Abstract

We present a new approach for estimation of the population-scaled mutation rate, θ, from microsatellite genotype data, using the recently introduced “product of approximate conditionals” framework. Comparisons with other methods on simulated data demonstrate that this new approach is attractive in terms of both accuracy and speed of computation. Our simulation experiments also demonstrate that, despite the theoretical advantages of full-likelihood-based methods, methods based on certain summary statistics (specifically, the sample homozygosity) can perform very competitively in practice.

PATTERNS of genetic variation in population samples contain important information on both the biological mechanisms (e.g., mutation, recombination, gene conversion, selection) and aspects of population demographic history (e.g., population expansions, bottlenecks, and migration rates). However, extracting this information is often tricky. The simplest methods are based on matching summaries of the data (e.g., expected heterozygosity or average pairwise distances between alleles) to their expected values. Although these methods are attractive in their simplicity, summarizing the genotype data with a single number in this way risks losing information. More complex methods that use sophisticated computations to approximate the full likelihood of the data (Griffiths and Tavaré 1994a,b; Kuhner et al. 1995; Iorio et al. 2005) are more efficient in principle, but typically are difficult to implement, and may take impractical amounts of time to produce reliable results (Stephens and Donnelly 2000; Fearnhead and Donnelly 2001). This has limited their usefulness in practice. Indeed, in some settings the computational complexities of full-likelihood-based approaches are so daunting that many researchers have turned to approximate methods (e.g., Hudson 2001; McVean et al. 2002; Fearnhead and Donnelly 2002; Li and Stephens 2003), often with considerable success (e.g., Crawford et al. 2004; McVean et al. 2004). Thus far, applications of these approximate methods have been to data on single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs). Here we extend one of these methods, the PAC likelihood approach of Li and Stephens (2003), to estimate the scaled mutation parameter θ (= 2Nμ, where N is the effective haploid population size and μ is the mutation probability per meiosis) from microsatellite data. Simulation results suggest that this method is as accurate as full-likelihood-based approaches and considerably faster.

Models and methods:

We consider a simple scenario, where we genotype a single microsatellite locus in n haploid individuals, or n/2 diploid individuals, sampled from a random-mating population that has been evolving neutrally with constant (haploid) size N according to a Wright–Fisher model. Let  denote the observed alleles (number of repeats of the microsatellite motif). We assume that the locus evolves according to a symmetric stepwise mutation mechanism, where if a mutation occurs in a transmission then the offspring's allele length increases or decreases (with equal probability) by one from the progenitor allele. Although this model is simplistic, it is widely used and is the basis for all the methods of estimating θ that we consider here. However, our approach could be easily modified to deal with other mutation models (e.g., those described in Calabrese and Durrett 2003).

denote the observed alleles (number of repeats of the microsatellite motif). We assume that the locus evolves according to a symmetric stepwise mutation mechanism, where if a mutation occurs in a transmission then the offspring's allele length increases or decreases (with equal probability) by one from the progenitor allele. Although this model is simplistic, it is widely used and is the basis for all the methods of estimating θ that we consider here. However, our approach could be easily modified to deal with other mutation models (e.g., those described in Calabrese and Durrett 2003).

There exist two broad categories of approach for estimating θ in this context. The first is moment estimators based on summary statistics. Kimmel et al. (1998) include two such estimators (their Equations 14 and 15). The first one, the homozygosity estimator, is given by

|

(1) |

where  is an unbiased estimate of the population homozygosity,

is an unbiased estimate of the population homozygosity,

|

(2) |

where r is the number of different alleles found in the population, and pi is the sample frequency of the ith allele. The second estimator is

|

(3) |

where  is the mean of the ai's. The estimator

is the mean of the ai's. The estimator  is based on the limiting expected homozygosity in a continuous-time Wright–Fisher model, whereas

is based on the limiting expected homozygosity in a continuous-time Wright–Fisher model, whereas  is based on the limiting expected value of the within-population component of genetic variance in the same model Kimmel

et al. (1998).

is based on the limiting expected value of the within-population component of genetic variance in the same model Kimmel

et al. (1998).

