Introduction

The Maudsley Hospital officially opened in January 1923 with the stated aim of finding effective treatments for neuroses, mild forms of psychosis and dependency disorders. Significantly, Edward Mapother, the first medical superintendent, did not lay a claim to address major mental illness or chronic disorders. These objectives stood in contrast to the more ambitious agenda drafted in 1907 by Henry Maudsley, a psychiatrist, and Frederick Mott, a neuropathologist.1 While Mapother, Maudsley and Mott may have disagreed about the tactics of advancing mental science, they were united in their condemnation of the existing asylum system. The all-embracing Lunacy Act of 1890 had so restricted the design and operation of the county asylums that increasing numbers of reformist doctors sought to circumvent its prescriptions for the treatment of the mentally ill. Although the Maudsley began to treat Londoners suffering from mental illness in 1923, it had an earlier existence first as a War Office clearing hospital for soldiers diagnosed with shell shock,2 and from August 1919 to October 1920 when funded by the Ministry of Pensions to treat ex-servicemen suffering from neurasthenia. Both Mott, as director of the Central Pathological Laboratory and the various teaching courses, and Mapother had executive roles during these earlier incarnations. These important clinical experiences informed the aims and management plan that they drafted for the hospital once it had returned to the London County Council's (LCC) control.

On the surface, the Maudsley could not have been further from the traditional asylum. No attempt was made to hide the hospital in the countryside—it was located in a busy London suburb close to a railway station and on a tram route. The red-brick buildings with their Portland stone dressings executed “in a free treatment of English Renaissance” resembled a district general hospital or a town hall rather than a prison or asylum.3 With beds for only 144 patients, a postgraduate medical school and a dedicated outpatient department, it was a far cry from the barrack-like structures constructed for the county asylum system. Formal links were rapidly established with the adjacent King's College Hospital: Mapother lectured at its medical school, saw patients there and later was given access to a 35-bed ward.

Throughout the inter-war period the relationship between the Central Pathological Laboratory and the Maudsley Hospital remained problematic. The laboratory had been set up by the LCC to serve the medical needs of its 34,000 asylum beds. When transferred to the Maudsley site in January 1916, it retained its independent status but Mott willingly worked in tandem with Mapother on the study and treatment of shell shock. When Mott retired in March 1923, Frederick Golla, a consultant neurologist at St George's Hospital, was appointed as his successor.4 Golla had conducted research under Mott's supervision at the Maudsley towards the end of the war and in 1921 had given the prestigious Croonian Lectures.5 A man of personal wealth with an established reputation, Golla took charge of a department with a secure source of income. Although he and Mapother began on good terms, when differences of opinion drove them apart no institutional structure existed to encourage reconciliation. Golla had the academic status and financial security to select his own research targets, while Mapother had no formal claim on his laboratory time.

With its postgraduate medical school and clinical training posts, Mapother sought to establish an international reputation for the Maudsley in research and teaching. This paper explores how the strategic goals of the hospital's founders, Maudsley and Mott, were modified by clinical reality, legal constraints and the aims of the major grant awarding bodies.

Strategic Objectives of the Founders

The strategic goal set for the Maudsley Hospital was defined in the first instance by the bequest of Henry Maudsley.6 His offer of £30,000, made in December 1907, came with three conditions. Under the first, the hospital was to concentrate on “the early treatment of cases of acute mental disorder, with the view as far as possible, to prevent the necessity of sending them to the county asylums”.7 Maudsley believed cases of psychosis could be “cured” if caught early and subjected to “individual treatment, mental and medical” in an institution freed from stigma.8

In setting this target, Maudsley was influenced by discussions with Mott, who in 1895 had become director of the LCC's pathological laboratory at Claybury Asylum. Although he had “leanings towards physiology, normal and morbid, and neurology” at the time of his appointment, Mott reportedly “knew nothing about mental disorders”.9 His confirmation that general paralysis of the insane (GPI) was a manifestation of syphilis (associated with the presence of the spirochaete and expressed in the form of delusions and hallucinations) not only established his scientific reputation but led Mott to look for physical causes of mental disorders such as shell shock and dementia praecox.10 To arrest what were considered irreversible pathological processes, Mott proposed “some earnest attempt … to establish a means of intercepting for hospital treatment such cases of incipient and acute insanity as are not yet certifiable”.11 Only by the study of mental illness in its “early and yet curable stage” did Mott believe that new light could be thrown “on the essential causes and contributory factors”.12 In 1903, he advocated the opening of acute hospitals or “receiving houses”, akin to workhouse observation wards, which could offer short-term treatment thereby preventing admission to an asylum. In 1907, following a visit to Emil Kraepelin's clinic at Munich,13 Mott conceived a more ambitious scheme for a hospital with facilities for postgraduate training in psychiatry and neurology.14 Nevertheless, Kraepelin was not convinced and wrote, “an Englishman came to see me about opening a new mental hospital in London. It will come to nothing”.15 In his memoirs he made no reference to Mott's visit,16 though he was later said to have observed that “nothing” had come out of the UK “in psychiatry except through Mott”.17

With a relatively brief career in the asylum system ending as medical superintendent of the Manchester Royal Lunatic Asylum, Maudsley earned a considerable fortune as a psychiatrist in private practice. However, he harboured academic ambitions and was elected to the chair of medical jurisprudence at University College London, and edited the Journal of Mental Science from 1863 to 1878.18 Between them, Mott, the scientist, and Maudsley, the West End clinician, set the parameters for the new institution. Indeed, it was Mott who presented the scheme for a “hospital for the care and treatment of acute recoverable cases of mental disease” to the Asylums Special Sub-Committee in July 1907 and conducted subsequent negotiations with the LCC, while Maudsley remained the anonymous donor whose identity would be revealed only if the offer of £30,000 were accepted.19

In March 1908, when the LCC assented to the scheme, it was on the understanding that the hospital would offer “treatment, the direct object of which would be the cure and discharge of the patient”.20 It was also stipulated that the 100-bed hospital should be not more than four miles from Charing Cross so that it was accessible to both patients and students. Mott had found Claybury at Woodford Green, Essex, too remote from centres of population or public transport for any effective communication with other researchers and students.21 In addition, his application to have the laboratory recognized as an institution of higher education had been turned down because it fell outside the University of London's geographical limits.22

Implementing the Design

Estimated at £60,000, the LCC agreed to contribute half the capital expenditure.23 At £400 per bed (excluding purchase of the site), the Maudsley was an expensive enterprise, the comparative cost for a 2,000-bed asylum being £260.24 However, the Financial Committee of the LCC judged that the expenditure represented a reasonable risk because the “outpatient department would undoubtedly enable many patients to be kept out of the asylums” and that “great gain would accrue from the acquisition of knowledge in regard to the causes of insanity and its prevention”.25

The execution of the Maudsley project was hindered by practical and legal difficulties. Not until April 1911 was a site acquired that fell within the geographical boundary set by its benefactor. Two years earlier, the LCC's mental hospitals engineer, William C Clifford Smith, FRIBA, had, at the suggestion of Maudsley, undertaken a fact-finding visit to Kraepelin's clinic at Munich to gather “hints as to the design, staffing and administration” of the proposed institution. In 1912, Clifford Smith drafted detailed plans, which were approved by the Board of Control.26 Although he had designed other mental institutions (Manor Mental Hospital, Horton, and the Ewell Colony for Epileptics),27 both Maudsley and Mott had an input in the planning of the buildings. Construction was authorized in October 1913 and completed two years later, by which time building and site costs had risen to £69,750. Six wards (two for assessment and four for treatment) housed 144 beds rather than the 108 originally planned.28 Although small-scale, at £484 per bed, the Maudsley was scarcely a cheap alternative to an asylum.

