Abstract

Objective—To describe the epidemiology and costs of coronary heart disease (CHD) requiring hospital admission, with particular reference to diabetes. Setting—The former South Glamorgan Health Authority, South Wales. Methods—Routine hospital activity data were record linked and all diabetic and non-diabetic individuals over a four year period (1991-95) were identified. A cost weight was included for each admission based on diagnosis related groups. Results—There were 10 214 patients admitted with a primary diagnostic code for CHD, representing an incidence of 6.3 per 1000 per annum. Including all CHD and non-CHD admissions, these individuals were responsible for 17% of acute inpatient activity. Men had a consistently higher age specific prevalence of CHD than women. The age adjusted relative risk of CHD for patients with diabetes compared with those without was 4.1 for men and 5.5 for women. Patients with diabetes accounted for 16.9% of CHD related admissions and had a fourfold increased probability of undergoing a cardiac procedure. The total cost of CHD was estimated to be 6% of NHS revenue at 1994-95 pay and prices. Patients with diabetes were responsible for 16% of this expenditure. This translated to an estimated NHS acute hospital expenditure for CHD of £1.1 billion per year at 1994-95 pay and prices. Conclusions—CHD was responsible for a larger proportion of NHS expenditure than had previously been reported. Nearly one in five acute hospital admissions were for patients whose condition included cardiac problems. The relation between diabetes and CHD was particularly evident, and may offer opportunities for disease prevention. Keywords: coronary heart disease; diabetes mellitus; cost and cost analysis; epidemiology

Full Text

The Full Text of this article is available as a PDF (120.9 KB).

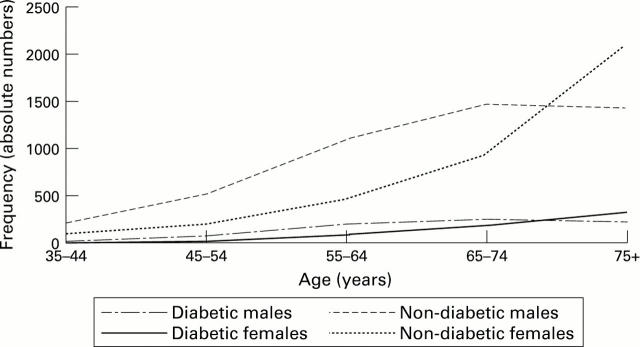

Figure 1 .

Frequency distribution of patients presenting with a primary diagnosis related to coronary heart disease over a four year period by age and sex.

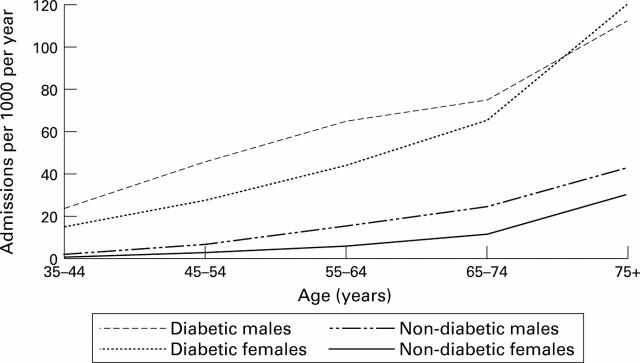

Figure 2 .

Incidence of coronary heart disease events requiring hospital admission in the diabetic and non-diabetic populations.

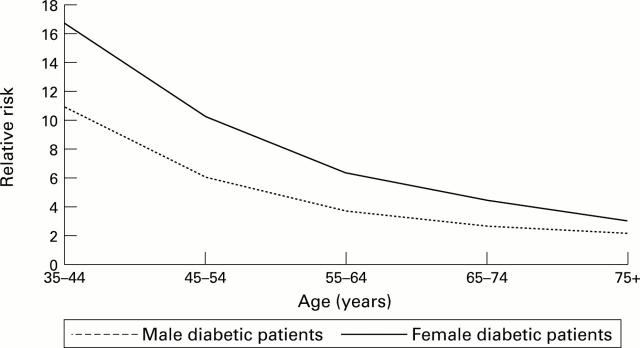

Figure 3 .

Relative risk of admission for coronary heart disease by age and sex: patients with and without diabetes.