The second category is full-likelihood-based approaches, including maximum-likelihood and Bayesian approaches, which base inference on the likelihood

|

(4) |

In principle full-likelihood-based approaches are more efficient than moment estimators based on summary statistics. However, they are considerably harder to implement because the likelihood (4) cannot be computed directly. Instead, the likelihood can be approximated using computational methods such as Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) or importance sampling. Wilson and Balding (1998) and Beerli and Felsenstein (2001) describe two such approaches. Wilson and Balding (1998) take a Bayesian approach, specifying prior distributions for N and μ, and use an MCMC scheme to draw samples from the posterior distribution of θ. This method is implemented in the software MICSAT, which we downloaded from http://www.maths.abdn.ac.uk/∼ijw/downloads/download.htm. Beerli and Felsenstein (2001) also use a (different) MCMC scheme; but instead of performing a Bayesian analysis, they use it to compute a likelihood surface for θ (and also, in the case of samples from multiple populations, a set of migration rates among populations; however, here we deal with a sample from a single random-mating population, and so their approach can be used to estimate θ alone). This method is implemented by the program Migrate (version 1.7.3), which we downloaded from http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/lamarc/migrate.html.

In this article we take a different approach, following Li and Stephens (2003) who suggest approximating the likelihood (4) by exploiting the identity

|

(5) |

Although the conditional distributions on the right-hand side of this equation are unknown for most models of interest, they are amenable to approximation (e.g., Stephens and Donnelly 2000; Fearnhead and Donnelly 2001; Li and Stephens 2003). Substituting such an approximation,  say, into the right-hand side yields an approximate likelihood, which Li and Stephens (2003) term the “product of approximate conditionals” (PAC) likelihood:

say, into the right-hand side yields an approximate likelihood, which Li and Stephens (2003) term the “product of approximate conditionals” (PAC) likelihood:

|

(6) |

Li and Stephens (2003) applied this idea to estimate recombination rates (but not mutation rates) from SNP data and showed the resulting estimates to be competitive with the best available methods for that problem.

Here we show that an analogous approach also works for estimating θ from microsatellite data. For the conditional distributions  on the right-hand side of (6) we use the approximation suggested by Stephens and Donnelly (2000). This approximation is based on the idea that the next sampled allele, ak, will differ by a random number of mutations (which will typically be a small number of mutations and quite possibly 0 mutations) from a randomly chosen existing allele (

on the right-hand side of (6) we use the approximation suggested by Stephens and Donnelly (2000). This approximation is based on the idea that the next sampled allele, ak, will differ by a random number of mutations (which will typically be a small number of mutations and quite possibly 0 mutations) from a randomly chosen existing allele ( ). Stephens and Donnelly (2000, p. 616) assume that the number of mutations, m, has a geometric distribution, with Pr(m = 0) = k/(k + θ). The assumption of a geometric distribution is motivated by the fact that the resulting approximation is exact for the case k = 1; and the assumption on Pr(m = 0) is motivated by the fact that the resulting approximation is exact [and results in the well-known Ewens sampling formula (Ewens 1972)] for so-called “parent-independent mutation” (PIM) models, where the type of a mutant offspring is independent of the type of the progenitor allele. Of course, the stepwise mutation is not PIM, so the approximation is not exact in our setting. Part of our aim here is to show that the approximation is good enough to provide accurate estimates for θ.

). Stephens and Donnelly (2000, p. 616) assume that the number of mutations, m, has a geometric distribution, with Pr(m = 0) = k/(k + θ). The assumption of a geometric distribution is motivated by the fact that the resulting approximation is exact for the case k = 1; and the assumption on Pr(m = 0) is motivated by the fact that the resulting approximation is exact [and results in the well-known Ewens sampling formula (Ewens 1972)] for so-called “parent-independent mutation” (PIM) models, where the type of a mutant offspring is independent of the type of the progenitor allele. Of course, the stepwise mutation is not PIM, so the approximation is not exact in our setting. Part of our aim here is to show that the approximation is good enough to provide accurate estimates for θ.

