Abstract

The PU.1 transcription factor is a key regulator of hematopoietic development, but its role at each hematopoietic stage remains unclear. In particular, the expression of PU.1 in hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) could simply represent “priming” of genes related to downstream myelolymphoid lineages. By using a conditional PU.1 knock-out model, we here show that HSCs express PU.1, and its constitutive expression is necessary for maintenance of the HSC pool in the bone marrow. Bone marrow HSCs disrupted with PU.1 in situ could not maintain hematopoiesis and were outcompeted by normal HSCs. PU.1-deficient HSCs also failed to generate the earliest myeloid and lymphoid progenitors. PU.1 disruption in granulocyte/monocyte-committed progenitors blocked their maturation but not proliferation, resulting in myeloblast colony formation. PU.1 disruption in common lymphoid progenitors, however, did not prevent their B-cell maturation. In vivo disruption of PU.1 in mature B cells by the CD19-Cre locus did not affect B-cell maturation, and PU.1-deficient mature B cells displayed normal proliferation in response to mitogenic signals including the cross-linking of surface immunoglobulin M (IgM). Thus, PU.1 plays indispensable and distinct roles in hematopoietic development through supporting HSC self-renewal as well as commitment and maturation of myeloid and lymphoid lineages.

Introduction

Transcription factors play a major role in hematopoietic lineage determination and differentiation.1,2 The ETS family transcription factor PU.1 (Spi-1) is one of the most important regulators of hematopoietic lineage development. PU.1 is highly expressed in B and myelomonocytic cells,3 and in their precursors such as pro-B cells and granulocyte/monocyte progenitors (GMPs).4 More immature hematopoietic precursors including hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs), and common lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) also express PU.1 at a low level.4 These precursor populations “promiscuously” express other critical transcription factors including megakaryocyte/erythroid (MegE)–related GATA-1 and GATA-2, and granulocyte-related CCAAT enhancer-binding protein α (C/EBPα).5,6 PU.1 expression at these early hematopoietic stages may be due to “lineage priming,”7 which presumably represents a selective open chromatin form characteristic of early oligopotent stages.5,6 In fact, we have reported that some myeloid genes including lysozyme M were expressed in functional HSCs with long-term reconstitution potential.8 Therefore, at these stages, it has been hypothesized that the low levels of PU.1 transcripts are “sterile,” which may not have significant development-related functions, but may facilitate immediate lineage-specific transcription following internal or external lineage instructive cues.

PU.1 can activate the expression of myeloid cytokine receptors such as the granulocyte/macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor α (GM-CSFRα), macrophage CSF receptor (M-CSFR), and granulocyte CSF receptor (G-CSFR),9-11 as well as the lymphoid-specific interleukin-7 receptor α (IL-7Rα),12 whose signals usually provide permissive but not instructive effect for lympho-myeloid lineage commitment.13-17 Nonetheless, PU.1 can play an instructive role in hematopoietic lineage decisions. Enforced PU.1 in a multipotent myeloid cell line induced macrophage differentiation.18 In primary fetal liver progenitors, the introduction of PU.1 at a high level induced macrophage differentiation, whereas a low level of PU.1 induced B-cell differentiation.19 This process could be modulated by other transcription factors. GATA-1 can inhibit PU.1 function,20-22 while PU.1 blocks binding of GATA-1 to DNA.23 PU.1 also can negatively regulate the expression of GATA-2, which is important for MegE as well as mast cell development.24 Therefore, the quantity and progenitor-specific expression of PU.1 should be critical for its functions in lineage determination.

In turn, the loss of PU.1 function severely impairs hematopoietic development. In humans, loss-of-function mutations in the PU.1 gene have been found in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML),25 which is characterized by maturation arrest of myeloblasts. In mice, complete disruption of PU.1 resulted in embryonic and/or newborn lethality.26,27 In PU.1 knock-out mice, the most profound deficit was in development of neutrophils/monocytes and B cells reflecting the physiologic expression patterns of PU.1. Of interest, T- and natural killer (NK) cell development was also severely impaired in PU.1 knock-out mice,28,29 but MegE development was intact.26,27 PU.1-deficient fetal liver cells failed to contribute to myeloid and lymphoid development when transplanted into lethally irradiated hosts,30 presumably due to their impaired ability to home to and colonize the bone marrow,31 but this phenomenon raised a possibility that PU.1 plays a critical role in maintenance of HSCs. A recent report showed that PU.1–/– fetal liver HSCs lacked Thy-1.1 expression, which is a marker of long-term HSCs in C57B6-Thy1.1 mice.32 While such studies were highly informative, the role of PU.1 in each stage of hematopoiesis cannot be directly addressed by this system since PU.1 expression is initiated as early as the extraembryonic hematopoietic stage at the aorta-gonad-mesonephros (AGM) region,33 and the loss of PU.1 might affect all subsequent hematopoietic development in PU.1-deficient mice.30

Here, we used a conditional knock-out system34 targeting the PU.1 locus, in which the expression of Cre can excise the PU.1 allele flanked (floxed) by loxP sites. By using a multicolor fluorescence cell sorting (FACS) system, we purified and analyzed HSCs as well as lineage-restricted progenitors including CLPs,35,36 CMPs, GMPs, and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitors (MEPs)4,37 in order to locate the stage-specific effect of PU.1 disruption in bone marrow hematopoiesis. We found that in vivo disruption of PU.1 in bone marrow HSCs resulted in functional impairment in their ability to compete with wild-type HSCs as well as to develop CMPs and CLPs. The expression of PU.1 at the HSC stage, therefore, does not merely represent “lineage priming” but it is essential to maintain intrinsic functional properties of HSCs. Furthermore, disruption of PU.1 at the level of myeloid progenitors also inhibited their maturation. Our data show that PU.1 supports hematopoiesis through multiple stage-specific functions.

Materials and methods

Mice

Mx1-Cre transgenic mice and CD19-Cre knock-in mice were kindly provided by Klaus Rajewsky. Mx1-Cre mice were bred with PU.1F/F mice to obtain Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F mice. Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F mice were further bred with PU.1–/+ mice to obtain Mx1-Cre × PU.1–/F mice. Recombination was induced in newborn mice by single intraperitoneal injection of poly-inosinic–polycytidylic acid (pI-pC, 125 μg) 1 to 2 days after birth. In some experiments, PU.1F/F mice were bred to CD19-Cre mice in order to specifically delete the PU.1 gene in early B cells. PU.1GFP/+ mice were generated as described previously.38 All of these mouse strains used were crossed into C57B6 mice for at least 7 generations. Mice were bred and maintained in the Research Animal Facility at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in accordance with the guidelines.

Generation of PU.1F/F and PU.1–/+ mice

An 11–kilobase (kb) genomic clone of the murine PU.1 gene was used to generate the conditional targeting construct. A genomic fragment containing exons 3 to 5 of PU.1 was subcloned into the BamHI site of pL2XR vector (derived from the pL2-Neo, obtained from Hua Gu, Department of Microbiology, Columbia University, New York, NY and K. Rajewsky, CBR Institute for Biomedical Research and Department of Pathology, Department of Cancer Biology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA) containing the PGK-Neo cassette flanked by loxP sites. A loxP recombination site had been previously introduced in the intronic region between exons 3 and 4 of the PU.1 gene. The targeting construct was linearized with NotI, and transfected into embryonic stem (ES) cells according to established procedures. Analysis of the homologous recombinant ES clones was performed by Southern blot analysis of BamHI-digested genomic DNA, using a 0.5-kb BamHI/KpnI 3′ flanking probe. Injection of a PU.1F/+ ES clone into C57/B6 blastocysts generated chimeras that transmitted the mutation to the germ line. Breeding heterozygous mice generated PU.1F/F homozygous mice that were born at the expected mendelian ratio.

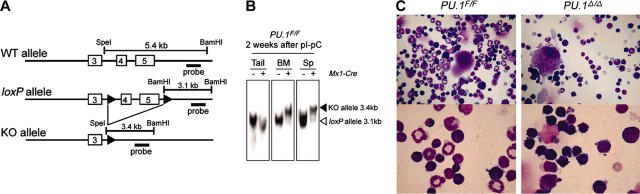

Genotyping and assessment of recombination was performed by Southern blot analysis of tail snip DNA(10 μg) digested with BamHI and SpeI, hybridizing to a probe containing the 1.3-kb BamHI/EcoRI fragment derived from the 3′ region of the PU.1 gene (Figure 3). The fragment sizes hybridizing to the probe are wild type, 5.4 kb; loxP, 3.1 kb; and knock-out, 3.4 kb.

Figure 3.

Generation and characterization of conditional PU.1 knock-out mice. (A) Generation of a conditional targeted allele of the murine PU.1 gene. Cre recombination sites (loxP, black arrowheads) were inserted distal to the SpeI site in intron 3 and 435 base pair (bp) distal to the end of exon 5 as indicated. Shown are the predicted structures of the wild-type allele (WT), the targeted allele with the loxP sites (loxP), and the allele after Cre-mediated recombination, in which exons 4 and 5 have been deleted (KO). The relative location of the probe used in Southern blot analysis (a 1.3-kb BamHI/EcoRI fragment) is also shown. (B) Southern blot analysis of Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F mice 2 weeks following pI-pC injection. BM indicates bone marrow. (C) Morphology of adult bone marrow cells in PU.1F/F (left) or Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F (right) mice 3 weeks after injection of pI-pC (May-Giemsa staining; top panels: 400×; bottom panels: 1000×).

