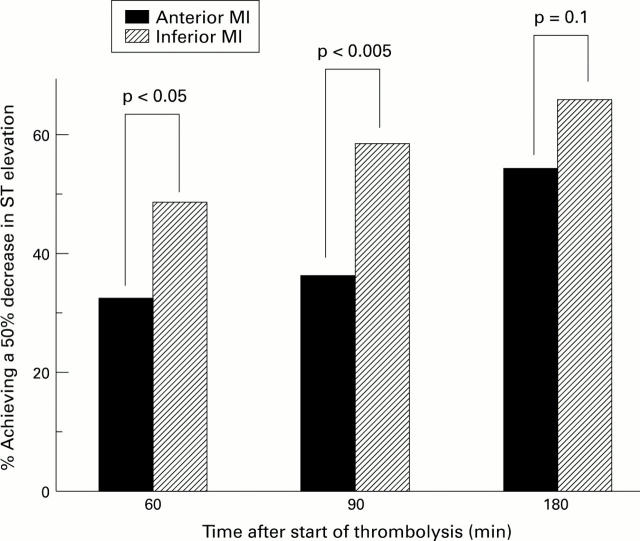

Figure 1 .

Resolution of ST elevation in anterior and inferior MI within 180 minutes of initiating thrombolysis.

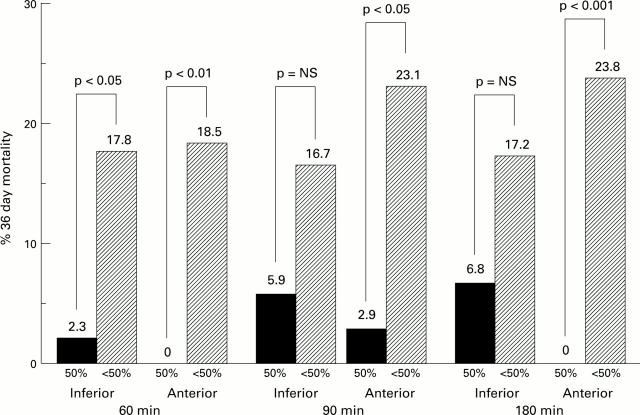

Figure 2 .

Cardiac mortality at 36 days according to 50% ST segment change in anterior and inferior myocardial.

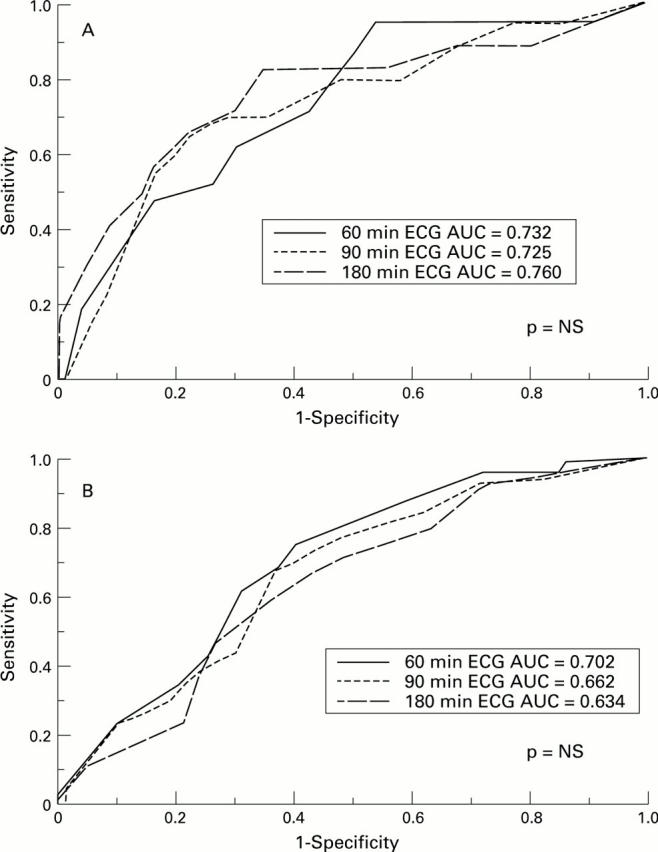

Figure 3 .

