Abstract

Neuronal loss is a key component of fetal alcohol syndrome pathophysiology. Therefore, identification of molecules and signaling pathways that ameliorate alcohol-induced neuronal death is important. We have previously reported that neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) can protect developing cerebellar granule neurons (CGN) against alcohol-induced death both in vitro and in vivo. However, the upstream signal controlling nNOS expression in CGN is unknown. Activated cAMP response element binding protein (CREB) has been strongly linked to the survival of multiple cell types, including CGN. Furthermore, the promoter of the nNOS gene contains two cAMP response elements (CRE). Using cultures of CGN, we tested the hypothesis that cAMP mediates nNOS activation and the protective effect of nNOS against alcohol-induced cell death. Forskolin, an activator of the cAMP pathway, stimulated expression of a reporter gene under the control of the nNOS promoter, and this stimulation was substantially reduced when the two CREs were mutated. Forskolin increased nNOS mRNA levels several-fold, increased production of nitric oxide, and abolished alcohol’s toxic effect in wild type CGN. Furthermore, forskolin’s protective effect was substantially reduced in CGN cultures genetically deficient for nNOS (from nNOS−/− mice). Delivery of nNOS cDNA using a replication-deficient adenoviral vector into nNOS−/− CGN abolished alcohol-induced neuronal death. In addition, over-expression of nNOS in wild type CGN ameliorated alcohol-induced cell death. These results indicate that the neuroprotective effect of the cAMP pathway is mediated, in part, by the pathway’s downstream target, the nNOS gene.

Keywords: fetal alcohol syndrome, fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, gene therapy, CREB, neuroprotection, nNOS, ethanol

1. INTRODUCTION

As a leading cause of mental retardation, fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) is a major public health concern. While alcohol adversely affects a variety of molecular and cellular processes within the developing brain, neuronal death is one of alcohol’s most prominent neuropathologic effects. This neuronal loss contributes to microencephaly in children with FAS and is linked to the dyscoordination (Thomas et al., 1998), reduced seizure thresholds (Bonthius et al., 2001), and learning deficits (Goodlett, 1992) in experimental animals exposed to alcohol during brain development. Thus, neuronal death is a key component of FAS pathogenesis, and identification of molecules or signaling pathways that can reduce neuronal vulnerability to alcohol-induced death is critically important.

One such pathway that may limit alcohol-induced neuronal death is the cyclic AMP (cAMP) signaling pathway. cAMP signals many of its effects by activating cAMP response element binding protein (CREB), a transcription factor that plays a key role in the survival of multiple cell types, including neurons (Riccio et al., 1999; Walton et al., 1999; Monti et al., 2002). Mouse neurons lacking CREB function degenerate in both the peripheral (Lonze and Ginty, 2002) and central (Mantamadiotis et al., 2002) nervous systems, thus demonstrating the importance of the cAMP pathway to neuronal survival. The principal goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that the cAMP signaling pathway can protect neurons against alcohol-induced cell death.

Nitric oxide (NO) is an endogenously produced gaseous molecule that can protect developing neurons against alcohol's toxic effects. Treatment of cerebellar granule neuron (CGN) cultures with agents that increase NO production, such as NMDA, protects the cultures against alcohol-induced death (Bhave and Hoffman, 1997; Pantazis et al., 1993, 1995; Hutton Kehrberg et al., 2005). Likewise, treatment of CGN cultures with agents that inhibit NO synthesis renders the cultures more vulnerable to alcohol toxicity (Pantazis et al, 1998). The enzyme that synthesizes NO within neurons is neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). We have shown previously that mice genetically deficient for nNOS (nNOS−/− mice) have an enhanced vulnerability to alcohol-induced microencephaly and neuronal loss, thus confirming an important role for NO in neuroprotection against alcohol in vivo (Bonthius et al., 2002; 2006).

Identification of the upstream signal regulating nNOS expression is critically important for understanding the cascade of events leading to NO-mediated neuroprotection against alcohol. Because the nNOS gene promoter contains two cAMP response elements (Sasaki et al., 2000) with 100% identity to the consensus cAMP response element sequence (Mayr and Montminy , 2001), we hypothesize that the cAMP signaling pathway plays a role in regulating nNOS gene expression. Thus, the second goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that the nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP signaling pathway and that nNOS mediates the neuroprotective effect of the cAMP signaling pathway.

Genetic factors influence fetal vulnerability to alcohol teratogenesis (Goodlett et al., 2005), possibly by a mechanism involving genetic differences in neuroprotective pathways. Gene therapy techniques provide a means of introducing neuroprotective agents into neurons, thereby potentially ameliorating alcohol’s harmful effects. The third goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that delivery of the nNOS gene via viral gene therapy vectors can diminish neuronal vulnerability to alcohol-induced death.

2. RESULTS

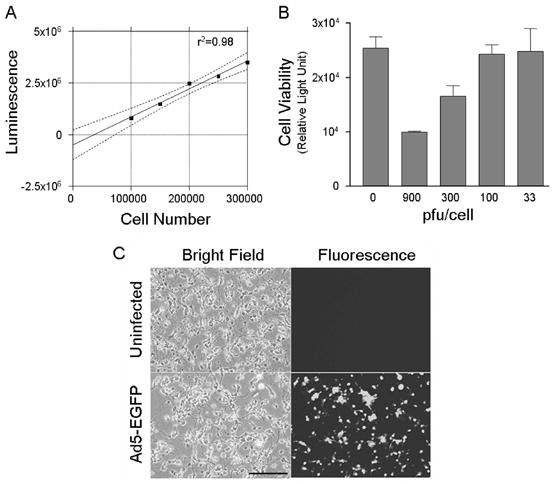

2.1. Adenoviral vectors can deliver genes into cultured mouse CGN

We tested the hypothesis that stimulation of the cAMP pathway protects CGN against alcohol-induced cell loss and that a key downstream molecule mediating this neuroprotective effect is neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS). Since these studies required efficient gene delivery into CGN, we first determined whether a reporter vector (adenovirus carrying cDNA for enhanced green fluorescent protein, Ad5-EGFP) could introduce EGFP into CGN. As a first step, we infected CGN cultures with a variety of titers (0 to 900 pfu/cell serial dilutions) of an empty adenoviral control vector (Ad5-Bgl II) carrying only a Bgl II site to determine a non-toxic viral titer for the subsequent induction experiments. Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter Glow Assay (Promega), in which luminescence increased linearly with increasing cell number within our experimental conditions (fig. 1A). Adenoviral titers of 300 pfu per cell and greater produced substantial toxicity, which increased with increasing titer (fig 1B). In contrast, titers of 100 pfu per cell and below induced only minimal toxicity. When infected with Ad5-EGFP at 100 pfu per cell, more than 90% of the cells were transduced by 48 hours post-infection (fig. 1C). The infected cells appeared healthy and had a normal morphology and density (fig. 1C). This demonstrates that adenovirus-based gene therapy vectors can be used to deliver genes into CGN.

Figure 1.

Adenoviral vectors can deliver genes to cultured cerebellar granule neurons (CGN). A. Cell viability assay, CellTiter Glow, showed a linear correlation between measured luminescence and the number of cultured cells. Thus, the assay could be used to determine cell viability following adenoviral infection. B. At an MOI of 300 and greater, adenoviral infection induced substantial loss of cell viability. However, at 100 pfu per cell and below, adenoviral infection produced no evident toxicity. Thus, MOI of 100 pfu per cell was chosen for the induction experiments. C. CGN were infected with an adenoviral vector carrying coding sequences of enhanced green fluorescent protein (Ad5-EGFP) at an MOI of 100 pfu per cell, and the cultures were photographed with a confocal microscope 48 hours after the infection. A high proportion of the cells were infected with the adenovirus. Uninfected cells served as the negative control for the fluorescence signal and for possible toxicity induced by the viral vector. No toxicity from the viral vector was evident. Thus, adenoviral vectors can infect CGN and express the genes that the viral vectors carry. The experiment was repeated with wild type and nNOS−/− CGN cultures three times with similar results. Magnification bar in C = 100 μm.

