Abstract

Introduction

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) is a ubiquitous herpes virus that persists in the host in a latent state following primary infection. We have recently observed that CMV reactivates in lungs of critically ill surgical patients, and that this reactivation can be triggered by bacterial sepsis. Although CMV is a known pathogen in immunosuppressed transplant patients, it is unknown whether reactivated CMV is a pathogen in immunocompetent hosts. Using an animal model of latency/reactivation, we studied the pathobiology of CMV reactivation in the immunocompetent host.

Methods

Cohorts of immunocompetent BALB/c mice with or without latent murine CMV (MCMV+/MCMV−) underwent cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Lung tissue homogenates were evaluated after CLP for TNF-α, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-2 mRNA by PCR and real time quantitative RT-PCR. Because pulmonary TNF-α expression is known to cause pulmonary fibrosis, trichrome stained sections of lung tissues were analyzed using image analysis to quantitate pulmonary fibrosis. In a second experiment, a cohort of MCMV+ mice received ganciclovir (10mg/kg/day sq) following CLP. TNF-α mRNA and pulmonary fibrosis were evaluated as above.

Results

All MCMV+ mice had CMV reactivation beginning 2 weeks after CLP. Following reactivation, these mice had abnormal TNF-α, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-2 mRNA expression compared to controls. Image analysis showed that MCMV+ mice had significantly increased pulmonary fibrosis compared to MCMV− mice 3 weeks after CLP.

Ganciclovir treatment following CLP prevented MCMV reactivation. Further, ganciclovir treated mice did not demonstrate abnormal pulmonary expression of TNF-α mRNA. Finally, ganciclovir treatment prevented pulmonary fibrosis following MCMV reactivation.

Conclusions

This study shows that CMV reactivation causes abnormal TNF-α expression, and that following CMV reactivation immunocompetent mice have abnormal pulmonary fibrosis. Ganciclovir blocks MCMV reactivation, thus preventing abnormal TNF-α expression and pulmonary fibrosis. These data may explain a mechanism by which critically ill surgical patients develop fibroproliferative ARDS. These data suggest that human studies using antiviral agents during critical illness are warranted.

INTRODUCTION

Human cytomegalovirus (HCMV) has been recognized as a pathogen for many years in immunosuppressed patients, and until the advent of effective anti-viral therapy was a life-threatening complication of transplantation[1]. Like other beta herpes viruses, HCMV becomes latent following primary infection, lying dormant until some stimulus causes reactivation. Latency is the viral state in which complete viral genomes reside in host cells, without production of intact infectious virions. Following an adequate stimulus, latent viral genes can reactivate and produce infectious virus. Although HCMV is well recognized as a pathogen in immunosuppressed patients, it has garnered little attention in immunocompetent patients because of its believed benign course.

Recent work has shown that high percentages of non-immunosuppressed critically ill surgical patients previously infected with HCMV are susceptible to HCMV reactivation during their critical illness, and that HCMV may not be as benign as once believed[2–5]. Our work and that of others has shown that reactivation of HCMV can occur in the lungs [2, 3, 6–8], which are known to be a reservoir for latent HCMV[9]. Pulmonary HCMV has been associated with increased duration of mechanical ventilation[3, 6, 10], as well as increased length of hospitalization[3, 6, 10], and possibly worsened mortality[2, 4]. Because of inherent limitations in human subjects, very little is known about the pathobiology of HCMV in critically ill surgical patients.

Because there are no adequate in-vitro models, we utilize a well described in-vivo model of murine CMV (MCMV) to study reactivation[11–13]. MCMV has been well characterized, and is very similar to HCMV[14, 15]. Using a susceptible BALB/c mouse strain, intra-peritoneal inoculation of MCMV causes acute infection, with subsequent development of latency in host tissues[13, 15]. Like its HCMV counterpart, MCMV has been shown to develop latency in many organs, including lung tissue[15–18]. We have recently published a model of reactivation from latency using bacterial sepsis as a trigger[13]. This model affords a unique opportunity to study reactivation of CMV, and its pathologic consequences, in lungs of previously immunocompetent hosts.

This study was undertaken to evaluate the effects of CMV reactivation upon cytokine/chemokine expression in the lungs of previously immunocompetent hosts. Further, the effects of antiviral therapy on both viral reactivation and cytokine/chemokine expression were studied. Finally, the effect of CMV reactivation upon pulmonary fibrosis was evaluated using novel computer image analysis techniques. We present data herein, which suggest that local tissue cytokine expression in hosts latently infected with CMV is abnormally up-regulated following CMV reactivation, and that this causes pathology in the previously immunocompetent host.

Methods

Animals, viral infection, and confirmation of latency

Female BALB/c mice (Harlan, Indianapolis IN) 6–8 weeks of age were used in this study. Purified Smith strain (VR-194/1981) murine CMV was obtained from ATCC (Rockville, MD). Primary CMV infection was achieved by intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection of 2 × 104 PFU Smith strain MCMV. Following MCMV infection, a cohort of five mice was euthanised at 16 weeks to confirm latent MCMV infection. Mice were euthanised by cervical dislocation under inhalation anesthesia. Mouse lungs and salivary gland were dissected aseptically and were frozen immediately in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80°C. Tissue samples were evaluated by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and reverse transcription PCR (RT-PCR) to confirm primary infection and latency/reactivation respectively. As previously published, we define latency as having viral DNA present in host tissues, without transcription of viral genes[13, 17–20]. This differs somewhat from the definition used in human studies, which often rely on demonstration of live virus by culture, or worse yet by immunoglobulin status, since tissue biopsies often are not possible.

All mice were housed in a large animal facility, isolated from other mice, adhering to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals prepared by the National Research Council (NIH Publication No. 86-23, revised 1985) following protocol approval by our Institutional Review Board.

CMV Reactivation

We have previously published that an LD50 model of cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) will stimulate pulmonary reactivation of latent MCMV in 100% of surviving mice[13]. Reactivation is not isolated to lungs, also occurring in liver, spleen, and salivary glands (unpublished data). As previously described, reactivation from latency is defined as having mRNA transcription of later viral genes[13, 17–20] (for a review see [21]). Viral mRNA becomes detectable between 7 and 14 days following CLP with this model, with peak viral mRNA transcription occurring 21 days after CLP[13].

