Abstract

From biological and genetic standpoints, centromeres play an important role in the delivery of the chromosome complement to the daughter cells at cell division. The positions of the centromeres of potato were determined by half-tetrad analysis in a 4x–2x population where the male parent produced 2n pollen by first-division restitution (FDR). The genetic linkage groups and locations of 95 male parent-derived amplified fragment length polymorphism markers could be determined by comparing their position on a 2x–2x highly saturated linkage map of potato. Ten centromere positions were identified by 100% heterozygosity transmitted from the 2n heterozygous gametes of the paternal parent into the tetraploid offspring. The position of these centromeric marker loci was in accordance with those predicted by the saturated 2x–2x map using the level of marker clustering as a criterion. Two remaining centromere positions could be determined by extrapolation. The frequent observation of transmission of 100% heterozygosity proves that the meiotic restitution mechanism is exclusively based on FDR. Additional investigations on the position of recombination events of three chromosomes with sufficient numbers of markers showed that only one crossover occurred per chromosome arm, proving strong interference of recombination between centromere and telomere.

THE centromere is a specialized domain in most eukaryotic chromosomes that ensures delivery of one copy of each chromosome to each daughter cell during cell division by the mechanisms of kinetochore nucleation, spindle attachment, and sister chromatid cohesion. When these processes fail, the daughter cells will have unbalanced chromosome numbers, which can result in reduced vigor or fertility and, in some cases, lethality (Copenhaver and Preuss 1999; Copenhaver et al. 1999; Cleveland et al. 2003; Hall et al. 2004). In Arabidopsis their structure is composed of moderately repetitive DNA and a core of 180-bp repeats embedded in a highly methylated and repetitive pericentromeric region (Hall et al. 2004).

In Arabidopsis thaliana the position of the centromeres could be mapped by controlled pollinations with four pollen grains that have remained attached due to the quartet (qrt) mutation. These quartets of four pollen grains descend from the four cells that result from a meiotic division. The genotypes of the four offspring plants can be explored with molecular marker loci. The allele combinations in the offspring are indicated as parental ditype or nonparental ditype and can be expected when loci are close to the centromere. Allele combinations indicated as tetratype result from a recombination event between the marker loci and/or the centromere (Copenhaver et al. 2000). Centromere mapping via tetrad analysis can be performed in a limited number of plant species that keep their meiotic products together in tetrads, such as water lilies (Nymphaea), cattails (Typhaceae), heath (Ericaceae and Epacridceae), evening primroses (Onagraceae), sundews (Droseraceae), orchids (Orchidaceae), acacias (Mimosaceae), Dysoxylum spp. (Meliaceae), and Petunia (Solanaceae) (reviewed by Copenhaver et al. 2000).

In many more organisms the centromeres can be localized with half-tetrad analysis (HTA). HTA is an approach comparable to tetrad analysis although based on only two chromatids from a single meiosis. These two chromatids remain together due to omission of the first or the second meiotic division, resulting in numerically unreduced or 2n gametes. Unreduced gametes have been described in insects and fish (e.g. Baldwin and Chovnick 1967; Lindner et al. 2000, respectively). Among plants, in general, diploid species produce haploid (n) gametes, but unreduced (2n) gametes have been observed in many plant species (Harlan and de Wet 1975), including genetically well-studied crop species such as alfalfa (Tavoletti et al. 1996), maize (Rhoades and Dempsey 1966), and potato (Mendiburu and Peloquin 1979). Likewise, 2n gametes commonly occur in Solanum species (Carputo et al. 2000).

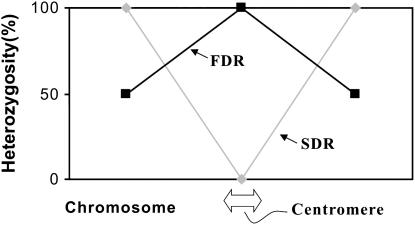

In diploid potato several meiotic restitution mechanisms that lead to 2n gamete formation have been reported (reviewed by Veilleux 1985; Ramanna and Jacobsen 2003). First-division restitution (FDR) and second-division restitution (SDR) have been considered as the two basic types of them (Mok and Peloquin 1975; Ramanna 1979). In the absence of crossover in the meiocyte, all parental heterozygous loci will be heterozygous in FDR gametes. In those cases of FDR where crossovers occur, the loci from centromere to the first crossover point will remain heterozygous. On the contrary, in the case of SDR all the loci that are situated between the centromere and the first crossover will be homozygous in the 2n gametes. However, a single crossover between a locus and the centromere will produce 50% heterozygous and 50% homozygous gametes in FDR, but all these loci will be heterozygous in SDR gametes (Lindner et al. 2000). Therefore, the percentage of heterozygosity or homozygosity of the 2n gametes can be used to estimate the genetic distance between marker and centromere (Figure 1).

Figure 1.—

Probability of heterozygosity. This depends on the FDR or SDR mechanism of unreduced gamete formation and on the position of the centromere on the chromosome.

If 2n gametes are produced by FDR and when transmission of heterozygosity at a locus increases to 100%, the locus is closer to the centromere, but if it decreases to 50%, the locus is closer to the telomere. In SDR, if the heterozygosity of a locus is 0%, the locus is located on the centromere but if it is 100%, the locus is on the telomere.

In potato, the positions of centromeres were putatively proposed by the observation of strong clustering of markers in an ultrahigh dense (UHD) genetic map of potato comprising >10,000 amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers (van Os et al. 2006). The observation of clusters with several hundreds of cosegregating markers suggested a dramatically reduced level of meiotic recombination where physical to genetic distances may range up to 40 Mbp/cM. The observation that AFLP markers tend to be clustered in centromeric regions has been observed in several species and indicates recombination suppression (Keim et al. 1997; Alonso-Blanco et al. 1998; Qi et al. 1998). The aim of this research was to identify and localize the genetic positions of centromeres using HTA in the 4x–2x cross population and to compare them with those identified by marker density in the UHD map.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant materials:

A tetraploid (2n = 4x = 48) mapping population RH4X-103 consisting of 233 genotypes was used. This population was created from a cross between tetraploid 707TG11-1 and diploid RH89-039-16 (2n = 2x = 24). The male parent RH89-039-16 can be crossed with tetraploid female parents because of the production of 2n pollen. More commonly, clone RH89-039-16 is crossed with other diploids to generate diploid mapping populations (Rouppe van der Voort et al. 1997, 1998, 2000; Park et al. 2005), including the population that was used to generate the UHD map in potato (Isidore et al. 2003; van Os et al. 2006). In the UHD map, the genetic position of >10,000 AFLP markers has been determined (http://potatodbase.dpw.wau.nl/UHDdata.html). Images of these primer combinations are available at http://www.dpw.wageningen-ur.nl/uhd/.

