Abstract

Protein serine/threonine phosphatase type 1 (PP1) has been found in all eukaryotes examined to date and is involved in the regulation of many cellular functions, including glycogen metabolism, muscle contraction, and mitosis. In Drosophila, four genes code for the catalytic subunit of PP1 (PP1c), three of which belong to the PP1α subtype. PP1β9C (flapwing) encodes the fourth PP1c gene and has a specific and nonredundant function as a nonmuscle myosin phosphatase. PP1α87B is the major form and contributes ∼80% of the total PP1 activity. We describe the first mutant alleles of PP1α96A and show that PP1α96A is not an essential gene, but seems to have a function in the regulation of nonmuscle myosin. We show that overexpression of the PP1α isozymes does not rescue semilethal PP1β9C mutants, whereas overexpression of either PP1α96A or PP1β9C does rescue a lethal PP1α87B mutant combination, showing that the lethality is due to a quantitative reduction in the level of PP1c. Overexpression of PP1β9C does not rescue a PP1α87B, PP1α96A double mutant, suggesting an essential PP1α-specific function in Drosophila.

ONE of the most widespread mechanisms of post-translational regulation of proteins is the addition of phosphate by protein kinases; this phosphorylation is antagonized by protein phosphatases. Reversible phosphorylation of proteins can regulate their activity, cellular location, or binding affinity. The antagonistic actions of protein kinases and protein phosphatases are of equal importance in determining the degree of phosphorylation of each substrate protein. Among the serine/threonine protein phosphatases, serine threonine protein phosphatase type 1 (PP1) forms a major class and is highly conserved among all eukaryotes examined to date (Lin et al. 1999). PP1 is involved in the regulation of many cellular functions, including glycogen metabolism, muscle contraction, and mitosis (reviewed in Bollen 2001; Cohen 2002; Ceulemans and Bollen 2004).

In Drosophila melanogaster, as in mammals, two PP1 subtypes exist: PP1α (homologous to mammalian PP1α and PP1γ) and PP1β (homologous to mammalian PP1δ, also known as PP1β). Three genes code for the PP1α isozyme and are named after their respective chromosomal location: PP1α13C (FlyBase: Pp1-13C), PP1α87B (Pp1-87B), and PP1α96A (Pp1α-96A). Only one gene, PP1β9C (flapwing, flw), encodes the PP1β type. The protein sequences of PP1α and PP1β are extremely similar (88% identity over the first 300 amino acids), yet the PP1α/β subtype difference is conserved in mammals (Dombrádi et al. 1993).

In vitro, the catalytic subunit of PP1 (PP1c) dephosphorylates a wide variety of substrates, but in vivo it is found complexed to a number of different proteins that modify its substrate activity and specificity and target it to specific locations. Such targeting and regulatory proteins are therefore key to investigating the role of PP1 in specific subcellular processes [e.g., glycogen metabolism through PTG (Printen et al. 1997) or Dpp receptor type 1 deactivation through Sara (Bennett and Alphey 2002)]. In a yeast two-hybrid assay for PP1c-binding proteins in Drosophila, we found that the large majority of PP1c-binding proteins bind all four PP1c isozymes (Bennett et al. 2006). Very few proteins have been identified that specifically bind some PP1c isozymes but not others. These include mammalian Neurabin I and Neurabin II/Spinophilin, which bind PP1α and PP1γ, but not PP1δ (MacMillan et al. 1999; Terry-Lorenzo et al. 2002), and Drosophila MYPT-75D, which binds PP1β, but not PP1α (Vereshchagina et al. 2004).

PP1α87B is the most abundant PP1c isozyme in Drosophila. In third instar larvae, PP1α87B contributes ∼80% of the total PP1 activity (Dombrádi et al. 1990). In PP1α87B heterozygous mutants, the total PP1 activity is decreased by 40% but viability is not affected (Dombrádi et al. 1990). PP1α87B homozygotes are lethal and show suppression of position-effect variegation, chromosome hypercondensation, and abnormal spindle structure (Axton et al. 1990; Dombrádi et al. 1990; Baksa et al. 1993).

PP1α13C is located within intron 4 of the gene abnormal chemosensory jump 6 (acj6). A loss-of-function deletion of part of acj6, which also removes PP1α13C, is homozygous viable. PP1α13C is therefore not an essential gene and has no unique essential function that is not redundant with the other PP1c genes. Deletion of acj6 affects the sensilla, maxillary palp sense organs, and the laminar plexus, causing chemosensitive behavior defects. These visual and behavioral defects of the acj6 deletion are not complemented by overexpression of PP1α13C cDNA (Clyne et al. 1999) and may therefore be entirely due to the deletion of acj6.

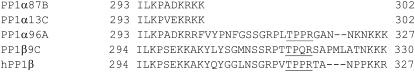

All mammalian PP1c proteins have a 25- to 27-amino acid C-terminal region that contains a cdk phosphorylation motif (T P P/Q R) (Ishii et al. 1996), the threonine residue of which (T320 in human PP1α) has been shown to be important for G1 progression in cell cycle (Berndt et al. 1997). In Drosophila PP1α, this region is retained in PP1α96A, but lost from PP1α87B and PP1α13C (Figure 1). This is the first study that genetically characterizes PP1α96A by mutational analysis, revealing a function in nonmuscle myosin regulation (see results).

Figure 1.—

Multiple-sequence alignment of the C termini of Drosophila PP1c and human PP1β (hPP1β). The amino acid sequences for PP1c are extremely conserved between the Drosophila PP1c proteins as well as Drosophila PP1c compared to human PP1 (Dombrádi et al. 1993). PP1α87B and PP1α13C have lost the C terminus, which contains a Cdk phosphorylation site (T P P/Q R).

