Abstract

Background: Overweight, weight cycling, and obesity are major health risks with psychological effects that should not be overlooked by mental health professionals.

Method: This article examines behavioral and other factors associated with weight, weight changes, and obesity in 3940 college-educated women, using data from responses to self-administered mailed questionnaires received from fall 1996 to winter 1997.

Results: The mean age of the women was 53.6 years, SD = 12.2. Body mass indexes, prevalence of obesity, and behavioral practices were more favorable than those of women in the general U.S. population. The mean body mass index of the sample was 23.3; median, 22.5; 6.5% were obese, 5% currently smoked, and 68% exercised regularly. Over the past 10 years, 31% maintained the same weight, 11% lost weight, 48% gained weight, and 10% gained and lost weight. Women who both gained and lost weight were more likely to report physician-diagnosed depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependencies compared to women in the other 3 categories; the multivariable odds ratios are 1.48 (95% CI = 1.07, 2.05) versus those who maintained their weight, 1.38 (95% CI = 1.06, 1.80) versus those who gained weight, and 1.53 (95% CI = 1.06, 2.21) versus those who lost weight. Those who both lost and gained weight were also more likely to report having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons; the respective multivariable odds ratios versus those who maintained their weight, gained weight, and lost weight are 2.01 (95% CI = 1.28, 3.16), 2.21 (95% CI = 1.52, 3.22), and 2.19 (95% CI = 1.23, 3.89).

Conclusion: These findings affirm the view that mental health care deserves attention in the treatment of patients with problems with weight changes and weight control.

Increasing body weight and obesity are among the top health risks for the American public—children, women, and men of all ages and ethnic groups. The age-adjusted prevalence of obesity was 30.5% in 1999–2000 compared with 22.9% in 1988–19941; in 1999–2002, the prevalence of overweight among children aged 6 through 19 years was 16%.2 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services report “Tracking Healthy People 2010” identified overweight and obesity as one of the 10 leading health indicators.2,3

In addition to the morbidity and mortality that may or may not be associated with obesity and overweight,3–6 there are psychological effects, which should not be ignored by mental health professionals. It has been asserted that treatment of overweight and obesity should address not only their effects per se, but also their effects on self-esteem in a hostile cultural climate.7 Depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem deserve attention in the battle against obesity8 and “weight cycling,” gaining and losing weight.9,10

On the basis of this literature,7–10 this article examines the association between behavioral and mental health conditions as well as other factors with weight control and obesity among a group of highly educated, middle to upper-middle class, predominantly white women. The data analyzed are responses to a self-administered mailed questionnaire that were provided by this sample of women, who ranged in age from 37 to 80 and over.

METHOD

Subjects

A 15-year follow-up study of the health of college alumnae was conducted in 1996; data collection began in the fall of 1996 and was completed in the winter of 1997. The women, first identified and surveyed in 1982, were alumnae of 10 colleges and universities, including all of the “Seven Sisters” colleges (Barnard, Bryn Mawr, Mount Holyoke, Radcliffe, Smith, Vassar, and Wellesley), Springfield College (Springfield, Mass.), University of Southern California, and University of Wisconsin.11 The main purpose of the original study and the follow-up was to determine the long-term health of women who had been athletes in college compared to their nonathletic classmates.12,13 For the follow-up, current addresses of women who participated in the baseline study were obtained from each of the 10 participating colleges and universities, and questionnaires were sent to these women. College alumni offices were asked to provide names of alumnae who had died between 1982 and 1996. Women who did not respond to the first questionnaire were sent a follow-up request. Alumni offices reported that 268 alumnae had died (121 athletes and 147 nonathletes) between 1982 and 1996. Four hundred eighty women (8.9%) could not be reached either because the college alumni offices had no follow-up addresses or because questionnaires were nondeliverable. Thus, 748 women (13.8%) did not participate due to death, no follow-up addresses from the colleges, or nondeliverable questionnaires. Of the 4650 living alumnae who received questionnaires and therefore were possible respondents, 3940 women provided completed questionnaires (12 women returned blank questionnaires). Three additional women responded after the study's closing date and are not included in the analyses. Thus, the response rate was 3940/4650 (84.7%). The Harvard School of Public Health Human Subjects Committee approved the study. No incentives were used.

