Abstract

Most of the bacteria in drinking water distribution systems are associated with biofilms. In biofilms, their nutrient supply is better than in water, and biofilms can provide shelter against disinfection. We used a Propella biofilm reactor for studying the survival of Mycobacterium avium, Legionella pneumophila, Escherichia coli, and canine calicivirus (CaCV) (as a surrogate for human norovirus) in drinking water biofilms grown under high-shear turbulent-flow conditions. The numbers of M. avium and L. pneumophila were analyzed with both culture methods and with peptide nucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) methods. Even though the numbers of pathogens in biofilms decreased during the experiments, M. avium and L. pneumophila survived in biofilms for more than 2 to 4 weeks in culturable forms. CaCV was detectable with a reverse transcription-PCR method in biofilms for more than 3 weeks. E. coli was detectable by culture for only 4 days in biofilms and 8 days in water, suggesting that it is a poor indicator of the presence of certain waterborne pathogens. With L. pneumophila and M. avium, culture methods underestimated the numbers of bacteria present compared to the FISH results. This study clearly proved that pathogenic bacteria entering water distribution systems can survive in biofilms for at least several weeks, even under conditions of high-shear turbulent flow, and may be a risk to water consumers. Also, considering the low number of virus particles needed to result in an infection, their extended survival in biofilms must be taken into account as a risk for the consumer.

The presence of pathogenic microbes in drinking waters is a significant health risk for drinking water consumers. In Finland, for example, waterborne epidemics in drinking water are typically caused by thermophilic campylobacteria or enteric viruses (11, 14, 26). Noroviruses are the causative agents in most of the viral waterborne outbreaks (22). Opportunistic pathogens like Mycobacterium avium inhabiting, and possibly growing in, water systems may cause a potential health risk, especially for immunocompromised patients (7). Legionella pneumophila growing in water systems can infect consumers, and others can be exposed via aerosols dispersed from different water systems, including hot- and cold-water showers and taps (9). According to the European Union drinking water directive, drinking water should not contain any microorganisms in numbers that constitute a potential danger to human health (29). Compliance to this directive is monitored using quality standards for Escherichia coli and other indicator bacteria.

Most of the bacteria in drinking water distribution systems are associated with biofilms growing on the inner surfaces of the pipelines, even under conditions of low- or high-shear water velocity, depending on the flow rate needs of the network. There are several studies showing that pathogenic or opportunistic pathogenic microbes can survive longer and have greater resistance to chlorine when occurring in biofilms than in drinking water (3, 20, 31, 44). In biofilms, the nutrient supply for bacteria is better, and bacteria are protected against disinfection (31). Also, viruses can attach to biofilms and remain infectious for a long time (43).

When assessing the risk of the microbial contamination in drinking water, it is crucial to obtain reliable results rapidly. Traditionally, pathogenic bacteria are detected by culture methods. Culture methods do not require special equipment, and bacteria detected with these methods are viable and active. However, sometimes, only a very small fraction of the bacteria in the environment are culturable, even when they are still viable, resulting in the concept of the viable but nonculturable form of survival (4, 33, 40). This means that culture methods are likely to underestimate the real number of bacteria that are able to cause infections. The second drawback is that the time required for results may vary from 1 day to several weeks for different microorganisms because of differences in growth rates (e.g., for slowly growing mycobacteria). Methods based on molecular biology, such as analyzing PCR products, give accurate data regarding the occurrence of the bacteria. However, DNA-based methods do not show the viability of the bacteria, and basic methods are only qualitative and not quantitative. Also, these methods are not always more sensitive than traditional culture methods (35) and are vulnerable to inhibitory compounds like humic acids and cations, especially if the water sample is concentrated (35, 42).

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) is based on the specific binding of nucleic acid probes to specific regions on rRNA. The use of rRNA-targeted oligonucleotide probes with detectable marker molecules enables the visualization of whole cells and the identification and study of microbes in situ (1). Traditionally, FISH methods are based on the use of conventional DNA oligonucleotide probes containing around 20 bases. Recently, FISH methods have been developed using fluorescently labeled peptide nucleic acid (PNA) probes targeting specific rRNA gene sequences. PNA molecules are DNA mimics, where the negatively charged sugar-phosphate backbone is replaced by an achiral, neutral polyamide backbone formed by repetitive units of N-(2-aminoethyl)glycine. Furthermore, PNA probes have been found to penetrate better through the hydrophobic cell wall of microorganisms than traditional DNA probes (46). There are now published PNA FISH methods for the rapid confirmation of several pathogenic bacteria (2, 17, 18, 32, 45, 50).

We studied the survival of several pathogenic bacteria in drinking water biofilms under conditions high-shear turbulent flow with traditional culture methods and with FISH. We also studied the persistence of viruses in biofilms. For the virus study, a canine calicivirus (CaCV) that can be grown in cell culture to high titers was used as a surrogate for human norovirus.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Microbial strains.

