Abstract

Species of Phaeoacremonium (especially Phaeoacremonium aleophilum) are associated with two severe diseases in grapevines, Petri disease in young plants and Esca disease in adult plants. Phaeoacremonium species grow slowly on culture medium, and it is difficult to identify these species on the basis of morphological characteristics. Primers Pm1 and Pm2 were designed in the ribosomal DNA internal transcribed spacer (ITS) regions ITS1 and ITS2, respectively. They yielded a single amplicon of 415 bp for nine species of Phaeoacremonium that may occur in grapevines. A nested PCR (using general fungal primers ITS1F/ITS4 in the primary reaction) was developed to detect Phaeoacremonium directly in grapevine wood. Molecular detection was more sensitive than the traditional method of culturing in growth medium was. Identification of Phaeoacremonium species was achieved by digesting the PCR-amplified fragment with the restriction enzymes BssKI, EcoO109I, and HhaI. It was possible to distinguish these species by their restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns, except for Phaeoacremonium viticola and Phaeoacremonium angustius, which had 100% similarity in their ITS region sequences. A species-specific PCR amplification of the partial β-tubulin gene using the primer pair Pbr4_1/T1 and Pbr8/T1 was necessary to differentiate P. angustius from P. viticola, respectively. An easy and fast protocol was developed to detect and identify species of Phaeoacremonium in a few hours. Primers defined here can be used in a plant nursery sanitation program to produce plants free of Phaeoacremonium spp. Use of healthy grapevine plants in new plantations is the most effective measure to manage Petri disease.

The hyphomycete genus Phaeoacremonium W. Gams, Crous & M. J. Wingfield is an ecologically important taxon that includes species associated with declining disease of woody plants and infections in humans (3, 8, 18, 25). In grapevine (Vitis vinifera L.), the two most serious destructive declining diseases are Petri disease in young plants and Esca disease in adult vines. The main pathogens identified in Petri disease are Phaeoacremonium spp. (most frequently Phaeoacremonium aleophilum) and Phaeomoniella chlamydospora (formerly known as Phaeoacremonium chlamydosporum) which are associated with the internal wood symptoms of dark brown to black streaking in a longitudinal section of stems. The importance of Petri disease has been emphasized, since it has been suggested these fungi act as pioneer organisms in the later invasion of the wood decay fungi that cause the typical symptoms of Esca disease inside the trunk and branches (23).

The genus Phaeoacremonium was described in 1996 (3) and included some plant- and human-infecting isolates grouped with the name of Phialophora parasitica. Six new species, including the type species Phaeoacremonium parasiticum, were described then (3). The other Phaeoacremonium species were P. aleophilum, P. angustius, and P. chlamydosporum isolated from grapevines and P. inflatipes and P. rubrigenum isolated from humans and plants (including vines). In later studies, P. chlamydosporum appeared unrelated phylogenetically to other species of the genus (7), and it was renamed Phaeomoniella chlamydospora (4). Two new Phaeoacremonium species were later described: P. mortoniae (17) and P. viticola (8). Subsequent DNA phylogenetic study of the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) region, ITS1/5.8S gene/ITS2, and especially of the β-tubulin, actin, and calmodulin gene regions of the Phaeoacremonium species brought the description of an important number of novel species or the reassignment of former ones. Thus, the Phaeoacremonium genus grew to include five new species, P. australiense, P. krajdenii, P. scolyti, P. subulatum, and P. venezuelense, that grow on grapevines (24); P. rubrigenum was shown to occur only on humans (24). Recently, two other new Phaeoacremonium species on grapevines were defined, P. austroafricanum and P. iranianum (25). This makes a total of 13 Phaeoacremonium species that are reported to grow on grapevines.

Identification of species of Phaeoacremonium is not easy. It is done by traditional methods of isolation and culturing and subsequent description of morphological characteristics. There are some morphological identification keys (3, 8, 24), but distinguishing between the characteristics has proven to be difficult and it has resulted in some misidentifications. Moreover, Phaeoacremonium spp. are slow-growing fungi which usually take up to 20 days to grow on enriched medium. Phaeoacremonium is frequently overgrown by other microorganisms; then subculturing is required, which makes the identification process longer. Molecular tools have contributed to identify Phaeoacremonium species. Restriction patterns of the ITS ribosomal DNA (rDNA) and a partial fragment of the β-tubulin gene were used to distinguish Phaeoacremonium parasiticum from Phaeoacremonium inflatipes (9) and to identify some of the Phaeoacremonium species associated with diseased grapevines (9, 33). Species-specific primers based on ITS region of rDNA have been widely used to detect and identify Phaeoacremonium aleophilum and Phaeomoniella chlamydospora from a worldwide range of sources (5, 16, 28, 30, 33, 36). A set of species-specific primers targeting the β-tubulin and actin gene have been designed for each of the 22 species in the Phaeoacremonium taxon (25). These primers can be combined in a multiplex PCR to identify simultaneously at most two species of Phaeoacremonium.

Management of young grapevine declining disease or Petri disease relies on the use of pathogen-free plants for new plantings (32). Infection may take place in plant nurseries during the propagation process and storage (29, 37). It may also happen because of the use of infected mother plants (10, 12). Rootstock material used for propagation has been reported to harbor trunk disease pathogens and especially Phaeoacremonium species (1, 11, 13, 15, 30). Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium spp. have been detected in both symptomatic and asymptomatic cuttings (2).

The aims of this work were, first, to design Phaeoacremonium-specific primers for the detection of any species of Phaeoacremonium infecting grapevine and, second, to develop an accurate restriction pattern of the resulting amplicon for the identification of the Phaeoacremonium species.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolates of Phaeoacremonium.

