Abstract

During meiotic prophase, assembly of the synaptonemal complex (SC) brings homologous chromosomes into close apposition along their lengths. The Zip1 protein is a major building block of the SC in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. In the absence of Zip1, SC fails to form, cells arrest or delay in meiotic prophase (depending on strain background), and crossing over is reduced. We created a novel allele of ZIP1, zip1-4LA, in which four leucine residues in the central coiled-coil domain have been replaced by alanines. In the zip1-4LA mutant, apparently normal SC assembles with wild-type kinetics; however, crossing over is delayed and decreased compared to wild type. The zip1-4LA mutant undergoes strong checkpoint-induced arrest in meiotic prophase; the defect in cell cycle progression is even more severe than that of the zip1 null mutant. When the zip1-4LA mutation is combined with the pch2 checkpoint mutation, cells sporulate with wild-type efficiency and crossing over occurs at wild-type levels. This result suggests that the zip1-4LA defect in recombination is an indirect consequence of cell cycle arrest. Previous studies have suggested that the Pch2 protein acts in a checkpoint pathway that monitors chromosome synapsis. We hypothesize that the zip1-4LA mutant assembles aberrant SC that triggers the synapsis checkpoint.

THE synaptonemal complex (SC) is a proteinaceous structure found along the lengths of homologous chromosomes during the pachytene stage of meiotic prophase. This elaborate structure, which is morphologically conserved across many eukaryotic species, holds homologous chromosomes in close proximity along their lengths (reviewed by Zickler and Kleckner 1999). Each SC consists of two lateral elements, corresponding to the proteinaceous cores of the individual chromosomes within the complex, separated by an intervening central region.

Another hallmark of meiotic prophase is meiotic recombination. This process is initiated by DNA double-strand breaks created by the topoisomerase II-like Spo11 protein (reviewed by Keeney 2001). After double-strand breaks are formed, a series of protein-catalyzed steps leads to the creation of two types of recombinants, crossovers and noncrossovers (Allers and Lichten 2001). Crossovers give rise to chromatin bridges between homologs that ensure their correct segregation at the first meiotic division. Failure to cross over can lead to nondisjunction and consequent inviability of meiotic products.

In budding yeast, recombination and chromosome synapsis are concurrent events (Padmore et al. 1991; Schwacha and Kleckner 1994). Double-strand breaks appear prior to the formation of mature SC. Joint molecules (Holliday junctions) are present when the SC is fully formed, and mature recombinants are produced around the time that the SC disassembles. Synapsis is not required for the initiation of recombination, but steps in the recombination pathway appear to be required for synapsis (reviewed by Roeder 1997; Zickler and Kleckner 1999).

In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Zip1 is a component of the central region of the SC (Sym et al. 1993). Zip1 is an 875-amino-acid protein with a predicted, α-helical coiled-coil domain flanked by globular domains. Zip1 forms a homodimer with the two proteins oriented in register; a pair of dimers lies head to head to span the space between lateral elements (Dong and Roeder 2000). The zip1 null mutation (herein referred to as zip1Δ) exhibits defects in chromosome synapsis, with chromosomes homologously paired, but not intimately synapsed. In the absence of Zip1, the cores of each pair of homologous chromosomes are closely associated at only a few sites (Sym et al. 1993), presumed to be the sites at which synapsis normally initiates (Chua and Roeder 1998; Fung et al. 2004). The zip1Δ mutant exhibits an approximately threefold decrease in meiotic crossing over compared to wild type, with the magnitude of the effect varying from interval to interval (Sym et al. 1993; Sym and Roeder 1994; Storlazzi et al. 1996).

During meiosis, a checkpoint mechanism arrests cells in midmeiotic prophase in response to defects in recombination (reviewed by Bailis and Roeder 2000). Mutants that accumulate unrepaired breaks with single-stranded tails (e.g., dmc1 and hop2) trigger the checkpoint and undergo delay or arrest in prophase (Bishop et al. 1992; Rockmill et al. 1995; Leu et al. 1998). Introduction of a spo11 mutation into these mutant backgrounds alleviates the arrest by preventing the initiation of recombination and the consequent accumulation of recombination intermediates (Bishop et al. 1992; Leu et al. 1998). Arrest can also be alleviated by mutations in the DDC1, MEC3, and RAD17 genes (Lydall et al. 1996; Thompson and Stahl 1999; Hong and Roeder 2002), whose products are involved in sensing DNA damage, such as unrepaired double-strand breaks (reviewed by Zhou and Elledge 2000).

Downstream targets of the checkpoint include Swe1 and Ndt80. During checkpoint activation, the Swe1 kinase accumulates and becomes hyperphosphorylated (Leu and Roeder 1999) and in turn phosphorylates Cdc28. This phosphorylation negatively regulates Cdc28 and limits the activity of the cyclin-dependent kinase complex Cdc28-Clb1 (Booher et al. 1993), whose activity is required for the exit from pachytene (Shuster and Byers 1989). Ndt80 is a meiotic transcription factor that activates genes required for exit from pachytene, including Clb1 (Chu and Herskowitz 1998; Hepworth et al. 1998). Activation of the pachytene checkpoint prevents the accumulation and Ime2-dependent phosphorylation of Ndt80 (Tung et al. 2000; Benjamin et al. 2003), thereby inhibiting Ndt80 activity.

Mutation of the meiosis-specific checkpoint PCH2 gene was identified on the basis of its ability to bypass the sporulation defect of the zip1Δ mutant (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999). Unlike the ddc1, mec3, and rad17 mutations, pch2 does not bypass the hop2 mutant arrest and has little or no effect on sporulation in the dmc1 mutant (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999; Zierhut et al. 2004; Hochwagen et al. 2005). Thus, its effect seems to be relatively specific for zip1. Studies in Caenorhabditis elegans, an organism in which synapsis is not dependent on recombination, revealed a checkpoint that specifically monitors chromosome synapsis, independently of a DNA-damage checkpoint (Bhalla and Dernburg 2005). This synapsis checkpoint requires the C. elegans homolog of PCH2. Recent studies led Wu and Burgess (2006) to propose that a Pch2-dependent synapsis checkpoint also operates in budding yeast.

We have generated and characterized a novel allele of the S. cerevisiae ZIP1 gene. This mutation, called zip1-4LA, results from changing four leucine residues in the coiled-coil region to alanines. This mutant makes SC with normal kinetics, but it nevertheless undergoes arrest at pachytene. Thus, zip1-4LA appears to uncouple the synapsis and sporulation functions of Zip1. The zip1-4LA mutant phenotype is fully suppressed by the pch2 mutation, leading us to propose that zip1-4LA makes an aberrant SC that triggers the synapsis checkpoint.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Genetic methods and strains:

Yeast manipulations were carried out using standard procedures (Sherman et al. 1986). Genotypes of relevant strains are presented in Table 1. Diploids were made by mating appropriate haploids, generated by transformation and/or genetic crosses.

TABLE 1.

Yeast strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Background | |

|---|---|---|---|

| BR2495a |

|

BR2495 | |

|

|||

| MY152b | BR2495 but homozygous zip1∷URA3 | BR2495 | |

| NMY101 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔB | BR2495 | |

| NMY102 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔC | BR2495 | |

| NMY103 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔD | BR2495 | |

| NMY104 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔE | BR2495 | |

| NMY105 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔF | BR2495 | |

| NMY106 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔG | BR2495 | |

| NMY107 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔH | BR2495 | |

| NMY109 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1ΔJ | BR2495 | |

| NMY111 | MY152 plus pRS315-ZIP1 | BR2495 | |

| NMY112 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1-4LA | BR2495 | |

| NMY113 | MY152 plus pRS315 | BR2495 | |

| NMY276 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1-L643A | BR2495 | |

| NMY278 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1-L650A | BR2495 | |

| NMY280 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1-L657A | BR2495 | |

| NMY282 | MY152 plus pRS315-zip1-L664A | BR2495 | |

| NMY274c |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

|

|||

| NMY363 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY364 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1∷URA3 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY233 |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY533 | NMY274 but homozygous ndt80∷LEU2 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY539 | NMY274 but homozygous ndt80∷LEU2 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY385 | NMY274 but homozygous spo11∷ADE2 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY422 | NMY274 but homozygous spo11∷ADE2 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY602 | NMY274 but homozygous rad17∷LEU2 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY605 | NMY274 but homozygous rad17∷LEU2 zip1∷URA3 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY608 | NMY274 but homozygous rad17∷LEU2 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY611 | NMY274 but homozygous ddc1∷ADE2 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY614 | NMY274 but homozygous ddc1∷ADE2 zip1∷URA3 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY617 | NMY274 but homozygous ddc1∷ADE2 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY644 | NMY274 but homozygous mec3∷TRP1 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY647 | NMY274 but homozygous mec3∷TRP1 zip1∷URA3 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY641 | NMY274 but homozygous mec3∷TRP1 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY340 | NMY274 but homozygous swe1∷KanMX4 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY345 | NMY274 but homozygous swe1∷KanMX4 zip1∷URA3 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY432 | NMY274 but homozygous swe1∷KanMX4 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY650d |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

|

|||

| NMY661 | NMY650 but homozygous pch2∷HphMX4 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY664 | NMY650 but homozygous pch2∷HphMX4 zip1∷KanMX4 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY654 | NMY650 but homozygous pch2∷HphMX4 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY562 | NMY274 but homozygous swe1∷KanMX4 pch2∷URA3 zip1-4LA | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY559 | NMY274 but homozygous swe1∷KanMX4 pch2∷URA3 zip1∷LYS2 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY565 | NMY274 but homozygous swe1∷KanMX4 pch2∷URA3 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY268e | NMY274 but MATα-bearing chromosome III is circular | BR1919-8B 2n | |

|

|||

| NMY270 |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY272 |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY671 |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY672 | NMY268 but homozygous pch2-HphMX4 zip1-KanMX4 | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY673 |

|

BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY471f | NMY274 but MATα-bearing chromosome III is circular and congenic with | ||

|

BR1919-8B 2n | ||

| NMY472f | NMY274 but MATα-bearing chromosome III is circular and congenic with | ||

|

BR1919-8B 2n | ||

| NMY473f | NMY274 but MATα-bearing chromosome III is circular and congenic with | ||

|

BR1919-8B 2n | ||

| NMY401 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1-ΔC | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY402 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1-ΔD | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY403 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1-ΔE | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY404 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1-ΔF | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY405 | NMY274 but homozygous zip1-ΔJ | BR1919-8B 2n | |

| NMY461g |

|

SK1 | |

|

|||

| NMY462g |

|

SK1 | |

|

|||

| NMY463g |

|

SK1 |

BR2495 was described by Rockmill and Roeder (1990). The MATα parent of BR2495 is BR1919-8B (Rockmill and Roeder 1990).