M. avium strain E89 was isolated from fresh stream water. The strain was grown to stationary phase in Middlebrook 7H9 broth (Difco) at 35°C for 11 days. The suspension was centrifuged (15 min at 1,650 × g in Sorvall GLC-3 centrifuge), and cells were washed with 0.9% (wt/vol) NaCl and resuspended in autoclaved drinking water. An environmental L. pneumophila strain, serogroup 5, was isolated from a tap distributing both cold and hot water (strain 2226A). The strain was cultured on buffered charcoal-yeast extract agar (BCYEα) medium for 2 days, and the suitable concentration of legionellae in an inoculum (autoclaved drinking water) was measured with a spectrophotometer (A420) (UV-1601; Shimadzu); the concentration of viable cells was also determined by cultivation. E. coli was isolated from contaminated drinking water during a waterborne outbreak in eastern Finland in August 2001 (11). The strain was grown in nutrient broth no. 2 (Oxoid) at 36°C for 24 h. The suspension was prepared similarly to the method described above for M. avium. CaCV strain 48 was kindly supplied by M. Koopmans (RIVM, Bilthoven, The Netherlands) by permission of F. Roerink (Kyoritsu Shoji Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) (36). A CaCV stock was grown in a continuous canine kidney (MDCK) cell line at the University of Helsinki.

Biofilms and spiking.

A Propella (Xenard; Mechanique de Precision, Seichamps, France) reactor (30) was placed in a containment cabinet with a separate ventilation system, and wastewaters were disinfected with chlorine before draining to the sewer. Before spiking, the Propella reactor with polyvinyl chloride coupons inside was run with Kuopio City tap water for 1 month. The temperature in the reactor was 15°C on average. Water was circulated inside the Propella reactor, and the Reynolds number for water flow was over 15,000; i.e., the water flow was turbulent. Water flow through the Propella reactor was 183 ml/h, with the volume of the reactor being 2.3 liters (retention time, 12.6 h). Biofilms were spiked with previously studied test bacterial strains by running the reactor with water containing the bacteria at approximately105 CFU/ml for 2 h. This was done to facilitate the adherence of cells to preexisting biofilms before water started to pump through the reactor (183 ml/h) and washout of nongrowing or slowly growing planktonic cells was commenced. Each strain of spiked microorganisms was studied in separate experiments. The CaCV concentration in the reactor was analyzed 2 h after the spiking, and it was 4.5 × 106 PCR units/ml.

Biofilm analyses.

Biofilm samples were taken five to six times during the 2- to 4-week period. During sampling, three parallel coupons were removed, and bacteria were detached from the coupons by 2 min of sonication in 25 ml of ultrapure water. For FISH analyses, 1 ml of the suspension was pelleted on the bottom of an Eppendorf tube by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min). The supernatant was removed, and bacteria were fixed with 80% (vol/vol) (for M. avium) or 90% (vol/vol) (for L. pneumophila) ethanol. After fixation, bacteria were pelleted by centrifugation, ethanol was removed, and the cells were resuspended in hybridization solution. The hybridization solution contained 10% (wt/vol) dextran sulfate (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO), 10 mM NaCl (Sigma), 30% (vol/vol) formamide (Sigma), 0.1% (wt/vol) sodium pyrophosphate (Sigma), 0.2% (wt/vol) polyvinylpyrrolidone (Sigma), 0.2% (wt/vol) Ficoll (Sigma), 5 mM disodium EDTA (Sigma), 0.1% (vol/vol) Triton X-100 (Sigma), 50 mM Tris HCl (Sigma), and 200 nM PNA probe (45). For M. avium, we used the 6-carboxyfluorescein-labeled MAV148 PNA probe (18), and for L. pneumophila, we used 6-carboxytetramethylrhodamine-labeled probe PLPNE620 (50). Bacteria were hybridized for 90 min at 55°C (L. pneumophila) or 59°C (M. avium). Subsequently, bacteria were pelleted and washed with prewarmed washing buffer for 30 min at the same temperature as that used for the hybridization. Bacteria were rinsed with washing buffer and finally eluted into 50 μl particle-free water, which was air dried on Teflon-coated multispot microscope slides (Erie Scientific Company). Hybridized bacteria were detected with an Olympus BX-51 TF epifluorescence microscope (Olympus Co. Ltd., Japan) and counted using an ocular grid.

For analyzing culturable M. avium, the detached biofilm suspension was decontaminated for 15 min at room temperature with cetylpyridinium chloride (final concentration, 0.005% [wt/vol]). After 15 min of centrifugation (8,600 × g), 30 ml of sterile deionized water was mixed with the pellet and centrifuged again. The pellet was resuspended in 200 μl of sterile deionized water and spread plated onto Mycobacterium 7H11 agar supplemented with Middlebrook OADC enrichment (Difco). Plates were incubated for up to 4 weeks at 35°C. Colonies were identified as being M. avium by using the PNA FISH method described above. For culturable L. pneumophila, aliquots of detached biofilm suspension were inoculated either directly, after acid wash (pH 2.2, 4 min), or after heat treatment (50°C, 30 min) onto BCYEα and GVPC media (13). One milliliter of suspension was also further concentrated by centrifugation (6,000 × g for 10 min), supernatant was removed, and the remaining 0.1 ml was heat treated and inoculated onto different Legionella-supporting media. Plates were incubated for 10 days at 36°C, and colonies were identified according to ISO standard 11731 (13). E. coli counts were analyzed using a membrane filtration method (41) using mEndo Agar LES medium (Merck) and 0.45-μm membranes (HAWG 047 S1; Millipore). Sample volumes were modified from 0.01 ml to 20 ml using sterile distilled water as a carrier liquid.