A total number of 56 Phaeoacremonium isolates were used in this study (Table 1). Thirty-nine isolates were isolated in 2003, 2004, and 2005 from diseased grapevines collected in different locations or rootstocks from plant nurseries in Spain. Seven ex-type cultures obtained from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures (CBS) (Table 1) were used to optimize conditions for amplifying a Phaeoacremonium-specific DNA fragment. Nine ex-type strains (including the first seven species and three new defined species and discarding P. rubrigenum because it was not longer reported to occur on grapevines) (Table 1) were used for verifying the restriction digestion pattern of the amplicon. Other CBS cultures and field isolates were used to evaluate the method presented here (Table 1). Each isolate was plated on 2% malt extract agar (MEA) (Conda Laboratories, Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain) and incubated at 25°C in the dark in order to obtain mycelium for DNA extraction. All isolates were stored at 4°C in sterile water.

TABLE 1.

Phaeoacremonium isolates used in this study

| Phaeoacremonium species | No. of isolates | GenBank accession no.a | Origin | Yr of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. parasiticum | U31841 | CBS860.73b,c,d | 1973 | |

| CBS113591e | ||||

| 2 (1)f | Plant nursery in Murcia, Spain | 2004 | ||

| 2 (1) | Plant nursery in Cataluña, Spain | 2005 | ||

| 1 (1) | Cataluña, Spain | 2005 | ||

| P. rubrigenum | AF118139 | CBS498.94c | 1994 | |

| P. inflatipes | AF197990 | CBS391.71c,d | 1966 | |

| CBS166.75e | 1974 | |||

| P. mortoniae | AF295328 | CBS211.97e | ||

| CBS101585c,d | 1998 | |||

| P. viticola | AF118137 | CBS113065e | 2001 | |

| CBS101738c,d | 1993 | |||

| 1 (1) | Cataluña, Spain | 2005 | ||

| P. angustius | AF197974g | |||

| CBS114992c,d | 1992 | |||

| CBS114991e | ||||

| P. krajdenii | CBS109479d | 2001 | ||

| P. venezuelense | CBS651.85d | 1974 | ||

| P. scolyti | CBS113593d | |||

| CBS113597e | 1999 | |||

| P. aleophilum | AF017651 | CBS246.91c,d | 1996 | |

| CBS110753e | 1998 | |||

| 1 | Toscana, Italy | |||

| 16 (1) | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2003 | ||

| 2 (2) | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2004 | ||

| 4 | Cataluña, Spain | 2005 | ||

| 2 | Plant nursery in Portugal | 2004 | ||

| 5 (1) | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 | ||

| 1 | Plant nursery in Murcia, Spain | 2004 | ||

| 2 | Plant nursery in Cataluña, Spain | 2005 |

GenBank accession numbers of the ITS sequences used to design the primers and the discriminant restriction enzyme digestion patterns.

CBS isolates are from the Centraalbureau voor Schimmelcultures, Baarn, The Netherlands.

Ex-type strains used to optimize PCR conditions.

Ex-type strains used to test PCR-RFLPs.

CBS isolates used to validate the identification by PCR-RFLP.

The numbers in parentheses are the numbers of field isolates identified by ITS sequences (and β-tubulin for P. viticola) used to validate the identification by PCR-RFLP.

ITS sequence of CBS isolate 249.95. This was the original holotype of P. angustius, which was replaced with CBS114992 when lethally contaminated.

Other fungal isolates.

Other fungal isolates collected from grapevines (Table 2) were tested to verify that PCR primers were specific for the amplification of Phaeoacremonium DNA. They were obtained from the same surveys as Phaeoacremonium isolates were. These isolates were previously identified (1) on the basis of their morphology (3, 4, 6, 8, 27, 35) or their identification by a BLAST search in the GenBank database using the ITS region.

TABLE 2.

Fungal isolates used in this study to verify the specificity of PCR primers

| Fungal species | No. of isolates | Origin | Year of isolation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phaeomoniella chlamydospora | 1 | Toscana, Italy | |

| 2 | Madrid, Spain | 2003 | |

| 1 | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2003 | |

| Eutypa lata | 1 | Cataluña, Spain | 2002 |

| Acremonium alternata | 2 | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2004 |

| 2 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 | |

| 1 | Plant nursery in France | 2004 | |

| Acremonium strictum | 1 | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2004 |

| Phialophora spp. | 1 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 |

| Botryosphaeria obtusa | 1 | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2004 |

| 1 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 | |

| Botryosphaeria parva | 1 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 |

| Sporotrix spp. | 1 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 |

| Phomopsis quercella | 2 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 |

| Cylindrocarpon spp. | 3 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 |

| 1 | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2004 | |

| Phomopsis spp. | 1 | Ciudad Real, Spain | 2004 |

| Phomopsis viticola | 1 | Plant nursery in Huesca, Spain | 2004 |

| Phomopsis spp. | 1 | Plant nursery in Valencia, Spain | 2004 |

| Phialophora mustea | 1 | Cataluña, Spain | 2005 |

| Phialemonium dimorphosporum | 1 | Cataluña, Spain | 2005 |

| Fomitiporia punctata | 1 | Cataluña, Spain | 2005 |

DNA extraction.

Fungal DNA was extracted from either fresh mycelium ground with liquid N2 or freeze-dried mycelium, using the commercially available DNeasy plant mini kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). DNA samples were kept at −20°C until they were used for PCR amplifications.

Primer design.

