Abstract

We investigate adaptive evolution of a quantitative trait under stabilizing selection with a moving optimum. We characterize three regimes, depending on whether (1) the beneficial mutation rate, (2) the fixation time, or (3) the rate of environmental change is the limiting factor for adaptation. If the environment is rate limiting, mutations with a small phenotypic effect are prefered over large mutations, in contrast to standard theory.

ADAPTATION is a key outcome of Darwinian evolution. However, only recently has adaptation become a focus of population genetics theory (reviewed by Orr 2005a,b). A number of robust predictions about the characteristics of “adaptive walks” (i.e., series of allelic substitutions leading to a high-fitness genotype) have been derived. Most studies (e.g., Gillespie 1983; Orr 1998, 2002) assume that selection is constant (arising from a sudden change in the environment) and strong relative to mutation (such that, most of the time, the population is fixed for one genotype, and the “steps” of the adaptive walk are well separated). Under these conditions, the probability that any one beneficial mutation is fixed during the next step of the adaptive walk is proportional to its selection coefficient (Gillespie 1983). For example, if there are two potential beneficial mutations with selection coefficients s1 and s2 (and equal mutation rates), the probability that the first mutation fixes in the next step is equal to s1/(s1 + s2). As a consequence, the average effect of mutations fixed during subsequent steps decreases exponentially (i.e., early steps are larger than later ones). This is true whether mutations are characterized by their selection coefficients (Orr 2002) or by their effects on the phenotype (Orr 1998).

In contrast, very little is known about adaptation if mutation is strong and the environmental change is gradual rather than sudden. However, two recent articles suggest that these factors can have a marked effect on the characteristics of adaptive walks. In a model of DNA sequence evolution, Kim and Orr (2005) analytically showed that, if mutation is strong and selection constant, the mutation with the largest selection coefficient will always fix first. In contrast, Bello and Waxman (2006) used a quantitative genetic approach to model adaptation of a polygenic trait under stabilizing selection with a moving optimum. These authors observed that, in an infinite population, beneficial mutations with small phenotypic effects tend to fix earlier than those with large effects. However, they found no such pattern for finite populations, and no explanation for the phenomenon was given.

Although the models by Kim and Orr (2005) and Bello and Waxman (2006) make rather different assumptions, they are similar in at least one important respect: Both assume that there is a small number of loci where a beneficial mutation can happen. This makes it possible to combine their two approaches. In this article, we analyze a two-locus version of the model by Bello and Waxman (2006) and subject it to an analysis similar to the one by Kim and Orr (2005). We investigate the order of fixation of two beneficial mutations as a function of the strength of mutation and the speed of the environmental change. We recover all three regimes—fixation probabilities proportional to the selection coefficients (Gillespie 1983), early fixation of large mutations (Kim and Orr 2005), and early fixation of small mutations (Bello and Waxman 2006)—in different areas of parameter space. We are also able to explain the different results by Bello and Waxman (2006) for finite vs. infinite populations. We conclude that the mutation rate and the speed of the environmental change are important determinants for the genetics of adaptation.

The model:

Following Bello and Waxman (2006), we analyze the evolution of a quantitative trait z under Gaussian stabilizing selection with an optimal phenotype zopt(t) that changes over time (cf. Bürger 2000). The fitness of an individual with phenotype z at time t is given by

|

(1) |

where σ > 0 determines the strength of selection. Due to changes in the external environment, the optimal phenotype zopt increases over time, according to

|

(2) |

with t*(v) = (zmax − zmin)/v. That is, between generations 0 and t*(v), zopt increases linearly from zmin to zmax at speed v. The case t* = 0 (  ) corresponds to a sudden jump in the optimal phenotype. In the following, without loss of generality, we set zmin = 0 and zmax = 1.

) corresponds to a sudden jump in the optimal phenotype. In the following, without loss of generality, we set zmin = 0 and zmax = 1.