For CaCV analyses, detached biofilm suspensions were transferred to the virology laboratory at 4°C, where a sample of 2.2 ml was ultrafiltrated by using a microconcentrator (Centricon-100, Cuno; Amicon) to reach an estimated volume of 150 μl. Viral RNA extraction was performed with an RNA Viral Mini kit (QIAGEN), and 140 μl was used as an initial volume. RNA was eluted to a final volume of 60 μl. The cDNA was transcribed according to a method described previously (21). Real-time gene amplification was performed using a SYBR green I kit (QIAGEN) and melting curve analysis with a real-time machine (LightCycler; Roche). Primers CaCV-3 (5′-ACCAACGGAGGATTGCCATC-3′ [nucleotides 393 to 410 according to the sequence found under GenBank accession no. AF053720]) and CaCV-4 (5′-TAGCCGATCCCACAAGAAGACA-3′ [nucleotides 452 to 474]), specific for CaCV strain 48, were used.

Heterotrophic bacteria in detached biofilms were analyzed with a spread-plating method on R2A agar (Difco). Plates were incubated for 7 days at 22°C before colony counting. The total number of bacteria was analyzed with DAPI (4′,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole) staining, where the sample was collected by filtration on black 0.2-μm Nuclepore membranes (Whatman) and stained with 5 μg DAPI/ml stain for 15 min. All biofilm results were normalized to the amount of surface area (cm2).

Water.

Water samples (200 to 1,000 ml) were taken from the inlet and outlet of the Propella reactor at the same time as the biofilm samples. For M. avium and L. pneumophila, the water was filtered through a membrane filter (Ultipor NR047100, pore size of 0.2 μm; Pall Corp.). For culturable M. avium analyses, retained bacteria were detached from the filter by shaking with 6 ml of the original water filtrate in the presence of glass beads. The concentrated water sample was analyzed in the same way as described above for biofilms. For the FISH analyses, an aliquot (25 μl) of the concentrated bacterial suspension was pipetted onto Teflon-coated diagnostic microscope slides (Erie Scientific Company). Bacteria in the air-dried smear were hybridized with the MAV148 PNA probe as described above. Hybridized bacteria were counted with the epifluorescence microscope as described above.

For L. pneumophila analyses, bacteria collected on the filter (as described above) were detached from the filter into 5 ml of 1/40 Ringer's solution. Portions of concentrated samples were inoculated onto GVPC medium either directly, after acid wash, or after heat treatment. One milliliter of concentrate was also further concentrated by centrifugation, and the remaining 0.1 ml was either directly inoculated or heat treated and then inoculated onto GVPC. Water samples were also directly inoculated onto GVPC without concentration. BCYEα medium was used only after acid wash treatment in concentrated water samples. Incubation of the plates and identification were done according ISO standard 11731 (13). Bacteria in the air-dried smear (done as described above for M. avium) were hybridized with the PLPNE620 PNA probe and counted with the epifluorescence microscope as described above.

E. coli counts were analyzed in a same way as they were analyzed from biofilms except that the sample volumes were modified from 0.001 ml to 1,000 ml.

Heterotrophic bacteria and total number of bacteria were analyzed as described above for biofilms. Assimilable organic carbon (AOC) was analyzed using a modification of the van der Kooij (48) method (25). Microbially available phosphorus (MAP) was analyzed with a bioassay (16). Total organic carbon (TOC) was analyzed by a high-temperature combustion method with a Shimadzu 5000 TOC analyzer. Free residual chlorine was analyzed with a Palinest Micro 1000 chlorometer (Palintest Ltd., England).

Statistical analyses.

The statistical differences for the log-transformed results for biofilms and water were analyzed using the independent-sample t test with the SPSS 13.0 program for Windows. Results are calculated as geometric means and their geometric standard deviations. Pearson correlations were calculated with the SPSS 13.0 program for Windows.

RESULTS

The inlet water quality in Propella reactors during the experiments is presented in Table 1. There were some differences in the concentrations of microbial nutrients (AOC, MAP, and TOC) and the heterotrophic plate counts (HPC) in inlet water, but these changes were not statistically significant. No M. avium, L. pneumophila, E. coli, or CaCV was found in the inlet water of the Propella reactor or in biofilms taken before spiking. Biofilms in the Propella reactor had reached the steady state before spiking with the studied microbes. The geometric mean (n = 17 to 20) numbers of HPC in biofilms were 105 CFU/cm2 during E. coli and L. pneumophila experiments and 2 × 105 CFU/cm2 during M. avium and CaCV experiments. The geometric mean (n = 17 to 20) total numbers of bacteria in biofilms were, on average, 2.4 × 105 cells/cm2 during the E. coli experiments, 1.9 × 106 cells/cm2 during the M. avium experiment, 5.4 × 105 bacteria/cm2 during the CaCV experiment, and 2.2 × 105 bacteria/cm2 during the L. pneumophila experiment.

