Abstract

Background

Little is known about the population prevalence of sleep problems or whether the associations of sleep problems with role impairment are due to comorbid mental disorders.

Methods

The associations of four 12-month sleep problems (difficulty initiating or maintaining sleep, early morning awakening, nonrestorative sleep) with role impairment were analyzed in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication controlling 12-month DSM-IV anxiety, mood, impulse-control, and substance disorders. The WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview was used to assess sleep problems and DSM-IV disorders. The WHO Disability Schedule-II (WHO-DAS) was used to assess role impairment.

Results

Prevalence estimates of the separate sleep problems were in the range 16.4-25.0%, with 36.3% reporting at least one of the four. Mean 12-month duration was 24.4 weeks. All four problems were significantly comorbid with all the 12-month DMS-IV disorders assessed in the survey (median OR: 3.4; 25th-75th percentile: 2.8-3.9) and significantly related to role impairment. Relationships with role impairment generally remained significant after controlling comorbid mental disorders. Nonrestorative sleep was more strongly and consistently related to role impairment than were the other sleep problems.

Conclusions

The four sleep problems considered here are of public health significance because of their high prevalence and significant associations with role impairment.

Keywords: insomnia, nonrestorative sleep, epidemiology, comorbidity, NCS-R, sleep

INTRODUCTION

DSM-IV defines insomnia as a syndrome characterized by problems in one or more of four sleep domains – difficulty initiating sleep (DIS), difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS), early morning awakening (EMA), and not feeling rested even after ample time in bed (nonrestorative sleep or NRS) -- associated with impairment in daytime functioning. General population surveys consistently find that roughly one-third of the US adult population report sleep problems (Ancoli-Israel and Roth 1999; Grandner and Kripke 2004; National Sleep Foundation 2005) and that 10-15% of the population meet DSM-IV criteria for insomnia (Breslau et al 1996; Cirignotta et al 1985; Costa e Silva et al 1996; Ohayon 1996; Ohayon 1997; Ohayon 2002).

The impaired daytime functioning required for a DSM-IV diagnosis of insomnia has been documented across a wide range of role functioning domains (Leger et al 2001) with a severity distribution comparable to that of many chronic physical disorders (Katz and McHorney 2002). Given the high prevalence of insomnia, this impairment could have considerable public health significance if it was known to be due to insomnia rather than to comorbid conditions. As insomnia is strongly comorbid with a number of mental disorders (Breslau et al 1996; Ford and Kamerow 1989), though, it is possible that the latter explain the impairment associated with insomnia. The current report addresses this issue by analyzing data from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R; Kessler and Merikangas 2004).

METHODS

Sample

The NCS-R is a nationally representative, face-to-face household survey of adults (ages 18+) based on a multi-stage clustered area probability sampling design (Kessler et al 2004c). A total of 9282 respondents participated in the survey (February 2001 - December 2003). The response rate was 70.9 %. Participants received a $50 honorarium. After complete description of the study to potential respondents, verbal informed consent was obtained. Consent was verbal rather than written in order to be consistent with the recruitment procedures used in the baseline NCS (Kessler et al 1994). The Human Subjects Committees of Harvard Medical School and the University of Michigan both approved these procedures.

All NCS-R respondents completed a Part I diagnostic interview using the WHO Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI 3.0; Kessler and Ustun 2004). A probability sub-sample of 5692 Part I respondents, which consisted of all Part I respondents with any DSMIV CIDI diagnosis (see below) and a probability sub-sample of those with no such diagnosis, also received a Part II interview that assessed additional disorders and correlates. Sleep problems were assessed in Part II. The Part II sample was weighted for differential probabilities of selection within households, differential recruitment intensity, over-sampling of Part I respondents with disorders into Part II, and residual discrepancies with the 2000 Census on socio-demographic and geographic variables. More complete information on NCS-R sampling and weighting is reported elsewhere (Kessler et al 2004c).

Sleep problems

Part II NCS-R respondents were asked yes-no questions about whether they had each of the three classic forms of sleep disturbance specified in the DSM-IV in the year before interview. The questions asked about “periods lasting two weeks or longer in the past 12 months” when the respondent experienced (1) difficulty initiating sleep (DIS; “nearly every night it took you two hours or longer before you could fall asleep”), (2) difficulty maintaining sleep (DMS; “you woke up nearly every night and took an hour or more to get back to sleep”), and (3) early morning awakening (EMA; “you woke up nearly every morning at least two hours earlier than you wanted to”). (Italics indicate emphasis in the original questions.) Nonrestorative sleep (NRS), in comparison, was assessed with a scale based on responses to four questions about frequency of having difficulties getting up in the morning, waking up not feeling rested, feeling as if they had not slept long enough even after having enough time in bed, and not feeling refreshed after sleep in the past 12 months. Response options were often, sometimes, rarely, and never (0-3). Principal axis factor analysis documented a clear one-factor structure, with factor loadings in the range .79-.86. A summary factor-based scale with a range of 0-12 was creating by summing responses to the four items. A dichotomous cut-point on this scale was selected to define a clinical threshold for nonrestorative sleep by carrying out regression analyses with each of the logically possible dichotomizations of the scale (e.g., 0 vs. 1-12, 0-1 vs. 2-12, …, 0-11 vs. 12) to predict the five measures of role impairment described below and setting the clinical threshold at the cut point that maximized explained variance. (Results available on request.)

