Abstract

Disease relapse is a barrier to achieving therapeutic success after unrelated umbilical cord-blood transplantation (UCBT) for B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL). While adoptive transfer of donor-derived tumor-specific T cells is a conceptually attractive approach to eliminating residual disease after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, adoptive immunotherapy after UCBT is constrained by the difficulty of generating antigen-specific T cells from functionally naive umbilical cord-blood (UCB)–derived T cells. Therefore, to generate T cells that recognize B-ALL, we have developed a chimeric immunoreceptor to redirect the specificity of T cells for CD19, a B-lineage antigen, and expressed this transgene in UCB-derived T cells. An ex vivo process, which is compliant with current good manufacturing practice for T-cell trials, has been developed to genetically modify and numerically expand UCB-derived T cells into CD19-specific effector cells. These are capable of CD19-restricted cytokine production and cytolysis in vitro, as well as mediating regression of CD19+ tumor and being selectively eliminated in vivo. Moreover, time-lapse microscopy of the genetically modified T-cell clones revealed an ability to lyse CD19+ tumor cells specifically and repetitively. These data provide the rationale for infusing UCB-derived CD19-specific T cells after UCBT to reduce the incidence of CD19+ B-ALL relapse.

Introduction

Banked unrelated umbilical cord blood (UCB) is source of hematopoietic stem cells for patients with B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).1 However, despite maximally intensive preparative regimens, disease-relapse remains a significant cause of mortality after umbilical cord-blood transplantation (UCBT).

Adoptive therapy after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) with ex vivo–expanded donor-derived tumor-specific T cells might be used to augment the graft-versus-leukemia (GVL)–effect, thereby reducing the incidence of leukemic relapse, without exacerbating graft-versus-host disease (GVHD).2,3 While the feasibility of isolating, expanding, and infusing antigen-specific αβ T-cell receptor (TCR)+ T cells from peripheral blood (PB) has been validated in animals and humans,4-10 the naive function of neonatal T cells precludes a priori identification of resident tumor-specific T cells. Redirecting the specificity of T cells through enforced expression of antigen-specific immunoreceptors and differentiating UCB-derived T cells into cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) is one approach to overcoming this lack of endogenous tumor-specific T cells specific for desired targets.11,12 We and others are developing adoptive immunotherapy platforms using single-chain chimeric immunoreceptors to redirect the specificity of primary human T cells and NK cells for cell-surface proteins expressed on tumor targets, such as the B-lineage–specific antigen CD19, a molecule expressed on normal and neoplastic B cells.13-22 These chimeric immunoreceptors typically fuse extracellular single-chain antibodies to the intracellular domain of the CD3-ζ chain or FcR-γ chain and are distinguished by an ability both to bind antigen and to transduce T-cell activation signals.23 These immunoreceptors are “universal,” as they bind antigen in an HLA-independent fashion; thus, one receptor construct can be used to treat a population of patients with antigen-positive tumors.

To determine whether genetic introduction of a single-chain chimeric immunoreceptor successfully overcomes the naivety and immaturity of UCB-derived T cells, we generated T cells from UCB that expresses a CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor designated CD19R.

Materials and methods

Expression plasmid vectors

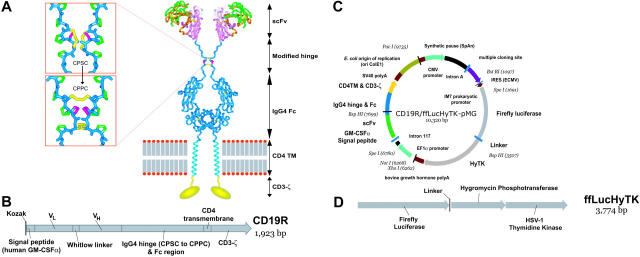

The plasmid CD19R/HyTK-pMG has been described previously.17 The plasmid HyTK-pMG,24 which expresses the bifunctional fusion gene of hygromycin phosphotransferase and HSV-1 thymidine kinase (HyTk),25 was modified to express a trifunctional fusion gene composed of North American firefly (Photinus pyralis) luciferase (ffLuc) fused to HyTK (ffLucHyTK). The ffLucHyTK transgene was cloned into HyTK-pMG to create the plasmid ffLucHyTK-pMG. The chimeric receptor gene CD19R was inserted to create the plasmid CD19R/ffLucHyTK-pMG (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematics of CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor and DNA plasmid coexpressing CD19R and trifunctional reporter gene. (A) Ribbon-model of the CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor (CD19R) shown dimerized on the cell surface. CD19R is composed of murine scFv (coupled using the Whitlow linker71), a modified serine → proline (CPSC changed to CPPC,72 single-letter amino acid code) human Fc region, human CD4 transmembrane (TM) region, and human CD3-ζ domain. Coloring: pink = VH; green = VL; orange = CDR loops; white = Whitlow linker (GSTSGSGKPGSGEGSTKG); dark blue = hinge/Fc; light blue = transmembrane helix; yellow = CD3-ζ chain (schematic); red/gray = lipid bilayer (schematic); yellow sticks = disulfides; magenta = second proline in CPPC sequence. Boxes show stick models of CPSC to CPPC amino acid change in the modified IgG4 hinge region. Computer modeling demonstrates that substitution of serine with proline at position 241 (Kabat numbering system)73 in the IgG4 hinge region creates a molecule predisposed to interchain disulfide bridging, whereas the native hinge is predisposed to intrachain disulfide bond formation. In the top panel the flexible serine in the sequence CPSC allows intrachain disulfides to form, thus preventing covalent bonding of heavy chain pairs. In the bottom panel the rigid proline in CPPC prevents the cysteines in the mutant IgG4 hinge from forming intrachain bonds, thus favoring covalent bonding of heavy chain pairs. Coloring: dark blue = backbone atoms; green = proline side chains; magenta = serine wild-type (top panel) or proline mutation (bottom panel); yellow = disulfide-bonded cysteines. (B) Schematic of fusion gene of CD19R showing component parts. (C) Schematic of DNA plasmid CD19R/ffLucHyTK-pMG to expresses CD19R gene under control of human elongation factor (EF) 1α promoter and ffLucHyTK gene under control of the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) major immediate early promoter. This plasmid is similar to the clinical vector CD19R/HyTK-pMG, with the exception in the clinical vector the IRES element was deleted, intron A was reduced, and a 20-base pair sequence was deleted 5′ to the IM7 prokaryotic promoter. Selected restriction enzyme sites are shown. (D) Schematic of fusion gene composed of firefly luciferase linked via amino acid (linker = QLISGANGV) to hygromycin phosphotransferase and thymidine kinase (predicted molecular weight of ∼137 kDa).

Nonviral gene transfer

Nucleated cells (5 × 107) were obtained from anticoagulated umbilical cord blood by density-gradient centrifugation over Ficoll-Paque-Plus (Pharmacia Biotech, Piscataway, NJ) and stimulated on day 0 with 30 ng/mL OKT3 (Ortho Biotech, Raritan, NJ). rhIL-2 at 25 U/mL was added on the following day. On day 3 the cells were genetically modified by electroporation with Pac I–linearized CD19R/HyTK-pMG or CD19R/ffLucHyTK-pMG using previously described methods.17,21 Beginning 2 days after electroporation, hygromycin B (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was added to cultures at a cytocidal concentration of 0.2 mg/mL active drug. Daudi26 lymphoma cells were genetically modified to express the ffLuc gene by electroporating with the plasmid ffLucZeo-pcDNA, as previously described, and propagated in a cytocidal concentration (0.2 mg/mL) of zeocin (InvivoGen, San Diego, CA).21 U251T were genetically modified to express the truncated CD19 (tCD19)27 gene by lipofectamine transfection with the DNA plasmid pCI-rCD19-neo (kindly provided by Dr Michio Kawano, Yamaguchi University School of Medicine, Japan), propagated in a cytocidal concentration (0.25 mg/mL) of G418 (Calbiochem, San Diego, CA) and sorted for high expression of CD19.21 8 × 106 MHC class I–/II– CD19–K56228,29 erythroleukemia cells were genetically modified by electroporation in hypo-osmolar buffer with plasmid tCD19/ffLucHyTK-pMG to express tCD19. On day 3 after transfection, the cells were selected in cytocidal concentration (0.4 mg/mL, active drug) of hygromycin B, sorted for high expression of tCD19, and cloned.