Strong alleles of PP1β9C (PP1β9C6 and PP1β9C7) show failure in maintaining larval muscle attachment, have crumpled or blistered wings, and lack indirect flight muscles (IFMs). The weak and viable allele PP1β9C1 is flightless due to disorganized IFMs, but otherwise appears normal (Raghavan et al. 2000). The nonmuscle myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit MYPT-75D binds PP1β and targets it to its substrate, nonmuscle myosin regulatory light chain (Spaghetti squash, Sqh). Dephosphorylation of Sqh inhibits contraction mediated by the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain (nmmHC; Zipper, Zip). PP1β9C6 mutant clones have elevated levels of phospho-Sqh and presumably hyperactivated nmmHC. Mutations in genes that lead to downregulation of nmmHC activity, e.g., nmmHC, Rho, and RhoGEF2, rescue the semilethality of PP1β9C6, showing that regulation of nonmuscle myosin activity is the single essential function of PP1β9C (Vereshchagina et al. 2004). In contrast to most PP1c-binding proteins, MYPT-75D binds specifically to PP1β and not to PP1α (Vereshchagina et al. 2004), which may account for the specificity of the PP1β9C phenotypes and the genetic interactions between PP1β9C and genes involved in the regulation and function of cytoplasmic myosin.

In this study, we describe the first mutant alleles of PP1α96A and show that the gene is not essential. However, PP1α96A mutants enhance the weak, viable allele PP1β9C1 through nonmuscle myosin heavy chain, indicating that PP1α96A has a role in the regulation of nonmuscle myosin. We tested for redundancy between PP1α and PP1β by ubiquitously expressing PP1c in PP1β9C and PP1α87B mutant backgrounds, respectively. We show that overexpression of PP1α does not rescue the semilethality of PP1β9C6, whereas overexpression of PP1β does rescue the lethality of a PP1α87B mutant, showing that the lethality of PP1α87B is due to a quantitative reduction in the level of PP1c, rather than a PP1α87B-specific function in the development of Drosophila. However, expression of PP1β does not rescue a PP1α87B, PP1α96A mutant combination, which suggests that at least one essential process, possibly late metamorphosis, depends on PP1α function specifically.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly strains and genetics:

pUAS-HA-PP1c constructs were as previously described (Bennett et al. 2003). UAS-HA-PP1c insertions on the third chromosome were recombined with either arm-Gal4 or PP1α87B87Bg-3. w; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c males were crossed to w, PP1β9C6/FM7c virgin females to test for complementation of PP1β9C. w; PP1α87B87Bg-3, UAS-HA-PP1c/TM6B males were crossed to w; arm-Gal4; PP1α87B1/TM6B virgin females to test for complementation of PP1α87B. The PP1α87B1 chromosome is marked with e. PP1α96A1 was generated by the Drosophila Gene Search Project (Toba et al. 1999) and has a P{GSV6} insertion in the 5′-UTR of PP1α96A (line GS11179). The PP1α96A2 null mutant was generated by imprecise excision of PP1α96A1 with P{Δ2-3} transposase (Laski et al. 1986). The original PP1α96A1 chromosome was found to have at least one lethal mutation outside of the 96A region, which was removed by recombining it to ru, h, st, ry, e prior to the excision experiments, so the complete genotypes for PP1α96A1 and PP1α96A2 are ru, h, st, ry, e, PP1α96A1 and ru, h, st, ry, e, PP1α96A2, respectively.

Fly extracts and immunoblotting:

Flies were taken up and homogenized in 2× SDS sample buffer (100 mm Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 200 mm dithiothreitol, 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, bromophenol blue) and the proteins were separated by SDS–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (Sambrook et al. 1989). Separated proteins were transferred onto an Immobilon-P PVDF membrane (Millipore, Bedford, MA). The membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat powdered milk in PBST (137 mm NaCl, 3 mm KCl, 10 mm Na2HPO4, 2 mm KH2PO4, 0.1% Tween 20) and incubated with 1:1000 anti-HA 12CA5 (F. Hoffmann La-Roche) or 1:2000 anti-α-tubulin T9026 (Sigma, St. Louis) as a primary and 1:10,000 horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Sigma) as a secondary antibody. HRP was detected with Supersignal West Pico (Pierce, Rockford, IL) and blue-sensitive X-ray film (GRI).

Preparation of cDNA and RT–PCR:

Total RNA from third instar larvae or adult flies was extracted using Trizol (Invitrogen, San Diego) according to the manufacturer's instructions. cDNA was prepared using the SuperScript first-strand synthesis system for RT–PCR kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PP1α96A RT–PCR primers (CTGCGGGGAATTCGACAACG and TGTGTGTGTGGCCGTTTGTAG) anneal at the C terminus of PP1α96A, which is not deleted in PP1α96A2.