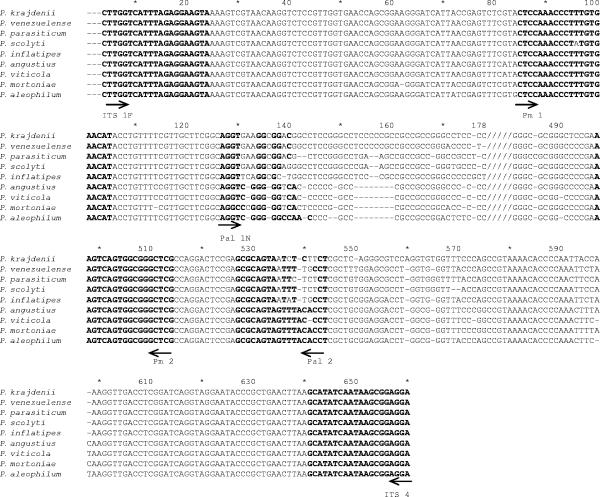

ITS sequences of seven holotype species of Phaeoacremonium were used to design a genus-specific primer pair (Table 1). ITS sequences were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) (Bethesda, MD). Nucleotide sequences were aligned using ClustalX version 1.81 (34) and then checked visually and adjusted manually if necessary. On the basis of these sequences, three putative primers were designed to amplify the ITS1 and ITS2 regions of rDNA (see Fig. 4). The primers were Pm1 (5′-CTC CAA ACC CTT TGT GAA CAT-3′) (forward primer), Pm2 (5′-CGA GCC CGC CAC TGA CTT-3′) (reverse primer), and Pm3 (5′-GCG AGC CCG CCA CTG ACT TT-3′) (reverse primer). The primers had no homology with other sequences as shown by a search done with the BLASTN program on the NCBI homepage (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/). The Net Primer program (http://www.premierbiosoft.com/netprimer) was used to check the viability of these primers. Primers were synthesized by Sigma-Aldrich (Haverhill, Suffolk, United Kingdom).

FIG. 4.

rDNA sequence alignment of the ITS1/5.8S/ITS2 regions from species of Phaeoacremonium listed in Table 1. Dashes represent gaps, bold characters indicate the annealing sites for each primer, and slashes indicate that sequences from positions 178 to 480 are not provided because they are not necessary to illustrate alignment of sequences and primers. The sense of each primer is in accordance with the direction of the arrow shown below the sequences.

PCR amplifications.

PCR conditions were optimized using DNA from the seven Phaeoacremonium ex-type cultures for which primers were designed (Table 1). Then, the specificity of genus-specific primers was confirmed using DNA from all isolates listed in Tables 1 and 2. PCRs were carried out in a final volume of 25 μl, and the reaction mixtures contained 2 μl of 10× buffer [75 mM Tris HCl, pH 9.0, 50 mM KCl, 20 mM (NH4)2SO4] (Biotools, Madrid, Spain), 0.2 μM (each) primer (Sigma-Aldrich, Haverhill, Suffolk, United Kingdom), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM deoxynucleoside triphosphates (dNTPs), 1 U Taq polymerase (Biotools), and 10 ng of DNA template for each reaction. To achieve maximum efficiency in the amplification, 2.5 μl of bovine serum albumin (BSA) (10 mg/ml; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) and 10% of dimethyl sulfoxide (Amresco, OH) were added. DNA amplifications were carried out in a Perkin-Elmer 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) by the following program: (i) an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 5 min; (ii) 40 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of denaturation (30 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s at 52°C), and extension (50 s at 72°C); and (iii) a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. The viability of DNA samples was checked with universal primers ITS1F and ITS4 at 53°C as the annealing temperature. Amplified fragments were visualized under UV light after electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels stained with ethidium bromide and run in 1× TBE buffer (Tris-borate-EDTA). A positive control (Phaeoacremonium ex-type DNA) and a negative control (no DNA) were included in each test.

Detection of Phaeoacremonium spp. in grapevine wood.

A nested PCR was performed to achieve more sensitivity detecting Phaeoacremonium directly from wood. PCR conditions were optimized using DNA from the seven Phaeoacremonium ex-type cultures (Table 1), and then they were checked for specific amplification using the isolates listed in Table 2. A primary PCR was done using the universal primers ITS1F/ITS4 (14); it was performed in a volume of 25 μl containing 2 μl of 10× buffer, 0.2 μM (each) primer, 2 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs, 0.75 U of Taq polymerase, 2.5 μl of BSA, and 1 μl of DNA as template (approximately 10 ng of DNA). Conditions consisted of an initial denaturation step at 94°C for 2.5 min; 35 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of 15 s at 94°C, 30 s at 53°C, and 90 s at 72°C; and a final extension step at 72°C for 7 min. PCR product was diluted 1:200, and then, 1 μl was used as DNA template for the secondary PCR using primer pair Pm1/Pm2. The concentrations of the reagents in a final volume of 25 μl were as follows: 2.5 μl of 10× buffer, 0.5 μM (each) primer, 4 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM dNTPs, and 1.25 U Taq polymerase. Thermal conditions were 5 min at 94°C, followed by 30 cycles (1 cycle consisting of 30 s at 94°C, 30 s at 57°C, and 50 s at 72°C), with a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. DNA extracted from in vitro grapevine plants was included in all reactions as a negative control.

PCR detection of Phaeoacremonium spp. in wood was checked in nine grapevine plants sampled from a plant nursery. The sensitivity of PCR was compared to the sensitivity of the traditional method of culturing in a rich medium. Fragments of 3 to 4 cm long were taken from each plant (six or seven fragments from rootstock and one from each graft union and scion), and the bark was removed. Six wood sections (1 to 2 mm thick) were obtained from each fragment, and three fragments were used in each method. When disks were used to detect Phaeaoacremonium by isolation in a growth medium, they were immersed in 70% ethanol for 1 min, air dried under sterile conditions, and plated on streptomycin-amended MEA (Conda Laboratories, Torrejón de Ardoz, Madrid, Spain) (three disks per plate). Petri dishes were incubated for 15 to 20 days at 25°C. Disks used for nested PCR were ground in liquid nitrogen, and DNA was extracted using the DNeasy plant mini kit. DNA samples were kept at −20°C until they were used for PCR amplifications.

