Abstract

Here we report that a new nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mouse line harboring a complete null mutation of the common cytokine receptor γ chain (NOD/SCID/interleukin 2 receptor [IL2r] γnull) efficiently supports development of functional human hemato-lymphopoiesis. Purified human (h) CD34+ or hCD34+hCD38– cord blood (CB) cells were transplanted into NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns via a facial vein. In all recipients injected with 105 hCD34+ or 2 × 104 hCD34+hCD38– CB cells, human hematopoietic cells were reconstituted at approximately 70% of chimerisms. A high percentage of the human hematopoietic cell chimerism persisted for more than 24 weeks after transplantation, and hCD34+ bone marrow grafts of primary recipients could reconstitute hematopoiesis in secondary NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients, suggesting that this system can support self-renewal of human hematopoietic stem cells. hCD34+hCD38– CB cells differentiated into mature blood cells, including myelomonocytes, dendritic cells, erythrocytes, platelets, and lymphocytes. Differentiation into each lineage occurred via developmental intermediates such as common lymphoid progenitors and common myeloid progenitors, recapitulating the steady-state human hematopoiesis. B cells underwent normal class switching, and produced antigen-specific immunoglobulins (Igs). T cells displayed the human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–dependent cytotoxic function. Furthermore, human IgA-secreting B cells were found in the intestinal mucosa, suggesting reconstitution of human mucosal immunity. Thus, the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system might be an important experimental model to study the human hemato-lymphoid system.

Introduction

To analyze human immune and hematopoietic development and function in vivo, a number of studies have been tried to reproduce human hematopoiesis in small animal xenotransplantation models.1 Successful transplantation of human hematopoietic tissues in immune-compromised mice was first reported in late 1980s by using homozygous severe combined immunodeficient (C.B.17-SCID) mice. In the first model of a humanized lymphoid system in a SCID mouse (SCID-hu model), McCune et al simultaneously transplanted human fetal tissues, including fetal liver hematopoietic cells, thymus, and lymph nodes, into SCID mice and induced mature human T- and B-cell development.2 Mosier et al successfully reconstituted human T and B cells by transferring human blood mononuclear cells into SCID mice.3 These initial studies suggested the usefulness of immunodeficient mice for reconstitution of the human lymphoid system from human bone marrow hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs).

After these initial reports, a number of modified SCID models have been proposed to try to reconstitute human immunity.4 In addition, recombination activating gene (RAG)–deficient strains have been used as recipients in xenotransplantation: T- and B-cell–deficient Prkdcscid, Rag1–/–, or Rag2–/– mutant mice5-7 were capable of supporting engraftment of human cells. The engraftment levels in these models, however, were still low, presumably due to the remaining innate immunity of host animals.1 Nonobese diabetic/severe combined immunodeficient (NOD/SCID) mice have been shown to support higher levels of human progenitor cell engraftment than BALB/c/SCID or C.B.17/SCID mice.8 Levels of human cell engraftment were further improved by treating NOD/SCID mice with anti-asialo GM1 (ganglioside-monosialic acid) antibodies9 that can abrogate natural killer (NK) cell activity. Recently, NOD/SCID mice harboring either a null allele at the β2-microglobulin gene (NOD/SCID/β2m–/–)10 or a truncated common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc) mutant lacking its cytoplasmic region (NOD/SCID/γc–/–)11,12 were developed. In these mice, NK- as well as T- and B-cell development and functions are disrupted, because β2m is necessary for major histocompatibility complex (MHC) class I–mediated innate immunity, and because γc (originally called IL-2Rγ chain) is an indispensable component of receptor heterodimers for many lymphoid-related cytokines (ie, IL-2, IL-7, IL-9, IL-12, IL-15, and IL-21).13 Injection of human bone marrow or cord blood (CB) cells into these mice resulted in successful generation of human T and B cells. In our hands, efficiencies of CB cell engraftment represented by percentages of circulating human (h) CD45+ cells were significantly (2- to 5-fold) higher in NOD/SCID/β2m–/– newborns than those in adults (F.I., M.H., and L.D.S., unpublished data, April 2003). More recently, transplantation of hCD34+ CB cells into Rag2–/– γc–/– newborns regenerated adaptive immunity mediated by functional T and B cells,14 suggesting heightened support for xenogeneic transplants especially in the neonatal period. Efficiency of reconstitution of human hematopoiesis may be, however, still suboptimal in these models because chimerisms of human cells are not stable in each experiment.11,12,14 Furthermore, there is little information regarding reconstitution of human myeloerythroid components in these xenogeneic models.

Two types of mouse lines with truncated or complete null γc mutant15-17 have been reported. NOD/SCID/γc–/– and Rag2–/– γc–/– mouse strains harbor a truncated γc mutant lacking the intracellular domain,15 and therefore, binding of γc-related cytokines to each receptor should normally occur in these models.18 For example, IL-2R with the null γc mutations would be an αβ heterodimer complex with an affinity approximately 10 times lower than that of the high affinity αβγ heterotrimer complex in mice with the truncated γc mutant.19 γc has also been shown to dramatically increase the affinity to its ligands through the receptors for IL-4, IL-7, and IL-15.20-23 Previous studies suggested that γc-related receptors including IL-2Rβ chain and IL-4Rα chain could activate janus-activated kinases (JAKs) to some extent in the presence of the extracellular domain of γc, independent of the cytoplasmic domain of γc.24,25 Thus, in order to block the signaling through γc-related cytokine receptors more completely, we made NOD/SCID mice harboring complete null mutation of γc16 (the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull strain). By using NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns, we successfully reconstituted myeloerythroid as well as lymphoid maturation by injecting human CB or highly-enriched CB HSCs at a high efficiency. Reconstitution of human hematopoiesis persisted for a long term. The developing lymphoid cells were functional for immunoglobulin (Ig) production and human leukocyte antigen (HLA)–dependent cytotoxic activity. Our data show that the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system provides a valuable tool to reproduce human hemato-lymphoid development.

Materials and methods

Mice

NOD.Cg-PrkdcscidIL2rgtmlWjl/Sz (NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull) and NOD/LtSz-Prkdcscid/B2mnull (NOD/SCID/β2mnull) mice were developed at the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). The NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull strain was established by backcrossing a complete null mutation at γc locus16 onto the NOD.Cg-Prkdcscid strain. The establishment of this mouse line has been reported elsewhere.26 All experiments were performed according to the guideline in the Institutional Animal Committee of Kyushu University.

Cell preparation and transplantation

CB cells were obtained from Fukuoka Red Cross Blood Center (Japan). CB cells were harvested after written informed consent. Mononuclear cells were depleted of Lin+ cells using mouse anti-hCD3, anti-hCD4, anti-hCD8, anti-hCD11b, anti-hCD19, anti-hCD20, anti-hCD56, and anti–human glycophorin A (hGPA) monoclonal antibodies (BD Immunocytometry, San Jose, CA). Samples were enriched for hCD34+ cells by using anti-hCD34 microbeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Auburn, CA). These cells were further stained with anti-hCD34 and hCD38 antibodies (BD Immunocytometry), and were purified for Lin–CD34+CD38– HSCs by a FACSVantage (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, CA). Lin– hCD34+ cells (105) or 2 × 104 Lin–hCD34+hCD38– cells were transplanted into irradiated (100 cGy) NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull or NOD/SCID/β2mnull newborns via a facial vein27 within 48 hours of birth.