By expressing Cre in a PU.1F/+ ES clone, we developed a strain of PU.1–/+ mice consisting of one wild-type allele and one PU.1 knock-out allele. Breeding these mice did not result in viable pups with a PU.1–/– genotype, suggesting that, like other nonconditional PU.1 knock-out models,26,27 the PU.1–/– genotype results in embryonic and/or perinatal lethality. However, day-14.5 PU.1–/– embryos could be obtained with near Mendelian frequency.

Antibodies, cell staining, and cell sorting

To sort HSCs and myeloid progenitors, E14.5 fetal liver or adult bone marrow cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated anti-CD34 (RAM34), phycoerythrin (PE)–conjugated anti–Fcγ receptor II/III (FcγRII/III, 2.4G2), allophycocyanin (APC)–conjugated anti–c-Kit (2B8), and biotinylated anti–stem cell antigen 1 (Sca-1, E13-161-7) monoclonal antibodies (all from Pharmingen, San Diego, CA); PE–cyanin 5 (Cy5)–conjugated anti–IL-7Rα chain monoclonal antibodies (A7R34; eBioscience, San Diego, CA); and PE-Cy5–conjugated rat antibodies, specific for the following lineage markers: CD3 (CT-CD3), CD4 (RM4-5), CD8 (5H10), B220 (6B2), Gr-1 (8C5), and CD19 (6D5; all from Caltag, Burlingame, CA), followed by avidin-APC-Cy7 (Caltag). Fetal liver and bone marrow HSCs were sorted as IL-7Rα–Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34+ and IL-7Rα–Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34–/lo populations, respectively. To sort side population (SP) cells, adult bone marrow cells were incubated with Hoechst 33342 (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) before antibody staining as reported.39 Myeloid progenitors were sorted as IL-7Rα–Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+CD34+FcγRII/IIIlo (CMPs), IL-7Rα–Lin–Sca-+–c-Kit+CD34+FcγRII/IIIhi (GMPs), and IL-7Rα–Lin–Sca-1–c-Kit+CD34–FcγRII/IIIlo (MEPs) as described previously.4,37 Sorting of CLPs was accomplished by staining E14.5 fetal liver or bone marrow cells with biotinylated anti–IL-7Rα chain (A7R34; eBioscience), FITC-conjugated anti–Sca-1 (E13-161-7), APC-conjugated anti–c-Kit (2B8; both from Pharmingen), and PE-Cy5–conjugated lineage antibodies (Caltag), followed by avidin-PE (Caltag). CLPs were sorted as IL-7Rα+Lin–Sca-1loc-Kitlo population.35,36 Stem and progenitor cells were double-sorted using a highly modified double laser (488 nm/350 nm Enterprise II + 647 nm Spectrum) high-speed FACS (Moflo-MLS; Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO). For all analyses and sorts, dead cells were excluded by propidium iodide staining. For single-cell assays, cells were directly sorted into 60-well Terasaki plates or 96-well plates by using an automatic cell deposition unit (ACDU) system. Data were analyzed with FlowJo software (Treestar, San Carlos, CA).

Cell cultures

For clonogenic assays, single stem and progenitor cells were sorted into 96-well plates containing methylcellulose medium (Methocult H4100; Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC) supplemented with 30% fetal calf serum (FCS), 1% bovine serum albumin, and 2 mM l-glutamine (Stem Cell Technologies) by using an ACDU system. Cytokines such as murine stem cell factor (SCF, 20 ng/mL), IL-3 (20 ng/mL), GM-CSF (10 ng/mL), G-CSF (10 ng/mL), erythropoietin (Epo, 2 unit/mL), and thrombopoietin (Tpo, 10 ng/mL; all from R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) were added at the initiation of cultures. Colonies were enumerated under an inverted microscope consecutively from days 4 to 7. Colony-forming unit (CFU)–mix, including CFU–granulocyte erythroid macrophage megakaryocyte (GEM-Meg), CFU–granulocyte erythroid macrophage (GEM), and CFU–granulocyte erythroid megakaryocyte (GEMeg), was determined by May-Giemsa staining of cells plucked as individual colonies using fine-drawn Pasteur pipettes. All cultures were incubated at 37°C in a humidified chamber under 5% CO2.

Bone marrow reconstitution assay

Ly5.1 congenic C57/B6 mice at 6 to 8 weeks of age (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were γ-irradiated with a single lethal dose of 950 cGy and were used as recipients. One-thousand fetal liver HSCs from E14.5 PU.1–/– embryos (Ly5.2 C57/B6) were injected intravenously into each irradiated recipient mouse together with 2 × 105 Ly5.1 adult bone marrow cells. As controls, 100 fetal liver HSCs from PU.1–/+ littermates (Ly5.2 C57/B6) were also transplanted into each irradiated recipient together with 2 × 105 Ly5.1 adult bone marrow cells. Mice that underwent transplantation were kept in sterilized cages with drinking water containing antibiotics. To analyze chimerism in reconstituted mice, bone marrow cells were stained with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (Ly5.2), biotinylated anti-CD45.1 (Ly5.1), PE-conjugated anti–Sca-1 (E13-161-7), and APC-conjugated anti–c-Kit (2B8) (Pharmingen), followed by avidin-APC-Cy7 (Caltag).

Single PU.1-GFP+CD34– HSC (Ly5.2 C57/B6) was also transplanted into each irradiated recipient mouse together with 2 × 105 Ly5.1 adult bone marrow cells. The chimerism in reconstituted mice was analyzed by staining blood cells with FITC-conjugated anti-CD45.2 (Ly5.2), PE-conjugated anti–Gr-1, APC-conjugated anti-CD3, and APC-Cy7–conjugated anti-B220.

Conditional PU.1 disruption in purified stem and progenitor cells

A Cre cDNA was subcloned into the EcoRI site of MSCV-ires-EGFP vector. The virus supernatant was obtained from the cultures of 293T cells cotransfected with the target retrovirus vector, gag-pol– and vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSV-G)–expression plasmids using a standard CaPO4 coprecipitation method. CMPs and GMPs purified from PU.1F/F mice were cultured for 48 hours onto a recombinant fibronectin fragment–coated culture dish (RetroNectin dish; Takara, Tokyo, Japan) with 1 mL of the virus supernatant containing SCF (20 ng/mL) and IL-11 (10 ng/mL). At the completion of transduction, cells positive for green fluorescent protein (GFP) were purified by FACS and subjected to further analyses. The excision of loxP alleles was assessed by genomic polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assay (Table S1; see the Supplemental Table link at the top of the online article, at the Blood website).

Analysis of gene expression from total RNA

Total RNA extracted from 100 cells (Figure 5B) or 2000 cells (Figures 6B, 7E) for each population was subjected to reverse-transcriptase (RT)–PCR analyses as described previously.40 Primer sequences and PCR protocols for each specific gene are shown in Table S1. A quantitative real-time PCR assay for IL-7Rα was performed with ABI PRISM 7700 Sequence Detector (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The forward primer was 5′-AAGTTTTCTGCCCAATGATCTTCC-3′, the reverse primer was 5′-CTCAGGCGAGCGGTTTGC-3′, and the probe was 5′-FAM-AGCGGCTCTGTGTCCCTGTGTCTCC-TAMRA-3′. Rodent glyceraldehyde phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) control reagents (Applied Biosystems) were used as an internal control.

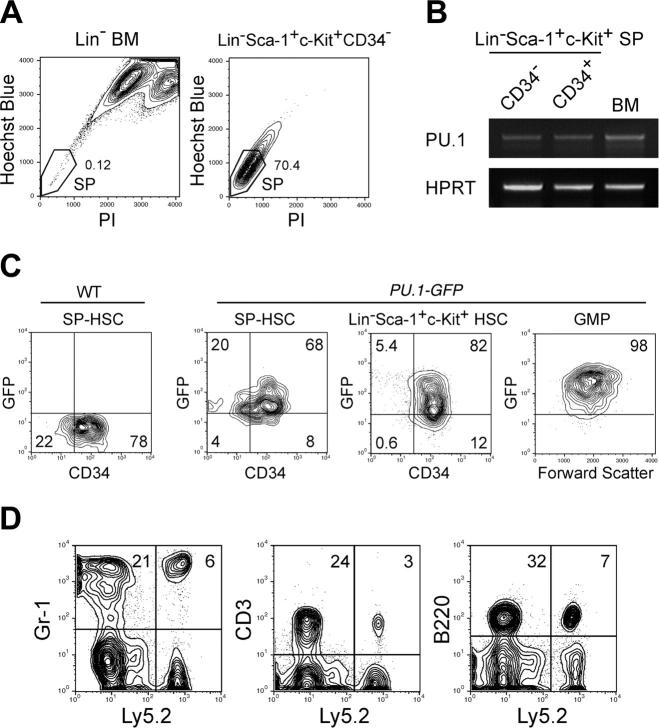

Figure 5.