DNA isolation:

DNA isolation was performed as described by van der Beek et al. (1992). Fresh leaf tissue was ground using a Retsch machine (Retsch, Haan, Germany) with two steel balls in 96-well Coster plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). After incubation of the Coster plates at 65° in a water bath for 1 hr, ice-cold chloroform isoamyl alcohol (24:1) was added. After centrifugation, the supernatant was transferred to new tubes followed by addition of 1 vol of isopropanol. A further centrifugation step was used to precipitate DNA. After drying, the DNA pellet was dissolved in T0.1E-buffer (+ 0.5 μg RNAse).

AFLP marker analysis:

To generate AFLP markers (Vos et al. 1995), primary templates were prepared by using two different restriction enzyme combinations, EcoRI/MseI and PstI/MseI. After digestion of DNA with the enzymes, adaptors fitting to the EcoRI, PstI, and MseI sites were ligated to each end. The primary templates were diluted prior to the selective preamplification. The first PCR amplification of the adaptor-ligated restriction fragments (primary templates) was accomplished with single-nucleotide extended primers to decrease the number of restriction fragments. The preamplified products (secondary templates) were checked on a 1% agarose gel. After 10× dilution, the secondary templates were suitable for AFLP reactions with selective primers. For the selective amplification, radioactively labeled (33P) E + 3 and P + 2 primers were used in combination with M + 3 primers. The 33P-labeled PCR products were loaded on the gel after 30 min of prerun. The amplified DNA fragments were separated for 2.5 hr on a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 1× TBE buffer. The gels were dried on Whatmann papers for 2 hr in a vacuum and X-ray films were exposed for 4–6 days.

AFLP marker patterns, generated from 23 E + 3/M + 3 and 5 P + 2/M + 3 primer combinations, were analyzed on the basis of the presence or absence of a band, but also zygosity was recorded on the basis of band intensities. Only heterozygous AFLP markers from the diploid male parent were used when they were absent in the 4x female parent (aaaa × ab). The offspring genotypes were scored as “aa,” “ab,” “bb,” and “uu,” indicating the transmission of homozygous aa or bb gametes, that of heterozygous ab gametes, or unknown. The simplex (aaab) and duplex (aabb) tetraploid offspring genotypes could be distinguished visually on the basis of band intensity. For each marker the frequency of the genotype classes was calculated and the locus–centromere distance could be estimated using the formula D = [f(duplex) + f(nulliplex)] × 100 cM, where f is the frequency of the offspring genotype classes (Douches and Quiros 1987). The genetic position of individual AFLP loci within a linkage group and a chromosome arm was compared with the position of the marker in the UHD map. Identical AFLP markers can be recognized by their mobility on the gel, which is also reflected by the name of the marker. Marker names are based on the two restriction enzymes used, the three or two selective nucleotides, and the mobility of the fragment relative to the 10-bp ladder (Sequamark; Research Genetics, Huntsville, AL). MapChart (Voorrips 2002) was used to draw and to compare the linkage maps constructed in this study with those of the UHD map.

RESULTS

AFLP marker scoring:

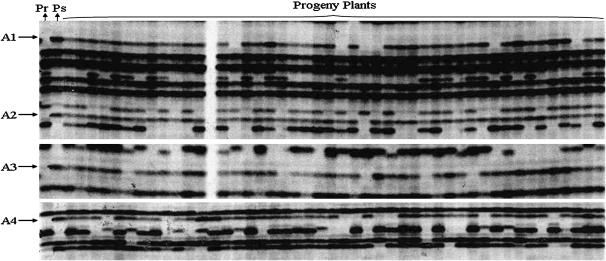

AFLP markers for centromere mapping were generated with 28 EcoRI/MseI and PstI/MseI primer combinations. The number of suitable nulliplex × heterozygous (aaaa × ab) markers varied between 1 and 11, with an average of 4.3 markers per primer combination. A total of 130 markers, derived from the diploid male parent RH89-039-16, were obtained. An image of a part of three AFLP gels is shown in Figure 2, showing four scorable segregating markers derived from the diploid male parent (A1–A4). For markers A1 and A2 six and one nulliplex offspring genotypes can be observed, indicating that the A2 marker is closer to the centromere.

Figure 2.—

An image of AFLP gels containing segregating markers produced by FDR. Four AFLP markers, A1, A2, A3, and A4 are shown. The first lane, “Pr,” is the tetraploid female parent “707TG11-1” and the second lane, “Ps,” is the diploid male parent “RH89-039-16” that produced unreduced gametes. All other lanes are tetraploid progeny plants.

Genetic map and centromere mapping:

Markers cannot be grouped into linkage groups by conventional methods because all centromeric markers display the uniform nulliplex genotype (aaab). Therefore, AFLP fingerprints from this cross were compared with fingerprints of the UHD map to identify segregating paternal markers from the clone RH89-039-16 in this tetraploid mapping population and segregating paternal markers that were in common with the UHD map. From the total of 130 markers a subset of 95 markers was segregating in both populations. The location of these 95 markers was obtained from the online database http://potatodbase.dpw.wau.nl/UHDdata.html, using the mobility of the marker combined with a 10-bp ladder (Sequamark, Research Genetics). According to their location in the UHD map, the markers were grouped into linkage groups and arranged according to their genetic position within each linkage group. For 78 markers the genetic position information was highly accurate because the marker segregated in a 1:1 ratio in the map of RH89-039-16. For 17 markers the position could range across a small interval. These 17 markers were heterozygous in both parents of the diploid map and the mapping of a 3:1 segregating marker cannot be as accurate as that of the 1:1 markers. In Table 1, the segregation ratios and the frequencies of the different alleles are presented. On the basis of these observations the position relative to the centromere is presented, both in observed percentage of heterozygosity and in the calculated distances (in centimorgans).

TABLE 1.