Propagation of cell lines and UCB-derived T cells

Lymphoblastoid cells (LCLs), CD19+ Daudi, and CD19–K562 cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 (Irvine Scientific, Santa Ana, CA) supplemented with 2 mM L-glutamine (Irvine Scientific), 25 mM HEPES (Irvine Scientific), 100 U/mL penicillin, 0.1 mg/mL streptomycin (Irvine Scientific), and 10% heat-inactivated defined fetal calf serum (FCS) (Hyclone, Logan, UT), referred to as culture media (CM). U251T human glioblastoma cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (Irvine Scientific) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS and antibiotics as described for CM. UCB was obtained after informed consent (in accordance with the Helsinki protocol) after severing of the umbilical cord or from the discarded tubing set after completion of UCBT. A modification of the Riddell et al method30 was used to propagate the genetically modified UCB-derived T cells. Two-week stimulation/expansion cultures were established using 106 T-cells, 30 ng/mL OKT3, 5 × 107 (fresh) or 108 (frozen) γ-irradiated (3500 cGy) peripheral-blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs), obtained from healthy volunteer donors under informed consent, and γ-irradiated (8000 cGy) LCLs at a final 5:1 PBMC/LCL ratio in CM. rhIL-2 was added to culture at 25 U/mL every 48 hours, beginning on day 1 of each 14-day expansion cycle. Hygromycin B at 0.2 mg/mL was added on day 5 of subsequent stimulation cycles. For large-scale expansions, cells from multiple flasks were pooled and transferred to a LifeCell bag (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). Beginning 14 days after electroporation, some T-cell bulk cultures were cloned by limiting dilution. Genetic modification and expansion of CD19-specific T cells from adult PB was described previously.17

In vitro ganciclovir-mediated T-cell ablation

On day 0, 0.5 × 106 UCB-derived T cells were stimulated with γ-irradiated 50 × 106 PBMCs and 107 LCLs in 25 mL CM supplemented with 30 ng/mL OKT3. Two millileters of cell suspension was plated per well (4 × 104 T cells/well) in 5 μM GCV (Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ). Then, 25 U/mL of rhIL-2 was added beginning on day 1 and repeated every 48 hours. Total and viable cells (trypan blue exclusion) were counted after 14 days.

Western blot

Expression of the chimeric 66-kDa CD3-ζ was accomplished using a mouse anti–human CD3-ζ mAb (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) under reducing and nonreducing conditions, based on methods previously described.17

Flow cytometry

The following fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), and PE-Cy5 (CyChrome)–conjugated reagents were obtained from BD Biosciences: anti-TCRαβ, anti-CD2, anti-CD3ε, anti-CD4, anti-CD8α, anti-CD11a, anti-CD18, anti-CD19, anti-CD25, anti-CD26, anti-CD27, anti-CD28, anti-CD45RA, anti-CD45RO, anti-CD49a, anti-CD50, anti-CD54, anti-CD58, anti-CD69, anti-CD70, anti-CD80, anti-CD122 (IL2-Rβ), anti-CD132 (IL-2Rγ), anti-CD95L (FasL), anti-CD95 (Fas), anti–HLA DR, antiperforin, and anti–granzyme A. PE-conjugated anti-NKG2D (clone 149810), anti-CCR7, and anti–IL-7Rα were from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). F(ab')2 fragment of FITC-conjugated goat anti–human Fcγ (catalog number 109-096-008, Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) was used at 1/20 dilution to detect cell-surface expression of CD19R. Purified goat antibody (Jackson Immunoresearch) was used as a nonspecific control. In some experiments, CyChrome-conjugated mAbs were replaced with 1 μg/mL propidium iodide (PI) to exclude nonviable cells from analyses. Intracellular staining was performed on fixed and permeabilized cells per manufacturer's instructions (Cytofix/Cytoperm and Perm/Wash solutions, BD Biosciences). Data acquisition was on a FACS Calibur (BD Biosciences) analyzed using CellQuest version 3.3 (BD Biosciences). Fluorescent activated cell sorting was performed using a MoFlo MLS (Dako-Cytomation, Fort Collins, CO).

Cytokine assay

CD8+ UCB-derived responder T cells (106) were cocultured at a 1:1 ratio in 12-well tissue culture plates with γ-irradiated (8000 cGy) CD19– (parental) U251T or tCD19+ U251T stimulator cells in CM. After 12 hours at 37°C, the conditioned media was assayed by cytometric bead array (CBA) per manufacturer's instructions (BD Biosciences) on a FACS Calibur.

Chromium release assay

The cytolytic activity of T cells was determined by 4-hour chromium release assay (CRA) as previously reported using effector to target (E/T) cell ratios of 50:1, 25:1, 5:1, and 1:1.17,21 Data are reported as mean ± the standard deviation (SD).

Video time-lapse microscopy

Imaging was undertaken at 37°C on 4 identically equipped Eclipse TS100 microscopes with Plan Fluar 4 ×/0.13 numeric aperture PhL DL phase contrast objective lenses (Nikon, Melville, NY) coupled to Sanyo video CCD cameras (Sanyo, Chatsworth, CA), digitized at 640 × 480 pixels with a Matrox frame grabber board (Matrox, Quebec, Canada). 0.2 × 106 T cells in 200 μL Hanks balanced salt solution, supplemented with 0.1% human serum albumin, were added to T-25 flasks containing adherent parental U251T or tCD19+ transfected U251T cell lines, plated 4 hours prior to assay at 0.5 × 106 cells/flask. U251T cells were chosen as targets based on an ability to identify living, dividing, and dying/dead cells by phase contrast dynamic morphology. Adherent U251T cells are spread, except during division when they round up, become figure eights, and divide. Dying cells round up and implode. Acquisition rate was at 4 frames per minute. MetaMorph version 6.31 (Molecular Devices/Universal Imaging, Downing-town, PA) was used to mark events as T-cell engaging or disengaging from a tumor cell, tumor-cell death, and tumor-cell division. We quantified on/kill/off/divide events from the first approximately 900 frames after inspecting all 4799 frames.

Luciferase activity

ffLuc transgene bioluminescence activity was measured from 105 cells with 0.14 mg/mL D-luciferin (Xenogen, Alameda, CA) using a Victor2 Luminometer (PerkinElmer, Boston, MA).

Animal tumor model

Six days prior to experimentation, 10- to 14-week-old female NOD/Scid (nonobese diabetic, severe combined immunodeficient, NOD/LtSz-PrkdcScid/J) mice (Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were γ-irradiated to 2.5 Gy using a 137Cs-source (JL Shepherd Mark I Irradiator, San Fernando, CA) and maintained under pathogen-free conditions at the City of Hope Animal Resources Center. On day –5, the NOD/Scid mice were injected in the peritoneum with 106 ffLuc+ CD19+ Daudi cells. Beginning on day –4, tumor engraftment was evaluated by bioluminescent imaging (BLI). Mice with progressively growing tumors were segregated into 2 treatment groups. One group received 3 doses, in 3-day intervals, of a 50 × 106 UCB-derived CD8+ CD19-specific T-cell clone by intraperitoneal injection. The other group received no T cells. Both groups received rhIL-2 (25 000 U/mouse) every other day by intraperitoneal injection, beginning the day of T-cell injection. Animal experiments were in compliance with protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

In vivo ganciclovir-mediated T-cell ablation

On day –7, NOD/Scid mice were sublethally γ-irradiated (2.5 Gy). On day 0, 107 γ-irradiated (80 Gy) Daudi cells were injected into the peritoneal cavity. Three hours later, the mice received by intraperitoneal injection 107 cells of an UCB-derived CD8+CD19R+ffLuc+HyTK+ T-cell bulk line. That same day, the T cells were imaged, and the mice were segregated into 2 treatment groups so that the average T-cell–derived ffLuc activity was approximately the same between the groups. Beginning on the day of adoptive transfer of T cells, one group of mice received 0.125 mg in 200 μL by intraperitoneal injection of GCV (diluted in PBS) twice a day for 8 days. The other group received intraperitoneal injections of 200 μL PBS in a parallel schedule. All mice received rhIL-2 (25 000 U/mouse) on days 0 (after T-cell injection), 2, 5, 7, and 9 by intraperitoneal injection. T-cell persistence was evaluated by serial biophotonic imaging (see next paragraph). Animal experiments were in compliance with protocols approved by the institutional animal care and use committee.