PU.1 is expressed in functional HSCs with long-term reconstituting potential. (A) Sorting gates for the SP fraction. The vast majority of Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34– cells possessed the SP profile. (B) RT-PCR analysis of PU.1 mRNA in CD34+ or CD34– SP HSCs. HPRT indicates hypoxanthin phosphoribosyltransferase. (C) Expression of GFP in HSCs and GMPs purified from PU.1GFP/+ mice. The vast majority of Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ HSCs and SP HSCs expressed PU.1-GFP irrespective of CD34 expression at the single-cell level. GMPs expressed GFP at a higher level compared with HSCs. (D) Ly5.2+ donor type Gr-1+, CD3+, and B220+ cells were successfully reconstituted in a mouse that received a transplant of a single CD34–PU.1-GFP+ HSC. Multilineage reconstitution has been maintained for more than 20 weeks.

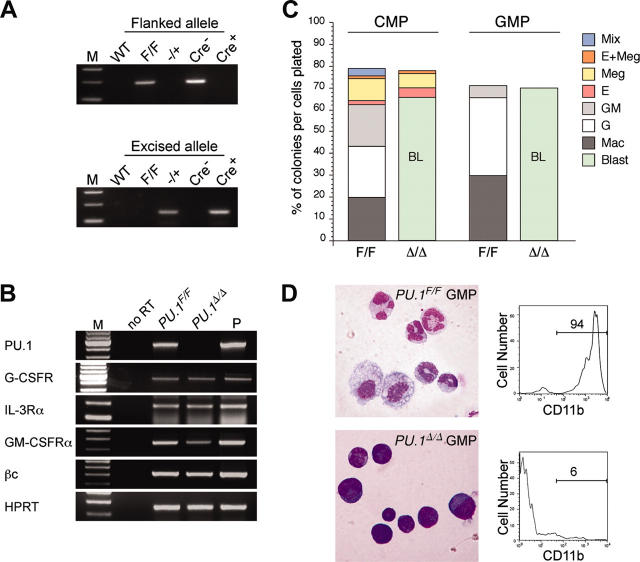

Figure 6.

PU.1 disruption at the CMP or GMP stage. (A) PCR analysis of flanked PU.1 alleles in control and Cre-transduced GMPs. The flanked PU.1 allele became undetectable after the Cre transduction into PU.1F/F GMPs. M indicates the molecular weight marker. (B) RT-PCR analyses of cytokine receptors in PU.1Δ/Δ CMPs. M indicates the molecular weight marker; P, the positive control. (C) Myeloid colony assays of single sorted PU.1F/F and PU.1Δ/Δ CMPs/GMPs in the presence of SCF, GM-CSF, IL-3, Epo, and Tpo. PU.1Δ/Δ CMPs and GMPs could not form mature M, G, or GM colonies, but formed myeloblast colonies. BL indicates blast. (D) PU.1Δ/Δ GMPs formed colonies composed mainly of immature myeloid cells (May-Giemsa staining, 600×), which expressed only low levels of CD11b.

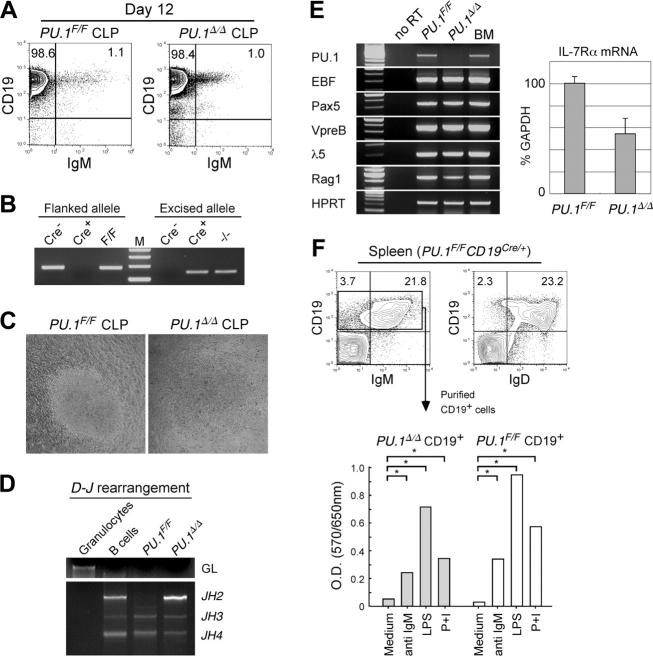

Figure 7.

PU.1 disruption at the CLP stage. (A) B-cell differentiation assays of PU.1F/F and PU.1Δ/Δ CLPs in the presence of IL-7. PU.1F/F and PU.1Δ/Δ CLPs gave rise to almost equal numbers of CD19+IgM+ mature B cells after 12 days of culture on OP9 cells in the presence of IL-7. (B) PU.1Δ/Δ CLP-derived B-cell progeny completely excised floxed alleles. (C) PU.1F/F and PU.1Δ/Δ CLPs gave rise to similar sizes of B-cell colonies in response to IL-7 after 12 days in culture. (D) Both PU.1Δ/Δ and PU.1F/F CLP-derived B cells rearranged their IgH gene. (E) RT-PCR analyses of B-cell–related genes in PU.1F/F and PU.1Δ/Δ B cells (left). IL-7Rα transcripts were quantitated by a real-time PCR analysis (right). Error bars indicate SD. (F) Analysis of spleen B cells developed in PU.1F/FCD19Cre/+ mice. PU.1Δ/Δ CD19+ B cells expressed normal levels of IgM and IgD (upper panels). Purified PU.1Δ/Δ CD19+ B cells from PU.1F/FCD19Cre/+ mice displayed normal proliferative response to mitogenic agents including anti-IgM antibodies, LPS, and PMA plus ionomycin (P+I) determined by an MTT assay (bottom). *P < .05.

Immunoglobulin heavy chain (IgH) gene rearrangement analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted from 4000 double-sorted CD19+IgM+ cells by incubation at 56°C for 45 minutes in 50 μL1 × PCR buffer containing 0.5% Tween 20 and 100 μg/mL proteinase K, followed by 10 minutes at 94°C to inactivate proteinase K. PCR primers specific for DHQ52 element were used to amplify rearranged IgH D-J as described previously.41 Primer sequences are provided in Table S1. PCR products were separated on a 1.5% agarose gel.

Proliferation assays

Splenic CD19+ B cells (4 × 105) purified from PU.1F/F × CD19Cre/+ or control PU.1F/F mice were cultured for 48 hours in 96-well flat-bottom plates in quadruplicate in the presence of anti-IgM antibodies (50 μg/mL) (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA), lipopolysaccharide (LPS, 25 mg/mL; Sigma, St Louis, MO), and phorbol myristate acetate (PMA, 300 ng/mL; Sigma) + ionomycin (600 ng/mL; Calbiochem, San Diego, CA). Cell proliferation was measured by the methyl-thiazol tetrazolium (MTT) cell proliferation assay.42

Imaging

Cytologic images were captured on a Nikon Eclipse E400 microscope (Figures 2, 3, and 6) or a Nikon Eclipse TS100 inverted microscope (Figure 7) equipped with a Nikon DS-5M-L1 color digital camera (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Nikon 10 ×/22 NA ocular lenses and CFI PLAN APO (10 ×/0.45 NA [Figure 7], 40 ×/0.95 NA [Figure 3C, top], 60 ×/0.95 NA [Figures 2A and 6], and 100 × oil/1.40 NA [Figures 2E and 3C, bottom]) were used. Images were cropped in Adobe Photoshop 6.0 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA) and composed in Canvas 8 (ACD systems, Miami, FL).

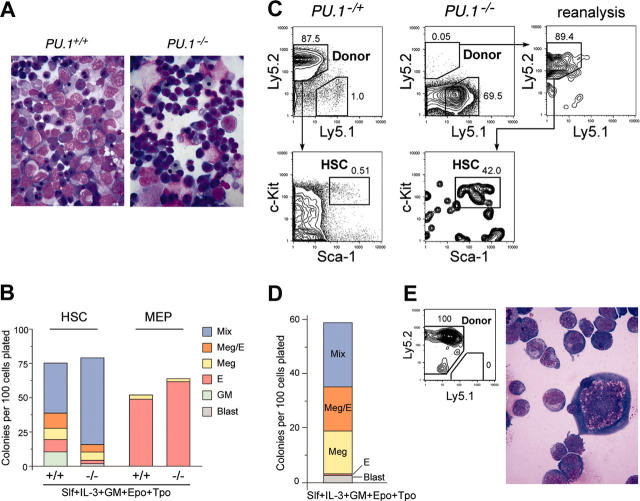

Figure 2.