MY152 was described by Sym and Roeder (1995).

NMY274 is a diploid strain whose MATα haploid parent is isogenic with BR1919-8B (Rockmill and Roeder 1990) and whose MATa haploid parent was generated by switching the mating type of BR1919-8B (Rockmill et al. 1995).

NMY650 is isogenic with NMY274 except for the markers noted, including a copy of ADE2 inserted at an ectopic location on chromosome III (designated iADE2).

NMY268 is a diploid consisting of a MATα strain isogenic with BR1919-8B that carries a circular version of chromosome III and is spo13∷URA3 mated to MATa BR1919-8B.

NMY471–NMY473 are diploids consisting of a MATα strain congenic with BR1919-8B that carries a circular version of chromosome III and is swe1∷KanMX4 zip1∷LEU2 mated to MATa BR1919-8B strains that are swe1∷KanMX4 and ZIP1 (NMY471) or zip1-4LA (NMY472) or zip1∷URA3 (NMY473).

NMY461–NMY463 are isogenic with SK1 (Alani et al. 1987).

The following gene deletion/disruption constructs were described previously: pML54 for mec3∷TRP1 (Longhese et al. 1996), pTP89 for ndt80∷LEU2 (Tung et al. 2000), pSS52 for pch2∷URA3 (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999), pDL183 for rad17∷LEU2 (Lydall and Weinert 1997), pME302 for spo11∷ADE2 (Engebrecht and Roeder 1989), p(spo13)16 for spo13∷URA3 (Wang et al. 1987), pMB97 for zip1∷LEU2 (Sym et al. 1993), pMB116 for zip1∷LYS2 (Sym and Roeder 1994), and pMB117 for zip1∷URA3 (Sym and Roeder 1995).

The ddc1∷ADE2 disruption plasmid pB219 was created by Beth Rockmill as follows. The SphI–BamHI fragment of DDC1 was cloned between the SphI and BamHI sites of the SK+ plasmid (Stratagene, Cedar Creek, TX) to yield pB215. The SmaI–PstI fragment of ADE2 was then subcloned into pB215 between the HpaI and PstI sites to yield pB219, which was then cut with XmaI and SphI for targeting gene disruption in yeast. The zip1∷KanMX4, swe1∷KanMX4, and pch2∷HphMX4 disruptions were created by transformation with PCR products derived from the KanMX4 and HphMX4 drug resistance cassettes (Wach et al. 1994; Goldstein and McCusker 1999). For zip1∷KanMX4 and pch2∷HphMX4, primers extending 40 nucleotides inward from the start and stop codons of ZIP1 and PCH2 were used to delete almost all of the coding sequence of each gene. For swe1∷KanMX4, primers complementary to untranslated regions flanking SWE1 were used such that the entire gene was deleted.

In-frame deletions of ZIP1 and zip1-4LA:

In-frame deletions of ZIP1 were created by PCR amplification of plasmid pHD130(T7), which consists of the ZIP1 HincII–HincII fragment (nucleotides 1534–2472) inserted into the unique SmaI site of pQE30(T7). The pQE30(T7) plasmid is a modified version of pQE30 (QIAGEN, Valencia, CA) in which the nucleotides between the XhoI and EcoRI sites flanking the T5 promoter were replaced with a T7 promoter and lac operator sequence specified by the following oligonucleotide: 5′-CTCGAGAAATTAATACGACTCACTATAGGCCTGGAATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTCCGAATTC-3′. For each deletion, 5′-phosphorylated primers oriented outward from the site of the intended deletion were used to amplify ∼4.4 kb of DNA, which was then circularized by T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA). Template DNA was degraded using DpnI (New England Biolabs). To ensure fidelity of replication, Pfu Turbo DNA polymerase (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used; the resulting plasmids were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

Deletion constructs were then transferred into the context of full-length ZIP1 as follows. The pRS315 vector (Sikorski and Hieter 1989) was modified to create plasmid pRS315-EPN by replacing the nucleotide sequence between EagI and XhoI with an oligonucleotide containing EagI, PstI, and NheI sites but no XhoI site: 5′-CGGCCGAACTGCAGAAGCGAGCTAGCAAGTCGAG-3′. Full-length ZIP1 and flanking sequence were removed from plasmid pMB96 (Sym et al. 1993) by digestion with PstI and XbaI and inserted into pRS315-EPN between the PstI and NheI sites, thus destroying both the NheI and XbaI sites and creating pRS315-EPN-Zip1. Three restriction sites (that do not alter the encoded amino acids) were introduced into the 3′ end of ZIP1 at positions 2389 (XbaI), 2478 (AvaI), and 2592 (HindIII) using overlap PCR (Ho et al. 1989) to create pRS315-EPN-Zip1(mut). The deletion constructs were transferred into pRS315-EPN-Zip1(mut) by gap repair (Oldenburg et al. 1997). A gap of 23 bp was created by digestion with Bsu36I (2365) and XbaI (2389). The digested plasmid was cotransformed into MY152 with PCR products (corresponding to ZIP1 nucleotides 1534–2472) amplified from the pQE(T7) plasmids containing each deletion. The resulting constructs are shown in Figure 1A and the corresponding strains are NMY101–NMY109. Strains NMY111 and NMY113 were used as positive and negative controls, respectively. Deletion constructs zip1-ΔC, zip1-ΔD, zip1-ΔE, zip1-ΔF, and zip1-ΔJ were substituted into the genome in the same manner as zip1-4LA (see below) to yield strains NMY401–NMY405.

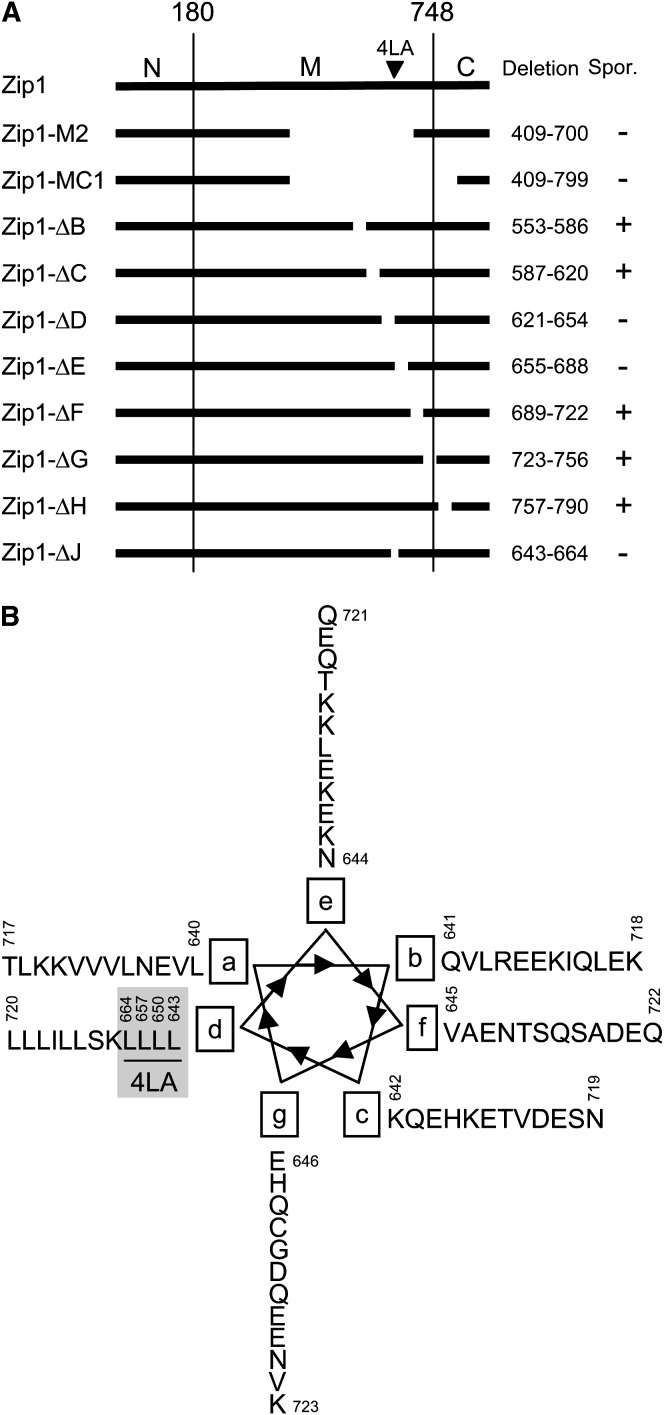

Figure 1.—

Structure of Zip1 deletion mutants. (A) Full-length Zip1 protein (875 amino acids) is indicated at the top as a solid line. Vertical lines separate the three domains (N, amino-terminal globular domain; M, middle coiled-coil domain; C, carboxy-terminal globular domain). The arrowhead indicates the position of the 4LA mutation. In-frame deletions are shown by gaps in the solid line, and the deleted amino acid residues are indicated on the right. The ability of each mutant to sporulate (Spor.) in the BR2495 strain background is noted with a + or a − on the far right. Strains used are NMY101–NMY109. Data for Zip1-M2 and Zip1-MC1 are taken from Tung and Roeder (1998). (B) Zip1 residues 640–723 plotted as an α-helical wheel (Landschulz et al. 1988; Alber 1992). The four leucines that were changed to alanines in zip1-4LA are underlined and shaded.

For the creation of zip1-4LA, site-directed mutagenesis was performed on pRS315-EPN-Zip1(mut) using overlap PCR (Ho et al. 1989) to replace the codons for leucine with those for alanine at the appropriate positions (L643A, L650A, L657A, and L664A). The resulting plasmid was transformed into MY152 to yield NMY112. To substitute zip1-4LA into the genome, a MATα BR1919-8B zip1∷URA3 haploid strain was transformed with linear, double-stranded DNA containing the full-length zip1-4LA gene and transformants were selected on 5-FOA (Toronto Research Chemicals, Toronto) to select for loss of the URA3 marker (Boeke et al. 1984). A correct transformant was then crossed to a wild-type BR1919-8B MATa strain to derive a zip1-4LA strain of the opposite mating type. Two zip1-4LA BR1919-8B-derived haploids of opposite mating type were then mated, resulting in strain NMY363.