Bioluminescent imaging of T cells and tumor cells

The in vivo luciferase activity was noninvasively detected in NOD/Scid mice using an intensified CCD camera (biophotonics), based on previously published methods.21 In brief, up to 6 anesthetized mice were simultaneously imaged. One unmanipulated mouse in each imaging group was injected D-luciferin to determine the background bioluminescence. The tumor-derived and T-cell–derived ffLuc-activity was measured using an IVIS 100 series system (Xenogen), beginning approximately 15 minutes after intraperitoneal injection of 150 μL (4.29 mg/mouse) D-luciferin potassium salt (Xenogen). Photons were quantified using Living Image version 2.20 (Xenogen), and the bioluminescence signal was measured as total photon flux normalized for exposure time and surface area and expressed in units of photons/second/cm2/steradian (p/s/cm2/sr). For anatomic localization, a pseudocolor image representing light intensity (blue, least intense; red, most intense) was superimposed over a digital grayscale body surface reference image. WinMorph (www.DebugMode.com) version 3.01 morphing software and Adobe (San Jose, CA) Premiere Pro version 7.0 was used to convert 2 sets of 4 images into a cinematic sequence.

Results

Genetic modification of UCB-derived T cells with CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor

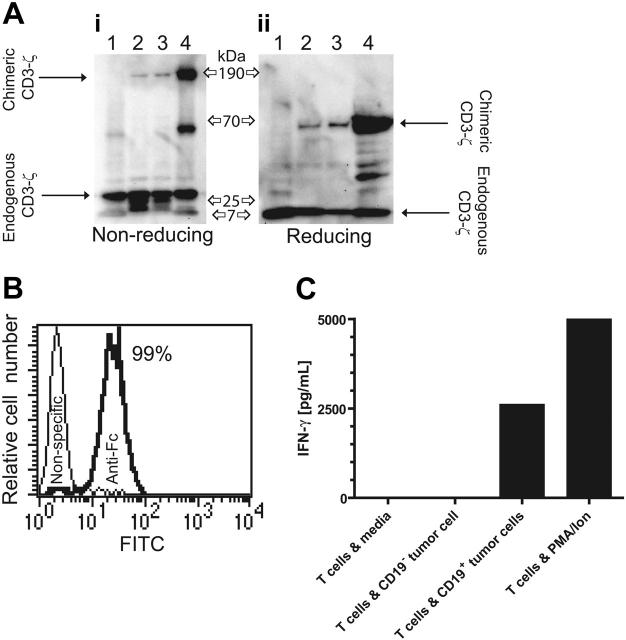

UCB-derived T cells were genetically modified with a nonviral gene transfer system to express the CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor (Figure 1A,B) and propagated using a reiterative 14-day numeric expansion process, which can be readily adapted to manufacture T cells in compliance with cGMP for phase 1/2 adoptive immunotherapy trials. The genetically modified UCB-derived T cells expanded on cytocidal concentrations of hygromycin B express CD19R transgene by Western blot analysis, as revealed by an approximately 66-kDa chimeric CD3-ζ protein under reducing conditions (Figure 2A) and by flow cytometry analysis using antibody specific for human Fc (Figure 2B). Western blot analysis under nonreducing conditions reveals an approximately 190-kDa chimeric CD3-ζ protein, which is consistent with oligomerization of CD19R (based on the predicted molecular weight of 69 kDa), favored by the CPSC → CPPC amino acid substitution within the IgG4 hinge-region of the CD19R transgene (Figure 1A).

Figure 2.

Expression of CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor in UCB-derived T cells leads to CD19-dependent cytokine production. (A) Western blot of lysates of lane 1 unmodified Jurkat cells, lanes 2 and 3 two UCB-derived T-cell clones genetically modified with the plasmids CD19R/ffLucHyTK-pMG and CD19R/HyTK-pMG, respectively, and lane 4 CD19R+ Jurkat cell under nonreducing (i) and reducing (ii) conditions and stained with mAb specific for CD3-ζ. (B) Flow cytometry staining of UCB-derived CD8+ genetically modified T-cell clone with goat-derived polyclonal FITC-conjugated Fc-specific antibody (bold line) and nonspecific control antibody. (C) CD19-specific activation of genetically modified UCB-derived T cells for IFN-γ cytokine production. As a positive control, UCB-derived T cells were stimulated in CM with PMA (10 ng/mL) and ionomycin (1 μM). Background cytokine production was determined from T cells incubated in CM. IFN-γ was measured by CBA after 12 hours of culture.

The redirected functional activity of the ex vivo–expanded genetically modified UCB-derived T cells was determined by examining whether CD19R+ T cells could produce a Tc1-type cytokine in response to CD19 stimulation. The CD19-specific T cells were incubated with CD19+ tumor cells and, after 12 hours, the conditioned media was analyzed for cytokine content. It was determined that UCB-derived CD19R+ T cells specifically released approximately 700-fold more IFN-γ in response to tumor cells bearing CD19 antigen, compared with these same T cells incubated with tumor cells that do not express CD19 (Figure 2C). No significant difference in the pattern of cytokine expression was detected when T cells and stimulator cells were incubated for up to 48 hours (data not shown). We did not detect secretion of IL-2 in response to CD19+ stimulator cells (data not shown), which is consistent with a differentiated state of the ex vivo–propagated CD8+ CD28neg T cells stimulated with OKT3 and rhIL-2 (Figure 3) and delivery of an activation signal solely through chimeric CD3-ζ.

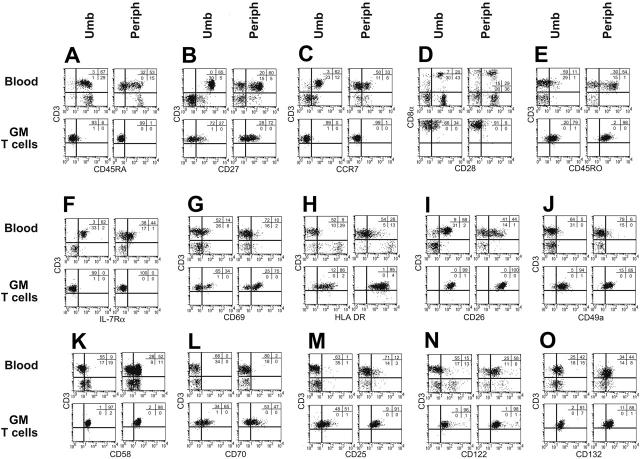

Figure 3.

Cell-surface phenotype of UCB-derived and PB-derived T cells before and after genetic modification. Multiparameter flow cytometry was performed on mononuclear cells from peripheral (periph) and cord blood (Umb) and genetically modified (GM) T cells that had been propagated for an average of 10 weeks under cytocidal concentrations of hygromycin B. Isotype-matched fluorescent mAb was used to establish the negative gates. The percentage of cells in each quadrant is shown.

Genetically modified and ex vivo–propagated T cells derived from UCB and PB express similar cell-surface molecules

Freshly isolated CD3+ UCB-derived T cells expressed a naive immunophenotype31-33 characterized by expression of CD45RA (96%), CD27 (100%), and CCR7 (95%) (Figure 3A-C), whereas T cells directly isolated from adult PB expressed a heterogeneous pattern of staining of these markers. This finding reflects the fact that PB contains a mixture of naive, memory, and effector T-cell subpopulations and is consistent with the observation that the proportion of CD45RO+ memory cells in PB increases with age.34 Our ex vivo genetic modification and propagation of both UCB- and PB-derived T cells resulted in differentiation toward a CD8+ effector-memory phenotype characterized by up-regulation of CD45RO expression and concurrent down-regulation of expression of CD45RA, CD27, CCR7, CD28, and CD127 (Figure 3A-F) and induction of activation markers CD69, HLA DR, and CD26 (Figure 3G-I). In addition, we observed an increase in the expression of T-cell adhesion/immunomodulatory molecules CD49a35 (VLA-1), CD58, and CD70 (Figure 3J-L). The ex vivo activation and propagation of UCB- and PB-derived genetically modified T cells is dependent in part on the addition of exogenous rhIL-2 and, as expected, the cell-surface expression of the 3 component chains of the T-cell high-affinity IL-2 receptor (IL-2Rα, IL2-Rβ, IL-2Rγ) increased during the period of ex vivo cell culture for both UCB- and PB-derived T cells. Thus, the overall pattern of these flow cytometry determinants is similar on genetically modified ex vivo–propagated T cells derived from both UCB and adult PB.