Restriction enzyme digestion.

Restriction maps of the ITS sequences were defined using the Mapdraw program from the Lasergene package (version 3.13; DNAstar, Madison, WI) for the holotype strains of nine Phaeoacremonium species. Three enzymes, BssKI, EcoO109I, and HhaI, that generated discriminant profiles among the species were selected. Conditions for enzyme digestion were as follows: (i) for BssKI, 3 units of enzyme (New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA), 2 μl of PCR product, 2 μl of the buffer enzyme, and 2 μl of BSA, digested for 1 hour at 60°C in a final volume of 20 μl; (ii) for EcoO109I, 1 unit of enzyme (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan), 3 μl of PCR product, and 4 μl of the buffer enzyme, digested for 1 hour and 30 min at 37°C in a final volume of 40 μl; and (iii) for HhaI, 8 units of enzyme (Takara Bio Inc., Otsu, Shiga, Japan), 2 μl of PCR product, and 3 μl of the buffer enzyme, digested for 1 hour and 30 min at 37°C in a final volume of 30 μl. Restriction fragments were separated on 2.5% Metaphor agarose (Cambrex) using TBE buffer in the electrophoresis. An undigested PCR product was used as a control for nondigestion, and 100-bp (Biotools, Madrid, Spain) and 20-bp (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) molecular size markers were used to compare the size of each band. The digestion profile was visualized under UV light after staining with ethidium bromide.

Confirmation of PCR-RFLP method.

To confirm that enzyme digestion patterns clearly differentiate species of Phaeoacremonium, the PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) method was validated using CBS strains and several field isolates (Table 1). The species identifications of these field isolates were double checked by sequencing the ITS region amplified with universal primers ITS1F and ITS4 and by a subsequent BLAST search of the GenBank database (NCBI, Bethesda, MD).

β-Tubulin PCR.

To distinguish Phaeoacremonium angustius from Phaeoacremonium viticola, PCR amplification using primers targeting the β-tubulin gene was done. Reverse primers Pbr4_1 and Pbr8 (25) were used to amplify P. angustius and P. viticola, respectively, in combination with universal forward primer T1 (26). PCR conditions were optimized using DNA from ex-type strains P. angustius (CBS114992) and P. viticola (CBS101738). PCR amplification was performed in a Perkin-Elmer 9700 thermal cycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as follows: (i) an initial denaturation step of 5 min at 94°C; (ii) five cycles, with one cycle consisting of denaturation (30 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s at 57°C), and extension (60 s at 72°C); (iii) five cycles, with one cycle consisting of denaturation (30 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s at 56°C), and extension (60 s at 72°C); and (iv) 25 cycles, with 1 cycle consisting of denaturation (30 s at 94°C), annealing (30 s at 55°C), and extension (60 s at 72°C); (v) a final extension step of 7 min at 72°C. PCR mix contained 10 ng of DNA template, 2.5 μl 10× buffer, 0.5 μM (each) primer (MWG-Biotech, Germany), 4 mM MgCl2, 0.8 mM dNTPs, and 1.25 U Taq polymerase (Biotools, Madrid, Spain) in a final volume of 25 μl. These PCR conditions were tested using DNA from nine different species of Phaeoacremonium (Table 1) to confirm their specificity.

RESULTS

PCR detection of Phaeoacremonium spp. from mycelium.

Amplifications performed with PCR primers Pm1 and Pm2 yielded a fragment of the expected size (415 bp) for all seven ex-type strains of the Phaeoacremonium genus (Fig. 1). Furthermore, primer pair Pm1 and Pm2 detected more species than the seven Phaeoacremonium spp. for which the primers were initially designed (P. aleophilum, P. parasiticum, P. rubrigenum, P. inflatipes, P. mortoniae, P. angustius, and P. viticola). During the course of this work, new Phaeoacremonium species were defined, and DNA from some new Phaeoacremonium species tested (P. krajdenii, P. venezuelense, and P. scolyti) was successfully amplified using primers Pm1 and Pm2 (Fig. 1). Primer pair Pm1 and Pm3 yielded no PCR amplification for every Phaeoacremonium species tested, so they were not used to detect Phaeoacremonium species.

FIG. 1.

PCR amplifications using primers Pm1 and Pm2 on DNA extracts from Phaeoacremonium (lanes 1 to 9) and other fungal species (lanes 10 to 15). Lanes: M, molecular size markers (100 bp); 1, P. aleophilum (CBS 246.91); 2, P. parasiticum (CBS860.73); 3, P. inflatipes (CBS391.71); 4, P. mortoniae (CBS101585); 5, P. angustius (CBS114992); 6, P. viticola (CBS101738); 7, P. scolyti (CBS113597); 8, P. krajdenii (CBS 109479); 9, P. venezuelense (CBS651.85); 10, Botryosphaeria parva; 11, Phomopsis spp.; 12, Phaeomoniella chlamydospora; 13, Botryosphaeria obusa; 14, Phialophora mustea; 15, Phialemonium dimorphosporum; 16, grapevine DNA; 17, no DNA.

Designed primers Pm1 and Pm2 were evaluated using DNA from 49 Phaeoacremonium isolates (39 field isolates and 10 from CBS) (Table 1). An amplicon of approximately 415 bp was always obtained. In contrast, no amplification was obtained with DNA extracted from 28 isolates coming from different species isolated from grapevines (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Detection of Phaeoacremonium spp. in grapevine wood.