Procedures

Women were sent a detailed mailed questionnaire, much of its contents derived from a well-validated and widely used instrument—the questionnaire used in the Harvard Nurses' Health Study.14 It included inquiry about the following: medical history and physician-diagnosed illnesses, medications taken, and family history of medical conditions; weight and height; occupation and living arrangements; current exercise or athletic activity; smoking and alcohol consumption; physical limitations; and rating of general health.

The questions relating to weight change were as follows: “Has your weight changed during the last 10 years? Yes/No. If yes, please specify: pounds gained and pounds lost.” From their responses, women were classified into 4 categories: category 1, response No, classified as “same weight,” 31% of the sample; category 2, response Yes and number of pounds lost reported, classified as “lost weight,” 11% of the sample; category 3, response Yes and number of pounds gained reported, classified as “gained weight,” 48% of the sample; and category 4, response Yes and both number of pounds gained and number of pounds lost reported, classified as “gained and lost weight,” 10% of the sample. Women were also classified as obese or nonobese according to body mass index (BMI; weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared), based on reports of current weight and height. Obesity was defined as a BMI of 30 or greater.15

Health rating was based on the question, “In general, would you say your health is: Excellent, Very Good, Good, Fair, Poor?” Health rating was dichotomized close to the median; 44% of respondents reported excellent health, coded 0, and 56% reported not excellent health, coded 1.

Statistical Methods

Statistical analytic methods included descriptive statistics, comparisons among groups by χ2 and analysis of variance, and multivariable logistic regression to determine the association between weight changes and predictor variables. Variables eligible for inclusion in the logistic regression models were those that showed significant differences by weight change categories based on univariate analysis (Table 1) and included the following binary variables (Yes/No): having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons, taking vitamins, taking prescription medications, current smoking, regular exercise, sexual intercourse 1 or more times per week, living with spouse, and observing a low-calorie diet and the following physician-diagnosed conditions: alcoholism, depression, respiratory conditions, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, fractures, chronic back problems, benign breast disease, and degenerative arthritis.

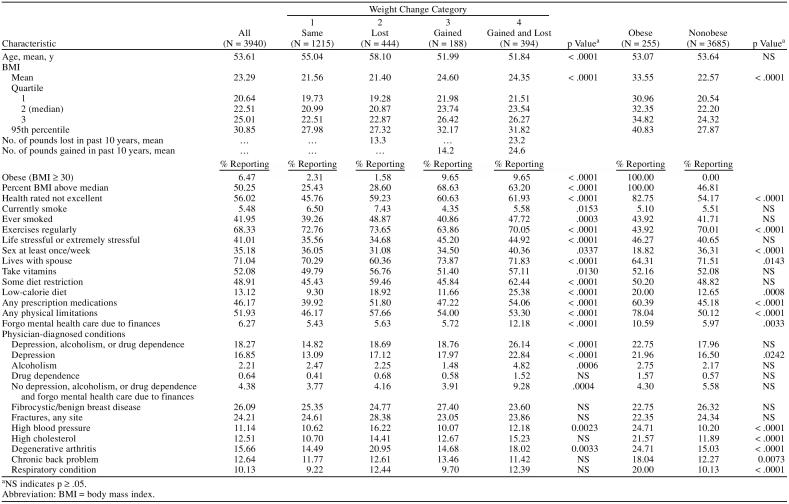

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of All Participants and Participants Classified by Weight Change Category and by Obese/Nonobese Status

(Physician-diagnosed conditions reported by fewer than 10% of the women, including diabetes, eye problems [cataract extraction, macular degeneration, glaucoma], cancers, cardiovascular disease, a group of miscellaneous physician-diagnosed conditions—diverticulitis, Crohn's disease, systemic lupus erythematosus claudication of legs, kidney stones, cholecystectomy, and sexually transmitted diseases—as well as a category, other illnesses or surgery since 1980, that included conditions ranging from ectopic pregnancy to cranial aneurysm, are not shown.)

