Abstract

Some findings suggest an infectious factor in cardiac myxoma and certain histopathological features indicate herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) infection. We hypothesized that HSV-1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of cardiac myxoma. Paraffin-embedded tissue samples from 17 patients with atrial myxoma were investigated for HSV-1 antigen by immunohistochemistry and viral genomic DNA by nested polymerase chain reaction. The histogenesis and oncogenesis of atrial myxoma were assessed by the expression of calretinin, Ki67, and p53 protein, respectively. Autopsy myocardial samples, including endocardium from 12 patients who died by accident or other conditions, were used for comparison. HSV-1 antigen was detected in atrial myxoma from 12 of 17 patients: 8 of these 12 samples were positive also for HSV-1 DNA. No HSV-1 antigen or DNA was found in tissue from the comparison group. Antigens of HSV-2, varicella-zoster virus, Epstein-Barr virus, and cytomegalovirus were not found in atrial myxoma. Calretinin was found in myxoma cells of all 17 cases but Ki67 was present only in smooth muscle cells or infiltrating cells in some cases. p53 was not detectable in any myxoma. Most infiltrating cells were cytotoxic T lymphocytes. These data suggest that HSV-1 infection is associated with some cases of sporadic atrial myxoma and that these may result from a chronic inflammatory lesion of endocardium.

Although benign, atrial myxoma is the most common primary cardiac tumor, with an incidence of about one per million population per year and a recurrence rate of 2% to 3%. 1,2 A total of 633 surgical cases of cardiac myxoma were reported in the Chinese medical literature from 1962 to 1988. 3 Cases usually present in the third to sixth decades of life and are more common in females. Diagnosis and treatment of atrial myxoma are established, but the underlying cause remains unknown. Atrial myxoma may induce one or more of the triad of embolism, intracardiac obstruction, and constitutional symptoms. The constitutional signs presented in about half of the patients include fatigue, fever, weight loss, and laboratory abnormalities such as elevation of leukocyte count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and serum C-reactive protein, suggesting an infectious disease. 4 Histological findings also support that atrial myxoma may arise via a reactive process rather than a neoplastic origin. 5,6

Herpes simplex virus type 1 is a neurotropic human pathogen capable of causing a variety of clinical diseases although the majority of infected immunocompetent patients are asymptomatic. The specific clinical illness will be determined by the portal of virus entry, the competence of the host immune system, and whether the infection is primary or recurrent. Following a primary infection, HSV-1 establishes a latent state in sensory or autonomic ganglia that is maintained for the life of the host. Periodically, the latent virus can be reactivated by a variety of endogenous and exogenous stimuli to cause asymptomatic viral shedding or symptomatic recurrent infections within the distribution of the affected nerve. 7 In experimental HSV-induced carditis in mice, HSV replication was found in the neurons and satellite cells of cardiac ganglia and endocardium, 8 supporting that HSV-1 can infect endocardium via the sensory nerves. Atrial myxoma originates in the endocardium, especially the atrial septum, which is rich with sensory nerves, and myxoma cells appear to be derived from endocardial sensory nerve tissue. 9 The mucosal vasculitis induced by HSV-1 is similar to the thick-walled dysplastic blood vessels in myxomas. 10 The fibrin deposition is found in both HSV-1 mucosal lesions and myxoma; also, the eosinophilic myxoma cells with three to nine nuclei are consistent with characteristic giant cells in herpesvirus-infected human tissue. 11 Importantly, myxoma cells synthesize highly sulfated glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans that are found to serve as a receptor for entry of HSV-1 to neuronal cells. 12,13 The above findings raise the possibility that HSV-1 infection may be involved in the pathogenesis of atrial myxoma. In the present study, we investigated whether HSV-1 infection is associated with atrial myxoma, using immunohistochemistry and nested polymerase chain reaction (nPCR) to detect viral antigens and DNA in tissue specimens, respectively. At the same time, we assessed the proliferative activity of myxoma cells and characterized the infiltrate in myxoma by immunohistochemistry.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Tumor samples resected from 17 patients with non-familial, atrial myxoma at Zhongshan Hospital, Fudan University, Shanghai, China were used in this retrospective study. Patients were aged from 15 to 70 years (mean, 44 years), and gender distribution was 5 male and 12 female. Constitutional symptoms were present in 9 cases. HSV-1-infected human embryo lung fibroblasts or tissue (DAKO Ltd, Cambridge, UK) were used as positive controls. Myocardial samples with endocardium taken at autopsy in China from 2 patients with amniotic embolism, 5 patients with enteroviral myocarditis, 3 patients with dilated cardiomyopathy, and 2 road traffic accidents. They were 4 male and 8 female individuals aged from 16 to 51 years (mean, 35), constituting the age- and sex-matched comparison group.