PCR amplifications using general fungal ITS primers were always successful and required a 200 times dilution of the PCR product to prevent inhibition in the secondary PCR. The final PCR product size was about 415 bp, as obtained in the simple PCR. Likewise, nested PCR specifically amplified Phaeoacremonium spp. but not any other fungal species listed in Table 2. DNA from in vitro grapevine plants was never amplified using primers ITS1F/ITS4.

Previous ground wood in liquid nitrogen allowed proper DNA extraction with the DNeasy plant mini kit. DNA extracted by this method was always visible on 0.8% agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide. The estimated DNA yield was about 100 ng/μl.

Nine plants were checked for the presence of Phaeoacremonium spp., and results were compared to those obtained incubating thin disks on MEA. The molecular method detected the pathogen in eight plants, whereas the traditional method of isolation detected it in five plants. The overall number of fragments per plant in which Phaeoacremonium was detected was higher by nested PCR (Table 3), so a lower number of fragments was required to detect an infected plant. When detection was performed by the traditional method of growing the fungus in a rich medium, the pathogen was found more frequently in the fragment below the graft union.

TABLE 3.

Comparison of nested PCR and culturing methods to detect Phaeoacremonium spp. in fragments from naturally infected grapevine plants

| No. of fragments/plant | No. of fragments with positive resulta by:

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Nested PCR | Culture in MEA | |

| 8 | 7 | 2 |

| 9 | 9 | 4 |

| 8 | 8 | 1 |

| 8 | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 6 | 2 |

| 8 | 5 | 1 |

| 8 | 4 | 0 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 |

| 8 | 3 | 0 |

Number of fragments in which Phaeoacremonium spp. were detected.

Identification of Phaeoacremonium species by PCR-RFLP.

The three selected enzymes, BssKI, EcoO109I, and HhaI, digested PCR products successfully. Phaeoacremonium species were identified by the observed band profiles, although expected bands smaller than 40 bp were visualized with difficulty on a stained gel. Reaction conditions for each digestion were optimized using PCR amplicon DNA from nine Phaeoacremonium ex-types; once they were established, CBS strains and field Phaeoacremonium isolates previously classified by ITS sequences (Table 1) were used to confirm the results of this identification method. Finally, other Phaeoacremonium isolates (Table 1) were identified following the strategy explained below.

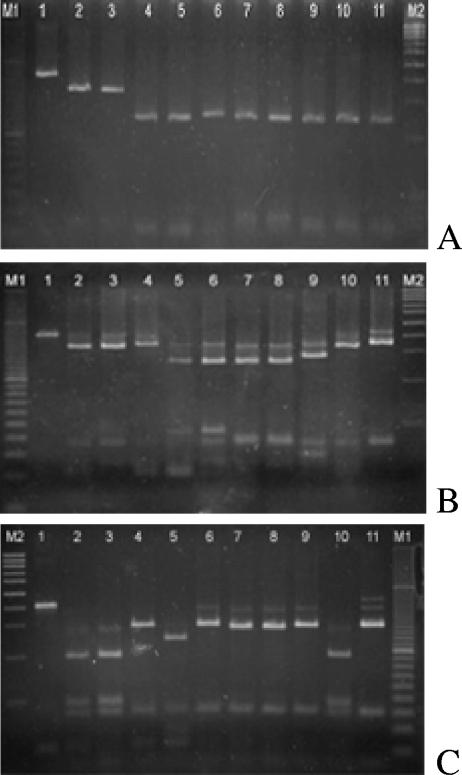

The first digestion was achieved with BssKI enzyme to distinguish Phaeoacremonium aleophilum from other Phaeoacremonium species. The BssKI-digested Phaeoacremonium amplicon showed a band of 338 bp for P. aleophilum and a band of 250 bp for other species (Fig. 2). This difference was sufficient to identify P. aleophilum. A second digestion was performed with EcoO109I to identify P. parasiticum and P. scolyti. The patterns were two bands of 344 bp and 49 bp for P. parasiticum and two bands of 288 bp and 56 bp for P. scolyti. These profiles were easily visualized in the stained gel (Fig. 2). The other species exhibited three different profiles: one that included P. mortoniae and P. krajdenii with bands of 340 bp and 72 bp; another group that included P. venezuelense and P. inflatipes with bands of 263 bp and 85 bp; and a last one with P. angustius and P. viticola with bands of 262 bp and 71 bp. To sort out these species, a third digestion with HhaI enzyme was done. P. venezuelense was distinguished by a band of 296 bp, and P. inflatipes was distinguished by a 241-bp band. P. mortoniae showed a band of 192 bp, while P. krajdenii had a band of 297 bp. P. angustius and P. viticola were not distinguishable by digestion of the amplicon with any restriction enzyme, so it was necessary to use specific primers based on the β-tubulin gene to identify these species.

FIG. 2.

Restriction fragment length polymorphism patterns of PCR-amplified Phaeoacremonium DNA using primers Pm1 and Pm2 digested with BssKI (A) Eco109I (B), and HhaI (C). Lanes: 1, undigested Phaeoacremonium; 2, P. aleophilum (CBS246.91); 3, P. aleophilum (CBS110753); 4, P. parasiticum (CBS860.73); 5, P. inflatipes (CBS391.71); 6, P. venezuelense (CBS651.85); 7, P. viticola (CBS101738); 8, P. angustius (CBS114992); 9, P. scolyti (CBS113597); 10, P. mortoniae (CBS101585); 11, P. krajdenii (CBS 109479); M1 and M2, molecular size markers of 100 bp and 20 bp, respectively.