Segregation of AFLP markers on the 12 chromosomes of potato and determination of the genetic position of the centromeres

| Allele segregation

|

Map position

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AFLP loci | aa(f)a | ab(f) | bb(f) | Heterozygosity | [f(a) + f(b)] × 100b | Chromosome and binc |

| EACTMCAA_197 | 16(0.09) | 158(0.90) | 1(0.01) | 0.903 | 9.7 | RH01 (H × H)d |

| EACAMCCT_90 | 1(0.00) | 222(0.96) | 8(0.03) | 0.961 | 3.9 | RH01B10 |

| EACTMCTC_217.1 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B12 |

| EAACMCAG_261.4 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EAACMCAG_196.4 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EAACMCAG_143.6 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EAACMCAG_139.9 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EAACMCCA_189.0 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EAACMCCA_136.8 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EAACMCCT_82.7 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACAMCAA_203.2 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACAMCAA_142.1 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACTMCAG_127.1 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACTMCAG_65.0 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACTMCTC_196.8 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACTMCTC_219.5 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH01B13 |

| EACTMCAA_207 | 1(0.00) | 230(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 0.996 | 0.4 | RH01B13 |

| EACAMCCT_145 | 33(0.14) | 177(0.77) | 19(0.08) | 0.773 | 22.7 | RH01B36 |

| EACTMCAA_287 | 6(0.03) | 208(0.96) | 2(0.01) | 0.963 | 3.7 | RH02 (H × H) |

| EACTMCAA_134.5 | 0(0.00) | 139(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH02B01 |

| EACAMCAA_466 | 6(0.03) | 219(0.96) | 4(0.02) | 0.956 | 4.4 | RH02B02 |

| PACMAAC_269 | 7(0.03) | 218(0.94) | 6(0.03) | 0.944 | 5.6 | RH02B02 |

| EACTMCAG_81 | 31(0.13) | 177(0.77) | 22(0.10) | 0.770 | 23.0 | RH02B24 |

| EAACMCCT_140.3 | 39(0.17) | 163(0.71) | 27(0.12) | 0.712 | 28.8 | RH02B29 |

| PACMAAC_279 | 35(0.16) | 145(0.63) | 51(0.22) | 0.628 | 37.2 | RH02B35 |

| PCGMAGA_234 | 45(0.19) | 119(0.51) | 69(0.30) | 0.511 | 48.9 | RH02B53 |

| EACTMCAG_128 | 43(0.20) | 151(0.70) | 22(0.10) | 0.699 | 30.1 | RH03 (H × H) |

| PCGMAGA_249 | 5(0.02) | 209(0.90) | 17(0.07) | 0.905 | 9.5 | RH03B30 |

| EACAMCCT_588 | 7(0.03) | 216(0.94) | 7(0.03) | 0.939 | 6.1 | RH03B32 |

| EAGAMCTA_133.1 | 1(0.01) | 108(0.99) | 0(0.00) | 0.991 | 0.9 | RH03B37 |

| EAGAMCAT_246.6 | 9(0.08) | 96(0.89) | 3(0.03) | 0.889 | 11.1 | RH03B37 |

| PCGMAGA_175 | 8(0.04) | 206(0.90) | 14(0.06) | 0.904 | 9.6 | RH04B15 |

| EAACMCGA_322 | 9(0.04) | 213(0.92) | 10(0.04) | 0.918 | 8.2 | RH04B20 |

| EAGTMCAG_130 | 5(0.02) | 217(0.94) | 9(0.04) | 0.939 | 6.1 | RH04B20 |

| PACMAAT_146 | 7(0.03) | 220(0.94) | 6(0.03) | 0.944 | 5.6 | RH04B22 |

| EAACMCTG_234 | 2(0.01) | 225(0.98) | 3(0.01) | 0.978 | 2.2 | RH04B25 |

| EACAMCAC_72 | 3(0.01) | 228(0.99) | 0(0.00) | 0.987 | 1.3 | RH04B25 |

| EACAMCAA_244.5 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH04B35 |

| EACAMCCT_492.8 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH04B35 |

| EAACMCGA_256.6 | 42(0.19) | 175(0.77) | 9(0.04) | 0.774 | 22.6 | RH04B73 |

| PACMAAT_314 | 2(0.01) | 228(0.99) | 1(0.00) | 0.987 | 1.3 | RH05 (H × H) |

| PACMAAT_98 | 28(0.12) | 187(0.81) | 17(0.07) | 0.806 | 19.4 | RH05B02 |

| EATGMCAC_181.8 | 37(0.17) | 160(0.73) | 22(0.10) | 0.731 | 26.9 | RH05B03 |

| EACAMCAC_317.0 | 7(0.03) | 220(0.97) | 0(0.00) | 0.969 | 3.1 | RH05B43 |

| EACTMCAA_366.0 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH05B44 |

| EAACMCAG_231.8 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH05B46 |

| EAACMCAG_135.2 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH05B46 |

| EAACMCCA_410.3 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH05B46 |

| EATGMCAC_137 | 5(0.02) | 208(0.96) | 4(0.02) | 0.959 | 4.1 | RH06B01 |

| PATMAGA_335 | 2(0.01) | 224(0.97) | 4(0.02) | 0.974 | 2.6 | RH06B03 |

| EAACMCCT_377.0 | 1(0.00) | 226(0.99) | 2(0.01) | 0.987 | 1.3 | RH06B15 |

| EAACMCCA_231.3 | 3(0.01) | 228(0.99) | 0(0.00) | 0.987 | 1.3 | RH06B16 |

| EAACMCGA_535.5 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH06B17 |

| EACAMCAC_553.6 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH06B17 |

| EACTMCAG_365.4 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH06B17 |

| EATGMCAC_185 | 13(0.06) | 205(0.92) | 4(0.02) | 0.923 | 7.7 | RH06B19 |

| EATGMCAC_187 | 13(0.06) | 205(0.92) | 4(0.02) | 0.923 | 7.7 | RH06B19 |

| EAACMCTG_153 | 25(0.11) | 167(0.73) | 38(0.17) | 0.726 | 27.4 | RH06B28 |

| EACAMCAC_90 | 28(0.12) | 159(0.69) | 44(0.19) | 0.688 | 31.2 | RH06B31 |

| EAACMCCT_144.2 | 45(0.20) | 138(0.60) | 46(0.20) | 0.603 | 39.7 | RH06B50 |

| EAACMCCA_112 | 15(0.06) | 194(0.84) | 22(0.10) | 0.840 | 16.0 | RH07 (H × H) |

| EACAMCCT_529 | 1(0.00) | 227(0.98) | 3(0.01) | 0.983 | 1.7 | RH07 (H × H) |

| EACTMCAG_293 | 40(0.17) | 136(0.59) | 54(0.23) | 0.591 | 40.9 | RH07 (H × H) |

| EACAMCAA_386 | 55(0.24) | 155(0.67) | 21(0.09) | 0.671 | 32.9 | RH07B34 |

| EAACMCAA_188.5 | 0(0.00) | 93(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH07B68 |