Examination of hematopoietic chimerism

At 3 months after transplantation, samples of peripheral blood, bone marrow, spleen, and thymus were harvested from recipient mice. Human common lymphoid progenitors were analyzed based on the expression of hCD127 (IL-7 receptor α chain) and hCD10 in Lin (hCD3, hCD4, hCD8, hCD11b, hCD19, hCD20, hCD56, and hGPA)– hCD34+hCD38+ fraction.28,29 Human myeloid progenitors were analyzed based on the expressions of hCD45RA and hCD123 (IL-3 receptor α chain) in Lin-CD10–CD34+CD38+ fractions. For the analysis of megakaryocyte/erythroid (MegE) lineages, anti-hCD41a (HIP8), anti-hGPA (GAR-2), anti-mCD41a (MW Reg30), and anti-mTer119 (Ter-119) antibodies were used. Samples were treated with ammonium chloride to eliminate mature erythrocytes, and were analyzed by setting nucleated cell scatter gates. For the analysis of circulating erythrocytes and platelets, untreated blood samples were analyzed by setting scatter gates specific for each cell fraction. Human B lymphoid progenitors were evaluated according to the criteria proposed by LeBien.30

Methylcellulose culture assay

Bone marrow cells of recipient mice were stained with anti-hCD34, hCD38, hCD45RO, hCD123, and lineage antibodies. Human HSCs, CMPs, GMPs, and MEPs were purified according to the phenotypic definition28,29 by using a FACSVantage (Becton Dickinson). One hundred cells of each population were cultured in methylcellulose media (Stem Cell Technologies, Vancouver, BC, Canada) supplemented with 10% bovine serum albumin (BSA), 20 μg/mL steel factor, 20 ng/mL IL-3, 20 ng/mL IL-11, 20 ng/mL Fms-like tyrosine kinase 3 (Flt3) ligand, 50 ng/mL granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), 4 U/ml erythropoietin (Epo), and 50 ng/mL thrombopoietin (Tpo). Colony numbers were enumerated on day 14 of culture.

Histologic analysis

Tissue samples were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and dehydrated with graded alcohol. After treatment with heated citrate buffer for antigen retrieval, paraformaldehyde-fixed paraffin-embedded sections were immunostained with mouse anti-hCD19, anti–human IgA, anti-hCD3, anti-hCD4, anti-hCD8, and anti-hCD11c antibodies (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA). Stained specimens were observed by confocal microscopy (LSM510 META microscope; Carl Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Image acquisition and data analysis were performed by using LSM5 software. Numerical aperture of the objective lens (PlanApochromat ×63) used was 1.4.

ELISA

Human Ig concentration in recipient sera was measured by using a human immunoglobulin assay kit (Bethyl, Montgomery, IL). For detection of ovalbumin (OVA)–specific human IgM and IgG antibodies, 5 recipient mice were immunized twice every 2 weeks with 100 μg of OVA (Sigma, St Louis, MO) that were emulsified in aluminum hydroxide (Sigma). Sera from OVA-treated mice were harvested 2 weeks after the second immunization. OVA was plated at s concentration of 20 μg/mL on 96-microtiter wells at 4°C overnight. After washing and blocking with bovine serum albumin, serum samples were incubated in the plate for 1 hour. Antibodies binding OVA were then measured by a standard enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Cytotoxicity of alloantigen-specific human CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell lines

Alloantigen-specific human CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell lines were established according to the method as reported.31 After stimulation with an Epstein Barr virus–transformed B lymphoblastoid cell line (TAK-LCL) established from a healthy individual (TAK-LCL) for 6 days, 100 hCD4+ T cells or hCD8+ T cells were plated with 3 × 104 TAK-LCL cells in the presence of 10 U/mL human IL-2 (Genzyme, Boston, MA), and were subjected to a chromium 51 (51Cr) release assay. A Limiting number of effector cells and 104 51Cr-labeled allogeneic target cells were incubated. KIN-LCLs that do not share HLA with effector cells or TAK-LCL were used as negative controls. Cytotoxic activity was tested in the presence or absence of anti-HLA class I or anti–HLA-DR monoclonal antibodies.

Results

Reconstitution of human hematopoiesis is achieved in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice

NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice lacked mature murine T or B cells evaluated by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS), and displayed extremely low levels of NK cell activity.31 This mouse line can survive more than 15 months31 since it does not develop thymic lymphoma, usually a fatal disease in the immune-compromised mice with NOD background.32

Lin–hCD34+ CB cells contain HSCs, and myeloid and lymphoid progenitors.28,29 We and others have reported that engraftment of human CB cells, which contain hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells, was efficient in NOD/SCID/β2m–/– and Rag2–/–/γc–/– mice, especially when cells were transplanted during the neonatal period.14,33 We therefore transplanted purified Lin–hCD34+ CB cells into sublethally irradiated NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns via a facial vein.27

We first transplanted 105 Lin–hCD34+ CB cells from 3 independent donors into 5 NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns, and found that the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system is very efficient for supporting engraftment of human hematopoietic progenitor cells. Table 1 shows percentages of hCD45+ cells in these mice 3 months after transplantation. Strikingly, the average engraftment levels were approximately 70% in both the bone marrow and the peripheral blood. Compared with 4 control NOD/SCID/β2m–/– recipient mice given transplants from the same donors, engraftment levels of hCD45+ cells in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice were significantly higher (Table 1).

Table 1.

Chimerism of human CD45+ cells in NOD/SCID/β2mnull mice and NOD/SCID/IL2rynull mice

|

% nucleated cells

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mouse no. (donor no.) | PB | BM | Spleen |

| NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull | |||

| 1 (1) | 71.2 | 70.9 | 66.8 |

| 2 (1) | 81.7 | 81.4 | 47.1 |

| 3 (2) | 50.1 | 58.8 | 49.5 |

| 4 (3) | 68.0 | 83.1 | 51.1 |

| 5 (3) | 73.3 | 70.1 | 58.1 |

| Mean ± SD | 68.9 ± 11.6* | 72.9 ± 9.8* | 54.5 ± 8.0* |

| NOD/SCID/β2mnull | |||

| 1 (1) | 10.4 | 46.1 | 22.0 |

| 2 (2) | 11.6 | 31.5 | 24.3 |

| 3 (3) | 6.9 | 18.1 | 20.7 |

| 4 (3) | 20.7 | 30.4 | 31.2 |

| Mean ± SD | 12.4 ± 5.9* | 31.5 ± 11.5* | 22.6 ± 4.7* |

To compare the engraftment levels in the two strains, 1 × 105 Lin- CD34+ cells derived from 3 CB samples were transplanted into 5 NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice and 4 NOD/SCID/β2mnull mice. At 3 months after transplantation, BM, spleen, and peripheral blood (PB) of the recipient mice were analyzed for the engraftment of human cells. Data show percentages of human CD45+ cells in each tissue.