In its overall design, the Maudsley bore a resemblance to the psychiatric clinic opened in 1904 at Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität in Munich. The three-storey building facing Denmark Hill housed the pathology laboratory, library, on-call bedrooms, dispensary and administrative offices. Before the construction of a purpose-built structure in 1933, the outpatient department was also located in the building with a side entrance for patients. Two three-storey structures, linked by bridges, housed six wards, each with 24 beds. Patients were segregated by gender, initially into separate blocks but soon after the opening by storey: the two wards on the first storey for men and the two below for women. The upper floors, allocated to those with mild disorders, were kept unlocked, and patients encouraged to exercise in the adjacent gardens. The two ground-floor wards were for reception and patients who required closer supervision; they were each “well supplied with ‘continuous baths’ for the treatment of the acute phases of mental illness and to combat insomnia”.29

In terms of bureaucratic control, Henry Maudsley along with other reformist doctors believed that the state had gone too far in standardizing procedures for the containment of patients with psychiatric disorders. In 1909, he outlined a blueprint for a “mental hospital” that would grant more freedom to doctors and patients alike:

A complaint often bitterly made by persons who have been discharged recovered from asylums is of … the degrading humiliation of being ordered about … in daily routine like so many sheep, without the least regard for personal feeling. Such a system of routine is no doubt more or less unavoidable in a large asylum crowded with patients in all stages of disease.30

To avoid such routine, Maudsley proposed a “small hospital filled with a constant succession of patients”, affording opportunities for individual attention and stimulating debate between physicians and students. This, he believed, would “sharpen observation, suggest inquiries, keep fresh the interest, prevent routine of thought, feeling and treatment”.31

Whilst the founders of the Maudsley Hospital could not be described as libertarian, they did believe that the power which the state had granted them on the basis of holding professional qualifications was so limited by the legislature as to render it almost worthless. In terms of research, training and treatment, the Lunacy Act of 1890 had reduced many psychiatrists to little more than custodians of the bizarre or unruly.

Legislation and Administrative Control

Although the Maudsley Hospital remained broadly subject to the 1890 Act and later to the Mental Health Act of 1930, together with regulations imposed by the Board of Control, it had been granted administrative freedoms denied to most UK mental institutions.32 The London County Council, which funded the hospital through its Asylums Committee,33 had sought special powers from Parliament in 1915 to allow it to defray the cost of treating voluntary patients, a privilege at the time granted only to licensed houses and registered hospitals.34 Under the LCC (Parks &c) Act, the Maudsley was permitted to

… receive and lodge as a boarder and maintain and treat … any person suffering from incipient insanity or mental infirmity who is desirous of voluntarily submitting himself to treatment … A voluntary boarder … shall be at liberty to leave the said hospital on giving 24 hours' notice of his intention to do so.35

Because the 1890 Act was comprehensive and so closely argued, asylum treatment was increasingly conceived as a last resort, rather than an opportunity for therapeutic experiment.36 Furthermore, no local authority could pay for the treatment of mental illness unless the patient had been certified. Hence, the statute imposed strict limits on the type of disorder that could be treated in an asylum, enforced by financial penalties for non-compliance or obstruction. In 1919, when the Maudsley was operated as a treatment centre for the Ministry of Pensions, Mapother as medical superintendent was concerned that a high proportion of admissions were both psychotic and violent.37 To protect these ex-service patients from themselves and others, he kept many confined to their wards. Because the hospital was designed, in both administrative and physical terms, for “severe neurasthenics”, Mapother complained that the “legal authority for the necessary restraint on the liberty of patients” was not in place.38 Mapother had made a clear break with the asylum system: “every effort is being made to have as many patients in an open ward as possible with a minimum of restraint”, and on locked wards “the patients are given greater liberty than in any public mental hospital, e.g. where it is at all possible they are allowed out freely in charge of their relatives, and taken for motor drives, and to public entertainments”.39

It is perhaps significant that both Mott at Claybury and Mapother at the Horton Estate (designated for 10,000 patients and the largest cluster of mental hospitals in the world)40 had direct experience of the scale and remoteness of the modern asylum. In addition, several members of Mapother's family had psychotic illnesses. His mother was recorded as suffering from “insanity”,41 while as a medical student he had committed his sister, Mary, to an asylum, and she was later to die as a patient in the Bethlem.42 Mapother had a personal motivation to improve the care and treatment of the mentally ill.

Maudsley: Clinical Operation

Although Mapother advocated the “treatment of mental disorders without certification and with the least possible restriction upon liberty”,43 he publicly set more modest goals than had been proposed by Maudsley. Interviewed by the New Statesman in February 1923, Mapother identified the following psychiatric disorders as suitable for treatment:

Neuroses (hysteria of various forms, neurasthenia, anxiety and obsessional states), and certain varieties of psychoses, e.g. mild phases of the manic-depressive type, psychoses associated with exhaustion, with pregnancy and the puerperal period, with post-infective states, with syphilitic brain disease of the interstitial types, with alcoholisms and other drug habits, with endocrine disturbances, and generally cases exhibiting mental symptoms associated with all forms of definite bodily disease.44

To exclude “altogether unsatisfactory” patients, those who might require physical restraint or sedation against their will, the Maudsley did not offer an emergency service.45

The death of Henry Maudsley on 23 January 1918 provided Mapother and Mott with an opportunity to modify the benefactor's blueprint. Mott's retirement from the directorship of the Pathological Laboratory had been delayed until 23 October 1922 (and later postponed to March 1923) to allow him to continue his research and supervise the “courses of clinical instruction in psychological medicine” held at the Maudsley.46 The experience of treating servicemen convinced both of them that:

(1) The presence in the hospital of any patients compulsorily detained would greatly limit the number and kinds of those entering at their own free will. (2) That … the running of the hospital on a wholly voluntary basis would be found perfectly compatible with the presence of all for whom it was desirable to provide treatment there and who would serve as the requisite material for teaching and research.47

Although little was reported of the Maudsley's patient population, the hospital was described as a centre for “the treatment of the neuroses of a peace-time economy”.48 However, preliminary analysis of discharge notes for 1924 and 1936–38 suggests that the situation was more complex than this or Mapother's public pronouncement implied. A random sample drawn from 1924 showed that 24 per cent of admissions were diagnosed with schizophrenia or manic-depressive psychosis (Table 1). Anxiety states and conversion disorders (then termed hysteria) were comparatively rare and the most common admission was for depression or melancholia (29 per cent).

Table 1.