| EAACMCGA_70.5 | 10(0.04) | 223(0.96) | 0(0.00) | 0.957 | 4.3 | RH07B77 |

| PACMAAT_413 | 24(0.10) | 194(0.85) | 11(0.05) | 0.847 | 15.3 | RH08 (H × H) |

| EATGMCAG_262 | 39(0.17) | 156(0.68) | 34(0.15) | 0.681 | 31.9 | RH08B09 |

| EAACMCCA_437.7 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH08B22 |

| EAACMCCA_141.0 | 2(0.01) | 228(0.98) | 3(0.01) | 0.790 | 2.1 | RH08B26 |

| EATGMCAC_278 | 8(0.04) | 207(0.94) | 6(0.03) | 0.937 | 6.3 | RH08B34 |

| EAACMCAG_130 | 16(0.07) | 155(0.67) | 62(0.27) | 0.665 | 33.5 | RH09 (H × H) |

| EACAMCAA_125 | 38(0.17) | 140(0.62) | 49(0.22) | 0.617 | 38.3 | RH09 (H × H) |

| EACTMCAG_546 | 39(0.17) | 138(060) | 53(0.23) | 0.600 | 40.0 | RH09 (H × H) |

| EACAMCAA_158 | 18(0.08) | 194(0.85) | 16(0.07) | 0.851 | 14.9 | RH09B03 |

| EACTMCTC_228.6 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH09B31 |

| PACMAAT_76 | 11(0.05) | 216(0.93) | 5(0.02) | 0.931 | 6.9 | RH09B37 |

| EAACMCTG_89 | 27(0.12) | 172(0.75) | 31(0.13) | 0.748 | 25.2 | RH09B60 |

| EAACMCAG_167.8 | 34(0.15) | 160(0.69) | 39(0.17) | 0.687 | 31.3 | RH09B60 |

| EAACMCCA_222 | 23(0.10) | 187(0.81) | 21(0.09) | 0.810 | 19.0 | RH10 (H × H) |

| PACMAAT_140 | 21(0.09) | 196(0.84) | 16(0.07) | 0.841 | 15.9 | RH10 (H × H) |

| EACAMCAA_230 | 39(0.17) | 157(0.68) | 35(0.15) | 0.680 | 32.0 | RH10B19 |

| EATGMCAC_199 | 13(0.06) | 204(0.92) | 4(0.02) | 0.923 | 7.7 | RH10B56 |

| EATGMCAG_140.3 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH10B64 |

| EACAMCGT_163 | 20(0.09) | 189(0.83) | 20(0.09) | 0.825 | 17.5 | RH11 (H × H) |

| EACAMCGT_161 | 20(0.09) | 189(0.83) | 20(0.09) | 0.825 | 17.5 | RH11 (H × H) |

| EACTMCAG_190 | 2(0.01) | 227(0.98) | 2(0.01) | 0.983 | 1.7 | RH11 (H × H) |

| EACTMCAA_194 | 39(0.22) | 129(0.72) | 10(0.06) | 0.725 | 27.5 | RH11B01 |

| EACTMCAA_190 | 31(0.17) | 131(0.72) | 19(0.10) | 0.724 | 27.6 | RH11B01 |

| EACAMCAC_162 | 13(0.06) | 199(0.86) | 19(0.08) | 0.861 | 13.9 | RH11B17 |

| EACTMCAG_203 | 5(0.02) | 207(0.90) | 18(0.08) | 0.900 | 10.0 | RH11B21 |

| EAGAMCCT_132.3 | 4(0.04) | 103(0.94) | 2(0.02) | 0.945 | 5.5 | RH11B61 |

| EACAMCAC_131 | 19(0.08) | 180(0.78) | 32(0.14) | 0.779 | 22.1 | RH12 (H × H) |

| PACMAAT_306 | 32(0.14) | 190(0.82) | 9(0.04) | 0.823 | 17.7 | RH12B06 |

| EAACMCCT_231.1 | 0(0.00) | 233(1.00) | 0(0.00) | 1.000 | 0.0 | RH12B49 |

“f” indicates allele frequency.

Map distance is calculated using the frequency of homozygosity × 100 cM genetic distance of each chromosome, indicating genetic distance from the centromere.

Chromosome and bin are indicated. For instance, RH01B10 means the marker belongs to bin 10 in chromosome 1 of RH.

H × H means that the marker is derived from both parents SH and RH in the UHD map.