To assess the presence of the zip1-4LA allele in meiotic products of heterozygous diploids, primers specific to zip1-4LA, nucleotides 1950–1970 (5′-GAAGGCTCATGAATTGGAGGC-3′) and to the 3′ end of ZIP1, nucleotides 2606–2628 (5′-CTATTTCCTTCTCCTTTTCTTGC-3′) were used. These primers generate a PCR product of 679 bp, diagnostic of the presence of zip1-4LA. Wild-type ZIP1 is not amplified.

To integrate zip1-4LA into SK1, the full-length zip1-4LA gene was subcloned into pRS306 (Sikorski and Hieter 1989) between the SacII and KpnI sites and then integrated at the URA3 locus (targeted using BsmI) of haploid zip1∷LYS2 SK1 strains. The strains were then mated, resulting in strain NMY462. Control strains were likewise created, using ZIP1 subcloned into pRS306 at the same sites (NMY461) or using an empty pRS306 vector (NMY463).

To create zip1-L643A, zip1-L650A, zip1-L657A, and zip1-L664A, pRS315-EPN-Zip1 was modified as follows. The PstI site was destroyed by digestion with PstI, followed by treatment with the large Klenow fragment of DNA polymerase I (New England Biolabs) to remove the 3′ overhangs. The vector was recircularized by T4 DNA Ligase (New England Biolabs) to yield pRS315-EN-Zip1. Next, three restriction sites that do not alter the encoded amino acids were introduced at ZIP1 positions 1918 (PstI), 2001 (XbaI), and 2107 (HindIII), using overlap PCR (Ho et al. 1989). For each point mutant, the sequence between the PstI and XbaI sites in pRS315-EN-Zip1 was replaced by a double-stranded oligonucleotide with appropriate overhanging ends, generated by annealing complementary oligonucleotides containing the required codon. The resulting plasmids were transformed into a BR2495 strain in which ZIP1 was deleted, resulting in strains NMY276, NMY278, NMY280, and NMY282.

Sporulation and spore viability:

Sporulation was performed at 30° in liquid sporulation medium (SPM) (2% potassium acetate, pH 7.0) for nuclear division assays, for spreads of meiotic nuclei, and for physical recombination assays. All other sporulation was performed on SPM in agar plates at 30° for 2 days. The dityrosine assay (Esposito et al. 1991) was used to assay the presence or absence of spores for zip1 deletion mutants. Yeast spore walls include a macromolecule containing dityrosine, which fluoresces under UV light. Patches of cells were placed on top of a nitrocellulose filter on SPM plates and allowed to sporulate for 2 days. Fluorescence was viewed with a UV light source (302 nm) and photographed through a blue Wratten 47b gelatin filter (Kodak, Rochester, NY). For quantification of sporulation, at least 200 cells for each strain were assayed by phase-contrast microscopy for each experiment; every experiment was performed in triplicate.

Spore viability was determined by tetrad dissection. The numbers of spores scored were 880 for wild type, 1144 for pch2, 1144 for pch2 zip1-4LA, 2640 for pch2 zip1, and 176 each for all other strains analyzed for viability.

Cytology:

To determine the kinetics of meiotic nuclear division, cells were fixed in 50% ethanol and frozen at −20° prior to staining with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (Hong and Roeder 2002). Cells were visually scored using a fluorescence microscope (Nikon E800, see below). For each experiment, at least 100 nuclei per strain per time point were scored. Each experiment was performed three times.

Spread meiotic nuclei were prepared and stained with antibodies as described by Dresser and Giroux (1988). Chromosomal DNA was visualized by staining with DAPI. For Figure 2B, affinity-purified, mouse polyclonal anti-Zip1 antibody (Chua and Roeder 1998) was used at 1:100 dilution, and rabbit polyclonal anti-Red1 antiserum (Smith and Roeder 1997) was used at 1:400 dilution. Donkey anti-mouse antibody conjugated to FITC and donkey anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Texas Red were used at 1:200 dilution (both from Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs, West Grove, PA). For Figure 3A, affinity-purified, rabbit polyclonal anti-Zip1 antibody (Sym et al. 1993) was used at 1:50 dilution, and rat anti-tubulin antibody (Sera-Lab, West Sussex, UK) was used at 1:400 dilution. Donkey anti-rabbit antibody conjugated to Texas Red and donkey anti-rat antibody conjugated to FITC (both from Jackson ImmunoResearch Labs) were used at 1:200 dilution.

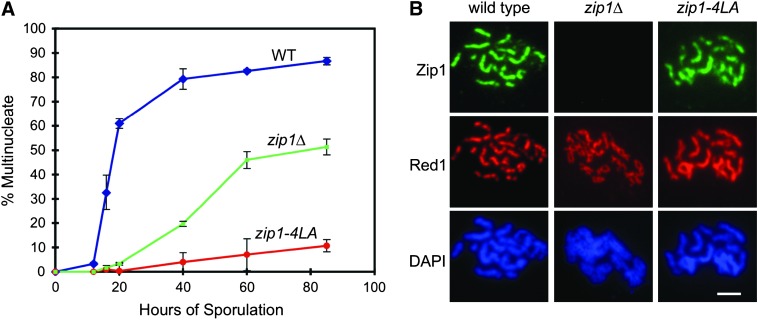

Figure 2.—

zip1-4LA exhibits defects in nuclear division yet has synapsed chromosomes. (A) Nuclear division assay of WT (NMY274, blue), zip1Δ (NMY364, green), and zip1-4LA (NMY363, red) strains in the BR1919-8B diploid background. The graph shows the percentage of cells having completed one or both nuclear divisions as a function of time. (B) Examples of spread nuclei after 18 hr of sporulation. Zip1 (green), Red1 (red), and DAPI (blue) staining are shown for WT, zip1Δ, and zip1-4LA strains. Bar, 1 μm.

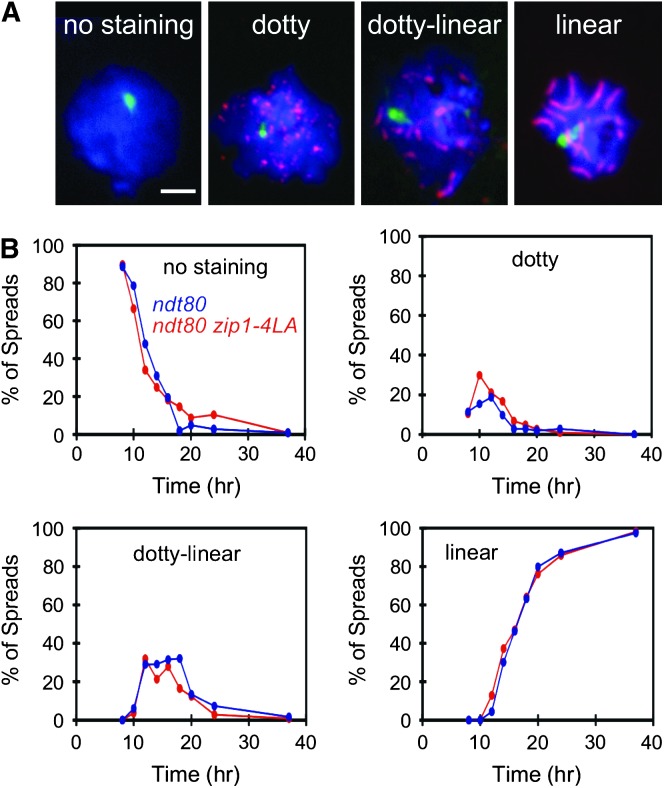

Figure 3.—

Kinetics of SC formation. (A) Nuclear spreads were prepared for ndt80 (NMY539) and ndt80 zip1-4LA (NMY533) BR1919-8B diploid strains harvested at nine different time points after the introduction into sporulation medium. Nuclei were stained for Zip1 (red), tubulin (green), and DAPI (blue) and placed into four categories on the basis of Zip1 staining: no staining, dotty (punctate Zip1 foci), dotty linear (Zip1 foci and some elongated stretches of Zip1), and linear (fully elongated Zip1). Bar, 1 μm. (B) Plots of the percentage of ndt80 (blue) and ndt80 zip1-4LA (red) nuclei in each category as a function of time.

A Nikon E800 microscope, equipped with a 100× Plan Apo objective lens, epifluorescence optics, and a Chroma 86012 filter set (Micro Video Instruments, Avon, MA), was used to observe antibody-stained meiotic chromosomes. Images were captured by a Photometrics Cool Snap HQ CCD camera and processed with IPLab Spectrum software v.3.9.5r2 (BD Bioscience, Franklin Lakes, NJ).

For the time-course experiment to monitor the kinetics of SC formation (Figure 3), multiple nuclear spreads were photographed in one field of view and then scored individually. Nine different time points were assayed in each of two independent experiments. At each time point, at least 100 nuclear spreads were scored for each strain, NMY533 and NMY539. The total numbers of spreads scored were 2614 for experiment A and 1966 for experiment B. The results of the two experiments were qualitatively similar, and the data for experiment B are presented in Figure 3B.

Physical recombination assays:

The assays were performed as previously described by Tsubouchi et al. (2006). Briefly, Southern blot analysis was carried out using a radiolabeled probe for chromosome III, prepared as described by Agarwal and Roeder (2000). Blots were visualized and crossover products were quantified by phosphorimaging in a Storm 860 Gel and Blot Imaging System and using ImageQuant software (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Piscataway, NJ). Physical assays were performed at least three times for each experiment, and the results obtained were qualitatively similar.

Genetic analysis:

Crossover frequencies were determined by tetrad dissection for four intervals (chromosome III, HIS4-LEU2, LEU2-MAT, MAT-ADE2; chromosome VIII, ARG4-THR1). The numbers of tetrads dissected were 220 for wild type, 286 for pch2, 286 for pch2 zip1-4LA, and 660 for pch2 zip1. Distributions of tetrad types (parental ditype, nonparental ditype, tetratype) were compared using the G-test of homogeneity (e.g., Sokal and Rohlf 1995), using a Microsoft Excel calculator created by Ed Louis and Faiz Abdullah, to assess statistical differences among the four strains.