For these experiments, mice underwent (CLP) via laparotomy under general anesthesia slightly modified from that previously described by Baker et al[22]. Briefly, through a lower midline incision, the cecum was delivered, ligated with a silk suture 1 cm from the tip, and singly punctured with a 23 gauge needle. The laparotomy was closed with running monofilament suture.

Three groups underwent CLP for these experiments: The first cohort (CMV+, n=45) was latently infected with MCMV. Following CLP, groups of surviving CMV+ mice (3–5) were euthanised at 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after CLP (n=3, 3, 4, 5, 4, 5 respectively). As controls, a second cohort of healthy mice underwent CLP (CMV−, n=24), and pairs of surviving CMV− mice were euthanised at 1, 2, 3, 7, 14, and 21 days after CLP. Finally, a third cohort was latently infected with MCMV, underwent CLP, and received daily treatment with ganciclovir (10mg/kg/day sub Q) beginning the day after CLP (CMV+GCV, n=30). Cohorts of surviving CMV+GCV mice were euthanised at 7, 14, and 21 days after CLP (n = 4, 5, 5 respectively).

Ganciclovir dosing of 10mg/kg/day (in 0.2 cc saline vehicle) was chosen because this has been shown to be efficacious in mice[23, 24]. This is also a standard dose in adults for CMV disease. Saline injected controls for the GCV experiment were not done because previous work by us has shown that neither sham surgery [13] nor saline injection (unpublished data) are sufficient to influence reactivation. For all groups, following euthanasia, lung tissues were evaluated for viral reactivation and inflammatory mediator expression using PCR and RT-PCR. Tissue samples were also fixed in formalin and paraffin embedded for histologic analyses.

PCR, RT-PCR, and nested PCR

All PCR and RT-PCR reactions for transcription of MCMV immediate early 1 (IE-1), MCMV glycoprotein B (GB) and beta actin (β-actin) genes were performed using previously published primers[13]. Tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) and interleukin 1-beta (IL-1β) primer sets were obtained from Stratagene. Primers for neutrophil chemokine KC (KC) and macrophage inflammatory protein 2 (MIP-2) were synthesized using sequences described previously by Salkowski et al[25].

DNA were extracted from tissues using QIAamp Tissue Kit (QIAGEN GmbH, Hilden, Germany). DNA extracted from tissue homogenates were eluted in 100 μl of distilled water and stored at −20°C until analysis. DNA were amplified in a total volume of 25μl with 200 nM of each primer and 1.0 U of Taq DNA polymerase (GIBCO BRL) added in 2.5 μl of a PCR buffer (50 mM KCl, 20mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), and 1.5 mM MgCl2). PCR reactions were carried out using a Perkins Elmer 9700 thermocycler (PE Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA), using the following program: initial denaturation 4 min at 94°C, 35 cycles-denaturation 30s at 94°C, annealing 30s at 53°C, elongation 30s at 72°C, followed by final elongation 7 min at 72°C, then hold at 4°C. Beta-actin transcripts were used as a cellular transcript control. Amplification products were separated by electrophoresis in 1% agarose gels, and gels were stained with ethidium bromide.

RNA were extracted from tissues using TRIzol Reagent (GIBCO BRL, Carlsbad CA), dissolved in 100 ll DEPT water, and stored at −80°C. Reverse transcription (RT) reactions were carried out using 1-5μg RNA digested with 1 U DNase I (GIBCO BRL) at 37°C for 20 min. The RT reaction was performed in a total volume of 20 μl, containing 60 mM KCl, 15 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.4), 3 mM MgCl2, 10 mM dithiothreitol, 20% (vol/vol) glycerol, 1 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate, 12.5 pM of random primer (GIBCO BRL), and 2.5 U Super-transcriptase (GIBCO BRL). Primer annealing was done for 10 min at 25°C and reverse transcription was carried out for 30 min at 42°C, then digestion with 1 U RNAseH, followed by denaturation for 5 min at 95°C. To control for DNA contamination, every sample had a concomitant parallel experiment with no RT reaction.

Following RT reactions, 2μl of the resulting cDNA were amplified using the same conditions as outlined above for PCR reactions. If this first reaction yielded no visible product, a second (nested) PCR was performed using 1μl of this first PCR reaction product. Estimated sensitivity for CMV detection is 10-100 copies (unpublished data).

Quantitative real time PCR and RT PCR

Primer sets and fluorescence resonance energy transfer type probes were designed and optimized for MCMV GB, TNF-α, and β-actin genes. Plasmids homologous to the sequences amplified by our PCR primers were cloned for these genes, and using serial dilution of known plasmid concentrations, standard curves were constructed for quantitation. Regression equations had very high R2 values (95% β-actin, 96% TNF, and 99% GB), and were used for subsequent copy number calculations. Real time PCR results are expressed as copies of DNA/mRNA per copies of β-actin. All samples were analyzed in duplicate, and results are expressed as mean copies ± Standard error of mean.

Sequences for real time primers/probes designed are as follows: TNF-α {forward agttcccaaatggcctccc, reverse acgacgtgggctacaggc, probe tatggcccagaccctcacactc}, β-actin {forward attgtgatggactccggtga, reverse agctcatagctcttctccag, probe cacccacactgtgcccatctac}, CMV GB {forward tgtactcgaagggagagct, reverse cgttcaccaccgaagacac, probe cgcctcgaacgtgttcagcctg}.

Image Analysis for fibrosis

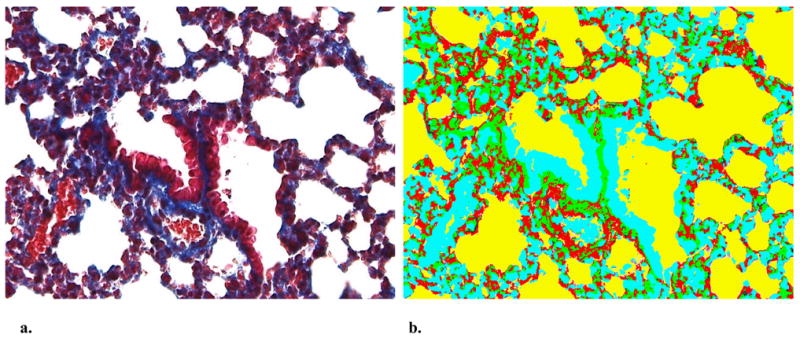

Lung tissues from latently infected (CMV+), non-infected (CMV−), and latently infected ganciclovir treated (CMV+ GCV) mice were obtained 3 weeks after CLP. Lung tissues were fixed, sectioned, and stained with trichrome to identify the presence of mature collagen and fibrosis. Using computer image analysis techniques (detailed below), 10 random areas of interest were imaged and image segmentation was performed. Examples are shown in figures 1a & 1b. The surface areas of the segmented images were calculated with image analysis software for the four segmented colors (fibrosis, Blank space, cytoplasm, or nuclei). Following quantitation of fibrosis, comparisons were performed between mice with reactivated CMV (CMV+), without (CMV−), and latently infected mice with reactivation blocked (CMV+ GCV). Our image analysis technician is blinded to all study groups to prevent bias.