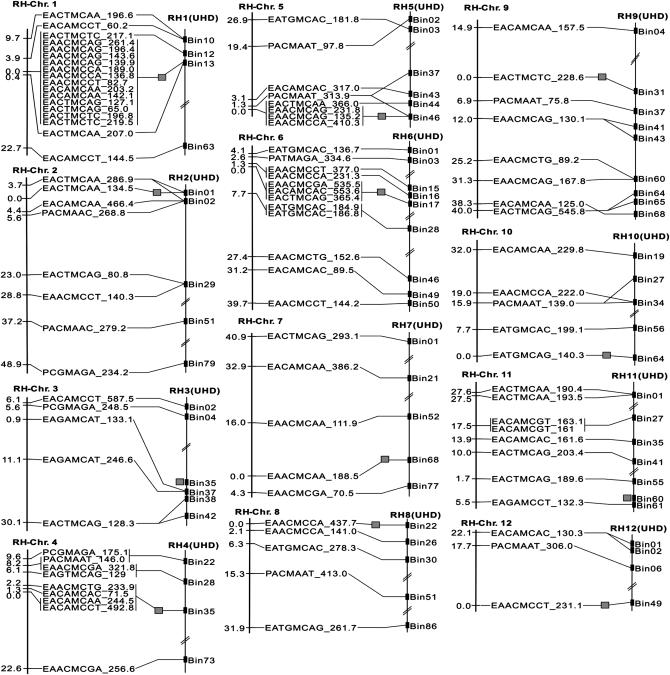

The estimated marker–centromere distances in combination with the position of the markers as taken from the UHD map allowed identification of the positions of centromeres of the 4x–2x male parent map. These results are given in Figure 3. The 4x–2x linkage groups with marker–centromere distances are aligned with the diploid UHD map, showing the positions of the same marker loci except for one on chromosome 5. In addition, the putative centromeric position is indicated by a shaded square in between the tetraploid and the diploid map. These expected centromeric regions were good candidates for positioning the centromeres on each chromosome. For 10 chromosomes, they were located in bin nos. 13, 1, 35, 46, 17, 68, 22, 31, 64, and 49 on chromosome 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 12, respectively. Most of the AFLP markers that belonged to those bins showed 100% heterozygosity although exceptions were found. For example, on chromosome 1, one AFLP marker (EACTMCAA_207) that belonged to bin 13, where the UHD map-based centromere is expected to be located, showed 99.6% heterozygosity, while another AFLP marker (EACTMCTC_217.1) showing 100% heterozygosity belonged to bin 12 instead of bin 13. Similarly one AFLP marker (EACTMCAA_366.0) on chromosome 5 with 100% heterozygosity was located in bin 44 instead of bin 46 where the other 100% heterozygosity markers were located on this chromosome. However, the position of centromeres of these two chromosomes remained in bins 13 and 46, respectively, because more markers with 100% heterozygosity were present in those bins. The accurate positions of centromeres on chromosomes 3 and 11 could not be precisely assigned by the 4x–2x male parent approach because there were no markers showing 100% heterozygosity. However, they could be assigned to the most probable location according to the increasing or decreasing rate of heterozygosity in the 4x–2x map and on the basis of marker density in the UHD map (Figure 3). On chromosome 3, the centromere appeared most probably to be positioned in bin 35 and on chromosome 11 in bin 60. Chromosomes 2 and 12 showed a predominantly terminal location of the centromere that indicates they are telocentric. The positions of all remaining centromeres were metacentric to varying degrees.

Figure 3.—

Comparison of two genetic maps of the male parent RH89-039-16. The two maps were obtained from the 4x–2x cross population (RH-Chr.) and the UHD mapping population (RH-UHD). The two maps of each chromosome have been connected to each other by joint markers. The position of the centromeres of each chromosome is indicated by small shaded boxes between the two maps.

Dissection of three chromosomes:

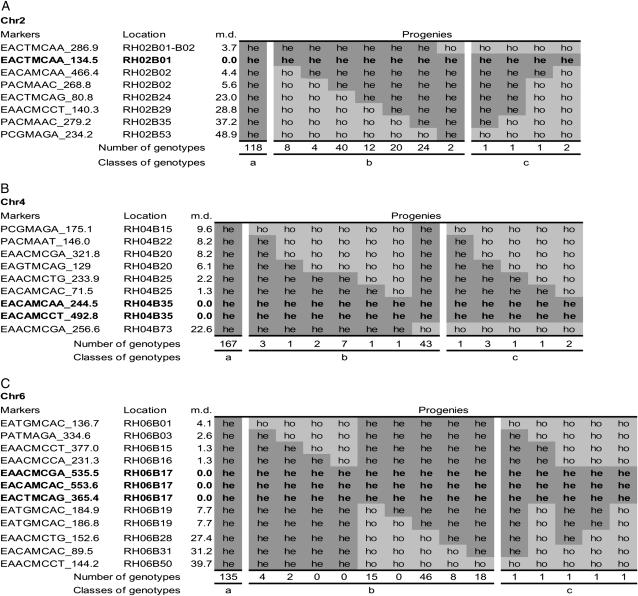

To investigate the assumption that only one crossover occurs per chromosome arm, genetic marker data of 233 genotypes of three chromosomes (chromosomes 2, 4, and 6) were arranged by marker order in a spreadsheet (Figure 4). These three chromosomes had enough markers to analyze one arm of the telocentric chromosome 2 and the metacentric chromosome 4 and both arms of the metacentric chromosome 6. One, two, and three markers on chromosomes 2, 4, and 6, respectively, which were located in the centromeric regions, were all heterozygous, indicating that 2n pollen originated through FDR, but not through a SDR mechanism or a mixture of both. On the telocentric chromosome 2, there was as expected no marker localized on the north arm. On the south arm of chromosome 2, no crossovers were observed in 118 genotypes (group a in Figure 4A) and only one crossover was observed in 110 genotypes (group b in Figure 4A). On the metacentric chromosomes 4 and 6, crossover did not occur in 167 and 135 genotypes (group a in Figure 4, B and C), a single crossover was observed on one of the chromosome arms in 58 and 93 genotypes (group b in Figure 4, B and C), and 8 and 5 genotypes were found with two crossovers per chromosome, but with only one crossover per chromosome arm (group c in Figure 4, B and C), respectively.

Figure 4.—

Marker distribution and graphical genotyping on three chromosomes: chromosomes 2 (A), 4 (B), and 6 (C). Heterozygous (he) and homozygous (ho) markers were formatted by different shading intensity. Regions in boldface type are centromeric regions where all markers are heterozygous. The location indicated is adopted from the UHD map and m.d. is the map distance from the markers to the centromeric region, indicating the frequency of homozygosity. Progenies are classified by the graphical genotypes and number of crossovers. In groups a, b, and c, no crossover, one crossover, and two crossovers occur, respectively.

The frequency of noncrossover for the telocentric chromosome 2 was 118 of 233 and that for the metacentric chromosomes 4 and 6, 167 and 135, respectively. This could be taken as an indication that a telocentric chromosome could show more crossover than a metacentric chromosome. However, testing of the hypothesis that there is no difference in crossover frequency using the χ2-test did not show a significant difference for noncrossover in the three chromosomes 2, 4, and 6 (data not shown), indicating that the crossover frequency for these chromosomes was essentially the same. In addition to this, we could investigate chiasma interference by comparing the expected and the observed distribution of recombination events on the three chromosomes. A Poisson distribution with λ = 0.4235 was estimated on the basis of 296 recombination events distributed over 699 (233 × 3) chromatids, resulting in expected amounts of 458, 194, 41, and 6 chromatids with 0, 1, 2, and 3 recombination events, respectively. Strong overrepresentation in the single-crossover chromatids and underrepresentation in the zero- and multiple-crossover chromatids were observed.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we addressed our research to two main issues. The first was the localization of centromeres on 12 potato chromosomes and the second was the proof of a single crossover per chromosome arm. Previously these two issues for potato chromosome were reported in a few articles (Mendiburu and Peloquin 1979; Douches and Quiros 1987; Bastiaanssen et al. 1996; Bastiaanssen 1997; Chani et al. 2002). However, they were theoretically proposed or the numbers of loci or chromosomes were limited.