RESULTS

Mutagenesis and analysis of PP1α96A:

PP1α96A is not an essential gene:

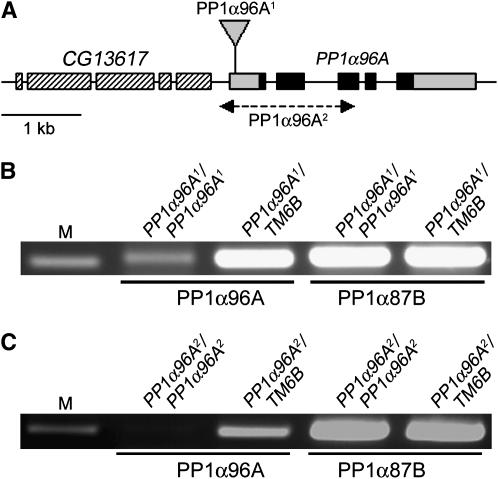

The role of PP1α96A has remained unclear because no mutants have been described. Therefore, we decided to generate mutants for this gene and found that one of the P{GSV6} elements from the Drosophila Gene Search Project (Toba et al. 1999) was inserted in the 5′-UTR of PP1α96A (Figure 2A). We named this allele PP1α96A1. The original PP1α96A1 chromosome was homozygous lethal; however, PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 flies were viable and without phenotype even though Df(3R)crb87-5 completely deletes PP1α96A (Wustmann et al. 1989; Kellerman and Miller 1992; our own molecular analysis, not shown). This suggested that the PP1α96A1 chromosome contained at least one additional and lethal mutation, but that PP1α96A1 itself might be viable. We exchanged the majority of the chromosome by generating a ru, h, st, ry, e, PP1α96A1 recombinant chromosome. This recombinant was homozygous viable and exhibited no obvious mutant phenotype apart from the markers, showing that we had removed a lethal mutation unrelated to PP1α96A1. P insertions in 5′-UTRs often reduce the transcription level of the respective gene. We therefore used RT–PCR to assess the transcript levels of PP1α96A in PP1α96A1 homozygous and heterozygous third instar larvae and found that the level of PP1α96A transcript was greatly reduced in PP1α96A1 homozygotes (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.—

(A) PP1α96A gene structure and mutants. Coding regions (black) and untranslated regions are indicated. The direction of transcription for CG13617 and PP1α96A is from left to right. PP1α96A1 is due to an insertion in the 5′-UTR of PP1α96A. PP1α96A2 is a 1.7-kb deletion that deletes the proximal promoter region, transcription start, and exons 1–3 of PP1α96A, but not the adjacent gene CG13617. (B) The level of PP1α96A transcript is reduced in PP1α96A1 homozygotes. (C) No PP1α96A transcript can be detected in PP1α96A2 homozygotes. M, marker (200-bp band).

We generated several deletion derivatives by imprecise excision of PP1α96A1 and molecularly analyzed their breakpoints. We found that one of these, PP1α96A2, was a deletion of 1.7 kb, which removed the proximal promoter region, transcription start, and exons 1–3 of PP1α96A, but not the adjacent gene CG13617 (Figure 2A). RT–PCR on extracts from PP1α96A2 homozygous and heterozygous flies failed to detect PP1α96A transcript in the homozygotes (Figure 2C); taking this with the molecular analysis of the deletion, we concluded that PP1α96A2 is a null allele for PP1α96A. PP1α96A2 is homozygous viable, fertile, and without any obvious phenotype, showing that PP1α96A is not an essential gene. Unlike PP1α87B, PP1α96A is not a suppressor of position-effect variegation (not shown).

Genetic interactions between PP1α96A and PP1α87B mutants:

We assume that PP1α96A contributes at most 10% of the total PP1 activity in Drosophila, as PP1α87B and PP1β9C contribute ∼80 and 10%, respectively (Dombrádi et al. 1990; Vereshchagina et al. 2004). Therefore, we wondered whether PP1α96A2 homozygotes might show a phenotype in a background of reduced total PP1c. We introduced PP1α87B87Bg-3/+, which lowers the total PP1 activity by 40%, into a PP1α96A2 background, but found that adult flies heterozygous for PP1α87B and homozygous for PP1α96A (PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/PP1α87B+, PP1α96A2) have normal viability and appearance (not shown). PP1α87B87Bg-3/PP1α87B1 trans-heterozygotes (which lack ∼80% of total PP1 activity) die during pupariation and, until pupariation, do not lag behind in development compared to their heterozygous siblings. We also examined flies lacking wild-type copies of both PP1α87B and PP1α96A (PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/PP1α87B1, and PP1α96A2). These mutants, which might lack as much as 90% of total PP1 activity, died slightly earlier than PP1α87B87Bg-3/PP1α87B1 and pupariated 1–2 days later than their siblings. This suggests a weak enhancement of PP1α87B by PP1α96A, although a possible effect of genetic background cannot be ruled out. The pupal lethality of PP1α87B mutants, with or without PP1α96A2, could indicate a high requirement for total PP1 or PP1α during metamorphosis.

PP1α96A enhances PP1β9C through zip:

Of the three PP1α genes in Drosophila, PP1α96A is the only one that has the conserved final 25–27 amino acids at its C terminus (Figure 1), but a related sequence is also present in PP1β9C. We therefore wondered whether a mutation in PP1α96A would genetically interact with PP1β9C. To test this, we used the weak allele PP1β9C1, which is viable but flightless due to defects in the indirect flight muscles (Raghavan et al. 2000). PP1β9C1/Y ; PP1α96A1/+ and PP1β9C1/Y ; Df(3R)crb87-5/+ were viable and do not exhibit any phenotype apart from rare defects in the posterior part of the wing (not shown). PP1β9C1/Y ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5, however, was completely lethal (Table 1), showing that PP1α96A indeed interacts genetically with PP1β9C. The enhancement of PP1β9C1 by PP1α96A is specific to PP1α96A and not due to an overall reduction of PP1 activity, because PP1β9C1/Y; PP1α87B87Bg-3/+ is viable (not shown).

TABLE 1.