Stem and progenitor activity of PU.1–/– fetal liver cells. (A) Morphology of E14.5 fetal liver cells of PU.1+/+ and PU.1–/– embryos (May-Giemsa staining, 600×). (B) The numbers of specific types of colonies derived from purified HSCs (left columns) and MEPs (right columns) from PU.1+/+ and PU.1–/– fetal livers. Note that in PU.1–/– cultures, there were no mature granulocytic and monocytic components that were replaced by immature myeloblastic cells. (C) Analysis of reconstitution activity of PU.1–/– fetal liver HSCs. Twelve weeks after injection of high doses (1000 cells) of PU.1–/– HSCs (Ly5.2+) into Ly5.1+ congenic lethally irradiated hosts, a minor population of donor-derived cells (Ly5.2+) of HSC phenotype (Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+) was detected. Control experiments using 100 PU.1–/+ fetal liver HSCs (Ly5.2+) as a donor demonstrated that nearly all of the recipient bone marrow cells were of donor origin. (D) Colony assay of purified secondary PU.1–/– HSCs. They displayed colony-forming activity almost equal to primary PU.1–/– HSCs (B). (E) A mixed colony derived from single secondary PU.1–/– HSC expressed the Ly5.2 donor maker, and contained erythroblasts and megakaryocytes and immature blastic myelomonocytic cells but not mature granulocytes or macrophages (May-Giemsa staining, 1000×).

Results

PU.1-deficient fetal liver hematopoiesis displays a maturation arrest at the transition from the HSC to CLP and CMP stages

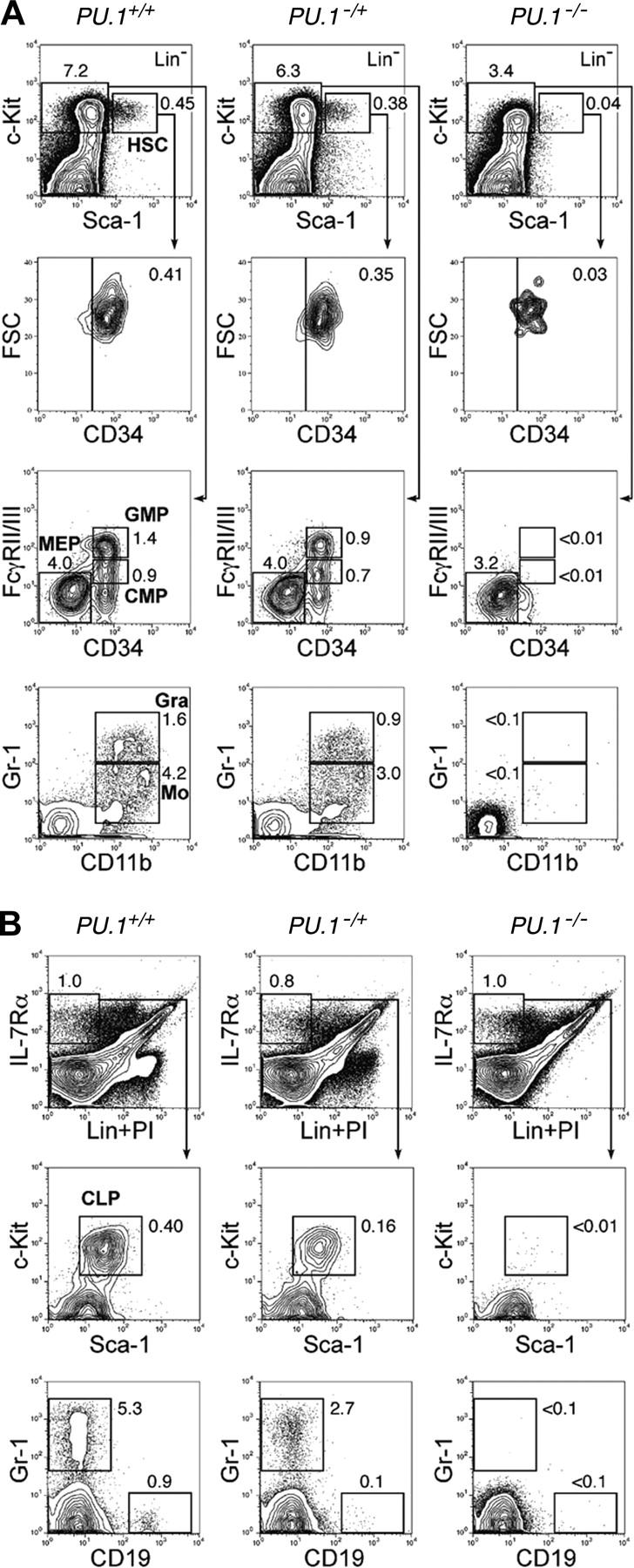

A strain of PU.1–/+ mice consisting of one wild-type allele and one PU.1 knock-out allele was established by expressing Cre in a PU.1F/+ ES clone. We then bred PU.1–/+ mice to obtain PU.1–/– embryos. In order to precisely define the stage at which myeloid maturation is blocked in PU.1-deficient fetal liver hematopoiesis, we first performed multicolor FACS analyses. On embryonic day 14.5 (E14.5), the number of fetal liver Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ HSCs was decreased up to 10-fold in PU.1–/– embryos compared with that in PU.1+/+ embryos (Table 1). These HSCs expressed a normal level of CD34, which is expressed in fetal liver HSCs with long-term reconstitution activity33 (Figure 1A). E14.5 normal (PU.1+/+) fetal liver has CMPs and GMPs as we previously reported.37 Strikingly, both CMPs and GMPs were undetectable in PU.1–/– fetal liver, resulting in the absence of CD11b+Gr-1hi neutrophils or CD11b+Gr-1lo monocytes. In contrast, the number of MEPs relatively increased in PU.1–/– fetal liver (Figure 1A; Table 1). The myeloid phenotype of PU.1–/– fetal liver is compatible with a previous report in another PU.1–/– strain.32 In the lymphoid pathway, PU.1–/– fetal livers possessed almost identical numbers of Lin–IL-7Rα+ cells. However, these cells did not contain the Sca-1loc-Kitlo population that represents the fetal liver counterpart of adult bone marrow CLPs36 (Figure 1B; Table 1). These data are consistent with the predominance of erythroid progenitors and absence of myeloid cells in PU.1–/– fetal liver as assessed by morphology (Figure 2A). In PU.1–/+ fetal liver, the numbers of HSC, CMP, GMP, and CLP populations decreased but were still present, suggesting that the PU.1 effect is dose dependent.

Table 1.

Percentages of hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells in PU.1 nonconditional and conditional knockout mice

|

Positive percent for each fraction

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genotype | Age | HSC | CLP | CMP | GMP | MEP | Granulocyte | Monocyte |

| PU.1-/- | E14.5 | 0.036* | <0.01* | <0.01* | <0.01* | 3.98 | <0.01* | 0.05* |

| PU.1-/+ | E14.5 | 0.41 | 0.16 | 0.66 | 0.88 | 3.96 | 0.72 | 2.98 |

| PU.1+/+ | E14.5 | 0.43 | 0.35 | 0.75 | 1.21 | 3.50 | 1.08 | 6.48 |

| Mx1-Cre+PU.1F/F | 2 wk | 0.10 | <0.01* | 0.012* | 0.032* | 2.33* | 2.49* | 4.07 |

| PU.1F/F (Cre-) | 2 wk | 0.12 | 0.068 | 0.75 | 0.37 | 0.90 | 7.14 | 3.58 |

| Mx1-Cre+ PU.1F/F | 4 wk | 0.51 | <0.01* | 0.027* | 0.027* | 14.71* | 3.07 | 9.42 |

| PU.1F/F (Cre-) | 4 wk | 0.35 | 0.11 | 0.75 | 0.59 | 1.44 | 7 | 9.55 |

| Mx1-Cre+ PU.1F/F | 6 wk | 0.22 | 0.076* | 0.16* | 0.88 | 2.33* | 10.25 | 11.48 |

| PU.1F/F (Cre-) | 6 wk | 0.29 | 0.19 | 0.74 | 1.43 | 1.08 | 8.98 | 8.17 |

For conditional disruption of floxed PU.1 alleles, pl-pC (single dose of 125 μg) was intraperitoneally injected in Mx1-Cre+ or Mx1-Cre- PU.1F/F mice at 1 to 2 days after birth.

P < .05.

Figure 1.

PU.1 knock-out fetal liver HSCs are arrested at the transition to the common myeloid and lymphoid progenitor stages. Multicolor FACS analysis was performed in E14.5 fetal livers from PU.1+/+, PU.1–/+, and PU.1–/– embryos. (A) The top panels demonstrate the Sca-1/c-Kit profile of Lin– cells. PU.1–/– fetal liver has a decreased number of Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34+ HSCs. PU.1–/– fetal liver lacks CMPs and GMPs as well as their progeny, mature monocytic (CD11b+/Gr-1lo) and granulocytic (CD11b+/Gr-1hi) populations. (B) PU.1+/+, PU.1–/+, and PU.1–/– fetal livers have almost equal numbers of Lin–IL-7Rα+ cells. PU.1–/– fetal liver lacks Lin–IL-7Rα+Sca-1loc-Kitlo CLPs and CD19+ early B cells. In both analyses, PU.1–/+ fetal liver has intermediate numbers of myeloid and lymphoid progenitors. Numbers in each panel represent percentages of the gated population in whole fetal liver cells. FSC indicates forward scatter; Gra, granulocytes; Mo, monocytes; and Lin, lineage.