Comorbid DSM-IV disorders

Core DSM-IV/CIDI disorders assessed in the NCS-R include anxiety disorders (panic disorder with or without agoraphobia, agoraphobia without panic disorder, specific phobia, social phobia, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety disorder), mood disorders (major depressive disorder, dysthymia, bipolar disorder I or II), impulse-control disorders (intermittent explosive disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, oppositional-defiant disorder, conduct disorder), and substance use disorders (alcohol and illicit drug abuse and dependence with abuse). Organic exclusion rules and diagnostic hierarchy rules were used in making diagnoses. As detailed elsewhere (Kessler et al 2004a; Kessler et al 2005), blinded clinical re-interviews using the non-patient version of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID; First et al 2002) with a probability sub-sample of NCS-R respondents found generally good concordance between DSM-IV diagnoses of anxiety, mood, and substance disorders based on the CIDI and the clinical assessments. Impulse-control disorder diagnoses were not validated, as the SCID clinical reappraisal interviews did not include an assessment of these disorders.

Role impairment

Role impairment was assessed with five measures. The first four were taken from the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule-II (WHO-DAS; Chwastiak and Von Korff 2003). These asked respondents to report the number of days out of the past 30 when they had each of the following experiences: totally unable to work or carry out their normal daily activities (days out of role); able to carry out their normal activities but had to cut down on what they did or not get as much done as usual (reduced quantity); cut back on the quality of your work or how carefully you worked (reduced quality); and needed to make an extreme effort to perform up to your usual in carrying out their normal daily activities (extreme effort). Each of the four responses is in the range 0-30 days.

The fifth measure of role impairment was based on responses to five questions about the frequency of daytime sleepiness assessed in conjunction with the assessment of nonrestorative sleep. The daytime sleepiness questions asked about falling asleep while watching TV or listening to the radio or reading, getting drowsy within ten minutes of sitting down, dozing off while relaxing, falling asleep during conversations or while visiting friends, and feeling fatigued during the day because of poor sleep. As with the assessment of nonrestorative sleep, response options were often, sometimes, rarely, and never. Principal axis factor analysis documented a clear one-factor structure (factor loadings in the range .78-.87). A summary factor-based scale was creating by summing responses to the individual items and transformed to a theoretical range of 0-100 for ease of interpretation. The highest score (100) was assigned to respondents who reported often having all five indicators of daytime sleepiness, while the lowest score (0) was assigned to respondents who reported never having any of these experiences.

Socio-demographic controls

Socio-demographic control variables included gender, age (18-29, 30-44, 45-59, 60+), race-ethnicity (Non-Hispanic White, Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, Other), education (less than high school graduation, high school, some post high school education without a college degree, and college degree or more), marital status (married-cohabiting, never married, separated-divorced, widowed), employment status (employed or self-employed, student, homemaker, retired, other), family income (in quartiles of the population distribution), and number of pre-school children (0, 1, 2+).

Analysis methods

Odds-ratios (ORs) and tetrachoric correlations were used to examine associations among the four dichotomous measures of sleep problems. Associations with socio-demographics and comorbid disorders were examined using logistic regression analysis in which the four sleep problems were treated as dichotomous outcomes. Logistic regression coefficients and their standard errors were exponentiated and are presented as ORs with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Associations with role impairment were estimated using linear regression analysis in which sleep problems were treated as predictors, controlling for socio-demographics and for comorbid DSM-IV disorders. Unstandardized regression coefficients and their standard errors are presented.

The recall periods of the sleep measures (the past twelve months) and the WHO-DAS measures of role impairment (number of impairment days in the past thirty days) differed based on the assumption that sleep problems can be recalled over a longer time period than can information about number of impairment days. As a result of this problem, estimates of effect size for these outcomes should be interpreted as average monthly effects of annual sleep problems, which are presumably lower than effects of current sleep problems on currently functioning. We have no way to generate estimates of the latter effects with the NCS-R data.

As the NCS-R sample design featured clustering and weighting to adjust for differential probabilities of selection, significance tests based on the assumption of simple random sampling are inappropriate. We consequently calculated standard errors of estimates using the design-based Taylor series linearization method (Wolter 1985) implemented in the SUDAAN software system (Research Triangle Institute 2002). The significance of set of coefficients was assessed with design-corrected Wald χ2 tests. Significance was consistently evaluated using two-sided .05-level design-based tests.

RESULTS

Prevalence, inter-correlations and duration

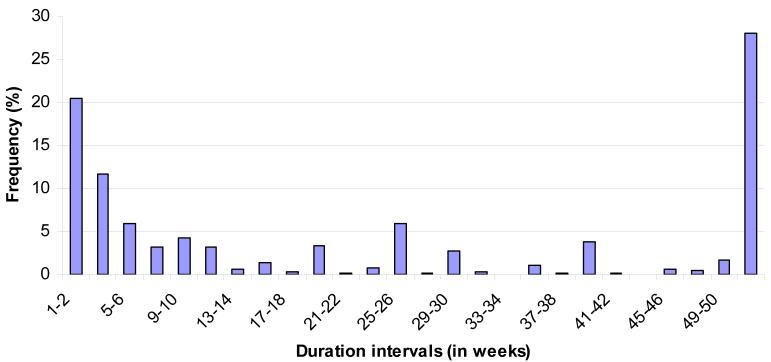

Twelve-month prevalence estimates are 16.4% for DIS, 19.9% for DMS, 16.7% for EMA, and 25.0% for NRS. (Table 1) The proportion of the sample with one or more of these four problems is 36.3%. The fact that the latter proportion is much less than the sum of the four problem-specific proportions (which would be the prevalence of having any of the four if no single individual had more than one sleep problem) indirectly indicates that the four problems are strongly interrelated. This can be seen more directly in the fact that the tetrachoric correlations among pairs of problems are quite high (.65-.76). Mean duration in the twelve months before interview was 22.4 weeks among respondents who reported any of the four problems and in the range 25.2-28.7 weeks among respondents for individual problems. The mean is somewhat deceptive, though, as duration shows a bimodal distribution in which one-third of respondents with any of the problems (32.1%) reported a short duration (2-4 weeks), 28.0% reported persistence throughout the year, and the remainder reporting intermediate durations. (Figure 1)

Table 1.

