Abstract

Most non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs) are of B-cell origin, but the tumor tissue can be variably infiltrated with T cells. In the present study, we have identified a subset of CD4+CD25+ T cells with high levels of CTLA-4 and Foxp3 (intratumoral Treg cells) that are overrepresented in biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL (median of 17% in lymphoma biopsies, 12% in inflammatory tonsil, and 6% in tumor-free lymph nodes; P = .001). We found that these CD4+CD25+ T cells suppressed the proliferation and cytokine (IFN-γ and IL-4) production of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in response to PHA stimulation. PD-1 was found to be constitutively and exclusively expressed on a subset of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells, and B7-H1 could be induced on intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells in B-cell NHL. Anti-B7-H1 antibody or PD-1 fusion protein partly restored the proliferation of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells when cocultured with intratumoral Treg cells. Finally, we found that CCL22 secreted by lymphoma B cells is involved in the chemotaxis and migration of intratumoral Treg cells that express CCR4, but not CCR8. Taken together, our results suggest that Treg cells are highly represented in the area of B-cell NHL and that malignant B cells are involved in the recruitment of these cells into the area of lymphoma.

Introduction

B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a serious and frequently fatal illness. The clinical course of this disease is variable, and the molecular and cellular mechanisms responsible for the clinical heterogeneity of B-cell NHL are largely unknown. However, it is becoming increasing clear that the tumor microenvironment plays an important role in the disease severity, clinical outcome, and response to therapy.1-3 In previous work, we have shown that the presence of increased numbers of activated intratumoral CD4+ T cells predicts a better overall survival in patients with lymphoma.4 These findings suggest that intratumoral T cells may play a role in the regulation of tumor cell growth in patients with lymphoma.

Recent studies have highlighted the significance of regulatory T cells in the immune system.5,6 The CD4+CD25+ subset (Treg cells) has been extensively studied and found to suppress autoimmune T-cell responses and to maintain peripheral tolerance.5,6 Treg cells represent approximately 5% to 10% of peripheral CD4+ T cells in both mice and humans.7-10 In addition to sustained high surface expression of CD25, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4) and glucocorticoid-induced TNFR-related protein (GITR) expression are features of suppressive Treg cells (see Curotto de Lafaille et al11 and Hori et al12 for review). Expression of forkhead box P3 (Foxp3), a transcriptional factor, has been demonstrated to be confined to Treg cells at both mRNA and protein levels,13-15 and studies indicated that Foxp3 is crucial to the development of Treg cells in a murine model and for protection from a fatal autoimmune disease.14

Although it is clear that Treg cells have functional significance in the immune system, the precise mechanism of suppression by Treg cells is poorly understood. Studies indicate that suppression requires direct cell contact between Treg cells and target T cells exclusively in in vitro experiment models.16 Furthermore, it appears that human Treg cells must be activated through their T-cell receptor (TCR) to be operationally suppressive.17 Suppression by Treg cells is independent of cytokines such as IL-10. Whether TGF-β and CTLA-4 or other inhibitory costimulatory molecules such as B7-H1 are critical for Treg cell-mediated suppression is currently controversial.18-21

Although first identified for their ability to prevent organ-specific autoimmune disease in mice,22-24 emerging evidence suggests that Treg cells are involved in the regulation of antitumor immunity.25-31 Consistent with this concept, experimental depletion of Treg cells in mice with tumors improves immune-mediated tumor clearance27 and enhances the response to immune-based therapy.32 Treg cells have been shown to suppress tumor-specific T-cell immunity and therefore may contribute to the progression of human tumors.33-36 Furthermore, tumor Treg cells are associated with a reduced survival in patients with ovarian carcinoma.35 In contrast, it has been found in Hodgkin lymphoma that decreased numbers of infiltrating Foxp3+ cells in conjunction with increased infiltration of cytotoxic T lymphocytes predicts an unfavorable clinical outcome.36 In the present study, we investigated the significance of intratumoral Treg cells in the regulation of the local immune response in B-cell NHL. We found that CD4+CD25+ T cells with intracellular Foxp3 and CTLA-4 expression are overrepresented in the tumor sites of B-cell NHL and suppress the proliferation of and cytokine production by infiltrating CD4+CD25+ T cells.