Multivariable analyses using logistic regression were carried out to determine the predictive factors that might account for weight maintenance, weight loss, weight fluctuations (gained and lost), and weight gain. Analyses tested for the significance of interactions among variables. Nonsignificant interactions were not included in the models. A reduced multivariable model included variables that were significant in the multivariable logistic regression analyses. Goodness-of-fit was assessed by the Hosmer-Lemeshow test. Analyses were done using SAS for PC.16

RESULTS

Descriptive data for women of all ages (N = 3940) and by the 4 weight categories are shown in Table 1. The median age at time of reporting was 51.0 years (mean age 53.6, standard deviation 12.2). The median BMI was 22.5 (mean 23.3, standard deviation 3.9). According to national standards, only a fourth of the women would be considered overweight (BMI 25 or over), and only 6.5%, obese (BMI 30 or over). The women, largely white, highly educated, and middle to upper-middle class, tended to adhere to good behavioral practices. Sixty-eight percent exercised regularly, 5% currently smoked, 49% reported some dietary restrictions, and 13% reported a low-calorie diet. Forty-six percent reported taking prescription medications; 52%, vitamins.

Fifty-six percent rated their health as not excellent on a 5-point scale—excellent, very good, good, fair, or poor. About half (52%) reported at least 1 physical limitation. A history of the following physician-diagnosed illnesses or conditions (excluding miscellaneous and other illness or surgery) was reported by 10% or more of the participants: 24% any type of fracture, 18% all types of arthritis (16% degenerative), 17% depression, 13% chronic back problem, 13% high cholesterol, 11% high blood pressure, and 10% respiratory illness. Notably, a history of diabetes, often associated with obesity, was infrequent; diabetes (type 1 or type 2) was reported by 1.3% of the entire sample.

Descriptive data by weight change category—1, no change (same weight); 2, lost weight; 3, gained weight; and 4, gained and lost weight—and by obese/nonobese status are also in Table 1. Women in categories 3 and 4 were younger and had higher BMIs than other women. The mean BMIs differed by weight category: 21.6, 21.4, 24.6, and 24.4 for categories 1 to 4, respectively; BMIs in categories 1 and 2 differed significantly from those in 3 and 4 (Table 1). Over the last 10 years, the mean number of pounds gained among those who both gained and lost was 24.6, and among those who gained, 14.2. The mean number lost in the gained and lost group was 23.2, and in those who lost, 13.3. Notably, among women who both gained and lost, the mean number of pounds gained was about the same as the mean number of pounds lost and considerably higher than amounts gained by women who only lost and women who only gained.

Women who reported the same weight over the last 10 years (category 1) were more likely to rate their health favorably and less likely to report physical limitations. Women in category 2 (lost), in addition to being older, were more likely to report at least 1 physical limitation.

It is noteworthy, however, that there were minor differences among the weight change categories with respect to common illnesses and chronic diseases such as high cholesterol, high blood pressure, back problems, arthritis, benign breast disease (Table 1), cancers, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (data not shown).

The women who both gained and lost weight (category 4) differed significantly from the other 3 groups with respect to mental health conditions; they were more likely to report physician-diagnosed depression, alcoholism, and drug dependence. Although a small proportion of participants reported having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons, a significantly higher proportion of this group so reported—12.2%, compared with 5.4%, 5.6%, and 5.7%, respectively, for the same, lost, and gained groups. Among women without psychiatric diagnoses of depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependence (but possibly other mental health problems, about which no inquiry was made), the percentages were, respectively, 9.3%, 3.8%, 4.2%, and 3.9% for the gained-and-lost, same, lost, and gained groups (Table 1).