β-Tubulin PCR.

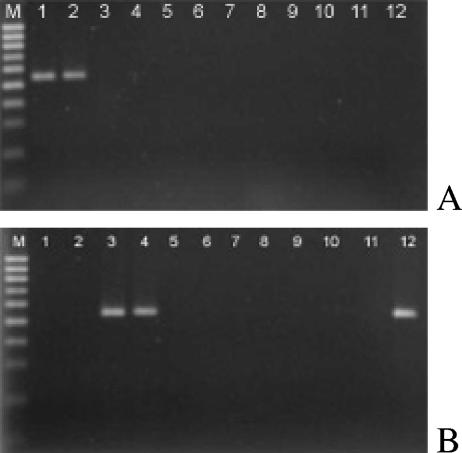

PCR conditions were optimized for ex-type strains of Phaeoacremonium angustius and Phaeoacremonium viticola using primers targeting the β-tubulin gene (Pbr4_1/T1 and Pbr8/T1). Then, 16 CBS isolates (Table 1) were used to verify the specificity of these primers. Amplification of P. angustius DNA using primer pair Pbr4_1/T1 yielded a fragment of 556 bp, and amplification of P. viticola with Pbr8/T1 yielded a fragment of 542 bp. One field isolate that showed the band profile of P. angustius/P. viticola, was identified as P. viticola (Table 1) after specific PCR amplification using primers Pbr8/T1 (lane 12 in Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

PCR amplifications using species-specific primers T1/Pr4_1 (A) and primers T1/Pr8 (B) to identify Phaeoacremonium angustius and Phaeoacremonium viticola, respectively. Lanes: M, molecular size markers (100 bp); 1, P. angustius (CBS114992); 2, P. angustius (CBS 114991); 3, P. viticola (CBS101738); 4, P. viticola (CBS113065); 5, P. parasiticum (CBS860.73); 6, P. aleophilum (CBS 246.91); 7, P. inflatipes (CBS391.71); 8, P. mortoniae (CBS101585); 9, P. krajdenii (CBS 109479); 10, P. venezuelense (CBS651.85); 11, P. scolyti (CBS113597); 12, P. viticola (field isolate).

DISCUSSION

The objective of this work was to develop a PCR-based strategy to detect and identify Phaeoacremonium species isolated from grapevines. This method consists basically of a genus-specific amplification of the ITS1/5.8S/ITS2 region of rDNA and a further digestion to obtain a discriminant profile of the species. Nowadays, there is no other detection method described than the traditional one consisting of isolating fungi from a sample wood on a rich medium, even though the detection of Phaeoacremonium is important, especially for sanitation programs in grapevine nurseries. Primers (Pal1N/Pal2) for detection of Phaeoacremonium aleophilum, the most common species causing Petri disease, are available (33), but the sequences of these primers are highly similar to the sequences of other Phaeoacremonium species (Fig. 4). Primer Pal2 has complete homology with P. mortoniae and P. angustius sequences and high similarity with the remaining species; the sequence of primer Pal1N also is greatly similar to the sequences of other species of this genus. Moreover, some isolates included in the taxon of P. aleophilum were recently redefined as new species (Phaeoacremonium alvesii [CBS110034] and Phaeoacremonium iranianum [CBS101357]) (25). For these reasons, these primers are not specific for the detection of P. aleophilum and are useless in its identification. Phaeoacremonium taxonomy has been extensively reviewed. In this study, 9 strains of 13 reported as growing on grapevines have been used. P. iranium and P. austroafricanum had not been described when this work was being carried out. P. subulatum is localized in South Africa, and P. australiense is found in Australia (25), and they were not included in this study. The method was evaluated for the remaining nine species (Table 1). DNA from each of the 38 isolates of Phaeoacremonium spp. was specifically amplified using the Pm1/Pm2 primer pair and it did not amplify DNA from other fungi collected from grapevines. More important, these primers recognized the new species of Phaeoacremonium defined when this work was being carried out (P. scolyti, P. krajdenii, and P. venezuelense). Therefore, these primers can be used to detect species of Phaeoacremonium infecting grapevines.

Two important advantages of using PCR for Phaeoacremonium detection are rapidity and sensitivity, qualities that are relevant when dealing with this pathogen. This fungus grows very slowly on enriched growth medium (25), which makes detection lengthy. This also means that Phaeocremonium is usually overgrown by other pathogens or saprobes, which may hide positive results of detection. Comparison of traditional and PCR methods to detect Phaeocremonium showed that the latter has greater sensitivity. Although the same amount of wood was used in a petri dish for fungal isolation and DNA extraction, PCR detected a higher number of infected fragments obtained from each plant (Table 3). Analysis was performed in 6 hours (extraction and PCR), while culturing and subsequent fungal isolation took up to 20 to 30 days and misidentification was not ruled out.

An effective measure to manage Petri disease is the use of pathogen-free plants in new vineyards (12, 32), and it is especially important, since it has been shown that infected plants are being used in new vineyards (1, 13, 15, 20). PCR amplifications carried out from wood extract are being performed to detect Phaeomoniella chlamydospora (16, 28, 33), the other important pathogen associated with Petri disease (4). It has been used to detect this pathogen in rootstocks and grapevine propagation plants (30), and it has shown the potential sources of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in plant nurseries (29). Similarly, implementation of the method presented here is suitable for production of Phaeoacremonium-free grapevine plants. The advantage of using designed, genus-specific primers is obvious, since there are several potential species of Phaeoacremonium occurring in a grapevine plant. If species-specific primers were to be used, a sanitation program for plant production could be much longer and expensive. Usage of the fungus-specific primer ITS1F (14) in the primary PCR prevents plant DNA amplification when detection is in wood.