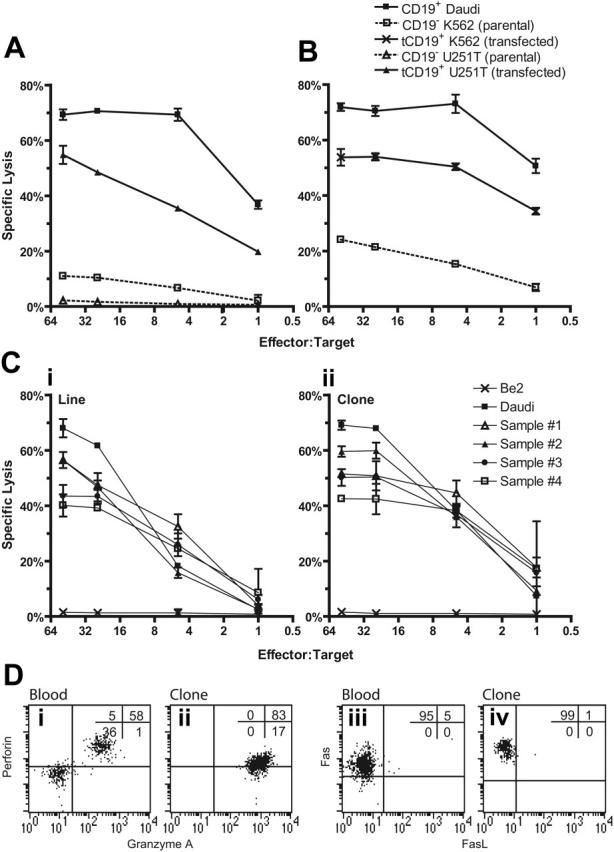

Genetically modified UCB-derived T cells exhibit redirected killing of CD19+ tumor targets

The decreased incidence of severe GVHD after pediatric UCBT may be due to a reduction in the magnitude of the cytotoxic alloresponse in neonatal T cells,36-39 and this reduction may compromise the ability of genetically modified UCB-derived T cells to kill tumor targets. Therefore, we determined whether UCB-derived T cells expressing the CD19R transgene could specifically lyse CD19+ tumor targets. Four-hour CRAs demonstrated that both bulk and cloned populations of the genetically modified UCB-derived T cells specifically lysed tumor targets expressing CD19 with approximately 70% of CD19+ tumor cells lysed at an E/T cell ratio of 50:1 (Figure 4). Specificity for CD19 is indicated by the lysis of CD19+ U251T cells but not parental CD19neg U251T cells (Figure 4A). To determine whether target-cell lysis was due to recognition of allelic HLA variants by endogenous αβ TCR, we expressed tCD19 in K562 cells, which do not express classic HLA class I or II molecules. The genetically modified UCB-derived T-cell line and clone exhibited 5-fold (at E/T of 1:1) greater lysis of CD19+ K562 compared with CD19neg K562 cells, which is consistent with activation of the T cells for cytolysis through introduced chimeric immunoreceptor and not via the endogenous αβ TCR (Figure 4B). 51Cr-released from CD19–K562 is most likely due to NK T-cell activity inherent in the genetically modified T cells, since K562 cells are susceptible to NK-mediated lysis. We evaluated whether CD19-specific UCB-derived T cells could lyse primary B-ALL cells (Figure 4C). Four primary B-ALL samples were loaded with 51Cr and between 40% and 60% of the blasts were lysed at E/T cell ratio of 50:1. The killing of B-ALL blasts was more efficient using a CD8+ T-cell clone compared with the T-cell line, reflecting a higher percentage of cells with cell-surface expression of the CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor on the clone relative to the bulk population (data not shown).

Figure 4.

CD19-specific lysis of tumor targets by genetically modified UCB-derived T cells. (A) Killing of tumor CD19+ target cells (HLA Ineg Daudi and genetically modified U251T) by CD8+ CD19R+ T-cell clone in 4-hour CRA. Background lysis of CD19– (parental K562 and U251T) cells is shown. (B) Killing of HLA class I/II– K562 cells transfected to express CD19 by CD8+ T-cell clone. (C) Killing of 4 primary B-ALL samples by UCB-derived genetically modified CD19-specific T-cell line (i) and T-cell clone (ii). (Flow cytometry on the B-ALL samples established that the lymphoid-gated cells were 68% to 83% CD19+CD10+ (versus 96% for Daudi cells) and 92% to 98% CD19+ (versus 100%), while the total population was 44% to 72% CD19+CD10+ (versus 91%) and 70% to 94% CD19+ (versus 99%). Background lysis of CD19–BE2 neuroblastoma cells is shown. CRA results of mean ± SD specific lysis of triplicate wells at E/T cell ratios of 50:1 to 1:1 are shown. (D) Intracellular multiparameter flow cytometry evaluating intracellular perforin and granzyme A expression, gating on CD8α+ lymphocytes, and cell-surface expression of Fas and FasL, gating on CD3+ lymphocytes, obtained from cryopreserved unmanipulated UCB (i and iii) and genetically modified UCB-derived T-cell clone (ii and iv). Crosshairs were established using isotype-matched nonspecific control mAbs.

The T-cell effector-mechanism for the CD19-specific lysis of target cells occurs through granule exocytosis and death-ligand–dependent mechanisms. Flow cytometry was used to determine whether critical proteins of both cytolytic pathways were expressed in genetically modified UCB-derived T cells (Figure 4D). Lymphocytes (containing a mixture of NK and T cells) from unmanipulated UCB and UCB-derived genetically modified T cells could both be demonstrated to be perforin+ and granzyme A+, but the propagated cells had a relatively decreased expression of perforin. UCB-derived genetically modified T cells expressed Fas, but only very low amounts of membrane-bound Fas ligand (FasL) and tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (data not shown). While genetically modified T cells derived from PB are also Fas+ and mostly FasL–, the level of expression of Fas in UCB- and PB-derived genetically modified T cells was similar, whereas lymphocytes from unmanipulated PB, as previously reported,40 had higher expression of Fas compared with unmanipulated lymphocytes from UCB (data not shown). Based on these flow cytometry data, we surmise that the CD19-specific cytolytic activity of UCB-derived T cells appears to be mediated predominately through the perforin/granzyme lytic pathway.

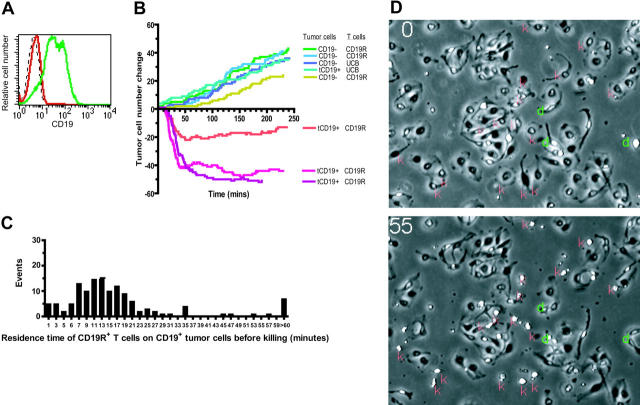

Visualizing CD19-specific killing of CD19+ tumor by genetically modified UCB-derived T cells

Video time-lapse microscopy (VTLM) allows direct inspection of CD8+CD19R+ UCB-derived T cells killing CD19+ tumor cells and determination of whether T cells can recycle their killing ability. The video microscopy reveals the engagement and disengagement of T cells (small, white, retractile bodies) to adherent spindle-shaped parental U251T tumor cells and U251T genetically modified to express CD19 (Figure 5A). The viability of the tumor cells during the assay can be evaluated by observing their ability to divide, compared to tumor cells undergoing T-cell–mediated destruction that leads to their rounding up and death. We observed that 20% of the CD19+ tumor cells are killed by CD19R+ UCB-derived T cells, compared with no killing of CD19neg tumor cells or CD19+ tumor cells cocultured with CD19Rneg T cells (data not shown). When killing data are plotted over time, we demonstrate a net loss of CD19+ tumor cells cocultured with CD19R+ T cells, compared with a net gain of tumor cells in controls, reflecting the ongoing cell division of tumor cells in the control wells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