Descriptive data for obese (6.5% of the sample) and nonobese women indicate that obese women not only were more likely to report their health as not excellent, but also were more likely to have medical conditions—high blood pressure, high cholesterol, chronic back pain, degenerative arthritis, respiratory conditions, and at least 1 physical limitation (Table 1).

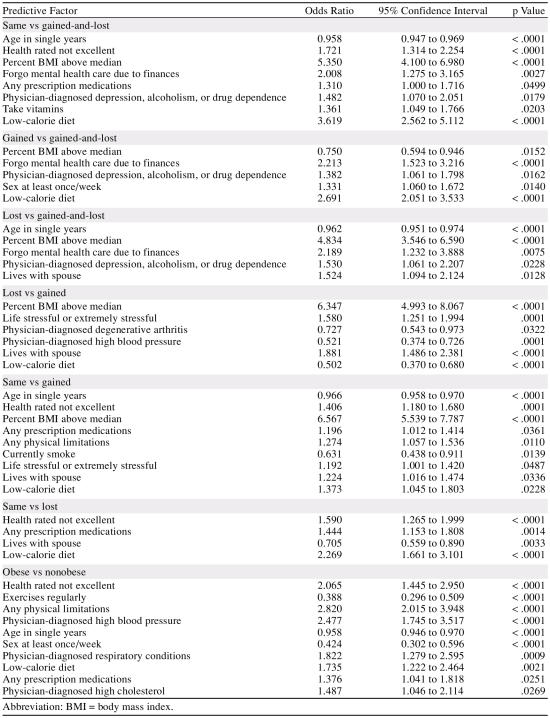

Table 2 shows results of multivariable logistic regression, adjusted for possible predictive and confounding factors. Three main comparisons are of those who both gained and lost compared with the following: same weight, gained weight, and lost weight. A number of variables significant by univariate analysis were no longer significant in the multivariable models (Table 2). The women who both gained and lost weight were more likely to report physician-diagnosed depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependencies than women in the comparison groups; the odds ratios, 95% confidence intervals, and p values were 1.48 (1.07, 2.05), p = .018 versus same weight; 1.38 (1.06, 1.80), p = .016 versus gained weight; and 1.53 (1.06, 2.21), p = .023 versus lost weight. Having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons was significantly associated with weight change category 4 (both gaining and losing weight). The odds ratios, 95% CIs, and p values were 2.01 (1.28, 3.16), p = .003 versus same weight; 2.21 (1.52, 3.22), p < .0001 versus gained weight; and 2.19 (1.23, 3.89), p = .008 versus lost weight.

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for the Associations of Weight Change Categories and Predictive Factors

Results of logistic regression analyses for 3 additional comparisons of lost versus gained, same versus gained, and gained versus lost and for the comparison of obese and nonobese women are also in Table 2.

DISCUSSION

Among college-educated women, the subset who both gained and lost weight differed, with respect to mental health, from those who maintained their weight, lost weight, and gained weight. The differences are primarily in their reporting of physician-diagnosed depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependencies and their reporting of having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons.

This article is based on self-reports of largely white, educated middle to upper-middle class women, whose recall and responses tend to be accurate and reliable with respect to their medical histories, behavioral practices, and weight changes. They reported adhering to recommended health-promoting practices, and their obesity rate is lower than rates of the general population of women; the median BMI was 22.5; only 6.5% were obese (BMI of 30 or over), and one fourth were overweight (BMI of 25 or over). Their self-reports appear to have face validity.

No inquiry was made about mental health problems other than physician-diagnosed depression, alcoholism, and substance abuse, and no details on mental health–seeking behavior or mental health–related medications are available. However, even among the subset of women (N = 3220) who did not report depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependence, but who may have had other self-perceived or diagnosed mental health problems, women who both gained and lost weight were significantly more likely to report having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons than women in the same weight, lost weight, or gained weight categories; the percentages are, respectively: 9.3%, 3.8%, 4.2%, and 3.9% (Table 1). For women who both gained and lost weight, the mean number of pounds gained was 24.6, and the mean number of pounds lost was 23.2—a net difference of about 1 pound.