PP1α96A is an enhancer of PP1β9C1 (from cross PP1β9C1/FM7 ; Df(3R)crb87-5/TM6B × PP1α96A1/PP1α96A1)

| F1 genotype | |

|---|---|

| PP1β9C1/Y ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 0 |

| PP1β9C1/Y ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 29 |

| FM7/Y ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 45 |

| FM7/Y ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 44 |

| PP1β9C1/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 55 |

| PP1β9C1/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 51 |

| FM7/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 65 |

| FM7/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 37 |

| Total | 326 |

The viable trans-heterozygous allelic combination PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 is lethal in a PP1β9C1 mutant background. Df(3R)crb87-5 completely removes PP1α96A. This shows that PP1α96A has an essential function in a PP1β9C1 mutant background.

Genetic interaction between different mutants often indicates that the genes act in the same pathway. Since PP1β9C has a single essential and nonredundant function as a nonmuscle myosin phosphatase, we wondered whether the lethality of PP1β9C1/Y; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 is due to a failure in nonmuscle myosin regulation and possibly to hyperactivation of nmmHC. To test this, we introduced the mutant zip1 into a PP1β9C1/Y; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 background and found that this rescued the lethality (Table 2), suggesting that the genetic interaction between PP1β9C and PP1α96A is indeed related to the role of PP1β9C in the regulation of nonmuscle myosin.

TABLE 2.

nmmHC (zip) suppresses the enhancement of PP1β9C1 by PP1α96A (from cross PP1β9C1/FM7 ; Df(3R)crb87-5/TM6B × zip1/CyO ; PP1α96A1/PP1α96A1)

| F1 genotype | |

|---|---|

| PP1β9C1/Y ; zip1/+ ; PP1A96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 10 |

| PP1β9C1/Y ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 0 |

| PP1β9C1/Y ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 12 |

| PP1β9C1/Y ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 16 |

| FM7/Y ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 18 |

| FM7/Y ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 3 |

| FM7/Y ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 3 |

| FM7/Y ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 5 |

| PP1β9C1/+ ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 10 |

| PP1β9C1/+ ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 20 |

| PP1β9C1/+ ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 10 |

| PP1β9C1/+ ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 23 |

| FM7/+ ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 16 |

| FM7/+ ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5 | 16 |

| FM7/+ ; zip1/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 7 |

| FM7/+ ; CyO/+ ; PP1α96A1/TM6B | 22 |

| Total | 191 |

A mutant copy of the nonmuscle myosin heavy chain zipper suppresses the lethality of PP1β9C1/Y ; PP1α96A1/Df(3R)crb87-5, suggesting that PP1α96A enhances PP1β9C1 through the known role of PP1β9C in nonmuscle myosin regulation.

Redundancy between PP1α and PP1β:

Overexpression of PP1α87B or PP1α96A does not complement PP1β9C:

Although the protein sequences of PP1α and PP1β are extremely similar (Dombrádi et al. 1993), they show structural differences that are also conserved in humans. This suggests that the two subtypes might have differential, nonredundant functions. To test for redundancy of PP1β, we expressed PP1α using the UAS/Gal4 system (Brand and Perrimon 1993) to see whether this would rescue the semilethal missense mutant PP1β9C6. The altered amino acid of PP1β9C6, Y133, is thought to form a hydrogen bond to the peptide backbone of the substrate (Egloff et al. 1997); PP1β9C6 protein is therefore likely to bind its substrates with lower affinity.

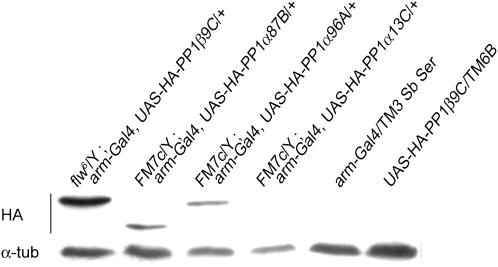

w PP1β9C6/FM7c virgin females were crossed to males of the genotype w; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c/TM6B. The presence of arm-Gal4 induces expression of UAS-HA-PP1c constructs throughout the fly and does not cause a phenotype. The expression level of UAS-HA-PP1α13C with arm-Gal4 was extremely low (<40 times lower than arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1α87B, not shown); therefore, UAS-HA-PP1α13C was not included in the complementation analysis. As expected, expressing HA-PP1β9C completely restored the viability (Table 3) as well as the wing phenotype (Raghavan et al. 2000) of PP1β9C6/Y males. However, PP1β9C6/Y could not be rescued by expression of HA-PP1α87B or HA-PP1α96A (Table 3, summarized in Table 5). Western Blots with α-HA showed clear expression of HA-PP1β9C and slightly lower levels of HA-PP1α87B and HA-PP1α96A (Figure 3). We subsequently found that the expression levels of HA-PP1α96A and HA-PP1β9C with arm-Gal4 were sufficient to complement a PP1α87B mutant, which showed that the expressed proteins are functional (see below).

TABLE 3.

Expressing HA-PP1c in a PP1β9C (PP1β9C6) mutant background (from cross w, PP1β9C6/FM7c × w ; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c/TM6B)

| F1 genotype | UAS-HA-PP1β9C | UAS-HA-PP1α87B | UAS-HA-PP1α96A |

|---|---|---|---|

| w, PP1β9C6/Y ; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c/+ | 47 | 0 | 1 |

| w, PP1β9C6/Y ; TM6B/+ | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| FM7c/Y ; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c/+ | 28 | 40 | 35 |

| FM7c/Y ; TM6B/+ | 9 | 17 | 30 |

| w, PP1β9C6/+ ; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c/+ | 46 | 37 | 37 |

| w, PP1β9C6/+ ; TM6B/+ | 20 | 33 | 44 |

| FM7c/+ ; arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c/+ | 48 | 48 | 35 |

| FM7c/+ ; TM6B/+ | 27 | 30 | 35 |

| Total | 225 | 206 | 218 |

PP1β9C6 is a strong, semilethal allele of PP1β9C. Overexpression of HA-PP1β9C rescues the semilethality of PP1β9C6, while overexpression of HA-PP1α does not, showing that PP1β9C is not functionally redundant with PP1α.