Mathematically, the approximation suggested by Stephens and Donnelly (2000) is

|

(7) |

where qk = θ/(k + θ) and P is a mutation matrix, whose (i, j)th element is the probability that the type of an offspring is of type j, given that the progenitor is of type i and a mutation occurs. To ease comparison with other approaches, we assume a symmetric stepwise mutation mechanism, so that

|

We note that, unlike in Stephens and Donnelly (2000), we do not impose any reflecting boundaries on the mutation process, although this would be straightforward to do. (Thus, the matrix P has infinitely many rows and columns.) It would also be straightforward to incorporate nonstepwise moves (e.g., Nielsen 1997) or indeed any other desired form for P.

This choice of P has the convenient, although not essential, property that the approximation (7) simplifies, to

|

(8) |

This follows from rewriting (7) as

|

(9) |

and noting that the matrix with (i, j)th element

|

(10) |

is the inverse of (I − qP). Equation 10 can be verified by straightforward algebra, multiplying a row of (I − qP) by a column of (1 − qP)−1 defined by (10).

Substituting (8) into (6) for  gives a PAC likelihood for this problem. Note that, as in Li and Stephens (2003), the resulting PAC likelihood is not invariant to the ordering of the sampled alleles a1, a2, … , an. To deal with this, we take the same approach as Li and Stephens (2003); we average (4) over 10 random permutations of a1, a2, … , an. [Results (not shown) obtained using a single random permutation were similar in accuracy.] We use

gives a PAC likelihood for this problem. Note that, as in Li and Stephens (2003), the resulting PAC likelihood is not invariant to the ordering of the sampled alleles a1, a2, … , an. To deal with this, we take the same approach as Li and Stephens (2003); we average (4) over 10 random permutations of a1, a2, … , an. [Results (not shown) obtained using a single random permutation were similar in accuracy.] We use  to denote the value of θ that maximizes this function [found numerically by computing LPAC(θ) on a dense grid of values for θ].

to denote the value of θ that maximizes this function [found numerically by computing LPAC(θ) on a dense grid of values for θ].

Comparisons:

We compared the properties of our PAC-based estimator  with other available methods described above: the moment-based estimators

with other available methods described above: the moment-based estimators  and

and  and the full-likelihood-based estimators

and the full-likelihood-based estimators  and

and  . To be precise,

. To be precise,  is the mean of 10,000 draws from the posterior distribution for θ obtained using the program MICSAT with default parameter values, and

is the mean of 10,000 draws from the posterior distribution for θ obtained using the program MICSAT with default parameter values, and  is the value of θ that maximizes the approximate likelihood computed using Migrate, again with default parameter values.

is the value of θ that maximizes the approximate likelihood computed using Migrate, again with default parameter values.

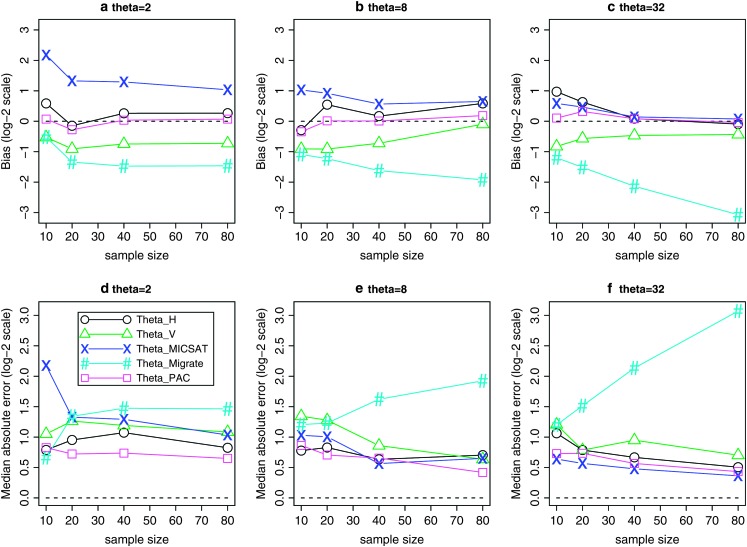

Figure 1 compares “bias” (or, more accurately, median error) and “accuracy” (median absolute error) of the resulting estimates, on a log scale. Making comparisons on the log scale means that, for example, underestimating θ by a factor of 2 is considered equally good—or bad—as overestimating by a factor of 2. We use medians rather than means because the means are infinite, due to the fact that there is a small finite probability of each estimator being 0 (and therefore giving a log of −∞); see also Li and Stephens (2003).