ROC curves of clinical outcome in terms of (A) cardiac mortality and (B) poor LV systolic function (LVEF < 0.4) at 36 days.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barbash G. I., Reiner J., White H. D., Wilcox R. G., Armstrong P. W., Sadowski Z., Morris D., Aylward P., Woodlief L. H., Topol E. J. Evaluation of paradoxic beneficial effects of smoking in patients receiving thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: mechanism of the "smoker's paradox" from the GUSTO-I trial, with angiographic insights. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue-Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Nov 1;26(5):1222–1229. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00299-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbash G. I., Roth A., Hod H., Miller H. I., Rath S., Har-Zahav Y., Modan M., Seligsohn U., Battler A., Kaplinsky E. Rapid resolution of ST elevation and prediction of clinical outcome in patients undergoing thrombolysis with alteplase (recombinant tissue-type plasminogen activator): results of the Israeli Study of Early Intervention in Myocardial Infarction. Br Heart J. 1990 Oct;64(4):241–247. doi: 10.1136/hrt.64.4.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger P. B., Ryan T. J. Inferior myocardial infarction. High-risk subgroups. Circulation. 1990 Feb;81(2):401–411. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.81.2.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braunwald E. The open-artery theory is alive and well--again. N Engl J Med. 1993 Nov 25;329(22):1650–1652. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199311253292211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doevendans P. A., Gorgels A. P., van der Zee R., Partouns J., Bär F. W., Wellens H. J. Electrocardiographic diagnosis of reperfusion during thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1995 Jun 15;75(17):1206–1210. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(99)80763-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez A. R., Sequeira R. F., Chakko S., Correa L. F., de Marchena E. J., Chahine R. A., Franceour D. A., Myerburg R. J. ST segment tracking for rapid determination of patency of the infarct-related artery in acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Sep;26(3):675–683. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00208-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- French J. K., Williams B. F., Hart H. H., Wyatt S., Poole J. E., Ingram C., Ellis C. J., Williams M. G., White H. D. Prospective evaluation of eligibility for thrombolytic therapy in acute myocardial infarction. BMJ. 1996 Jun 29;312(7047):1637–1641. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7047.1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J. A method of comparing the areas under receiver operating characteristic curves derived from the same cases. Radiology. 1983 Sep;148(3):839–843. doi: 10.1148/radiology.148.3.6878708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A., McNeil B. J. The meaning and use of the area under a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve. Radiology. 1982 Apr;143(1):29–36. doi: 10.1148/radiology.143.1.7063747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley J. A. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) methodology: the state of the art. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1989;29(3):307–335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hohnloser S. H., Zabel M., Kasper W., Meinertz T., Just H. Assessment of coronary artery patency after thrombolytic therapy: accurate prediction utilizing the combined analysis of three noninvasive markers. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1991 Jul;18(1):44–49. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(10)80215-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy J. W. Optimal management of acute myocardial infarction requires early and complete reperfusion. Circulation. 1995 Apr 1;91(7):1905–1907. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.7.1905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krucoff M. W., Croll M. A., Pope J. E., Granger C. B., O'Connor C. M., Sigmon K. N., Wagner B. L., Ryan J. A., Lee K. L., Kereiakes D. J. Continuous 12-lead ST-segment recovery analysis in the TAMI 7 study. Performance of a noninvasive method for real-time detection of failed myocardial reperfusion. Circulation. 1993 Aug;88(2):437–446. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.88.2.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krucoff M. W., Green C. E., Satler L. F., Miller F. C., Pallas R. S., Kent K. M., Del Negro A. A., Pearle D. L., Fletcher R. D., Rackley C. E. Noninvasive detection of coronary artery patency using continuous ST-segment monitoring. Am J Cardiol. 1986 Apr 15;57(11):916–922. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(86)90730-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon K., Freedman S. B., Wilcox I., Allman K., Madden A., Carter G. S., Harris P. J. The unstable ST segment early after thrombolysis for acute infarction and its usefulness as a marker of recurrent coronary occlusion. Am J Cardiol. 