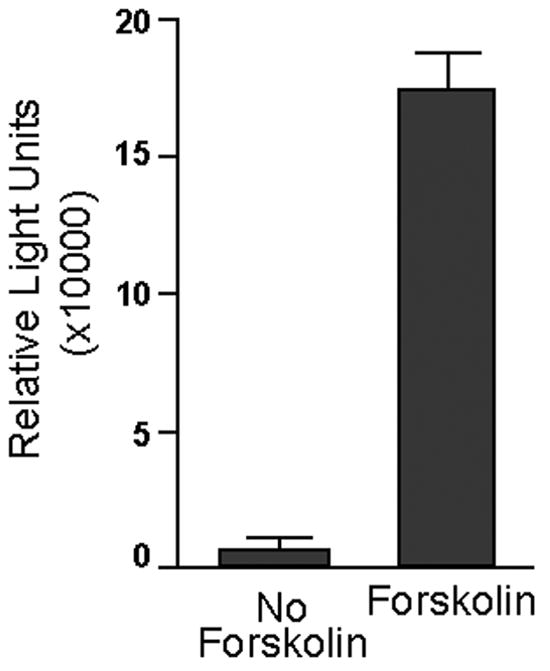

2.2. CGN cultures have a functional cAMP pathway that protects the cells against alcohol-induced death via an nNOS-dependent mechanism

We utilized an adenoviral reporter vector containing a luciferase gene coding region under the control of a basic promoter with six tandem copies of the CRE consensus binding sequence (Ad5-CRE-Luc) to establish the presence of an active cAMP pathway within CGN cultures. As shown in figure 2, forskolin, an activator of the cAMP pathway, substantially upregulated (by 17-fold) expression of the luciferase gene, relative to CGN cultures that did not receive forskolin. Thus, CGN possess a functional cAMP pathway.

Figure 2.

Forskolin activates the cAMP pathway in CGN. CGN cultures were infected with an adenoviral reporter vector containing a luciferase gene coding region under the control of a basic promoter with six tandem copies of the CRE consensus binding sequence (Ad5-CRE-Luc). Twenty-four hours after the infection, the treatment wells received forskolin (10 μM). At 48 hours, the cells were harvested, and luciferase activity was determined. Luciferase activity, which reflects cAMP pathway activity, is expressed as relative light units (RLU) per microgram of protein. Data represent the mean of three independent experiments. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. Forskolin led to a 17-fold increase in luciferase activity, indicating that CGN possess a functional cAMP pathway.

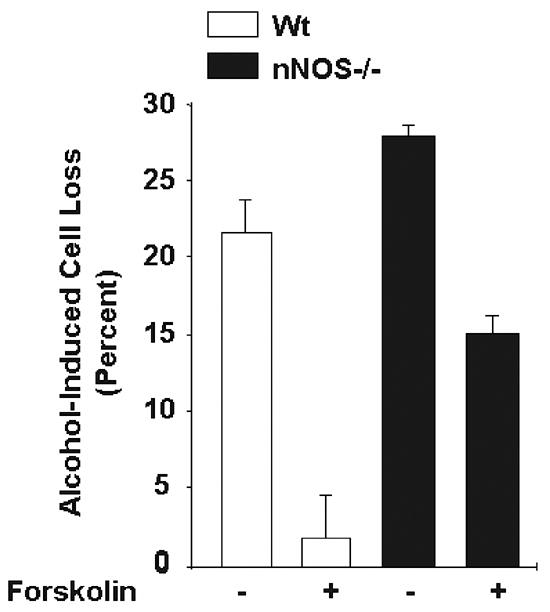

We next examined whether activation of the cAMP pathway can protect CGN against alcohol-induced neuronal death. We tested the protective effect of forskolin in wild type cells and in cells genetically deficient for nNOS (from nNOS−/− mice). If cAMP signals its neuroprotective effect via nNOS, then the protective effect should be reduced or absent in cells genetically lacking nNOS. We treated CGN cultures from wild type and nNOS−/− mice with forskolin (0 μM or 10 μM) followed by alcohol (0 mg/dl or 400 mg/dl), and determined rates of alcohol-induced cell death.

Figure 3 shows the percent cell losses for each of the treatment groups, relative to the control (no-alcohol and no-forskolin) group. Alcohol alone, in the absence of forskolin, induced a substantial toxic effect in the wild type and nNOS−/− cultures. However, the ANOVA revealed a significant effect of genotype [F(1,8)=28.98; p<0.001], reflecting greater alcohol-induced cell losses in the nNOS−/− strain. The ANOVA also revealed a significant effect of forskolin treatment [F(1,8)=59.2; p<0.001], reflecting forskolin's protective effect against alcohol in cells derived from either strain. Most importantly, there was a significant genotype x forskolin interaction [F(1,8)=4.92; p<0.05], demonstrating that forskolin's protective effect depended on genotype. Post-hoc analyses revealed that all four of the treatment groups shown in figure 3 were significantly different from each other (p<0.05).

Figure 3.

Forskolin, a cAMP pathway inducer, protected CGN cultures against alcohol-induced cell death to a greater extent in wild type cells than in cells deficient for nNOS. Cerebellar granule cultures were established from wild type and nNOS−/− mice. Twenty-four hours after establishment, the cultures were treated with forskolin (0 or 10 μM) for 24 hours. The cells were then exposed to ethanol (0 or 400 mg/dl) and forskolin for an additional 24 hours, and the percent of alcohol-induced cell death was determined using the trypan blue staining method. Data represent the mean of at least three different litters from each genetic background. Error bars represent standard error of the mean. All treatment groups were significantly different from each other (p<0.05). In the absence of forskolin, alcohol-induced cell losses were greater in the nNOS−/− mice than in the wild type mice. Forskolin reduced alcohol toxicity in both strains, but more effectively in the wild type cells than in the nNOS−/− cells. Thus, stimulation of the cAMP pathway exerts a neuroprotective effect against alcohol, and this protective effect is linked to the expression of nNOS.

Forskolin was more neuroprotective against alcohol-induced cell loss in the wild type cultures than in the nNOS−/− cultures. In the wild type cultures, forskolin substantially reduced alcohol-induced cell losses (21.4% cell loss without forskolin to 1.8% with forskolin). While in the nNOS−/− cultures, forskolin's protective effect was far more modest (28.6% cell loss without forskolin to 16.7% with forskolin). Thus, activation of the cAMP pathway with forskolin had a strong neuroprotective effect against alcohol toxicity in CGN, and absence of the nNOS gene diminished this protective effect.

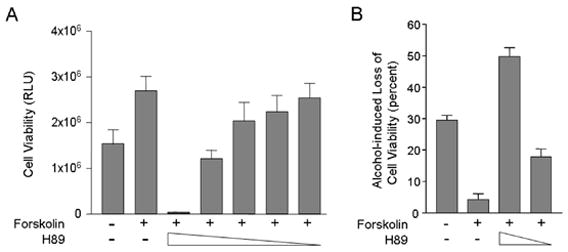

2.3. Forskolin-mediated protection of CGN against alcohol toxicity is PKA-dependent

The above results demonstrate that forskolin exerts a neuroprotective effect against alcohol toxicity. We hypothesize that it does so by stimulating the cAMP pathway, However, forskolin could act through other mechanisms. In the cAMP signaling pathway, cAMP binds to protein kinase A (PKA). Thus, if forskolin’s protective effect involves the cAMP pathway, then this effect should be reduced if PKA’s actions are blocked.

We treated CGN cultures from wild type mice with forskolin in the absence or presence of the selective PKA inhibitor, H89. As shown in figure 4A, in the absence of H89, forskolin substantially increased cell viability. However, forskolin's trophic effect was diminished by H89, in a dose-dependent manner. At high concentrations, H89 not only abolished forskolin’s neurotrophic effect, but also reduced cell viability to much lower levels than in untreated cultures, thus indicating a vital role for active PKA in the survival of CGN.

Figure 4.