Prevalence, inter-correlations, and mean duration (weeks in the past year) of 12-month sleep problems in the Part II NCS-R (n=5692)

| Inter-correlations1 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | DIS | DMS | EMA | NRS | Duration | ||||

| % | (se) | OR | OR | OR | OR | Mean | (se) | (n) | |

| Difficulty Initiating Sleep (DIS) | 16.4 | (0.6) | -- | -- | -- | -- | 28.7 | (0.9) | (1191) |

| Difficulty Maintaining Sleep (DMS) | 19.9 | (0.8) | 0.76* | -- | -- | -- | 28.7 | (0.7) | (1436) |

| Early Morning Awakening (EMA) | 16.7 | (0.7) | 0.66* | 0.84* | -- | -- | 28.1 | (0.9) | (1203) |

| Non-Restorative Sleep (NRS) | 25.0 | (0.8) | 0.68* | 0.70* | 0.65* | -- | 25.2 | (0.8) | (1901) |

| Any | 36.3 | (1.0) | 24.4 | (0.7) | (2578) | ||||

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test.

Tetrachoric correlations

Figure 1.

Duration of sleep problems (in weeks) over the past year among respondents with 12-month sleep problems in the Part II NCS-R (n=2578)

Although the four sleep problems are strongly inter-correlated, all logically possible combinations exist among them. (Table 2) These combinations were examined by distinguishing the three classic sleep problems (DIS, DMS, and EMA) from NRS, as the latter is a problem with sleepiness while awake rather than a problem with being unable to sleep. A higher proportion of the sample reported only one of the three classic sleep problems (12.8%) than either two (9.0%) or all three (7.4%). While the conditional probability of nonrestorative sleep was highest among respondents with all three of the classic sleep problems (73.4%), lower among those with two (59.2-66.4%) or one (50.2-55.7%) and lowest among those with none of the three (10.0%), nearly one-third of respondents with NRS reported not having any of the three classic sleep problems. Mean duration of sleep problems in the twelve months before interview was highest among respondents who reported all four sleep problems (34.5 weeks) and lowest among those who reported only one (11.2-24.8 weeks).

Table 2.

The multivariate associations and mean duration of 12-month sleep problem profiles in the Part II NCS-R

| Type of sleep problem |

Multivariate distribution of DIS, DMS and EMA |

Conditional prevalence of NRS |

Mean Duration | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NRS+ | NRS− | ||||||||

| % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | % | (se) | (n) | |

| I. Only one | |||||||||

| DIS | 4.7 | (0.4) | 55.7 | (4.1) | 24.0 | (2.6) | 24.8 | (3.7) | (284) |

| DMS | 4.5 | (0.3) | 53.7 | (3.3) | 24.1 | (2.6) | 20.9 | (2.6) | (302) |

| EMA | 3.6 | (0.3) | 50.2 | (4.4) | 18.9 | (3.1) | 11.2 | (1.7) | (231) |

| II. Exactly two | |||||||||

| DIS-DMS | 3.3 | (0.3) | 66.4 | (4.4) | 28.2 | (1.9) | 19.8 | (3.9) | (245) |

| DIS-EMA | 1.0 | (0.2) | 63.2 | (6.5) | 27.9 | (3.4) | 22.9 | (5.6) | (83) |

| DMS-EMA | 4.7 | (0.5) | 59.2 | (4.8) | 31.4 | (1.4) | 27.2 | (3.6) | (310) |

| III. Other | |||||||||

| None | 70.9 | (0.9) | 10.0 | (0.6) | 16.7 | (1.1) | -- | -- | (3658) |

| DIS-DMS-EMA | 7.4 | (0.4) | 73.4 | (1.9) | 34.5 | (1.4) | 29.5 | (3.1) | (579) |

Socio-demographic correlates

Socio-demographic correlates of sleep problems are generally modest in magnitude. (Results not reported, but available on request.) The most notable associations are with age. Age is inversely related to DIS and NRS (1.9-2.7 elevated odds among respondents ages 18-29 vs. 60+), while middle-aged respondents have the highest odds of DMS and EMA (1.3-1.7). Somewhat surprisingly, the number of young children in the home and family income are unrelated to any of the sleep problems.

Comorbidity with DSM-IV disorders

The four sleep problems are all significantly and positively related to each of the 12-month DMS-IV/CIDI disorders, resulting in roughly half (47.8-53.7) of respondents with the separate sleep problems meeting criteria for one or more of these disorders. (Table 3 about here) Odds-ratios of individual sleep problems with individual DSM disorders are in the range 1.6-6.1, with a median OR of 3.4 and an inter-quartile range (25th-75th percentiles) of 2.8-3.9. No consistent variation exists in magnitude of ORs either across the sleep problems for particular classes of DSM-IV disorders or across classes of these disorders for particular sleep problems. The only clear pattern of variation involves complexity of comorbidity, with respondents meeting criteria for three or more 12-month DSM-IV disorders also having much higher odds of sleep problems (ORs in the range 4.6-6.3 compared to respondents with no 12-month DSM-IV disorders) than respondents with either two 12-month DSM-IV disorders (ORs in the range 2.2-3.2) or pure DSM-IV disorders (ORs in the range 1.5-2.0).