Video time-lapse microscopy to evaluate tumor-cell killing by UCB-derived T cells. (A) Relative binding of human CD19-specific mAb by flow cytometry expression of truncated CD19 on parental U251T (red) and transfected U251T (green), compared with isotype-matched mAb binding to transfected U251T (dashed black line). The CD19 expression of transfected cells was 87% as measured by Overton analysis (FCS Express Version 2; De Novo Software, Ontario, Canada). These tumor cells were used in the VTLM studies described for panel B. (B) Net change in number of adherent tumor cells over time (240 minutes, 960 frames) cocultured with UCB-derived T cells. Tumor-cell divisions were observed in all experimental conditions (CD19R± T cells cocultured with CD19± tumor cells). Killing of tumor cells, represented by a net decrement in the number of tumor cells (below the x-axis), was only observed in flasks of CD19R+ T cells cocultured with CD19+ tumor cells. The data were compiled from 3 video time-lapse sequences acquired with the combination of CD8+ CD19R+ T-cell clone and CD19+ tumor cells, and 5 video time-lapse sequences were acquired of negative controls (parental CD19– tumor cells and CD8+ UCB derived T-cell clone that did (CD19R+) and did not (CD19R–) express the chimeric immunoreceptor). (C) Histogram of residence time (minutes) of CD8+ CD19-specific T-cell clone on CD19+ tumor cell before a CD19+ U251T tumor-killing event was recorded. Two-minute bins were used, and 145 T-cell contact events were evaluated. (D) VTLM of UCB-derived CD19R+ T cells cocultured with CD19+ tumor cells. Two images are shown (at 0 and 55 minutes). Red “k” indicates killing event, green “d” indicates cell division. Online material includes a movie (Video S1) of the VTLM (at 1 × and 2 × magnification) showing the coculture of CD19-specific T cells with CD19+ tumor cells over 120 minutes (part I) and first 60 minutes (part II).

T cells transiently scan the surface of dendritic cells for cognate antigen presented by HLA-restricted molecules using an antigen-independent adhesion mechanism with maximal cell-cell conjugation occurring approximately 20 minutes after the initial incubation of T cells with dendritic cells (DCs).41,42 Based on 3 coculture videos, we determined that the mean residence time a UCB-derived CD19-specific T cell spent on a CD19+ tumor cell before that tumor cell was killed was approximately 22 ± 26 (mean ± SD) minutes, with a median of 15 minutes (Figure 5C). This was similar to the residence time the CD19R– T cells spent on CD19+ tumor targets (data not shown). A small number (approximately 3%) of the CD19-dependent killing events occurred soon after (< 2 minutes) a T cell contacted a CD19+ tumor cell, 90% of the tumor killing took place in less than 36 minutes, and 5% of the killing occurred after more than 60 minutes of sustained contact (Figure 5C).

Antibody molecules have a higher functional affinity for antigen compared with the binding of αβ T-cell receptor (TCR) to peptide in the context of MHC. Thus, the use of an scFv to direct the specificity of UCB-derived T cells for CD19 raises the possibility that CD19-specific T cells may not be able to recycle their cytolytic activity. However, the pattern of T-cell lytic activity demonstrated by VTLM reveals that between 45% to 67% of the CD19+ tumor cells were killed by CD19-specific T cells that had previously killed other CD19+ targets (Table 1). T cells that were capable of repetitive killing represented 20% to 30% of the observed T cells. VTLM data that capture these events are shown in Figures 5D and S1, and in Video S1 (see the Supplemental Materials link at the top of the online article, at the Blood website).

Table 1.

CD8+CD19R+ UCB-derived T-cell clone's repetitive killing of CD19+ tumor cells

|

Replicate 1

|

Replicate 2

|

Replicate 3

|

Totals

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of kills per T cell | No. of T cells | No. of tumor kills | No. of T cells | No. of tumor kills | No.of T cells | No. of tumor kills | No. of T cells | No. of tumor kills |

| 0 | 8 | 0 | 17 | 0 | 16 | 0 | 41 | 0 |

| 1 | 11 | 11 | 35 | 35 | 24 | 24 | 70 | 70 |

| 2 | 5 | 10 | 10 | 20 | 17 | 34 | 32 | 64 |

| 3 | 4 | 12 | 3 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 27 |

| Totals | 28 | 33 | 65 | 64 | 59 | 64 | 152 | 161 |

CD19-specific T cells from UCB can treat established CD19+ tumor in vivo

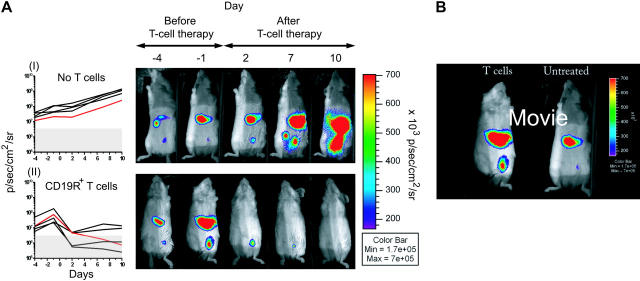

We evaluated the ability of UCB-derived CD19-specific T cells to control the growth of established CD19+ tumor in NOD/Scid mice (Figure 6). To noninvasively quantify tumor burden before and after adoptive immunotherapy, CD19+ Daudi cells were genetically modified to constitutively express the ffLuc transgene. A CD19-specific UCB-derived CD8+ T-cell clone was adoptively transferred into mice with growing tumors, and the longitudinal tumor-derived ffLuc-enzyme activity was evaluated in vivo using BLI. The mice in the group that received adoptive immunotherapy experienced a reduction in tumor bulk, with 60% of the mice obtaining a complete remission. All the mice in the control group, which received no cell-based therapy, experienced continued tumor growth. By calculating the cumulative area under the curve (AUC) for each mouse and then applying a permutation test for AUC means across all groups, we demonstrate that the antitumor effect achieved a statistical significance of P = .008.

Figure 6.

Elimination of established CD19+ tumor by adoptive transfer of UCB-derived CD19R+ T cells. (A) Longitudinal monitoring of bioluminescence quantification of Daudi tumor-derived ffLuc-activity in 2 groups of NOD/Scid mice (5 mice per group) and ffLuc-derived bioluminescent signals are graphed over time. (I) Group that received no cellular therapy and (II) group that received cellular therapy with CD8+ CD19-specific T-cell clone. Background bioluminescence (as measured in parallel from mouse with no tumor, but which did receive d-luciferin) was calculated for each group at each imaging time point. The red lines correspond to the in vivo optical bioluminescence images of tumor from one mouse selected from each group. (Genetically modified Daudi in vitro ffLuc-activity was 55.1 ± 2.2 CPM/cell [mean ± SD] compared to 0.072 ± 0.017 CPM/cell [mean ± SD] for parental unmodified cells.) (B) Movie still (see Video S2) of time lapse BLI of ffLuc+ Daudi in 2 NOD/Scid mice starting the day before adoptive immunotherapy. One mouse received adoptive transfer of CD8+ CD19-specific UCB-derived T-cell clone (left), and one mouse received no cellular therapy. Color bar displays relative ffLuc activity in units of p/s/cm2/sr.