Maudsley Hospital: random sample of patients by diagnosis in 1924

| Schizophrenia | Depression | Manic-depression | Other psychoses | Anxiety disorder | Obsessional disorder | Other neuroses | Organic disorders | Unknown | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inpatients | ||||||||||

| Male | 10 | 10 | 2 | – | 3 | 2 | 3 | 6 | – | 36 |

| Female | 6 | 19 | 6 | 11 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 8 | 2 | 64 |

| Total | 16 | 29 | 8 | 11 | 8 | 4 | 8 | 14 | 2 | 100 |

| Outpatients | ||||||||||

| Male | 6 | 3 | – | 3 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 3 | – | 26 |

| Female | 4 | 12 | 1 | 1 | 9 | – | 18 | 1 | 3 | 49 |

| Total | 10 | 15 | 1 | 4 | 13 | 2 | 23 | 4 | 3 | 75 |

Source: BRHA, Maudsley Hospital patient discharge notes for 1924.

It appears that Mapother's mission statement of 1923 was a carefully considered view of those disorders that he thought were amenable to study and treatment. The notable omission from his list of clinical targets was schizophrenia. It is interesting to speculate why Mapother then admitted such cases. In reality, no psychiatric research institution that sought to establish an international reputation could afford to ignore such an important and devastating disorder. Mapother was fortunate in one respect; he could discriminate between referrals and exclude those with what appeared to be a poor prognosis. Certainly by 1926, very few patients were admitted from asylums (Table 2).

Table 2.

Maudsley Hospital: source of patients

| Year | Private doctor | General hospital | Mental hospital | Social organizations | Re-admissions or recommended by ex-patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1926 | 566 (54) | 169 (15) | 37 (3) | 65 (6) | 225 (22) |

| 1930 | 915 (62) | 204 (14) | 34 (2) | 51 (3) | 277 (19) |

Figures in parentheses are percentages.

Source: BRHA, C/12/4 Mapother Box 13.

In 1931, when mounting a major appeal to found an institute of psychiatry, Mapother restated the clinical goal of the Maudsley as the

… treatment of neurosis and of mental illness of any degree of severity, provided this is deemed curable … It is not merely treatment for an initial period, but is intended to continue to recovery if this is possible within a short time—hardly ever exceeding one year and averaging three months.49

This change of emphasis allowed Mapother to include schizophrenia and manic-depressive psychosis within the hospital's targets but exclude severe or chronic cases.

Due to the closure of the Maudsley in September 1939, most of its inpatient records for the late 1930s have been lost. However, the clinical picture revealed by the surviving discharge summaries for 1937–38 suggests that the population had not changed greatly over the inter-war period, depression and schizophrenia being among the prominent diagnoses (Table 3).

Table 3.

Maudsley Hospital adult patients by diagnosis for 1937–38

| Schizophrenia | Depression | Manic-depression | Other psychoses | Anxiety disorder | Obsessional disorder | Other neuroses | Organic disorders | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| In patients | |||||||||

| Male | 2 | 5 | 1 | 2 | 10 | ||||

| Female | 4 | 8 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 19 | |||

| Total | 6 (21) | 13 (45) | 3 (10) | 5 (17) | 2 (7) | 29 (100) | |||

| Outpatients | |||||||||

| Male | 6 | 3 | – | – | 7 | – | 8 | 8 | 32 |

| Female | 6 | 15 | 1 | 1 | 20 | 1 | 15 | 5 | 64 |

| Total | 12 (13) | 18 (19) | 1 (1) | 1 (1) | 27(28) | 1 (1) | 23 (24) | 13 (14) | 96 (100) |

Figures in parentheses are percentages.

Source: BRHA, Maudsley Hospital patient discharge notes for 1937–38.

As regards clinical management, Mapother sought to preserve the liberal regime introduced under the auspices of the Ministry of Pensions. In the winter, a weekly event, a concert, dance or whist drive, was organized, while in the summer a fortnightly picnic in the countryside took place.50 Great emphasis was placed on fresh air to prevent the spread of infectious diseases both in themselves and as possible triggers for mental illness. The ground-floor wards opened on to verandas, and patients were encouraged to use the hospital gardens, which were shielded from the station and road by a screen of trees.

In their annual report for 1930, the Board of Control commissioners recorded that there was “no employment of mechanical means of restraint”.51 However, the hospital had been criticized in November 1928 for not having a separate building for “restless and at times noisy patients”, who remained on the wards where they disrupted therapeutic activities.52 As a result, in 1931 at a cost of £12,590, a single-storey villa with 18 beds was constructed in the gardens to house patients who were willing to be treated but who were difficult to manage.53 Once the villa was opened, the wards in the main building could be left unlocked.

By definition, voluntary patients could not be restrained by mechanical means, so it was necessary to consider other ways of limiting the harm that they could do to themselves and others. The villa was designed with spacious rooms that opened on to an enclosed garden, while the partitions were of armour-plated glass and rubber floors were installed.54 Because Mapother considered padded cells “a real and undesirable anachronism”, in 1937 the hospital acquired “gitter” beds fitted with removable padded sides and a net that prevented the patient from climbing out.55 Their use led to a formal complaint by the Board of Control that they breached the hospital's legal guidelines.56 The five continuous baths in the villa were regarded as acceptable because the hole in the cover for the patient's head was sufficiently large for the patient to climb out unaided. Legal opinion, sought on the use of netted beds, was divided. Two lawyers argued that restraint was incompatible with voluntary status, while C F Penton advised that the net could be used as a short-term measure during an acute phase of illness because it was part of a package of treatment to which the patient had earlier agreed.57

In an attempt to resolve the issue, Drs Aubrey Lewis and Flora Calder were asked to report on the use of such beds in the six Metropolitan observation wards.58 These self-contained units established in general hospitals (Fulham, St Pancras, St Clements, St Alfeges, St Francis and St John's) were designed to provide an opportunity to assess psychiatric disorders without the stigma and certification associated with the asylum system. In 1936, 6,233 patients were admitted to the London observation wards of whom 3,117 were transferred to mental hospitals (only 10 per cent of these went as voluntary patients) and 1,054 discharged to the care of relatives. Agitated patients were occasionally restrained in beds covered with netting. Lewis and Calder concluded that use of these beds should be discontinued because of the “distress” they caused to patients and because they might encourage managers to reduce the number of nurses employed and thereby result in restless patients “not receiving from nurses the personal attention they need”.59 Although the Board of Control granted the Maudsley permission to use netted beds for patients who were “not only restless but confused” and for those awaiting transfer to an asylum, by April 1939 they were no longer in use at the hospital.60

Londoners were admitted “irrespective of their means”,61 the cost being borne by the LCC, though it was expected that the better off should make a financial contribution. Although the Council sought to avoid the “suggestion that the Maudsley Hospital is reserved chiefly for paying patients”, in June 1922 staff accommodation was converted into accommodation for thirteen private patients.62 Those living outside Greater London had to pay fees, which for a week of inpatient treatment was £5.00. A preliminary analysis of the home addresses of those treated in 1924 and 1937–38 suggests that the charge discouraged referrals from beyond the metropolis.