P < .05.

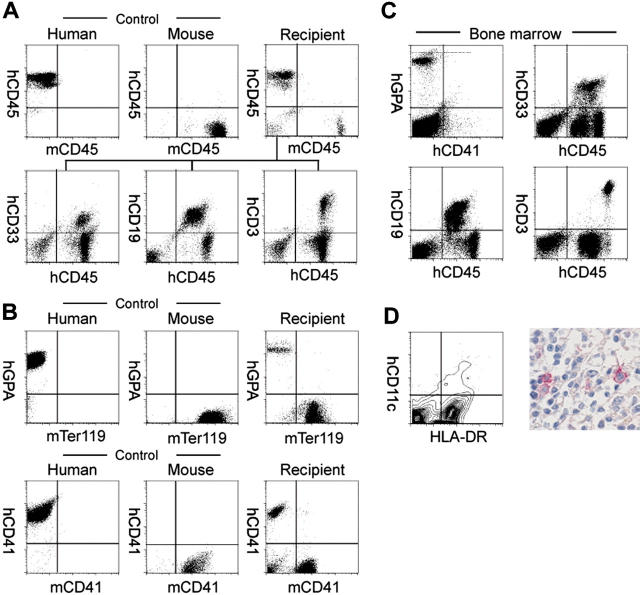

Table 2 shows the analysis of human hematopoietic cell progeny in mice that received transplants of human Lin–hCD34+ CB cells. In the peripheral blood, hCD45+ cells included hCD33+ myeloid, hCD19+ B cells, and hCD3+ T cells in all mice analyzed (Figure 1A and Table 2). We then analyzed the reconstitution of erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis in these mice. Anti–human glycophorin A (hGPA) antibodies recognized human erythrocytes, while mTer119 antibodies34 recognized GPA-associated protein on murine erythrocytes, respectively (Figure 1B). Human and murine platelets could also be stained with anti–human and anti–murine CD41a, respectively (Figure 1B). Circulating hGPA+ erythrocytes and hCD41a+ platelets were detected in all 3 mice analyzed (Figure 1B, right panels). hGPA+ erythroblasts and hCD41a+ megakaryocytes were detected as 9.5% ± 6.2% (n = 5) and 1.64% ± 0.42% (n = 5) of nucleated bone marrow cells, respectively. Thus, transplanted human Lin–hCD34+ CB cells differentiated into mature erythrocytes and platelets in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients.

Table 2.

Cellular number and composition in tissues of engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice

|

% nucleated cells (% hCD45+ cells)

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Injected cells, mice, and tissue type | Total no. cells | CD33 | CD19 | CD3 | CD11c |

| 1 × 105 Lin-CD34+ | |||||

| Mouse no. 1/ donor no. 1 | |||||

| BM | 2.4 × 107 | 8.2 (11.6) | 54.8 (77.6) | 10.7 (15.1) | 1.1 (1.6) |

| Spleen | 4.1 × 107 | 4.3 (6.4) | 33.5 (50.1) | 26.1 (39.1) | 2.2 (3.3) |

| Thymus | 3.1 × 105 | NE | 1.3 (1.3) | 96.2 (98.7) | NE |

| PB | NE | 4.0 (5.6) | 35.1 (49.3) | 19.8 (27.8) | NE |

| Mouse no. 2/donor no. 1 | |||||

| BM | 1.8 × 107 | 5.5 (6.8) | 56.5 (67.6) | 9.9 (12.2) | 2.9 (3.6) |

| Spleen | 3.2 × 107 | 2.1 (4.5) | 27.7 (58.8) | 15.9 (33.8) | 1.3 (2.8) |

| Thymus | 4.5 × 105 | NE | 1.1 (1.2) | 90.4 (98.8) | NE |

| PB | NE | 6.1 (7.5) | 53.8 (65.9) | 21.6 (40.1) | NE |

| Mouse no. 4/ donor no. 3 | |||||

| BM | 1.9 × 107 | 9.4 (11.3) | 52.9 (63.7) | 15.9 (19.1) | 0.62 (0.75) |

| Spleen | 4.4 × 107 | 3.5 (6.8) | 24.2 (47.4) | 20.8 (40.7) | 1.5 (2.9) |

| Thymus | 0.8 × 105 | NE | 0.88 (1.1) | 78.2 (98.9) | NE |

| PB | NE | 3.2 (4.7) | 61.3 (90.1) | 5.3 (7.8) | NE |

| Mouse no. 5/donor no. 3 | |||||

| BM | 2.1 × 107 | 10.2 (14.6) | 48.8 (82.0) | 9.4 (13.4) | 1.3 (1.9) |

| Spleen | 2.7 × 107 | 6.6 (11.4) | 30.4 (52.3) | 18.6 (32.0) | 1.1 (1.9) |

| Thymus | 1.1 × 105 | NE | 3.1 (3.7) | 81.1 (96.3) | NE |

| PB | NE | 9.8 (13.4) | 40.4 (55.1) | 16.8 (22.9) | NE |

| 2 × 104 Lin-CD34+CD38- | |||||

| Mouse no. 6/donor no. 4 | |||||

| BM | 2.6 × 107 | 3.1 (5.3) | 46.1 (78.7) | 8.1 (13.8) | 1.3 (2.2) |

| Spleen | 3.9v107 | 1.3 (2.7) | 40.2 (83.9) | 5.9 (12.3) | 0.54 (1.1) |

| Thymus | 1.9 × 105 | NE | 2.1 (2.3) | 89.4 (97.7) | NE |

| PB | NE | 5.4 (12.4) | 28.9 (66.3) | 9.3 (21.3) | NE |

| Mouse no. 7/donor no. 5 | |||||

| BM | 1.4 × 107 | 7.2 (14.2) | 39.6 (78.1) | 3.1 (6.1) | 0.82 (1.6) |

| Spleen | 2.2 × 107 | 2.4 (5.1) | 37.2 (79.3) | 6.8 (14.5) | 0.52 (1.1) |

| Thymus | 1.3 × 105 | NE | 0.6 (0.7) | 85.1 (99.2) | NE |

| PB | NE | 2.3 (41.7) | 49.3 (89.5) | 3.5 (6.4) | NE |

| Mouse no. 8/donor no. 6 | |||||

| BM | 1.1 × 107 | 6.1 (11.7) | 36.8 (70.6) | 7.7 (14.8) | 2.5 (4.8) |

| Spleen | 2.9 × 107 | 2.9 (4.6) | 33.8 (53.1) | 24.6 (38.6) | 2.4 (3.8) |

| Thymus | 1.9 × 105 | NE | 1.1 (1.2) | 94.1 (97.0) | NE |

| PB | NE | 8.1 (11.9) | 50.2 (73.5) | 10.0 (14.6) | NE |

BM, spleen, and thymus were harvested from engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice at 3 months after transplantation. Total cell numbers in BM and thymus represent the cells harvested from 2 femurs for BM and those harvested from a hemilobe for thymus. Recipients 1, 2, 4, and 5 received transplants of 1 × 105 Lin-CD34+ cells. Recipients 6, 7, and 8 received transplants of 2 × 104 Lin-CD34+CD38- cells. NE indicates not examined.