Patients, materials, and methods

Antibodies and reagents

The fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for surface staining (CD4, CD7, CD25, CD45RA, CD45RO, CD80, CD86, CD152, CD154, HLA-II) were obtained from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA). Alexa 488-conjugated anti-human Foxp3 antibody was purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). PE-conjugated anti-PD1 and anti-B7-H1 antibodies, purified anti-B7-H1, and isotype control antibodies (sodium azide free) as well as PD-1 fusion protein were purchased from Biosource (Camarillo, CA). Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) was obtained from Sigma (St Louis, MO). The following antibodies and reagents were purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN): PE-conjugated anti-CCR4, CCR8, CCL17, CCL22 antibodies, purified anti-CCL17, CCL22 antibodies, and human IFN-γ and IL-4 enzyme-linked immunospot (ELISPOT) kits. The 5-(and-6)-carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFSE) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR). CD4+, CD25+, and CD4+CD25+ cell isolation kits as well as LD and MS selection columns were purchased from Miltenyi Biotec (Auburn, CA). Calcein AM was obtained from Calbiochemical (La Jolla, CA), and chemotaxis kit was purchased from NeuroProbe (Pleasanton, CA).

Patient samples

Patients, providing written informed consent, were eligible for this study if they had a tissue biopsy that on pathologic review showed B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The biopsy specimens were reviewed and classified using the World Health Organization (WHO) lymphoma classification. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Mayo Clinic/Mayo Foundation. Biopsy specimens from 24 patients were analyzed.

Cell isolation and purification

Fresh tumor biopsy specimens were gently minced over a wire mesh screen to obtain a cell suspension. The cell suspension was centrifuged over Ficoll Hypaque at 500g for 15 minutes to isolate mononuclear cells and then washed with RPMI 1640 media. CD4+CD25- or CD4+CD25+ T-cell subsets were purified by using CD4+CD25+ Regulatory T-cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec). Purity was checked by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) analysis and was typically greater than 95%.

Flow cytometry and intracellular staining

Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 0.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) and incubated with specific fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies (Abs) and analyzed on a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ). For Foxp3 and CTLA-4 intracellular staining, cell suspensions from freshly isolated B-cell NHL biopsy specimens were incubated with Percp-anti-CD4 and APC-anti-CD25 Abs for 30 minutes at 4°C, washed, and fixed with Foxp3 Fix/Perm solution from BioLegend for 20 minutes at room temperature. After washing, cells were permeabilized with BioLegend's Foxp3 Perm buffer for 20 minutes at room temperature. Cells were then stained with Alexa 488-conjugated antihuman Foxp3 Ab and PE-conjugated anti-CTLA-4 Ab for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry. We calculated the frequency of intracellular Foxp3 and CTLA-4 in different subsets of infiltrating CD4+ T cells in B-cell NHL. Isotype controls were done for each sample.

CFSE labeling and T-cell proliferation assay

Cells were washed, counted, and resuspended at 1 × 107/mL in PBS. A stock solution of CFSE (5 mM) was diluted 1:100 with PBS and added to the cells for a final concentration of 5 μM. After 10 minutes at 37°C, cells were washed 3 times with PBS containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). CFSE-labeled responding cells were cocultured with or without stimulating cells in the presence or absence of PHA (2.5 μg/mL) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Cells were harvested at day 5, washed, and stained with fluorochrome-conjugated antibodies for detection of surface markers for 30 minutes at 4°C. Cells were then acquired for determining CFSE intensity on FACSCalibur. CFSEdim cells were measured and calculated as the percentage of proliferated cells.

ELISPOT

Secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 by an unsorted cell population, by CD4+ T cells, and by CD4+CD25- T cells was examined using an IFN-γ and IL-4 ELISPOT Kit according to manufacturer's instruction. Briefly, 100 μL unsorted cells, CD4+CD25-, or CD4+ T cells (2 × 105) were put into each well and incubated in a humidified 37°C CO2 incubator for 48 hours. After washing, 100 μL detection antibody was added to each well and incubated at 2°C to 8°C overnight. Cells were washed, and 100 μL streptavidin-AP was added to each well and incubated for 2 hours at room temperature. After washing, 100 μL BCIP/NBT chromogen was added, and cells were incubated for 1 hour at room temperature. The chromogen solution was discarded from the microplate; the microplate was rinsed and dried at room temperature (60-90 minutes). The developed microplate was analyzed using an automated ELISPOT reader. Results were expressed as the number of spot-forming cells (SFCs) per number of cells (normalized to 5 × 105) added to the well.