We assume that the trait z is determined additively by two unlinked haploid loci. At each locus i, there are two alleles, a “wild-type” allele ai and a “mutant” allele Ai. ai can mutate to Ai (and vice versa) at rate μ. The contribution of the wild-type allele to the phenotype is 0 and the contribution of the mutant allele is αi. We assume that α1 ≤ α2, such that locus 1 is a “minor” locus and locus 2 a “major” locus. The corresponding mutant alleles A1 and A2 are referred to as being “small” and “large,” respectively. The aim of this article is to determine the probability, termed πsmall, that the small mutant allele goes to fixation before the large one. Following Bello and Waxman (2006), we define a mutant allele as being “fixed” once its frequency exceeds one-half.

To analyze this model, we use analytical approximations and stochastic simulations. We assume that individuals are hermaphroditic, generations are nonoverlapping, and the population has a constant size N. Simulations start at time t = 0, where the population is assumed to be monomorphic for the wild-type alleles a1 and a2. Each generation is modeled in two steps. First, we use deterministic equations to calculate the expected genotype frequencies (as in an infinite population) after selection (according to Equation 1), recombination (at rate 0.5 between loci), and mutation. Then, we use stochastic multinomial sampling to obtain the actual genotype frequencies in a finite population subject to genetic drift (e.g., Gillespie 1993; Kim and Orr 2005). This means that the next generation is obtained by drawing N individuals (with replacement) from the frequency distribution calculated in step 1. Simulations were performed in Gnu Octave (Eaton 1997). For the multinomial sampling, we used the gsl_rng_multinomial function from the Gnu Scientific Library (Galassi et al. 2005).

Results and discussion:

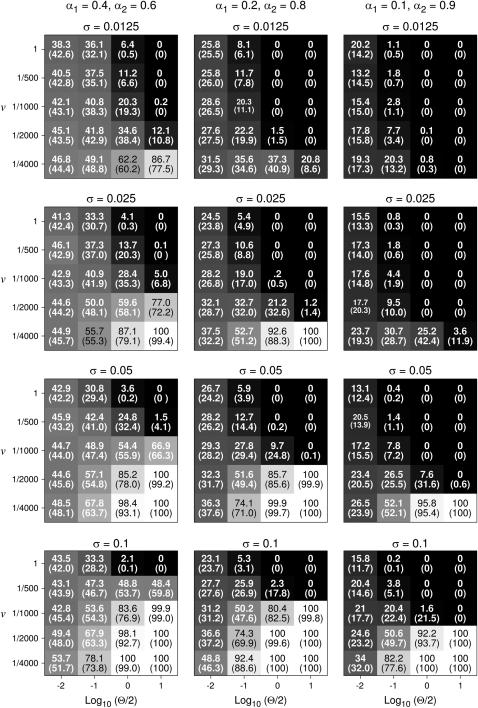

Figure 1 shows the probability πsmall that the mutant allele at the minor locus fixes first. If the optimum moves fast (high v), πsmall decreases if the population-wide mutation rate Θ = 2Nμ increases, in accordance with the results from Kim and Orr (2005). In sharp contrast, however, if the optimum moves slowly (small v) πsmall increases with increasing Θ. For fixed Θ, πsmall always increases with decreasing v and with increasing σ.

Figure 1.—

The probability πsmall (in percentage) of simulations where the mutant allele at the minor locus fixes before the mutant allele at the major locus, as a function of the population-wide mutation rate Θ/2 = Nμ (assuming μ = 10−5), the speed of the environmental change v, the selection strength σ, and the mutational effects of the two loci, α1 and α2. πsmall is also indicated by shades of gray, with black corresponding to 0% and white to 100%. The results are based on 1000 simulation for each parameter combination. Numbers in parentheses show the prediction from the analytical approximation (Equation A7). Similar results were obtained when N was fixed at 106 and μ varied between 10−8 to 10−5 (not shown).

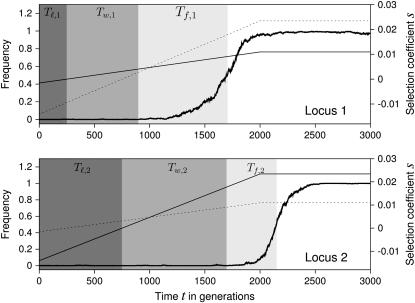

The essential parts of these results can be understood in a simple heuristic model. For this purpose, consider a typical simulation run, as in Figure 2. Three points are noteworthy:

At the beginning of the simulation, the mutant alleles are selected against, but as the optimal phenotype increases, they become beneficial. In particular, although the large mutant allele eventually reaches a higher selection coefficient than the small one, its initial selection coefficient is lower, and it becomes beneficial at a later time. That is, initially, the moving optimum favors small mutations over large ones.