Histopathology and Immunohistochemistry

Myxoma samples were fixed in 10% neutral formalin and embedded in paraffin for histological examination. The presence of both myxoid stroma and myxoma cells in tissue sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) was diagnostic of atrial myxoma.

A monoclonal antibody (Mab) prepared using HSV-1 strain Stoker as antigen was supplied by Vector Lab Ltd (Newcastle, UK). This antibody does not cross-react with herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2), varicella-zoster virus (VZV), primary tissue culture isolates of cytomegalovirus (CMV), adenovirus, mumps virus, measles virus, or respiratory syncytial virus. Mabs directed against HSV-2, VZV, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), or calretinin were also from Vector Lab Ltd. MAbs against CD3, CD4, CD57, Ki67, p53, or actin of vessel smooth muscle cells were from NeoMarkers Inc. (Soham, Cambs., UK). An additional, polyclonal antiserum against HSV-1, Mabs against CD8, CD20, vascular endothelial cells (CD31) and CMV, N-Universal negative control reagents for mouse (cocktail of mouse IgG1, IgG2a, IgG 2b, IgG3 and IgM) or rabbit (immunoglobulin fraction from non-immunized rabbits), serum-free protein blocking buffer, antibody diluent and the EnVision detection system for mouse Mab or rabbit antiserum were purchased from DAKO Ltd (Cambridge, UK).

Antigen retrieval was achieved by heating dewaxed, rehydrated sections in citrate buffer or by trypsin digestion, before application of the primary antibody. Immunohistochemical staining was performed as described previously, 14 using antibodies in accordance with manufacturer’s recommendations. Positive control, comparison samples, and control reagents were included in each experiment.

DNA Extraction

Cell lysate (20 μl) of HSV-1- or mock-infected human embryo lung fibroblasts was incubated with 150 μl of digestion buffer (100 μg/ml proteinase K, 100 mmol/L NaCl, 10 mmol/L Tris-HCl, 25 mmol/L ethylene diaminetetraacetic acid and 0.5% sodium dodecyl sulfate) overnight at 55°C. Following phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation, the DNA pellet was dissolved in sterile distilled water and heated at 95°C for 15 minutes for PCR. Alternatively, five pooled 10-μm-thick sections of paraffin-embedded tissue were dewaxed with octane, rinsed with methanol, 15 dried under vacuum, and DNA isolated as from cultured cells.

DNA Amplification and Analysis

HSV-1 glycoprotein D (gD) is involved in both receptor-binding and cell fusion and has highly conserved but type-specific regions suitable for PCR primers. The sensitivity and specificity of the primers for HSV-1 amplification (Table 1) ▶ have been established previously. 16 These primers are widely used in research and diagnostic laboratories and were therefore chosen in this study. PCR amplification was carried out as described previously, 16 using Master Taq polymerase (Eppendorf Scientific Inc., Cambridge, UK). PCR products were characterized by agarose gel electrophoresis and direct nucleotide sequencing; sequence alignment and analysis were carried out as described previously. 17 β-globin gene sequences were amplified from each sample at the same time using GBN-F (forward) and GBN-R (reverse) primers (Table 1) ▶ . 15 Strict precautions were taken to avoid cross-contamination during PCR procedures.

Table 1.