Forskolin’s neurotrophic effect and neuroprotective effect against alcohol toxicity are PKA-dependent. A. CGN cultures were treated with forskolin in the presence of the selective PKA inhibitor, H89 (concentrations ranging from 0 to 10 μM). Forskolin alone exhibited a neurotrophic effect and substantially increased cell viability. H89 at the highest concentration not only abolished this effect, but reduced cell viability drastically. As the concentration of H89 decreased, forskolin’s effect was reinstated. Thus, selective inhibition of PKA blocked the neurotrophic effect of forskolin. B. CGN cultures exposed to alcohol (0 or 400 mg/dl) were treated with forskolin (0 or 10μM) in the absence or presence of H89 (0, 5, or 10μM). Alcohol-induced reductions in cell viability were determined. Alcohol alone (in the absence of forskolin or H89) substantially reduced cell viability. Forskolin protected the cells against alcohol toxicity. PKA inhibition by H89 reduced forskolin’s protective effect against alcohol toxicity in a dose-dependent fashion. Thus, selective inhibition of PKA blocked the neuroprotective effect of forskolin.

We next examined the effect of H89 on forskolin’s neuroprotective function against alcohol toxicity (fig. 4B). Alcohol alone caused a 30 percent loss in cell viability. In the absence of H89, forskolin exerted a neuroprotective effect and reduced cell losses to 4.2 percent. At a relatively low concentration, H89 attenuated forskolin’s neuroprotective effect, and cell losses rose to 18 percent. At a higher concentration, H89 completely blocked forskolin’s neuroprotective effect and cell losses rose to almost 50 percent, which exceeded those observed with alcohol alone. Thus, the neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects of forskolin are PKA-dependent events in CGN. These findings strongly suggest that forskolin promotes cell survival by stimulating the cAMP pathway.

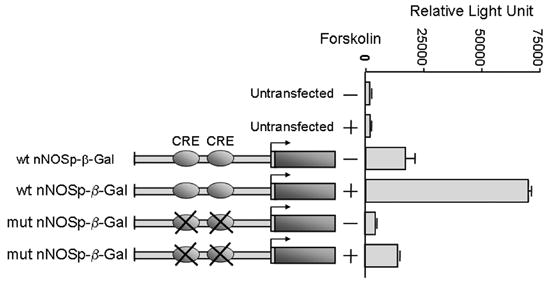

2.4. Forskolin activates a nNOS-promoter construct containing CRE

The nNOS gene promoter contains two cAMP response elements (Sasaki et al., 2000) with 100% identity to the consensus cAMP response element sequence (Mayr and Montminy, 2001). Therefore, we hypothesized that nNOS is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway and that activation of the pathway induces nNOS gene expression, thus protecting CGN against alcohol toxicity. To test the hypothesis that the nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP signaling pathway, we studied activity of the nNOS promoter in response to forskolin-mediated activation of the cAMP pathway. In these transfection experiments, we used a promoter construct composed of 854-bp of the nNOS gene promoter carrying two CRE fused to the coding region of the beta-galactosidase (β-gal) gene and a mutated version of the same construct carrying mutations within both CRE (Sasaki et al., 2000). Initially, we transfected these plasmid vector constructs into cerebellar granule cultures using lipid-based transfection reagents. However due to toxicity of the transfection process and low transfection efficiency in surviving CGN, we conducted the promoter analysis studies in the SKNSH neuroblastoma cell line. We chose SKNSH neuroblastoma cells as an alternative to CGN cultures because SKNSH cells are transfected by plasmid-based vectors with a high efficiency. SKNSH cells are relevant to these studies because, like CGN, they are of neuronal origin and vulnerable to alcohol-induced cell death in a dose dependent manner (McAlhany, et al., 2000; McAlhany et al., 1997).

As shown in figure 5, untransfected SKNSH cells exhibited only a low level of β-gal activity in the absence of forskolin. Enzyme activity remained low even after forskolin treatment of the untransfected cells, reflecting the low background level of forskolin-inducible β-gal activity in the SKNSH cell line. When the cells were transfected with the wild type promoter construct, a moderate increase in β-gal activity was detected in the absence of forskolin, indicating that an active cAMP pathway exists in SKNSH cells, even without exogenous stimulation. However, forskolin substantially stimulated expression of the wild type nNOS promoter, increasing the level of β-gal activity four-fold, relative to the un-induced state (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

The nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway. Forskolin induced expression of the nNOS promoter in human neuroblastoma cells. Each nNOS promoter-beta galactosidase plasmid was introduced into SKNSH cells, and the beta galactosidase activity expressed from each construct was measured 48 hours after transfection. Forskolin was added to corresponding cultures 12 hours prior to harvesting. For all transfection assays, at least three independent experiments were performed. Beta galactosidase activity is shown with standard deviation as error bars. Forskolin stimulated expression of the nNOS promoter-reporter construct, and this stimulation was substantially reduced when the two CRE sites were mutated.

In the absence of forskolin, activity of the nNOS promoter construct carrying CRE mutations was much lower than the activity of wild type promoter and was similar to the background level in untransfected cells. This suggests that the two CRE within the 5’-flanking and promoter region of the nNOS gene play an important role in the expression of nNOS in the un-induced (no forskolin) SKNSH cultures. Treatment with forskolin slightly increased the activity of the mutant promoter, but this modest increase was in marked contrast to the large forskolin-induced increase in activity of the wild type promoter. These results suggest that the CRE sites within the nNOS promoter play an important role in the expression of the nNOS gene.

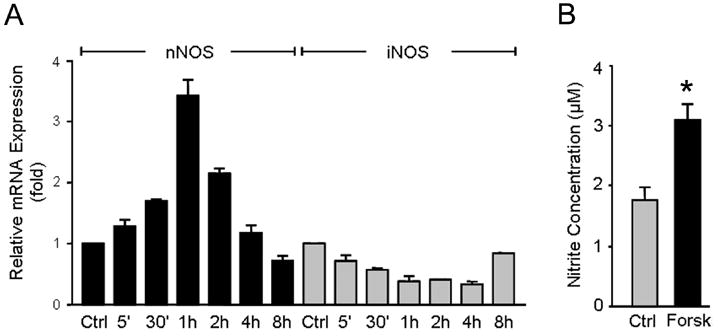

2.5. Forskolin upregulates expression of the nNOS gene in CGN cultures

To provide further evidence that the nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway, we treated CGN cultures with forskolin and measured the temporal expression of the nNOS gene with real time quantitative PCR assay. As shown in figure 6A, forskolin induced expression of the nNOS gene in a time-dependent manner. Forskolin induced expression of the nNOS gene as early as 5 min following treatment. The level of nNOS mRNA continued to increase for one hour following forskolin treatment and then decreased, reaching control (no forskolin) levels by 8 h (figure 6A).

Figure 6.

Forskolin increases the expression and activity of the endogenous nNOS gene, but not iNOS gene, in wild type CGN cultures. A. CGN were treated with forskolin, and nNOS and iNOS gene expression levels were determined by real time quantitative PCR assay in a time course experiment. nNOS and iNOS mRNA levels are presented, relative to the levels observed in untreated CGN. Values represent the mean of two independent data points. Error bars represent SEM. B. Total nitrite levels in culture media was determined by the Griess reaction, as an indication of NOS activity. Values represent the mean of six independent data points. Error bars represent SEM. * Significantly different from control (p<0.05).

The relative nNOS expression in CGN cultures was further assessed by measuring the accumulation of nitrite (NO2−), a stable oxidized product of the released NO in the culture medium. We conducted the Griess reaction in CGN cultures in the absence or presence of forskolin stimulation. Figure 6B demonstrates the total nitrite levels. Nitrite levels were substantially greater in the cultures treated with Forskolin than in the control cultures (3.1μM v. 1.8 μM). Taken together, these expression analyses demonstrate that the nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway in CGN cultures.

Because NO can be produced not only by nNOS, but also by inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), the possibility arose that part of the generated NO in response to forskolin was due to the stimulated expression of iNOS, rather than nNOS. To determine the possible contribution of iNOS, we measured the expression of iNOS mRNA in the same samples in which nNOS mRNA was measured. As shown in Figure 6A, forskolin did not increase levels of iNOS mRNA in the CGN cultures. On the contrary, during the first 4 hours of forskolin treatment, iNOS expression was decreased, then rose slightly, but was still less than control levels at 8 hours. These expression analyses demonstrate that the nNOS gene, and not the iNOS gene, is the source of NO generation and that the nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway in CGN cultures.