All Phaeoacremonium species were unambiguously identified on the basis of their RFLP pattern, with the exception of Phaeoacremonium angustius and Phaeoacremonium viticola. However, when GenBank sequences of these two species (Table 1) were initially digested with a software application, results showed that it was possible that they were distinguished by digestion of the ITS region. Only after negative results in their differentiation were found, the sequences of ITS1F/ITS4-amplified region of P. viticola isolates (CBS101738 and CBS113065) were obtained, corroborating that the ITS sequences of P. viticola and P. angustius species exhibit 100% similarity. Similarity in ITS sequences was reported (17), which contributed to some misidentifications of these two species when P. viticola was defined as a new species (17). We conclude that the GenBank sequence of P. viticola (GenBank accession no. AF118137) is not right.

Taxonomy of Phaeoacremonium is difficult and slow. Basically, species are identified by cultural characters and morphology of conidia, conidiophores, and phialides. Since the genus was defined in 1996, new species have been included and described. Six species were originally included in the taxon that may be infecting grapevines, but this total number has nowadays become 13, which makes identification more difficult if possible. An alternative molecular method based on PCR amplification of DNA using species-specific primers in the β-tubulin gene has been recently designed (25), but a single PCR amplification is needed to identify each species. Restriction enzymes have been shown to be a powerful tool in the identification of Phaeoacremonium species by digestion of the ITS region and β-tubulin gene (9, 33). It was used before taxonomy of the genus was revised, allowing the identification of some species of Phaeoacremonium, in particular P. parasiticum and P. inflatipes (9). Digestion patterns also revealed that the former ex-type culture of P. angustius (CBS249.95) and P. inflatipes isolate (CBS222.95) were contaminated with P. aleophilum (9).

The strategy presented in this work has demonstrated to be robust enough for identification at the species level. Isolate CBS651.85 (type species of Phaeoacremonium venezuelense and formerly Phaeoacremonium parasiticum) was originally identified as P. parasiticum on the basis of its restriction profile when it was amplified with primers ITS4/ITS5 and digested with enzyme HhaI. This isolate has been used in this study, and it is clearly differentiated from P. parasiticum on the basis of RFLP patterns of Pm1/Pm2-amplified ITS region (Fig. 2).

The pathogenicity of Phaeoacremonium species is not yet fully established. Symptoms were reproduced by inoculation of Phaeoacremonium aleophilum (19, 21, 31), P. inflatipes (22), P. krajdenii, P. parasiticum, P. subulatum, P. venezuelense, and P. viticola (21). The other species were isolated from grapevines, but their pathogenicity has not been demonstrated. The identification of species becomes an important issue in disease management, especially when pathogenesis varies with the species. The method presented here is relatively simple compared to the traditional method that requires detailed observation of morphological characters and expertise evaluation of some characters, such as the type of phialides (24, 25). This method identifies all species of Phaeoacremonium in a maximum of three reaction mixtures. In summary, the PCR-based strategy presented here provides rapid, sensitive, and accurate detection and identification of Phaeoacremonium species in grapevines.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lizel Mostert for helpful information on CBS strains.

This research was supported in part by project RTA03-058-C2-2 (Programa Nacional de Recursos y Tecnologías Agrarias, Ministerio de Educación y Ciencia, Spain). Angeles Aroca was supported by a grant from INIA.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 9 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aroca, A., F. Garcia-Figueres, L. Bracamonte, J. Luque, and R. Raposo. 2006. A survey of trunk disease pathogens within rootstocks of grapevines in Spain. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 115:195-202. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bertelli, E., L. Mugnai, and G. Surico. 1998. Presence of Phaeoacremonium chlamydosporum in apparently healthy rooted grapevine cuttings. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 37:79-82. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Crous, P. W., W. Gams, M. J. Wingfield, and P. S. Van Wyk. 1996. Phaeoacremonium gen. nov. associated with wilt and declining diseases of woody host and human infections. Mycologia 88:786-796. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crous, P. W., and W. Gams. 2000. Phaeomoniella chlamydospora gen. et. comb. nov., a causal organism of Petri grapevine decline and esca. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 39:112-118. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Damm, U., and P. H. Fourie. 2005. A cost-effective protocol for molecular detection of fungal pathogens in soil. S. Afr. J. Sci. 101:135-139. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dubos, B. 2002. Maladies cryptogamiques de la vigne. Editions Feret, Bourdeaux, France.