To verify these phenotypic definitions of myelo-erythroid progenitors, we tested the colony-forming activity of single HSCs and MEPs purified from PU.1+/+ or PU.1–/– fetal liver. As shown in Figure 2B, purified PU.1+/+ and PU.1–/– MEPs both exclusively gave rise to MegE-related colonies, and therefore were functionally equivalent. PU.1+/+ HSCs gave rise to various types of myelo-erythroid colonies, half of which were mixed colonies that contain all myelo-erythroid components.37 In contrast, PU.1–/– HSCs dominantly gave rise to immature mixed colonies that did not contain mature neutrophils or macrophages. In these colonies, undifferentiated myeloblasts were predominant in addition to normal MegE cells (not shown), indicating that PU.1–/– HSCs were at least multipotent for myelo-erythroid lineages. These data collectively suggest that HSCs are present in PU.1–/– fetal liver, but they are unable to differentiate into CMPs or CLPs in vivo.

PU.1–/– fetal liver HSCs can home to the bone marrow but have a defect in long-term reconstitution of adult bone marrow

It was reported that E14.5 PU.1–/– hematopoietic cells enriched for progenitors (AA4.1+) were defective in their ability to contribute to long-term reconstitution of congenic recipient mice in competitive repopulation assays.30,32 In addition, these PU.1–/– progenitors were impaired in their ability to home to and colonize the bone marrow.31 We wished to extend these studies by assessing the function of purified HSCs from PU.1–/– fetal livers. Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34+ HSCs (103) purified from PU.1–/– fetal livers (C57B6-Ly5.2) (Figure 1A) were injected into lethally irradiated congenic C57B6-Ly5.1 recipients along with 2 × 105 Ly5.1 bone marrow cells. Consistent with the previous report,31 we could not detect Ly5.2+ cells in peripheral blood after transplantation (not shown), indicating that PU.1–/– HSCs cannot contribute to peripheral white blood cell reconstitution in the recipient mice. Of note is that erythrocytes and platelets, the progeny of MEPs, do not express Ly markers, and therefore this analysis cannot assess their contribution to the peripheral blood. We killed recipient animals 3 months after transplantation. As shown in Figure 2C, a small fraction (0.02%-0.05%) of Lin– bone marrow cells were derived from the Ly5.2+ PU.1–/– donor HSCs in all 5 mice analyzed. In contrast, all control animals receiving 100 PU.1–/+ fetal liver HSCs reconstituted more than 80% of bone marrow cells. Almost 40% of the Ly5.2+ PU.1–/– cells displayed the Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ HSC phenotype. These secondary PU.1–/– HSCs were capable of forming Ly5.2+ mixed and MegE-related colonies in vitro (Figure 2D-E). PU.1–/– donor-derived HSCs disappeared 6 months after transplantation in all 6 mice analyzed (not shown). These data suggest that at least a fraction of fetal liver PU.1–/– HSCs can home to the bone marrow of lethally irradiated recipient mice, but cannot maintain the HSC pool or contribute to blood myelopoiesis or lymphopoiesis.

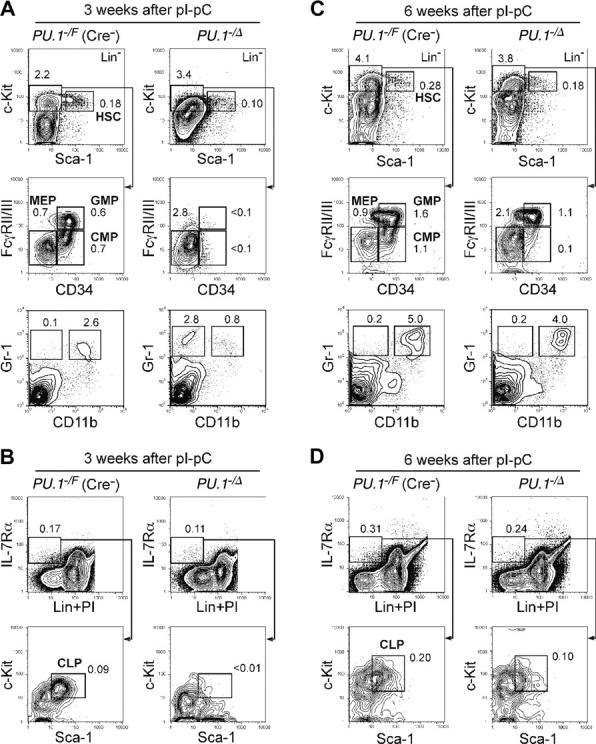

Bone marrow HSCs conditionally disrupted with PU.1 in situ also exhibit an arrest at the transition from the HSC to CLP and CMP stages, and are outcompeted by normal HSCs

Studies of PU.1–/– fetal liver cells strongly suggest that PU.1 plays a role in both maintenance as well as differentiation of HSCs. The loss of PU.1 in knock-out animals, however, may affect embryonic HSC development, which itself may result in the loss of their long-term reconstitution activity. Therefore, to further evaluate the requirement of PU.1 at the HSC stage by a conditional PU.1 knock-out model, we generated a mouse harboring Cre recombinase recognition sites (“loxP” sites) flanking exons 4 and 5 of the murine PU.1 gene (Figure 3A).

We crossed mice harboring loxP-flanked PU.1 alleles (PU.1F/F) with a Mx1-Cre transgenic mouse strain, in which a high level of Cre recombinase is produced by treatment with the interferon inducer pI-pC, leading to recombination in the bone marrow at every stage of maturation.43,44 Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F mice were injected intraperitoneally with pI-pC within 2 days after birth. As shown in Figure 3B, the efficiency of PU.1 gene excision was higher than 95% in the bone marrow and spleen 2 weeks after pI-pC injection. We shall refer to pI-pC–treated Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F and Mx1-Cre × PU.1–/F mice as PU.1Δ/Δ and PU.1–/Δ, respectively, for the sake of brevity with the realization that a small fraction (< 5%) of hematopoietic cells have likely not excised the loxP allele.

In the absence of a Mx1-Cre transgene, we did not observe a significant difference in numbers of HSCs, progenitors, or mature myeloid cells among PU.1+/+, PU.1–/F, and PU.1F/F mice after pI-pC injection at the time points analyzed (2 weeks and later) (Table 1 and data not shown). In contrast, in PU.1Δ/Δ or PU.1–/Δ mice, profound effects were detected in the bone marrow 2 to 4 weeks after pI-pC injection (Table 1; Figure 4). At these time points, numbers of HSCs were somewhat decreased. Strikingly, there was a significant loss of CMPs and GMPs as well as mature myeloid cells in PU.1Δ/Δ and PU.1–/Δ mice, whereas MEPs were increased (Figure 4A). Gr-1+CD11b+ mature granulocytes disappeared, and a small number of Gr-1+CD11b– immature myeloid cells were seen (Figure 4A). Furthermore, Lin–IL-7Rα+ cells were easily detectable in PU.1Δ/Δ and PU.1–/Δ mice, but did not contain Sca-1loc-Kitlo CLPs (Figure 4B). In the bone marrow of PU.1Δ/Δ mice, erythropoiesis did not appear to be affected (Figure 3C). Thus, the block in differentiation following disruption of PU.1 in the bone marrow is quite similar to that observed in PU.1–/– fetal liver. However, by 6 weeks, the numbers of CLPs, CMPs, and GMPs as well as Gr-1+CD11b+ mature granulocytes in PU.1Δ/Δ or PU.1–/Δ mice began to recover (Table 1; Figure 4C-D), and at this point the majority of hematopoietic cells in the bone marrow or the spleen possessed the intact PU.1F alleles (data not shown). After this point, PU.1Δ/Δ mice never became neutropenic or leukemic during a one-year observation period. In summary, in PU.1Δ/Δ mice, PU.1–/– bone marrow HSCs cannot maintain hematopoiesis, and it is likely that a small fraction of HSCs that did not excise the PU.1F alleles progressively overgrew PU.1–/– HSCs, resulting in repopulation with a hematopoietic picture resembling PU.1F/F or PU.1+/+ adult mice.

Figure 4.

Conditional depletion of PU.1 in adult hematopoiesis. FACS analysis of Mx1-Cre × PU.1–/F mice 3 (A-B) and 6 (C-D) weeks after pI-pC injection. Three weeks after the injection, HSCs were decreased up to 5-fold, and CMPs and GMPs disappeared (A). At this time point, the vast majority of bone marrow cells excised loxP-flanked PU.1 alleles (not shown). Significant recovery of these cells was observed at 6 weeks (C), when the excised allele of PU.1 locus was undetectable (not shown). CLPs were eliminated 3 weeks following disruption of PU.1 (B), while they recovered at the 6-week time point (D). Numbers in each panel represent percentages of the gated population in whole bone marrow cells. Summarized data including results of pI-pC injection into Mx1-Cre × PU.1F/F mice are shown in Table 1.