Running costs for the first year of the hospital's operation were estimated at £37,500,63 a large sum because of the high levels of medical staffing required. In 1923, in addition to Mapother, who was part-time, there were four full-time doctors (A A W Petrie, the deputy superintendent and three assistant medical officers), supported by six medically-qualified clinical assistants, who worked on a voluntary basis to gain experience. A matron, assistant matron, six sisters and nineteen staff nurses with at least three years' general hospital training were supported by twenty-three probationers and twelve male nurses.64

A cardinal rule established by Mapother was that the hospital should have no waiting list so that incipient and mild cases could be treated immediately.65 By 1932, the demand for beds had become so pressing that it was difficult to sustain this principle, and Mapother negotiated the lease of a 35-bed ward (“Pantia Ralli”) from King's College Hospital. Known as the “Maudsley Annex”, this was a temporary measure while construction proceeded on the outpatient building, the children's department and the private patients' block.66 This expansion programme saw the number of beds rise to 260 by 1939,67 though the greatest growth came from the treatment of outpatients and children.

Outpatients

An outpatients department, conceived as the “principal source of admittance”, had opened at the Maudsley in December 1922.68 It operated on two afternoons a week, which, in response to rapidly increasing demand, was increased to four.69 The idea of treating psychiatric disorders without admission was still novel but not unprecedented. Asylum doctors, who wished to treat psychiatric patients before they became so ill that they required certification, had concluded that this was one way to circumvent the 1890 Act. Dr Henry Rayner, lecturer on mental diseases and later medical superintendent at Hanwell Asylum, had opened an outpatient clinic for psychological disorders at St Thomas' Hospital in 1890, while four London teaching hospitals (Guy's, Charing Cross, St Mary's and UCL) set up similar departments before 1914.70 Dr L S Forbes Winslow set up a charitable outpatient clinic in Euston Road, London, to treat mental illness among the poor.71 Hubert Bond, a commissioner at the Board of Control, told an audience at the Middlesex Hospital in 1915 that he could “see no reason why they [outpatient clinics] should not be established in connection with every hospital in the country”.72 In 1919, the Bethlem Royal Hospital, a high-profile asylum in Lambeth, opened an outpatient clinic.73 In the same year, the Ministry of Pensions set up a UK network of outpatient psychotherapy, euphemistically described as “Special Medical Clinics”, to treat veterans suffering from shell shock. By October 1920, twenty-nine clinics were in operation, though retrenchment saw most of them close soon afterwards.74

In its first ten months of operation, 736 cases were seen as outpatients, including 31 children. Of these 50 were discharged as fully recovered, 250 were admitted as inpatients.75 So rapid was the growth of this service that a full-time medical officer (C C Davis) and two part-time ones (D C Carroll and Merrill Middlemore) were recruited to work exclusively with outpatients. In 1932 almost 2,000 new patients were registered annually, although most lived within a two-mile radius of the hospital.76 Because the Maudsley had a London-wide remit, the LCC agreed to fund the opening of satellite departments in three of their hospitals north of the Thames (Mile End, St Mary's Highgate and St Charles' in Ladbroke Grove).77

Children's Department

When the Maudsley was first conceived, no provision was made for the treatment of children, and the rapid growth in this patient population was unforeseen. It arose in part because of changing attitudes to infant development and the rise of the child guidance movement. This targeted what were described as the “nervous, difficult or delinquent” as opposed to those who had learning difficulties.78 In 1928, a child guidance clinic was set up under the directorship of Dr William Moodie, the deputy medical superintendent. The terms used to describe child outpatients were a mixture of formal psychiatric diagnoses, symptoms and behavioural problems (Table 4). The department was promoted as an example of the value of teamwork: “psychiatrists to diagnose and to prescribe, psychologists for mental testing, social workers to deal with the environmental side and voluntary workers to observe the activities of the children in the play room”.79 With a grant from the Commonwealth Fund, Maudsley staff also ran a child guidance clinic in North London. Most children were treated as outpatients, but if they required admission they were accommodated in adult wards alongside those with mild mental disorders. The need for a dedicated children's ward was soon recognized, though it was not until the mid-1930s that funds were forthcoming from the LCC. A children's block with its own outpatients was completed just before the outbreak of war, though the inpatient unit did not open until January 1947.

Table 4.

Children treated as outpatients in 1937–38

| Problem identified/diagnosis | Boys | Girls |

|---|---|---|

| Anxiety disorder | 10 | 7 |

| Backwardness | 10 | 4 |

| Behavioural problems | 21 | 20 |

| Chorea | 1 | 1 |

| Enuresis | 5 | 6 |

| Epilepsy | 1 | 1 |

| General abnormality | – | 1 |

| Hysteria | 1 | 1 |

| Nervous moods | – | 1 |

| Night terrors | – | 1 |

| Post-encephalitic problems | – | 1 |

| Reading difficulties | 3 | 1 |

| Stammering/shaking | 1 | – |

| Cyclic vomiting | 1 | – |

| Excitability | 1 | – |

| Sexual abnormality | 1 | 2 |

| Tics | 1 | 1 |

| Dementia | 1 | – |

| Incontinent | 2 | – |

| Habit spasm | 1 | – |

| Schizophrenia | – | 1 |

| Total | 61 | 49 |

Source: BRHA, Maudsley Hospital patient discharge notes for 1937–38.

Research

The second condition laid down by Henry Maudsley was that the hospital “promote exact scientific research into the causes and pathology of insanity”.80 By 1920, a consensus had emerged amongst some physicians that an urgent need existed for facilities for the early treatment of cases combined with facilities for research.81 The immediate post-war period was a time of great optimism in medical circles that major mental illness (schizophrenia and manic-depressive psychosis) could be understood and cured. “Today”, Adolf Meyer announced in 1921, “we feel that modern psychiatry has found itself” and that significant progress could be made if the study and treatment of psychosis were integrated within medical schools and their hospitals.82 In adopting what he termed “psychobiology”, Meyer sought to avoid the pitfalls of dualism, the intellectual split between body and mind, in any research agenda.

In July 1923, Henry Cotton, medical director of the Trenton State Hospital, New Jersey, was invited to speak to the Medico-Psychological Association on his hypothesis that schizophrenia and other forms of psychosis were the product of focal sepsis.83 Pus infection, whether in the colon, tonsil, teeth or elsewhere in the body, he believed, caused microscopic lesions in the cerebral cortex, which disappeared when the sepsis was treated. Mott also spoke at the meeting and offered support for this unitary explanation of major mental illness, adding that “Dr Cotton's work showed very emphatically the importance of a study of the bowel as a source of chronic infection”.84 As a result, Mott argued that great care should be taken to prevent “bowel disease—ulceration of the bowel—from typhoid, paratyphoid, and dysentery” from spreading in asylums. He also advocated investigation of the endocrine system, which served as “the foundation of the nervous condition of the body”.85 This strategy had the welcome side-effect of drawing psychiatry within the ambit of general medicine and, if successful, would have raised the status of its practitioners. “The value of this steady scientific research into the physical disorders underlying mental illness”, Mott concluded, “is unquestioned”.86 The focal sepsis hypothesis was pursued with enthusiasm by some medical superintendents, notably Thomas Graves at Rubery Hill and Hollymoor mental hospitals, where he encouraged patients to undergo surgical procedures to remove teeth, sinuses and tonsils, while other anti-infective initiatives included vaccinations, continuous colonic lavage and ultra-violet light treatment.87

However, Mapother was not swept along by the tide of false optimism, and remained cautious about the chances of finding a cure for psychosis. In 1925 he entered “a plea for scepticism” on the grounds that no medical scientist had any “definite information on the prevention of mental disorder”.88 Possibly his asylum experience at Epsom and wartime work at Southport and the Maudsley had taught him that whatever the treatment setting and whatever the background of the patient, these disorders possessed an intractable quality.