Figure 1.

Analysis of human hematopoietic cells in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. (A) In the scatter gates for nucleated cells, anti-hCD45 and anti-mCD45 antibodies (Abs) reacted exclusively with human and murine leukocytes, respectively. In the recipient blood, the majority of nucleated cells were human leukocytes (top row). High levels of engraftment by hCD33+ myelomonocytic cells, hCD19+ B cells, and hCD3+ T cells were achieved in peripheral blood of recipient mice given transplants of Lin–hCD34+ CB cells (bottom row). (B) Analysis of circulating erythrocytes (top row) or platelets (bottom row) in a NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipient. In the blood, Ter119+ murine erythrocytes as well as hGPA+ human erythrocytes were detected. mCD41a+ murine platelets were also reconstituted. (C) Multilineage engraftment of human cells in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull murine bone marrow. hCD33+ myelomonocytic cells, hCD19+ B cells, and hCD3+ T cells were present. hGPA+ erythroid cells and hCD41a+ megakaryocytes were also seen in the nucleated cell gate of the bone marrow. (D, left) HLA-DR+hCD11c+ dendritic cells were detected in the spleen by a flow cytometric analysis. (Right) Immunohistochemical staining of CD11c in the spleen. CD11c+ cells displayed dendritic cell morphology.

In all engrafted mice, the bone marrow and the spleen contained significant numbers of hCD11c+ dendritic cells as well as hCD33+ myeloid cells, hCD19+ B cells, and hCD3+ T cells (Table 2 and Figure 1C). hCD11c+ dendritic cells coexpressed HLA-DR that is essential for antigen presentation to T cells (Figure 1D). In contrast, in the thymus, the majority of cells were composed of hCD3+ T cells and rare hCD19+ B cells (Table 2).

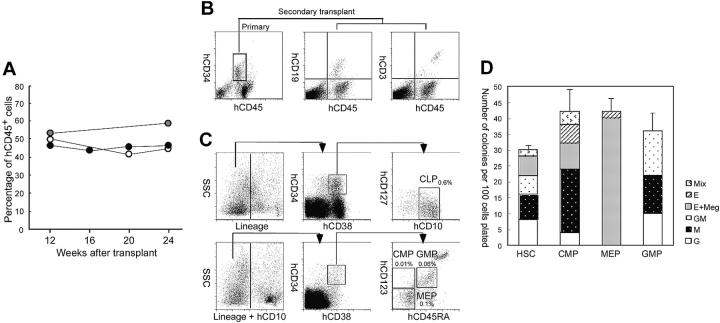

Figure 2A shows the change in the percentage of circulating hCD45+ cells in another set of NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns injected with 2 × 104 Lin–hCD34+hCD38– CB cells. Surprisingly, the level of hCD45+ cells in the blood was unchanged, and was maintained at a high level even 24 weeks after transplantation. Mice did not develop lymphoid malignancies or other complications. Furthermore, we tested the retransplantability of human HSCs in primary recipients. We killed mice at 24 weeks after the primary transplantation of hCD34+ cells, purified 1 to 5 × 104 hCD34+ cells from primary recipient bone marrow cells, and retransplanted them into NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns. In all 3 experiments, secondary recipients successfully reconstituted human hematopoiesis at least until 12 weeks after transplantation, when we killed mice for the bone marrow analysis (Figure 2B). Thus, the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system can support human hematopoiesis for the long term.

Figure 2.

Purified Lin–hCD34+hCD38– CB cells reconstitute hematopoiesis via physiological intermediates, and display long-term reconstitution in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system. (A) Serial evaluation of chimerism of human cells in peripheral blood of recipient mice injected with 2 × 104 Lin–hCD34+hCD38– CB cells. White, gray, and black dots represent 3 individual recipients. (B) hCD34+ cells purified from a primary recipient marrow (left) were successfully engrafted into the secondary newborn recipients. hCD19+ B cells (middle) and hCD3+ T cells (right) in a representative secondary recipient is shown. (C) The Lin– bone marrow cells contained hCD34+hCD38+hCD10+hCD127 (IL-7Rα)+ CLPs (top row). In the Lin–hCD10–fraction, hCD34+hCD38+hCD45RA–hCD123 (IL-3Rα)lo CMPs, hCD34+hCD38+hCD45RA+hCD123lo GMPs, hCD34+hCD38+hCD45RA–hCD123– MEPs were present. Each number for progenitors indicates percentages of hCD45+ cells. SSC indicates side scatter. (D) Colony-forming activity of purified myeloid progenitor population in the methylcellulose assay. Representative data from 1 of 3 recipients are shown. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Human cord blood hematopoietic stem cells produced myeloid and lymphoid cells via developmental intermediates in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull bone marrow

The Lin–hCD34+ CB fraction contains early myeloid and lymphoid progenitors as well as HSCs.28 To verify that differentiation into all hematopoietic cells can be initiated from human HSCs in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system, we transplanted Lin–hCD34+hCD38-CB cells that contain the counterpart population of murine long-term HSCs,35 and are highly enriched for human HSCs.36,37 hCD34+ CB cells (15%-20%) were hCD38– (data not shown). Mice given transplants of 2 × 104 Lin–hCD34+hCD38– cells displayed successful reconstitution of similar proportion of human cells compared with mice reconstituted with 1 × 105 Lin–hCD34+ cells at 12 weeks after transplantation (Table 2). In another experiment, mice injected with 2 × 104 Lin–hCD34+hCD38– cells exhibited the high chimerism (> 50%) of circulating human blood cells even 24 weeks after transplantation (not shown), suggesting the long-term engraftment of self-renewing human HSCs.

In all mice injected with Lin–hCD34+hCD38– cells, hGPA+ erythroid cells and hCD41a+ megakaryocytes were present (not shown). We then tested whether differentiation of Lin–hCD34+hCD38– HSCs in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mouse microenvironment can recapitulate normal developmental processes in the human bone marrow. We and others have reported that phenotypically separable myeloid and lymphoid progenitors are present in the steady-state normal bone marrow in both mice38,39 and humans.28,29 Figure 2C shows the representative FACS analysis data of recipient's bone marrow cells. In all 3 mice tested, the bone marrow contained the hCD34+hCD38– HSC36,37 and the hCD34+hCD38+ progenitor fractions.28 The hCD34+hCD38+hCD10+hCD127 (IL-7Rα)+ common lymphoid progenitor (CLP) population29 was detected (Figure 2C, top panels). According to the phenotypic definition of human myeloid progenitors,28 the hCD34+hCD38+ progenitor fraction was subfractionated into hCD45RA–hCD123 (IL-3Rα)lo common myeloid progenitor (CMP), hCD45RA–hCD123– megakaryocyte/erythrocyte progenitor (MEP), and hCD45RA+hCD123lo granulocyte/monocyte progenitor (GMP) populations (Figure 2C, bottom panels). We then purified these myeloid progenitors, and tested their differentiation potential. As shown in Figure 2D, purified GMPs and MEPs generated granulocyte/monocyte (GM)– and megakaryocyte/erythrocyte (MegE)–related colonies, respectively, while CMPs as well as HSCs generated mixed colonies in addition to GM and MegE colonies. These data strongly suggest that hCD34+hCD38– human HSCs differentiate into all myeloid and lymphoid lineages tracking normal developmental steps of the steady-state human hematopoiesis within the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mouse bone marrow.