Figure 1.

a. Representative Gomori’s trichrome stained lung section from mouse following cecal ligation and puncture (40X). b. Corresponding computer segmented image of lung section utilized for estimation of fibrosis (40X). After segmentation into four colors (representing fibrosis, blank space, cytoplasm, or nuclei), image analysis software was utilized to determine % of fibrosis (blue in trichrome, green in segmented image)

Specifically, slides are imaged using a Hitachi HV-C20-SA 3CCD color camera mounted on an Olympus® BX-51 research microscope. The microscope has a Prior® H101 precision motorized stage driven by a ProScan™ advanced stage controller. The camera and stage are controlled via the Image-Pro Plus software. Imaging tissue sections are automated using an Image-Pro Plus macro calibrated for each microscope objective. Initial objective measurement calibration is accomplished using a precision 0.01mm stage micrometer, saving the calibration settings within the macro to facilitate batch processing. Once the slide is placed on the stage, the proper objective is selected, stage travel limits are set and focus adjusted. The macro captures 640×480 pixel blocks within the stage travel limits to build a completed full color image. Images are acquired using Media Cybernetics® Image-Pro® Plus version 4.5 on a Dell OptiPlex GX400 computer with Windows® 2000 Pro operating system. ®. Following image segmentation, fibrosis (represented as blue on trichrome, segmented to green, see figure below) was quantitated. Percent area and integrated optical density (IOD) were averaged for each slide across all areas of interest (AOIs), and standard deviations were calculated. Area in mm2, percent area and IOD were used to compare the amount of fibrosis for each experimental group. Images are stored as uncompressed jpeg or TIF files. Tissue features from selected AOIs are analyzed for number of objects, percent of objects, percent area, and IOD. Five to ten AOIs are selected from each large image randomly using a macro to capture a series of 640×480 pixel blocks. Areas of interest are selected from a specific tissue section, on each slide, with the position of the tissue section recorded as counted from the slide label. Similar sections are then analyzed on each subsequent slide. AOIs are captured at 48-bit pixel depth and the images saved for analysis. Each selected tissue feature is assigned a unique color (segmentation) using the Hue, Saturation, and Intensity (HSI) color model. Segmentation allows individual features to be separated from background noise prior to analysis. Data were exported to Microsoft® Excel for analysis.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses including Kruskal-Wallace test (non-parametric analysis of variance), two tailed Students t-test, Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test, and Fisher’s exact test, were performed where appropriate. For quantitative TNF-α data, a log transformation was used to symmetrize the distributions and, more importantly, stabilize the variances for each group-time batch, so that these variances no longer increased with mean values. Robust estimates of the standard deviations for technical and biological variability were .72 and .51, respectively, indicating the importance of replication. A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant for all testing. Means are expressed as mean ± standard error. Statistical software used was Excel (Microsoft) and S-Plus 7.0 (Insightful Corporation).

Results

CLP causes pulmonary MCMV reactivation

Cecal ligation and puncture caused detectable pulmonary reactivation of latent MCMV between day 7 and 14 in CMV+ mice, which is consistent with our previously published results[13] (Figure 2). There was no MCMV mRNA expression in non-infected healthy mice undergoing CLP (CMV−, data not shown). Overall survival following CLP was not significantly different between groups (53% CMV+, 50% CMV−, and 47% in GCV-CMV+ mice), which is also consistent with our previously published results[13].

Figure 2.

Pulmonary reactivation of latent murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) occurred between 7 and 14 days after bacterial sepsis. Mice latently infected with MCMV underwent CLP, and lung homogenates were evaluated for viral activity by RT-PCR for MCMV mRNA. Controls refer to technique controls.

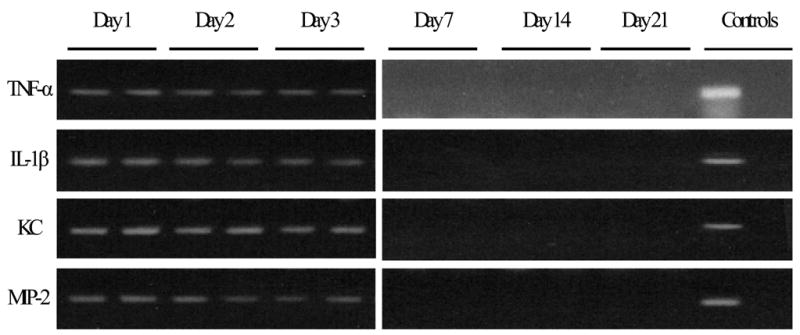

MCMV reactivation causes prolonged pulmonary inflammation

Lung tissue expression of cytokines and chemokines has been well-characterized following CLP and endotoxemia. Numerous inflammatory cytokines/chemokines are induced by either stimulus, including TNF-α, IL-1β, chemokine KC and MIP-2[26–28]. Our results from non-infected healthy CMV− control mice undergoing CLP corroborate those previously published by other investigators. There was transcription of pulmonary TNF-α, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-2 mRNA occurring 24–72 hours after CLP, which became undetectable by day seven after CLP (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Healthy mice have transcription of cytokines/chemokines after CLP. Pairs of mice underwent evaluation of pulmonary cytokine/chemokine transcription after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Confirming previous studies, there was detectable TNF-α, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-2 mRNA expression for 1–3 days after CLP, which became undetectable by day 7. Each lane represents 1 mouse. No RT reaction controls were performed in parallel and were all negative (data not shown).