TABLE 5.

Summary of overexpression experiments

| Rescued by overexpression of arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PP1 mutant | PP1β9C | PP1α87B | PP1α96A | PP1α13C |

| PP1β9C6/Y | + | − | − | − |

| PP1α87B87Bg-3/PP1α87B1 | + | + | + | (−) |

The semilethal PP1β9C6 mutant was rescued by overexpression of PP1β9C (+) but not by overexpression of PP1α87B or PP1α96A (−). A lethal trans-heterozygous PP1α87B mutant was rescued by overexpression of PP1β9C, as well as PP1α87B and PP1α96A. Since the expression level of UAS-HA-PP1α13C was extremely low (see Figure 3), it was not included in the overexpression experiments in a PP1α87B mutant background. ND, not determined.

Figure 3.—

Expression levels of UAS-HA-PP1c with arm-Gal4 in the progeny of the crosses PP1β9C6/FM7c × arm-Gal4, UAS-HA-PP1c. Expressed levels of HA-PP1c were detected with anti-HA. The amount of expressed HA-PP1α13C is below detection levels. HA-PP1α87B has slightly higher mobility because of its shortened C terminus (see Figure 1). α-tub, α-tubulin.

Overexpression of PP1α96A and PP1β9C can rescue PP1α87B:

PP1α87B is the major PP1c isozyme in Drosophila and contributes ∼80% of the total PP1 activity (Dombrádi et al. 1990). We wondered whether PP1α87B has a specific and nonredundant role in the development of Drosophila, which cannot be performed by another PP1c. We tested this by expressing PP1α96A and PP1β9C in a PP1α87B mutant background, using the alleles PP1α87B1 and PP1α87B87Bg-3. PP1α87B1 is an EMS-induced hypomorphic point mutant with a single amino acid replacement (G220S) in a residue that is conserved in all protein serine/threonine phosphatases of the PP1/PP2A/PP2B family (Dombrádi and Cohen 1992). PP1α87B87Bg-3 is an amorphic mutant resulting from DNA rearrangement in the 5′-end of PP1α87B (Axton et al. 1990). PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3 trans-heterozygotes are lethal. w; arm-Gal4; PP1α87B1/TM6B female virgins were crossed to w; PP1α87B87Bg-3, UAS-HA-PP1c/TM6B males to generate flies that express HA-PP1c in a PP1α87B mutant background.

PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3 was rescued by overexpression of UAS-HA-PP1α87B with arm-Gal4, as expected, but also by overexpression of HA-PP1α96A or HA-PP1β9C (Table 4, summarized in Table 5). The rescued flies had a normal appearance (not shown). This indicated that PP1α96A and PP1β9C can substitute for PP1α87B in its absence and suggests that the lethality of PP1α87B mutants is due to a reduction of overall PP1 activity and not to an essential and nonredundant function of PP1α87B.

TABLE 4.

Expressing HA-PP1c in a PP1α87B (PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3) mutant background (from cross w ; arm-Gal4 ; PP1α87B1/TM6B × w ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, [UAS-HA-PP1c]/TM6B)

| F1 genotype | No UAS-HA-PP1c | UAS-HA-PP1α87B | UAS-HA-PP1α96A | UAS-HA-PP1β9C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3, [UAS-HA-PP1c] | 0 | 42 | 18 | 27 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3, [UAS-HA-PP1c] | 0 | 49 | 24 | 26 |

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B1/TM6B | 34 | 40 | 38 | 49 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B1/TM6B | 21 | 52 | 22 | 44 |

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, [UAS-HA-PP1c]/TM6B | 20 | 51 | 39 | 33 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, [UAS-HA-PP1c]/TM6B | 34 | 39 | 34 | 36 |

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; TM6B/TM6B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; TM6B/TM6B | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 109 | 273 | 175 | 215 |

PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3 is a lethal allelic combination of PP1α87B. Overexpression of HA-PP1α87B, HA-PP1α96A, and HA-PP1β9C rescues the lethality of PP1α87B1/PP1α87B87Bg-3, showing that HA-PP1α96A and HA-PP1β9C can substitute for the function of PP1α87B in a PP1α87B mutant background.

Overexpression of PP1β9C does not rescue PP1α87B, PP1α96A double mutants:

As shown above, expression of PP1β9C rescues a PP1α87B mutant. However, the presence of wild-type PP1α96A (and/or PP1α13C) in this background could mask an essential requirement for PP1α that PP1β could not perform. Therefore, we expressed PP1β9C in a PP1α87B, PP1α96A double-mutant background, by crossing w; arm-Gal4, PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/TM6B to w; UAS-HA-PP1β9C, PP1α87B1, PP1α96A2/TM6B. We found that overexpression of PP1β9C did not rescue the lethality of PP1α87B, PP1α96A double mutants (Table 6), indicating that Drosophila PP1α has at least one essential function that PP1β9C cannot perform, possibly during late metamorphosis, as PP1α87B, PP1α96A double mutants with arm-Gal4, PP1β9C die as late pupae.

TABLE 6.