Development of human systemic and mucosal immune systems in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice

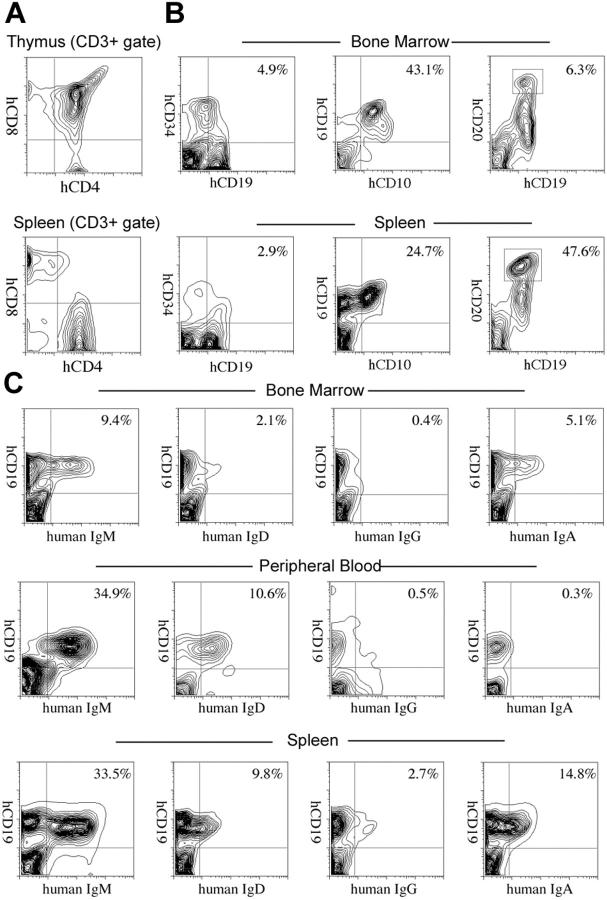

We further evaluated development of the human immune system in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. In the thymus, thymocytes were mostly consisted of hCD3+ T cells with scattered hCD19+ B cells (Figure 3A-B). This is reasonable since the normal murine thymus contain a small number of B cells in addition to T cells.40 Thymocytes consisted of immature hCD4+hCD8+ double-positive (DP) T cells (Figure 3C) as well as small numbers of hCD4+ or hCD8+ single-positive (SP) mature T cells (Figure 4A, top panel), while hCD3+ human T cells in spleen were mainly constituted of either hCD4+ or hCD8+ single positive T cells (Figure 4A, bottom panel). These data suggest that normal selection processes of T-cell development may occur in the recipients' thymi.

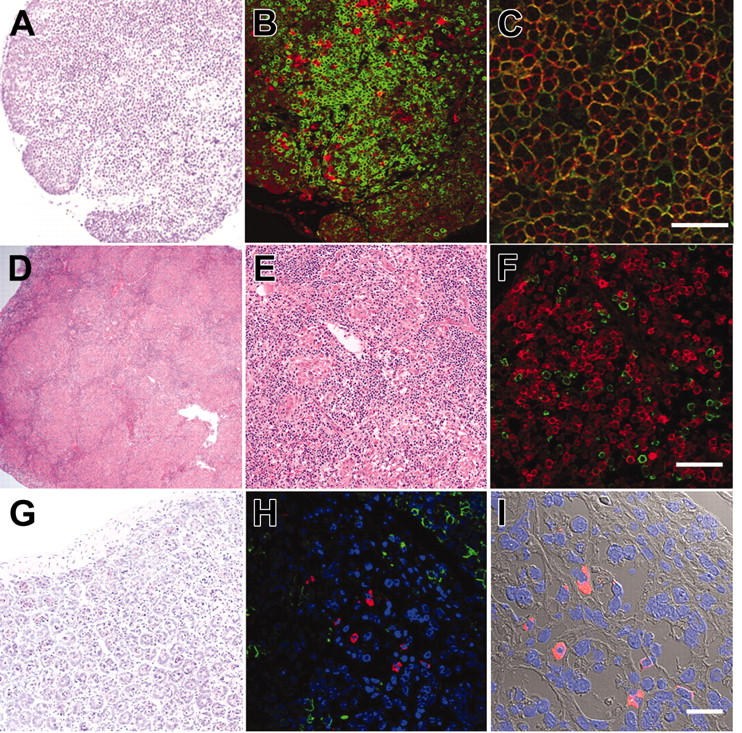

Figure 3.

Histology of lymphoid organs in engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. (A) The thymus showed an increased cellularity after reconstitution. (B) The thymus stained with anti-hCD3 (green) and anti-hCD19 (red) antibodies. (C) The thymus stained with anti-hCD4 (green) and anti-hCD8 (red) antibodies. The majority of thymocytes are doubly positive for hCD4 and hCD8. (D-E) Lymphoid follicle-like structures in the spleen of a recipient. (F) The lymphoid follicles mainly contained hCD19+ B cells (red) that were surrounded by scattered hCD3+ T cells (green). (G) Histology of the intestine in an engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipient (left). (H) In the intestine, DAPI+ (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole)–nucleated cells (blue) contained both scattered hCD3+ T cells (green) and human IgA+ cells (red). (I) The DIC image of the same section shows that IgA+ B cells were mainly found in the interstitial region of the intestinal mucosal layer. White bars inside panels represent 80 μm (C), 100μm (F), and 20μm (I).

Figure 4.

Development of lymphocytes in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. (A) The flow cytometric analysis of human T cells in recipients. The majority of cells in the thymus were hCD4+hCD8+ double-positive thymocytes (top). The CD3+ spleen cells contained hCD4+ or hCD8+ single-positive mature T cells (bottom). (B) hCD34+hCD19+ pro-B, hCD10+hCD19+ pre-B, and hCD19+hCD20hi mature B cells were seen in different proportions in the bone marrow and the spleen of recipient mice. Numbers represent percentages within total nucleated cells. (C) B cells expressing each class of human immunoglobulin heavy chain were seen in the bone marrow, the peripheral blood (PB), or the spleen of engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice. Numbers represent percentages out of nucleated cells.