Sequence and Location of Primers of HSV-1 and β-Globin

| Primers | Sequences (5′ to 3′) | Location | Size of product |

|---|---|---|---|

| HSV1.1 | ATCACGGTAGCCCGGCCGTGTGACA | 19----43 | 221 bp |

| HSV1.2 | CATACCGGAACGCACCACACAA | 239----218 | |

| HSV1.3 | CCATACCGACCACACCGACGA | 51----71 | 138 bp |

| HSV1.4 | GGTAGTTGGTCGTTCGCGCTGAA | 188----166 | |

| GBN-F | GAAGAGCCAAGGACAGGTAC | 793----812 | 268 bp |

| GBN-R | CAACTTCATCCACGTTCACC | 1060----1041 |

Results

Histopathological Findings

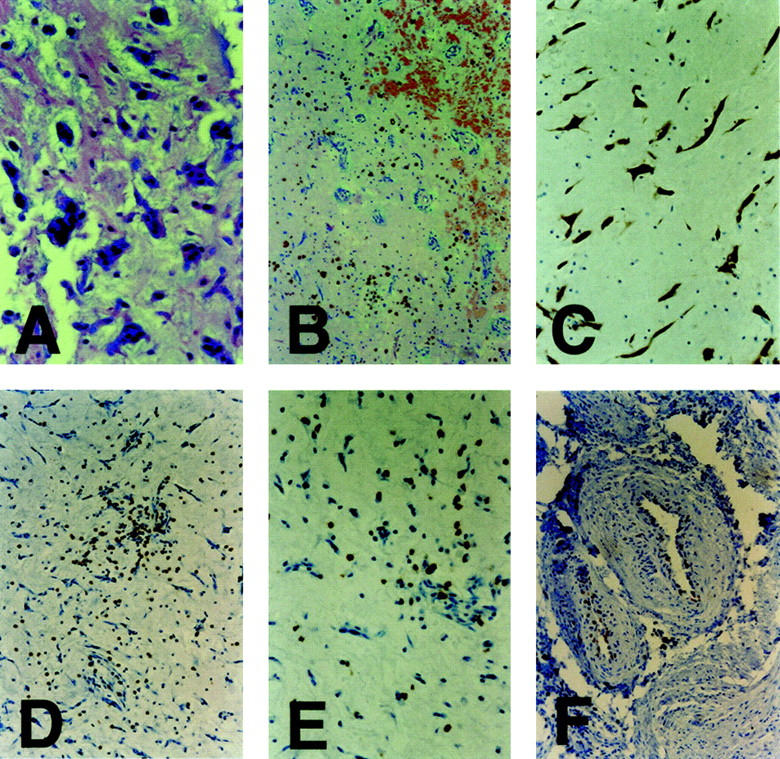

Atrial myxoma was localized to the left atrium in 15 cases and to the right in two. Scattered or clustered myxoma cells with scant eosinophilic cytoplasm were seen throughout the matrix in all cases. Multinucleate myxoma cells were seen in 14 cases (Figure 1A) ▶ and a glandular-like structure in one. Angiogenesis, confirmed by immunostaining specific for actin of vascular smooth muscle cells and endothelial cells, was seen in all cases and microscopic hemorrhage was present in 14 cases (Figure 1B) ▶ . No mitotic figure was seen in any case of atrial myxoma.

Figure 1.

Histopathology of atrial myxoma. A: H&E staining of a myxoma tissue section showing multinucleate myxomatous cells. B: H&E staining of a myxoma tissue section showing microscopic hemorrhage and angiogenesis. C: Immunohistochemical staining (brown deposits) for calretinin in myxomatous cells in an atrial myxoma tissue section. D: Immunohistochemical staining for numerous CD3-positive cells in a myxoma tissue section. E: Immunohistochemical staining for CD8-positive cells in a myxoma tissue section. F: Immunohistochemical staining for Ki67 expression in smooth muscle cells or possible endothelial cells. Original magnifications: A, C, D, and F, ×200; B, ×100; E, ×400.

Identification of Infiltrating Cells in Atrial Myxoma

Plasma cells, macrophages, lymphocytic infiltrates, and blood vessels were frequently seen in H&E-stained sections of atrial myxoma. Most of the scattered or clustered infiltrating cells were identified immunohistochemically as T lymphocytes (CD3+; Figure 1D ▶ ) including numerous cytotoxic T cells (CD8+; Figure 1E ▶ ) and fewer helper T lymphocytes (CD4+). Additionally, a few infiltrating B cells (CD20+) and natural killer cells (CD57+) were seen. The presence of plasma cells and T cells supports a humoral and cellular immune response in myxoma.