Table 3.

Comorbidity of 12-month sleep problems with 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the NCS-R (n = 5692)1

| DIS | DMS | EMA | NRS | Any | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | % | OR | (95% CI) | |

| I. Anxiety disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Panic disorder | 7.5 | 3.4* | (2.5-4.7) | 7.2 | 4.0* | (3.0-5.2) | 7.1 | 3.4* | (2.3-4.9) | 7.0 | 4.1* | (3.0-5.5) | 6.0 | 5.6* | (4.2-7.5) |

| Agoraphobia without panic | 2.3 | 2.9* | (1.6-5.5) | 2.2 | 3.9* | (2.2-7.0) | 1.7 | 2.2* | (1.2-3.8) | 1.6 | 2.4* | (1.3-4.3) | 1.6 | 3.4* | (1.9-6.3) |

| Specific phobia | 17.3 | 2.4* | (2.0-3.0) | 16.8 | 2.5* | (2.1-3.1) | 17.2 | 2.5* | (2.1-3.0) | 18.3 | 3.2* | (2.7-3.8) | 15.4 | 3.0* | (2.5-3.6) |

| Social phobia | 16.9 | 3.5* | (3.0-4.1) | 14.4 | 3.1* | (2.6-3.8) | 15.2 | 3.3* | (2.7-4.0) | 14.9 | 3.4* | (2.8-4.0) | 12.5 | 3.4* | (2.8-4.2) |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 5.9 | 2.9* | (2.2-3.8) | 6.0 | 3.0* | (2.3-3.9) | 6.3 | 3.2* | (2.2-4.7) | 7.2 | 6.1* | (4.4-8.3) | 5.6 | 5.7* | (4.0-8.1) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 9.6 | 3.8* | (2.8-5.2) | 10.0 | 5.0* | (3.8-6.5) | 9.2 | 3.6* | (2.7-4.6) | 9.3 | 5.0* | (3.6-6.9) | 7.5 | 4.9* | (3.8-6.4) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 1.9 | 3.6* | (1.7-7.6) | 1.2 | 2.5* | (1.0-6.2) | 1.5 | 3.4* | (1.5-7.6) | 1.8 | 8.3* | (4.0-17.2) | 1.3 | 7.2* | (3.1-16.8) |

| Any anxiety disorder | 37.0 | 3.2* | (2.6-3.9) | 35.8 | 3.4* | (2.9-4.1) | 35.8 | 3.3* | (2.8-3.9) | 38.0 | 4.1* | (3.6-4.7) | 32.5 | 4.0* | (3.4-4.8) |

| II. Mood disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Major depressive disorder | 16.5 | 3.5* | (2.8-4.4) | 15.8 | 3.9* | (3.2-4.7) | 14.0 | 2.9* | (2.4-3.4) | 18.0 | 6.1* | (5.0-7.5) | 14.2 | 5.8* | (4.5-7.5) |

| Dysthymia | 4.9 | 5.4* | (3.2-9.0) | 4.3 | 4.9* | (2.8-8.6) | 3.8 | 3.2* | (1.8-5.7) | 3.5 | 3.8* | (2.5-5.9) | 3.1 | 5.2* | (3.5-7.8) |

| Bipolar I-II disorders | 7.8 | 3.8* | (2.6-5.4) | 6.6 | 4.0* | (2.9-5.4) | 7.0 | 3.7* | (2.8-4.9) | 6.2 | 3.5* | (2.6-4.7) | 5.2 | 3.7* | (2.7-5.1) |

| Any mood disorder | 24.9 | 4.0* | (3.2-5.1) | 22.9 | 4.4* | (3.7-5.2) | 21.2 | 3.3* | (2.7-4.1) | 24.4 | 5.6* | (4.6-6.6) | 19.7 | 5.4* | (4.4-6.7) |

| III. Impulse-control disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Intermittent explosive disorder | 4.1 | 1.6* | (1.1-2.5) | 4.1 | 2.0* | (1.4-2.9) | 4.0 | 1.9* | (1.3-2.9) | 4.5 | 2.2* | (1.4-3.3) | 4.1 | 2.4* | (1.7-3.4) |

| Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder | 10.1 | 3.8* | (2.8-5.1) | 10.3 | 3.8* | (2.6-5.7) | 12.6 | 5.3* | (3.7-7.8) | 8.6 | 4.2* | (3.1-5.8) | 7.8 | 4.3* | (2.9-6.4) |

| Conduct disorder or ODD | 4.7 | 2.8* | (1.5-5.4) | 4.6 | 3.3* | (1.8-5.9) | 5.3 | 3.6* | (1.9-6.9) | 3.6 | 2.8* | (1.6-4.8) | 3.4 | 2.8* | (1.4-5.6) |

| Any impulse-control disorder | 18.0 | 2.7* | (2.1-3.4) | 18.3 | 2.9* | (2.1-4.0) | 20.6 | 3.4* | (2.5-4.7) | 16.6 | 3.2* | (2.5-4.2) | 15.3 | 3.2* | (2.4-4.3) |

| IV. Substance use disorders | |||||||||||||||

| Alcohol abuse2 | 6.7 | 2.7* | (2.0-3.7) | 4.8 | 2.4* | (1.6-3.7) | 4.9 | 2.3* | (1.6-3.2) | 4.9 | 2.0* | (1.4-2.7) | 4.7 | 2.4* | (1.7-3.6) |