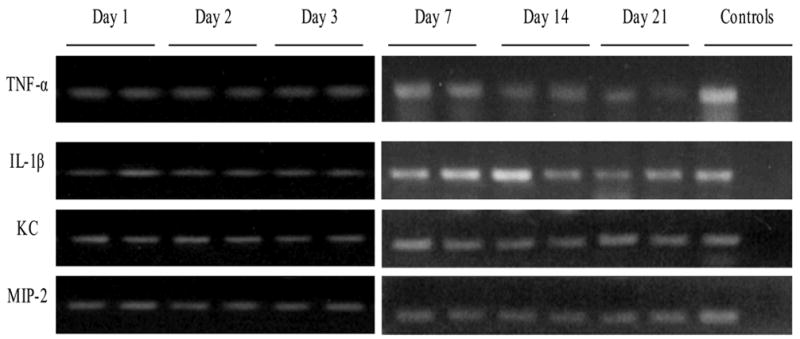

Similar to normal controls, CLP caused early pulmonary transcription of cytokine/chemokine mRNA in mice latently infected with MCMV (Figure 4). However, in contrast to controls, latently infected mice had prolonged pulmonary expression of these inflammatory mediator mRNAs, which persisted for three weeks after CLP and MCMV reactivation. Prolonged pulmonary inflammation following bacterial sepsis and MCMV reactivation suggest a possible mechanism of pathology for reactivated MCMV.

Figure 4.

Mice latently infected with murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) have abnormal transcription of cytokines/chemokines after cecal ligation and puncture (CLP). Groups of mice underwent evaluation of pulmonary cytokine/chemokine transcription after CLP. Unlike uninfected hosts, there was detectable TNF-α, IL-1β, KC, and MIP-2 mRNA expression that persisted for 3 weeks after CLP, suggesting that CMV reactivation might cause prolonged inflammation and possibly pulmonary pathology following bacterial sepsis. Each lane represents 1 mouse. No RT reaction controls were performed in parallel and were all negative (data not shown).

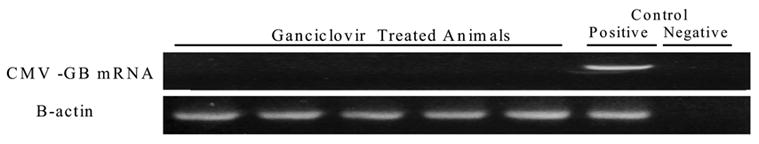

Ganciclovir prevents pulmonary MCMV reactivation

To test the hypothesis that MCMV reactivation triggered by bacterial sepsis can be blocked by ganciclovir, latently infected mice were treated prophylactically with ganciclovir (10mg/kg/day SQ) after CLP (CMV+GCV). Our previous experience has shown that MCMV replication occurs maximally three weeks after CLP reactivation[13], therefore the cohort was analyzed for signs of reactivation at this time point. Nested RT-PCR shows no viral transcription (Figure 5), indicating that administration of ganciclovir after CLP blocks reactivation of latent MCMV induced by bacterial sepsis.

Figure 5.

Pulmonary murine cytomegalovirus (MCMV) reactivation following CLP is prevented by antiviral therapy. Latently infected mice underwent CLP with postoperative ganciclovir treatment (10mg/kg/day sq) and were analyzed three weeks after CLP. Nested RT-PCR shows no viral transcription. Each lane represents 1 mouse. Controls refer to technique controls.

Blocking MCMV reactivation prevents prolonged pulmonary inflammation

To further evaluate the abnormal pulmonary cytokine/chemokine expression seen in mice following CLP and MCMV reactivation, quantitative real time RT-PCR was utilized. Specifically, pulmonary TNF-α mRNA transcription was quantitated at the various time points after CLP for mice latently infected with CMV (CMV+), non-CMV infected controls (CMV−), and ganciclovir treated CMV+ mice (CMV+GCV).

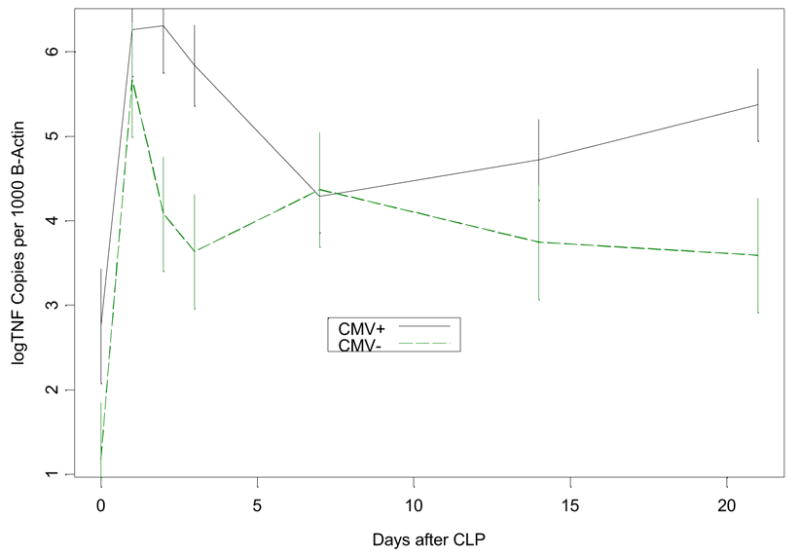

In CMV− control mice there was a normal TNF-α transcriptional response to CLP, with TNF-α mRNA levels peaking at day one, decreasing by day 2, returning to baseline for the remaining 3 weeks (Figure 6a). In contrast, CMV+ mice undergoing CLP had an initial TNF-α mRNA response that was prolonged for 3 days, compared to only 1 day in CMV− mice. TNF-α expression in latently infected mice (CMV+) then returned to baseline by day 7 after CLP, however, at day 14 levels began to rise until becoming significantly elevated again by day 21 after CLP (Figure 6a). Interestingly, reactivation of latent MCMV occurred in all CMV+ mice prior to this late rise in TNF-α expression, between day 7 and 14 after CLP.

Figure 6.