1991 Jan 15;67(2):109–115. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90430-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langer A., Krucoff M. W., Klootwijk P., Veldkamp R., Simoons M. L., Granger C., Califf R. M., Armstrong P. W. Noninvasive assessment of speed and stability of infarct-related artery reperfusion: results of the GUSTO ST segment monitoring study. Global Utilization of Streptokinase and Tissue Plasminogen Activator for Occluded Coronary Arteries. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Jun;25(7):1552–1557. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00110-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mauri F., Maggioni A. P., Franzosi M. G., de Vita C., Santoro E., Santoro L., Giannuzzi P., Tognoni G. A simple electrocardiographic predictor of the outcome of patients with acute myocardial infarction treated with a thrombolytic agent. A Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI-2)-Derived Analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Sep;24(3):600–607. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michels K. B., Yusuf S. Does PTCA in acute myocardial infarction affect mortality and reinfarction rates? A quantitative overview (meta-analysis) of the randomized clinical trials. Circulation. 1995 Jan 15;91(2):476–485. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.2.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mounsey J. P., Skinner J. S., Hawkins T., MacDermott A. F., Furniss S. S., Adams P. C., Kesteven P. J., Reid D. S. Rescue thrombolysis: alteplase as adjuvant treatment after streptokinase in acute myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1995 Oct;74(4):348–353. doi: 10.1136/hrt.74.4.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldroyd K. G., Pye M. P., Ray S. G., Christie J., Ford I., Cobbe S. M., Dargie H. J. Effects of early captopril administration on infarct expansion, left ventricular remodeling and exercise capacity after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 1991 Sep 15;68(8):713–718. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(91)90641-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ray S. G., Pye M., Oldroyd K. G., Christie J., Connelly D. T., Northridge D. B., Ford I., Morton J. J., Dargie H. J., Cobbe S. M. Early treatment with captopril after acute myocardial infarction. Br Heart J. 1993 Mar;69(3):215–222. doi: 10.1136/hrt.69.3.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saran R. K., Been M., Furniss S. S., Hawkins T., Reid D. S. Reduction in ST segment elevation after thrombolysis predicts either coronary reperfusion or preservation of left ventricular function. Br Heart J. 1990 Aug;64(2):113–117. doi: 10.1136/hrt.64.2.113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder R., Dissmann R., Brüggemann T., Wegscheider K., Linderer T., Tebbe U., Neuhaus K. L. Extent of early ST segment elevation resolution: a simple but strong predictor of outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994 Aug;24(2):384–391. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)90292-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schröder R., Wegscheider K., Schröder K., Dissmann R., Meyer-Sabellek W. Extent of early ST segment elevation resolution: a strong predictor of outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction and a sensitive measure to compare thrombolytic regimens. A substudy of the International Joint Efficacy Comparison of Thrombolytics (INJECT) trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Dec;26(7):1657–1664. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00372-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P. K., Cercek B., Lew A. S., Ganz W. Angiographic validation of bedside markers of reperfusion. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1993 Jan;21(1):55–61. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(93)90716-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starling M. R., Crawford M. H., Sorensen S. G., Levi B., Richards K. L., O'Rourke R. A. Comparative accuracy of apical biplane cross-sectional echocardiography and gated equilibrium radionuclide angiography for estimating left ventricular size and performance. Circulation. 1981 May;63(5):1075–1084. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.63.5.1075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmis G. C. ST segment analysis for determining the dynamic status of reperfusion therapy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Sep;26(3):684–687. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(95)00310-Z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zahger D., Cercek B., Cannon C. P., Jordan M., Davis V., Braunwald E., Shah P. K. How do smokers differ from nonsmokers in their response to thrombolysis? (the TIMI-4 trial) Am J Cardiol. 1995 Feb 1;75(4):232–236. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(95)80026-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]