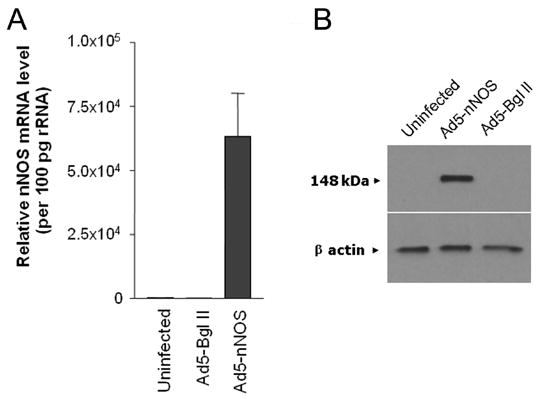

2.6. Transduction of the nNOS gene via an Ad5-nNOS viral vector protects nNOS−/− and wild type CGN cultures against alcohol-induced cell death

We have previously reported that genetic deficiency of nNOS worsens alcohol-induced microencephaly and neuronal loss both in vitro and in developing mice (Bonthius et al., 2002; Bonthius et al., 2006). This suggested that nNOS exerts a neuroprotective effect against alcohol toxicity. However, it was also possible that unforeseen secondary effects of nNOS deficiency played a role in the cells' increased vulnerability to alcohol. To address this issue, we transduced the nNOS gene into nNOS−/− CGN cultures using the Ad5-nNOS vector and assessed the alcohol vulnerability of the transduced cells. An empty vector carrying only the Bgl II restriction site was used as a negative control.

Quantitative Real Time PCR revealed that nNOS expression was undetectable in uninfected nNOS−/− CGN cultures and in nNOS−/− cultures infected with the Ad5-Bgl II control vector, indicating that the vector alone did not have a non-specific effect on nNOS gene expression (Figure 7A). In contrast, Ad5-nNOS increased nNOS expression several hundred fold (Figure 7A), indicating a successful transduction of the nNOS gene into the nNOS−/− cells with this construct. Furthermore, Western immunoblotting analysis (Figure 7B) detected a single band of appropriate molecular weight (155 kDa) in nNOS−/− cells transduced with the nNOS vector. This band was not seen in untreated cells or in cells treated with the Ad5-Bgl II (empty) vector. These results indicate the successful transduction of the nNOS gene into nNOS−/− CGN.

Figure 7.

Adenoviral delivery of nNOS to CGN cultures leads to expression of nNOS at both the mRNA and protein levels. Cerebellar granule neurons derived from mice lacking nNOS (nNOS−/−) were infected with an adenoviral vector carrying the coding region of nNOS (Ad5-nNOS). Quantitative RT-PCR and Western blot analysis were carried out to determine the expression of nNOS messenger RNA (A) and protein (B). The amount of nNOS message is shown, relative to the amount in uninfected cells. An empty adenoviral vector carrying only a Bgl II site was used as a negative control for both messenger RNA and protein detection. Beta actin served as an internal control and indicates an equal amount of protein loading in each lane.

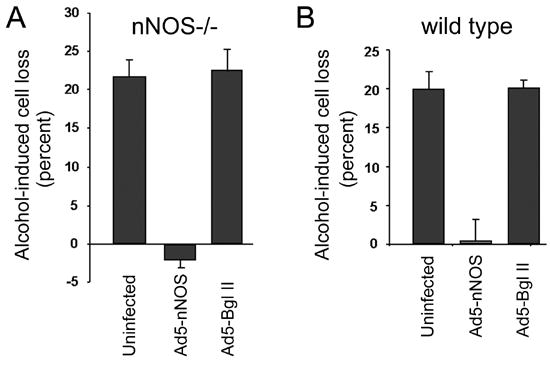

The effect of nNOS gene transduction on neuronal alcohol vulnerability is revealed in Figure 8. Alcohol (400 mg/dl) induced substantial cell death in the uninfected (no vector treatment) nNOS−/− CGN cultures (Figure 8A). A similar level of alcohol-induced cell death occurred in the cultures treated with the empty vector (Ad5-BglI), indicating that the vector alone had no effect on neuronal survival. In both groups, the percentage of cells killed by alcohol exceeded 20 percent. In contrast, when nNOS−/− CGN were infected with the Ad5-nNOS vector, cell death caused by alcohol toxicity was reduced dramatically. In fact, ectopic over-expression of nNOS in nNOS−/− cells completely eliminated alcohol-induced cell death.

Figure 8.

Delivery of nNOS via an adenoviral vector protects CGN against alcohol-Induced cell death. Cerebellar granule neurons derived from mice lacking nNOS (nNOS−/−) (A) and wild type (B) were infected either with an adenoviral vector carrying the coding region of nNOS (Ad5-nNOS) or with an empty vector (Ad5-Bgl II) 18 hours after establishment of the cultures. Treatment groups were exposed to alcohol 24 hours after the viral infection for an additional 24 hours. A. In uninfected cultures derived from mice lacking nNOS (nNOS−/−), alcohol induced a substantial amount of cell death. Delivery of nNOS via adenoviral vector blocked this toxic effect. In contrast, delivery of the empty vector (Ad5-Bgl II) had no protective effect. B. In uninfected cultures derived from wild type mice, alcohol likewise induced cell death. Delivery of nNOS via adenoviral vector also protected these cells against alcohol toxicity, as it did in nNOS−/− cells. The experiments were repeated at least three times with different litters. Error bars represent standard error of the mean.

Since wild type CGN cells are also vulnerable to alcohol-induced death, we repeated this stimulation in a separate experiment using wild type cultures (Figure 8B). We found that over-expression of nNOS in the wild type cells completely protected them against alcohol-induced cell death, as it did in the nNOS−/− cultures. The results indicate that transduction of the nNOS gene into CGN was highly effective in protecting the neurons against alcohol-induced cell death.

3. DISCUSSION

The principal goals of this study were to investigate the neuroprotective effect of cAMP pathway activation on the survival of cerebellar granule neurons exposed to alcohol and to determine whether nNOS is a downstream target gene mediating the neuroprotective effect of cAMP activation. This study yielded three important new findings. First, activation of the cAMP pathway protects cultured CGN against alcohol-induced cell death. Second, the nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway and plays a critical role in mediating the neuroprotective effect of cAMP against alcohol toxicity. Third, transduction of the nNOS gene into CGN cultures completely protects the cells against alcohol neurotoxicity. These results demonstrate that the cAMP signaling pathway can provide a powerful neuroprotective effect against alcohol toxicity by activating the nNOS gene. In addition, the results suggest that gene therapy may be a useful therapeutic approach to prevent the neuroteratogenic effects of alcohol on the developing brain.

3.1. Stimulation of the cAMP pathway protects cultured CGN against alcohol-induced death

These studies demonstrated that cultured wild type CGN possess a functional cAMP pathway and that stimulation of this pathway has both neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects in CGN cultures. The pathway's neurotrophic effect increases cell survival at baseline (in the absence of alcohol), while its neuroprotective effect reduces alcohol-induced neuronal death.

One component of the cAMP signaling pathway is protein kinase A (PKA), which is activated by increased intracellular cAMP concentrations. PKA exhibits neuroprotective effects against a variety of insults in a variety of neurons (Tanaka, 2001; Chiarini et al, 2002; Shioda et al., 2006). Our results demonstrate that PKA plays a critical role in the survival of cultured cerebellar granule neurons at baseline (in the absence of alcohol). Furthermore, we found that inhibition of PKA abolishes the protective effect of cAMP pathway stimulation against alcohol toxicity. Thus, PKA plays a critical role in CGN cell survival both in the presence and absence of alcohol.