TABLE 1.

Propella inlet water quality during spiking experiments

| Organism(s) | Mean ± SD (no. of observations)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOC (μg/liter) | TOC (mg/liter) | MAP (μg/liter) | Chlorine (mg/liter) | HPC (CFU/ml) | Total bacteria (cells/ml) | pH | |

| E. coli and M. avium | 101 ± 53 (5) | 3.0 ± 0.3 (4) | 0.07 ± 0.07 (5) | 0.16 ± 0.03 (5) | 2,700 ± 300 (6) | 72,200 ± 37,100 (5) | 8.1 ± 0.4 (5) |

| L. pneumophila | 90 ± 22 (2) | 2.9 ± 0.1 (3) | 0.15 ± 0.08 (2) | 0.15 ± 0.01 (3) | 970 ± 190 (4) | 65,600 ± 27,200 (4) | 8.1 ± 0.1 (3) |

| CaCV | 75 ± 10 (5) | 3.4 ± 0.1 (4) | 0.14 ± 0.11 (5) | 0.14 ± 0.05 (5) | 7,300 ± 9,600 (5) | 70,300 ± 1,300 (3) | 8.2 ± 0.1 (5) |

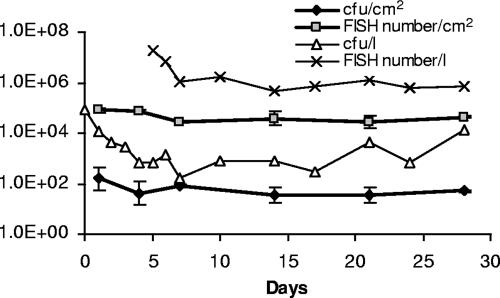

The number of M. avium cells in biofilms was monitored for 4 weeks. During this time, the number of culturable M. avium CFU in biofilms decreased from 155 CFU/cm2 to 50 CFU/cm2 (P > 0.05) on average, and the number of the bacteria obtained with FISH decreased from 8 × 104 cells/cm2 to 4.2 × 104 cells/cm2 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 1). In water, the number of culturable M. avium cells decreased markedly during first week after the 2-h initial adherence period and replacement of the test culture suspension with tap water. After that, the number of culturable M. avium cells started to increase slightly (Fig. 1). During the experiment, the number of culturable M. avium cells in water decreased from 8.9 × 104 CFU/ml to 1.3 × 104 CFU/ml (Fig. 1). Also, the number of M. avium cells analyzed with FISH in water decreased strongly during the experiment (there are no results for the water from the first 4 days) (Fig. 1). In biofilms, the number of M. avium cells obtained with the FISH method was on average 870 times higher (P < 0.001) than the number of culturable M. avium cells. In outlet water, the FISH number was on average 5,000 times higher (P < 0.001) than that obtained with the culture method. However, the culturability of M. avium in the outlet water increased during the experiment. Five days after spiking, the FISH number was 25,000 times higher than that obtained with culturing, but at the end of the experiment, it was only 60 times higher. There was no correlation between FISH results and the number of culturable M. avium cells in biofilms or in outlet water.

FIG. 1.

Numbers of M. avium cells in biofilms and outlet waters of the Propella reactor. Numbers of M. avium cells were analyzed with a culture method (CFU) and with FISH. In biofilm analyses, there is a geometric mean of three replicate samples, with geometric standard deviations indicated by the error bars. Labels for the y axis are indicated in inset legends.