RESULTS

Deletion analysis of ZIP1:

Previous deletion analysis of ZIP1 revealed that deletions of amino acid residues 409–700 (zip1-M2) and 409–799 (zip1-MC1), affecting the coiled-coil region, cause cells to arrest at pachytene (Tung and Roeder 1998). To narrow further the region within the coiled coil responsible for cell cycle arrest, seven smaller in-frame deletions of 34 codons each were created (Figure 1A), inserted into a centromere-containing plasmid, and introduced into a BR2495 strain background in which the ZIP1 gene is deleted. Strains carrying these zip1 deletion constructs were examined for sporulation by a dityrosine assay (Esposito et al. 1991). (Yeast spore walls include a macromolecule containing dityrosine, which fluoresces under UV light.) zip1-ΔD (Δ621–654) and zip1-ΔE (Δ655–688) each cause sporulation arrest, whereas constructs with deletions immediately upstream (ΔB and ΔC) and downstream (ΔF and ΔG) of regions D and E do not trigger arrest. A smaller deletion of 22 residues, zip1-ΔJ (Δ643–664), was created that partially overlaps both regions D and E. The zip1-ΔJ mutant also arrests.

Examination of the Zip1 amino acid sequence in regions D–F reveals a motif resembling a leucine zipper, although there is no adjacent stretch of basic residues as observed in the canonical leucine zipper motif (Landschulz et al. 1988; Alber 1992). When an α-helical wheel is plotted for Zip1 residues 640–723 (approximately regions D–F), it is evident that leucines are present at position d of the helix in many cases (Figure 1B). A new mutant was constructed in which the four leucines at position d within region J were replaced by alanines. The mutant, called zip1-4LA (L643A, L650A, L657A, L664A), was assayed for sporulation by phase-contrast microscopy; zip1-4LA is unable to sporulate in the BR2495 strain background.

The zip1Δ mutant is unable to sporulate in BR2495, but it is able to sporulate at low levels (∼5%) in the BR1919-8B diploid strain background (B. Rockmill, personal communication). To examine the effect of zip1-4LA in this background, a BR1919-8B diploid homozygous for zip1-4LA (substituted for the wild-type ZIP1 gene on the chromosome) was constructed and analyzed. Surprisingly, even in this strain background, zip1-4LA (NMY363) completely fails to sporulate, demonstrating that zip1-4LA causes a tighter arrest than the zip1Δ mutant (NMY364). In the SK1 strain background, zip1Δ does sporulate, after a delay and with reduced efficiency (Sym and Roeder 1994; Storlazzi et al. 1996; Xu et al. 1997). The zip1-4LA mutant sporulates less efficiently than zip1Δ in SK1: 30.9% for zip1-4LA (NMY462) vs. 48.5% for zip1Δ (NMY463) and 94.8% for wild type (NMY461). Using the homogeneity chi-square test, the difference in sporulation between zip1Δ and zip1-4LA is statistically significant (P = 0.004).

To determine if the zip1-4LA mutation is dominant, a BR1919-8B diploid heterozygous for zip1-4LA was constructed (NMY233). This strain does not arrest, demonstrating that zip1-4LA is not dominant for sporulation arrest.

zip1-4LA undergoes meiotic cell cycle arrest with synapsed chromosomes:

Nuclear division assays were performed to compare meiotic progression in zip1-4LA with wild type and the zip1Δ mutant in the BR1919-8B diploid background (Figure 2A). Whole cells were monitored at different time points after the transfer to SPM by staining with the DNA-binding dye, DAPI. In the zip1Δ mutant, meiotic division is delayed by ∼20 hr compared to wild type, and zip1-4LA is almost completely arrested prior to the meiosis I division. Although zip1-4LA does not form asci as observed by phase-contrast microscopy, ∼10% of zip1-4LA nuclei do appear to go through at least the first meiotic division. This observation may be an artifact of the assay (DAPI-stained nuclei appear more fragmented at late time points in all strains, and cells are difficult to categorize). Alternatively, a subpopulation of cells may undergo meiotic division, but nevertheless fail to sporulate.

To determine if chromosomes are synapsed in the zip1-4LA mutant, meiotic nuclei were surface spread, stained with antibodies to Zip1 and to the chromosomal core protein Red1 (Smith and Roeder 1997), and then visualized by fluorescence microscopy. Synapsis was assessed after 18 hr in sporulation medium, when the number of wild-type cells in pachytene is maximal (Figure 2B). The zip1-4LA mutant exhibits fully synapsed chromosomes decorated along their lengths with anti-Zip1 antibodies. In some nuclear spreads, Red1 staining appears more continuous in zip1-4LA than in wild type, consistent with previous observations that Red1 accumulates when meiotic progression is delayed (Smith and Roeder 1997; Chua and Roeder 1998).

Spread nuclei were also examined for the presence of polycomplexes, which are ordered aggregates of SC proteins unassociated with chromosomes (Sym and Roeder 1995; Dong and Roeder 2000). Failure to form SC, or a delay in SC formation, leads to the formation of polycomplexes (Loidl et al. 1994; Chua and Roeder 1998). These structures are not observed in the zip1-4LA mutant, indicating that there is no gross defect or delay in SC assembly. The Zip1-4LA protein is capable of assembling into polycomplexes, as evidenced by the fact that the spo11 zip1-4LA double mutant (NMY385) does make polycomplexes (data not shown).

SC assembles with wild-type kinetics in zip1-4LA:

To investigate further the kinetics of SC assembly, nuclear spreads were analyzed at various time points. zip1-4LA cells arrest at pachytene whereas wild-type cells progress out of pachytene. Thus, to compare the kinetics of SC formation in wild-type and zip1-4LA strains, the ndt80 mutation was introduced into both strains. In the ntd80 background, cells arrest at pachytene (Xu et al. 1995), thus preventing SC disassembly in ZIP1 cells.

Both DAPI and Zip1 staining were used to identify spread nuclei. Each spread nucleus was assigned to one of four categories on the basis of the extent of Zip1 staining. Zip1 staining was classified as “no staining” (no Zip1 foci or linear stretches), “dotty” (many individual foci), “dotty linear” (some foci and at least one linear stretch), or “linear” (all staining in linear stretches). No staining, dotty, dotty linear, and linear represent progressively later stages in SC formation. An example of each category is shown in Figure 3A.

The percentage of total spreads in each category of Zip1 staining was plotted as a function of time. The data from one time course are shown in Figure 3B. The zip1-4LA ndt80 and ndt80 strains exhibit the same rate of SC assembly. Furthermore, no polycomplexes were observed in either strain at any of the time points examined. Thus, there is no defect or delay in SC formation in the zip1-4LA mutant.

In a spo11 mutant, the Zip1 protein localizes only to foci on chromosomes, and these foci correspond to the locations of centromeres (Tsubouchi and Roeder 2005). The Zip1-4LA protein also localizes at or near centromeres in a spo11 background (data not shown), indicating that this aspect of Zip1 function is not impaired in the zip1-4LA mutant.

Bypass of the pachytene checkpoint alleviates the arrest of zip1-4LA:

In the absence of Spo11, recombination is not initiated, SC is not formed, and the pachytene checkpoint is not activated (reviewed by Bailis and Roeder 2000). To determine if the arrest of zip1-4LA can be overcome by preventing checkpoint activation, a spo11 zip1-4LA double mutant (NMY385) was assayed for sporulation. The double mutant is able to sporulate similarly to the spo11 single mutant (NMY422), indicating that arrest of zip1-4LA is dependent on some aspect of recombination and/or synapsis. The mere presence of Zip1-4LA protein in the cell is not sufficient to trigger meiotic arrest.

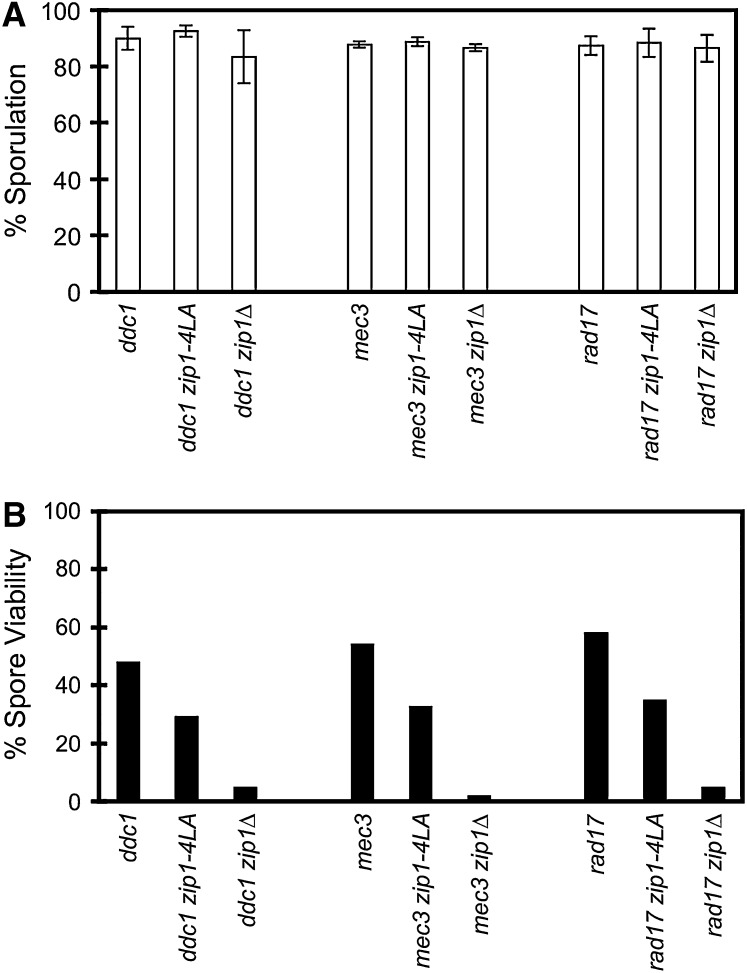

The DDC1, MEC3, and RAD17 genes are involved in sensing DNA damage, such as unrepaired double-strand breaks (reviewed by Zhou and Elledge 2000). Each of these genes was knocked out in a zip1-4LA background, and the resulting double mutants were assayed for sporulation and spore viability (Figure 4). All of the double mutants are able to sporulate at wild-type levels, indicating that ddc1, mec3, and rad17 are each able to bypass the arrest of zip1-4LA (Figure 4A). However, in every case, the viability of the double mutant is only ∼60% of that of the corresponding ddc1, mec3, or rad17 single mutant (Figure 4B). The ddc1, mec3, and rad17 mutations by themselves cause a reduction in spore viability compared to wild type (Figure 4B; Lydall et al. 1996; Thompson and Stahl 1999; Hong and Roeder 2002).