A second component of the cAMP signaling pathway that likely plays a central role in 1the pathway’s trophic and protective effects is the transcription factor CREB (cAMP-response-element-binding-protein). CREB influences the expression of several genes by interacting with the CRE site(s) contained within the genes’ promoters. Phosphorylation is necessary for CREB to acquire its active form (Walton and Dragunow, 2000). While nonphosphorylated CREB is expressed diffusely throughout the cerebellum, phosphorylated CREB is localized to CGN (Monti et al., 2002). Activated (phosphorylated) CREB plays a key role in the survival of multiple cell types, including neurons (Monti et al., 2002; Walton et al., 1999). Activation of CREB promotes the survival of CGN within the developing cerebellum (Monti et al., 2002). Within the hippocampal formation, activated CREB protects hippocampal sub-regions against hypoxic-ischemic injury, and levels of activated CREB are correlated with resistance to injury (Schreiber and Baudry, 1995). In particular, following a hypoxic-ischemic insult, activated CREB levels are increased within the resistant dentate granule cells, but are decreased within the vulnerable CA1 pyramidal cells (Schreiber and Baudry, 1995; Walton et al., 1996). Therefore, within both the hippocampus and cerebellum, two brain regions that are particularly susceptible to alcohol toxicity during development (Bonthius and West, 1990), activated CREB plays an important role in neuronal survival.

Within the developing cerebellum, neuronal vulnerability to alcohol-induced death diminishes with time. In particular, the cerebellum is far less vulnerable to alcohol-induced neuronal losses during the second postnatal week than during the first postnatal week. This time-dependent alcohol resistance occurs both in vivo (Goodlett and Eilers, 1997) and in vitro (Bonthius et al., 2004; Hutton et al., 2005) and could be due to the maturation of intrinsic neuroprotective mechanisms within the cerebellum. A developmentally-regulated cAMP signaling pathway could be an important component in this neuroprotection. Indeed, CREB is developmentally regulated (Monti et al., 2002), with expression levels increasing substantially during the first weeks of postnatal life. Therefore, the function, topography and ontogeny of CREB all suggest that it is an important effector molecule within the cAMP signaling pathway and plays a pivotal role in the acquisition of time-dependent alcohol resistance.

3.2. The nNOS gene is a downstream target of the cAMP pathway and plays a critical role in mediating the neuroprotective effect of cAMP against alcohol toxicity

We have shown previously that nitric oxide (NO) can protect developing neurons against alcohol toxicity. Treatment of cultured CGN with NMDA, which stimulates the production of NO (Pantazis et al, 1995), or with DETA-NONOate, which serves as an NO generator (Pantazis et al, 1998), reduces alcohol-induced cell death. Conversely, treatment of cultured CGN with NAME, which inhibits NO production by nNOS, worsens alcohol-induced cell death (Bonthius et al., 2004). NO is neuroprotective against alcohol in vivo, as well. Developing mice that are genetically deficient for nNOS, and thus unable to produce NO within their neurons, have more severe alcohol-induced microencephaly and neuronal losses than do wild type mice (Bonthius et al., 2002; 2006). Furthermore, cultured CGN from these nNOS null mice have an enhanced vulnerability to alcohol-induced cell death (Bonthius et al., 2002). This enhanced vulnerability is abolished by treating the cultures with the NO generator, DETA-NONOate (unpublished observations), demonstrating that their increased susceptibility to alcohol is due to NO deficiency.

While multiple lines of evidence have suggested that nNOS is neuroprotective against alcohol, the upstream signal regulating expression of this enzyme in CGN had remained elusive. The presence of two cAMP response elements (CRE) within the nNOS gene promoter led us to hypothesize that nNOS is a downstream target of the cAMP signaling pathway. Several results reported here support this hypothesis. Forskolin-activation of the cAMP pathway induced the nNOS gene promoter, while mutation of the CRE sites substantially reduced this effect. Although forskolin slightly stimulated the mutant promoter, stimulation was far less than in the wild type promoter. Since the promoter construct is large (containing an 854-bp region with several transcription factor binding sites), the stimulation may be an effect of forskolin on other transcription factors that modulate nNOS gene expression. Sasaki and coworkers (2000) have demonstrated that the CRE mutations used in the present study abolish the binding of CREB to the CRE sites of the nNOS promoter.

Forskolin induced expression of the endogenous nNOS gene. Furthermore, activation of the cAMP pathway protected wild type neurons against alcohol-induced cell death to a much greater extent than it protected nNOS−/− neurons. These results strongly support the hypothesis that nNOS is under the control of the cAMP signaling pathway and that cAMP signals its neuroprotective effects, at least in part, via nNOS.

cAMP analogs or agents that increase intracellular cAMP concentration stimulate nNOS expression in several human cell lines, including A673 neuroepithelioma, neuroblastoma, testicular carcinoma, and a keratinocyte cell line (Boissel et al., 2004). Our results extend these previous findings by demonstrating that the same regulation occurs in primary neuronal cultures and in a different species, the mouse.

The mechanism underlying NO-mediated neuroprotection remains unclear, although accumulating evidence suggests that NO alters apoptotic pathways. NO can inhibit apoptosis in many cell types, including cerebellar granule neurons (Ciani et al., 2002b), human B lymphocytes (Mannick et al., 1994), ovarian follicles (Chun et al., 1995), splenocytes (Genaro et al., 1995), eosinophils (Beauvais et al., 1995), and endothelial cells (Dimmeler et al., 1997). Furthermore, NO affects apoptosis-related proteins. For example, NO suppresses bax and caspases in dorsal root ganglia neurons (Thippeswamy et al., 2001). Conversely, lack of NO reduces levels of the anti-apoptotic protein, bcl-2, in CGN cultures (Ciani et al., 2002a). The mechanism by which NO alters apoptosis-related proteins is unknown.

In the present study, forskolin-activation of the cAMP signaling pathway exerted a greater neuroprotective effect in wild type neurons than in nNOS−/− neurons. However, even in the nNOS−/− neurons, the cAMP pathway led to some neuroprotection. This suggests that, while nNOS is a major target of the cAMP signaling pathway, other targets with neuroprotective effects exist, as well. Indeed, we have demonstrated previously that several growth factors, including brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and Insulin-Like Growth Factor I (IGF-1) protect CGN against alcohol toxicity (Luo et al, 1997; Bonthius et al., 2003). Like nNOS, the BDNF and IGF-1 genes contain CRE sites within their promoters, suggesting involvement of the cAMP pathway in regulating their expression and neuroprotective function.

Our results demonstrate that the cAMP pathway regulates nNOS expression. Conversely, nNOS can regulate CREB activity (Ciani et al., 2002a; Riccio et al., 2006). Thus, CREB and nNOS mutually regulate each other. These observations demonstrate the remarkable complexity of cellular signaling pathways and molecular mechanisms regulating the dynamic interaction between NO and CREB.

3.3. Transduction of the nNOS gene into cultured CGN with Ad5-nNOS prevents alcohol-induced cell death

Based on our previous observation that nNOS protects CGN cultures against alcohol-induced cell death (Bonthius et al., 2002) and that nNOS−/− mice have an enhanced vulnerability to alcohol-induced microencephaly and neuronal loss (Bonthius et al., 2002; Bonthius et al, 2006), we hypothesized that delivery of the nNOS gene into CGN derived from nNOS−/− mice could protect the neurons against alcohol toxicity. The results confirmed this hypothesis. Delivery of the nNOS gene into CGN lacking the nNOS gene protected these neurons against alcohol toxicity and reduced alcohol-induced cell death dramatically. Furthermore, overexpression of nNOS in wild type CGN can also provide neuroprotection. In wild type cultures, nNOS overexpression completely eliminated alcohol-induced cell death, as it did in nNOS−/− cultures. This finding that delivery of a neuroprotective gene can protect not only cells that lack the gene, but also cells that possess it, underlines the importance of and complex interactions among gene expression levels, developmental stage of the cells and organism, and timing of the alcohol challenge.

Among children prenatally exposed to alcohol, there is a wide range in the severity of neurological and behavioral sequelae. Some have structurally normal brains and no behavioral deficits, while others have severe microencephaly accompanied by mental retardation, epilepsy, and attention deficits. These disparities in outcome cannot be attributed solely to differences in alcohol exposure, since fetuses exposed to similar quantities of alcohol can differ substantially in severity of brain dysfunction (Sokol et al., 1980). The disparities may be due to differences in neuroprotective pathways, such as the cAMP- NO pathway. Fetuses with highly functional neuroprotective pathways may avoid the detrimental effects of alcohol, while fetuses with less effective pathways may be particularly susceptible to alcohol-induced brain injury. If this is the case, then the possibility arises that delivery of neuroprotective genes to fetuses that lack them could protect the fetuses against alcohol-induced injury.

4. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

4.1. Establishment of CGN cultures

By homologous recombination, Huang and co-workers (1993) generated the nNOS−/− strain of mice utilized in this study. Using RT-PCR, we have verified that the homozygous nNOS−/− mice do not express nNOS (Bonthius et al., 2002). Low levels of residual NOS activity remain in the brains of these mice, presumably due to non-neuronal NOS isoforms associated with cerebral vasculature (Huang et al., 1993).

The nNOS−/− mice were originally produced on a background of 129SVJ and B6 mouse strains. Therefore, for the wild type control, we utilized the F2 offspring of 129SVJ x B6 matings. These animals are recognized as appropriate controls for the nNOS−/− line (Huang et al., 1993). Breeding pairs of nNOS−/− and wild type mice were obtained from Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). The mice were bred at the University of Iowa Animal Care Facility. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at the University of Iowa approved all of the procedures employed in this study.

CGN cultures were established from 9-day-old mouse pups from the wild type or nNOS−/− line. The cerebella from all pups of each litter were combined and dissociated to yield a pool of cells. The CGN were plated into 6-well or 96-well tissue culture trays (pre-coated with poly-D-lysine) at a density of 1 x 106 or 5 x 105 cells/well, respectively. Cells were maintained in a defined, serum-free medium (Bonthius et al., 2003). A physiological concentration of potassium (5mM) was used throughout this study because the experiments included only short-term CGN cultures (less than 4 days in vitro). Although a high depolarizing concentration (25mM) of potassium enhances cell survival in long-term CGN cultures (4 days in vitro or greater), cell survival in short-term cultures is not improved by high potassium concentrations (our unpublished data).

4.2 Assessment of forskolin’s neuroprotective effect against alcohol

Cultures from wild type and nNOS−/− mice were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The cultures were then treated with forskolin (final concentration of 0 μM or 10 μM) for 24 hours before exposure to ethanol (0 or 400 mg/dl) and forskolin for an additional 24 hours. The number of viable granule cells in each well was determined. The cells were counted on a hemocytometer using exclusion of trypan blue as an indicator of cell viability. To calculate the percentage of cells killed by alcohol in each condition, the number of viable cells in each alcohol-exposed group was subtracted from the mean number of viable cells in the no-alcohol group, then divided by the mean number of viable cells in the no-alcohol group. The percent cell loss data were analyzed by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with genotype (wild type versus nNOS−/−) and forskolin treatment (with forskolin or without forskolin) as the two grouping factors. Specific post hoc between-group comparisons were analyzed by the Newman-Keuls multiple comparisons procedure.

4.3. Assessment of selective PKA inhibition on forskolin-mediated neuroprotection

CGN cultures from wild type mice were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours, then treated for 48 hours with forskolin (final concentration 0.0 or 10.0 μM) and H89, a selective PKA inhibitor at a variety of concentrations (0.0, 0.65, 1.25, 2.5, 5.0 or 10.0 μM). Cell viability was determined with the CellTiterGlow assay (Promega). CGN were plated on a 96-well plate in 300 μl of media and incubated at 37°C. After the experimental period, just before the assay, the cultures were transferred to room temperature for 30 min. 200 μl of media was removed from the wells, leaving approximately 100 μl of media in each of the wells. 100 μl of assay substrate was then added to each well. Plate contents were mixed on an orbital shaker for 2 min. After 10 min of incubation at room temperature, luminescence was measured in a Lumat LB9501 luminometer (Berthold).

To determine the effect of the selective PKA blocker, H89, on forskolin’s protective function against alcohol toxicity, CGN cultures from wild type mice were treated with forskolin (0.0 or 10.0 μM) alone or in combination with H89 (5.0 or 10.0 μM) 24 hours after establishment of the cultures. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours.

Ethanol (0 or 400 mg/dl) was then added to the cultures. 24 hours later (72 hours after culture establishment), cell viability was determined, as described above. Percent cell loss due to alcohol exposure was calculated by comparing the luminometer readings (relative light unit) in the alcohol-exposed wells with the readings from the matching no-alcohol wells.

4.4. Adenoviral infection

Adenoviral infection efficiency was assessed through the use of an adenovirus encoding enhanced green fluorescent protein (Ad5-EGFP). Toxicity of the adenoviral infection in cerebellar granule neurons was assessed using the CellTiter Glow Assay (Promega). First, different quantities of CGN (100K–300K with 50K intervals) were plated on a 96-well plate. The cultures were then incubated at 37°C for 24 hours and the CellTiter Glow assay was carried out as described above. The assay showed a linear correlation (r2=0.98) within our experimental conditions. To determine adenoviral infection efficiency, 5x104 CGN were plated onto 24-well plates and permitted to adhere overnight before addition of adenoviral vectors. Immediately prior to infection, the cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). The viral vector (Ad5-EGFP) was then added (100 pfu/cell) in serum-free culture medium. Forty-eight hours after the infection, transduction was evaluated by visual observation of the fluorescing protein, and the cultures were photographed using a con-focal microscope.

4.5. Alcohol vulnerability of CGN infected with adenoviral vectors

Vulnerability to alcohol-induced cell death of CGN cultures established from nNOS−/− and wild type mice and infected with a negative control vector or the vector carrying nNOS coding sequences was assayed using the following procedure. Cells were plated into 96-well plates (5x105 cells/well) in defined medium and allowed to adhere and undergo the expected initial cell death phase for 18 hours before infection with the various adenoviral vectors. To determine the titer with least toxicity and adequate functionality, CGN cultures were infected with a range of titers (0 to 1000 pfu/cell serial dilutions) of a control vector (Ad5-Bgl II, which is an adenoviral empty vector carrying only a Bgl II site) and Ad5-nNOS vector (Channon et al., 1996) (an adenoviral vector carrying coding sequences of the nNOS gene under the control of the CMV promoter, courtesy of Dr. Keith Channon, Oxford University). The titer of 100 pfu per cell was chosen because this titer induced minimal toxicity, while it provided neuroprotection against alcohol. Live cell number of a replica well was determined. Cells in each group were transduced by exposure to 100 pfu of viral vector per cell. The control group received 100 pfu/cell of Ad5-Bgl II vector. The complementation group [nNOS(−/−) + Ad5-nNOS], and over-expression group [nNOS (+/+) + Ad5-nNOS] received 100 pfu/cell of Ad5-nNOS vector. The cultures were incubated at 37°C for 24 hours prior to alcohol exposure. The cultures were then exposed to 0 or 400 mg/dl ethanol for an additional 24 hours. Following the alcohol exposure, the number of viable granule cells in each well was determined. The cells were counted on a hemocytometer using exclusion of trypan blue as an indicator of cell viability. To calculate the percentage of cells killed by alcohol in each condition, the number of viable cells in each alcohol-exposed group was subtracted from the mean number of viable cells in the no-alcohol group, then divided by the mean number of viable cells in the no-alcohol group.

4.6. SKNSH cell culture, transfection, and reporter enzyme assays

The human neuroblastoma cell line SKNSH was grown in medium supplemented with MEM, 15% fetal bovine serum, and L-Glutamine. Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine plus reagent (Invitrogen Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. 2x10 5 cells were transfected with 2μg of reporter construct. To document transfection efficiency, we transfected SKNSH cells with an expression vector encoding green fluorescent protein and analyzed transfection efficiency under a fluorescent microscope by quantifying EGFP-positive and EGFP-negative cells. The SKNSH cells were transfected with high efficiency. Quantification revealed that 48% were transfected. nNOS promoter-reporter constructs composed of 854-bp of the nNOS gene promoter carrying two cAMP response elements fused to the coding region of the beta-galactosidase gene (wt nNOSp-β-Gal) and a mutated version of the same construct carrying mutations within both cAMP response elements (mut nNOSp-β-Gal) (generous gift of Dr. Ted Dawson, Johns Hopkins University) (Sasaki et al., 2000) were used in transfection experiments. 48 hours after the transfection, cells were harvested and lysed in reporter lysis buffer. Beta-galactosidase activity was measured using the Galacto-light chemiluminescent reporter assay (Tropix) in a Lumat LB9501 luminometer (Berthold). The protein concentration of each extract was determined using the BioRad protein assay dye reagent (BioRad). Beta-galactosidase activity measured for each promoter construct was normalized by protein concentration. Three independent experiments were carried out for each reporter construct activity.