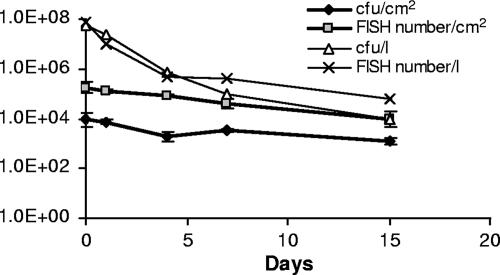

During the 2-week experimental period, the number of culturable L. pneumophila cells in biofilms decreased from 8,800 CFU/cm2 to 1,200 CFU/cm2 on average (P < 0.05), and the number of L. pneumophila cells analyzed with FISH decreased from 1.7 × 105 cells/cm2 to 9.3 × 103 cells/cm2 on average (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2). The number of culturable L. pneumophila cells in outlet water of the Propella reactor decreased from 5.9 × 107 CFU/liter to 104 CFU/liter, and the number of bacteria obtained with FISH decreased from 7.4 × 107 cells/liter to 6.1 × 104 cells/liter (Fig. 2). In biofilms, the number of bacteria analyzed with FISH was on average 21 times higher (P < 0.001) than that obtained with culturing. In outlet water, the number of bacteria was on average three times higher with FISH than that found with culturing. The culturability of L. pneumophila cells in outlet water decreased during the experiment. In the first few days (days 0 to 4), the number of L. pneumophila cells in the water was nearly the same when detected either with the culture method or by FISH, but at the end of the experiment, FISH analysis gave a number of bacteria that was six times higher than that detected with standard culture methods. In biofilms, the culturability of L. pneumophila did not vary significantly. The number of cultured L. pneumophila cells correlated with the FISH number in both biofilms (r = 0.85; P < 0.001; n = 14) and outlet water (r = 0.96; P < 0.01; n = 5). The number of culturable L. pneumophila cells in biofilms correlated (r = 0.90; P < 0.05; n = 5) with the number of culturable L. pneumophila cells in outlet water of the Propella reactor.

FIG. 2.

Numbers of L. pneumophila cells in biofilms and outlet waters of the Propella reactor. Numbers of L. pneumophila cells were analyzed with a culture method (CFU) and with FISH. For biofilm analyses, there is a geometric mean of three replicate samples, with geometric standard deviations indicated by the error bars. Labels for the y axis are indicated in inset legends.

The number of culturable E. coli cells in biofilms decreased rapidly. There were no culturable E. coli bacteria in biofilms taken later than 4 days after the spiking (Fig. 3). Also, in the outlet water, the number of the bacteria decreased rapidly, and after 8 days, it was not possible to detect any E. coli in the water anymore (Fig. 3). The rate of decrease of the number of E. coli cells in outlet water was almost similar to that in the theoretical washout (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Numbers of culturable E. coli cells in biofilms and outlet waters of the Propella reactor. For biofilm analyses, there is a geometric mean of three replicate samples, with geometric standard deviations indicated by error bars. Labels for the y axis are indicated in inset legends.

The number of CaCV PCR units in biofilms decreased from 1.9 × 105 PCR units/cm2 to 1.5 × 105 PCR units/cm2 (P > 0.05) during the 4-week experimentation period (Fig. 4). In the outlet water of the Propella reactor, the number of PCR units decreased from 9 × 106 PCR units/ml to 103 PCR units/ml during the experiment (Fig. 4). The decrease was strongest in the first week, when the number of PCR units decreased by 2 logs.

FIG. 4.

Concentrations of CaCV analyzed as PCR units in biofilms and outlet waters of the Propella reactor. For biofilm analyses, there is a geometric mean of three replicate samples, with geometric standard deviations indicated by error bars. Labels for the y axis are indicated in inset legends.

DISCUSSION

Our study proved that M. avium and L. pneumophila bacteria and caliciviruses were able to survive in biofilms for at least 2 to 4 weeks under high-shear turbulent-flow conditions. Also, during the experiments, these microbes were always found in the outlet waters of the reactor; they were not found in inlet water. The survival time of microbes in outlet water is longer than that predicted by the theoretical washout model and indicates that the microbes in the outlet water are released from the biofilms. It is considered to be unlikely that the extended presence of the spiked bacterial species in the outlet water was due to growth in the planktonic phase, given the low incubation temperature of the fermenter and the doubling time that they could achieve in this low-nutrient environment. The number of E. coli cells decreased rapidly in both biofilms and outlet water of the Propella reactor.

These results confirmed previous studies showing the survival of the M. avium (8, 28) and L. pneumophila (37, 38, 39, 49) in biofilms under conditions of less turbulent flow. Bacteria survived well in biofilms even though they were not adapted to grow on their own in an oligotrophic environment like drinking water. However, E. coli survived only a few days in biofilms and was found for only 8 days in the outlet water of the reactor, which did not differ significantly from theoretical washout from the system. The longer survival time of E. coli in water than in biofilms can be explained by different detection limits of the methods; in water, it is possible that the volume of the sample could increase more than was possible to achieve for biofilm samples. Our results agree with previous studies showing poor survival of E. coli in drinking water distribution systems (20, 23). This suggests that E. coli is not a good indicator of certain pathogenic bacteria in biofilms.

We analyzed E. coli only with the culture method, and the culturability of E. coli is known to be sensitive to low amounts (0.1 mg/liter) of chlorine (12, 23). In our study, the chlorine concentration of the inlet water of the Propella reactor was 0.15 mg/liter on average, which probably negatively affected the survival of E. coli in biofilms. Furthermore, Williams and Braun-Howland (51) previously found that culture methods for E. coli often produced negative results, while bacteria were still found with FISH. In previous work, we found that with the FISH method, it was possible to detect an intestinal bacterial pathogen, Campylobacter jejuni, in biofilms for at least 1 week, but with culture methods, they were detected only 2 h after spiking (19). This means that it is possible that there could still be some E. coli bacteria in biofilms even though it was not detected with the culture methods.