Expressing HA-PP1β in a PP1α87B, PP1α96A mutant background (from cross w ; arm-Gal4 ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/TM6B × w ; UAS-HA-PP1β9C, PP1α87B1, PP1α96A2/TM6B)

| F1 genotype | |

|---|---|

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/UAS-HA-PP1β9C, PP1α87B1, PP1α96A2 | 0 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/UAS-HA-PP1β9C, PP1α87B1, PP1α96A2 | 0 |

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/TM6B | 46 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/TM6B | 48 |

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; UAS-HA-PP1β9C, PP1α87B1, PP1α96A2/TM6B | 48 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; UAS-HA-PP1β9C, PP1α87B1, PP1α96A2/TM6B | 48 |

| w/w ; arm-Gal4/+ ; TM6B/TM6B | 0 |

| w/Y ; arm-Gal4/+ ; TM6B/TM6B | 0 |

| Total | 190 |

Overexpression of HA-PP1β9C does not rescue the lethality of PP1α87B87Bg-3, PP1α96A2/PP1α87B1, or PP1α96A2. This suggests that HA-PP1β9C cannot substitute for the function of PP1α and that therefore there is an essential requirement for PP1α in Drosophila development.

DISCUSSION

Protein phosphatase 1, as well as the PP1α/PP1β subtype difference, is highly conserved between Drosophila and mammals. Humans have three PP1 genes: PP1α and PP1γ are homologs of the Drosophila PP1α genes, and PP1δ (also known as PP1β) corresponds to PP1β.

We show here that expression of HA-PP1α87B and HA-PP1α96A does not rescue a semilethal allele of PP1β, which further supports our previous conclusion that PP1β9C has an essential function that cannot be performed by PP1α (Vereshchagina et al. 2004). It also allows us to rule out an alternative explanation for the PP1β9C mutant phenotype—that PP1β9C, but none of the PP1α forms, is expressed in a specific subset of cells during fly development. The data above rule out this possibility, as overexpression of PP1α87B and PP1α96A did not rescue strong PP1β9C alleles, while expression of PP1β9C, under the control of the same driver, fully rescued the phenotype of PP1β9C6. The specific, nonredundant function of PP1β has been identified as regulation of nonmuscle myosin activity, possibly through the PP1β-specific interactor MYPT-75D (Vereshchagina et al. 2004). MYPT-75D is the fly homolog of mammalian MYPT3 (myosin phosphatase-targeting subunit) and is related to Mbs (myosin-binding subunit), which is the homolog of mammalian MYPT1 and MYPT2. Mbs regulates myosin activity by targeting PP1c to its substrate myosin regulatory light chain (Mizuno et al. 1999). Recently, it was shown that human MYPT3 co-immunoprecipitated with PP1δ, and phosphorylation of MYPT3 by protein kinase A activated PP1δ toward cytoplasmic myosin regulatory light chain (Yong et al. 2006).

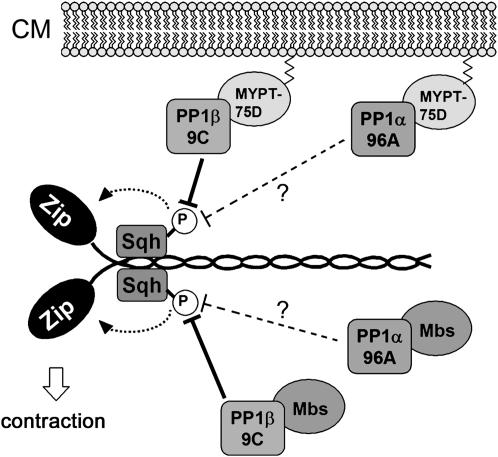

Of the four Drosophila PP1c genes, PP1α87B, PP1α13C, and PP1β9C have been previously characterized by mutational analysis (Axton et al. 1990; Clyne et al. 1999; Raghavan et al. 2000). By generating a viable and fertile null allele of PP1α96A, we found that PP1α96A is not an essential gene. It does, however, have an essential function in the PP1β9C1 mutant background, and this function probably relates to the regulation of nonmuscle myosin. PP1α96A, but not PP1α87B or PP1α13C, was able to bind to a fragment of MYPT-75D that lacked the N terminus in the yeast two-hybrid system (L. Alphey, unpublished results) although it did not bind to the whole MYPT-75D protein, whereas PP1β did (Vereshchagina et al. 2004). Thus, it is possible that PP1α96A may have a weak affinity to bind MYPT-75D and enhances PP1β by being partly redundant with it. Alternatively, PP1α96A could be partially redundant with PP1β9C through binding to Mbs. Studies on the crystal structure of the vertebrate PP1δ-MYPT1 complex suggest that the tyrosine residues Y305 and Y307 at the C terminus of chicken PP1δ are particularly important for its binding to the second ankyrin repeat of MYPT1 (Terrak et al. 2004). Y305 and Y307 are in the C-terminal part that PP1α87B and PP1α13C lack and are conserved in Drosophila PP1β (Y304 and Y306). PP1α96A has only one tyrosine residue at Y304, shifted by one amino acid compared to PP1β (Figure 1). The mammalian Mbs homologs MYPT1/2 seem to bind specifically to mammalian PP1β in vivo (Hartshorne 1998). Thus, even though all four Drosophila PP1c isozymes bind Mbs in the yeast two-hybrid system (Vereshchagina et al. 2004), it may be that the majority of nonmuscle myosin phosphatase complexes in vivo consist of PP1β9C/Mbs and a minority of PP1α96A/Mbs (Figure 4). Both models would explain why PP1α96A and not, for example, PP1α87B, enhance PP1β9C1: in a weak PP1β9C mutant background, PP1α96A would be able to compensate for partial loss of PP1β9C activity, but not in the strong and semilethal background of PP1β9C6.