Recently the centromere positions of 12 potato chromosomes on the map of the RH parent could tentatively be determined by using marker density as indicator in the UHD map (van Os et al. 2006). They observed that AFLP markers in the UHD map were not evenly distributed over the genetic map. Several centromeric bins contained high numbers of cosegregating markers, while other regions of the map contained much higher numbers of recombination events with much less cosegregating markers per bin. It has been reported that suppression of recombination at a centromere could be 10- to 40-fold higher than that along the rest of a chromosome (Tanksley et al. 1992; Centola and Carbon 1994). The bins, which were densest in each chromosome and, therefore, candidates for centromeric positions were indicated in the UHD map (van Os et al. 2006). They were the same as those obtained from the present study where the centromere position on the chromosomes of RH was identified by using HTA in a 4x–2x cross population (Figure 3). In the present study, it was also shown that normally only one crossover occurs per chromosome arm as proposed by van Veen and Hawley (2003) and Hillers and Villeneuve (2003). This confirms the earlier results in which RFLP analysis was used for localizing centromeres using 2x–4x populations in which 2n eggs originated exclusively through SDR (Bastiaanssen 1997). van Veen and Hawley (2003) and Hillers and Villeneuve (2003) suggested that crossover interference could act over large distances along the length of meiotic chromosomes to limit the number of exchanges but the crossover interference signal could not be transmitted through the centromere or the telomere. Also chiasma interference was suggested (Thorgaard et al. 1983; Liu et al. 1992; Sybenga 1996; Bastiaanssen 1997). With much more markers van Os et al. (2006) have observed very few double crossovers, but only in the longest chromosome arms, such as the telocentric chromosome 2. Our observations support both suggestions that the occurrence of a second crossover per chromosome arm is very rare and strong chiasma interference is evident (Figure 4).

The first HTA was performed in attached-X chromosomes in Drosophila (Beadle and Emerson 1935). In the last decades, gene- or genetic marker-related centromere positions, called gene–centromere mapping, have been identified using HTA in some plants (Mendiburu and Peloquin 1979; Douches and Quiros 1987; Wagenvoort and Zimnoch-Guzowska 1992; Lindner et al. 2000), fishes (Liu et al. 1992; Johnson et al. 1996), and animals (Jarrell et al. 1995; Baudry et al. 2004). However, access to several products of the same meiosis is indispensable to map centromeres. The number of species where centromeres can be genetically mapped, therefore, is relatively limited (Baudry et al. 2004). In HTA using progenies created from a 4x–2x cross, the male parent produces 2n pollen resulting in tetraploid, and not triploid, progenies because of the existence of a so-called triploid block (Marks 1966; Peloquin et al. 1989). In potato it has been suggested that because of the type of meiosis SDR 2n egg cells should be predominant under normal synaptic conditions and transfer a high degree of homozygosity to the progeny, whereas the occurrence of FDR 2n eggs is an exception (Jongedijk 1985; Douches and Quiros 1988; Jongedijk et al. 1991; Werner and Peloquin 1991). In contrast, FDR 2n pollen in synaptic diploids should prevail and transfer a high degree of heterozygosity to the progeny, whereas the occurrence of SDR 2n pollen should be excluded (Ramanna 1983; Peloquin et al. 1989; Watanabe and Peloquin 1993). Therefore, FDR was considered as a mechanism to produce unreduced 2n gametes via 2n pollen and tetraploid progeny in a 4x–2x cross of potato. Depending on the percentage of heterozygosity of the gametes at certain AFLP loci, the centromere position of each chromosome could be localized. The position of 100% heterozygous AFLP loci, where heterozygous gametes were transmitted from the male parent to all of its progeny of the population, was determined as the position of the centromere. In this case, all tetraploid progenies had a simplex genotype. In contrast to Conicella et al. (1991), this study confirms the occurrence of only the FDR mechanism in pollen.

The centromere is one of the most important functional elements of eukaryotic chromosomes. It ensures proper cell division and stable transmission of the genetic material (Wang et al. 2000). Elucidating the composition and structure of centromeres can be of use to understand its functional roles, including chromosome segregation, karyotypic stability, and artificial chromosome-based cloning (Wu et al. 2004). Centromeres of higher eukaryotes are composed of densely methylated, recombination suppressed and cytologically constricted DNA. Its region consists of moderately repeated DNA such as transposons, retroelements, and pseudogenes (Houben and Schubert 2003; Hall et al. 2004). Recently, centromeres were sequenced and studied extensively in several plant species including Arabidopsis (Copenhaver et al. 1999; Kumekawa et al. 2000, 2001; Hosouchi et al. 2002) and main crops such as maize (Nagaki et al. 2003; Jin et al. 2004), rice (Wu et al. 2004), and wheat (Kishii et al. 2001), but little sequencing was reported in potato (Stupar et al. 2002; Tek and Jiang 2004). Although centromere functions are highly conserved, the sequences among the centromeres of related species are not homologous (Hall et al. 2004).

Identification of the genetic position of centromeres, which is important for distinguishing chromosome arms, identifying proximal and distal markers or genes, and providing fixed positions in genetic maps (Bastiaanssen et al. 1996), is the first step to understanding the composition and structure of the centromeric region. In this research, we localized centromeres of most chromosomes of potato by HTA and confirmed these positions with those indicated in the UHD map (van Os et al. 2006). This proves that (1) the marker density approach in the UHD map can be used for positioning of centromeres and (2) HTA in potato is a powerful technique for the same purpose. The identification of the accurate genetic position of centromeres described in this article is a good starting point for future research on the construction of physical contigs of centromeric regions as well as for further research in sequencing and analyzing centromeres.

Acknowledgments

We thank Munikote Ramanna and Simon Foster for critical review of the manuscript.