Our study proves that the number of the bacteria detected with culture methods highly underestimates the real number of bacteria in biofilms or in water. For M. avium, the number of bacteria detected with FISH was 1 to 4 logs higher than that detected by the culture method and was on average 1 log higher for L. pneumophila. Långmark et al. (15) found previously that the ratio of culturable cells to FISH-positive cells in a pilot distribution system varied between 0.002% and 65%. The real numbers of bacteria can be even higher, because we found previously that in FISH analyses, a proportion of the bacterial population is always lost during the hybridization and washing steps (19). One important reason for the low number of culturable bacteria is the decontamination of the samples before culturing. For example, for mycobacteria, there is a cetylpyridinium chloride decontamination step, which may also destroy some unknown but significant proportion of the M. avium bacteria, as has been shown previously (6, 24). It is not known if the bacteria detected with FISH are still viable. Typically, the physiological state of the bacteria affects the content of rRNA in bacterial cells and thus can affect signal intensity; i.e., highly fluorescent cells are in the active growth phase (27). In the study reported previously by Williams and Braun-Howland (51), it was found that chlorination decreased the hybridization efficacy of E. coli. Conversely, Prescott and Fricker (34) suggested that rRNA exists in the cell long after cell death and that rRNA cannot be used to assess the viability of the cells. However, in our study, the fluorescence intensities of the hybridized cells were not studied, as this requires tools like flow cytometry (10), which were not available for this study.

We found that the culturability of M. avium and L. pneumophila was not constant during the study. During the experiment, the culturability of M. avium increased. This could be attributed to an adaptation of M. avium to live in water and biofilms. The adaptation of the bacteria was also seen in the numbers of culturable M. avium cells in outlet water, which started to increase at the end of the experiment. However, in this study, we found that the culturability of L. pneumophila in outlet water decreased during the experiment. Långmark et al. (15) found previously that in biofilms, the culturability of L. pneumophila decreased strongly during the 38-day research period. This agrees with our findings regarding outlet water of the Propella reactor but is not supported by our results with biofilms, where the culturability of L. pneumophila did not change significantly during the experiment.

The number of CaCVs in biofilms decreased only 30% when analyzed as PCR units/cm2 in biofilms. In water, the concentration of viruses decreased more quickly but slower than the theoretical washout rate. This indicates that viruses were trapped in the biofilm and shed slowly. The infectivity of CaCV was not analyzed in this study. Viruses do not multiply outside their host cell, so their numbers can only decrease in the biofilms. For these experiments, viruses were grown in a continuous cell line, which may also produce many defective particles. Under suitable conditions, such as low temperature and chlorine concentration, viruses are stable for a long time. Noroviruses have, however, been shown to be even more stable than CaCVs (5). Generally, our results support previous findings showing that biofilms may accumulate viruses (43, 47).

In conclusion, microbes like M. avium, L. pneumophila, and caliciviruses may accumulate in biofilms, even under high-shear turbulent-flow conditions, but the commonly used indicator bacterium E. coli is not a proper indicator for these pathogens because it survives only a few days in biofilms. Also, this study clearly showed that standard culture methods may seriously underestimate the real numbers of bacteria in water and biofilms. The extended survival of the microbes in biofilms means that there is a risk that these bacteria may be released into cold and hot water and infect water consumers or others who are exposed. In the case of heavy microbial contamination of the distribution system, the removal of biofilms with some mechanical method such as the use of polyurethane swabs or compressed air-water flushing could be necessary to ensure the removal of pathogenic microbes from the distribution system.

Acknowledgments

This work is part of a SAFER: Surveillance and Control of Microbiological Stability in Drinking Water Distribution Networks Research project, which is supported by the European Commission within the Fifth Framework Programme “Energy, Environment, and Sustainable Development Program,” no. EVK1-2002-00108.