Expression of Calretinin, Ki67, and p53 in Atrial Myxoma

Calretinin is a 29-kd calcium-binding protein expressed in the central and peripheral nervous systems including sensory neurons, as well as in other normal or pathological mesothelial tissues, 18 and is a useful diagnostic marker of atrial myxoma. 19 In the present study, calretinin was expressed only in myxoma cells in all cases of atrial myxoma (Figure 1C) ▶ . Additionally, scattered staining for calretinin was seen in putative sensory nerve cells in myocardial tissues from the comparison group. These results support the diagnosis of myxoma and indicate a possible nervous origin of myxoma cells. 9,19

Ki67 is expressed in proliferating cells, but absent from resting cells. 20 Ki67 protein was detected in some vascular smooth muscle cells, infiltrating lymphoid cells or possible endothelial cells (Figure 1F) ▶ but not myxoma cells, in 11 of 17 myxoma cases. Ki67 protein was not present in any cell type in the remaining 6 cases. In agreement with the previous report, 21 no p53-specific staining was seen here in any case of atrial myxoma. Expression of the p53 tumor gene is enhanced during development of many human tumors.

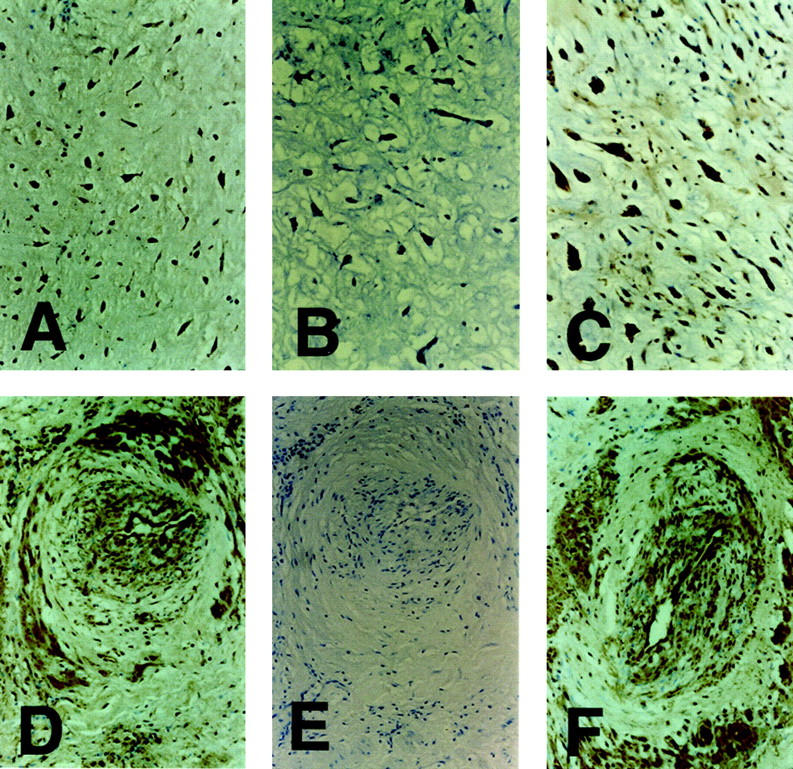

Detection of HSV-1 Antigen in Atrial Myxoma

Immunocytochemical staining with the Mab specific for HSV-1 antigen was located in the cytoplasm and nucleus of experimentally infected human embryo lung fibroblasts. Similar positive signals were seen in 12 cases of atrial myxoma, mainly in myxoma cells (Figure 2C) ▶ but also in endothelial and smooth muscle cells in some thick-walled blood vessels (Figure 2D) ▶ . The same distribution of HSV-1 antigen was seen after staining with the polyclonal antiserum (Figure 2, A and F) ▶ . When the primary antibodies were substituted with universal negative control reagents, no positive signal or non-specific staining of adjacent or consecutive tissue sections was seen (Figure 2, B and E) ▶ . Mock- or HSV-1-infected cultured cells or human lung tissue, stained with either the Mab or polyclonal antiserum for HSV-1 or with universal negative control reagents or dilution buffer only, gave the anticipated results. No HSV-1 antigen was detected in myocardial samples from 12 cases in the comparison group. The antigens of HSV-2, VZV, EBV, and CMV were also undetectable in any case of atrial myxoma, but were demonstrated in the viruses-infected cultured cells used as positive controls. These findings suggest the possibility that HSV-1, rather than other herpesviruses, may be associated with myxoma.