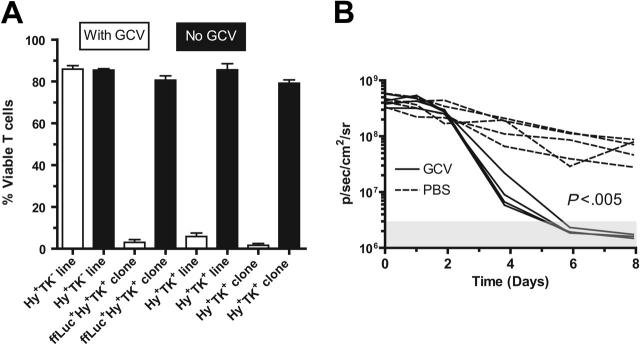

UCB-derived CD19-specific TK+ T cells can be eliminated by ganciclovir

Adoptive immunotherapy with donor-derived CD19-specific T cells after UCBT is anticipated to improve the GVL effect. However, adoptive transfer of these UCB-derived T cells may cause or exacerbate GVHD. Therefore, to improve patient safety, the CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor was coexpressed with the HyTK bifunctional selection/suicide gene in the plasmid CD19R/HyTK-pMG.17 An in vitro assay was developed to validate that the CD19R+HyTK+ T cells are sensitive to selective eradication by the prodrug. Using this assay, after 14 days of culture with 5 μM GCV, approximately 95% of UCB-derived T cells (clone and line) expressing the HSV-1–derived TK gene are killed, whereas UCB-derived genetically modified hygromycin-resistant T cells that do not express TK are apparently not eliminated by GCV (Figure 7A). The average number of viable TK+ T cells after 14 days of exposure to GCV was 0.43% to 0.93% of the number of cells grown in the absence of GCV. We also examined whether the HyTK+ T cells could be eliminated in vivo. To visualize noninvasively the survival of adoptively transferred T cells in mice, a new trifunctional suicide protein was developed fusing ffLuc with HyTK cDNAs to create the fusion gene ffLucHyTK. This multifunction gene was coexpressed along with the CD19R gene in the DNA expression plasmid designated CD19R/ffLucHyTK-pMG (Figure 1C,D). We adoptively transferred the UCB-derived T cells with the phenotype CD19R+ffLuc+HyTK+ into 2 groups of mice (Figure 7B). One group received GCV, and one group received PBS to control for the inherent loss of T cells in this model. The T-cell death was significantly faster in the GCV-treated group, compared with the group that received PBS (P < .005). The in vivo half-life of CD19-specific T cells in mice receiving PBS was approximately 2.1 days, and the half-life of CD19-specific T cells in mice receiving GCV was approximately 0.56 days. Even after stopping GCV the ffLuc-activity from T cells in the treatment group could not be detected above background flux for a further 12 days of imaging (data not shown).

Figure 7.

UCB-derived T cells genetically modified to express CD19R and TK genes are selectively eliminated by ganciclovir in vitro and in vivo. (A) UCB-derived T cells expressing TK gene can be eradicated by 5 μM GCV in vitro. The control Hy+TK– UCB-derived T-cell line was genetically modified with the plasmid HyMP1-pEK.21 Initially, 4 × 104 T cells plated/well in triplicate, and after 14 days the average viable cell count is presented as percentage of mean viable cells ± SD. (B) UCB-derived CD8+ CD19R+ffLucHyTK+ T cells can be ablated by GCV in vivo. T cells were stimulated in vivo with CD19+ tumor and exogenous rhIL-2 to promote T-cell persistence. Data are shown for 5 mice in each group (broken lines indicate mice that received PBS; solid lines, mice that received GCV). The background bioluminescence (mice that were injected with luciferin but which received no T cells) over the 12-day experiment for both the groups of mice receiving GCV or PBS was approximately 3 × 106 ± 106 a p/s/cm2/sr (mean ± SD) as represented by the shaded box. Genetically modified T-cell in vitro ffLuc-enzyme activity was 1.6 ± 0.1 CPM/cell (mean ± SD), compared with 0.008 ± 0.004 CPM/cell (mean ± SD) background ffLuc-enzyme activity in ffLucneg T cells.

CD19-specific T cells can be generated from residual mononuclear cells after infusion of UCB hematopoietic stem cells

To evaluate the feasibility of generating UCB-derived CD19-specific T cells for clinical infusion after UCBT, we determined whether genetically modified T cells could be generated from small numbers of cord-blood cells remaining in the tubing-set after infusion of the UCB-derived hematopoietic cells. These cells were stimulated with OKT3 and rhIL-2 and, after nonviral gene transfer with the linearized plasmid CD19R/HyTK-pMG and selection in a cytocidal concentration of hygromycin B, the genetically modified T cells could be numerically expanded on average 39 ± 11 (mean ± 1 SD) -fold over a 14-day growth cycle. These propagated T cells successfully expressed the CD19-specific chimeric immunoreceptor and demonstrated redirected specificity for CD19 (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of CD19R+ T cells from UCB obtained after transplantation

| UPN | Electroporated TNCs, no. | TNCs infused, % | Western blot chimeric CD3ζ (66 kDa) | Cytotoxicity by CRA with CD19+ target 5:1, % | Cytotoxicity by CRA with CD19- target 5:1, % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 001 | 6.6 × 106 | 0.45 | + | 59 | 15 |

| 002 | 4.0 × 106 | 0.78 | + | 39 | 1 |

| 003 | 1.6 × 107 | 1.73 | + | 47 | 14 |

UPN indicates unique patient number; TNCs, total nucleated cells.

Discussion

The inability of maximally intensive preparative regimens combined with immunologic graft-versus-tumor reactivity to eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD) is a mechanism of treatment failure after UCBT. Targeting CD19+ MRD early after HSCT by adoptive transfer of donor-derived tumor-specific T cells is one strategy to consolidate the tumor cytoreduction achieved with preparative regimens and establish tumor-specific immunosurveillance.

While UCB-derived T cells can be propagated ex vivo,43-49 the functional immaturity of T cells in circulating umbilical cord blood typically prevents ex vivo identification of endogenous leukemia/lymphoma-specific T cells. Therefore, we developed a genetic engineering strategy to introduce a chimeric immunoreceptor in order to generate UCB-derived T cells with desired specificity. We demonstrate that UCB-derived T cells can be rendered specific for CD19, expanded ex vivo, and observed to target CD19 specifically on malignant B cells in vitro and in vivo. Our approach uses methods that are currently in practice at our institution for phase 1/2 T-cell trials and that can be accomplished using small numbers of residual mononuclear cells remaining in the tubing set after infusion of UCB-derived hematopoietic stem cells.

Age-related differences in T-cell differentiation, activation, adhesion, and costimulatory molecules between T cells isolated from neonates and adults influence their relative ability to achieving fully competent activation.50-53 Although the starting population of T cells derived from UCB exhibited the markers for a naive population, they differentiated to an effector-cell phenotype after genetic manipulation, stimulation, and culture, and exhibited a similar pattern of cell-surface markers as CD19-specific effector T cells derived from adult PB, which are currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

VTLM was used to observe these killing events directly and to establish that UCB-derived T cells can disengage from a target after specific killing and recycle cytolysis. This recycling occurred despite the use of an scFv with a high affinity for CD19 (Ka ∼2 × 10–9M–1) compared with the low-affinity (micromolar range) binding of T-cell adhesion/costimulatory molecules.54,55 The time to achieve CD19R-mediated killing of CD19+ tumor cells can be compared to the lytic potential of T cells recognizing antigen through an endogenous TCR. Antigen-specific lysis of target cells, mediated by recognition of αβTCR of HLA and cognate antigen, by CD8+ T cells preloaded with cytotoxic granules can occur within 5 minutes, although the killing process can stretch out over hours.56 This compares with a mean of approximately 20 minutes for UCB-derived T cells to kill CD19+ tumor cells as revealed by morphologic changes. Future experiments using bispecific21 T cells coexpressing a TCR with a known specificity as well as CD19R will help determine if this difference in time to kill is due to the type of T cell used or is a function of relative antigen density and/or T-cell physiology.

The redirected cytolytic activity of UCB-derived T cells also was evaluated in vivo. The adoptive transfer of CD19-specific UCB-derived T cells was demonstrated to control tumor growth. Furthermore, the development of multifunction reporter genes,57,58 such as the trifunctional ffLucHyTK gene, allows BLI to demonstrate that the infused TK+ UCB-derived T cells can be eliminated in vivo by GCV-mediated ablation. This elimination may be critical in a clinical setting should adoptive immunotherapy lead to adverse events such as GVHD.

The CD19 molecule is expressed on most ALLs, chronic lymphocytic leukemias, and lymphomas of the B lineage.59,60 In vitro assays have indicated that progenitor cells of B-ALL express CD19.61,62 However, recent data have challenged this assertion by demonstrating that (1) sorted CD34+CD19– leukemic progenitors can give rise to B-ALL in NOD/Scid mice and, (2) that approximately 50% of immature CD34+CD19– bone marrow cells from children with high-risk B-cell precursor ALL are marked by chromosomal translocations present in peripheral blasts.63,64 Refuting these data are possible technical issues associated with down-modulation of CD19 due to in vitro culture of progenitor cells, and when using CD19-specific antibodies to stain cells,65 microarray analyses demonstrating that CD34+ leukemic B-cell progenitors expressed CD19,66 and that for some B-ALLs, leukemia-specific chromosomal translocations cannot be detected in the CD34+CD19– primitive lymphoid-restricted progenitor/stem-cell population.67 Additional investigation is needed to clarify this issue.