| Alcohol dependence with abuse | 4.3 | 5.0* | (3.4-7.5) | 3.4 | 4.7* | (2.6-8.5) | 3.2 | 3.7* | (2.3-5.8) | 2.8 | 2.8* | (1.7-4.8) | 2.7 | 4.9* | (2.8-8.5) |

| Drug abuse2 | 3.4 | 3.2* | (1.8-5.6) | 2.3 | 2.9* | (1.6-5.1) | 2.5 | 2.8* | (1.6-5.2) | 2.6 | 2.7* | (1.6-4.8) | 2.3 | 3.3* | (1.7-6.2) |

| Drug dependence with abuse | 1.2 | 3.5* | (1.5-8.4) | 0.8 | 3.1* | (1.3-7.8) | 1.0 | 3.7* | (1.7-8.3) | 0.8 | 2.5* | (1.2-5.2) | 0.8 | 4.2* | (1.8-10.2) |

| Any substance use disorder | 16.3 | 2.8* | (2.3-3.5) | 12.4 | 2.4* | (1.9-3.2) | 11.2 | 1.9* | (1.4-2.4) | 13.5 | 2.6* | (2.0-3.3) | 11.8 | 2.6* | (2.0-3.5) |

| V. Any disorder | |||||||||||||||

| Any disorder | 53.2 | 3.6* | (2.9-4.4) | 49.3 | 3.7* | (3.1-4.4) | 47.8 | 3.2* | (2.7-3.8) | 53.7 | 4.4* | (3.8-5.0) | 46.4 | 4.1* | (3.4-5.0) |

| Exactly one | 20.6 | 1.6* | (1.3-2.0) | 19.8 | 1.6* | (1.3-2.0) | 18.6 | 1.5* | (1.2-1.8) | 22.6 | 2.0* | (1.7-2.3) | 20.4 | 1.9* | (1.6-2.4) |

| Exactly two | 12.6 | 2.2* | (1.7-2.8) | 12.5 | 2.7* | (2.1-3.3) | 12.1 | 2.4* | (1.9-3.0) | 14.0 | 3.2* | (2.6-3.9) | 12.2 | 3.5* | (2.9-4.2) |

| Three or more | 20.0 | 5.4* | (4.6-6.4) | 17.0 | 5.3* | (4.3-6.6) | 17.0 | 4.6* | (3.7-5.7) | 17.1 | 6.3* | (5.2-7.6) | 13.8 | 6.9* | (5.5-8.7) |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Controlling for sex, age, race-ethnicity, education, marital status, occupation, poverty line, number of young, middle and old aged children

With or without dependence

Role impairment

The associations of sleep problems predicting role impairment were examined in three different linear regression models. The first (the gross effects model) used sleep problems to predict role impairment with controls for socio-demographic variables. The coefficients in this model can be interpreted as adjusted mean differences in values on the impairment scales among of respondents with the sleep problems versus those without the sleep problems. All 20 coefficients (i.e., a separate coefficient for each of four sleep problems predicting each of the five measures of role impairment) in this gross effects model are statistically significant at the .05 level. (Table 4) Coefficients to predict daytime sleepiness range from a low of 19.3 (associated with DIS) to a high of 34.4 (associated with NRS). If we think of these coefficients as representing causal effects in the 0-100 metric of the daytime sleepiness scale, the high end of the coefficient range is equivalent to changing people from “rarely” to “sometimes” feeling fatigued during the day because of sleep problems. Coefficients to predict number of days out of role in the past 30 days are easier to interpret because the metric of the outcome is intuitive. Coefficients range from 3.2 (associated with EMA) to 4.0 (associated with DIS) more days out of role in the past 30 days for people with sleep problems than people without sleep problems. Coefficients to predict number of days when respondents reported either reduced quantity or work, reduced quality of work, or extreme effort to complete work range between 1.0 days (EMA predicting days of reduced work quality) and 2.0 days (NRS predicting days of reduced work quantity and days of extreme effort).

Table 4.

Associations of 12-month sleep problems with 30-day role functioning in the NCS-R (n = 5692)1

| Outcomes | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daytime sleepiness |

Days out of role |

Quantity | Quality | Extreme effort | ||||||

| b | (se) | b | (se) | B | (se) | b | (se) | b | (se) | |

| A. DIS | ||||||||||

| Gross2 | 19.3* | (1.0) | 4.0* | (0.4) | 1.9* | (0.3) | 1.3* | (0.2) | 1.8* | (0.2) |

| Net2 | −1.2 | (1.2) | 2.0* | (0.5) | 0.8* | (0.3) | 0.6* | (0.3) | 0.7* | (0.3) |

| Pure2 | 10.4* | (2.9) | 1.8 | (1.2) | 1.6* | (0.8) | 1.0 | (0.7) | 1.7* | (0.8) |

| B. DMS | ||||||||||

| Gross2 | 24.0* | (1.1) | 3.6* | (0.3) | 1.7* | (0.2) | 1.2* | (0.1) | 1.6* | (0.2) |

| Net2 | 6.1* | (1.6) | 1.3* | (0.4) | 0.5 | (0.3) | 0.4* | (0.2) | 0.4 | (0.3) |

| Pure2 | 18.1* | (2.1) | −0.4 | (0.4) | 0.1 | (0.4) | −0.1 | (0.2) | −0.5* | (0.2) |