4.7. RNA isolation, cDNA synthesis and real-time quantitative PCR assay

Total RNA was isolated from CGN cultures of control and treatment groups using the Trizol (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD) method, according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total RNA (2μg) was reverse transcribed using SuperscriptTMII (Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). After concentration determination on a UV spectrophotometer (Eppendorf Biophotometer), 250 ng of cDNA was used as the template for amplification of the nNOS message. The real-time quantitative PCR primers and probe for mouse nNOS were designed to cross an intron, using published sequences ((Ogura et al., 1993); GeneBank Access. # NM 008712). Sequences of the real time quantitative PCR primers and probe for nNOS are as follows; nNOS-5’ 5’-AAA CCT GCA AAG TC TAA ATC CA-3’; nNOS-3’ 5’-TGG TAC TGC AAC TCC TGA TTC CT-3’; nNOS-probe 5’-6FAM-CCA TCT TCG TGC GTC TCC ACA CCA-3BHQ-3’.

The iNOS and rRNA primers and probes were purchased from PE Applied Biosystems. The TaqMan PCR reaction was carried out as described previously (Karacay et al., 2001). A cloned ribosomal RNA fragment was used to generate a standard curve for relative quantitation.

4.8 Western blot analysis

5x104 CGN were plated onto 24-well plates and permitted to adhere overnight before addition of adenoviral vectors. The cells were washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) immediately prior to infection. The cells were induced with Ad5-nNOS and/or Ad5-Bgl II vectors at 100 pfu/cell concentration. Forty-eight hours after the infection, protein extract was isolated using a RIPA buffer (Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA). 25 μl of protein extract was then diluted with 5 μl of 6X SDS-PAGE loading buffer, heated for 5 min at 100°C, separated by SDS-PAGE, and transferred to nitrocellulose membrane (Novex, San Diego, CA). Following an overnight block in 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS-Tween-20 (0.05% v/v), the membrane was incubated with the anti-nNOS antibody (diluted 1:500, Santa Cruz Biotechnologies, Santa Cruz, CA). After washing, the membrane was incubated with an HRP-labeled anti-rabbit IgG antibody (diluted 1:5000, Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ) for 1 h. Following several washes, the blots were developed by chemiluminescence according to the manufacturer’s protocol (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescence Substrate, Pierce). After removal of nNOS antibody using Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (Pierce), the membrane was incubated with mouse anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody (ICN Biomedicals, Aurora, OH) followed by Peroxidase AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG, F(ab')2 Fragment Specific (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Following several washes, the blot was developed by chemiluminescence as described above.

4.9. Determination of Nitrite Concentration

Nitric oxide formation was evaluated in wild type CGN cultures by measuring accumulation of nitrite, which is a stable and non-volatile breakdown product of nitric oxide. Twenty-four hours after plating, cultures were treated with forskolin (0 or 10 μM concentration) for 24 hours. NO accumulation in the culture medium was then determined by the Griess reaction according to the manufacturer’s (Promega) protocol (Griess, 1879). Briefly, culture supernatants (50 μl) were mixed with 50 μl of sulfanilamide solution (1% sulfanilamide in 5% phosphoric acid). After 10 minutes incubation at room temperature, 50 μl of NED solution (0.1% N-1-napthylethylenediamine dihydrochloride in water) was added to each sample. After 10 min at room temperature, samples were measured at 520 nm wavelength. Nitrite concentrations were calculated against a nitrite standard (0.1M sodium nitrite in water) .

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Keith Channon of Oxford University for the adenoviral expression vector carrying nNOS cDNA and Dr. Ted Dawson of John’s Hopkins University for the nNOS promoter-beta-galactosidase reporter constructs.

Abbreviations

- CGN

Cerebellar Granule Neurons

- NO

Nitric Oxide

- nNOS

Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase

- cAMP

Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate

- CREB

cAMP Response Element Binding Protein

- CRE

cAMP Response Element

- NMDA

N-Methyl-D-Aspartate

- FAS

Fetal Alcohol Syndrome

- eGFP

Enhanced Green Fluorescent Protein

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

Footnotes

This research was supported by NIH grants NS02007, AA011577, and AA015747, the Children’s Miracle Network, and a Carver Collaborative Grant.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Nicholas J. Pantazis, Email: nicholas-pantazis@uiowa.edu.

Daniel J. Bonthius, Email: daniel-bonthius@uiowa.edu.

References

- Beauvais F, Michel L, Dubertret L. The nitric oxide donors, azide and hydroxylamine, inhibit the programmed cell death of cytokine-deprived human eosinophils. FEBS Letters. 1995;361:229–232. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(95)00188-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. Ethanol Promotes Apoptosis in Cerebellar Granule Cells by Inhibiting the Trophic Effect of NMDA. J Neurochem. 1997;68:578–586. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.68020578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boissel JP, Bros M, Schröck A, Gödtel-Armbrust U, Förstermann U. Cyclic AMP-Mediated Upregulation of the Expression of Neuronal NO Synthase in Human A673 Neuroepithelioma Cells Results in a Decrease in the Level of Bioactive NO Production: Analysis of the Signaling Mechanisms that Are Involved. Biochem. 2004;43:7197–7206. doi: 10.1021/bi0302191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, Karacay B, Dai D, Hutton A, Pantazis NJ. The NO-cGMP-PKG pathway plays an essential role in the acquisition of ethanol resistance by cerebellar granule neurons. Neurotoxicol Teratol. 2004;26:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ntt.2003.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, Karacay B, Dai D, Pantazis NJ. FGF-2, NGF and IGF-1, but not BDNF, utilize a nitric oxide pathway to signal neurotrophic and neuroprotective effects against alcohol toxicity in cerebellar granule cell cultures. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2003;140:15–28. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00549-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, McKim R, Koele L, Harb H, Hutton Kehrberg A, Karacay B, Pantazis NJ. Severe alcohol-induced neuronal deficits in the hippocampus and neocortex of neonatal mice genetically deficient for neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) J Comp Neurol. 2006;499:290–305. doi: 10.1002/cne.21095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, Tzouras G, Karacay B, Mahoney J, Hutton A, McKim R, Pantazis NJ. Deficiency of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) worsens alcohol-induced microencephaly and neuronal loss in developing mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2002;138:45–59. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(02)00458-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, West JR. Alcohol-induced neuronal loss in developing rats: increased brain damage with binge exposure. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res. 1990;14:107–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1990.tb00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonthius DJ, Woodhouse J, Bonthius NE, Taggard DA, Lothman EW. Reduced seizure threshold and hippocampal cell loss in rats exposed to alcohol during the brain growth spurt. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2001;25:70–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Channon KM, Blazing MB, Potts KE, Shetty GA, George SE. Adenoviral gene transfer of nitric oxide synthase: high level expression in human vascular cells. Cardiovascular Research. 1996;32:962–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiarini LB, Freitas ARO, Zanata SM, Brentani RR, Martins VR, Linden R. Cellular prion protein transduces neuroprotective signals. EMBO Journal. 2002;21:3317–3326. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chun SY, Eisenhauer KM, Kubo M, Hsueh AJ. Interleukin-1 beta suppresses apoptosis in rat ovarian follicles by increasing nitric oxide production. Endocrinology. 1995;136:31201–3127. doi: 10.1210/endo.136.7.7540548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung YH, Kim YS, Lee WB. Distribution of neuronal nitric oxide synthase-immunoreactive neurons in the cerebral cortex and hippocampus during postnatal development. J Mol Histol. 2004;35:765–770. doi: 10.1007/s10735-004-0667-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani E, Guidi S, Bartesaghi R, Contestabile A. Nitric oxide regulates cGMP-dependent cAMP-responsive element binding protein phosphorylation and Bcl-2 expression in cerebellar neurons: implication for a survival role of nitric oxide. J Neurochem. 2002a;82:1282–1289. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani E, Virgili M, Contestabile A. Akt pathway mediates a cGMP-dependent survival role of nitric oxide in cerebellar granule neurons. J Neurochem. 2002b;81:218–228. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dimmeler S, Haendeler J, Nehls M, Zeiher AM. Suppression of Apoptosis by Nitric Oxide via Inhibition of Interleukin-1beta -converting Enzyme (ICE)-like and Cysteine Protease Protein (CPP)-32-like Proteases. J Exp Med. 1997;185:601–608. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genaro AM, Hortelano S, Alvarez A, Martinez C, Bosca L. Splenic B lymphocyte programmed cell death is prevented by nitric oxide release through mechanisms involving sustained Bcl-2 levels. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:1884–1890. doi: 10.1172/JCI117869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Bonthius DJ, Wasserman EA, West JR. An animal model of central nervous system dysfunction associated with fetal alcohol exposure: Behavioral and neuroanatomical correlates. In: Wasserman EA, editor. Learning and Memory: Behavioral and Biological Processes. Englewood, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1992. pp. 183–208. [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett, Charles R, Horn, Kristin H, Zhou, Feng C. Alcohol Teratogenesis: Mechanisms of Damage and Strategies for Intervention. Exp BiolMed. 2005;230:394–406. doi: 10.1177/15353702-0323006-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodlett CR, Eilers AT. Alcohol-induced Purkinje cell loss with a single binge exposure in neonatal rats: A stereological study of temporal windows of vulnerability. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1997;21:738–744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griess P. Bemerkungen zu der abhandlung der H.H. Weselsky und Benedikt. Ueber einige azoverbindungen Chem Ber. 1879;12:426–428. [Google Scholar]