We are solely responsible for the work. The work presented does not represent the opinion of the Community, and the Community is not responsible for the use that might be made of the data appearing herein.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 2 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amann, R., F.-K. Glöckner, and A. Neef. 1997. Modern methods in subsurface microbiology: in situ identification of microorganisms with nucleic acid probes. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 20:191-200. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azevedo, N. F., M. J. Vieira, and C. W. Keevil. 2003. Establishment of a continuous model system to study Helicobacter pylori survival in potable water biofilms. Water Sci. Technol. 47(5):155-160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buswell, C. M., Y. M. Herlihy, L. M. Lawrence, J. T. M. McGuiggan, P. D. Marsh, C. W. Keevil, and S. A. Leach. 1998. Extended survival and persistence of Campylobacter spp. in water and aquatic biofilms and their detection by immunofluorescent-antibody and -rRNA staining. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:733-741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colwell, R. R., P. R. Brayton, D. J. Grimes, D. B. Roszak, S. A. Huq, and L. M. Palmer. 1985. Viable but non-culturable Vibrio cholerae and related pathogens in the environment: implications for release of genetically engineered microorganisms. Biotechnology 3:817-820. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Duizer, E., P. Bijkerk, B. Rockx, A. de Groot, F. Twisk, and M. Koopmans. 2004. Inactivation of caliciviruses. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:4538-4543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dundee, L., I. R. Grant, H. J. Ball, and M. T. Rowe. 2001. Comparative evaluation of four decontamination protocols for the evaluation of Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis from milk. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 33:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Falkinham, J. O., III. 1996. Epidemiology of infection by nontuberculous mycobacteria. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 9:77-215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Falkinham, J. O., III, C. D. Norton, and M. W. LeChevallier. 2001. Factors influencing numbers of Mycobacterium avium, Mycobacterium intracellularie, and other mycobacteria in drinking water distribution systems. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67:1225-1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fields, B. S., R. F. Benson, and R. E. Besser. 2002. Legionella and Legionnaires' disease: 25 years of investigation. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 15:506-526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fuchs, B. M., G. Wallner, W. Beisker, I. Schwippl, W. Ludwig, and R. Amann. 1998. Flow cytometric analysis of the in situ accessibility of Escherichia coli 16S rRNA for fluorescently labeled oligonucleotide probes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:4973-4982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hänninen, M.-L., H. Haajanen, T. Pummi, K. Wermundsen, M. L. Katila, H. Sarkkinen, I. Miettinen, and H. Rautelin. 2003. Detection and typing of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli and analysis of indicator organisms in three waterborne outbreaks in Finland. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:1391-1396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoff, J. C., and E. W. Akin. 1986. Microbial resistance to disinfectants: mechanisms and significance. Environ. Health Perspect. 69:7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.ISO. 1998. Water quality—detection and enumeration of Legionella. International standard 11731, 1998. ISO, Geneva, Switzerland.

- 14.Lahti, K., and L. Hiisvirta. 1995. Causes of waterborne outbreaks in community water systems in Finland: 1980-1992. Water Sci. Technol. 31(5-6):33-36. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Långmark, J., M. V. Storey, N. J. Ashbolt, and T.-A. Stenström. 2005. Accumulation and fate of microorganisms and microspheres in biofilms formed in a pilot-scale water distribution system. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71:706-712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lehtola, M. J., I. T. Miettinen, T. Vartiainen, and P. J. Martikainen. 1999. A new sensitive bioassay for determination of microbially available phosphorus in water. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:2032-2034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lehtola, M. J., C. J. Loades, and C. W. Keevil. 2005. Advantages of peptide nucleic acid oligonucleotides for sensitive site directed 16S rRNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) detection of Campylobacter jejuni, Campylobacter coli and Campylobacter lari. J. Microbiol. Methods 62:211-219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehtola, M. J., E. Torvinen, I. T. Miettinen, and C. W. Keevil. 2006. Fluorescence in situ hybridization using peptide nucleic acid probes for rapid detection of Mycobacterium avium subsp. avium and Mycobacterium avium subsp. paratuberculosis in potable-water biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:848-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lehtola, M. J., T. Pitkänen, L. Miebach, and I. T. Miettinen. 2006. Survival of Campylobacter jejuni in potable water biofilms: a comparative study with different detection methods. Water Sci. Technol. 54(3):57-61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackerness, C. W., J. S. Colbourne, P. J. Dennis, T. Rachwal, and C. W. Keevil. 1993. Formation and control of coliform biofilms in drinking water distribution systems, p. 217-226. In S. Denyer, S. P. Gorman, and M. Sussman (ed.), Society for Applied Bacteriology technical series, vol. 30. Microbial biofilms: formation and control. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, United Kingdom. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maunula, L., H. Piiparinen, and C.-H. von Bonsdorff. 1999. Confirmation of Norwalk-like virus amplicons after RT-PCR by microplate hybridization and direct sequencing. J. Virol. Methods 83:125-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maunula, L., I. T. Miettinen, and C.-H. von Bonsdorff. 2005. Norovirus outbreaks from drinking water. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 11:1716-1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McMath, S. M., C. Sumpter, D. M. Holt, A. Delanoue, and A. H. L. Chamberlain. 1999. The fate of environmental coliforms in a model water distribution system. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 28:93-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Metchock, B. G., F. S. Nolte, and R. J. Wallace, Jr. 1999. Mycobacterium, p. 399-438. In P. R. Murray, E. J. Baron, M. A. Pfaller, F. C. Tenover, and R. H. Yolken (ed.), Manual of clinical microbiology, 7th ed. American Society for Microbiology, Washington, DC.