- 7.Dupont, J., W. Laloui, and M. F. Roquebert. 1998. Partial ribosomal DNA sequences show an important divergence between Phaeoacremonium species isolated from Vitis vinifera. Mycol. Res. 102:631-637. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupont, J., W. Laloui, S. Magnin, P. Larignon, and M. F. Roquebert. 2000. Phaeoacremonium viticola, a new species associated with Esca disease of grapevine in France. Mycologia 92:499-504. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dupont, J., S. Magnin, C. Désari, and M. Gatica. 2002. ITS and β-tubulin markers help delineate Phaeoacremonium species, and the occurrence of Pm. parasiticum in grapevine disease in Argentina. Mycol. Res. 106:1143-1150. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards, J., and I. G. Pascoe. 2004. Occurrence of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium aleophilum associated with Petri disease and esca in Australian grapevines. Australas. Plant Pathol. 33:273-279. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fourie, P., and F. Halleen. 2002. Investigation on the occurrence of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in canes of rootstock mother vines. Australas. Plant Pathol. 31:425-426. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fourie, P., and F. Halleen. 2004. Proactive control of Petri disease of grapevine through treatment of propagation material. Plant Dis. 88:1241-1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fourie, P., and F. Halleen. 2004. Occurrence of grapevine trunk disease pathogens in rootstock mother plants in South Africa. Australas. Plant Pathol. 33:313-315. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gardes, M., and T. D. Bruns. 1993. ITS primers with enhanced specificity for basidiomycetes—application to the identification of mycorrhizae and rusts. Mol. Ecol. 2:113-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Giménez-Jaime, A., A. Aroca, R. Raposo, J. García-Jiménez, and J. Armengol. 2006. Occurrence of fungal pathogens associated with grapevine nurseries and the decline of young vines in Spain. J. Phytopathol. 154:598-602. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Groenewald, M., D. U. Bellstedt, and P. W. Crous. 2000. A PCR-based method for the detection of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in grapevines. S. Afr. J. Sci. 96:42-46. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Groenewald, M., J. C. Kang, and P. W. Crous. 2001. ITS and β-tubulin phylogeny of Phaeoacremonium and Phaeomoniella species. Mycol. Res. 105:651-657. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guarro, J., S. H. Alves, J. Gené, N. A. Grazziotin, R. Mazzuco, C. Dalmagro, J. Capilla, L. Zaror, and E. Mayayo. 2003. Two cases of subcutaneous infection due to Phaeoacremonium spp. J. Clin. Microbiol. 41:1332-1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gubler, W. D., A. Eskalen, A. J. Feliciano, and A. Khan. 2001. Susceptibility of grapevine pruning wounds to Phaeomoniella chlamydospora and Phaeoacremonium spp. Phytopathol. Mediterr. (Suppl.) 40:482-483. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Halleen, F., P. W. Crous, and O. Petrini. 2003. Fungi associated with healthy grapevine cuttings in nurseries, with special reference to pathogens involved in the decline of young vines. Australas. Plant Pathol. 32:47-52. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Halleen, F., L. Mostert, and P. W. Crous. 2005. Pathogenicity testing of Phialophora, Phialophora-like, Phaeoacremonium and Acremonium species isolated from vascular tissues of grapevines, p. 58. Fourth International Workshop on Grapevine Trunk Disease. University of Stellenbosch, Stellenbosch, South Africa.

- 22.Khan, A., C. Whiting, S. Rooney, and W. D. Gubler. 2000. Pathogenicity of three species of Phaeoacremonium spp. on grapevine in California. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 39:92-99. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Larignon, P., and B. Dubos. 1997. Fungi associated with esca disease in grapevine. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 103:147-157. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mostert, L., J. Z. Groenewald, R. C. Summerbell, V. Robert, D. A. Sutton, A. A. Padhye, and P. W. Crous. 2005. Species of Phaeoacremonium associated with infections in humans and environmental reservoirs in infected woody plants. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1752-1767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mostert, L., J. Z. Groenewald, R. C. Summerbell, W. Gams, and P. W. Crous. 2006. Taxonomy and pathology of Togninia (Diaporthales) and its Phaeoacremonium anamorphs. Stud. Mycol. 54:1-115. [Google Scholar]

- 26.O'Donnell, K., and E. Cigelnik. 1997. Two divergent intragenomic rDNA ITS2 types within a monophyletic lineage of the fungus Fusarium are nonorthologous. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 7:103-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pearson, R. C., and A. C. Goheen. 1998. Phomopsis cane blight and leaf spot, p. 17-18. In R. C. Pearson and A. C. Goheen (ed.), Compendium of grape diseases. APS Press, St. Paul, MN.

- 28.Retief, E., U. Damm, J. M. van Niekerk, A. McLeod, and P. H. Fourie. 2005. A protocol for molecular detection of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in grapevine wood. S. Afr. J. Sci. 101:139-142. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Retief, E., A. McLeod, and P. H. Fourie. 2006. Potential inoculum sources of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in South African grapevine nurseries. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 115:331-339. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridgway, H. J., B. E. Sleight, and A. Stewart. 2002. Molecular evidence for the presence of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in New Zealand nurseries, and its detection in rootstock mothervines using species-specific PCR. Australas. Plant Pathol. 31:267-271. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sparapano, L., G. Bruno, C. Ciccarone, and A. Graniti. 2000. Infection of grapevines by some fungi associated with esca. II. Interaction among Phaeoacremonium chlamydosporum, Phaeomoniella aleophilum and Fomitiporia punctata. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 39:125-133. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Surico, G. 2001. Towards commonly agreed answers to some basic questions on esca. Phytopathol. Mediterr. (Suppl.) 40:487-490. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tegli, S., E. Bertelli, and G. Surico. 2000. Sequence analysis of ITS ribosomal DNA in five Pheoacremonium species and development of a PCR-based assay for the detection of P. chlamydosporum and P. aleophilum in grapevine tissue. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 39:134-149. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thompson, J. D., T. J. Gibson, F. Plewniak, F. Jeanmougin, and D. G. Higgins. 1997. The ClustalX windows interface: flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 24:4876-4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Niekerk, J. M., P. W. Crous, J. Z. Groenewald, P. H. Fourie, and F. Halleen. 2004. DNA phylogeny, morphology and pathogenicity of Botryosphaeria species on grapevines. Mycologia 96:781-798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Whiteman, S. A., M. V. Jaspers, A. Stewart, and J. J. Ridgway. 2002. Detection of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in soil using species-specific PCR. N. Z. Plant Protect. 55:139-145. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Whiteman, S. A., M. V. Jaspers, A. Stewart, and H. J. Ridgway. 2003. Identification of potential sources of Phaeomoniella chlamydospora in the grapevine propagation process. Phytopathol. Mediterr. 43:152-153. [Google Scholar]