Although the Central Pathological Laboratory had moved into the Maudsley medical school, it remained small-scale with a biochemist, histologist and bacteriologist, supplemented by asylum medical officers seconded for three-month periods of training.89 Given these constraints and the source of its funding, the laboratory focused on the routine investigations of the LCC's asylums rather than the research agenda of the hospital clinicians despite the fact that every medical officer employed at the Maudsley was required to undertake a scientifically-based investigation.90 Mapother and Golla increasingly disagreed on the general strategy for research into the causes of mental illness, and relations between them deteriorated to the extent that by the early 1930s the hospital and the laboratory operated almost as separate institutions.91

Acutely aware of the need to create an institute of psychiatry that would be more responsive to the questions asked by the hospital's clinicians, in March 1931 Mapother launched an appeal for funding. Having concluded before the Maudsley opened that major mental illness was not readily addressed by existing treatments (sedatives, physical restraints, occupational therapy or continuous baths) and aware that there was nothing in the therapeutic pipeline, Mapother and his clinical team were presented with a serious dilemma. How could they persuade prestigious funders, such as the Rockefeller Foundation or the Medical Research Council (MRC), to support their enterprise when clinical advance was so elusive? One solution was to tackle less severe forms of mental illness and in particular to treat children with behavioural problems. However, these modest targets failed to interest high-profile funders. Furthermore, the Maudsley had no track record of scientific research into clinical questions other than the neurological inquiries pursued by Mott and Golla. Although Mapother was able to secure a small number of short-term fellowships from the Rockefeller, these did little to enhance the Maudsley's status as a centre for international research. In the early 1930s he approached both the MRC and the Rockefeller to fund “a few stable posts with salaries adequate for permanency” but found neither willing to make such a commitment.92 The MRC had been “very critical of previous standards of work in psychiatry in England” and had “included in this criticism the Maudsley”.93 Alan Gregg, director of medical sciences at the Rockefeller Foundation, expressed similar concerns. Not until a group of German émigrés arrived at the Maudsley in 1934–35, was the latter willing to commit increasing sums to its research budgets. These included Professor W Mayer-Gross from Heidelberg, Dr Erich Guttmann from Breslau, Dr Adolph Beck from Marburg and Professor Alfred Meyer from Bonn.94 Orientated towards the Kraepelin model of psychiatry, they found a receptive audience at the Maudsley because, as Lewis later wrote, of its crucial combination of “early treatment, research and postgraduate teaching”.95 Three years after their arrival, the Rockefeller awarded the Maudsley a substantial grant for research (£9,000 over three years) and in 1938 discussed an annual award of £4,000.96

However, it was not simply the arrival of respected German psychiatrists that persuaded Gregg to support the Maudsley. In the mid-1930s Mapother modified his overall strategy in several key areas, agreeing to take a greater role in undergraduate teaching (see below) and to broaden the range of research targets. The power of major medical charities to influence research agendas was apparent even in the inter-war period. By 1938, Daniel P O'Brien, the Rockefeller's assistant medical director based in Paris, advised Gregg that the Maudsley had become “good enough to plunge fairly heavily in the way of support”.97 By this time, Professor Edward Mellanby, a physiologist and secretary of the MRC, had also changed his mind and indicated a willingness to fund long-term research at the hospital.

Teaching and Training

The third goal set for the Maudsley by the Rockefeller Foundation was that it “serve as an educational institution, in which medical students might obtain good clinical instruction”.98 Indeed, Mott hoped that the setting up of such a school would encourage London University to validate a qualification in psychological medicine akin to the Diploma of Public Health, which would help to raise psychiatry to the level of other medical specialties.99 From 1920 onwards, the LCC funded courses in psychiatry for junior doctors employed in the asylum service.100 Under the direction of Mott, the school was designed to prepare them for the Diploma in Psychological Medicine (DPM) and was a successor to the lectures given to army doctors at the Maudsley in the treatment of shell shock. These courses became the core teaching of the Maudsley Hospital Medical School when it was established in 1924.101 Medical officers employed by the LCC were sent as clinical assistants in groups of four for three months' training. By 1931 the Maudsley had become the principal teaching institution for the DPM and routinely taught “medical officers with study leave from the army, air force and other government services whether stationed in England or abroad”.102 In 1938, sixty-five postgraduates, of whom twenty were from overseas, were being taught at the hospital.

Although recognizing the Maudsley's role as a postgraduate medical school, Mapother resisted Gregg's suggestion that he assume responsibility for the teaching of psychiatry to undergraduates at King's College Hospital. Gregg believed that the low status of psychiatry and difficulties in recruiting talented doctors needed to be addressed at an earlier stage in their training. Better quality teaching and research in the leading medical schools would create “an interest in the medical student body” and thereby grant psychiatric hospitals a better chance to complete for “the best brains in the medical schools”.103 The opening of a Maudsley ward in King's itself provided the opportunity to teach medical students. In March 1938, O'Brien reported to Gregg that “Mapother has given quite a bit of thought to this and has turned completely to your view”, adding, “[he] has more flexibility than I considered possible during my early contact with him”.104 Whether Mapother's change of heart was genuine or driven by the need to raise substantial grant income from the Rockefeller Foundation was not revealed.

By 1932, Mapother was able to claim with some justice that the Maudsley was “the main post-graduate school of mental medicine in England”, though the failure to establish an institute of psychiatry, “such as those in Munich, in Utrecht and in New York” was identified as a major failing.105 In his 1923 interview, Mapother had been careful not to state an ambition to make the Maudsley the UK's pre-eminent psychiatric institution. Apart from offering a hostage to fortune, a number of psychiatric institutions in the UK had programmes of reform and research, including the Royal Edinburgh Asylum under Thomas Clouston, while the West Riding Mental Hospital at Wakefield provided the first professor of psychiatry at Leeds Medical School, Joseph Shaw Bolton. Cardiff Mental Hospital also had a tradition of conducting research from 1909 onwards and had opened an outpatient department in 1919. By January 1938, O'Brien, from his objective stance in Paris, was willing to admit that Mapother's claim to “first place as a centre for research and teaching in psychiatry” was tenable “insofar as Europe is concerned”, though he added this would not have been the case five years earlier.106 The arrival of the German émigrés and the funding that followed had been crucial in moving the hospital up the academic league table.

Management Structure

Although only part-time, Mapother was, in effect, the chief executive of the Maudsley Hospital responsible for every activity, except the Pathological Laboratory, which was directed by Golla. Initially, because of the small number of staff (reputedly they could all fit around a single table for lunch), there was little in the way of formal managerial structure. As the hospital grew in size and specialist functions were added, so the need for division along functional lines arose. The first psychologist (part-time) was appointed in 1930, though expansion was delayed until the Second World War. The need to measure the aptitude of soldiers diagnosed with psychological disorders drew psychologists into research. John C Raven, used Progressive Matrices, a pre-war test designed to measure innate intelligence, to identify servicemen with deep-seated neuroses, while in 1942 H J Eysenck, a German émigré, was appointed to conduct research at Mill Hill where he was supported by Rockefeller funding.107 By 1946 there were four psychologists: M B Shapiro, H Himmelweit, J Stephen, and Eysenck, who four years later was appointed to a readership.108 The children's and outpatient departments demanded their own staff, the latter including a small number of psychotherapists. By 1935, the number of psychiatric social workers had risen to six.