In the spleen, lymphoid follicle-like structures were seen (Figure 3D-E), where predominant hCD19+ B cells were associated with surrounding scattered hCD3+ T cells (Figure 3F). Development of mesenteric lymph nodes was also observed, where the similar follicle-like structures consisted of human B and T cells were present (not shown). In the bone marrow and the spleen, nucleated cells in each organ contained hCD34+hCD19+ pro-B cells, hCD10+hCD19+ immature B cells, and hCD19+hCD20+ mature B cells (Figure 4B). Figure 4C shows the expression of human immunoglobulins on hCD19+ B cells. A significant fraction of hCD19+ B cells expressed human IgM on their surface. A fraction of cells expressing IgD were also observed in the blood and the spleen, suggesting that class switching occurred in these developing B cells. As reported in the Rag2–/– γc–/– mouse models,10,12,14 hCD19+IgA+ B cells were detected in the bone marrow and the spleen in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. We then evaluated concentrations of human immunoglobulins in sera of mice given transplants of human Lin–hCD34+ CB cells by ELISA. In all sera from 3 NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients, a significant amount of IgG (257 ± 76 μg/mL) and IgM (600 ± 197 μg/mL) were detectable, whereas sera from the control NOD/SCID/β2m–/– mice contained lower levels of IgM (76 ± 41 μg/mL) and little or no IgG (Table S1, available on the Blood website; see the Supplemental Table link at the top of the online article). These data collectively suggest that class-switching can effectively occur in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice.

The intestinal tract is one of the major sites for supporting host defense against exogenous antigens. Since bone marrow and spleen hCD19+ B cells contained a significant fraction of cells expressing IgA, we tested whether reconstitution of mucosal immunity could be achieved in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. Immunohistologic analyses demonstrated that the intestinal tract of recipient mice contained significant numbers of cells expressing human IgA in addition to hCD3+ T cells (Figure 3G-I). Thus, human CB cells could reconstitute cells responsible for both systemic and mucosal immunity in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system.

Function of adaptive human immunity in engrafted NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice

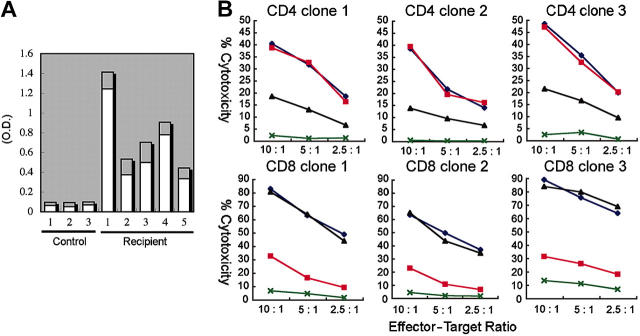

Five NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice reconstituted with 3 independent human CB samples were immunized twice with ovalbumin (OVA) at 3 months after transplantation. Two weeks after immunization, sera were collected from these immunized mice, and were subjected to ELISA to quantify OVA-specific human IgG and IgM. As shown in Figure 5A, significant levels of OVA-specific human IgM and IgG were detected in all serum samples from immunized mice, but not in samples from nonimmunized engrafted mice. Thus, the adaptive human immune system properly functioned in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull strain to produce antigen-specific human IgM and IgG antibodies.

Figure 5.

Functional analysis of human T and B cells developed in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. (A) Production of OVA-specific human immunogloblins. Two weeks after immunization with OVA, sera of 5 independent recipients were sampled, and were evaluated for the concentration of OVA-specific human IgM (□) and IgG ( ) by ELISA. Sera of 3 nonimmunized NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients were used as controls. O.D. indicates optical density. (B) Cytotoxic activity of human T cells generated in NOD/SCID/IL2rg-null mice. hCD4+ and hCD8+ T-cell clones derived from the recipient spleen were cocultured with allogeneic target cells (TAK-LCLs). KIN-LCLs that do not share any HLA type with effector cells or TAK-LCLs (X) were used as negative controls. Both hCD4+ and hCD8+ T-cell lines displayed cytotoxic activity against TAK-LCL in a dose-dependent manner. In hCD4+ T-cell clones, this effect was blocked by anti–HLA-DR antibodies (▴), whereas in hCD8+ T-cell clones, the effect was blocked by anti–HLA class I antibodies (▪). ♦ indicates cytotoxic response to TAK-LCLs without addition of antibodies.

) by ELISA. Sera of 3 nonimmunized NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients were used as controls. O.D. indicates optical density. (B) Cytotoxic activity of human T cells generated in NOD/SCID/IL2rg-null mice. hCD4+ and hCD8+ T-cell clones derived from the recipient spleen were cocultured with allogeneic target cells (TAK-LCLs). KIN-LCLs that do not share any HLA type with effector cells or TAK-LCLs (X) were used as negative controls. Both hCD4+ and hCD8+ T-cell lines displayed cytotoxic activity against TAK-LCL in a dose-dependent manner. In hCD4+ T-cell clones, this effect was blocked by anti–HLA-DR antibodies (▴), whereas in hCD8+ T-cell clones, the effect was blocked by anti–HLA class I antibodies (▪). ♦ indicates cytotoxic response to TAK-LCLs without addition of antibodies.

We next tested the alloantigen-specific cytotoxic function of human T cells developed in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. hCD3+ T cells isolated from the spleen of NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients were cultured with allogeneic B-LCL (TAK-LCL). We established 8 hCD4+ and 10 hCD8+ T-cell clones responding LCL-specific allogeneic antigens. We then estimated cytotoxic activity of these T-cell clones in the presence or absence of anti–HLA-DR and anti–HLA class I antibodies. We randomly chose 3 each of CD4 and CD8 clones for further analysis (Figure 5B). A 51Cr release assay revealed that both hCD4+ and hCD8+ T cell clones exhibited cytotoxic activity against allogeneic TAK-LCL, whereas they showed no cytotoxicity against KIN-LCL, a cell line not sharing HLA classes I or II with TAK-LCL. Cytotoxic activity of hCD4+ and hCD8+ T cell clones was significantly inhibited by the addition of anti–HLA-DR and anti–HLA class I antibodies, respectively. These data clearly demonstrate that human CB-derived T cells can exhibit cytotoxic activity in an HLA-restricted manner.

Discussion

Xenogeneic transplantation models have been extensively used to study human hematopoiesis in vivo.1,41,42 In the present study, we describe a new xenogeneic transplantation system that effectively supports human hemato-lymphoid development of all lineages for the long term.

NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns exhibited very efficient reconstitution of human hematopoietic and immune systems after intravenous injection of a relatively small number of CB cells. In our hands, NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns displayed a significantly higher chimerism of human blood cells compared with NOD/SCID/β2m–/– newborns under an identical transplantation setting (Table 1). This result directly shows that the IL2rγnull mutation has a merit on human cell engraftment over the β2m–/– mutation.

One of the critical problems in the NOD/SCID strain for the use of recipients is that this mouse line possesses a predisposition to thymic lymphoma due to an endogenous ectropic provirus (Emv-30).32 Because of this, NOD/SCID and NOD/SCID/β2m–/– mice have the short mean lifespan of 8.5 and 6 months, respectively, while NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice did not develop thymic lymphoma surviving more than 15 months,31 which allows a long-term experimentation.