A possible limitation of this study is that women were asked about weight changes “during the last 10 years”; no information was sought about the frequency of weight changes or weight fluctuations during this period. The National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity in 1994 provides a comprehensive review entitled “Weight Cycling” and an updated review in 2000; “Dieting and the Development of Eating Disorders in Overweight and Obese Adults.”9,10 There is, however, no clear conclusion about health and psychological effects of weight cycling. Weight fluctuation was strongly associated with negative psychological attributes in both normal weight and obese individuals.17 Among obese women, weight cycling was related to perceived physical health.18 Among obese Italian women, weight cycling was associated with psychological distress.19 Among Finnish men and women from the general population, weight cycling was associated with poor self-perceived health, and “severe” weight cyclers were likely to use some medication, compared to “mild” cyclers, nonobese nondieters, and obese nondieters.20 On the other hand, a prospective study of an obese clinical population found no negative psychological effects.21 However, weight cycling may be consistent with lack of control, self-esteem, self-efficacy, and behavioral issues.21 Although in the present study weight change was determined “during the last 10 years” and no other measure of weight cycling was available, the findings of the study, as well as those from other studies, may have important implications for both researchers and providers of mental health services.

As noted, the gained and lost group was more likely to be on a low-calorie diet, reflecting the recognition of a “weight problem,” but the apparent inability to control their weight. This finding is in accord with Field et al.,22 who reported that severe weight cyclers, in comparison with those who maintained weight over a 5-year period, preferred to change their diet rather than exercise. The prevalence of obesity, reported in 6.5% of the sample, was far lower than the national averages; however, comparisons of obese respondents versus the 94% who were nonobese confirmed the well-known observation that obesity is a health problem—the obese tended to have more high blood pressure, high cholesterol, diabetes, and respiratory problems than the nonobese. More of them also reported at least 1 physical limitation, rated their health as not excellent, and reported not engaging in regular exercise. Weight gain and obesity were found to be inversely associated with frequency of sexual intercourse (Table 2). Assessment of self-esteem was not included in this study, but the results on sexual intercourse may be a proxy for self-esteem or how women feel about gaining weight, being overweight, and being obese. The face validity of the results on obese/nonobese women suggests that, despite the possible limitations of this study, the results on the 4 weight changes groups are reliable and valid.

Obesity and weight cycling may be associated with binge eating and psychological problems, although the data do not provide consistent results.9,10,18–20,22–27 (This study had no information on binge eating.)

These data are from self-reports of predominantly white, middle to upper-middle class women well enough and able to complete a self-administered questionnaire. Further, the prevalence of obesity, 6.5%, is far lower than national obesity prevalence figures. For these reasons, the results may not be generalizable to women of diverse backgrounds. The study was cross-sectional; from the associations observed, causation cannot be determined. This raises the question, Which comes first, psychological problems—depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependence—or weight problems? Further studies are suggested to understand the association between weight control and mental health in women from a broad spectrum of socioeconomic and racial/ethnic groups. The findings of this study, however, contribute to observations on the complex relations between weight cycling, i.e., weight fluctuations, and psychological effects, self-esteem, and health perception.

CONCLUSION

Among well-educated predominantly white women, who have better health promoting and weight profiles than the general U.S. population, the subset who both gained and lost weight, over a 10-year period, reported more physician-diagnosed depression, alcoholism, and/or drug dependence; were more likely to perceive having to forgo mental health care for financial reasons; and had poorer self-rating of health compared to women reporting no weight change, losing weight, and gaining weight over the same time period. These findings contribute to findings on the psychological effects of weight, weight cycling, and obesity. Further research on more diverse populations is needed. Nevertheless, weight control and weight cycling should not be ignored by mental health professionals, and treatment should address not only weight gain and weight cycling per se, but also their effects on health perception and self-esteem.

Footnotes

The Harvard School of Public Health and the Advanced Medical Research Foundation, Boston, Mass., funded preparation of the questionnaire, mailing of questionnaires, and data entry.