Figure 1.—

Comparison of the “bias” (a–c) and “accuracy” (d–f) of different estimators. Each section has five curves, one for each estimator: ○,  ; ▵,

; ▵,  ; x,

; x,  ; #,

; #,  ; and □,

; and □,  . In a–c the curves show the median value of

. In a–c the curves show the median value of  for different haploid sample sizes n = 10, 20, 40, and 80. In d–f each curve shows the median of

for different haploid sample sizes n = 10, 20, 40, and 80. In d–f each curve shows the median of  for the same values of n. We used a coalescent-based simulation program, kindly provided by P. Fearnhead, to simulate samples of microsatellite alleles randomly sampled from a population evolving according to the Wright–Fisher model, with stepwise mutation. (This model underlies all the methods we compare here.) For each different θ, and for each different n, we simulated 50 data sets. For each data set we estimated θ using each of the methods and compared the estimated value of θ with the true value of θ used to generate the data. Approximate run times for a single data set of size n = 80, on a desktop computer with 3GHz CPU, were ∼10 min for MICSAT, ∼45 min for Migrate, ∼10 sec for our method, and <1 sec for the summary statistic methods.

for the same values of n. We used a coalescent-based simulation program, kindly provided by P. Fearnhead, to simulate samples of microsatellite alleles randomly sampled from a population evolving according to the Wright–Fisher model, with stepwise mutation. (This model underlies all the methods we compare here.) For each different θ, and for each different n, we simulated 50 data sets. For each data set we estimated θ using each of the methods and compared the estimated value of θ with the true value of θ used to generate the data. Approximate run times for a single data set of size n = 80, on a desktop computer with 3GHz CPU, were ∼10 min for MICSAT, ∼45 min for Migrate, ∼10 sec for our method, and <1 sec for the summary statistic methods.

For the scenarios we consider,  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  are consistently better (smaller bias and smaller mean absolute error) than

are consistently better (smaller bias and smaller mean absolute error) than  and

and  . If anything the results for

. If anything the results for  seem very slightly better than the other three, especially for small values of θ (according to a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the improvement in accuracy over

seem very slightly better than the other three, especially for small values of θ (according to a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test, the improvement in accuracy over  is significant at P < 0.05 for all values of n considered at θ = 2 and for n = 10, 20, 80 at θ = 8; the improvement over

is significant at P < 0.05 for all values of n considered at θ = 2 and for n = 10, 20, 80 at θ = 8; the improvement over  is significant at P < 0.05 for all values of n considered at θ = 2, for n = 20, 80 at θ = 8, and for n = 10, 20, 40 at θ = 32). However, the differences may be too small to be practically important, and in some sense a direct comparison with

is significant at P < 0.05 for all values of n considered at θ = 2, for n = 20, 80 at θ = 8, and for n = 10, 20, 40 at θ = 32). However, the differences may be too small to be practically important, and in some sense a direct comparison with  is inappropriate, since it is based on a particular prior distribution for θ.

is inappropriate, since it is based on a particular prior distribution for θ.

One additional notable finding from our simulations is that, between the summary statistic estimators,  performs considerably better than

performs considerably better than  . Indeed, the finding that

. Indeed, the finding that  performs competitively with the likelihood-based methods is, as far as we are aware, novel. While we have no intuitive explanation for this good performance, the poor performance of

performs competitively with the likelihood-based methods is, as far as we are aware, novel. While we have no intuitive explanation for this good performance, the poor performance of  might perhaps have been expected, for the following reason. Equation 3 for

might perhaps have been expected, for the following reason. Equation 3 for  can be rewritten as

can be rewritten as  . Thus

. Thus  is the mean squared pairwise difference between sampled microsatellite repeats. In the context of sequence data, the corresponding estimate for θ (per base pair) is the mean pairwise distance (per base pair) between sampled haplotypes, also known as the nucleotide diversity, and this is known to be an inconsistent estimator for θ in that context (e.g., Donnelly and Tavaré 1995).

is the mean squared pairwise difference between sampled microsatellite repeats. In the context of sequence data, the corresponding estimate for θ (per base pair) is the mean pairwise distance (per base pair) between sampled haplotypes, also known as the nucleotide diversity, and this is known to be an inconsistent estimator for θ in that context (e.g., Donnelly and Tavaré 1995).