Figure 4.—

Sporulation and spore viability. Shown are sporulation (A) and spore viability (B) data for ddc1 (NMY617), mec3 (NMY641), and rad17 (NMY608) single mutants as well as for the same mutants in combination with zip1-4LA (NMY611, NMY644, NMY602) or zip1Δ (NMY614, NMY647, NMY605). All strains are in the BR1919-8B diploid background. Error bars represent standard deviations.

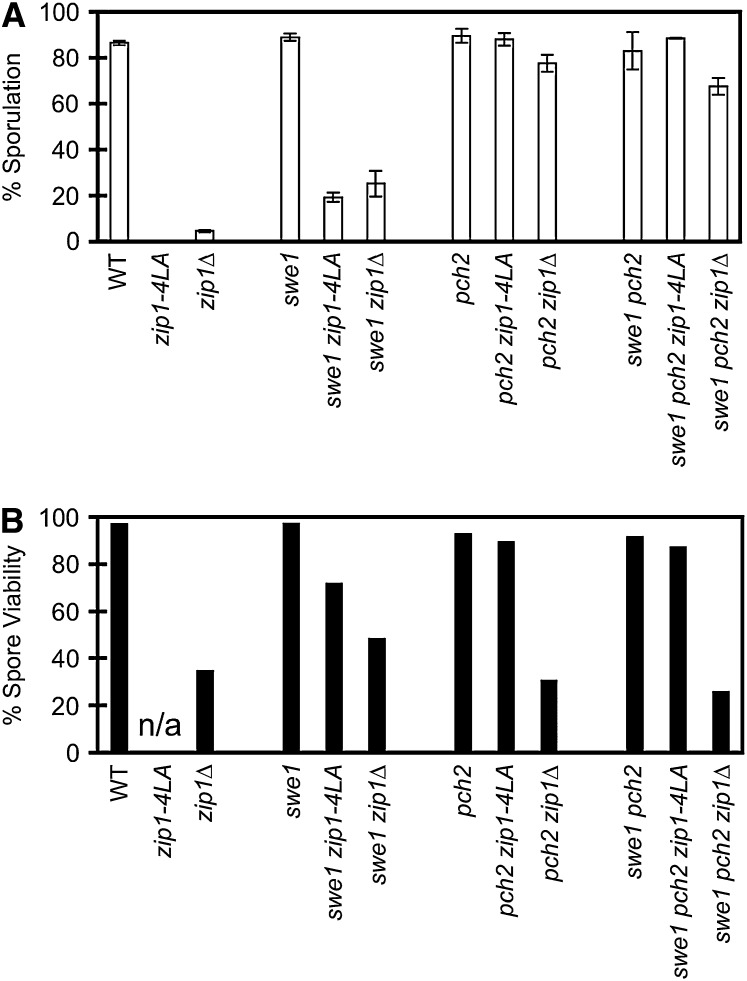

Mutation of the SWE1 gene, whose product acts downstream in the checkpoint pathway (Leu and Roeder 1999), was also tested for its ability to bypass zip1-4LA. The swe1 mutation by itself does not affect sporulation or spore viability (Leu and Roeder 1999). The swe1 zip1-4LA double mutant is able to sporulate, but at a low level (19.2%) (Figure 5A). The viability of the spores produced is 72.2%, compared to 97.7% in swe1 and 48.9% in swe1 zip1Δ (Figure 5B). Although deletion of swe1 can partially bypass the meiotic arrest of zip1-4LA, the low level of sporulation and the reduction in spore viability in swe1 zip1-4LA suggest that bypass of the checkpoint by swe1 is not sufficient to alleviate all the defects of zip1-4LA.

Figure 5.—

Sporulation and spore viability. Shown are sporulation (A) and spore viability (B) data for wild type (NMY274), zip1-4LA (NMY363), zip1Δ (NMY364), swe1 (NMY432), swe1 zip1-4LA (NMY340), swe1 zip1Δ (NMY345), pch2 (NMY654), pch2 zip1-4LA (NMY661), pch2 zip1Δ (NMY664), swe1 pch2 (NMY565), swe1 pch2 zip1-4LA (NMY562), and swe1 pch2 zip1Δ (NMY559). All strains are in the BR1919-8B diploid background. Error bars represent standard deviations. n/a, not applicable.

Deletion of the meiosis-specific checkpoint protein Pch2 relieves the pachytene arrest of the zip1Δ mutant (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999). To determine if pch2 can bypass the meiotic arrest of zip1-4LA, the pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant was assayed for sporulation (Figure 5A) and spore viability (Figure 5B). Sporulation occurs at wild-type levels in the double mutant, indicating that meiotic arrest of zip1-4LA is fully bypassed by pch2. Furthermore, the viability of the resulting spores is very high (89.8%), similar to (but statistically different from) the viability of spores from the pch2 single mutant (93.3%) (P = 5.6 × 10−5, chi-square contingency test).

The swe1 pch2 zip1-4LA triple mutant is indistinguishable from the pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant. Thus pch2 is epistatic to swe1, consistent with the notion that Swe1 acts downstream of Pch2.

pch2 suppresses the recombination defect of zip1-4LA:

The zip1Δ mutation reduces, but does not abolish, crossing over (Sym et al. 1993; Sym and Roeder 1994; Storlazzi et al. 1996). To examine the effect of zip1-4LA on recombination, crossing over was assessed in a physical assay (Game et al. 1989) using a strain isogenic to the BR1919-8B diploid in which one copy of chromosome III has been circularized. Single crossovers result in a dimeric chromosome III, and three-stranded double crossovers result in a trimeric chromosome III (see materials and methods). These products can be detected by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis followed by Southern blot analysis.

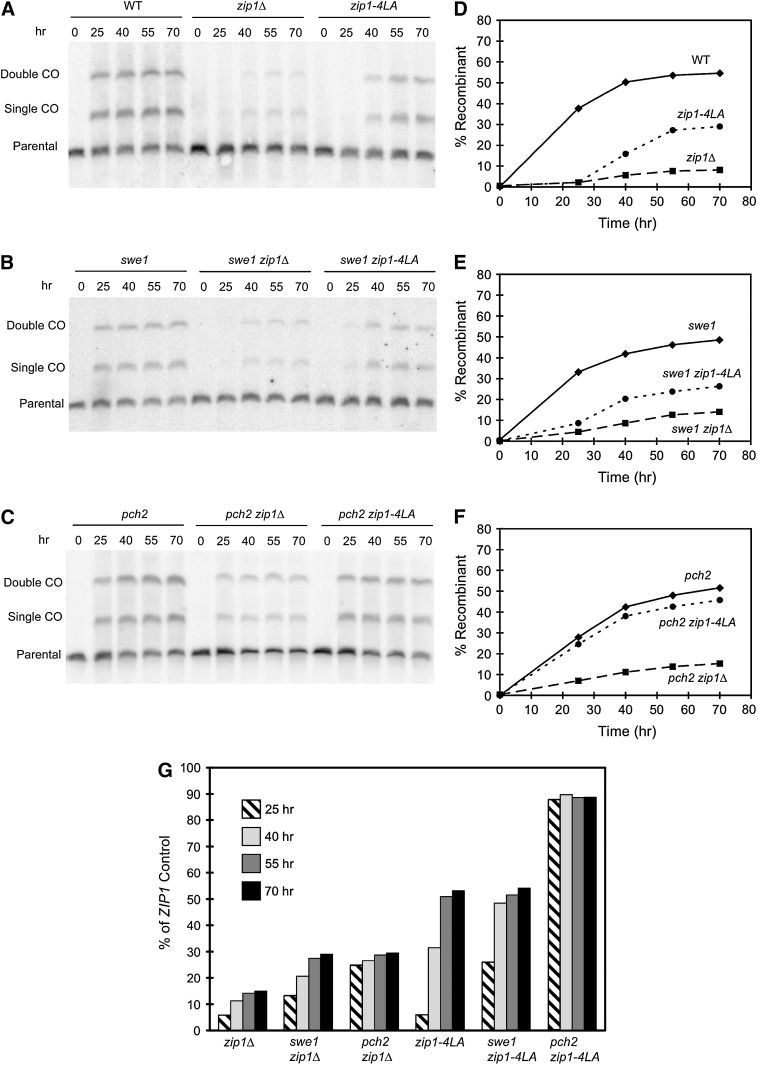

As shown in Figure 6A, the zip1Δ mutant shows a significant delay in the appearance of crossover products, and the overall level of crossing over is reduced substantially compared to wild type, even at late time points (Figure 6A). The zip1-4LA mutant shows a delay in crossing over similar to that of zip1Δ, but the absolute level of crossovers is higher for zip1-4LA than for zip1Δ (Figure 6A). The amount of signal in each band was quantified using densitometry. The total signal in the recombinant bands was calculated as a percentage of the total signal in all three bands and then plotted as a function of time (Figure 6D). zip1-4LA reaches only ∼53% of the wild-type level of crossovers (Figure 6G), even after 70 hr of sporulation. At the same time, crossing over in zip1Δ is only 15% of wild type (Figure 6G).

Figure 6.—

Physical assay of recombination. This assay measures crossing over along the entire length of chromosome III for the entire cell population. At various time points, cells were collected from SPM and chromosomes were subjected to pulsed-field electrophoresis followed by Southern blot analysis probing for chromosome III (A–C). A single crossover between the parental circular and linear chromosome III homologs is detected as a band that is twice the molecular weight of the parental linear chromosome III. A (three-stranded) double crossover is detected as a band that is three times the molecular weight. The parental circular chromosome does not enter the gel and is therefore not detected (see materials and methods). The bottom band represents parental linear chromosome III and the middle and top bands represent single-crossover (single CO) and double-crossover (double CO) products, respectively. (A) Assay of wild type (NMY268), zip1Δ (NMY270), and zip1-4LA (NMY272) strains; (B) the same assay performed in a swe1 background (NMY471, NMY473, NMY472); (C) the same assay performed in a pch2 background (NMY671, NMY672, NMY673). (D–F) For each blot on the left, the total signal in the two recombinant bands was calculated as a percentage of the total signal in all three bands and plotted as a function of time. (G) Histograms of the amount of crossing over of zip1Δ and zip1-4LA strains as a percentage of the corresponding ZIP1 control strains. For example, the bars labeled swe1 zip1Δ represent the level of crossing over in the swe1 zip1Δ strain expressed as a percentage of the swe1 ZIP1 control analyzed in the same experiment. Comparisons were made at all four meiotic time points (25, 40, 55, and 70 hr).