Long-term HSCs express PU.1 at the single-cell level

We tested whether HSCs capable of self-renewal express PU.1 to maintain their population. The Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ CD34– fraction of bone marrow cells contains HSCs with long-term reconstitution activity at the single-cell level.45 Matsuzaki et al46 have reported that long-term reconstitution activity of Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ CD34– cells could be further enriched in the SP39 with a relatively strict gate. As shown in Figure 5A, Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34– bone marrow cells contained a significant fraction of SP cells. Purified Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ SP cells expressed PU.1 mRNA irrespective of the CD34 expression (Figure 5B). We further tested the regulation of PU.1 expression in HSCs by using PU.1-GFP mice, in which a GFP gene is knocked into the PU.1 locus.38 The vast majority of Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ and Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ SP HSCs in PU.1GFP/+ mice possessed GFP irrespective of CD34 expression, and GFP levels progressively increased as they stepped forward into the CMP and GMP stages (Figure 5C). CLPs also expressed PU.1 at the level similar to CMPs (not shown). We then transplanted single Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ CD34–PU.1-GFP+ cells into congenic hosts (C57B6-Ly5.1). More than 30% of mice that received transplants of single Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ CD34–PU.1-GFP+ cells displayed multilineage reconstitution, where the donor-derived hematopoiesis has been maintained for more than 13 weeks (Figure 5D). These data indicate that PU.1 is expressed in the majority of HSCs capable of self-renewal.

Disruption of PU.1 in committed myeloid progenitors (CMPs or GMPs) blocks their myelomonocytic differentiation

In order to test the requirement of PU.1 after completion of myeloid commitment, we transduced the Cre gene directly into purified PU.1F/F CMPs and GMPs via GFP-tagged retroviral vectors. Forty-eight hours after initiation of retroviral transduction, we purified GFP+ CMPs or GMPs to use in the following assays. As shown in Figure 6A, the PU.1 allele flanked by loxP sites was undetectable in PU.1F/F GMPs transduced with the Cre gene, indicating nearly complete excision of both PU.1F alleles. PU.1Δ/Δ (Cre-transduced) CMPs expressed normal levels of myeloid cytokine receptors including G-CSFR, IL-3Rα, and βc. The expression of GM-CSFRα mRNA was slightly reduced in PU.1Δ/Δ CMPs compared with PU.1F/F CMPs (Figure 6B). In the presence of a panel of cytokines, PU.1Δ/Δ CMPs and GMPs formed colonies as efficiently as their controls (Figure 6C). However, PU.1Δ/Δ GMPs gave rise to colonies composed only of myeloblasts. These myeloblasts did not express CD11b (Mac-1) (Figure 6D). PU.1Δ/Δ CMPs gave rise to MegE colonies as well as myeloblast colonies that appeared to replace GM-related colonies formed in the culture of normal CMPs (Figure 6C). Sizes of day-7 myeloblast colonies were comparable with control GM colonies (not shown). Thus, PU.1 supports myelomonocytic maturation even after cells have committed to the GM lineage but appears not to be required for proliferation or survival of GM progenitors in the presence of cytokines.

Disruption of PU.1 in committed lymphoid progenitors (CLPs) did not block B-cell maturation

We tested the effect of PU.1 disruption after the completion of lymphoid commitment. Purified PU.1F/F CLPs were retrovirally transduced with the Cre gene and were cultured on an OP9 stromal layer. The PU.1 allele flanked by loxP sites became undetectable in PU.1F/F CLPs after completion of the Cre gene transduction (data not shown). In both PU.1Δ/Δ and PU.1F/F CLPs, limiting dilution assay showed that almost 1 in 15 cells read-out B-cell differentiation in the presence of IL-7 (data not shown), while colony growth was not detected in the absence of IL-7. Both PU.1Δ/Δ and PU.1F/F CLPs gave rise to CD19+IgM+ B cells on day 12 in the presence of IL-7 (Figure 7A). PU.1Δ/Δ B cells did not have detectable levels of the loxP-flanked PU.1 allele (Figure 7B). The sizes of PU.1Δ/Δ B-cell colonies were almost equal to those of PU.1F/F B cells (Figure 7C), and PU.1Δ/Δ B cells normally rearranged the D-J region of the IgH gene (Figure 7D). Figure 7E shows the PCR analyses of PU.1Δ/Δ B cells. PU.1Δ/Δ B cells lacked the PU.1 transcript, but expressed B-lymphoid transcription factors, such as paired box gene 5 (Pax)5, early B-cell factor (EBF), and their target transcripts including λ5, VpreB, and recombination activating gene 1 (RAG-1). Reflecting the positive response to IL-7 in vitro, PU.1Δ/Δ B cells expressed IL-7Rα, and the amount of IL-7Rα transcripts of PU.1Δ/Δ B cells was almost 60% of PU.1F/F B cells in a real-time PCR assay (Figure 7E).

To evaluate the effect of PU.1 disruption on B-cell development in vivo, we crossed PU.1F/F mice with the CD19-Cre mouse strain in which the Cre gene is knocked into the CD19 locus47 in order to disrupt PU.1 specifically after the pre-B stage of B-cell maturation. As expected, PU.1F/FCD19Cre/+ mice possessed normal numbers of CD19+IgM–CD43– pre–B cells and mature CD19+ B cells in the bone marrow (not shown). In the spleen, CD19+ B cells in PU.1F/FCD19Cre/+ mice completely excised the PU.1 allele (not shown), and the majority of CD19+ PU.1Δ/Δ B cells expressed IgM and IgD (Figure 7F). We purified CD19+ PU.1Δ/Δ B cells from the spleen and tested their proliferation activity in response to a variety of mitogenic agents including anti-IgM antibodies, LPS, and PMA plus ionomycin (P+I). As shown in Figure 7F, CD19+ PU.1Δ/Δ B cells displayed significant proliferation in response to each type of stimulation. These data collectively suggest that PU.1 is not necessary for the functional B-cell maturation from CLPs.

Discussion

Transcription factors have been shown to play key roles in activation and maintenance of commitment and maturation programs in hematopoietic development.48,49 HSCs have been shown to “promiscuously” express multiple myeloid genes,5,6 including PU.1, and these transcripts at low levels have been considered to be “sterile.” In this paper, we show that PU.1 is expressed in functional HSCs at the single-cell level, and that the constitutive expression of PU.1 is necessary for maintenance of the fetal liver and the bone marrow HSC pool. PU.1 was also essential in myeloid but not B-cell maturation.

PU.1 is essential in competitive self-renewal of HSCs

It has been reported that PU.1–/– fetal liver cells could not seed the bone marrow at a detectable level,26 likely due to lack of cell migration–related integrins.31 By injecting a high dose of purified PU.1–/– fetal liver HSCs, we showed that they could home to and colonize the bone marrow at least for 3 months (Figure 2C), but PU.1–/– hematopoiesis disappeared by 6 months after transplantation. Similarly, bone marrow PU.1Δ/Δ HSCs were defective in function and could not compete efficiently with the remaining HSCs still expressing PU.1, such that within 6 to 8 weeks most of the hematopoietic function in PU.1Δ/Δ mice arose from normal HSCs. It is important to note that PU.1F/F long-term HSCs in the bone marrow likely excised PU.1 in situ at their own bone marrow niches. Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ SP cells that are considered to attach to the bone marrow niche50 activated the knock-in GFP reporter for PU.1 and expressed PU.1 mRNA (Figure 5B-C). In addition, a vast majority of Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+ HSCs expressed PU.1-GFP, and purified Lin–Sca-1+c-Kit+CD34–PU.1-GFP+ HSCs displayed long-term reconstitution at the single-cell level (Figure 5D). Thus, the constitutive expression of PU.1 might be necessary to maintain the HSC pool, and the loss of reconstitution potential in PU.1-deficient HSCs should not depend only on their impaired homing activity to bone marrow niches.

Our data show that PU.1 plays an essential role in self-renewal of HSCs (and PU.1 transcripts in HSCs5 are not sterile) and therefore does not merely represent “lineage priming.”5,6 In turn, the “myeloid priming” in HSCs may be partly due to the PU.1 expression, since PU.1 can activate a variety of myeloid gene transcripts. For example, we have reported that lysozyme M is transcribed in HSCs with long-term reconstitution potential,8 while lysozyme M itself is not required for hematopoiesis.51 Since PU.1 can activate the transcription of multiple myeloid genes including lysozyme M,52 the “sterile” expression of lysozyme M in HSCs may result simply from PU.1 expression primarily used to maintain the HSC pool. The critical mechanism for impairment of competitive self-renewal in PU.1-deficient HSCs should be clarified by future studies.

PU.1 is required for development of CMPs as well as for maturation of myelomonocytic cells

PU.1 deficiency at the level of HSCs resulted in the disappearance of CMPs and GMPs in both fetal liver and bone marrow hematopoiesis. PU.1 is required even after the completion of commitment into the GM lineage; depletion of PU.1 at the CMP/GMP stage profoundly blocked their myelomonocytic maturation. In contrast, we have found that conditional disruption of C/EBPα in HSCs eliminated only GMPs, and if disrupted at the GMP stage, C/EBPαΔ/Δ GMPs normally generated mature granulocytes and monocytes.53 It is again of interest that these 2 major myeloid transcription factors play critical roles in different stages of myeloid development. The difference of critical checkpoints of PU.1 and C/EBPα should be taken into account in analyzing the pathogenesis of AML, since loss-of-function mutations of PU.1 or C/EBPα have been found in human AML.25,54

Although PU.1 is known to activate the expression of myeloid cytokine receptors, these cytokine signals are not necessary for their development.17,55-57 PU.1–/– fetal liver cells can respond to IL-3 or G-CSF to proliferate.11,58 Consistent with this report, PU.1-deficient CMPs/GMPs expressed IL-3Rα and G-CSFR, and could proliferate in response to these cytokines, resulting in the formation of colonies consisting of Gr-1+CD11b– immature myeloid cells in vitro (Figure 6D). In addition, Gr-1+CD11b– immature myeloid cells transiently appeared in the bone marrow 3 weeks after the conditional PU.1 disruption (Figure 4A). Therefore, PU.1 is required to operate the myelomonocytic maturation program but not for cell survival or proliferation. These data suggest that PU.1 mutations in AML patients25 may contribute to leukemogenesis through inhibiting myelomonocytic maturation of leukemic cells without disturbing proliferation and survival of myeloblasts.