References

- Alonso-Blanco, C., A. J. M. Peters, M. Koornneef, C. Lister, C. Dean et al., 1998. Development of an AFLP based linkage map of Ler, Col and Cvi Arabidopsis thaliana ecotypes and construction of a Ler/Cvi recombinant inbred line population. Plant J. 14: 259–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, M., and A. Chovnick, 1967. Autosomal half-tetrad analysis in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 55: 277–293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bastiaanssen, H. J. M., 1997. Marker assisted elucidation of the origin of 2n-gametes in diploid potato. Ph.D. Thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, The Netherlands.

- Bastiaanssen, H. J. M., M. S. Ramanna, Z. Sawor, A. Mincione, A. v. d. Steen et al., 1996. Pollen markers for gene-centromere mapping in diploid potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 93: 1040–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baudry, E., P. Kryger, M. Allsopp, N. Koeniger, D. Vautrin et al., 2004. Whole-genome scan in thelytokous-laying workers of the cape honeybee (Apis mellifera capensis): central fusion, reduced recombination rates and centromere mapping using half-tetrad anaysis. Genetics 167: 243–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beadle, G., and S. Emerson, 1935. Further studies of crossing-over in attached-X chromosomes of Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 20: 192–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carputo, D., A. Barone and L. Frusciante, 2000. 2n gametes in the potato: essential ingredients for breeding and germplasm transfer. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101: 805–813. [Google Scholar]

- Centola, M., and J. Carbon, 1994. Cloning and characterization of centromeric DNA from Neurospora crassa. Mol. Cell. Biol. 14: 1510–1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chani, E., V. Ashkenazi, J. Hillel and R. E. Veilleux, 2002. Microsatellite marker analysis of an anther-derived potato family: skewed segregation and gene-centromere mapping. Genome 45: 236–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleveland, D. W., Y. Mao and K. F. Sullivan, 2003. Centromeres and kinetochores: from epigenetics to mitotic checkpoint signaling. Cell 112: 407–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conicella, C., A. Barone, A. Del Giudice, L. Frusciante and L. M. Monti, 1991. Cytological evidences of SDR-FDR mixture in the formation of 2n eggs in a potato diploid clone. Theor. Appl. Genet. 81: 59–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver, G. P., and D. Preuss, 1999. Centromeres in the genomic era: unraveling paradoxes. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2: 104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver, G. P., K. Nickel, T. Kuromori, M. Benito, S. Kaul et al., 1999. Genetic definition and sequence analysis of Arabidopsis centromeres. Science 286: 2468–2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copenhaver, G. P., K. C. Keith and D. Preuss, 2000. Tetrad analysis in higher plants. A budding technology. Plant Physiol. 124: 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douches, D. S., and C. F. Quiros, 1987. Use of 4x-2x crosses to determine gene-centromere map distances of isozyme loci in Solanum species. Genome 29: 519–527. [Google Scholar]

- Douches, D. S., and C. F. Quiros, 1988. Genetic strategies to determine the mode of 2n egg formation in diploid potatoes. Euphytica 38: 247–260. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. E., K. C. Keith, S. E. Hall, G. P. Copenhaver and D. Preuss, 2004. The rapidly evolving field of plant centromeres. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 7: 108–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlan, J. R., and J. M. J. de Wet, 1975. On Ö, Winge and a prayer: the origins of polyploidy. Bot. Rev. 41: 361–390. [Google Scholar]

- Hillers, K. J., and A. M. Villeneuve, 2003. Chromosome-wide control of meiotic crossing over in C. elegans. Curr. Biol. 13: 1641–1647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosouchi, T., N. Kumekawa, H. Tsuruoka and H. Kotani, 2002. The size and sequence organization of the centromeric region of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 1, 2 and 3. DNA Res. 9: 117–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houben, A., and I. Schubert, 2003. DNA and proteins of plant centromeres. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 6: 554–560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidore, E., H. van Os, S. Andrzejewski, J. Bakker, I. Barrena et al., 2003. Toward a marker-dense meiotic map of the potato genomes: lessons from linkage group I. Genetics 165: 2107–2116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin, W., J. R. Melo, K. Nagaki, P. B. Talbert, S. Henikoff et al., 2004. Maize centromeres: organization and functional adaptation in the genetic background of oat. Plant Cell 16: 571–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarrell, V. L., H. A. Lewin, Y. Da and M. B. Wheeler, 1995. Gene-centromere mapping of bovine DYA, DRB3, and PRL using secondary oocytes and first polar bodies: evidence for four-strand double crossovers between DYA and DRB3. Genomics 27: 33–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, S. L., M. A. Gates, M. Johnson, W. S. Talbot, S. Horne et al., 1996. Centromere-linkage analysis and consolidation of the zebrafish genetic map. Genetics 142: 1277–1288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jongedijk, E., 1985. The pattern of megasporogenesis and megagametophytes in diploid Solanum species hybrids; its relevance to the origin of 2n-eggs and the induction of apomixes. Euphytica 34: 599–611. [Google Scholar]

- Jongedijk, E., M. S. Ramanna, Z. Sawor and J. G. T. Hermsen, 1991. Formation of first division restitution (FDR) 2n-megaspores through pseudohomotypic division in ds-1 (desynapsis) mutants of diploid potato: routine production of tetraploid progeny from 2xFDR x 2xFDR crosses. Theor. Appl. Genet. 82: 645–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keim, P., J. M. Schupp, S. E. Travis, K. Clayton, T. Zhu et al., 1997. A high-density soybean genetic map based on AFLP markers. Crop Sci. 37: 537–543. [Google Scholar]

- Kishii, M., K. Nagaki and H. Tsujimoto, 2001. A tandem repetitive sequence located in the centromeric region of common wheat (Triticum aestivum) chromosomes. Chromosome Res. 9: 417–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumekawa, N., T. Hosouchi, H. Tsuruoka and H. Kotani, 2000. The size and sequence organization of the centromeric region of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 5. DNA Res. 7: 315–321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumekawa, N., T. Hosouchi, H. Tsuruoka and H. Kotani, 2001. The size and sequence organization of the centromeric region of Arabidopsis thaliana chromosome 4. DNA Res. 8: 285–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindner, K. R., J. E. Seeb, C. Habicht, K. L. Knudsen, E. Kretschmer et al., 2000. Gene-centromere mapping of 312 loci in pink salmon by half-tetrad analysis. Genome 43: 538–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q., C. A. Goudie, B. A. Simco, K. B. Davis and D. C. Morizot, 1992. Gene-centromere mapping of six enzyme loci in gynogenetic Channel Catfish. J. Hered. 83: 245–248. [Google Scholar]