Figure 2.

Detection of HSV-1 antigens in atrial myxoma. Immunohistochemical staining of a myxoma tissue section, showing HSV-1 antigens in myxomatous cells (brown deposits), with the antiserum (A) or Mab (C). B: No signal of immunostaining of HSV-1 antigens was found with universal negative control reagents in an adjacent section. D: Immunostaining of HSV-1 antigens in endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in thick-walled vessels with the Mab (D) or antiserum (F). E: No signal of immunostaining of HSV-1 antigens was found with universal negative control reagents in a consecutive section. Original magnifications: A and B, ×100; C, D, E, and F, ×200.

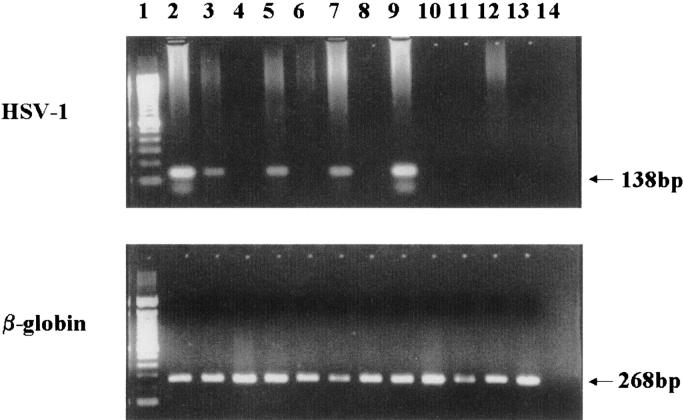

PCR Amplification of HSV-1 DNA from Atrial Myxoma

Amplified HSV-1 glycoprotein D gene sequences were not seen after electrophoresis of the first-round PCR product from tissue from any case of atrial myxoma, but further amplification using nested primers generated PCR product of predicted size in 8 cases (Figure 3) ▶ ; this suggests that viral DNA was present in low copy number although each was positive also for viral antigen. HSV-1 DNA was not found in any tissue sample from the comparison group. The β-globin gene sequence was amplified successfully from all samples from both groups (Figure 3) ▶ . The HSV-1 DNA sequence in myxoma was confirmed by nucleotide sequencing in both directions of representative amplified products, which matches the gD gene sequence of HSV-1 in the GenBank database (Accession No. E00401, data not shown).

Figure 3.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of PCR products. HSV-1 (top) and β-globin (bottom) PCR products from atrial myxoma tissue samples or from amniotic embolism were resolved in 2% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. Lane 1: 100 bp DNA ladder; lanes 2 to 11: atrial myxoma cases; lanes 12 and 13: amniotic embolism; lane 14: reagent control.

Discussion

This is the first study to show the presence of HSV-1 antigen and viral DNA, accompanied by inflammatory infiltration, hemorrhage, and angiogenesis, in some cases of sporadic atrial myxoma, and suggests that HSV-1 infection is associated with this disease. It is, however, not clear if HSV-1 infection results in the development of myxoma in some cases or the virus just infects these susceptible cells in myxomas. It is also unclear whether primary or recurrent HSV-1 infection is involved, as no markers of virus latency or reactivation were sought. Recently, CMV infection was found associated with a cardiac papillary fibroelastoma, 22 demonstrating that human herpesviruses can be present in cardiac tumors.

HSV-1 antigen was readily detectable in tissue sections from 12 of 17 atrial myxomas. However, virus DNA was detected in only 8 of these antigen-positive cases by the highly sensitive nested PCR. HSV-1 antigen was invariably present when virus DNA was detected. Discrepancies between detection rates of HSV-1 antigen and DNA were reported in previous investigations 23,24 but the reason for this in the present study is unclear. Sequences of the housekeeping gene β-globin were amplified successfully in each case, excluding the possibility of false negatives due to inhibitors such as hemoglobin or heparin. 25 Mutations in the viral target gene or the presence of empty or defected viral particles may contribute to the discrepancy. 26,27