By the late 1930s, Aubrey Lewis had emerged as Mapother's successor to the chair of psychiatry. However, his intellectual rigour and uncompromising Socratic approach did not mark him out for personnel roles. As a result, when the Maudsley closed on 2 September 1939 and its clinical staff divided between two suburban hospitals for the treatment of civilian psychiatric casualties, Lewis was not appointed to the medical superintendent posts. Louis Minski, junior to Lewis by a year, took charge at Sutton, and W S Maclay, who had joined the Maudsley in February 1934, ran Mill Hill. Eliot Slater became clinical director at Sutton with William Sargant as his deputy, while Lewis became clinical director at Mill Hill.

As the Maudsley Hospital had grown and Mapother's health deteriorated (he suffered from asthma and fibrosis of the lungs), it was apparent that a new structure organized along functional lines was needed. In December 1938, a plan was under discussion to split authority between Mapother, who would retain control over hospital administration, private patients and undergraduate teaching, and a clinical director who would be responsible for postgraduate teaching and research.109 However, the closure of the Maudsley in September 1939 prevented the new structure from being implemented until October 1945. Then the management of the Maudsley was reorganized to serve “both as a university psychiatric centre and as an executive hospital responsible for a psychiatric service covering the whole of London”.110 Aubrey Lewis, recently appointed professor of psychiatry, became clinical director, while A B Stokes served as the medical superintendent.

Conclusions

The Maudsley was criticized by contemporaries and subsequently on the grounds that it admitted only patients with mild disorders or those with a good prognosis, ignoring the “non-volitional cases, who form a not inconsiderable class”.111 A preliminary analysis of the patient population suggests that though those with chronic disorders were excluded, cases of schizophrenia and manic-depressive psychosis were regularly admitted. Mapother was almost as much a prisoner of the 1890 Act as the asylum doctor. Because the hospital could admit only voluntary patients, the range of treatments and management techniques available to the medical staff was reduced. The moment a patient took objection to a medicine or programme of activity, they were free to leave. Mapother's reluctance to sanction cardiazol fits,112 lobotomy and insulin coma therapy may, in part, have been driven by the knowledge that patients would vote with their feet. These were intrusive, unpleasant and dangerous interventions with no objective scientific evidence to support their use. Sargant believed that Mapother “feared to risk the lives of voluntary [patients], especially with our fierce local Coroner waiting to pounce on us at the slightest provocation”.113 Initially, Mapother barred insulin coma therapy but later permitted its use under supervision of a Swiss expert in December 1938.114

The hospital expanded rapidly during the inter-war period, the main brake on its growth being financial. The number of inpatients almost doubled. However, the greatest expansion was unforeseen and was a function of diversification into outpatients and increased specialization into child guidance. Despite the bequest and charitable aims of Henry Maudsley, the hospital was not an altruistic venture driven by patient needs. It served the purpose of ambitious doctors who found themselves thwarted by the asylum system. Concerned to unlock the secrets of mental illness, Mapother and Mott, and later Lewis, needed a steady supply of co-operative patients with whom they could explore their latest hypotheses and conduct clinical trials of novel medicines and procedures. Mapother and Lewis knew that they were in for the long haul.

Some juniors, such as William Sargant and Eliot Slater, interpreted the scepticism and restraint of Mapother and Lewis as “inertia, over-cautiousness and therapeutic nihilism”.115 Their strategy was unashamedly medical and interventionist:

Organic conditions, such as vitamin deficiencies and general paralysis, if allowed to persist for any length of time, produce some scarring from which there can never be complete recovery. The same is true of schizophrenia.116

In the belief that “bold experimenters” attracted “success”, they proposed a “rational therapy” based on the latest physical interventions (including insulin coma, electro-convulsive therapy, prefrontal leucotomy and intravenous barbiturates). These, they argued, had to be applied quickly and sometimes radically to halt irreversible change and thereby prevent chronicity.117 Whilst fashionable treatments, such as drug-induced fits and psychic surgery, may have attracted external funding, Mapother and Lewis were reluctant to take such bold steps in the absence of studies designed to test clinical efficacy. Their guarded approach was justified by the potential harm done to patients and validated in the post-1945 period by scientific investigations.

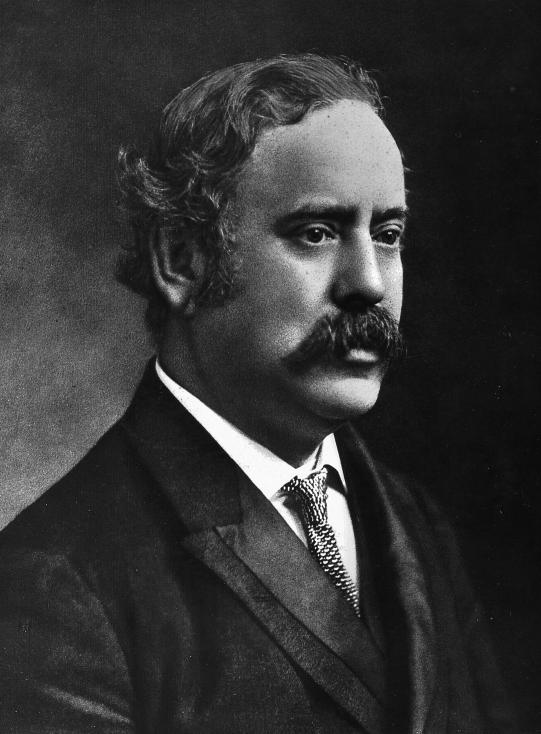

Figure 1.

Frederick Mott (1853–1926), director of the London County Council's Central Pathological Laboratory (Institute of Psychiatry, London).

Figure 2.

The main entrance to the Maudsley Hospital, photographed in May 1935. The buildings were designed by the LCC's mental hospitals engineer, William C Clifford Smith, FRIBA (London Metropolitan Archives).

Figure 3.

The private patients' block at the Maudsley photographed in July 1939. It was designed by the LCC architects E P Wheeler and G Weald. It had an enclosed roof garden for patients who were thought likely to harm themselves (London Metropolitan Archives).

Figure 4.

The playroom for the children's outpatients department, photographed in 1939 (London Metropolitan Archives).

Acknowledgments

The research for this paper was supported by a grant from the Wellcome Trust. The authors are grateful to Professor Robin Murray for his comments on earlier drafts.

Footnotes

1 Patricia Allderidge, ‘The foundation of the Maudsley Hospital’, in German E Berrios and Hugh Freeman (eds), 150 years of British psychiatry 1841–1991, London, Gaskell, 1991, pp. 79–88, p. 83.

2 F W Mott, ‘Preface’, Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 1918, 7: v–vi, on p. v; anon., ‘The opening of the Maudsley Hospital’, Lancet, 1923, i: 194.