At time t = 0, the population is fixed for the wild-type alleles, but the mutant alleles arise recurrently by mutation. Most of the new mutants are lost by drift (even if they are beneficial). Eventually, however, one successful allele is picked up by selection, sweeps through the population, and goes to fixation.

The actual fixation time is shorter for the large mutant allele because, once it has become beneficial, its selection coefficient increases faster.

Figure 2.—

Example simulation run, in which the mutant allele at the minor locus (locus 1) fixes first. In each plot, the thick solid line shows the frequency of the mutant allele at the respective locus, and the thin solid line shows the selection coefficient s (in the approximation A5) over time. The dotted line shows the selection coefficient for the other locus. Shading marks the time periods used in the analytical approximation. Tl is the lag time during which the mutant allele is deleterious, Tw is the waiting time for a successful mutation, and Tf is the fixation time (i.e., the time until the mutant allele reaches frequency 0.5). Note that Tl,1 < T l,2 but Tf,1 > Tf,2. Parameters: α1 = 0.25, α2 = 0.75, μ = 10−5, N = 104, σ = 0.025, v = 1/2000.

In summary, the time until a mutant allele (at a single locus) becomes fixed can be subdivided into three periods: The lag time Tl during which the allele is deleterious, the waiting time Tw for a successful allele, and the fixation time Tf. Ignoring interactions between loci (which may arise due to linkage disequilibrium or epistasis for fitness) the probability πsmall can be expressed as

|

(3) |

where 𝒫 stands for probability.

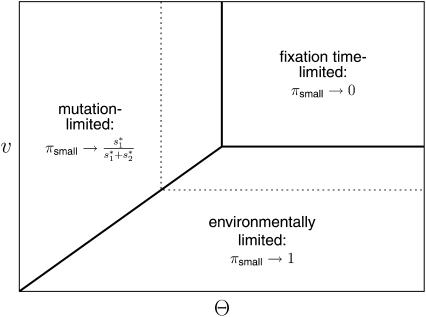

To leading order in our basic model parameters, Tl is proportional to 1/v (i.e., the lag times are long if the optimum moves slowly), Tw is proportional to 1/(Θσ) (the waiting times are long if mutation rates are low or selection is weak), and Tf is approximately proportional to 1/σ (fixation times are long if selection is weak). These terms define three different time scales, all of which can potentially limit the rate of adaptation and determine the order of fixations. By focusing on the extreme cases where one time scale dominates the other two, we can define three regimes, which, together, provide a qualitative explanation of the simulation results. They are summarized in Figure 3.

Figure 3.—

Schematic overview of the behavior of πsmall as a function of the population-wide mutation rate, Θ, and the speed of the environmental change, v. As outlined in the main text, there are three main regimes, depending on the dominating time scale (i.e., on which of the three time periods in Figure 2 is longest). The dotted line shows how the boundaries of the regimes shift as the selection parameter σ becomes smaller.

The mutation-limited regime:

If the waiting time for a successful mutation is much larger than both the lag time and the fixation time (Tw ≫Tl, Tf; Θσ ≪ σ, v), we recover Gillespie's (1983) classical result that the order of fixation depends on the relative selection coefficients (see appendix).

The fixation time-limited regime:

If, in contrast, the dynamics of adaptation are dominated by the fixation times ( ), the mutant allele at the major locus, whose fixation time is shorter, will always fix first (see Kim and Orr 2005).

), the mutant allele at the major locus, whose fixation time is shorter, will always fix first (see Kim and Orr 2005).

The environmentally limited regime:

Finally, if the dynamics are dominated by the lag time until a mutation becomes beneficial ( )—that is, if the rate of adaptation is limited by the rate of environmental change—the small mutant allele at the minor locus always fixes first, because it is the first to become selected for.

)—that is, if the rate of adaptation is limited by the rate of environmental change—the small mutant allele at the minor locus always fixes first, because it is the first to become selected for.