Figure 6a Comparison of pulmonary TNF-α mRNA expression following cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) in mice latently infected with murine cytomegalovirus (CMV+) versus healthy controls (CMV−). Mice underwent CLP and lung tissue homogenates were evaluated at 0,1,2,3,7,14, and 21 days for TNF-α mRNA using real time PCR. Error bars were formed to indicate a multiple comparison adjusted p-value of .05 between groups at any time point where there is no overlap. CMV− mice showed normal TNF-α mRNA expression, which peaks at day one and returns back toward baseline levels by day 2–3 after CLP. In contrast, CMV+ mice had persistence of this day one peak in TNF-α mRNA expression for 3 days before returning toward baseline, showing a second elevation at day 21 after MCMV reactivation.

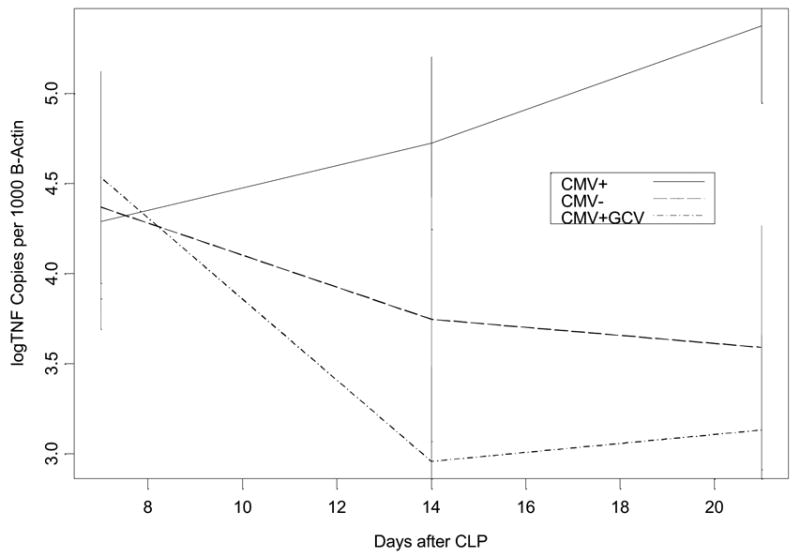

Figure 6b Comparison of late pulmonary TNF-α mRNA expression following CLP in mice latently infected with MCMV treated with ganciclovir (CMV+GCV), latent MCMV (CMV+), and healthy controls (CMV−). Mice underwent CLP and lung tissue homogenates were evaluated at 7, 14, and 21 days for TNF-α mRNA using real time PCR. Error bars were formed to indicate a multiple comparison adjusted p-value of .05 between groups at any time point where there is no overlap. Treatment with GCV prevented CMV reactivation in CMV+GCV mice (see results), and CMV+GCV mice showed TNF-α mRNA expression that was not significantly different from CMV− mice.

These findings suggested a possible pathogenic role of CMV during critical illness. If CMV reactivation in the lungs is pro-inflammatory, then CMV reactivation could in fact worsen or prolong ongoing lung injury. To test the hypothesis that MCMV reactivation causes the elevation of pulmonary TNF-α mRNA transcription at day 21, CMV+GCV treated mice were analyzed. Figure 6b shows that when CMV reactivation was blocked, TNF-α mRNA expression was not significantly different than non-infected controls. We therefore conclude that CMV reactivation is related to increased inflammation in pulmonary tissues.

CMV reactivation causes pulmonary injury

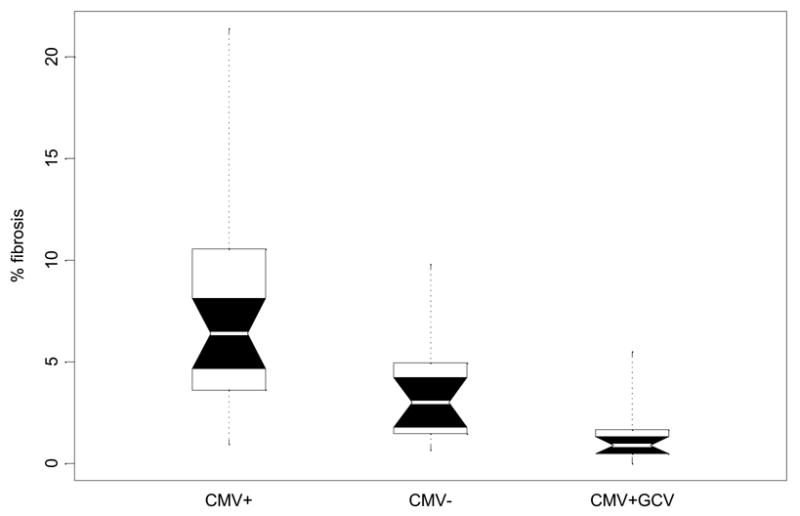

TNF-α, through secondary release of TGF-β, PDGF-a, and PDGF-β, has been causally linked to pathologic changes known as interstitial pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)[29, 30]. We therefore hypothesized, that the elevated TNF-α mRNA transcription seen following viral reactivation may be injurious, causing increased fibrosis after MCMV reactivation. Figure 7 shows that there was a significant increase in pulmonary fibrosis in latently infected CMV+ mice when compared with CMV− controls after stimulation with bacterial sepsis. Treatment with ganciclovir (CMV+GCV) after CLP in latently infected mice completely abrogated this increase in fibrosis.

Figure 7.

Boxplot comparison of pulmonary fibrosis in latently infected (CMV+), non-infected (CMV−) and ganciclovir treated (CMV+GCV) mice 3 weeks after cecal ligation and puncture. White belts indicate the median value. Boxes give the range between quartiles (25th and 75th percentiles). Notched black regions are 95% confidence intervals for the medians, and the dots indicate the full range of the distributions. Because distributions of pulmonary fibrosis scores are non-normal, nonparametric tests were used to discern differences among study groups at day 21. Post hoc comparisons of pairs of groups were made using the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon test (nonparametric t-test). CMV reactivation was related to significant increases in pulmonary fibrosis compared to healthy controls after CLP (p<0.0007). Blocking CMV reactivation with ganciclovir after CLP appears to prevent this increased level of fibrosis, as fibrosis was significantly lower in GCV treated mice than in non treated mice (p<.0002),

There was slightly less fibrosis in CMV+GCV mice when compared to CMV−CLP controls (Figure 7), suggesting that GCV may have anti-inflammatory effects, and that the lack of fibrosis in CMV+GCV mice might not be due to prevention of CMV reactivation. To test this hypothesis, a cohort of normal mice (n=14) underwent CLP. Half received ganciclovir 10mg/Kg/day sq subsequent to CLP, and half received saline as controls. There was no significant difference in survival between the groups (data not shown). Further, image analysis showed no significant difference in pulmonary fibrosis between these groups, confirming that GCV does not have anti-inflammatory properties after CLP (data not shown). Taken together, we conclude that sepsis triggered CMV− reactivation causes pulmonary fibrosis.