3 Anon., ‘The London County Council Maudsley Hospital’, The Architect, 1923, 109: 426.

4 J M Bird, ‘The father of psychophysiology—Professor F L Golla and the Burden Neurological Institute’, in Hugh Freeman and German E Berrios (eds), 150 years of British psychiatry. Vol. II, The aftermath, London, Athlone, 1996, pp. 500–16, p. 501.

5 F L Golla, ‘The objective study of neurosis’, Lancet, 1921, ii: 115–22, 215–21, 265–70, 373–9.

6 London Metropolitan Archives (hereafter LMA), Published minutes of London County Council, 18 Feb. 1908, p. 282.

7 Ibid., item 2, p. 282.

8 Ibid.

9 The National Archives (hereafter NA), FD 1/244, Letter from Edwin Goodall to Sir Walter Fletcher, 3 Oct. 1932.

10 Alfred Meyer, ‘Frederick Mott, founder of the Maudsley Laboratories’, Br. J. Psychiatry, 1973, 122: 497–516, pp. 507, 508; E A Sharpey-Schafer and Rachel Davies, ‘Sir Frederick Walker Mott’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004 (hereafter ODNB), vol. 39, pp. 498–9; Rhodri Hayward, ‘Making psychiatry English: the Maudsley and the Munich model’, in Volker Roelcke and Paul Weindling (eds), Inspiration, co-operation, migration: British–American–German relations in psychiatry, 1870–1945, University of Rochester Press, in press.

11 F W Mott, ‘Preface’, Arch. Neurol., 1903, 2: vii–xiv, on p. xi.

12 F W Mott, ‘Preface’, Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 1914, 6: v–ix, on p. ix.

13 Hayward, op. cit., note 10 above.

14 F W Mott, ‘Preface’, Arch. Neurol., 1907, 3: iii–vii, on p. vi.

15 David Goldberg, ‘Obituary, Michael Shepherd (1923–1995)’, Psychol. Med., 1995, 25: 1109–11, on p. 1111.

16 Emil Kraepelin, Memoirs, Berlin, Springer, 1987. Speaking of his Munich clinic, Kraepelin wrote: “once, a couple of gentlemen from England came to see us; psychiatric clinics like ours did not exist in England at that time. They looked at everything in detail, but as I had heard from an English colleague, they later claimed that they had not seen anything special or different from other clinics. Otherwise, Englishmen rarely came to visit; amongst the more well-known colleagues, Clouston came to visit”, p. 136.

17 NA, FD 1/244, Letter from Edwin Goodall, medical superintendent of Cardiff Mental Hospital, to Sir Walter Fletcher, 3 Oct. 1932. According to Goodall, Kraepelin claimed German ancestry for Mott to account for his productive research.

18 T H Turner, ‘Henry Maudsley’, ODNB, vol. 37, pp. 409–10.

19 Allderidge, op. cit., note 1 above, pp. 83–4.

20 LMA, Published minutes of the London County Council, 10 Mar. 1908, item 34, p. 797.

21 F W Mott, ‘Preface’, Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 1909, 4: iii–v, p. iii.

22 Mott, op. cit., note 11 above, p. xiii.

23 LMA, Published minutes of the London County Council, 25 Mar. 1908, item 33, p. 796.

24 Ibid., p. 797.

25 Ibid.

26 LMA, Report of the Asylums and Mental Deficiency Committee, 27 June 1922.

27 Royal Institute of British Architects Library, Kalendars and Nomination Papers Fellows 916–1920, Reel 14, William Charles Clifford Smith, p. 3; Antonia Brodie et al. (compilers), Directory of British Architects, 1834–1914, Vol. 2: L–Z, London, Continuum, 2001, p. 657.

28 Bethlem Royal Hospital Archives (hereafter BRHA), C/12/4, E Mapother, ‘Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry’, March 1931, p. 2.

29 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 2.

30 Henry Maudsley, ‘A mental hospital—its aims and uses’, Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 1909, 4: 1–12, p. 11.

31 Ibid., p. 9.

32 NA, MH 51/640, Report of the Royal Commission on Lunacy and Mental Disorder, London, HMSO, 1926, p. 18.

33 William Eric Jackson, Achievement: a short history of the London County Council, London, Longmans, 1965, pp. 174, 293; E C R Hadfield and James E MacColl, Pilot guide to political London, London, Pilot Press, 1945, pp. 120–1.

34 Sir Gwilym Gibbon and Reginald W Bell, History of the London County Council 1889–1939, London, Macmillan, 1939, pp. 347, 359.

35 NA, MH 51/640, Report of the Royal Commission on Lunacy and Mental Disorder, London, HMSO, 1926, Appendix XIII, p. 945.

36 Kathleen Jones, ‘Law and mental health: sticks or carrots?’ in Berrios and Freeman (eds), op. cit., note 1 above, pp. 81–102, pp. 95–6; Kathleen Jones, A history of the mental health services, London, Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1972, p. 226.

37 NA PIN 15/55, Letter from E Mapother to Col. A W Sheen, 29 Dec. 1919.

38 NA PIN 15/55, Letter from E Mapother to Col. A W Sheen, 17 Dec. 1919.

39 Ibid.

40 Henry R Rollin, ‘Psychiatry in Britain one hundred years ago’, Br. J. Psychiatry, 2003, 183: 292–98; Rhodri Hayward, ‘Edward Mapother’, ODNB, vol. 36, pp. 587–8.

41 BRHA, CB184, Case Book Females (1908), Mary Mapother, 25 Jan. 1908, p. 10.

42 BRHA, CB252, Case Book Females (1947), p. 44.

43 NA PIN 15/55, Letter from E Mapother to Col. A W Sheen, 17 Dec. 1919.

44 E Mapother, ‘The study of insanity’, New Statesman, 24 Feb. 1923.

45 LMA, Report of the Asylums and Mental Deficiency Committee, 27 June 1922.

46 LMA, Minute of the Asylums Committee, 11 Oct. 1921.

47 BRHA, C/12/4, E Mapother, ‘Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry’, March 1931, p. 3.

48 Jones, A history, op. cit., note 36 above, p. 235.

49 BRHA, C/12/4, E Mapother, ‘Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry’, March 1931, p. 1.

50 NA, MH 95/32, B T Hodgson and A Rotherham, Report, 16 Dec. 1924, p.2.

51 NA, MH 95/32, R Cunyngham Brown, Report, 27 June 1930, p. 1.

52 NA, MH 95/32, R Cunyngham Brown, Report, 28 Nov. 1928, p. 1.

53 NA, MH 95/32, S J Fraser Macleod and A Rotherham, Report, 2 Oct. 1931, p. 1.

54 NA, MH 95/32, I G H Wilson and N C Croft Cohen, Report, 18 May 1937, p. 1.

55 NA, MH 95/32, Letter from R H Curtis, 6 Oct. 1937, p. 2.

56 Ibid., p. 1.

57 NA, MH 95/32, Memo, C F Penton, 18 Oct. 1937.

58 NA, MH 95/32, A Lewis and F H M Calder, ‘A general report on the observation wards administered by the LCC’, Dec. 1938.

59 Ibid., pp. 15, 16.

60 NA, MH 95/32, Minute, 17 April 1939.

61 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 3.