In vitro chemotaxis and migration assay

Chemotaxis and migration of intratumoral Treg cells in response to chemokines or culture supernatant of lymphoma B cells were assayed by using ChemoTx System (NeuroProbe) according to the manufacturer's protocol with a slight modification. Briefly, CCL22, CCL17 (200 ng/mL), or supernatant from CD20+ lymphoma B cells cultured for 48 hours were added (299 μL/well) to the lower chamber of the ChemoTx System and served as chemoattractants. Anti-CCL22 and anti-CCL17 antibodies (2 μg/mL) were used to block the activity of chemokines secreted in the culture supernatant by the CD20+ lymphoma B-cell population. CD4+CD25+ T cells were labeled with calcein AM (5 μg/mL) for 30 minutes at 37°C, washed, and resuspended in PBS. Labeled CD4+CD25+ T-cell (1 × 105) suspensions were added (24 μL/well) to the upper chamber of the ChemoTx System (5-μm pore size filter) and incubated for 60 minutes at 37°C 5% CO2. The chemotaxis chamber was placed in a multiwell fluorescent plate reader CytoFluor II (PerSeptive Biosystems, Framingham, MA), and the cells that migrated into the bottom chamber were measured by fluorescence signal.

Results

Elevated numbers of intratumoral CD4+CD25+ Treg cells in B-cell NHL

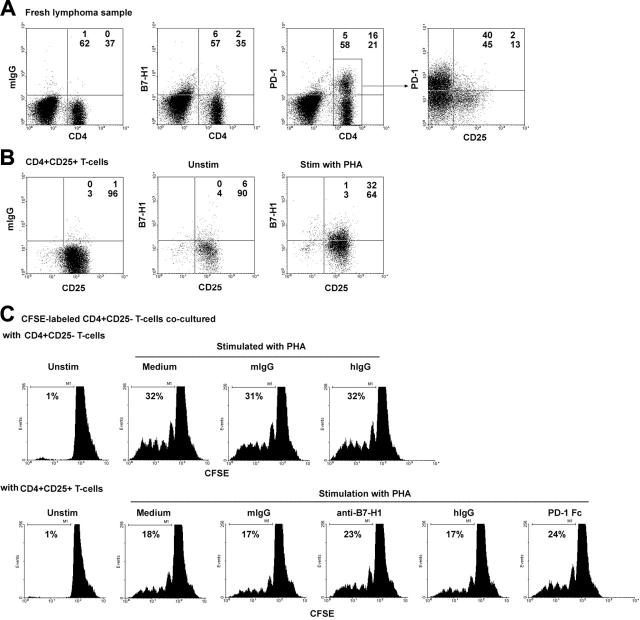

To evaluate a possible role of intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells in the tumor microenvironment of B-cell NHL, we first characterized the percentage of CD4+CD25+ cells in biopsy specimens of patients with B-cell NHL. The characteristics of the 24 patients with B-cell NHL whose specimens were used in this study are listed in Table 1. Cells isolated from biopsy specimens in B-cell NHL were stained with multicolor antibodies and analyzed by flow cytometry. For comparison, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from healthy individuals, and cells from tumor cell-free tonsils and lymph nodes were used as controls (Figure 1A). A variable amount of CD4+ T cells (median, 19.4%; range, 0.4%-64%) were seen in the B-cell NHL biopsy specimens. Among the CD4+ subset of T cells, a population of CD25+ cells with a clear CD25high expression could be detected. The frequency of CD4+CD25+ T cells was significantly higher in biopsy specimens from B-cell NHL (17% of the total CD4+ T cells, range, 6%-43%, n = 10) compared with those from PBMCs from healthy individuals (8%, range, 4%-9%, n = 5) or in normal tonsils (11%, range, 5%-19%, n = 6) or tumor cell-free lymph nodes (6%, range, 2%-9%, n = 6) (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of patients with B-cell NHL