DISCUSSION

This study shows that CMV reactivation causes abnormal pulmonary cytokine/chemokine expression, and suggests further, that CMV reactivation may cause pathology in the immunocompetent host. Although we have recognized for many years that CMV can reactivate during critical illness, it is has been unclear whether these viral reactivations represent pathologic processes, or are simply surrogates of severe illness. HCMV is recognized as a pathogen in immunosuppressed patients, and despite modern antiviral therapies, HCMV still causes significant morbidity in this population. It is intriguing that a ubiquitous herpes family virus such as CMV may reactivate during critical illness, modulating or contributing to organ failure, which eventually kills so many critically ill surgical patients.

These studies were performed to determine the effects of viral reactivation in previously “immunocompetent hosts”. We have chosen the nomenclature “immunocompetent host”, understanding that during critical illness, and particularly during intra-abdominal sepsis, host immune function may be transiently altered [31–34]. This nomenclature was specifically chosen to distinguish these hosts from those with underlying chronic immunosuppressive conditions, such as AIDS or transplant patients. While the pathologic effects of CMV reactivation in chronically immunosuppressed patients are well known, little is known about the pathobiology of CMV reactivation in hosts that were immunocompetent prior to their critical illness.

Our results support the hypothesis that MCMV reactivation following bacterial sepsis causes abnormal pulmonary expression of inflammatory cytokines/chemokines. Bacterial sepsis is known to induce pulmonary expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, chemokine KC and MIP-2 in healthy mice, but this expression is self limited, returning to baseline after 2–3 days[26–28]. These previously published results are confirmed in this study (Figure 3). In contrast, qualitative PCR analysis of CMV+ mice undergoing CLP show a prolonged pulmonary expression of TNF-α, IL-1β, chemokine KC and MIP-2 mRNA, which persists at least three weeks after CLP induced bacterial sepsis (Figure 4). These results suggested that MCMV reactivation could contribute to or modulate pulmonary inflammation after sepsis.

To further analyze this difference, we utilized real time RT-PCR to quantitate pulmonary TNF-α mRNA expression. There appear to be at least two significant differences in pulmonary TNF-α mRNA expression in CMV+ hosts undergoing reactivation. First, there is a very prominent exaggeration in the initial TNF-α mRNA response (Figure 6a) following CLP in CMV+ mice. This initial surge of TNF-α mRNA persists for 3 days after CLP in lungs of CMV+ mice, whereas in CMV− mice, it rather abruptly returns to normal. One possible explanation for this is that there are higher numbers of immune cells in the organs of latently infected hosts. Podlech et al. have previously shown that there is a lifelong persistence of CD8 T-cells in pulmonary tissues after clearance of acute MCMV infections[35], and we suspect that these T-cells may be responsible for the initial exaggeration in TNF-α mRNA expression. In addition, CMV is known to stochastically attempt reactivation; however, the presence of a healthy immune system usually prevents this from going to completion[36]. Nonetheless, these stochastic attempts at reactivation may lead to further immune cells being recruited into the area, which might exaggerate an initial inflammatory response. Studies to further elucidate the source of this initial surge in TNF-α mRNA expression are currently ongoing.

The second major difference in pulmonary TNF-α mRNA expression in CMV+ hosts undergoing CLP occurs after CMV becomes reactivated, when pulmonary TNF-α mRNA levels again become elevated above normal. This second elevation of tissue TNF-α mRNA expression may represent a natural host immune response to CMV reactivation in the lungs. This immune response may be mobilized to control the virus, but in so doing may cause end organ injury by proximity. Another explanation is that CMV might be directly modulating tissue cytokine expression. Certain CMV transcripts are known to effect and/or modulate expression of inflammatory mediators, including TNF-α, IL-1β, NF-κB, and chemokine IL-8, among others[37–44]. Interestingly, these are many of the same mediators that have been shown to be stimulatory to CMV replication[45, 46]. It is therefore possible, that tissue expression of cytokines/chemokines is modulated by CMV, representing an autocrine mechanism by which CMV stimulates itself to insure survival. Whichever the cause, the fact that blocking CMV reactivation with antiviral therapy prevents this abnormal tissue expression strongly supports the hypothesis that CMV is responsible for this late elevation in TNF-α mRNA expression.

Whatever the cause of the observed abnormal TNF-α transcription, abnormal pulmonary expression of TNF-α appears to be injurious. Mice latently infected with MCMV had significantly higher levels of pulmonary fibrosis than non-CMV− infected mice after bacterial sepsis (Figure 7). Perhaps more convincing are the CMV+GCV mice that received ganciclovir after CLP. These mice did not have CMV reactivation, had normal TNF-α transcription, and subsequently did not have the degree of pulmonary fibrosis demonstrated by CMV+ mice undergoing CLP. Taken together, these data suggest that pulmonary fibrosis may be a direct consequence of CMV reactivation, which may be partly mediated by TNF-α.

This hypothesis is supported by current literature. Numerous models have shown that TNF-α is a critical mediator of pulmonary fibrosis[47–50]. In addition to its direct effects, TNF-α also stimulates release of secondary fibrogenic cytokines, namely transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β) and platelet derived growth factors alpha and beta (PDGF-α and PDGF-β)[29, 30]. TGF-β has been shown to induce fibroproliferative lung disease[51, 52]. Although we have not yet studied these secondary mediators, we hypothesize that TNF-α mRNA expression seen during MCMV reactivation might cause pathology by this mechanism, resulting in pulmonary fibrosis.

Regardless of the specific mechanism, these results very clearly address the issue of pathogen versus innocent bystander for CMV reactivation. Previously, there have been several studies linking herpes family virus reactivations in critically ill patients with significantly increased durations of mechanical ventilation or intensive care unit lengths of stay when compared to patients without reactivation[2–5, 53]. Some of these studies have also suggested a link between viral reactivation and ARDS[3, 53], as well as worsened mortality following CMV reactivation[2, 4]. We now suspect that reactivated CMV may actually be a pathogen, and not simply a surrogate or indicator of severity of critical illness.