To determine the effect of the swe1 and pch2 mutations on recombination in zip1-4LA, crossing over was assayed in swe1 zip1-4LA and zip1-4LA pch2 double mutants and compared to the swe1 and pch2 single mutants, respectively. The swe1 and pch2 single mutants exhibit high levels of spore viability (Leu and Roeder 1999; San-Segundo and Roeder 1999), suggesting that these mutants undergo wild-type levels of crossing over. The swe1 zip1-4LA mutant exhibits a slight improvement in the kinetics of recombinant formation, but the final level of crossover products is still only ∼54% of the ZIP1 control (i.e., the swe1 single mutant) (Figure 6, B, E, and G). In contrast, crossing over in the pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant occurs with normal kinetics and approximately at the pch2 level (89% of pch2 at 70 hr). These results are compatible with the spore viability data in Figure 5B. The swe1 zip1-4LA double mutant displays reduced spore viability (compared to swe1 alone), consistent with the observed reduction in crossing over. However, the pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant displays nearly wild-type levels of spore viability, as expected for wild-type levels of crossing over.

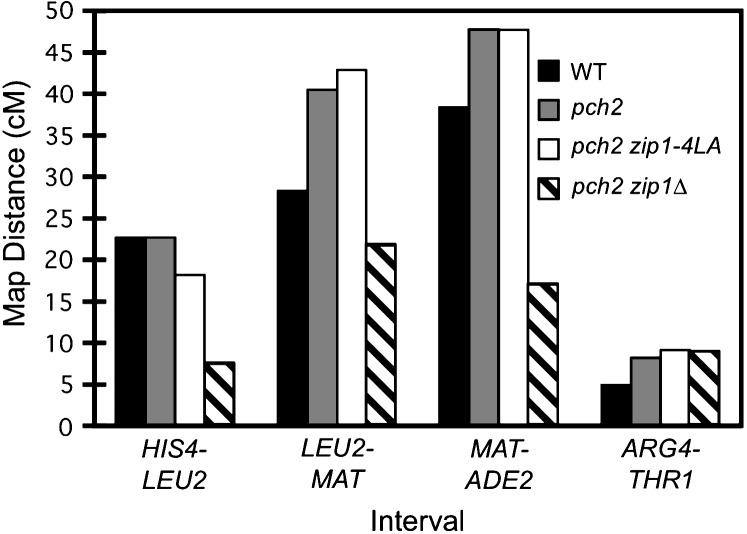

The pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant was also characterized for crossing over by tetrad analysis (Figure 7). Four intervals were assayed, three on chromosome III and one on chromosome VIII. The pch2 zip1-4LA strain exhibits levels of crossing over similar to pch2 in all intervals, consistent with the results of the physical crossover assay. Thus, zip1-4LA is proficient in crossing over in a pch2 background.

Figure 7.—

Tetrad analysis of pch2 zip1-4LA strains. Shown is the map distance (centimorgans) in three intervals on chromosome III and in one interval on chromosome VIII for wild-type (NMY650), pch2 (NMY654), pch2 zip1-4LA (NMY661), and pch2 zip1Δ (NMY664) strains in the BR1919-8B diploid background. Using the G-test of homogeneity, there is no statistically significant difference between map distances in pch2 and pch2 zip1-4LA for any interval: P = 0.460 for HIS4-LEU2; P = 0.617 for LEU2-MAT; P = 0.843 for MAT-ADE2; P = 0.884 for ARG4-THR1.

Either L657A or L664A is sufficient for meiotic arrest:

To determine which of the amino acid substitutions in zip1-4LA are required for causing cell cycle arrest, individual amino acid substitutions L643A, L650A, L657A, and L664A were created. These ZIP1 mutations were constructed in a centromere-containing plasmid and introduced into a BR2495 strain background in which the chromosomal ZIP1 gene is deleted. The phenotypes of the four individual leucine-to-alanine substitutions are not identical with respect to sporulation. Both zip1-L643A and zip1-L650A are able to sporulate well, whereas both zip1-L657A and zip1-L664A are completely unable to sporulate (data not shown). Therefore, a single leucine-to-alanine substitution at either L657 or L664 is sufficient to cause meiotic cell cycle arrest.

DISCUSSION

zip1-4LA is a novel nonnull allele:

The zip1Δ mutation leads to a complete failure of SC formation and causes meiotic cell cycle arrest in midmeiotic prophase. In contrast, the zip1-4LA mutant makes an apparently normal SC (Figure 2B) with wild-type kinetics (Figure 3B), but cells nevertheless undergo prophase arrest. Given the level of the resolution of fluorescence microscopy, we cannot rule out the possibility of minor disruptions in the SC (i.e., incomplete synapsis) in the zip1-4LA mutant. However, even mutants with only modest defects in SC formation exhibit polycomplex formation (e.g., msh4; Novak et al. 2001), which zip1-4LA does not, arguing that both the rate and extent of synapsis are normal in the zip1-4LA mutant. We also cannot exclude the possibility that one or a few chromosomes are engaged in nonhomologous synapsis in the zip1-4LA mutant. Extensive nonhomologous synapsis (e.g., in hop2; Leu et al. 1998) leads to delayed synapsis, polycomplex formation, branching networks of chromosomes, and an inability to separate chromosome pairs during spreading; none of these situations applies to the zip1-4LA mutant. Note that homologs pair normally in the zip1 null mutant (Nag et al. 1995).

The zip1-4LA mutant is similar in phenotype to two deletion mutants characterized previously by Tung and Roeder (1998)—zip1-M2 and zip1-MC1. These mutants also fail to sporulate in the BR2495 background, but they do make SCs. Both of these mutations remove ∼300 amino acids from the Zip1 coiled coil (Figure 1A), and they lead to the formation of abnormally narrow SCs, as observed by electron microscopy (Tung and Roeder 1998). It was postulated that the drastic change in the width of the SC is responsible for the arrest in prophase; however, the behavior of the zip1-4LA mutant argues against this explanation. Of the many coiled-coil deletion mutants generated in this study, only those that remove the four leucine residues affected by the zip1-4LA mutation fail to sporulate. Thus, this region appears to play an especially important role in promoting or regulating cell cycle progression.

Meiotic cell cycle arrest in zip1-4LA strains is tighter than in any of the coiled-coil deletion mutants. zip1-4LA fails to sporulate in the BR1919-8B background, whereas sporulation occurs at low levels (∼2–5%) in mutants in which the 4LA region is deleted, including zip1-M2, zip1-MC1, zip1-ΔD, zip1-ΔE, zip1-ΔJ, and zip1Δ. (Sporulation was assessed in strains in which the wild-type ZIP1 gene was replaced by the zip1 deletion mutation.) In the SK1 strain background, zip1-4LA does sporulate, but the efficiency is reduced compared to the null mutant. The severity of the zip1-4LA phenotype, with respect to sporulation, is surprising given the subtle nature of this mutation. The four amino acid changes are all conservative substitutions (leucine to alanine), and they do not affect the predicted ability of the Zip1 protein to form a coiled coil (as determined by Macstripe 2.0, a program based on an algorithm by Lupas et al. 1991). Yet the presence of the Zip1-4LA protein has a more deleterious effect on sporulation than the complete absence of Zip1 protein or the presence of Zip1 protein with a dramatically shortened coiled coil.

zip1-4LA undergoes checkpoint-induced cell cycle arrest:

A number of observations indicate that meiotic arrest in the zip1-4LA mutant is mediated by a cell cycle checkpoint triggered by a defect in meiotic recombination and/or chromosome synapsis. First, the sporulation defect of zip1-4LA is suppressed by a spo11 mutation, which prevents double-strand break formation and the initiation of SC formation (Giroux et al. 1989; Loidl et al. 1994). Second, the zip1-4LA sporulation defect is suppressed by mutations in the DDC1, MEC3, and RAD17 genes (Figure 4), whose products are involved in sensing unrepaired double-strand breaks (reviewed by Zhou and Elledge 2000). Finally, the zip1-4LA sporulation defect is partially suppressed by deletion of the SWE1 gene (Figure 5), whose product acts downstream of Ddc1/Med3/Rad17 in the meiotic checkpoint pathway (reviewed by Bailis and Roeder 2000). In every case, however, spore viability in the double mutant (e.g., ddc1 zip1-4LA or swe1 zip1-4LA) is reduced compared to that in the corresponding single mutant (e.g., ddc1 or swe1), implying that the zip1-4LA mutation confers a defect in double-strand break repair and/or chromosome segregation even when the checkpoint is bypassed. Consistent with this interpretation, physical analysis of recombination demonstrates that crossing over occurs at only ∼54% of the swe1 level in the zip1-4LA swe1 double mutant (Figure 6G).

The sporulation defect of zip1-4LA is also suppressed by the absence of the meiosis-specific checkpoint protein Pch2 (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999). In this case, both sporulation and spore viability are restored approximately to pch2 (i.e., wild-type) levels (Figure 5). Furthermore, meiotic recombination occurs at normal levels in the pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant, as evidenced in both genetic and physical assays (Figures 6 and 7). The behavior of the pch2 zip1-4LA double mutant provides additional evidence that prophase arrest in zip1-4LA strains is mediated by a meiotic checkpoint and suggests a special relationship between Pch2 and Zip1, as discussed further below.

Why does the zip1-4LA mutant arrest in prophase?

What is the nature of the defect that triggers cell cycle arrest in zip1-4LA strains? There are at least three possibilities. First, arrest might be triggered by unrepaired double-strand breaks or some other recombination intermediate. Second, the zip1-4LA mutant might be defective in SC disassembly, and cell cycle progression might be blocked as long as the SC persists. Third, the checkpoint might be activated by an aberration in SC structure caused by the zip1-4LA mutation.