| C. EMA | ||||||||||

| Gross2 | 24.5* | (1.3) | 3.2* | (0.3) | 1.4* | (0.2) | 1.0* | (0.2) | 1.6* | (0.2) |

| Net2 | 7.3* | (1.3) | 0.6 | (0.4) | 0.1 | (0.3) | 0.0 | (0.3) | 0.4 | (0.2) |

| Pure2 | 12.4* | (2.6) | −0.5 | (0.6) | 0.1 | (0.6) | 0.4 | (0.6) | 0.0 | (0.3) |

| D. NRS | ||||||||||

| Gross2 | 34.4* | (1.0) | 3.7* | (0.3) | 2.0* | (0.3) | 1.4* | (0.1) | 2.0* | (0.2) |

| Net2 | 29.8* | (1.2) | 2.2* | (0.4) | 1.5* | (0.3) | 1.0* | (0.2) | 1.5* | (0.2) |

| Pure2 | 42.2* | (1.7) | 2.0* | (0.3) | 1.6* | (0.3) | 1.2* | (0.2) | 1.4* | (0.2) |

Significant at the .05 level, two-sided test

Controlling for sex, age, race-ethnicity, education, marital status, occupation, number of young children

Gross models include controls only for the socio-demographic variables listed in footnote 1. Net models additionally control for all the 12-month DSM-IV disorders included in Table 3. Pure models are estimated in the sub-sample of respondents who met criteria for none of the 12-month DSM-IV disorders.

The second linear regression model (the net effects model) added controls for all the DSM-IV disorders considered earlier to the gross effects model in order to control statistically for the effects of mental disorders. All 20 coefficients in this are lower than those in the gross effects model, although 13 of the 20 coefficients remain significant at the .05 level. The three coefficients that significantly predict daytime sleepiness are in the range 6.1-29.8 points on the 0-100 daytime sleepiness scale. The three coefficients that significantly predict days out of role are in the range 1.3-2.2 days. The seven coefficients that significantly predict days with reduced quantity or work, reduced quality of work, or extreme effort are in the range 0.4-1.5 days. NRS sleep is the only sleep problem that significantly predicts all five measures of role impairment, while DIS predicts four, DMS three, and EMA one.

The third linear regression model (the pure effects model) is identical to the net effects model with the exception that it was estimated in the subset of respondents who had none of the 12-month DSM-IV disorders considered here. This exclusion was made to prevent any confounding of the effects of sleep problems with the effects of the mental disorders assessed in the survey. Ten of the 20 coefficients in this pure effects model are positive and significant at the .05 level. As in the net effects model, NRS is the only sleep problem that significantly predicts all five measures of role impairment, while DIS predicts three, DMS one, and EMA one. The significant coefficients are generally lower than those in the gross effects model but higher than those in the net effects model. One negative coefficient is significant (DMS predicting days of extreme effort).

DISCUSSION

These results have to be interpreted with three limitations in mind. First, while duration of sleep problems was assessed over the past 12 months in order to study the extent to which these problems are persistent over the course of a year, concerns about recall bias in reports about days out of role and role functioning led us to assess impairment over the shorter recall period of the past 30 days. This lack of comparability in time frames is likely to have introduced a conservative bias into the estimated associations of sleep problems with role functioning. Second, both sleep problems and role impairment were assessed with self-report measures, rather than objective assessments, which might be contaminated by comorbid mental disorders. Although efforts were made to adjust for such bias through statistical methods, it would be useful to replicate the analysis in a dataset that included objective measures of sleep problems and role functioning. Third, we cannot exclude the possibility that unmeasured physical disorders account for the associations between sleep problems and role impairment. This third limitation is by far the most important of the three, as we know that sleep problems can be caused by a wide range of physical disorders and that the latter might have effects on role functioning by virtue of other pathways than sleep disruption. An examination of comorbid physical disorders that parallels our analysis of comorbid mental disorders would be needed to investigate this third limitation.

Within the context of these limitations, we conclude that self-reported sleep problems are highly prevalent, that they often persist throughout the year, that they often co-occur with DSM-IV mental disorders, and that they are associated with substantial self-reported role impairment that cannot be explained by comorbid mental disorders. As at least one of the self-reported measures of role impairment, days out of role, is known to be strongly related to objective measures (Kessler et al 2003; Kessler et al 2004b), we feel safe in concluding that self-reported sleep problems are significantly associated with true role impairments. Because of our failure to adjust for comorbid physical disorders, though, we cannot conclude that the associations of self-reported sleep problems with role impairment are due to causal effects of sleep problems. Sleep problems might, instead, be risk markers rather than causal risk factors for role impairment (Kraemer et al 1997).

The finding that approximately one-third of respondents reported one or more of the four sleep problems assessed in the NCS-R is broadly consistent with the results of other epidemiological surveys (Ancoli-Israel and Roth 1999; Grandner and Kripke 2004; National Sleep Foundation 2005). Our finding that NRS is the most common of the four sleep problems (25%, with the others in the range 16.4-19.9%) presumably reflects the fact that nonrestorative sleep it can occur as a result of DIS, DMS or EMA as well as in the absence of any of these three classic sleep problems. Furthermore, the fact that roughly one-third of people with NRS report neither DIS, DMS, nor EMA implies that nonrestorative sleep is sometimes indicative of poor sleep quality or continuity rather than short sleep duration. This is plausible in light of the fact that several sleep disorders (e.g., sleep apnea) have their primary effects on sleep quality and continuity rather than on sleep duration. At the same time, we found that sleep problems are highly inter-correlated, with roughly two-thirds of respondents who reported any having more than one. Furthermore, about one-third of respondents reported that their sleep problems persisted throughout the entire past 12 months. Chronicity is much more strongly associated with number than type of sleep problems.