In our study, NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborns injected with 105 hCD34+ CB cells via a facial vein consistently displayed high levels of chimerism of human hematopoiesis (50%-80%; Table 1). This model is comparable to, or may be more efficient than the Rag2–/– γc–/– newborn model where intrahepatic injection of 0.4 to 1.2 × 105 hCD34+ CB cells generated variable levels of chimerism of human cells (5%-65%).14 This slight difference of engraftment efficiency, however, could reflect the homing efficiency of HSCs by each injection route. The NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn model might be more efficient than the NOD/SCID/γc–/– adult model in which the majority of recipients showed approximately 30% chimerism of human cells after transplantation of 5 × 104 hCD34+ CB cells.11 Although we did not test NOD/SCID/γc–/– newborns side by side in this study, we have found that the engraftment level of hCD34+ cells of human acute myelogenous leukemia is approximately 3-fold higher in newborns than adults in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull strain (F.I., T.M., S.Y., M.Y., M.H., K.A., and L.D.S., manuscript in preparation). Therefore, it remains unclear whether the IL2rγnull mutation has a significant advantage over the truncated γc mutation11 for human cell engraftment. It is still possible that the improved engraftment efficiencies in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system as compared to those in the NOD/SCID/γc–/– adult system reflect the age-dependent maturation of the xenogeneic barrier.

The Rag2–/– γc–/– newborn and NOD/SCID/γc–/– adult models have provided definitive evidences that functional T cells, B cells, and dendritic cells can develop from hematopoietic progenitor cells in immunodeficient mice. Class-switching of immunoglobulin in CB-derived B cells properly occurred in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull but not in the NOD/SCID/β2m–/– newborns (Table S1), further confirming the advantage of the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull model. We also showed that, consistent with a previous report using the Rag2–/– γc–/– model,14 human T and B cells developed in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull mice are capable of mounting antigen-specific immune responses. Interestingly, human T and B cells migrated into murine lymphoid organs and into the intestinal tissues to collaborate in forming lymphoid organ structures. Furthermore, we found that IgA-secreting human B cells can develop in the murine intestine, suggesting that human mucosal immunity could be generated. Thus, the cellular interaction and the lymphocyte homing could occur at least to some extent across the xenogenic barrier in this model. It is also of interest that developing human cells in the thymus displayed normal distribution of SP and DP cells (Figure 4A), and that mature human T cells displayed cytotoxic functions in an HLA-dependent manner (Figure 5B). This suggests that positive and/or negative selection of human T cells could occur in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. Thymic epithelial cells in recipients reacted with anti-murine but not anti-human centromere probes in a FISH assay (F.I. and M.H., unpublished data, September 2004), confirming their recipient's origin. Thus, it remains unclear how these human T cells effectively educated and developed in murine thymus. It is also possible that human mature T cells developed by extrathymic education and selection.

Our data directly show that the most primitive hCD34+hCD38– CB cells are capable of generating the human myeloerythroid system in addition to the immune system in the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. The emergence of circulating hCD33+ myelomonocytic cells after transplantation of human CB cells has been reported in the NOD/SCID/β2m–/– newborn33 and the NOD/SCID/γc–/– adult11 systems. Development of human erythropoiesis, however, has not been obtained in previous models, although it has been reported that NOD/SCID mice can support terminal maturation of hCD71+ erythroblasts that were induced ex vivo from human HSCs by culturing with human cytokines.43 We showed for the first time that human erythropoiesis and thrombopoiesis can develop in mice from primitive hCD34+hCD38– cells, as evidenced by the presence of erythroblasts and megakaryocytes in the bone marrow and of circulating erythrocytes and platelets in NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull recipients. It is important to note that the hCD34+hCD38– CB HSC population generated myeloid- and lymphoid-restricted progenitor populations such as CMPs, GMPs, MEPs, and CLPs in the bone marrow (Figure 2E-F). Thus, the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull microenvironment might be able to support physiological steps of myelopoiesis and lymphopoiesis initiating from the primitive HSC stage.

In summary, we show that the NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system efficiently supports hemato-lymphoid development from primitive human HSCs, passing through physiological developmental intermediates. It also can support development of human systemic and mucosal immunity, and therefore may be useful to use human immunity to produce immunoglobulins or experimental vaccines. The NOD/SCID/IL2rγnull newborn system might also serve as an efficient tool for understanding malignant hematopoiesis in humans, since the analysis of human leukemogenesis has mainly been dependent upon the NOD/SCID adult mouse system.44-46 Our model might also be useful to reproduce the transforming process of human hematopoietic cells, as transplanted murine hematopoietic progenitor and stem cells can develop leukemia by transducing oncogenic fusion genes in syngeneic mouse models.47,48 Thus, the use of this system should open a more efficient way to analyze normal and malignant human hematopoiesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Bruce Gott and Lisa Burzenski for excellent technical assistance, and Dr Sato and other staff at Fukuoka Cord Blood Bank for preparation of CB.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, May 26, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-02-0516.

Supported by grants from Japan Society for Promotion of Science (F.I.); the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (M.Y.); the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare of Japan (M.H.); and National Institutes of Health grants A130389 and HL077642 (L.D.S.) and DK061320 (K.A.).

The online version of the article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