- Marks, G. E., 1966. The origin and significance of intraspecific polyploidy: experimental evidence from Solanum chacoense. Evolution 20: 552–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendiburu, A. O., and S. J. Peloquin, 1979. Gene-centromere mapping by 4x-2x matings in potatoes. Theor. Appl. Genet. 54: 177–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mok, D. W. S., and S. J. Peloquin, 1975. The inheritance of three mechanisms of diplandroid (2n-pollen) formation in diploid potatoes. Heredity 35: 295–302. [Google Scholar]

- Nagaki, K., J. Song, R. M. Stupar, A. S. Parokonny, Q. Yuan et al., 2003. Molecular and cytological analysis of large tracks of centromeric DNA reveal the structure and evolutionary dynamics of maize centromeres. Genetics 163: 759–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park, T.-H., V. G. A. A. Vleeshouwers, R. C. B. Hutten, H. J. van Eck, E. van der Vossen et al., 2005. High-resolution mapping and analysis of the resistance locus Rpi-abpt against Phytophthora infestans in potato. Mol. Breed. 16: 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Peloquin, S. J., G. L. Yerk and J. E. Werner, 1989. Ploidy manipulation in the potato, pp. 167–178 in Chromosomes: Eukaryotic, Prokaryotic, and Viral, Vol. II, edited by K. W. Adolph. CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

- Qi, X., P. Stam and P. Lindhout, 1998. Use of locus-specific AFLP markers to construct a high-density molecular map in barley. Theor. Appl. Genet. 96: 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramanna, M. S., 1979. A re-examination of the mechanisms of 2n gamete formation in potato and its implications for breeding. Euphytica 28: 537–561. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanna, M. S., 1983. First division restitution gametes through fertile desynaptic mutants of potato. Euphytica 32: 337–350. [Google Scholar]

- Ramanna, M. S., and E. Jacobsen, 2003. Relevance of sexual polyploidization for crop improvement—a review. Euphytica 133: 3–18. [Google Scholar]

- Rhoades, M. M., and E. Dempsey, 1966. Induction of chromosome doubling at meiosis by the elongation gene in maize. Genetics 54: 505–522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouppe van der Voort, J., P. Wolters, R. Folkertsma, R. Hutten, P. van Zandvoort et al., 1997. Mapping of the cyst nematode resistance locus Gpa2 in potato using a strategy based on comigrating AFLP markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 95: 874–880. [Google Scholar]

- Rouppe van der Voort, J., W. Lindeman, R. Folkertsma, R. Hutten, H. Overmars et al., 1998. A QTL for broad-spectrum resistance to cyst nematode species (Globodera spp.) maps to a resistance gene cluster in potato. Theor. Appl. Genet. 96: 654–661. [Google Scholar]

- Rouppe van der Voort, J., E. van der Vossen, E. Bakker, H. Overmars, P. van Zandvoort et al., 2000. Two additive QTLs conferring broad-spectrum resistance in potato to Globodera pallida are localized on resistance gene clusters. Theor. Appl. Genet. 101: 1122–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Stupar, R. M., J. Song, A. L. Tek, Z. Cheng, F. Dong et al., 2002. Highly condensed potato pericentromeric heterochromatin contains rDNA-related tandem repeats. Genetics 162: 1435–1444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sybenga, J., 1996. Recombination and chiasmata; few but intriguing discrepancies. Genome 39: 473–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanksley, S. D., M. W. Ganal, J. P. Prince, M. C. De Vicente, M. W. Bonierbale et al., 1992. High density molecular linkage maps of the tomato and potato genomes. Genetics 132: 1141–1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavoletti, S., E. T. Bingham, B. S. Yandell, F. Veronesi and T. C. Osborn, 1996. Half tetrad analysis in alfalfa using multiple restriction fragment length polymorphism markers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93: 10918–10922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tek, A. L., and J. Jiang, 2004. The centromeric regions of potato chromosomes contain megabase-size tandem arrays of telomere-similar sequence. Chromosoma 113: 77–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorgaard, G. H., F. W. Allendorf and K. L. Knudsen, 1983. Gene centromere mapping in rainbow trout; high interference over long map distance. Genetics 7: 524–530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Beek, J. G., R. Verkerk, P. Zabel and P. Lindhout, 1992. Mapping strategy for resistance genes in tomato based on RFLPs between cultivars: Cf9 (resistance to Cladosporium) on chromosome 1. Theor. Appl. Genet. 84: 106–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Os, H., S. Andrzejewski, E. Bakker, I. Barrena, G. J. Bryan et al., 2006. Construction of a 10,000-marker ultradense genetic recombination map of potato: providing a framework for accelerated gene location and a genomewide physical map. Genetics 173: 1075–1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Veen, J., and R. Hawley, 2003. Meiosis: when even two is a crowd. Curr. Biol. 13: R831–R833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veilleux, R. E., 1985. Diploid and polyploid gametes in crop plants: mechanisms of formation and utilization in plant breeding. Plant Breed. Rev. 3: 253–288. [Google Scholar]

- Voorrips, R. E., 2002. MapChart: software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 93: 77–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vos, P., R. Hogers, M. Bleeker, M. Reijans, T. van de Lee et al., 1995. AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res. 23: 4407–4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagenvoort, M., and E. Zimnoch-Guzowska, 1992. Gene-centromere mapping in potato by half-tetrad analysis: map distances of H1, Rx, and Ry and their possible use for ascertaining the mode of 2n-pollen formation. Genome 35: 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S., J. Wang, J. Jiang and Q. Zhang, 2000. Mapping of centromeric regions on the molecular linkage map of rice (Oryza sativa L.) using centromere-associated sequences. Mol. Gen. Genet. 263: 165–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe, K., and S. J. Peloquin, 1993. Cytological basis of 2n pollen formation in a wide range of 2x, 4x and 6x taxa from tuber-bearing Solanum species. Genome 36: 8–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, J. E., and S. J. Peloquin, 1991. Occurrence and mechanisms of 2n egg formation in 2x potato. Genome 34: 975–982. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., H. Yamagata, M. Hayschi-Tsugane, S. Hijlshita, M. Fujisawa et al., 2004. Composition and structure of the centromeric region of rice chromosome 8. Plant Cell 16: 967–976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]