62 LMA, Report of the Asylums and Mental Deficiency Committee, 27 June 1922.

63 Ibid.

64 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 3.

65 BRHA, C/12/4, E Mapother, ‘Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry’, March 1931, p. 9.

66 NA, MH 95/32, Memorandum from E Mapother to the sub-committee appointed to consider possible developments arising out of the Mental Treatment Act of 1930, p. 1.

67 Gibbon and Bell, op. cit., note 34 above, p. 360.

68 LMA, Report of the Asylums and Mental Deficiency Committee, 27 June 1922; ibid., 25 July 1922.

69 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 2.

70 Richard Mayou, ‘The history of general hospital psychiatry’, Br. J. Psychiatry, 1989, 155: 764–76, on p. 769.

71 Louise Westwood, ‘A quiet revolution in Brighton: Dr Helen Boyle's pioneering approach to mental health care, 1899–1939’, Soc. Hist. Med., 2001, 14: 439–57, on p. 449.

72 Hubert Bond, ‘The position of psychiatry and the role of general hospitals in its improvement’, J. Ment. Sci., 1915, 61: 1–17, on p. 16.

73 J G Porter Phillips, ‘The early treatment of mental disorder: a critical survey of out-patient clinics’, Lancet, 1923, ii: 871–4.

74 Edgar Jones and Simon Wessely, From shell shock to PTSD: military psychiatry from 1900 to the Gulf War, Hove, Psychology Press, 2005, p. 154.

75 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 2.

76 NA, MH 95/32, Memorandum from E Mapother to the sub-committee appointed to consider possible developments arising out of the Mental Treatment Act of 1930, p. 1.

77 Edgar Jones, ‘Aubrey Lewis, Edward Mapother and the Maudsley’, in K Angel, E Jones and M Neve (eds), European psychiatry on the eve of war: Aubrey Lewis, the Maudsley Hospital and the Rockefeller Foundation in the 1930s, London, Wellcome Trust Centre for the History of Medicine at UCL, 2003, pp. 3–38, p. 23.

78 BRHA, C/12/4, E Mapother, `Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry', March 1931, p. 6.

79 NA, MH 95/32, Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control, 8 July 1932, p. 5.

80 LMA, Published minutes of the London County Council, 18 Feb. 1908, p. 282; Bond, op. cit., note 72 above.

81 NA, MH 58/224, F J Willis, Memorandum on the Report of Sir C Cobb's Committee, 6 Oct. 1922, p. 3; ‘Action by the Ministry of Health’, 1 Aug. 1922.

82 Adolf Meyer, ‘The contributions of psychiatry to the understanding of life problems’, [1921], in The collected papers of Adolf Meyer, vol. 4, p. 1, quoted in Jack D Pressman, Last resort: psychosurgery and the limits of medicine, Cambridge University Press, 1998, p. 18.

83 Andrew Scull, Madhouse: a tragic tale of megalomania and modern medicine, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2005, pp. 112–15.

84 ‘Notes and News’, J. Ment. Sci., 1923, 69: 552–9, on p. 558.

85 Ibid.

86 ‘Laboratory research in mental disease’, Lancet, 1925, 2: 232–3, p. 233.

87 Andrew Scull, ‘Focal sepsis and psychosis: the career of Thomas Chivers Graves, BSc, MD, FRCS, MRCVS (1883–1964)’, in Freeman and Berrios (eds), op. cit., note 4 above, pp. 517–36.

88 E Mapother, ‘Discussion on the prophylaxis of mental disorder’, Br. med. J., 1925, 2: 781–8, on p. 785.

89 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 4. F L Golla, ‘The functions of the Central Pathological Laboratory of the London County Mental Hospitals’, Arch. Neurol. Psychiatry, 1927, 9: 1–3.

90 BRHA, C/12/4, E Mapother, ‘Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry’, March 1931, pp. 1, 32.

91 Jones, op. cit., note 77 above, p. 20; Hayward, op. cit., note 10 above.

92 NA, FD 1/2411, E Mapother to Sir Walter Fletcher, 20 July 1932.

93 Rockefeller Archive (hereafter RA), 1.1 401A 19 255, Memo from D P O'Brien to Alan Gregg, 1 March 1938, p. 2.

94 Uwe Henrik Peters, ‘The emigration of German psychiatrists to Britain’, in Freeman and Berrios (eds), op. cit., note 4 above, pp. 565–80, p. 566.

95 Aubrey Lewis, ‘Henry Maudsley: his work and influence’, J. Ment. Sci., 1951, 97: 259–77, on p. 274.

96 Rockefeller Archive, 1.1 401A 19 253, Memo E Mapother to Alan Gregg, Jan. 1936, p. 1.

97 RA, 1.1 401A 19 255, Memo from D P O'Brien to Alan Gregg, 11 Mar. 1938.

98 Ibid.

99 Mott, op. cit., note 21 above, p. iii.

100 NA, MH 95/32, A H Trevor and C Hubert Bond, ‘Official visit on behalf of the Board of Control’, 25 Oct. 1923, p. 4.

101 S E Hague, ‘The Hospital today’, Bethlem and Maudsley Gazette, 1953, 1: 47–8; Henry Rollin, Festina lente: a psychiatric Odyssey, London, British Medical Journal, 1990, pp. 20–2.

102 BRHA, C/12/4, E Mapother, ‘Appeal for the endowment of an institute of psychiatry’, March 1931, p. 1.

103 RA, 1.1 401A 19 254, Memo from D P O'Brien to Alan Gregg, 12 Jan. 1938, p. 2.

104 RA, 1.1 401A 19 255, Memo from D P O'Brien to Alan Gregg, 11 Mar. 1938.

105 NA, MH 95/32, Memorandum from E Mapother to the sub-committee appointed to consider possible developments arising out of the Mental Treatment Act of 1930, p. 3.

106 RA, 1.1 401A 19 254, Memo from D P O'Brien to Alan Gregg, 12 Jan. 1938, p. 9.

107 Maarten Derksen, ‘Science in the clinic: clinical psychology at the Maudsley’, in G C Bunn, A D Lovie and G D Richards (eds), Psychology in Britain: historical essays and personal reflections, pp. 267–89, Leicester, BPS Books, 2001, p. 271.

108 Institute of Psychiatry, Report 1949–1950, p. 3, held in Institute of Psychiatry Library.

109 NA, MH95/32, W Rees Thomas and Ruth Darwin, Report, 29 Dec. 1938, p. 1.

110 NA, MH95/32, W Rees Thomas and C F Penton, Report, 12 Dec. 1946, p. 1.

111 ‘Voluntary mental patients’, Lancet, 1924, 2: 920.

112 Niall McCrae, ‘ “A violent thunderstorm”: cardiazol treatment in British mental hospitals’, Hist. Psychiatry, 2006, 17: 67–90.

113 William Sargant, The unquiet mind, London, Heinemann, 1967, p. 53.

114 Ibid, pp. 52–3.

115 William Sargant and Eliot Slater, An introduction to physical methods of treatment in psychiatry, Edinburgh, E & S Livingstone, 1944, p. 1.

116 Ibid., p. 12.

117 Ibid., pp. 2, 12, 14.