Figure 4.—

Model for PP1α96A function in nonmuscle myosin regulation. Dephosphorylation of the nonmuscle myosin regulatory light chain (Sqh, Spaghetti Squash) inhibits the ATPase activity of nonmuscle myosin heavy chain (Zip, Zipper) and subsequent contraction. The major Sqh phosphatase PP1β9C is targeted to nonmuscle myosin by the nonmuscle myosin phosphatase-targeting subunits Mbs and MYPT-75D. MYPT-75D is prenylated and probably membrane associated. PP1α96A might have a weak affinity to Mbs and/or MYPT-75D and be partly redundant with PP1β9C. CM, cytoplasmic membrane.

Even though PP1 is involved in the regulation of numerous cellular processes, relatively little is known about specific and nonredundant functions of the different PP1c isozymes. In mice, PP1γ (probably the testis-specific splice variant PP1γ2) has a nonredundant function in spermatogenesis, as PP1γ knockout male mice are viable but sterile with defects in spermatogenesis, while knockout female mice are viable and fertile (Varmuza et al. 1999). Presumably, the somatic and female germline functions of PP1γ are redundant with PP1α and/or PP1δ. No knockout analysis exists for the other PP1c genes, although PP1α was shown to have a specific function in murine lung growth and morphogenesis (Hormi-Carver et al. 2004).

The conservation of the PP1α/β difference between flies and mammals suggests an ancient qualitative difference between the two subtypes. This raises the question of whether a PP1α-specific function exists that PP1β cannot perform. We found that expression of PP1α96A and PP1β9C could complement a lethal PP1α87B mutant, suggesting that the role of PP1α87B is essential because of its high expression levels rather than structural differences with the other PP1c isozymes. However, expression of PP1β9C did not rescue a PP1α87B, PP1α96A double mutant, suggesting that at least one developmental process in Drosophila depends on PP1α specifically.

Mammalian PP1α, PP1γ1, and PP1δ localize to distinct subcellular locations in mammalian cells (Andreassen et al. 1998; Trinkle-Mulcahy et al. 2001, 2003; Lesage et al. 2005). It is thought that such specific localization and function is mediated by regulators that bind the PP1c isozymes with different affinities. Neurabin I and Neurabin II/Spinophilin were identified to bind PP1γ1 and PP1α, but not PP1δ (MacMillan et al. 1999; Terry-Lorenzo et al. 2002), and several PP1α- and PP1γ1-specific regulators have been identified in mouse fetal lung epithelial cells (Flores-Delgado et al. 2005). In Drosophila, even though the majority of PP1c regulatory subunits seem to bind all four PP1c isozymes in the yeast two-hybrid system (Bennett et al. 2006), we identified three interactors that bind PP1α specifically or with greatly increased affinity compared to PP1β (L. Alphey, unpublished results). One of them, CG11416 (uri), is essential for viability (J. Kirchner and L. Alphey, unpublished results) and could mediate an essential requirement for PP1α.

In this study we show that PP1α96A is not an essential gene, but has an essential function in nonmuscle myosin regulation in a weak PP1β9C mutant background. Furthermore, we demonstrate by complementation analysis that PP1β9C has an essential function that is nonredundant with PP1α, while PP1α87B is essential only because of its high expression levels. Overexpressing PP1β9C does not rescue a PP1α87B, PP1α96A double mutant, indicating a PP1α-specific developmental function. Together, this sheds new light on the essential, redundant, and overlapping functions of the PP1c genes in Drosophila.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Karen Clifton for technical assistance and the Bloomington and Kyoto stock centers for providing the mutant fly strains. We also thank Helen White-Cooper for helpful discussion. This work was supported by grants from the United Kingdom Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council and the United Kingdom Medical Research Council. D.B. is a Todd Bird Research Fellow at New College, Oxford.