A physical assay demonstrates that the production of crossover products is delayed, and the final level of crossover products is reduced, in the zip1-4LA single mutant (Figure 6, A and B). This observation raises the possibility that the checkpoint is activated by recombination intermediates, such as unrepaired double-strand breaks. Previous studies suggested that the Zip1 protein plays a role in recombination (Storlazzi et al. 1996), and this function may be impaired by the zip1-4LA mutation. Arguing against this possibility, however, is the observation that the pch2 zip1-4LA mutant undergoes normal levels of crossing over with the same kinetics as wild type (Figure 6, C, F, and G). This result suggests that zip1-4LA is not deficient in recombination per se and argues that the decrease in recombination is an indirect consequence of cell cycle arrest. The mutant might arrest at a stage in the cell cycle prior to the point at which recombination intermediates are normally resolved.

In wild type, the SC disassembles prior to formation of the metaphase I spindle (Padmore et al. 1991). Perhaps SC containing the Zip1-4LA protein is unable to disassemble, and persistence of the SC is the cause (rather than the consequence) of cell cycle arrest at pachytene. Attempting chromosome segregation with some or all pairs of homologs still held together by SC would lead to defects in chromosome segregation and might account for the reduced spore viability observed in the swe1 zip1-4LA double mutant. To investigate this possibility, meiosis I nuclei from swe1 and swe1 zip1-4LA cells were examined for staining with Zip1 antibodies. None of the nuclei with spindles (identified by tubulin staining) exhibited any Zip1 staining (data not shown), arguing against a defect in SC disassembly. Meiosis I nuclei from zip1-4LA pch2 cells also do not exhibit Zip1 staining, consistent with the high spore viability observed in this strain.

The presence of the Zip1-4LA protein might alter the structure of the SC, and this aberration may be detected by a surveillance mechanism that monitors SC morphology. Perhaps the region defined by the zip1-4LA mutation is involved in interacting with another protein, possibly another component of the SC central region. In mutants in which the zip1-4LA region is deleted, this protein might be absent from the SC, whereas this protein might be present in an aberrant configuration in the zip1-4LA mutant. This difference might explain the difference in the severity of cell cycle arrest in the deletion mutants vs. zip1-4LA.

The observation that zip1-L657A and zip1-L664A are completely unable to sporulate, while zip1-L643A and zip1-L650A are able to sporulate well, demonstrates that the phenotype of zip1-4LA is specific to certain residues in the 4LA region. Equilibrium and kinetic circular dichroism studies of the Gcn4 leucine zipper have indicated that the third and fourth heptad repeats in the zipper are the heptads that drive leucine zipper formation (Zitzewitz et al. 2000). Thus, the observation that L657A and L664A (in the third and fourth heptads) cause a sporulation defect suggests that the zip1-4LA mutation perturbs the Zip1 dimer interaction. Although the Zip1 dimer might be perturbed locally in the 4LA region, it is unlikely that the Zip1-4LA protein completely fails to dimerize because the four heptads affected by the zip1-4LA mutation are embedded in a very long coiled-coil region consisting of ∼80 heptad repeats. Furthermore, a Zip1 protein that failed to dimerize would almost certainly not support SC formation.

A previous study (Dong and Roeder 2000) showed that two Zip1 dimers lie head to head to span the width of the SC, with the carboxy termini of Zip1 associated with lateral elements and the amino termini located near the middle of the central region. On the basis of the analysis of Zip1 deletion mutants (Tung and Roeder 1998), it was suggested that Zip1 dimers attached to opposing lateral elements overlap in the amino-terminal portion of the coiled coil. The Zip1-4LA mutation is located close to the carboxy terminus of the Zip1 coiled coil and therefore is not expected to affect the interaction between Zip1 dimers.

zip1-4LA may trigger a Pch2-dependent synapsis checkpoint:

The PCH2 gene was originally identified in a screen for mutations that allow the zip1Δ mutant to sporulate (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999). Unlike the ddc1/mec3/rad17 mutations, pch2 does not fully suppress the sporulation defect of mutants defective in the enzymology of recombination, such as dmc1 or hop2 (San-Segundo and Roeder 1999; Zierhut et al. 2004; Hochwagen et al. 2005). Thus, Pch2 may monitor processes or structures distinct from recombination.

Recently, Wu and Burgess (2006) showed that the Pch2 and Rad17 proteins act independently to negatively regulate meiotic cell cycle progression. In addition, they presented evidence that the Zip1 protein is required for Pch2-mediated inhibition of cell cycle progression. They argued that the presence of incomplete or aberrant SC activates a synapsis checkpoint whose function depends on Pch2. Consistent with this hypothesis, Pch2 orthologs are present in organisms known to make SCs, but absent from eukaryotes in which meiotic chromosomes do not undergo synapsis (Wu and Burgess 2006).

Compelling evidence that Pch2 acts in a checkpoint that monitors synapsis comes from studies in C. elegans, in which SC assembly occurs independently of recombination (Bhalla and Dernburg 2005). In this organism, chromosome pairing and synapsis initiate at cis-acting loci called pairing centers (MacQueen et al. 2005); these centers are present at one end of each chromosome pair (Wicky and Ross 1996). Bhalla and Dernburg (2005) showed that in strains hemizygous for the X chromosome pairing center, the X chromosomes often fail to synapse and consequently fail to cross over. Furthermore, they observed a correlation between the frequency of asynaptic X chromosomes and the frequency of meiotic cells undergoing apoptosis. This programmed cell death is Pch2 dependent, suggesting that Pch2 plays a role in preventing cells with asynaptic chromosomes from completing gametogenesis. The Pch2-dependent cell death that occurs in pairing-center hemizygotes is independent of genes whose products act in the meiotic recombination checkpoint pathway.

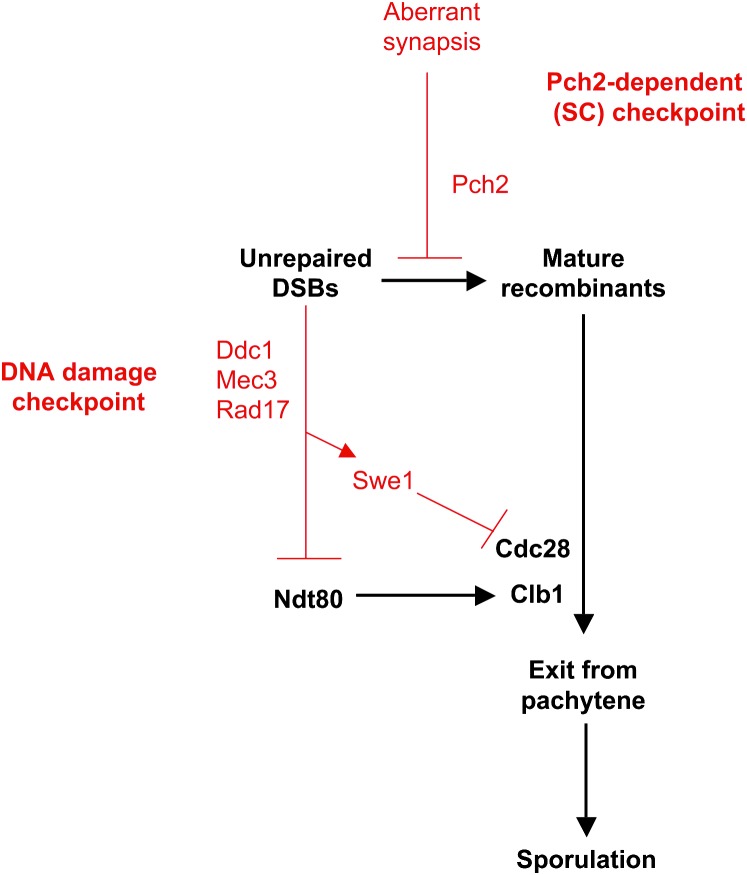

Model for Pch2-mediated arrest of zip1-4LA:

The recent evidence that Pch2 acts in an SC checkpoint pathway supports our hypothesis that cell cycle arrest in zip-4LA is due to formation of an SC that is recognized as aberrant. But if SC structure is the primary defect in zip1-4LA, then why is the sporulation defect alleviated by the ddc1/mec3/rad17 family of mutations? One possibility is that Pch2 functions to ensure the proper coupling between SC morphogenesis and meiotic recombination (Figure 8). In response to the zip1-4LA-induced perturbation in SC structure, Pch2 may block late steps in recombination, either by inhibiting recombination per se or by blocking cell cycle progression. The accumulation of recombination intermediates would then trigger the recombination checkpoint, mediated by the Ddc1/Mec3/Rad17 proteins in conjunction with other players. According to this model, Pch2 acts upstream of Ddc1/Mec3/Rad17 in the checkpoint pathway, and the defect in recombination is a consequence of Pch2's response to the perturbation in SC structure.

Figure 8.—

Model of the relationship between SC and DNA damage checkpoints. Proteins and events involved in normal cell cycle progression are indicated in black; proteins and events involved in checkpoint-induced cell cycle arrest are depicted in red. Pch2 might function to ensure proper coupling between SC morphogenesis and meiotic recombination. A signal from aberrant SC could signal Pch2 to inhibit late steps in recombination, either by preventing the completion of recombination or by blocking progression to the stage in the cell cycle when recombination normally is completed. Accumulation of recombination intermediates would then trigger the DNA damage checkpoint, dependent on Ddc1/Mec3/Rad17. Wu and Burgess (2006) have shown that almost all of the spores produced by a pch2 rad17 double mutant are inviable, suggesting that Pch2 and/or Rad17 have additional unknown functions.