It is known that HSV-1 infection can cause giant cell formation. Multinucleate myxoma cells were present in excised tissue from 14 of the 17 myxoma cases in this study. HSV-1 antigen was present mainly in myxoma cells, found previously to produce interleukin 6 (IL-6) 28 and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) 29 as do other HSV-1-infected cell types. High serum concentration of IL-6, thought to be responsible for the constitutional symptoms and immunological abnormalities in patients with atrial myxoma, 30 is also involved in HSV-1 reactivation from the neurons of sensory ganglia and protects mice from otherwise lethal HSV-1 infection. 31,32 In addition, HSV-1 infections can cause chronic synthesis of IL-6 within the nervous system. 33 VEGF is a major angiogenic factor responsible for vasculogenesis and remodeling: neovascularization of the cornea is found in experimental herpetic keratitis 34 and VEGF is secreted by spindle cells of the herpesvirus-related Kaposi’s sarcoma. 35 It is reported that VEGF is elevated in plasma from patients with atrial myxomas and plays a key role in angiogenesis, 36 a prominent feature of this tumor. Prolonged, excessive angiogenesis is a hallmark of inflammatory disorders in many organs.

Vascular changes associated with HSV infection in solid tissues, especially brain, include perivascular cuffing and hemorrhagic necrosis. Cuffing of thin-wall blood vessels by myxoma cells, giving rise to a double-walled appearance of vascular spaces, and microscopic hemorrhage, are almost universal findings in surgically resected myxomas. 10 HSV-1 antigen was also found in endothelial and vascular smooth muscle cells in some atrial myxomas in the present study, supporting the previous findings that HSV-1 can infect human vascular endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. HSV-1 infection of endothelium results in an increase in binding sites for inflammatory cells and shifts endothelial cell properties from anti- to pro-coagulant and anti- to prothrombotic, favoring thrombosis and hemorrhagic necrosis. 37,38 HSV infection can initiate or enhance smooth muscle cell proliferation 39 and coincidence of HSV-1 antigen and Ki67 protein in some smooth muscle cells suggests that HSV-1 infection may contribute to the formation of thick-walled vessels in atrial myxoma.

Persistent viral infection typically leads to chronic inflammation and cellular immunity, which is involved in preventing the transmission, spread, and end-organ pathology of HSV infection in humans. Both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells contribute to protection against lethal ocular HSV-1 infection in mice, but the present study showed that most infiltrating T cells in atrial myxoma were CD8+. It is established that CD8+ cells alone can prevent HSV-1 reactivation without lysis of infected neurons, 40 and a similarly restricted infiltrate is documented in herpesvirus-induced human encephalitis or myocarditis. 41,42

No mitosis was seen histologically in these atrial myxoma cases. Ki67 expression has been shown to correlate with tumor grade and prognosis in neoplastic cells 20 and increased p53 expression is common in human cancers. Neither was detected in myxoma cells in the present study, denying a role of malignancy in the genesis of atrial myxoma. These data, combined with the presence of HSV-1 antigens and DNA, angiogenesis, and an inflammatory response, support the concept that atrial myxoma results from a benign, reactive process 21 and may be a chronic inflammatory lesion of endocardium. Mitosis and Ki67 expression are absent in multinucleate myxoma cells, suggesting that these cells may be formed by cell fusion rather than cell proliferation. It is well established that the fusion of infected cells with neighboring cells in herpes lesions induced by several viral glycoproteins including gD, 43 producing polykaryocytes, is one of the pathways by which HSV-1 spreads in vivo.

The present study provides the direct evidence of the presence of HSV-1 in some cases of sporadic atrial myxoma and suggests these may result from a chronic inflammatory lesion of endocardium.

Footnotes

Address reprint requests to Dr. Hongyi Zhang, Health Protection Agency, Clinical Microbiology & Public Health Laboratory, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Level 6, Box 236, Hills Road, Cambridge CB2 2QW, UK. E-mail: hongyi.zhang@addenbrookes.nhs.uk.

Supported by grants from The Wellcome Trust, The British Heart Foundation, and the Carron Charitable Settlement.