The finding of modest socio-demographic correlates of sleep problems in the NCS-R is consistent with previous surveys (Roth and Roehrs 2003), although our more fine-grained analysis of separate sleep problem that in previous surveys showed an interesting specification involving age. DMS and EMA are higher among respondents in the 45-59 age range than those either younger or older, while DIS and NRS are most common among the young. These results clearly suggest that the focus of previous reports on increasing age as a risk factor for insomnia (Griffiths and Peerson 2005; Ohayon 2005) needs to be revised to recognize the heterogeneity of the different sleep problems associated with insomnia. For example, young people are much more likely than elderly people to stay up late, leading to daytime sleepiness that is not associated with difficulties in getting to sleep or staying asleep, even though young people have a low prevalence of difficulty initiating sleep.

The finding that sleep problems are highly comorbid with mental disorders is not surprising, but we failed to replicate the finding of several previous epidemiological studies that major depression is more strongly related to a diagnosis of insomnia than are other mental disorders (Breslau et al 1996; Ford and Kamerow 1989; Ohayon and Roth 2003). It is important to remember, though, that we examined sleep problems, not a DSM diagnosis of insomnia, while previous studies examined the latter. A DSM diagnosis of insomnia requires not only sleep problems but also daytime impairment associated with these problems. It might be, then, that sleep problems are associated with a wide range of mental disorders while the daytime impairment caused by sleep problems is associated more specifically with depression. Although exploration of this possibility goes beyond the bounds of the current report, it should be included in future investigations of sleep disturbance in depression.

The strength of the gross associations between sleep problems and role impairment is striking. This is especially true with regard to number of days out of role. Gross coefficients in predicting this outcome are in the range of 3.2 and 4.0 excess days per month associated with the individual sleep problems. These effects exceed those found in previous studies for most chronic physical and mental disorders in predicting days out of role (Kessler et al 2003). This is consistent with previous reports of strong gross associations between insomnia and days out of role (Simon and Von Korff 1997). Even though the size of these coefficients decreases substantially when controls are introduced for comorbid mental disorders, the fact that they remain statistically significant for all sleep problems other than EMA (with coefficients in the range 1.3-2.2 days) argues against the possibility that they are due to comorbid mental disorders. It is possible, though, that unmeasured comorbid physical disorders or systematic response bias explain part of the net associations.

It is important to recognize that the coefficients linking sleep problems to days out of role in the sub-sample of respondents without any DSM mental disorders are insignificant with the exception of the 2.0 excess days out of role per month associated with NRS. This finding is part of a larger pattern in the data that nonrestorative sleep is the sleep problem most consistently related to role impairment after controlling for comorbid mental disorders. This pattern is presumably due to the fact that nonrestorative sleep is the only type of sleep problem considered here that involves wake functioning rather than sleep functioning, implying that the effects of sleep problems on role impairment are strongly mediated by NRS.

It needs to be recalled, in light of the stronger associations of NRS than the other sleep problems with role impairment, that NRS was the only sleep problem assessed in the NCS-R with a dimensional scale. A dichotomization of this scale was created by selecting the cut-off point that maximized explained variance in role impairment. The other three sleep problems were assessed with simple dichotomies. Thus the relationship between NRS and role impairment could be spuriously elevated relative to the relationships involving the other sleep problems by the more precise assessment. As noted earlier in the paper in the section on measures, the NRS scale was dichotomized in order to parallel the dichotomous measures of the other three sleep problems. It might be that the finding that NRS is more strongly related to role impairment than the other sleep problems would be different if the other three problems had been measured dimensionally and dichotomized in a different way. It is relevant in this regard that DIS, DMS and EMA were all defined using conservative criteria. For example, in order to be classified as a DIS sufferer, a patient had to experience “two hours or longer in bed before falling asleep”, compared to the more widely used 30 minute sleep latency criterion used in other epidemiologic studies and clinical trials (Ohayon, 2005). Future research should consequently examine the sensitivity of results to variation in cut-points on these dimensions.