Acknowledgments

We thank previous and current members of the Roeder lab for helpful comments on the manuscript and for their support and encouragement. N.M. thanks H. Tsubouchi for many helpful discussions and for technical support. Oligonucleotide synthesis and DNA sequencing were performed by the W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory at Yale University. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM28904 (to G.S.R.) and by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References

- Agarwal, S., and G. S. Roeder, 2000. Zip3 provides a link between recombination enzymes and synaptonemal complex proteins. Cell 102 245–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alani, E., L. Cao and N. Kleckner, 1987. A method for gene disruption that allows repeated use of URA3 selection in the construction of multiply disrupted yeast strains. Genetics 116 541–545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alber, T., 1992. Structure of the leucine zipper. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2 205–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allers, T., and M. Lichten, 2001. Differential timing and control of noncrossover and crossover recombination during meiosis. Cell 106 47–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailis, J. M., and G. S. Roeder, 2000. The pachytene checkpoint. Trends Genet. 16 395–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, K. R., C. Zhang, K. M. Shokat and I. Herskowitz, 2003. Control of landmark events in meiosis by the CDK Cdc28 and the meiosis-specific kinase Ime2. Genes Dev. 17 1524–1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhalla, N., and A. F. Dernburg, 2005. A conserved checkpoint monitors meiotic chromosome synapsis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Science 310 1683–1686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bishop, D. K., D. Park, L. Xu and N. Kleckner, 1992. DMC1: a meiosis-specific yeast homolog of E. coli recA required for recombination, synaptonemal complex formation, and cell cycle progression. Cell 69 439–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boeke, J. D., F. Lacroute and G. R. Fink, 1984. A positive selection for mutants lacking orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase activity in yeast: 5-fluoro-orotic acid resistance. Mol. Gen. Genet. 197 345–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booher, R. N., R. J. Deshaies and M. W. Kirschner, 1993. Properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae wee1 and its differential regulation of p34CDC28 in response to G1 and G2 cyclins. EMBO J. 12 3417–3426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chu, S., and I. Herskowitz, 1998. Gametogenesis in yeast is regulated by a transcriptional cascade dependent on Ndt80. Mol. Cell 1 685–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chua, P. R., and G. S. Roeder, 1998. Zip2, a meiosis-specific protein required for the initiation of chromosome synapsis. Cell 93 349–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong, H., and G. S. Roeder, 2000. Organization of the yeast Zip1 protein within the central region of the synaptonemal complex. J. Cell Biol. 148 417–426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dresser, M. E., and C. N. Giroux, 1988. Meiotic chromosome behavior in spread preparations of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 106 567–578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engebrecht, J., and G. S. Roeder, 1989. Yeast mer1 mutants display reduced levels of meiotic recombination. Genetics 121 237–247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, R. E., M. Dresser and M. Breitenbach, 1991. Identifying sporulation genes, visualizing synaptonemal complexes, and large-scale spore and spore wall purification. Methods Enzymol. 194 110–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fung, J. C., B. Rockmill, M. Odell and G. S. Roeder, 2004. Imposition of crossover interference through the nonrandom distribution of synapsis initiation complexes. Cell 116 795–802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Game, J. C., K. C. Sitney, V. E. Cook and R. K. Mortimer, 1989. Use of a ring chromosome and pulsed-field gels to study interhomolog recombination, double-strand DNA breaks and sister-chromatid exchange in yeast. Genetics 123 695–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroux, C. N., M. E. Dresser and H. F. Tiano, 1989. Genetic control of chromosome synapsis in yeast meiosis. Genome 31 88–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein, A. L., and J. H. McCusker, 1999. Three new dominant drug resistance cassettes for gene disruption in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 15 1541–1553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hepworth, S. R., H. Friesen and J. Segall, 1998. NDT80 and the meiotic recombination checkpoint regulate expression of middle sporulation-specific genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 18 5750–5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S. N., H. D. Hunt, R. M. Horton, J. K. Pullen and L. R. Pease, 1989. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene 77 51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochwagen, A., W.-H. Tham, G. A. Brar and A. Amon, 2005. The FK506 binding protein Fpr3 counteracts protein phosphatase 1 to maintain meiotic recombination checkpoint activity. Cell 122 861–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, E. E., and G. S. Roeder, 2002. A role for Ddc1 in signaling meiotic double-strand breaks at the pachytene checkpoint. Genes Dev. 16 363–376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keeney, S., 2001. Mechanism and control of meiotic recombination initiation. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 52 1–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landschulz, W. H., P. F. Johnson and S. L. McKnight, 1988. The leucine zipper: a hypothetical structure common to a new class of DNA binding proteins. Science 240 1759–1764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu, J.-Y., and G. S. Roeder, 1999. The pachytene checkpoint in S. cerevisiae depends on Swe1-mediated phosphorylation of the cyclin-dependent kinase Cdc28. Mol. Cell 4 805–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leu, J.-Y., P. R. Chua and G. S. Roeder, 1998. The meiosis-specific Hop2 protein of S. cerevisiae ensures synapsis between homologous chromosomes. Cell 94 375–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loidl, J., F. Klein and H. Scherthan, 1994. Homologous pairing is reduced but not abolished in asynaptic mutants of yeast. J. Cell Biol. 125 1191–1200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longhese, M. P., R. Fraschini, P. Plevani and G. Lucchini, 1996. Yeast pip3/mec3 mutants fail to delay entry into S phase and to slow DNA replication in response to DNA damage, and they define a functional link between Mec3 and DNA primase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16 3235–3244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lupas, A., M. V. Dyke and J. Stock, 1991. Predicting coiled-coils from protein sequences. Science 252 1162–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall, D., and T. Weinert, 1997. G2/M checkpoint genes of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: further evidence for roles in DNA replication and/or repair. Mol. Gen. Genet. 256 638–651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydall, D., Y. Nikolsky, D. K. Bishop and T. Weinert, 1996. A meiotic recombination checkpoint controlled by mitotic checkpoint genes. Nature 383 840–843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacQueen, A. J., C. M. Phillips, N. Bhalla, P. Weiser, A. M. Villeneuve et al., 2005. Chromosome sites play dual roles to establish homologous synapsis during meiosis in C. elegans. Cell 123 1037–1050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nag, D. K., H. Scherthan, B. Rockmill, J. Bhargava and G. S. Roeder, 1995. Heteroduplex DNA formation and homolog pairing in yeast meiotic mutants. Genetics 141 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novak, J. E., P. Ross-Macdonald and G. S. Roeder, 2001. The budding yeast Msh4 protein functions in chromosome synapsis and the regulation of crossover distribution. Genetics 158 1013–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oldenburg, K. R., K. T. Vo, S. Michaelis and C. Paddon, 1997. Recombination-mediated PCR-directed plasmid construction in vivo in yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 25 451–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmore, R., L. Cao and N. Kleckner, 1991. Temporal comparison of recombination and synaptonemal complex formation during meiosis in S. cerevisiae. Cell 66 1239–1256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill, B., and G. S. Roeder, 1990. Meiosis in asynaptic yeast. Genetics 126 563–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockmill, B., M. Sym, H. Scherthan and G. S. Roeder, 1995. Roles for two RecA homologs in promoting meiotic chromosome synapsis. Genes Dev. 9 2684–2695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roeder, G. S., 1997. Meiotic chromosomes: it takes two to tango. Genes Dev. 11 2600–2621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San-Segundo, P., and G. S. Roeder, 1999. Pch2 links chromatin silencing to meiotic checkpoint control. Cell 97 313–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwacha, A., and N. Kleckner, 1994. Identification of joint molecules that form frequently between homologs but rarely between sister chromatids during yeast meiosis. Cell 76 51–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman, F., G. R. Fink and J. B. Hicks, 1986. Methods in Yeast Genetics: A Laboratory Manual. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- Shuster, E. O., and B. Byers, 1989. Pachytene arrest and other meiotic effects of the start mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 123 29–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sikorski, R., and P. Hieter, 1989. A system of shuttle vectors and yeast host strains designed for efficient manipulation of DNA in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 122 19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, A. V., and G. S. Roeder, 1997. The yeast Red1 protein localizes to the cores of meiotic chromosomes. J. Cell Biol. 136 957–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokal, R. R., and F. J. Rohlf, 1995. Biometry. W. H. Freeman, San Francisco/New York.

- Storlazzi, A., L. Xu, A. Schwacha and N. Kleckner, 1996. Synaptonemal complex (SC) component Zip1 plays a role in meiotic recombination independent of SC polymerization along the chromosomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93 9043–9048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym, M., and G. S. Roeder, 1994. Crossover interference is abolished in the absence of a synaptonemal complex protein. Cell 79 283–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym, M., and G. S. Roeder, 1995. Zip1-induced changes in synaptonemal complex structure and polycomplex assembly. J. Cell Biol. 128 455–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sym, M., J. Engebrecht and G. S. Roeder, 1993. Zip1 is a synaptonemal complex protein required for meiotic chromosome synapsis. Cell 72 365–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, D. A., and F. W. Stahl, 1999. Genetic control of recombination partner preference in yeast meiosis: isolation and characterization of mutants elevated for meiotic unequal sister-chromatid recombination. Genetics 153 621–641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi, T., and G. S. Roeder, 2005. A synaptonemal complex protein promotes homology-independent centromere coupling. Science 308 870–873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsubouchi, T., H. Zhao and G. S. Roeder, 2006. The meiosis-specific Zip4 protein regulates crossover distribution by promoting synaptonemal complex formation together with Zip2. Dev. Cell 10 809–819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung, K.-S., and G. S. Roeder, 1998. Meiotic chromosome morphology and behavior in zip1 mutants of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 149 817–832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung, K.-S., E. Hong and G. S. Roeder, 2000. The pachytene checkpoint prevents accumulation and phosphorylation of the meiosis-specific transcription factor Ndt80. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97 12187–12192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wach, A., A. Brachat, R. Pohlmann and P. Philippsen, 1994. New heterologous modules for classical or PCR-based gene disruptions in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast 10 1793–1808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H., S. Frackman, J. Kowalisyn, R. E. Esposito and R. Elder, 1987. Developmental regulation of SPO13, a gene required for separation of homologous chromosomes at meiosis I. Mol. Cell. Biol. 7 1425–1435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicky, C., and A. M. Ross, 1996. The role of chromosome ends during meiosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. BioEssays 18 447–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, H.-Y., and S. M. Burgess, 2006. Meiotic chromosome metabolism is monitored by two distinct prophase checkpoints in budding yeast. Curr. Biol. 16 2473–2479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., M. Ajimura, R. Padmore, C. Klein and N. Kleckner, 1995. NDT80, a meiosis-specific gene required for exit from pachytene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15 6572–6581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, L., B. M. Weiner and N. Kleckner, 1997. Meiotic cells monitor the status of the interhomolog recombination complex. Genes Dev. 11 106–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, B.-B. S., and S. J. Elledge, 2000. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature 408 433–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickler, D., and N. Kleckner, 1999. Meiotic chromosomes: integrating structure and function. Annu. Rev. Genet. 33 603–754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zierhut, C., M. Berlinger, C. Rupp, A. Shinohara and F. Klein, 2004. Mnd1 is required for meiotic interhomolog repair. Curr. Biol. 14 752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zitzewitz, J. A., B. Ibarra-Molero, D. R. Fishel, K. L. Terry and C. R. Matthews, 2000. Preformed secondary structure drives the association reaction of GCN4-p1, a model coiled-coil system. J. Mol. Biol. 296 1105–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]