These animal data clearly describe a mechanism by which CMV might act as a pulmonary pathogen in critically ill patients. While this may seem intuitively to be an inconsequential problem, our previous epidemiologic work has shown that latent HCMV is highly prevalent in critically ill patients, putting > 70% of them “at risk” for reactivation[3]. Indeed, using very conservative techniques, at least 5–25% of those “at risk” reactivate HCMV during their critical illness[3]. Given the magnitude of latent HCMV in our critically ill population, therefore, the time has come to move forward in developing strategies for both recognizing and treating this potential pathogen. Fortunately, our data suggest that CMV reactivation may be preventable with antiviral therapy. Studies to address timing of administration, as well as alternate dosing regimens of antivirals are ongoing, which should facilitate taking these novel findings back to the bedside.

In conclusion, CMV reactivation in the immunocompetent host causes abnormal pulmonary tissue expression of numerous cytokines/chemokines. These cytokines/chemokines likely cause the resultant pulmonary fibrosis seen following CMV reactivation. Fortunately, treatment with ganciclovir prevents CMV reactivation following bacterial sepsis, preventing abnormal cytokine/chemokine transcription, thus preventing pulmonary fibrosis. Taken together, these data describe a mechanism by which CMV reactivation may cause lung injury in critically ill patients. Further study utilizing antiviral therapy in critically ill humans is thus warranted.

Footnotes

No authors have any financial interests to disclose.

Presented in part: 23rd annual meeting of the Surgical Infection Society, San Antonio, Texas 10-12 April, 2003 (abstract 1). Winner of Annual SIS Joseph Susman Memorial Award 2003.