- 1.Greiner DL, Hesselton RA, Shultz LD. SCID mouse models of human stem cell engraftment. Stem Cells. 1998;16: 166-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCune JM, Namikawa R, Kaneshima H, Shultz LD, Lieberman M, Weissman IL. The SCID-hu mouse: murine model for the analysis of human hematolymphoid differentiation and function. Science. 1988;241: 1632-1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mosier DE, Gulizia RJ, Baird SM, Wilson DB. Transfer of a functional human immune system to mice with severe combined immunodeficiency. Nature. 1988;335: 256-259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaneshima H, Namikawa R, McCune JM. Human hematolymphoid cells in SCID mice. Curr Opin Immunol. 1994;6: 327-333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pflumio F, Izac B, Katz A, Shultz LD, Vainchenker W, Coulombel L. Phenotype and function of human hematopoietic cells engrafting immune-deficient CB17-severe combined immunodeficiency mice and nonobese diabetic-severe combined immunodeficiency mice after transplantation of human cord blood mononuclear cells. Blood. 1996;88: 3731-3740. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shultz LD, Lang PA, Christianson SW, et al. NOD/LtSz-Rag1null mice: an immunodeficient and radioresistant model for engraftment of human hematolymphoid cells, HIV infection, and adoptive transfer of NOD mouse diabetogenic T cells. J Immunol. 2000;164: 2496-2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldman JP, Blundell MP, Lopes L, Kinnon C, Di Santo JP, Thrasher AJ. Enhanced human cell engraftment in mice deficient in RAG2 and the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Br J Haematol. 1998;103: 335-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Greiner DL, Shultz LD, Yates J, et al. Improved engraftment of human spleen cells in NOD/LtSz-scid/scid mice as compared with C.B-17-scid/scid mice. Am J Pathol. 1995;146: 888-902. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yoshino H, Ueda T, Kawahata M, et al. Natural killer cell depletion by anti-asialo GM1 antiserum treatment enhances human hematopoietic stem cell engraftment in NOD/Shi-scid mice. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26: 1211-1216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kollet O, Peled A, Byk T, et al. beta2 microglobulin-deficient (B2m(null)) NOD/SCID mice are excellent recipients for studying human stem cell function. Blood. 2000;95: 3102-3105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ito M, Hiramatsu H, Kobayashi K, et al. NOD/SCID/gamma(c)(null) mouse: an excellent recipient mouse model for engraftment of human cells. Blood. 2002;100: 3175-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hiramatsu H, Nishikomori R, Heike T, et al. Complete reconstitution of human lymphocytes from cord blood CD34+ cells using the NOD/SCID/gammacnull mice model. Blood. 2003;102: 873-880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leonard WJ. Cytokines and immunodeficiency diseases. Nat Rev Immunol. 2001;1: 200-208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Traggiai E, Chicha L, Mazzucchelli L, et al. Development of a human adaptive immune system in cord blood cell-transplanted mice. Science. 2004; 304: 104-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohbo K, Suda T, Hashiyama M, et al. Modulation of hematopoiesis in mice with a truncated mutant of the interleukin-2 receptor gamma chain. Blood. 1996;87: 956-967. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cao X, Shores EW, Hu-Li J, et al. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor gamma chain. Immunity. 1995;2: 223-238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DiSanto JP, Muller W, Guy-Grand D, Fischer A, Rajewsky K. Lymphoid development in mice with a targeted deletion of the interleukin 2 receptor gamma chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995; 92: 377-381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Asao H, Takeshita T, Ishii N, Kumaki S, Nakamura M, Sugamura K. Reconstitution of functional interleukin 2 receptor complexes on fibroblastoid cells: involvement of the cytoplasmic domain of the gamma chain in two distinct signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90: 4127-4131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takeshita T, Asao H, Ohtani K, et al. Cloning of the gamma chain of the human IL-2 receptor. Science. 1992;257: 379-382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell SM, Keegan AD, Harada N, et al. Inter-leukin-2 receptor gamma chain: a functional component of the interleukin-4 receptor. Science. 1993;262: 1880-1883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Noguchi M, Nakamura Y, Russell SM, et al. Inter-leukin-2 receptor gamma chain: a functional component of the interleukin-7 receptor. Science. 1993;262: 1877-1880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kondo M, Takeshita T, Higuchi M, et al. Functional participation of the IL-2 receptor gamma chain in IL-7 receptor complexes. Science. 1994; 263: 1453-1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kondo M, Takeshita T, Ishii N, et al. Sharing of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor gamma chain between receptors for IL-2 and IL-4. Science. 1993; 262: 1874-1877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ferrag F, Pezet A, Chiarenza A, et al. Homodimerization of IL-2 receptor beta chain is necessary and sufficient to activate Jak2 and down-stream signaling pathways. FEBS Lett. 1998;421: 32-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Reichel M, Nelson BH, Greenberg PD, Rothman PB. The IL-4 receptor alpha-chain cytoplasmic domain is sufficient for activation of JAK-1 and STAT6 and the induction of IL-4-specific gene expression. J Immunol. 1997;158: 5860-5867. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shultz LD, Lyons BL, Burzenski LM, et al. Human lymphoid and myeloid cell development in NOD/LtSz-scid IL2rgnull mice engrafted with mobilized human hematopoietic stem cells. J Immunol. 2005;174: 6477-6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sands MS, Barker JE, Vogler C, et al. Treatment of murine mucopolysaccharidosis type VII by syngeneic bone marrow transplantation in neonates. Lab Invest. 1993;68: 676-686. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Manz MG, Miyamoto T, Akashi K, Weissman IL. Prospective isolation of human clonogenic common myeloid progenitors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99: 11872-11877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galy A, Travis M, Cen D, Chen B. Human T, B, natural killer, and dendritic cells arise from a common bone marrow progenitor cell subset. Immunity. 1995;3: 459-473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.LeBien TW. Fates of human B-cell precursors. Blood. 2000;96: 9-23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanai F, Ishii E, Kojima K, et al. Essential roles of perforin in antigen-specific cytotoxicity mediated by human CD4+ T lymphocytes: analysis using the combination of hereditary perforin-deficient effector cells and Fas-deficient target cells. J Immunol. 2003;170: 2205-2213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Prochazka M, Gaskins HR, Shultz LD, Leiter EH. The nonobese diabetic scid mouse: model for spontaneous thymomagenesis associated with immunodeficiency. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89: 3290-3294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishikawa F, Livingston AG, Wingard JR, Nishikawa S, Ogawa M. An assay for long-term engrafting human hematopoietic cells based on newborn NOD/SCID/beta2-microglobulin(null) mice. Exp Hematol. 2002;30: 488-494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kina T, Ikuta K, Takayama E, et al. The monoclonal antibody TER-119 recognizes a molecule associated with glycophorin A and specifically marks the late stages of murine erythroid lineage. Br J Haematol. 2000;109: 280-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okuno Y, Iwasaki H, Huettner CS, et al. Differential regulation of the human and murine CD34 genes in hematopoietic stem cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99: 6246-6251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Craig W, Kay R, Cutler RL, Lansdorp PM. Expression of Thy-1 on human hematopoietic progenitor cells. J Exp Med. Vol. 177; 1993: 1331-1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Terstappen LW, Huang S, Safford M, Lansdorp PM, Loken MR. Sequential generations of hematopoietic colonies derived from single nonlineage-committed CD34+CD38-progenitor cells. Blood. 1991;77: 1218-1227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Akashi K, Traver D, Miyamoto T, Weissman IL. A clonogenic common myeloid progenitor that gives rise to all myeloid lineages. Nature. 2000;404: 193-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kondo M, Weissman IL, Akashi K. Identification of clonogenic common lymphoid progenitors in mouse bone marrow. Cell. 1997;91: 661-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Akashi K, Richie LI, Miyamoto T, Carr WH, Weissman IL. B lymphopoiesis in the thymus. J Immunol. 2000;164: 5221-5226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zanjani ED. The human sheep xenograft model for the study of the in vivo potential of human HSC and in utero gene transfer. Stem Cells. 2000;18: 151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Stier S, Cheng T, Forkert R, et al. Ex vivo targeting of p21Cip1/Waf1 permits relative expansion of human hematopoietic stem cells. Blood. 2003; 102: 1260-1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Neildez-Nguyen TM, Wajcman H, Marden MC, et al. Human erythroid cells produced ex vivo at large scale differentiate into red blood cells in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20: 467-472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lumkul R, Gorin NC, Malehorn MT, et al. Human AML cells in NOD/SCID mice: engraftment potential and gene expression. Leukemia. 2002;16: 1818-1826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hope KJ, Jin L, Dick JE. Acute myeloid leukemia originates from a hierarchy of leukemic stem cell classes that differ in self-renewal capacity. Nat Immunol. 2004;5: 738-743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bonnet D, Dick JE. Human acute myeloid leukemia is organized as a hierarchy that originates from a primitive hematopoietic cell. Nat Med. 1997;3: 730-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cozzio A, Passegue E, Ayton PM, Karsunky H, Cleary ML, Weissman IL. Similar MLL-associated leukemias arising from self-renewing stem cells and short-lived myeloid progenitors. Genes Dev. 2003;17: 3029-3035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Huntly BJ, Shigematsu H, Deguchi K, et al. MOZ-TIF2, but not BCR-ABL, confers properties of leukemic stem cells to committed murine hematopoietic progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2004; 6: 587-596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.