We interpret the poorer performance of  as indicating that, even in this relatively simple setting, with only a single parameter to be estimated and no migration, the default run lengths we used were insufficient to provide an accurate approximation to the maximum-likelihood estimates. In more complex settings, involving migration, for example, obtaining an accurate estimate of the likelihood surface, and the location of its maximum, seems likely to be still more challenging. Although some work would be necessary to extend our PAC-likelihood method to these settings, our results here, and in Li and Stephens (2003), suggest that this effort may be worthwhile.

as indicating that, even in this relatively simple setting, with only a single parameter to be estimated and no migration, the default run lengths we used were insufficient to provide an accurate approximation to the maximum-likelihood estimates. In more complex settings, involving migration, for example, obtaining an accurate estimate of the likelihood surface, and the location of its maximum, seems likely to be still more challenging. Although some work would be necessary to extend our PAC-likelihood method to these settings, our results here, and in Li and Stephens (2003), suggest that this effort may be worthwhile.

Acknowledgments

We thank two anonymous referees for helpful comments on the submitted version of this manuscript. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant HG/LM02585 to M.S.

References

- Beerli, P., and J. Felsenstein, 2001. Maximum likelihood estimation of a migration matrix and effective population sizes in n subpopulations by using a coalescent approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98(8): 4563–4568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese, P., and R. Durrett, 2003. Dinucleotide repeats in the drosophila and human genomes have complex, length-dependent mutation processes. Mol. Biol. Evol. 20 715–725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford, D., T. Bhangale, N. Li, G. Hellenthal, M. Rieder et al., 2004. Evidence for substantial fine-scale variation in recombination rates across the human genome. Nat. Genet. 36 700–706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnelly, P., and S. Tavaré, 1995. Coalescents and genealogical structure under neutrality. Annu. Rev. Genet. 29 401–421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewens, W. J., 1972. The sampling theory of selectively neutral alleles. Theor. Popul. Biol. 3 87–112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnhead, P. N., and P. Donnelly, 2001. Estimating recombination rates from population genetic data. Genetics 159 1299–1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fearnhead, P. N., and P. Donnelly, 2002. Approximate likelihood methods for estimating local recombination rates. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 64 657–680. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R. C., and S. Tavaré, 1994. a Ancestral inference in population genetics. Stat. Sci. 9 307–319. [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, R. C., and S. Tavaré, 1994. b Simulating probability distributions in the coalescent. Theor. Popul. Biol. 46 131–159. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson, R. R., 2001. Two-locus sampling distribution and their application. Genetics 159 1805–1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iorio, M. D., R. C. Griffiths, R. Leblois and F. Rousset, 2005. Stepwise mutation likelihood computation by sequential importance sampling in subdivided population models. Theor. Popul. Biol. 68 41–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel, M., R. Chakraborty, J. P. King, M. Bamshad, W. S. Watkins et al., 1998. Signatures of population expansion in microsatellite repeat data. Genetics 148 1921–1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhner, M. K., J. Yamato and J. Felsenstein, 1995. Estimating effective population size and mutation rate from sequence data using Metropolis–Hastings sampling. Genetics 140 1421–1430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, N., and M. Stephens, 2003. Modeling linkage disequilibrium, and identifying recombination hotspots using SNP data. Genetics 165 2213–2233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean, G., P. Awadalla and P. Fearnhead, 2002. A coalescent-based method for detecting and estimating recombination from gene sequences. Genetics 160 1231–1241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McVean, G. A. T., S. R. Myers, S. Hunt, P. Deloukas, D. R. Bentley et al., 2004. The fine-scale structure of recombination rate variation in the human genome. Science 304 581–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, R., 1997. A likelihood approach to population samples of microsatellite alleles. Genetics 146 711–716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephens, M., and P. Donnelly, 2000. Inference in molecular population genetics. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B 62 605–655. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, I. J., and D. J. Balding, 1998. Genealogical inference from microsatellite data. Genetics 150 499–510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]