This work was supported by NIH grant R01GM066115, Bethesda, MD.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- 1.Simmons RL, et al. Clinical characteristics of the lethal cytomegalovirus infection following renal transplantation. Surgery. 1977;82(5):537–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cook CH, et al. Occult herpes family viruses may increase mortality in critically ill surgical patients. American Journal of Surgery. 1998;176(4):357–60. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(98)00205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cook CH, et al. Occult herpes family viral infections are endemic in critically ill surgical patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2003;31(7):1923–9. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000070222.11325.C4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heininger A, et al. Human cytomegalovirus infections in nonimmunosuppressed critically ill patients. Critical Care Medicine. 2001;29(3):541–7. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200103000-00012. [see comments] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curtsinger LJ, et al. Association of cytomegalovirus infection with increased morbidity is independent of transfusion. The American Journal of Surgery. 1989;158(6):606–611. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(89)90204-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Papazian L, et al. Cytomegalovirus. An unexpected cause of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(2):280–7. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199602000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mera JR, et al. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia in adult nontransplantation patients with cancer: review of 20 cases occurring from 1964 through 1990. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 1996;22(6):1046–50. doi: 10.1093/clinids/22.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Heininger A, et al. Disseminated fatal human cytomegalovirus disease after severe trauma. Critical Care Medicine. 2000;28(2):563–6. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Toorkey CB, Carrigan DR. Immunohistochemical detection of an immediate early antigen of human cytomegalovirus in normal tissues. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1989;160(5):741–51. doi: 10.1093/infdis/160.5.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cushing D, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus and Cytomegalovirus Excretion Associated with Increased Ventilator Days in Trauma Patients. Journal of Trauma. 1993;25(1):161. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bevan IS, Sammons CC, Sweet C. Investigation of murine cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation in mice using viral mutants and the polymerase chain reaction. Journal of Medical Virology. 1996;48(4):308–20. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9071(199604)48:4<308::AID-JMV3>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Furrarah AM, Sweet C. Studies of the pathogenesis of wild-type virus and six temperature-sensitive mutants of mouse cytomegalovirus. Journal of Medical Virology. 1994;43(4):317–30. doi: 10.1002/jmv.1890430402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cook C, et al. Intra-abdominal Bacterial Infection Reactivates Latent Pulmonary Cytomegalovirus in Immunocompetent Mice. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002;185:1395–1400. doi: 10.1086/340508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henson D, Smith RD, Gehrke J. Non-fatal mouse cytomegalovirus hepatitis. Combined morphologic, virologic and immunologic observations. American Journal of Pathology. 1966;49(5):871–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Collins T, Pomeroy C, Jordan MC. Detection of latent cytomegalovirus DNA in diverse organs of mice. Journal of Infectious Diseases. 1993;168(3):725–9. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.3.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Balthesen M, Messerle M, Reddehase MJ. Lungs are a major organ site of cytomegalovirus latency and recurrence. Journal of Virology. 1993;67(9):5360–6. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.9.5360-5366.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kurz S, et al. Latency versus persistence or intermittent recurrences: evidence for a latent state of murine cytomegalovirus in the lungs. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(4):2980–7. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2980-2987.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kurz SK, et al. Focal transcriptional activity of murine cytomegalovirus during latency in the lungs. Journal of Virology. 1999;73(1):482–94. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.1.482-494.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Holtappels R, et al. Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus in the Lungs: Relative but Not Absolute Immunodominance of the Immediate-Early 1 Nonapeptide during the Antiviral Cytolytic T-Lymphocyte Response in Pulmonary Infiltrates. J Virol. 1998;72(9):7201–7212. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7201-7212.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simon CO, et al. Role for Tumor Necrosis Factor Alpha in Murine Cytomegalovirus Transcriptional Reactivation in Latently Infected Lungs. J Virol. 2005;79(1):326–340. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.1.326-340.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reddehase MJ, Podlech J, Grzimek NK. Mouse models of cytomegalovirus latency: overview. Journal of Clinical Virology. 2002;25(Suppl 2):S23–36. doi: 10.1016/s1386-6532(02)00087-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baker CC, et al. Evaluation of factors affecting mortality rate after sepsis in a murine cecal ligation and puncture model. Surgery. 1983;94(2):331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duan J, et al. Dose and duration-dependence of ganciclovir treatment against murine cytomegalovirus infection in severe combined immunodeficient mice. Antiviral Research. 1998;39(3):189–97. doi: 10.1016/s0166-3542(98)00038-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rubin RH, et al. Combined antibody and ganciclovir treatment of murine cytomegalovirus-infected normal and immunosuppressed BALB/c mice. Antimicrobial Agents & Chemotherapy. 1989;33(11):1975–9. doi: 10.1128/aac.33.11.1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Salkowski CA, et al. Pulmonary and hepatic gene expression following cecal ligation and puncture: monophosphoryl lipid A prophylaxis attenuates sepsis-induced cytokine and chemokine expression and neutrophil infiltration. Infection & Immunity. 1998;66(8):3569–78. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.8.3569-3578.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang S, et al. Expression of macrophage inflammatory protein-2 and KC mRNA in pulmonary inflammation. American Journal of Pathology. 1992;141(4):981–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsujimoto H, et al. Role of macrophage inflammatory protein 2 in acute lung injury in murine peritonitis. Journal of Surgical Research. 2002;103(1):61–7. doi: 10.1006/jsre.2001.6325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mercer-Jones MA, et al. The pulmonary inflammatory response to experimental fecal peritonitis: relative roles of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and endotoxin. Inflammation. 1997;21(4):401–17. doi: 10.1023/a:1027366403913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sime PJ, et al. Transfer of Tumor Necrosis Factor-{alpha} to Rat Lung Induces Severe Pulmonary Inflammation and Patchy Interstitial Fibrogenesis with Induction of Transforming Growth Factor-β1 and Myofibroblasts. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(3):825–832. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65624-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Warshamana GS, Corti M, Brody AR. TNF-alpha, PDGF, and TGF-beta(1) expression by primary mouse bronchiolar-alveolar epithelial and mesenchymal cells: tnf-alpha induces TGF-beta(1) Experimental & Molecular Pathology. 2001;71(1):13–33. doi: 10.1006/exmp.2001.2376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ayala A, et al. Immune depression in polymicrobial sepsis: the role of necrotic (injured) tissue and endotoxin. Critical Care Medicine. 2000;28(8):2949–55. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200008000-00044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ayala A, I, Chaudry H. Immune dysfunction in murine polymicrobial sepsis: mediators, macrophages, lymphocytes and apoptosis. Shock. 1996;6(Suppl 1):S27–38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ebong SJ, et al. Immunopathologic responses to non-lethal sepsis. Shock. 1999;12(2):118–26. doi: 10.1097/00024382-199908000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munford RS, Pugin J. Normal responses to injury prevent systemic inflammation and can be immunosuppressive. American Journal of Respiratory & Critical Care Medicine. 2001;163(2):316–21. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.2.2007102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Podlech J, et al. Murine model of interstitial cytomegalovirus pneumonia in syngeneic bone marrow transplantation: persistence of protective pulmonary CD8-T-cell infiltrates after clearance of acute infection. Journal of Virology. 2000;74(16):7496–507. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.16.7496-7507.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reddehase MJ, et al. The conditions of primary infection define the load of latent viral genome in organs and the risk of recurrent cytomegalovirus disease. Journal of Experimental Medicine. 1994;179(1):185–93. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Murayama T, et al. The immediate early gene 1 product of human cytomegalovirus is sufficient for up-regulation of interleukin-8 gene expression. Biochemical & Biophysical Research Communications. 2000;279(1):298–304. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Geist LJ, et al. Cytomegalovirus modulates transcription factors necessary for the activation of the tumor necrosis factor-alpha promoter. American Journal of Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology. 1997;16(1):31–7. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.16.1.8998076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gribaudo G, et al. The murine cytomegalovirus immediate-early 1 protein stimulates NF-kappa B activity by transactivating the NF-kappa B p105/p50 promoter. Virus Research. 1996;45(1):15–27. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(96)01356-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yurochko AD, et al. The human cytomegalovirus UL55 (gB) and UL75 (gH) glycoprotein ligands initiate the rapid activation of Sp1 and NF-kappaB during infection. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(7):5051–9. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5051-5059.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yurochko AD, et al. Human cytomegalovirus upregulates NF-kappa B activity by transactivating the NF-kappa B p105/p50 and p65 promoters. Journal of Virology. 1995;69(9):5391–400. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5391-5400.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yurochko AD, et al. Induction of the transcription factor Sp1 during human cytomegalovirus infection mediates upregulation of the p65 and p105/p50 NF-kappaB promoters. Journal of Virology. 1997;71(6):4638–48. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4638-4648.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kowalik TF, et al. Multiple mechanisms are implicated in the regulation of NF-kappa B activity during human cytomegalovirus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1993;90(3):1107–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.3.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yerkovich ST, et al. The roles of tumour necrosis factor-alpha, interleukin-1 and interleukin-12 in murine cytomegalovirus infection. Immunology. 1997;91(1):45–52. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.00226.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koffron A, et al. Immunosuppression is not required for reactivation of latent murine cytomegalovirus. Transplantation Proceedings. 1999;31(1–2):1395–6. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(98)02041-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Docke WD, et al. Cytomegalovirus reactivation and tumour necrosis factor. Lancet. 1994;343(8892):268–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91116-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thrall RS, et al. Role of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the spontaneous development of pulmonary fibrosis in viable motheaten mutant mice. American Journal of Pathology. 1997;151(5):1303–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu JY, et al. TNF-{alpha} Receptor Knockout Mice Are Protected from the Fibroproliferative Effects of Inhaled Asbestos Fibers. Am J Pathol. 1998;153(6):1839–1847. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65698-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Piguet PF, et al. Expression and localization of tumor necrosis factor-alpha and its mRNA in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. American Journal of Pathology. 1993;143(3):651–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huaux F, et al. Soluble Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptors p55 and p75 and Interleukin-10 Downregulate TNF-alpha Activity during the Lung Response to Silica Particles in NMRI Mice. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1999;21(1):137–145. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.21.1.3570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu JY, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta(1) overexpression in tumor necrosis factor-alpha receptor knockout mice induces fibroproliferative lung disease. American Journal of Respiratory Cell & Molecular Biology. 2001;25(1):3–7. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.25.1.4481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sime PJ, et al. Adenovector-mediated Gene Transfer of Active Transforming Growth Factor-beta 1 Induces Prolonged Severe Fibrosis in Rat Lung. J Clin Invest. 1997;100(4):768–776. doi: 10.1172/JCI119590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bruynseels P, et al. Herpes simplex virus in the respiratory tract of critical care patients: a prospective study. Lancet. 2003;362(9395):1536–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14740-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]