To validate this qualitative picture, we have derived a quantitative analytical approximation that is based on the above arguments (see appendix). As shown in Figure 1 (numbers in parentheses), the predictions from this approximation are in good agreement with the simulation results.

Bello and Waxman (2006), when analyzing a model similar to ours (but with multiple loci), found that small alleles tend to fix first in an infinite population but not in a finite one. From our results and the parameters used in their simulations, we conclude that the infinite population (which has Tw = 0) was in the environmentally limited regime, whereas the finite population (with Θ = 2 × 0.1) was in the transition zone between the environmentally limited and the mutation-limited regime, where the order of fixations already has a large variance.

Conclusions:

The aim of this short note was to understand the first steps of the adaptive process when the selection pressure increases gradually over time. In particular, we were interested in the order of fixation of “major” and “minor” alleles that differ in their effect on the phenotype. To this end, we have constructed a minimal model that contains all essential ingredients, but still allows for an analytical treatment. We find that three time scales are relevant for the problem: the lag time (defining the time for an allele to become beneficial), the waiting time for a successful beneficial mutation, and the fixation time. Depending on the biological parameters, each of these time scales may dominate and, thus, defines a dynamic regime with specific properties. So far, extensive theory exists only for one of these regimes, where mutation is limiting. The common view that major alleles predate minor alleles in the substitution process is based on this assumption. Our results show that the opposite is true if the rate of adaptive evolution is limited by the rate of environmental change.

Our model can—and should—be extended in many ways. In particular, it will be interesting to see quantitative predictions for traits with multiple loci, diploid genetics, and different patterns of linkage and epistasis. We expect, however, that the main qualitative result of this study, the existence of the three regimes, will remain robust. The important empirical question then is to determine the adaptive regime for the response to a specific selection pressure. Given the huge variances in natural population sizes, selection pressures, and environmental rates of change, it seems likely that examples in all three regimes will be found.

Acknowledgments

We thank C. Dillmann, P. Pennings, P. Pfaffelhuber, and an anonymous reviewer for helpful comments on the manuscript. This study was supported by an Emmy-Noether grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to J.H.

Note added in proof: A shift of adaptive substitutions toward smaller step sizes for slow rates of environmental change is also found in a recent simulation study on the evolution of RNA secondary structure by Collins et al. [S. Collins, J. de Meaux and C. Acquisti, 2007, Adaptive walks toward a moving optimum, Genetics 176 (in press)].

APPENDIX: THE ANALYTICAL APPROXIMATION FOR πsmall

In this Appendix, we show how to calculate the right-hand side of Equation 3. In a wild-type background, the selection coefficients for the mutant alleles are

|

(A1) |

With zopt(t) = vt (t < t*), it follows that the lag time during which the mutant is deleterious (si < 0) is

|

(A2) |

For the fixation time Tf,i of a beneficial mutant allele, we ignore the variance and assume a constant maximal selection pressure  = si(

= si( ). We can then use the result for the average fixation time from Hermisson and Pennings (2005) (with an extra factor one-half, since we census at 50% allele frequency),

). We can then use the result for the average fixation time from Hermisson and Pennings (2005) (with an extra factor one-half, since we census at 50% allele frequency),

|

(A3) |

The variation in the total time to fixation (Tl + Tw + Tf) for a beneficial allele comes from the waiting time for a successful mutation, Tw,i. We therefore need a stochastic approach for this component. Mutant alleles Ai arise recurrently at rate Θ/2. We use the simplifying assumption that the fate of each new mutation—fixation or loss—is decided in a short time period during which we can assume a constant selection pressure. The fixation probability is almost zero as long as the allele is deleterious and approximately 2si(t) as soon as it becomes beneficial (Haldane 1927; Crow and Kimura 1970). Successful mutations then appear according to an inhomogeneous Poisson process with time-dependent rate Θsi(t). In particular, the probability that a successful mutation has not yet appeared at time t, 1 − Fi, follows the differential equation

|

(A4) |

with si(t) ≡ 0 for t < Tl,i. Note that the cumulative distribution function of Tw,i is given by  For τ = t − Tl,i > 0 and weak selection, we can approximate the selection coefficient as