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES CITED

- Flegal KM, Carroll MD, and Ogden CL. et al. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2000. JAMA. 2002 288:1723–1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedley AA, Ogden CL, and Johnson CL. et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999–2002. JAMA. 2004 291:2847–2850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Dept Health Human Services. Tracking Healthy People 2010. Washington, DC: US Govt Printing Office. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Graubard BI, and Williamson DF. et al. Excess deaths associated with underweight, overweight, and obesity. JAMA. 2005 293:1861–1867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gregg EW, Cheng YJ, and Cadwell BL. et al. Secular trends in cardiovascular disease risk factors according to body mass index in US adults. JAMA. 2005 293:1868–1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mark DH.. Deaths attributable to obesity. JAMA. 2005;293:1918–1919. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.15.1918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devlin MJ, Yanovski SZ, Wilson GT.. Obesity: what mental health professionals need to know. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:851–853. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Is obesity a mental health issue? Harv Ment Health Lett. 2004;21:1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Weight cycling. JAMA. 1994;272:1196–1202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Task Force on the Prevention and Treatment of Obesity. Dieting and the development of eating disorders in overweight and obese adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2581–2589. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.17.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch RE, Wyshak G, and Albright NL. et al. Lower prevalence of breast cancer and cancers of the reproductive system among former college athletes compared to non-athletes. Br J Cancer. 1985 52:885–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyshak G, Frisch RE.. Breast cancer among former college athletes compared to non-athletes: a 15-year follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:726–730. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.1999.0987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyshak G.. Women's college physical activity and self-reports of physician-diagnosed depression and of current symptoms of psychiatric distress. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:363–370. doi: 10.1089/152460901750269689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colditz GA, Manson JE, Hankinson SE.. The Nurses' Health Study: a 20-year contribution to the understanding of health among women. J Womens Health. 1997;6:49–62. doi: 10.1089/jwh.1997.6.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Fryar CD, and Carroll MD. et al. Mean Body Weight, Height and Body Mass Index, United States 1960–2002: Advance Data From Vital and Health Statistics; No. 347. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics. 2004 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Statistical Analysis System. Cary, NC: SAS Institute. 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Foreyt JP, Brunner RL, and Goodrick GK. et al. Psychological correlates of weight fluctuation. Int J Eat Disord. 1995 17:263–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venditti EM, Wing RR, and Jakicic JM. et al. Weight cycling, psychological health, and binge eating in obese women. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996 64:400–405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesini G, Cuzzolaro M, and Mannucci E. et al. QUOVADIS Study Group. Weight cycling in treatment-seeking obese persons: data from the QUOVADIS study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 28:1456–1462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahti-Koski M, Mannisto S, and Pietinen P. et al. Prevalence of weight cycling and its relation to health indicators in Finland. Obes Res. 2005 13:333–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MM, King TK.. Eating self-efficacy and weight cycling: a prospective clinical study. Eat Behav. 2000;1:47–52. doi: 10.1016/s1471-0153(00)00009-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Field AE, Manson JE, and Taylor CB. et al. Association of weight change, weight control practices, and weight cycling among women in the Nurses' Health Study II. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 28:1134–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elfhag K, Rossner S.. Who succeeds in maintaining weight loss? a conceptual review of factors associated with weight loss maintenance and weight regain. Obes Rev. 2005;6:67–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2005.00170.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehnel RH, Wadden TA.. Binge eating disorder, weight cycling, and psychopathology. Int J Eat Disord. 1994;15:321–329. doi: 10.1002/eat.2260150403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brownell KD, Rodin J.. Medical, metabolic, and psychological effects of weight cycling. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:1325–1330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simkin-Silverman LR, Wing RR, and Plantinga P. et al. Lifetime weight cycling and psychological health in normal-weight and overweight women. Int J Eat Disord. 1998 24:175–183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teixeira PJ, Going SB, and Sardinha LB. et al. A review of psychosocial pre-treatment predictors of weight control. Obes Rev. 2005 6:43–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]