The results reported here leave a number of issues unresolved that could be addressed in the NCS-R data, but go beyond the boundaries of this first report. We already noted the need to explore the differential associations of depression and other DSM-IV mental disorders with sleep problems versus DSM-IV insomnia. In addition, future research should investigate the joint effects of multivariate sleep problem profiles, the effects of chronic versus intermittent sleep problems, the role of comorbid physical disorders, and the extent to which the associations of sleep problems with role impairment are due to daytime sleepiness. In addition, the recent report of the NIH consensus panel on insomnia noted that more research is needed on the associations of sleep problems with work performance and disability (National Institutes of Health 2005). All of these issues will be examined in ongoing analyses of the NCS-R data.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R) is supported by NIMH (U01-MH60220) with supplemental support from NIDA, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF; Grant 044708), and the John W. Alden Trust. Preparation of this report was additionally supported by a grant from Eli Lilly and Company. Collaborating investigators include Ronald C. Kessler (Principal Investigator, Harvard Medical School), Kathleen Merikangas (Co-Principal Investigator, NIMH), James Anthony (Michigan State University), William Eaton (The Johns Hopkins University), Meyer Glantz (NIDA), Doreen Koretz (Harvard University), Jane McLeod (Indiana University), Mark Olfson (Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons), Harold Pincus (University of Pittsburgh), Greg Simon (Group Health Cooperative), Michael Von Korff (Group Health Cooperative), Philip Wang (Harvard Medical School), Kenneth Wells (UCLA), Elaine Wethington (Cornell University), and Hans-Ulrich Wittchen (Max Planck Institute of Psychiatry). The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and should not be construed to represent the views of any of the sponsoring organizations, agencies, or U.S. Government. A complete list of NCS publications and the full text of all NCS-R instruments can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/ncs. Send correspondence to NCS@hcp.med.harvard.edu. The NCS-R is carried out in conjunction with the World Health Organization World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative. We thank the staff of the WMH Data Collection and Data Analysis Coordination Centres for assistance with instrumentation, fieldwork, and consultation on data analysis. These activities were supported by the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Pfizer Foundation, the US Public Health Service (R13-MH066849, R01-MH069864, and R01 DA016558), the Pan American Health Organization, Eli Lilly and Company, GlaxoSmithKline, and Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc. A complete list of WMH publications can be found at http://www.hcp.med.harvard.edu/wmhcidi.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. I. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S347–S353. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Roth T, Rosenthal L, Andreski P. Sleep disturbance and psychiatric disorders: a longitudinal epidemiological study of young adults. Biol Psychiatry. 1996;39:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(95)00188-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chwastiak LA, Von Korff M. Disability in depression and back pain: evaluation of the World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule (WHO DAS II) in a primary care setting. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:507–514. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirignotta F, Mondini S, Zucconi M, Lenzi PL, Lugaresi E. Insomnia: an epidemiological survey. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1985;8(Suppl 1):S49–S54. doi: 10.1097/00002826-198508001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa e Silva JA, Chase M, Sartorius N, Roth T. Special report from a symposium held by the World Health Organization and the World Federation of Sleep Research Societies: an overview of insomnias and related disorders--recognition, epidemiology, and rational management. Sleep. 1996;19:412–416. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.5.412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, Williams JBW. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV-TR Axis I Disorders, Research Version, Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP) Biometrics Research, New York State Psychiatric Institute; New York, NY: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. An opportunity for prevention? JAMA. 1989;262:1479–1484. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.11.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grandner MA, Kripke DF. Self-reported sleep complaints with long and short sleep: a nationally representative sample. Psychosom Med. 2004;66:239–241. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000107881.53228.4d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths MF, Peerson A. Risk factors for chronic insomnia following hospitalization. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:245–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03283.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz DA, McHorney CA. The relationship between insomnia and health-related quality of life in patients with chronic illness. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:229–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Abelson J, Demler O, Escobar JI, Gibbon M, Guyer ME, et al. Clinical calibration of DSM-IV diagnoses in the World Mental Health (WMH) version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (WMHCIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004a;13:122–139. doi: 10.1002/mpr.169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ames M, Hymel PA, Loeppke R, McKenas DK, Richling D, et al. Using the WHO Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) to evaluate the indirect workplace costs of illness. J Occup Environ Med. 2004b;46:s23–7. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000126683.75201.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Barber C, Beck A, Berglund P, Cleary PD, McKenas D, et al. The World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (HPQ) J Occup Environ Med. 2003;45:156–174. doi: 10.1097/01.jom.0000052967.43131.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Chiu WT, Demler O, Heeringa S, Hiripi E, et al. The US National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): design and field procedures. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004c;13:69–92. doi: 10.1002/mpr.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, Zhao S, Nelson CB, Hughes M, Eshleman S, et al. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Merikangas KR. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R): background and aims. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:60–68. doi: 10.1002/mpr.166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Ustun TB. The World Mental Health (WMH) Survey Initiative Version of the World Health Organization (WHO) Composite International Diagnostic Interview (CIDI) Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2004;13:93–121. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer HC, Kazdin AE, Offord DR, Kessler RC, Jensen PS, Kupfer DJ. Coming to terms with the terms of risk. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54:337–43. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160065009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leger D, Scheuermaier K, Philip P, Paillard M, Guilleminault C. SF-36: evaluation of quality of life in severe and mild insomniacs compared with good sleepers. Psychosom Med. 2001;63:49–55. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200101000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health State of the Science Conference Statement: Manifestations and management of chronic insomnia in adults. Sleep. 2005;28:1049–1057. doi: 10.1093/sleep/28.9.1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Sleep Foundation . Summary of Findings: 2005 Sleep in America Poll. Vol. 2005. National Sleep Foundation; Washington, DC: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon M. Epidemiological study on insomnia in the general population. Sleep. 1996;19:S7–S15. doi: 10.1093/sleep/19.suppl_3.s7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV diagnostic criteria of insomnia: distinguishing insomnia related to mental disorders from sleep disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 1997;31:333–346. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(97)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM. Epidemiology of insomnia: what we know and what we still need to learn. Sleep Med Rev. 2002;6:97–111. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2002.0186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM. Prevalence and correlates of nonrestorative sleep complaints. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:35–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohayon MM, Roth T. Place of chronic insomnia in the course of depressive and anxiety disorders. J Psychiatr Res. 2003;37:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(02)00052-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Research Triangle Institute . SUDAAN: Professional Software for Survey Data Analysis. 8.01 ed. Research Triangle Institute; Research Triangle Park, NC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Roth T, Roehrs T. Insomnia: epidemiology, characteristics, and consequences. Clin Cornerstone. 2003;5:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s1098-3597(03)90031-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon GE, Von Korff M. Prevalence, burden, and treatment of insomnia in primary care. Am J Psychiatry. 1997;154:1417–1423. doi: 10.1176/ajp.154.10.1417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolter K. Introduction to Variance Estimation. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1985. [Google Scholar]