| Patient no. | Hem ID | Sex | Age, y | Histology | Biopsy date | Treatment | Tissue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MF634 | M | 40 | DLBCL | 6/28/2004 | New | Node |

| 2 | MF644 | M | 69 | DLBCL | 7/9/2004 | New | Spleen |

| 3 | MF650 | F | 60 | DLBCL | 7/13/2004 | New | Spleen |

| 4 | MF659 | F | 86 | Foll g1 | 7/20/2004 | Leuk, ritux | Node |

| 5 | MF678 | M | 65 | SLL | 7/29/2004 | New | Node |

| 6 | MF685 | F | 88 | Foll g2 | 8/5/2004 | New | Node |

| 7 | MF702 | M | 66 | Foll g1 | 8/20/2004 | R-CVP | Node |

| 8 | MF779 | M | 50 | Foll g2 | 10/29/2004 | CHOP | Node |

| 9 | MF824 | M | 61 | DLBCL | 12/1/2004 | New | Extra |

| 10 | MF825 | M | 51 | Foll g1 | 12/1/2004 | Ritux | Node |

| 11 | MF849 | M | 70 | DLBCL | 12/28/2004 | Fludara | Node |

| 12 | MF886 | F | 42 | Foll g3 | 2/1/2005 | Leuk, ritux | Node |

| 13 | MF965 | M | 67 | Foll g3 | 4/7/2005 | CHOP | Node |

| 14 | MF974 | M | 48 | DLBCL | 4/12/2005 | FND | Spleen |

| 15 | MF978 | M | 68 | DLBCL | 4/14/2005 | New | Node |

| 16 | MF995 | M | 73 | Foll g2 | 4/27/2005 | New | Node |

| 17 | MF1005 | M | 56 | High gr | 5/6/2005 | R-CHOP | Spleen |

| 18 | MF1024 | M | 73 | MCL | 5/16/2005 | New | Spleen |

| 19 | MF1050 | F | 75 | Foll gr1 | 5/24/2005 | New | Node |

| 20 | MF1054 | F | 55 | Foll gr1 | 5/26/2005 | New | Node |

| 21 | MF1059 | M | 66 | MCL | 6/1/2005 | New | Extra |

| 22 | MF1062 | F | 49 | Foll gr1 | 6/3/2005 | New | Node |

| 23 | MF1065 | M | 52 | Foll gr1 | 6/4/2005 | CHOP | Extra |

| 24 | MF1076 | M | 69 | High gr | 6/14/2005 | New | Node |

DLBCL indicates diffuse large B-cell lymphoma; new, newly diagnosed and untreated; foll g1, follicular grade 1; leuk, Leukeran; ritux, rituximab; SLL, small lymphocytic lymphoma; foll g2, follicular grade 2; R-CVP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; CHOP, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; extra, extranodal; fludara, fludarabine; foll g3, follicular grade 3; FND, fludarabine, mitoxantrone, and dexamethasone; high gr, high-grade B-cell lymphoma otherwise unspecified; R-CHOP, rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone; MCL, mantle cell lymphoma; and Hem ID, Hematology Research Laboratory identification number.

Figure 1.

Antigen expression on CD4+CD25+ T cells from biopsy specimens of patients with B-cell NHL. (A) Dot plots showing CD25 expression on CD4+ T cells in freshly isolated cell suspensions from the tissue types indicated. (B) Frequency (mean ± SD) of CD4+CD25+ among normal peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) (n = 6), cells from inflammatory tonsils (n = 6), and benign/reactive LNs (n = 6). *P < .001, compared with benign/reactive LNs. (C) The phenotypic analysis of CD4+CD25+ T cells in B-cell NHL. The line was drawn based on the isotype control. The set of histograms is a representative of 6 samples. (D) Dot plots showing intracellular staining of Foxp3 or CTLA-4 as well as their corresponding isotype control in CD3+ CD4+CD25+/- T cells. Patient sample nos. 1 to 4, nos. 6 to 11, and no. 24 were used in these experiments.