- 25.Miettinen, I. T., T. Vartiainen, and P. J. Martikainen. 1999. Determination of assimilable organic carbon in humus-rich drinking waters. Water Res. 33:2277-2282. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Miettinen, I. T., O. Zacheus, C.-H. von Bonsdorff, and T. Vartiainen. 2001. Waterborne epidemics in Finland in 1998-1999. Water Sci. Technol. 43(12):67-71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Moter, A., and U. B. Göbel. 2000. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) for direct visualization of microorganisms. J. Microbiol. Methods 41:85-112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Norton, C. D., M. W. LeChevallier, and J. O. Falkinham III. 2004. Survival of Mycobacterium avium in a model distribution system. Water Res. 38:1457-1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Official Journal of the European Community. 1998. Council directive 98/83/EC of 3 November 1998 on the quality of water intended for human consumption. Off. J. Eur. Commun. 330:32-54. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Parent, A., S. Fass, M. L. Dincher, D. Reasoner, D. Gatel, and J.-C. Block. 1996. Control of coliform growth in drinking water distribution systems. J. Chart. Inst. Water E 10:442-445. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Percival, S. L., and J. T. Walker. 1999. Potable water and biofilms: a review of the public health implications. Biofouling 42:99-115. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Perry-O'Keefe, H., S. Rigby, K. Olivieira, D. Sørensen, H. Stender, J. Coull, and J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen. 2001. Identification of indicator microorganisms using a standardized PNA FISH method. J. Microbiol. Methods 47:281-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pommepuy, M., M. Butin, A. Derrien, M. Gourmelon, R. R. Colwell, and M. Cormier. 1996. Retention of enteropathogenicity by viable but nonculturable Escherichia coli exposed to seawater and sunlight. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 62:4621-4626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prescott, A. M., and C. R. Fricker. 1999. Use of PNA oligonucleotides for the in situ detection of Escherichia coli in water. Mol. Cell. Probes 13:261-268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riffard, S., S. Douglass, T. Brooks, S. Springthorpe, L. G. Filion, and S. A. Sattar. 2001. Occurrence of Legionella in groundwater: an ecological study. Water Sci. Technol. 43(12):99-102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roerink, F., M. Hashimoto, Y. Tohya, and M. Mochizuki. 1999. Organization of the canine calicivirus genome from the RNA polymerase gene to the poly(A) tail. J. Gen. Virol. 80:929-935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rogers, J., and C. W. Keevil. 1992. Immunogold and fluorescein labeling of Legionella pneumophila within an aquatic biofilm visualized by using episcopic differential interference contrast microscopy. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58:2326-2330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rogers, J., A. B. Dowsett, P. J. Dennis, J. V. Lee, and C. W. Keevil. 1994. The influence of temperature and plumbing material selection on biofilm formation and growth of Legionella pneumophila in potable water systems containing complex microbial flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1585-1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rogers, J., A. B. Dowsett, P. J. Dennis, J. V. Lee, and C. W. Keevil. 1994. The influence of plumbing materials on biofilm formation and growth of Legionella pneumophila in potable water systems containing complex microbial flora. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60:1842-1851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rowan, N. J. 2004. Viable but non-culturable forms of food and waterborne bacteria: quo vadis? Trends Food Sci. Technol. 15:462-467. [Google Scholar]

- 41.SFS. 2001. Water quality. Membrane filter technique for the enumeration of total coliform bacteria. SFS 3016. Finnish Standards Association, Helsinki, Finland.

- 42.Simpson, J. M., J. W. Santo Domingo, and D. J. Reasoner. 2002. Microbial source tracking: state of the science. Environ. Sci. Technol. 36:5279-5288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Skraber, S., J. Schijven, C. Gantzer, and A. M. de Roda Husman. 2005. Pathogenic viruses in drinking-water biofilms: a public health risk? Biofilms 2:105-117. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Steed, K. A., and J. O. Falkinham III. 2006. Effect of growth in biofilms on chlorine susceptibility of Mycobacterium avium and Mycobacterium intracellulare. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:4007-4011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Stender, H., K. Lund, K. H. Petersen, O. F. Rasmussen, P. Hoongmanee, H. Miörner, and S. E. Godtfredsen. 1999. Fluorescence in situ hybridization assay using peptide nucleic acid probes for differentiation between tuberculous and nontuberculous Mycobacterium species in smears of Mycobacterium cultures. J. Clin. Microbiol. 37:2760-2765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stender, H., M. Fiandaca, J. J. Hyldig-Nielsen, and J. Coull. 2002. PNA for rapid microbiology. J. Microbiol. Methods 48:1-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Storey, M. V., and N. J. Ashbolt. 2001. Persistence of two model enteric viruses (B40-8 and MS-2 bacteriophages) in water distribution pipe biofilms. Water Sci. Technol. 43(12):133-138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van der Kooij, D., A. Visser, and W. A. M. Hijnen. 1982. Determination of the concentration of easily assimilable organic carbon in drinking water. J. Am. Water Works Assoc. 74:540-545. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Van der Kooij, D., H. M. Veenendaal, and W. J. H. Scheffer. 2005. Biofilm formation and multiplication of Legionella in a model warm water system with pipes of copper, stainless steel and cross-linked polyethylene. Water Res. 39:2789-2798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wilks, S. A., and C. W. Keevil. 2006. Targeting species-specific low-affinity 16S rRNA binding sites by using peptide nucleic acids for detection of legionellae in biofilms. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72:5453-5462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Williams, M. M., and E. B. Braun-Howland. 2003. Growth of Escherichia coli in model distribution system biofilms exposed to hypochlorous acid or monochloramine. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5463-5471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]