One of the criticisms of UCBT, compared with other unrelated sources of hematopoietic stem cells, has been that donor anonymity precludes augmenting the GVL effect by infusions of donor-derived lymphocytes.68-70 The ability to generate B-ALL–specific T cells from UCB by enforcing expression of a chimeric immunoreceptor provides a potential solution to this limitation. Furthermore, the setting of UCBT may be particularly well suited to adoptive immunotherapy, since the slow pace of hematopoietic recovery provides a period of relative lymphopenia in which adoptively transferred T cells might expand using homeostatic mechanisms inherent to recovering the lymphocyte pool, and the relatively low incidence of severe GVHD means that recipients will be less likely to be taking immunosuppressive medications that might impair the function and persistence of the adoptively transferred T cells. In aggregate, the data presented support a clinical trial to evaluate safety and feasibility of adoptive immunotherapy with CD19-specific UCB-derived T cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs Merrill Lewen and Bryan Jick at Huntington Memorial Hospital (Pasadena, CA) for assistance with procurement of umbilical cord blood, Dr Mark Sherman (COH's Division of Information Sciences) for assistance with molecular modeling, COH's flow cytometry facility (Lucy Brown, Manager), COH's VTLF (James Bolen, Manager), COH's Animal Resource Center under direction of Dr Richard Ermel, COH's Stem Cell Processing Laboratory (Candace Kay, Supervisor) in Department of Transfusion Medicine, Dr Stephen Hunger (University of Florida, College of Medicine, Gainesville, FL) and the Children's Oncology Group ALL cell bank for providing primary ALL samples, Dr Waldemar Debinski (Wake Forest University, NC) for providing U251T cells, and Dr Julie Mayo for editorial assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, December 13, 2005; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-09-3904.

Supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants CA30206, CA003572, and CA107399; the Alliance for Cancer Gene Therapy; the Amy Phillips Charitable Foundation; the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society; the Lymphoma Research Foundation; the National Foundation for Cancer Research; the Pediatric Cancer Research Foundation; the National Marrow Donor Program; and the Marcus Foundation.