- Huang PL, Dawson TM, Bredt DS, Snyder SH, Fishman MC. Targeted disruption of the neuronal nitric oxide synthase gene. Cell. 1993;75:1273–1286. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90615-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutton Kehrberg AM, Pantazis NJ, McKim RA, Bonthius DJ. A nitric oxide signaling pathway protects the developing brain against alcohol-induced neuronal death. In: Preedy V, editor. Comprehensive Textbook of Alcohol Related Pathology. Vol. 2. Elsevier; London: 2005. pp. 873–887. [Google Scholar]

- Karacay B, O'Dorisio MS, Kasow K, Hollenback C, Krahe R. Expression and fine mapping of murine vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor 1. J Mol Neurosci. 2001;17:311–324. doi: 10.1385/JMN:17:3:311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lonze BE, Ginty DD. Function and regulation of CREB family transcription factors in the nervous system. Neuron. 2002;35:605–623. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00828-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo J, West JR, Pantazis NJ. Nerve growth factor and basic fibroblast growth factor protect rat cerebellar granule cells in culture against ethanol-induced cell death. Alcohol: Clin ExpRes. 1997;21:1108–1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannick JB, Asano K, Izumi K, Kieff E, Stamler JS. Nitric oxide produced by human B lymphocytes inhibits apoptosis and Epstein-Barr virus reactivation. Cell. 1994;79:1137–1146. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90005-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantamadiotis T, Lemberger T, Bleckmann SC, Kern H, Kretz O, Martin VA, Tronche F, Kellendonk C, Gau D, Kapfhammer J, Otto C, Schmid W, Schutz G. Disruption of CREB function in brain leads to neurodegeneration. Nat Genet. 2002;31:47–54. doi: 10.1038/ng882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayr B, Montminy M. Transcriptional regulation by the phosphorylation-dependent factor CREB. Nature Rev Mol Cell Biology. 2001;2:599–609. doi: 10.1038/35085068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlhany RE, Jr, West JR, Miranda RC. Glial-derived neurotrophic factor rescues calbindin-D28k-immunoreactive neurons in alcohol-treated cerebellar explant cultures. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:835–847. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlhany RE, Jr, West JR, Miranda RC. Glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) prevents ethanol-induced apoptosis and JUN kinase phosphorylation. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 2000;119:209–216. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(99)00171-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monti B, Marri L, Contestabile A. NMDA receptor-dependent CREB activation in survival of cerebellar granule cells during in vivo and in vitro development. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;16:1490–1498. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.02232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura T, Yokoyama T, Fujisawa H, Kurashima Y, Esumi H. Structural Diversity of Neuronal Nitric Oxide Synthase mRNA in the Nervous System. Biochem Biophys Res Comm. 1993;193:1014–1022. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis NJ, Dohrman DP, Goodlett CR, Cook RT, West JR. Vulnerability of cerebellar granule cells to alcohol-induced cell death diminishes with time in culture. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1014–1021. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1993.tb05657.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis NJ, Dohrman DP, Luo J, Thomas JD, Goodlett CR, West JR. NMDA prevents alcohol-induced neuronal cell death of cerebellar granule cells in culture. Alcohol: Clin Exp Res. 1995;19:846–853. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1995.tb00957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantazis NJ, West JR, Dai D. The nitric oxide-cGMP pathway plays an essential role in promoting survival of cerebellar granule cells in culture and protecting cells against ethanol neurotoxicity. J Neurochem. 1998;70:1826–1838. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.70051826.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio A, Ahn S, Davenport CM, Blendy JA, Ginty DD. Mediation by a CREB family transcription factor of NGF-dependent survival of sympathetic neurons. Science. 1999;286:2358–2361. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5448.2358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riccio RS Alvania, Lonze BE, Ramanan N, Kim T, Huang Y, Dawson TM, Snyder SH, Ginty DD. A nitric oxide signaling pathway controls CREB-mediated gene expression in neurons. Mol Cell. 2006;21:283–294. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santacana M, Uttenthal LO, Bentura ML, Fernandez AP, Serrano J, Martinez de Velasco J, Alonso D, Martinez-Murillo R, Rodrigo J. Expression of neuronal nitric oxide synthase during embryonic development of the rat cerebral cortex. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111:205–222. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00140-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki M, Gonzalez-Zulueta M, Huang H, Herring WJ, Ahn S, Ginty DD, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Dynamic regulation of neuronal NO synthase transcription by calcium influx through a CREB family transcription factor-dependent mechanism. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8617–8622. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.15.8617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber SS, Baudry M. Selective neuronal vulnerability in the hippocampus -- a role for gene expression? Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:446–451. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(95)94495-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shioda S, Ohtaki H, Nakamachi T, Dohi K, Watanabe J, Nakajo S, Arata S, Kitamura S, Okuda H, Takenoya F, Kitamura Y. Pleiotropic Functions of PACAP in the CNS: Neuroprotection and Neurodevelopment. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006;1070:550–560. doi: 10.1196/annals.1317.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokol RJ, Miller SI, Reed G. Alcohol abuse during pregnancy: an epidemiologic study. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1980;4:135–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1980.tb05628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K. Alteration of second messengers during acute cerebral ischemia—Adenylate cyclase, cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase, and cyclic AMP response element binding protein. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;65:173–207. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(01)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thippeswamy T, McKay JS, Morris R. Bax and caspases are inhibited by endogenous nitric oxide in dorsal root ganglion neurons in vitro. Eur J Neurosci. 2001;14:1229–1236. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-816x.2001.01752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SE, Kelly SJ, Mattson SN, Riley EP. Comparison of social abilities of children with fetal alcohol syndrome to those of children with similar IQ scores and normal controls. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:528–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, Sirimanne E, Williams C, Gluckman P, Dragunow M. The role of the cyclic AMP-responsive element binding protein (CREB) in hypoxic-ischemic brain damage and repair. Mol Brain Res. 1996;43:21–29. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(96)00144-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton M, Woodgate AM, Muravlev A, Xu R, During MJ, Dragunow M. CREB phosphorylation promotes nerve cell survival. J Neurochem. 1999;73:1836–1842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walton MR, Dragunow I. Is CREB a key to neuronal survival? Trends Neurosci. 2000;23:48–53. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(99)01500-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]