Recent studies have demonstrated that the loss of MegE potential could occur earlier than that of GM potential during lymphoid commitment from HSCs, suggesting the existence of an alternative pathway for MEP development directly from HSCs.59,60 Interestingly, the number of MEPs increased in PU.1-deficient mice, suggesting that MEPs can develop by passing the CMP stage. It is possible that in PU.1-deficient hematopoiesis, the pathway for MEP development from HSCs skews toward this direct route. It is also important to note that each lineage-restricted progenitor population exists as a result of commitment in the bone marrow, and therefore, these populations may not necessarily pass through each defined stage according to their hierarchy.61 For example, HSCs do not always give rise to multilineage colonies, while a significant fraction of HSCs can form simple MegE colonies that do not contain GM cells in vitro, indicating that molecular events involved in the CMP stage are not required for their MegE differentiation. The efficiency of production of MEPs could be enhanced by the absence of PU.1, since PU.1 is known to inhibit function of GATA-1,20-23 which is both a permissive and instructive factor for the MegE lineage development.40

PU.1 is necessary for development of CLPs, but not for B-cell maturation

PU.1 disruption also induced a profound decrease of CLPs in both fetal liver and bone marrow hematopoiesis. Although IL-7Rα expression was severely impaired in PU.1–/– embryos of another PU.1–/– strain,62 our data show that IL-7Rα expression was not absolutely dependent upon PU.1 because Lin– cells possessing IL-7Rα protein were present equally in PU.1-deficient fetal liver and bone marrow hematopoiesis (Figures 1,4). The expression of IL-7Rα was also normal in mice carrying hypomorphic PU.1 alleles, which reduce PU.1 expression to approximately 20% of wild-type levels.63 The loss of CLPs in PU.1-deficient hematopoiesis is compatible with the fact that not only B-but also T-cell development is significantly impaired in PU.1–/– mice, while PU.1 is required to remain suppressed during T-cell maturation.64 In contrast to GM maturation, PU.1 is not required for B-cell maturation from CLPs. PU.1Δ/Δ CLPs developed IgM-expressing B cells only in the presence of IL-7 as normal CLPs did, and frequencies of B-cell read-outs and the size of B-cell colonies in vitro were unchanged in PU.1Δ/Δ CLPs. PU.1Δ/Δ CLP-derived B cells rearranged IgH and expressed B-cell–related genes including IL-7Rα. In agreement with these data, Ye et al65 established IL-7Rα–expressing B-cell lines from PU.1–/– fetal liver of the mouse strain we used here. Thus, development of CLPs may require some function of PU.1 in addition to induction of IL-7Rα. Furthermore, the conditional disruption of PU.1 by CD19-Cre did not affect maturation of CD19+IgM+IgD+ B cells in vivo, and these PU.1-deficient B cells were able to undergo cell division in response to the cross-linking of their surface IgM, suggesting that IgM signaling was normal in PU.1-deficient B cells. These data collectively suggest that PU.1 might not be necessary for functional B-cell maturation after the CLP stage.

Hematopoietic stage-specific effects of PU.1

It is of interest that a single transcription factor, PU.1, can exert different functions at different hematopoietic stages. This should at least be dependent upon the pre-existing state of target cells. HSCs or progenitors at each stage possess different expression profiles of transcription factors,64 which may cooperate with PU.1.5 Furthermore, the expression level of PU.1 should be critical as has been reported in B versus monocytic differentiation.19 PU.1 in the myeloid pathway is increasingly up-regulated from HSCs to GMPs,4 as shown in Figure 5C. It is thus tempting to speculate that only a low level of PU.1 is required for HSC maintenance, but increasingly high levels of PU.1 may be needed for further myeloid differentiation. We have also found that mice carrying hypomorphic PU.1 alleles maintained normal numbers of HSCs but not CMPs or GMPs, and developed an aggressive, transplantable AML.61 These data collectively suggest that down-regulation of PU.1 below a certain level might be required to set the path for AML through blocking myeloid differentiation.

In summary, our data show that constitutive expression of PU.1 is necessary for self-renewal of both fetal liver and bone marrow HSCs. PU.1 is also important for development of CMPs and CLPs from HSCs as well as maturation of granulocytes and monocytes after cells commit to the myelomonocytic lineage. The fact that PU.1 disruption impaired HSC maintenance but not GMP-derived immature myeloid cell proliferation suggests that mechanisms of self-renewal and proliferation could be separable in terms of PU.1 function. B-cell maturation and proliferation, however, do not require PU.1. Thus, detailed analyses of signaling pathways downstream of PU.1 in each stage will help us to understand critical codes in programs of self-renewal, differentiation, and proliferation in hematopoietic development.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Klaus Rajewsky for providing Mx1-Cre and CD19-Cre mouse strains; members of the Akashi and Tenen laboratories for their support; Maris Handley for superb cell sorter operation; and Mary Singleton, Alison Lugay, and Izumi Noguchi for expert assistance with preparation of the paper.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 24, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-03-0860.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants DK61320 and CA78045 (K.A.) and CA72009 and CA41456 (D.G.T.).

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

Note added in proof. While this article was in press, Dakic et al66 reported using a similar but not identical conditional PU.1 knock-out model. Deletion of the PU.1 alleles in this model resulted in a block in differentiation from the HSC to CMP and CLP stages, similar to what we describe here.