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

- 1.Rubinstein P, Carrier C, Scaradavou A, et al. Outcomes among 562 recipients of placental-blood transplants from unrelated donors. N Engl J Med. 1998;339: 1565-1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Porter DL, June CH. T-cell reconstitution and expansion after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation:'T' it up! Bone Marrow Transplant. 2005;35: 935-942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Warren EH, Gavin M, Greenberg PD, Riddell SR. Minor histocompatibility antigens as targets for T-cell therapy after bone marrow transplantation. Curr Opin Hematol. 1998;5: 429-433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nijmeijer BA, Willemze R, Falkenburg JH. An animal model for human cellular immunotherapy: specific eradication of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia by cytotoxic T lymphocytes in NOD/scid mice. Blood. 2002;100: 654-660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298: 850-854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walter EA, Greenberg PD, Gilbert MJ, et al. Reconstitution of cellular immunity against cytomegalovirus in recipients of allogeneic bone marrow by transfer of T-cell clones from the donor. N Engl J Med. 1995;333: 1038-1044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rooney CM, Aguilar LK, Huls MH, Brenner MK, Heslop HE. Adoptive immunotherapy of EBV-associated malignancies with EBV-specific cytotoxic T-cell lines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2001;258: 221-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Einsele H. Antigen-specific T cells for the treatment of infections after transplantation. Hematol J. 2003;4: 10-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanson HL, Donermeyer DL, Ikeda H, et al. Eradication of established tumors by CD8+ T cell adoptive immunotherapy. Immunity. 2000;13: 265-276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss P, Rickinson A. Cellular immunotherapy for viral infection after HSC transplantation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5: 9-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper LJ, Kalos M, Lewinsohn DA, Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. Transfer of specificity for human immunodeficiency virus type 1 into primary human T lymphocytes by introduction of T-cell receptor genes. J Virol. 2000;74: 8207-8212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan BL, Yu DC, Clay TM, Nishimura MI. Redirecting T lymphocyte specificity using T cell receptor genes. Int Rev Immunol. 2003;22: 229-253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper LJ, Al-Kadhimi Z, DiGiusto D, et al. Development and application of CD19-specific T cells for adoptive immunotherapy of B cell malignancies. Blood Cells Mol Dis. 2004;33: 83-89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gonzalez S, Naranjo A, Serrano LM, Chang WC, Wright CL, Jensen MC. Genetic engineering of cytolytic T lymphocytes for adoptive T-cell therapy of neuroblastoma. J Gene Med. 2004;6: 704-711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang J, Press OW, Lindgren CG, et al. Cellular immunotherapy for follicular lymphoma using genetically modified CD20-specific CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Mol Ther. 2004;9: 577-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen MC, Cooper LJ, Wu AM, Forman SJ, Raubitschek A. Engineered CD20-specific primary human cytotoxic T lymphocytes for targeting B-cell malignancy. Cytotherapy. 2003;5: 131-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooper LJ, Topp MS, Serrano LM, et al. T-cell clones can be rendered specific for CD19: toward the selective augmentation of the graft-versus-B-lineage leukemia effect. Blood. 2003;101: 1637-1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Roessig C, Scherer SP, Baer A, et al. Targeting CD19 with genetically modified EBV-specific human T lymphocytes. Ann Hematol. 2002;81: 42-43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brentjens RJ, Latouche JB, Santos E, et al. Eradication of systemic B-cell tumors by genetically targeted human T lymphocytes costimulated by CD80 and interleukin-15. Nat Med. 2003;9: 279-286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Imai C, Mihara K, Andreansky M, et al. Chimeric receptors with 4-1BB signaling capacity provoke potent cytotoxicity against acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia. 2004;18: 676-684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cooper LJ, Al-Kadhimi Z, Serrano LM, et al. Enhanced antilymphoma efficacy of CD19-redirected influenza MP1-specific CTLs by cotransfer of T cells modified to present influenza MP1. Blood. 2005;105: 1622-1631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Imai C, Iwamoto S, Campana D. Genetic modification of primary natural killer cells overcomes inhibitory signals and induces specific killing of leukemic cells. Blood. 2005;106: 376-383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eshhar Z, Waks T, Gross G, Schindler DG. Specific activation and targeting of cytotoxic lymphocytes through chimeric single chains consisting of antibody-binding domains and the gamma or zeta subunits of the immunoglobulin and T-cell receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90: 720-724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gonzalez S, Castanotto D, Li H, et al. Amplification of RNAi—targeting HLA mRNAs. Mol Ther. 2005;11: 811-818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lupton SD, Brunton LL, Kalberg VA, Overell RW. Dominant positive and negative selection using a hygromycin phosphotransferase-thymidine kinase fusion gene. Mol Cell Biol. 1991;11: 3374-3378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Klein E, Klein G, Nadkarni JS, Nadkarni JJ, Wigzell H, Clifford P. Surface IgM-kappa specificity on a Burkitt lymphoma cell in vivo and in derived culture lines. Cancer Res. 1968;28: 1300-1310. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahmoud MS, Fujii R, Ishikawa H, Kawano MM. Enforced CD19 expression leads to growth inhibition and reduced tumorigenicity. Blood. 1999;94: 3551-3558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klein E, Ben-Bassat H, Neumann H, et al. Properties of the K562 cell line, derived from a patient with chronic myeloid leukemia. Int J Cancer. 1976;18: 421-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koeffler HP, Golde DW. Human myeloid leukemia cell lines: a review. Blood. 1980;56: 344-350. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Riddell SR, Greenberg PD. The use of anti-CD3 and anti-CD28 monoclonal antibodies to clone and expand human antigen-specific T cells. J Immunol Methods. 1990;128: 189-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rufer N, Zippelius A, Batard P, et al. Ex vivo characterization of human CD8+ T subsets with distinct replicative history and partial effector functions. Blood. 2003;102: 1779-1787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hamann D, Baars PA, Rep MH, et al. Phenotypic and functional separation of memory and effector human CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;186: 1407-1418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geginat J, Lanzavecchia A, Sallusto F. Proliferation and differentiation potential of human CD8+ memory T-cell subsets in response to antigen or homeostatic cytokines. Blood. 2003;101: 4260-4266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sanders ME, Makgoba MW, Sharrow SO, et al. Human memory T lymphocytes express increased levels of three cell adhesion molecules (LFA-3, CD2, and LFA-1) and three other molecules (UCHL1, CDw29, and Pgp-1) and have enhanced IFN-gamma production. J Immunol. 1988;140: 1401-1407. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Varis I, Deneys V, Mazzon A, De Bruyere M, Cornu G, Brichard B. Expression of HLA-DR, CAM and co-stimulatory molecules on cord blood monocytes. Eur J Haematol. 2001;66: 107-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Risdon G, Gaddy J, Horie M, Broxmeyer HE. Alloantigen priming induces a state of unresponsiveness in human umbilical cord blood T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92: 2413-2417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barbey C, Irion O, Helg C, et al. Characterisation of the cytotoxic alloresponse of cord blood. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1998;22: 26-30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang XN, Sviland L, Ademokun AJ, et al. Cellular alloreactivity of human cord blood cells detected by T-cell frequency analysis and a human skin explant model. Transplantation. 1998;66: 903-909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keever CA, Abu-Hajir M, Graf W, et al. Characterization of the alloreactivity and anti-leukemia reactivity of cord blood mononuclear cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 1995;15: 407-419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yang YC, Hsu TY, Chen JY, Yang CS, Lin RH. Tumour necrosis factor-alpha–induced apoptosis in cord blood T lymphocytes: involvement of both tumour necrosis factor receptor types 1 and 2. Br J Haematol. 2001;115: 435-441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Revy P, Sospedra M, Barbour B, Trautmann A. Functional antigen-independent synapses formed between T cells and dendritic cells. Nat Immunol. 2001;2: 925-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Inaba K, Romani N, Steinman RM. An antigen-independent contact mechanism as an early step in T cell-proliferative responses to dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 1989;170: 527-542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lin SJ, Yu JC, Cheng PJ, Hsiao SS, Kuo ML. Effect of interleukin-15 on anti-CD3/anti-CD28 induced apoptosis of umbilical cord blood CD4+ T cells. Eur J Haematol. 2003;71: 425-432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lin SJ, Wang LY, Huang YJ, Kuo ML. Effect of interleukin (IL)-12 and IL-15 on apoptosis and proliferation of umbilical cord blood mononuclear cells. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2001;28: 439-445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kim YM, Jung MH, Song HY, et al. Ex vivo expansion of human umbilical cord blood-derived T-lymphocytes with homologous cord blood plasma. Tohoku J Exp Med. 2005;205: 115-122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skea D, Chang NH, Hedge R, et al. Large ex vivo expansion of human umbilical cord blood CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. J Hematother. 1999;8: 129-139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Azuma H, Yamada Y, Shibuya-Fujiwara N, et al. Functional evaluation of ex vivo expanded cord blood lymphocytes: possible use for adoptive cellular immunotherapy. Exp Hematol. 2002;30: 346-351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson KL, Ayello J, Hughes R, et al. Ex vivo expansion, maturation, and activation of umbilical cord blood–derived T lymphocytes with IL-2, IL-12, anti-CD3, and IL-7: potential for adoptive cellular immunotherapy post-umbilical cord blood transplantation. Exp Hematol. 2002;30: 245-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Migliaccio AR, Alfani E, Di Giacomo V, Cieri M, Migliaccio G. Ex vivo amplification of T cells from human cord blood. Pathol Biol. 2005;53: 151-158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris DT, Schumacher MJ, Locascio J, et al. Phenotypic and functional immaturity of human umbilical cord blood T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89: 10006-10010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tucci A, Mouzaki A, James H, Bonnefoy JY, Zubler RH. Are cord blood B cells functionally mature? Clin Exp Immunol. 1991;84: 389-394. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Taylor S, Bryson YJ. Impaired production of gamma-interferon by newborn cells in vitro is due to a functionally immature macrophage. J Immunol. 1985;134: 1493-1497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sato K, Kawasaki H, Nagayama H, et al. Chemokine receptor expressions and responsiveness of cord blood T cells. J Immunol. 2001;166: 1659-1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nicholson IC, Lenton KA, Little DJ, et al. Construction and characterisation of a functional CD19 specific single chain Fv fragment for immunotherapy of B lineage leukaemia and lymphoma. Mol Immunol. 1997;34: 1157-1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Davis MM, Krogsgaard M, Huppa JB, et al. Dynamics of cell surface molecules during T cell recognition. Annu Rev Biochem. 2003;72: 717-742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stinchcombe JC, Bossi G, Booth S, Griffiths GM. The immunological synapse of CTL contains a secretory domain and membrane bridges. Immunity. 2001;15: 751-761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Soling A, Theiss C, Jungmichel S, Rainov NG. A dual function fusion protein of Herpes simplex virus type 1 thymidine kinase and firefly luciferase for noninvasive in vivo imaging of gene therapy in malignant glioma. Genet Vaccines Ther. 2004;2: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jacobs A, Dubrovin M, Hewett J, et al. Functional coexpression of HSV-1 thymidine kinase and green fluorescent protein: implications for noninvasive imaging of transgene expression. Neoplasia. 1999;1: 154-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Uckun FM, Jaszcz W, Ambrus JL, et al. Detailed studies on expression and function of CD19 surface determinant by using B43 monoclonal antibody and the clinical potential of anti-CD19 immunotoxins. Blood. 1988;71: 13-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Anderson KC, Bates MP, Slaughenhoupt BL, Pinkus GS, Schlossman SF, Nadler LM. Expression of human B cell–associated antigens on leukemias and lymphomas: a model of human B cell differentiation. Blood. 1984;63: 1424-1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Uckun FM, Haissig S, Ledbetter JA, et al. Developmental hierarchy during early human B-cell ontogeny after autologous bone marrow transplantation using autografts depleted of CD19+ B-cell precursors by an anti-CD19 pan–B-cell immunotoxin containing pokeweed antiviral protein. Blood. 1992;79: 3369-3379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uckun FM, Ledbetter JA. Immunobiologic differences between normal and leukemic human B-cell precursors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85: 8603-8607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cox CV, Evely RS, Oakhill A, Pamphilon DH, Goulden NJ, Blair A. Characterization of acute lymphoblastic leukemia progenitor cells. Blood. 2004;104: 2919-2925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hotfilder M, Rottgers S, Rosemann A, et al. Leukemic stem cells in childhood high-risk ALL/t(9; 22) and t(4;11) are present in primitive lymphoid-restricted CD34+CD19– cells. Cancer Res. 2005;65: 1442-1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Campana D, Iwamoto S, Bendall L, Bradstock K. Growth requirements and immunophenotype of acute lymphoblastic leukemia progenitors. Blood. 2005;105: 4150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Anthony J, George A, Senadheera S, et al. Comparison of gene expression by normal and leukemic progenitor cells in childhood B cell precursor ALL: are there ALL stem cells [abstract]. Blood. 2004;104: 2045. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hotfilder M, Rottgers S, Rosemann A, Jurgens H, Harbott J, Vormoor J. Immature CD34+CD19– progenitor/stem cells in TEL/AML1-positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia are genetically and functionally normal. Blood. 2002;100: 640-646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ballen KK. New trends in umbilical cord blood transplantation. Blood. 2005;105: 3786-3792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barker JN, Wagner JE. Umbilical-cord blood transplantation for the treatment of cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3: 526-532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grewal SS, Barker JN, Davies SM, Wagner JE. Unrelated donor hematopoietic cell transplantation: marrow or umbilical cord blood? Blood. 2003;101: 4233-4244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whitlow M, Bell BA, Feng SL, et al. An improved linker for single-chain Fv with reduced aggregation and enhanced proteolytic stability. Protein Eng. 1993;6: 989-995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Reddy MP, Kinney CA, Chaikin MA, et al. Elimination of Fc receptor–dependent effector functions of a modified IgG4 monoclonal antibody to human CD4. J Immunol. 2000;164: 1925-1933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kabat EA, Wu TT, Perry HM, Gottesman KS, Foeller C. Sequences of proteins of immunological interest: NIH Publication no. 91-3242 (5 ed). Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 1991.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.