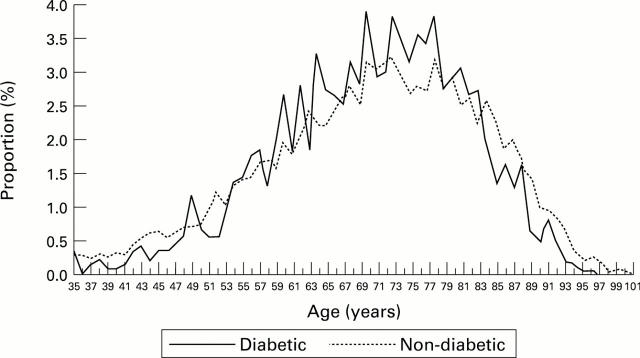

Figure 4 .

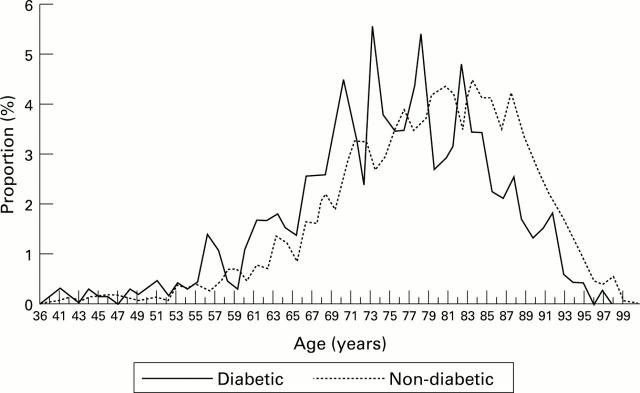

Age related to the proportions of all admissions for coronary heart disease: patients with and without diabetes.

Figure 5 .

Age at death related to the proportion of all coronary heart disease deaths: patients with and without diabetes.

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Barrett-Connor E. L., Cohn B. A., Wingard D. L., Edelstein S. L. Why is diabetes mellitus a stronger risk factor for fatal ischemic heart disease in women than in men? The Rancho Bernardo Study. JAMA. 1991 Feb 6;265(5):627–631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler C., Peters J., Stott N. Glycated haemoglobin and metabolic control of diabetes mellitus: external versus locally established clinical targets for primary care. BMJ. 1995 Mar 25;310(6982):784–788. doi: 10.1136/bmj.310.6982.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie C. J., Peters J. R. Sex and coronary heart disease: the relative probability of dying in hospital. Heart. 1997 Apr;77(4):371–372. doi: 10.1136/hrt.77.4.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie C. J., Williams D. R., Peters J. R. Patterns of in and out-patient activity for diabetes: a district survey. Diabet Med. 1996 Mar;13(3):273–280. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9136(199603)13:3<273::AID-DIA57>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill L., Goldacre M., Simmons H., Bettley G., Griffith M. Computerised linking of medical records: methodological guidelines. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1993 Aug;47(4):316–319. doi: 10.1136/jech.47.4.316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones S. L., Close C. F., Mattock M. B., Jarrett R. J., Keen H., Viberti G. C. Plasma lipid and coagulation factor concentrations in insulin dependent diabetics with microalbuminuria. BMJ. 1989 Feb 25;298(6672):487–490. doi: 10.1136/bmj.298.6672.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannel W. B. Lipids, diabetes, and coronary heart disease: insights from the Framingham Study. Am Heart J. 1985 Nov;110(5):1100–1107. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(85)90224-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krolewski A. S., Kosinski E. J., Warram J. H., Leland O. S., Busick E. J., Asmal A. C., Rand L. I., Christlieb A. R., Bradley R. F., Kahn C. R. Magnitude and determinants of coronary artery disease in juvenile-onset, insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Am J Cardiol. 1987 Apr 1;59(8):750–755. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(87)91086-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petticrew M., McKee M., Jones J. Coronary artery surgery: are women discriminated against? BMJ. 1993 May 1;306(6886):1164–1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.306.6886.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderlund N., Milne R., Gray A., Raftery J. Differences in hospital casemix, and the relationship between casemix and hospital costs. J Public Health Med. 1995 Mar;17(1):25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]