References

- Andreassen, P. R., F. B. Lacroix, E. Villa-Moruzzi and R. L. Margolis, 1998. Differential subcellular localization of protein phosphatase-1 alpha, gamma1, and delta isoforms during both interphase and mitosis in mammalian cells. J. Cell. Biol. 141: 1207–1215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axton, J. M., V. Dombradi, P. T. Cohen and D. M. Glover, 1990. One of the protein phosphatase 1 isoenzymes in Drosophila is essential for mitosis. Cell 63: 33–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baksa, K., H. Morawietz, V. Dombradi, M. Axton, H. Taubert et al., 1993. Mutations in the protein phosphatase 1 gene at 87B can differentially affect suppression of position-effect variegation and mitosis in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 135: 117–125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D., and L. Alphey, 2002. PP1 binds dSARA to antagonise Dpp signalling. Nat. Genet. 31: 419–423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D., B. Szoor, S. Gross, N. Vereshchagina and L. Alphey, 2003. Ectopic expression of inhibitors of protein phosphatase type 1 (PP1) can be used to analyze roles of PP1 in Drosophila development. Genetics 165: 235–245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett, D., E. Lyulcheva and L. Alphey, 2006. Towards a comprehensive analysis of the protein phosphatase 1 interactome in Drosophila. J. Mol. Biol. 364: 196–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berndt, N., M. Dohadwala and C. W. Liu, 1997. Constitutively active protein phosphatase 1alpha causes Rb-dependent G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Curr. Biol. 7: 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen, M., 2001. Combinatorial control of protein phosphatase-1. Trends Biochem. Sci. 26: 426–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand, A. H., and N. Perrimon, 1993. Targeted gene expression as a means of altering cell fates and generating dominant phenotypes. Development 118: 401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceulemans, H., and M. Bollen, 2004. Functional diversity of protein phosphatase-1, a cellular economizer and reset button. Physiol. Rev. 84: 1–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clyne, P. J., S. J. Certel, M. de Bruyne, L. Zaslavsky, W. A. Johnson et al., 1999. The odor specificities of a subset of olfactory receptor neurons are governed by Acj6, a POU-domain transcription factor. Neuron 22: 203–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, P. T. W., 2002. Protein phosphatase 1—targeted in many directions. J. Cell Sci. 115: 241–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrádi, V., and P. T. W. Cohen, 1992. Protein phosphorylation is involved in the regulation of chromatin condensation during interphase. FEBS Lett. 312: 21–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrádi, V., J. M. Axton, H. M. Barker and P. T. Cohen, 1990. Protein phosphatase 1 activity in Drosophila mutants with abnormalities in mitosis and chromosome condensation. FEBS Lett. 275: 39–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dombrádi, V., D. J. Mann, R. D. C. Saunders and P. T. W. Cohen, 1993. Cloning of the fourth functional gene for protein phosphatase 1 in Drosophila melanogaster from its chromosomal location. Eur. J. Biochem. 212: 177–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egloff, M. P., D. F. Johnson, G. Moorhead, P. T. Cohen, P. Cohen et al., 1997. Structural basis for the recognition of regulatory subunits by the catalytic subunit of protein phosphatase 1. EMBO J. 16: 1876–1887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Delgado, G., C. W. Liu, R. Sposto and N. Berndt, 2007 A limited screen for protein interactions reveals new roles for protein phosphatase 1 in cell cycle control and apoptosis. J. Proteome Res. 6(3): 1165–1175. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Hartshorne, D. J., 1998. Myosin phosphatase: subunits and interactions. Acta Physiol. Scand. 164: 483–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hormi-Carver, K.-K., W. Shi, C. W. Y. Liu and N. Berndt, 2004. Protein phosphatase 1alpha is required for murine lung growth and morphogenesis. Dev. Dyn. 229: 797–801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii, K., K. Kumada, T. Toda and M. Yanagida, 1996. Requirement for PP1 phosphatase and 20S cyclosome/APC for the onset of anaphase is lessened by the dosage increase of a novel gene sds23+. EMBO J. 15: 6629–6640. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kellerman, K. A., and K. G. Miller, 1992. An unconventional myosin heavy chain gene from Drosophila melanogaster. J. Cell Biol. 119: 823–834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laski, F. A., D. C. Rio and G. M. Rubin, 1986. Tissue specificity of Drosophila P element transposition is regulated at the level of mRNA splicing. Cell 44: 7–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, B., M. Beullens, H. Ceulemans, B. Himpens and M. Bollen, 2005. Determinants of the nucleolar targeting of protein phosphatase-1. FEBS Lett. 579: 5626–5630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Q., E. S. Buckler, S. V. Muse and J. C. Walker, 1999. Molecular evolution of type 1 serine/threonine protein phosphatases. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 12: 57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan, L. B., M. A. Bass, N. Cheng, E. F. Howard, M. Tamura et al., 1999. Brain actin-associated protein phosphatase 1 holoenzymes containing spinophilin, neurabin, and selected catalytic subunit isoforms. J. Biol. Chem. 274: 35845–35854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, T., M. Amano, K. Kaibuchi and Y. Nishida, 1999. Identification and characterization of Drosophila homolog of Rho-kinase. Gene 238: 437–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Printen, J. A., M. J. Brady and A. R. Saltiel, 1997. PTG, a protein phosphatase 1-binding protein with a role in glycogen metabolism. Science 275: 1475–1478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan, S., I. Williams, H. Aslam, D. Thomas, B. Szoor et al., 2000. Protein phosphatase 1beta is required for the maintenance of muscle attachments. Curr. Biol. 10: 269–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritisch and T. M. Maniatis, 1989. Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Terrak, M., F. Kerff, K. Langsetmo, T. Tao and R. Dominguez, 2004. Structural basis of protein phosphatase 1 regulation. Nature 429: 780–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry-Lorenzo, R. T., L. C. Carmody, J. W. Voltz, J. H. Connor, S. Li et al., 2002. The neuronal actin-binding proteins, neurabin I and neurabin II, recruit specific isoforms of protein phosphatase-1 catalytic subunits. J. Biol. Chem. 277: 27716–27724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toba, G., T. Ohsako, N. Miyata, T. Ohtsuka, K. H. Seong et al., 1999. The gene search system: a method for efficient detection and rapid molecular identification of genes in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 151: 725–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkle-Mulcahy, L., J. E. Sleeman and A. I. Lamond, 2001. Dynamic targeting of protein phosphatase 1 within the nuclei of living mammalian cells. J. Cell Sci. 114: 4219–4228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinkle-Mulcahy, L., P. D. Andrews, S. Wickramasinghe, J. Sleeman, A. Prescott et al., 2003. Time-lapse imaging reveals dynamic relocalisation of PP1gamma throughout the mammalian cell cycle. Mol. Biol. Cell 14: 107–117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varmuza, S., A. Jurisicova, K. Okano, K. Boekelheide and E. B. Shipp, 1999. Spermiogenesis is impaired in mice bearing a targeted mutation in protein phosphatase 1cgamma gene. Dev. Biol. 205: 98–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vereshchagina, N., D. Bennett, B. Szoor, J. Kirchner, S. Gross et al., 2004. The essential role of PP1beta in Drosophila is to regulate non-muscle myosin. Mol. Biol. Cell 15: 4395–4405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wustmann, G., J. Szidonya, H. Taubert and G. Reuter, 1989. The genetics of position-effect variegation modifying loci in Drosophila melanogaster. Mol. Gen. Genet. 217: 520–527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yong, J., I. Tan, L. Lim and T. Leung, 2006. Phosphorylation of myosin phosphatase targeting subunit 3 (MYPT3) and regulation of protein phosphatase 1 by protein kinase A. J. Biol. Chem. 281: 31202–31211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]