References

- 1.Shivdasani RA, Orkin SH. The transcriptional control of hematopoiesis. Blood. 1996;87: 4025-4039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tenen DG, Hromas R, Licht JD, Zhang DE. Transcription factors, normal myeloid development, and leukemia. Blood. 1997;90: 489-519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Klemsz MJ, McKercher SR, Celada A, Van Beveren C, Maki RA. The macrophage and B cell-specific transcription factor PU.1 is related to the ets oncogene. Cell. 1990;61: 113-124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404: 193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miyamoto T, Iwasaki H, Reizis B, et al. Myeloid or lymphoid promiscuity as a critical step in hematopoietic lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2002;3: 137-147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hu M, Krause D, Greaves M, et al. Multilineage gene expression precedes commitment in the hemopoietic system. Gene Dev. 1997;11: 774-785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Enver T, Greaves M. Loops, lineage, and leukemia. Cell. 1998;94: 9-12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ye M, Iwasaki H, Laiosa CV, et al. Hematopoietic stem cells expressing the myeloid lysozyme gene retain long-term, multilineage repopulation potential. Immunity. 2003;19: 689-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang DE, Hetherington CJ, Meyers S, et al. CCAAT enhancer-binding protein (C/EBP) and AML1 (CBF alpha2) synergistically activate the macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor promoter. Mol Cell B. 1996;16: 1231-1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iwama A, Zhang P, Darlington GJ, McKercher SR, Maki R, Tenen DG. Use of RDA analysis of knockout mice to identify myeloid genes regulated in vivo by PU.1 and C/EBPalpha. Nucl Acid Res. 1998;26: 3034-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DeKoter RP, Walsh JC, Singh H. PU.1 regulates both cytokine-dependent proliferation and differentiation of granulocyte/macrophage progenitors. EMBO J. 1998;17: 4456-4468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DeKoter RP, Lee H-J, Singh H. PU.1 regulates expression of the interleukin-7 receptor in lymphoid progenitors. Immunity. 2002;16: 297-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Akashi K, Kondo M, von Freeden-Jeffry U, Murray R, Weissman IL. Bcl-2 rescues T lymphopoiesis in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;89: 1033-1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nishijima I, Nakahata T, Hirabayashi Y, et al. A human GM-CSF receptor expressed in transgenic mice stimulates proliferation and differentiation of hemopoietic progenitors to all lineages in response to human GM-CSF. Mol Biol Cell. 1995; 6: 497-508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang FC, Watanabe S, Tsuji K, et al. Human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) stimulates the in vitro and in vivo development but not commitment of primitive multipotential progenitors from transgenic mice expressing the human G-CSF receptor. Blood. 1998;92: 4632-4640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iwasaki-Arai J, Iwasaki H, Miyamoto T, Watanabe S, Akashi K. Enforced GM-CSF signals do not support lymphopoiesis, but instruct lymphoid to myelomonocytic lineage conversion. J Exp Med. 2003;197: 1311-1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fairbairn LJ, Cowling GJ, Reipert BM, Dexter TM. Suppression of apoptosis allows differentiation and development of a multipotent hemopoietic cell line in the absence of added growth factors. Cell. 1993;74: 823-832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nerlov C, Graf T. PU.1 induces myeloid lineage commitment in multipotent hematopoietic progenitors. Gene Dev. 1998;12: 2403-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.DeKoter RP, Singh H. Regulation of B lymphocyte and macrophage development by graded expression of PU.1. Science. 2000;288: 1439-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang P, Behre G, Pan J, et al. Negative cross-talk between hematopoietic regulators: GATA proteins repress PU.1. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96: 8705-8710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rekhtman N, Radparvar F, Evans T, Skoultchi AI. Direct interaction of hematopoietic transcription factors PU.1 and GATA-1: functional antagonism in erythroid cells. Gene Dev. 1999;13: 1398-1411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nerlov C, Querfurth E, Kulessa H, Graf T. GATA-1 interacts with the myeloid PU.1 transcription factor and represses PU.1-dependent transcription. Blood. 2000;95: 2543-2551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang P, Zhang X, Iwama A, et al. PU.1 inhibits GATA-1 function and erythroid differentiation by blocking GATA-1 DNA binding. Blood. 2000;96: 2641-2648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walsh JC, DeKoter RP, Lee HJ, et al. Cooperative and antagonistic interplay between PU.1 and GATA-2 in the specification of myeloid cell fates. Immunity. 2002;17: 665-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mueller BU, Pabst T, Osato M, et al. Heterozygous PU.1 mutations are associated with acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2002;100: 998-1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scott EW, Simon MC, Anastasi J, Singh H. Requirement of transcription factor PU.1 in the development of multiple hematopoietic lineages. Science. 1994;265: 1573-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McKercher SR, Torbett BE, Anderson KL, et al. Targeted disruption of the PU.1 gene results in multiple hematopoietic abnormalities. EMBO J. 1996;15: 5647-5658. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spain LM, Guerriero A, Kunjibettu S, Scott EW. T cell development in PU.1-deficient mice. J Immunol. 1999;163: 2681-2687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colucci F, Samson SI, DeKoter RP, Lantz O, Singh H, Di Santo JP. Differential requirement for the transcription factor PU.1 in the generation of natural killer cells versus B and T cells. Blood. 2001;97: 2625-2632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Scott EW, Fisher RC, Olson MC, Kehrli EW, Simon MC, Singh H. PU.1 functions in a cell-autonomous manner to control the differentiation of multipotential lymphoid-myeloid progenitors. Immunity. 1997;6: 437-447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fisher RC, Lovelock JD, Scott EW. A critical role for PU.1 in homing and long-term engraftment by hematopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow. Blood. 1999;94: 1283-1290. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kim HG, de Guzman CG, Swindle CS, et al. The ETS family transcription factor PU.1 is necessary for the maintenance of fetal liver hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2004;104: 3894-3900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delassus S, Titley I, Enver T. Functional and molecular analysis of hematopoietic progenitors derived from the aorta-gonad-mesonephros region of the mouse embryo. Blood. 1999;94: 1495-1503. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kuhn R, Schwenk F, Aguet M, Rajewsky K. Inducible gene targeting in mice. Science. 1995;269: 1427-1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91: 661-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mebius RE, Miyamoto T, Christensen J, et al. The fetal liver counterpart of adult common lymphoid progenitors gives rise to all lymphoid lineages, CD45+CD4+CD3-cells, as well as macrophages. J Immunol. 2001;166: 6593-6601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Traver D, Miyamoto T, Christensen J, Iwasaki-Arai J, Akashi K, Weissman IL. Fetal liver myelopoiesis occurs through distinct, prospectively isolatable progenitor subsets. Blood. 2001;98: 627-635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Back J, Dierich A, Bronn C, Kastner P, Chan S. PU.1 determines the self-renewal capacity of erythroid progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;103: 3615-3623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goodell MA, Rosenzweig M, Kim H, et al. Dye efflux studies suggest that hematopoietic stem cells expressing low or undetectable levels of CD34 antigen exist in multiple species. Nat Med. 1997;3: 1337-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Iwasaki H, Mizuno S, Wells RA, Cantor AB, Watanabe S, Akashi K. GATA-1 converts lymphoid and myelomonocytic progenitors into the megakaryocyte/erythrocyte lineages. Immunity. 2003; 19: 451-462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.ten Boekel E, Melchers F, Rolink A. The status of Ig loci rearrangements in single cells from different stages of B cell development. Int Immunol. 1995;7: 1013-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mizuno T, Rothstein TL. Cutting edge: CD40 engagement eliminates the need for Bruton's tyrosine kinase in B cell receptor signaling for NF-kappa B. J Immunol. 2003;170: 2806-2810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Higuchi M, O'Brien D, Kumaravelu P, Lenny N, Yeoh EJ, Downing JR. Expression of a conditional AML1-ETO oncogene bypasses embryonic lethality and establishes a murine model of human t(8;21) acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer Cell. 2002;1: 63-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mikkola HK, Klintman J, Yang H, et al. Haematopoietic stem cells retain long-term repopulating activity and multipotency in the absence of stem-cell leukaemia SCL/tal-1 gene. Nature. 2003;421: 547-551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Osawa M, Hanada K, Hamada H, Nakauchi H. Long-term lymphohematopoietic reconstitution by a single CD34-low/negative hematopoietic stem cell. Science. 1996;273: 242-245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsuzaki Y, Kinjo K, Mulligan RC, Okano H. Unexpectedly efficient homing capacity of purified murine hematopoietic stem cells. Immunity. 2004; 20: 87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rickert RC, Roes J, Rajewsky K. B lymphocyte-specific, Cre-mediated mutagenesis in mice. Nucl Acid Res. 1997;25: 1317-1318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Warren LA, Rothenberg EV. Regulatory coding of lymphoid lineage choice by hematopoietic transcription factors. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15: 166-175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Orkin SH. Priming the hematopoietic pump. Immunity. 2003;19: 633-634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arai F, Hirao A, Ohmura M, et al. Tie2/angiopoietin-1 signaling regulates hematopoietic stem cell quiescence in the bone marrow niche. Cell. 2004; 118: 149-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Faust N, Varas F, Kelly LM, Heck S, Graf T. Insertion of enhanced green fluorescent protein into the lysozyme gene creates mice with green fluorescent granulocytes and macrophages. Blood. 2000;96: 719-726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Faust N, Bonifer C, Sippel AE. Differential activity of the -2.7 kb chicken lysozyme enhancer in macrophages of different ontogenic origins is regulated by C/EBP and PU.1 transcription factors. DNA Cell Biol. 1999;18: 631-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang P, Iwasaki-Arai J, Iwasaki H, et al. Enhancement of hematopoietic stem cell repopulating capacity and self-renewal in the absence of the transcription factor C/EBP alpha. Immunity. 2004;21: 853-863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pabst T, Mueller BU, Zhang P, et al. Dominant-negative mutations of CEBPA, encoding CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-alpha (C/EBPalpha), in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Genet. 2001;27: 263-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dranoff G, Crawford AD, Sadelain M, et al. Involvement of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in pulmonary homeostasis. Science. 1994;264: 713-716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Semerad CL, Poursine-Laurent J, Liu F, Link DC. A role for G-CSF receptor signaling in the regulation of hematopoietic cell function but not lineage commitment or differentiation. Immunity. 1999;11: 153-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gillessen S, Mach N, Small C, Mihm M, Dranoff G. Overlapping roles for granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor and interleukin-3 in eosinophil homeostasis and contact hypersensitivity. Blood. 2001;97: 922-928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Anderson KL, Smith KA, Conners K, McKercher SR, Maki RA, Torbett BE. Myeloid development is selectively disrupted in PU.1 null mice. Blood. 1998;91: 3702-3710. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Akashi K, Traver D, Zon LI. The complex cartography of stem cell commitment. Cell. 2005;121: 160-162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Adolfsson J, Mansson R, Buza-Vidas N, et al. Identification of flt3(+) lympho-myeloid stem cells lacking erythro-megakaryocytic potential a revised road map for adult blood lineage commitment. Cell. 2005;121: 295-306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Traver D, Akashi K. Lineage commitment and developmental plasticity in early lymphoid progenitor subsets. Adv Immunol. 2004;83: 1-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Medina KL, Pongubala JM, Reddy KL, et al. Assembling a gene regulatory network for specification of the B cell fate. Dev Cell. 2004; 7: 607-617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rosenbauer F, Wagner K, Kutok JL, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia induced by graded reduction of a lineage-specific transcription factor, PU.1. Nat Genet. 2004;36: 624-630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Anderson MK, Weiss AH, Hernandez-Hoyos G, Dionne CJ, Rothenberg EV. Constitutive expression of PU.1 in fetal hematopoietic progenitors blocks T cell development at the pro-T cell stage. Immunity. 2002;16: 285-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ye M, Ermaermakova-Cirilli O, Graf T. B cell development in the absence of PU.1 [abstract]. Blood. 2004;104: 68a. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dakic A, Metcalf D, Di Rago L, Mifsud S, Wu L, Nutt SL. PU.1 regulates the commitment of adult hematopoietic progenitors and restricts granulopoiesis. J Exp Med. 2005;201: 1487-1502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.