For τ = t − Tl,i > 0 and weak selection, we can approximate the selection coefficient as

|

(A5) |

where  − T l,i. The differential equation (A4) can then be solved (with the initial condition Fi(Tℓ,i) = 0) to yield

− T l,i. The differential equation (A4) can then be solved (with the initial condition Fi(Tℓ,i) = 0) to yield

|

(A6a) |

for 0 < τ ≤ τ* and

|

(A6b) |

for τ > τ*. Finally, πsmall can be calculated (by numerical integration) as

|

(A7) |

where  is the probability density function of Tw,1, and δf = Tf,1 − Tf,2 and δl = T l,2 − Tl,1 are the differences in fixation time and lag time between the two loci. Note that δf acts as a “penalty” for the A1 allele and δl as a penalty for the A2 allele.

is the probability density function of Tw,1, and δf = Tf,1 − Tf,2 and δl = T l,2 − Tl,1 are the differences in fixation time and lag time between the two loci. Note that δf acts as a “penalty” for the A1 allele and δl as a penalty for the A2 allele.

If the environmental change is very fast ( also implying

also implying  ), Equation A6b reduces to Fi(Tl,i + τ) = 1 − exp(– Θ

), Equation A6b reduces to Fi(Tl,i + τ) = 1 − exp(– Θ  τ) and Equation A7 can be evaluated to

τ) and Equation A7 can be evaluated to

|

(A8) |

(cf. Kim and Orr 2005, Equation 8). As pointed out by Kim and Orr (2005), in this case, πsmall approaches  ) for

) for  (mutation-limited regime; see Gillespie 1983) and 0 for

(mutation-limited regime; see Gillespie 1983) and 0 for  (fixation time-limited regime).

(fixation time-limited regime).

The approximations we have used in the above calculations lead to small or moderate deviations from the simulation results. In particular, our use of the maximal selection coefficient  in Equation A3 leads to a consistent underestimate of the fixation times Tf,i and to a slight shift of the boundary between the fixation time-limited and environmentally limited regimes toward higher values of v.

in Equation A3 leads to a consistent underestimate of the fixation times Tf,i and to a slight shift of the boundary between the fixation time-limited and environmentally limited regimes toward higher values of v.

References

- Bello, Y., and D. Waxman, 2006. Near-periodic substitutions and the genetic variance induced by environmental change. J. Theor. Biol. 239: 152–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bürger, R., 2000. The Mathematical Theory of Selection, Recombination, and Mutation. Wiley, Chichester, UK.

- Crow, J. F., and M. Kimura, 1970. An Introduction to Population Genetics Theory. Harper & Row, New York.

- Eaton, J., 1997. GNU Octave Manual, Ed. 3. Network Theory Ltd., Bristol, UK.

- Galassi, M., J. Davies, J. Theiler, B. Gough, G. Jungman et al., 2005. GNU Scientific Library Reference Manual, Ed. 2. Network Theory Ltd., Bristol, UK.

- Gillespie, J. H., 1983. A simple stochastic gene substitution model. Theor. Pop. Biol. 23: 202–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie, J. H., 1993. Substitution processes in molecular evolution. I. Uniform and clustered substitutions in a haploid model. Genetics 134: 971–981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haldane, J. B. S., 1927. A mathematical theory of natural and artificial selection. V. Selection and mutation. Proc. Camb. Philos. Soc. 23: 838–844. [Google Scholar]

- Hermisson, J., and P. S. Pennings, 2005. Soft sweeps: molecular population genetics of adaptation from standing genetic variation. Genetics 169: 2335–2352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Y., and H. A. Orr, 2005. Adaptation in sexuals vs. asexuals: clonal interference and the Fisher–Muller model. Genetics 171: 1377–1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, A. H., 1998. The population genetics of adaptation: the distribution of factors fixed during adaptive evolution. Evolution 52: 935–949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, A. H., 2002. The population genetics of adaptation: the adaptation of DNA sequences. Evolution 56: 1317–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, A. H., 2005. a The genetic theory of adaptation: a brief history. Nat. Rev. Gen. 6: 119–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orr, A. H., 2005. b Theories of adaptation: what they do and don't say. Genetica 123: 3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]