References

- 1.MacGowan SW, Sidhu P, Aherne T: Atrial myxoma: national incidence, diagnosis and surgical management. Ire J Med Sci 1993, 162:223-226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhulaifi AM, Horner S, Pugsley WB, Sturridge MF: Recurrent left atrial myxoma. Cardiovasc Surg 1994, 2:232-236 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li GY: Incidence and clinical importance of cardiac tumors in China: review of the literature. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1990, 38(Suppl 2):205-207 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reynen K: Cardiac myxomas. N Engl J Med 1995, 333:1610-1617 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Salyer WR, Page DL, Hutchins GM: The development of cardiac myxomas and papillary endocardial lesions from mural thrombus. Am Heart J 1975, 89:4-17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nolan J, Carder PJ, Bloomfield P: Atrial myxoma: tumor or trauma? Br Heart J 1992, 67:406-408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitley R, Kimberlin D, Roizman: Herpes simplex viruses. Clin Infect Dis 1997, 26:541-555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grodums E, Zbitnew A: Experimental herpes simplex virus carditis in mice. Infect Immun 1976, 14:1322-1331 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Krikler DM, Rode J, Davies MJ: Atrial myxomas: a tumor in search of its origins. Br Heart J 1992, 67:89-91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deshpand A, Venugopal P, Kumar A, Chopra P: Phenotypic characterization of cellular components of cardiac myxoma: a light microscope and immunohistochemistry study. Hum Pathol 1996, 27:1056-1059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poste G: Virus-induced polykaryocytosis and the mechanism of cell fusion. Adv Virus Res 1970, 16:303-356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam RM, Hawkins ET, Roszka J: Cardiac myxoma: histochemical and ultrastructural localization of glycosaminoglycans and proteoglycans. Ultrastruct Pathol 1984, 6:69-81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shukla D, Spear P: Herpesviruses and heparan sulfate: an intimate relationship in aid of viral entry. J Clin Invest 2001, 108:503-510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang H, Li Y, Peng TQ, Aasa M, Zhang L, Yang Y, Archard LC: Localization of enteroviral antigen in myocardium and other tissues from heart muscle disease by an improved immunohistochemical technique. J Histochem Cytochem 2000, 48:579-584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fredricks DN, Relman DA: Paraffin removal from tissue sections for digestion and PCR analysis. BioTech 1999, 26:198-200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aurelius E, Johansson B, Skoldenberg B, Staland A, Forsgren M: Rapid diagnosis of herpes simplex encephalitis by nested polymerase chain reaction assay of cerebrospinal fluid. Lancet 1991, 337:189-192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li Y, Peng T, Yang Y, Niu C, Archard LC, Zhang H: High prevalence of enteroviral genomic sequences in myocardium from cases of endemic cardiomyopathy (Keshan Disease) in China. Heart 2000, 83:696-701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andressen C, Blumcke I, Celio MR: Calcium-binding proteins: selective markers of nerve cells. Cell Tissue Res 1993, 271:181-208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Terracciano LM, Mhawech P, Suess K, D’Armiento M, Lehmann FS, Jundt G, Moch H, Sauter G, Mihatsch MJ: Calretinin as a marker for cardiac myxoma: diagnostic and histogenetic considerations. Am J Clin Pathol 2000, 114:754-759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scholzen T, Gerdes J: The Ki-67 protein: from the known and the unknown. J Cell Physiol 2000, 182:311-322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Suvarna SK, Royds JA: The nature of the cardiac myxoma. Int J Cardiol 1996, 57:211-216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Grandmougin D, Fayad G, Moukassa D, Decoene C, Abolmaali K, Bodart JC, Limousin M, Warembourg H: Cardiac valve papillary fibroelastomas: clinical, histological and immunohistochemical studies and a physiopathogenic hypothesis. J Heart Valve Dis 2000, 9:832-841 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meijer A, Vliet A, Roholl P, Gielis-Proper S, Vries A, Ossewaarde J: Chlamydia pneumoniae in abdominal aortic aneurysm abundance of membrane components in the absence of heat shock protein 60 and DNA. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999, 19:2680-2686 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Raza-Ahmad A, Klassen GA, Murphy DA, Sullivan JA, Kinley CE, Landymore RW, Wood JR: Evidence of type 2 herpes simplex virus infection in human coronary arteries at the time of coronary artery bypass surgery. Can J Cardiol 1995, 11:1025-1029 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bezold G, Volkenandt M, Gottlober P, Peter RU: Detection of herpes simplex virus and varicella-zoster virus in clinical swabs: frequent inhibition of PCR as determined by internal controls. Mol Diagn 2000, 5:279-284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Coyle PV, Jain S, Wyatt D, McCaughey C, O’Neill HJ: Description of a nonlethal herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoprotein D deletion mutant affecting a site frequently used for PCR. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol 2000, 7:322-324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Openshaw H, McNeill J, Lin X, Niland J, Cantin E: Herpes simplex virus DNA in normal corneas: persistence without viral shedding from ganglia. J Med Virol 1995, 46:75-80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Acebo E, Val-Bernal J, Gomez-Roman J, Revuelta J: Clinicopathological study and DNA analysis of 37 cardiac myxoma: a 28-year experience. Chest 2003, 123:1379-1385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kono T, Koide N, Hama Y, Kitahara H, Nakano H, Suzuki J, Isobe M, Amano J: Expression of vascular endothellial growth factor and angiogenesis in cardiac myxoma: a study of fifteen patients. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2000, 119:101-107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mendoza CE, Rosado MF, Bernal L: The role of interleukin-6 in cases of cardiac myxoma: clinical features, immunologic abnormalities, and a possible role in recurrence. Texas Heart Inst J 2001, 28:3-7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomas J, Gangappa S, Chun S, Daheshia M, Rouse B: Herpes simplex replication induced expression of chemokines and proinflammatory cytokine in eye; implications in herpetic stromal keratitis. J Interferon Cytokine Res 1998, 18:681-690 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leblanc R, Pesnicak L, Cabral E, Godleski M, Straus S: Lack of interleukin-6 (IL-6) enhances susceptibility to infection but does not alter latency or reactivation of herpes simplex virus type 1 in IL-6 knockout mice. J Virol 1999, 73:8145-8151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker M, Noisakran S, Gebhardt B, Kriesel J, Carr D: The relationship between interlukin-6 and herpes simplex virus type 1: implications for behavior and immunopathology. Brain Behav Immun 1999, 13:201-211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Metcalf JF, Reichert RW: Histological and electron microscopic studies of experimental herpetic keratitis in the rabbit. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 1979, 18:1123-1138 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boshoff C: Kaposi’s sarcoma: coupling herpesvirus to angiogenesis. Nature 1998, 391:24-25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bennett KR, Gu JW, Adair TH, Heath BJ: Elevated plasma concentration of vascular endothelial growth factor in cardiac myxoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2001, 122:193-194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Visser MR, Tracy PB, Vercellotti GM, Goodman JL, White JG, Jacob HS: Enhanced thrombin generation and platelet binding on herpes simplex virus-infected endothelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1988, 85:8227-8230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Key NS, Vercellotti GM, Winkelmann JC, Moldow CF, Goodman JL, Esmon NL, Esmon CT, Jacob HS: Infection of vascular endothelial cells with herpes simplex virus enhanced tissue factor activity and reduced thrombomodulin expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1990, 87:7095-7099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yamashiroya HM, Ghosh L, Yang R, Robertson AL: Herpesviridae in the coronary arteries and aorta of young trauma victims. Am J Pathol 1988, 130:71-79 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu T, Khanna KM, Chen XP, Fink DJ, Henddricks RL: CD8+ cells can block herpes simplex virus type 1 (HSV-1) reactivation from latency in sensory neurons. J Exp Med 2000, 191:1459-1466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lellouch-Tubiana A, Fohlen M, Robain O, Rozenberg F: Immunocytochemical characterization of long-term persistent immune activation in human brain after herpes simplex encephalitis. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2000, 26:285-294 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koga M, Fujiwara M, Ariga S, Isumi H, Tashiro N, Matsubara T, Furukawa S: CD8+ T-lymphocytes infiltrate the myocardium in fulminant herpes virus myocarditis. Pediatr Pathol Mol Med 2001, 20:189-195 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Browne H, Bruun B, Whiteley A, Minson T: Plasma membrane requirements for cell fusion induced by herpes simplex virus type 1 glycoproteins gB, gD, gH and gL. J Gen Virol 2001, 82:1419-1442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]