Next, we determined the phenotype of the CD4+CD25+ T cells present in B-cell NHL tumors. We chose memory markers (CD45RA, CD45RO, CD27), activation markers (HLA-DR, HLA-II), and costimulatory markers (CD154, CD152, CD80, CD86) (Figure 1C). The CD4+CD25+ T cells were found to be CD7bright and had high expression of CD45RO combined with low expression of CD45RA, indicating that the cells were memory T cell-like. The costimulatory molecules CD154, CD80, and CD86 could not be detected on the surface of intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells, whereas HLA-DR and HLA-II were variably expressed. Some of the CD4+CD25+ T cells had surface expression of CD152 (CTLA-4).

We next wanted to determine whether the population of CD4+CD25+ T cells found in NHL tumors were Treg cells. Because CD25 is a common activation marker, its expression alone cannot be used to distinguish Treg cells from activated effector T cells. Expression of intracellular Foxp3 and CTLA-4 has been identified as a feature of Treg cells.11,13-15 Therefore, we examined intracellular expression of Foxp3 and CTLA-4 expression in CD4+CD25+ T cells isolated from biopsy specimens of patients with B-cell NHL (Figure 1D). T cells were stained with antibodies specific for CD4, CD25, Foxp3, and CTLA-4, or their corresponding isotype control. The vast majority of CD4+CD25+ T cells (90%) expressed high levels of intracellular Foxp3 and CTLA-4. Although some of CD4+CD25- T cells also expressed intracellular Foxp3, the fluorescence intensity of Foxp3 expression in CD4+CD25- T cells was lower than that in CD4+CD25+ T cells. Moreover, these CD4+Foxp3+ cells actually were CD25low cells rather than CD4+CD25- cells that completely lacked the expression of intracellular Foxp3 expression. These data suggest that phenotypically the CD4+CD25+ cells found in NHL tumors are Treg cells. We also performed reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) experiments to detect Foxp3 mRNA expression. Similarly, the Foxp3 mRNA level was higher in CD4+CD25+ T cells than in CD4+CD25- T cells (data not shown).

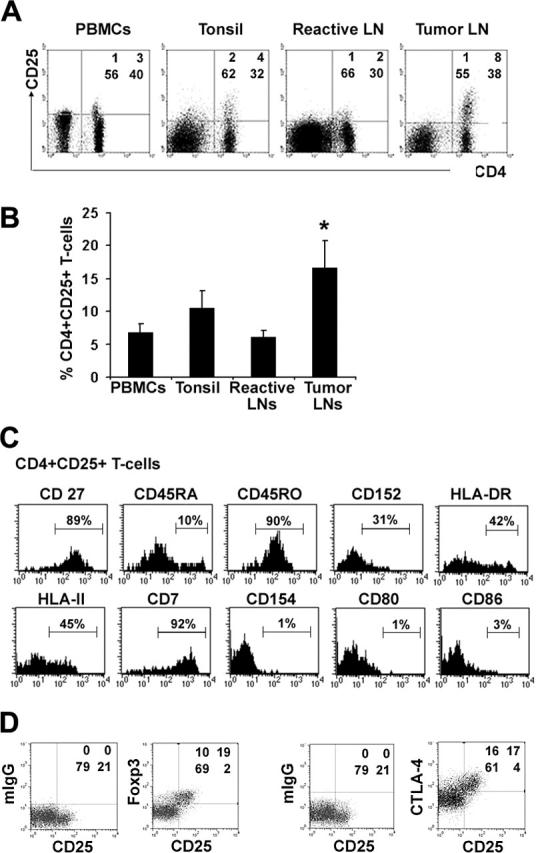

Intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells suppress proliferation of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL

We next wanted to determine whether intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells were able to suppress the proliferative capacity of CD4+CD25- cells isolated from NHL biopsies. CD4+CD25- T cells (responding cells) were labeled with CFSE and cocultured with CD4+CD25+ T cells (1:4 ratio) in the presence or absence of PHA for 5 days. As a control, CD4+CD25- T cells were also cocultured with CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- cells. In the presence of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells, the number of CD4+CD25- T cells that had undergone cell division declined from 33% to 16%, as indicated by the percentage of CFSEdim population (Figure 2A). However, there was no significant difference in the number of cell divisions seen between the 2 populations. When we combined the results from multiple experiments, we saw a 49% ± 3.8% reduction (mean ± SD) in cell proliferation in the presence of Treg compared with CD4+CD25- (n = 7, P < .01). To confirm our results from Figure 2A, we tested the effect of CD25 depletion on the proliferation of CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL. Three subpopulations, CD4+CD25+ T cells, CD4+CD25- T cells, and CD25-depleted cells (non-CD25+ cells), were isolated from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL. Although CD25 expression is not confined to CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells can express CD25 in an early activation stage, in our samples, around 95% of CD25+ cells are CD3+CD4+ T cells and the majority of CD8+ T cells are CD25- (data not shown). Therefore, CD25 depletion accounts for the depletion of almost all CD4+CD25+ T-cells. The CD25-depleted cell population (non-CD25+ cells) was labeled with CFSE and cultured either with CD4+CD25- or CD4+CD25+ T cells in the presence or absence of PHA for 5 days. The cells were analyzed by FACS with multicolor staining and gated on CD3+CD4+ cells. As shown in Figure 2B, the addition of CD4+CD25+ T cells suppressed the proliferation of CD4+ T cells compared with the addition of CD4+CD25- T cells (35% versus 68%). Of note, we found that some of the CD4+CD25- cells also had an inhibitory effect on intratumoral CD4+ cells, leading to a more modest difference between the cell types than expected. Taken together, these results suggest that intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells are capable of inhibiting the proliferation of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL.

Figure 2.

Intratumoral Treg cells suppressed autologous infiltrating CD4+CD25- T-cell proliferation. Isolated CD4+CD25- T cells (A) or CD25-depleted cell suspensions (B) from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL were labeled with CFSE and cocultured with either CD4+CD25- T cells or CD4+CD25+ T cells in the presence or absence of PHA for 5 days. CFSEdim cells were measured as a percentage of the proliferated cells. The histogram shown is representative of 7 and 3 samples for panels B and C, respectively. Patient sample nos. 7 to 9 and nos. 20 to 23 were used in these experiments.

Intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells inhibit the production and secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 by infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL

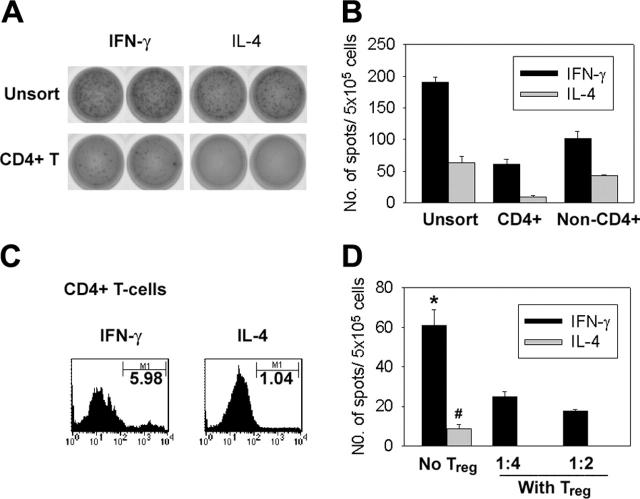

We next wanted to determine whether intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells could inhibit cytokine production by infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells. ELISPOT and intracellular staining techniques were used to determine the production and secretion of IFN-γ and IL-4 by infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells. By ELISPOT (Figure 3A-B), we found that IFN-γ and IL-4 were produced and secreted on PHA stimulation in unsorted, CD4+, and non-CD4+ cells from cell suspensions from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL (n = 6). Our results indicate that there were more IFN-γ-producing CD4+ T cells than IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells in infiltrates of B-cell NHL (Figure 3B). These results were confirmed by intracellular IFN-γ and IL-4 staining, in which 6% of CD4+ T cells were IFN-γ-positive cells and 1% were IL-4-positive cells (Figure 3C). We then tested the effect of intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells on cytokine production and secretion by infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells. By ELISPOT, we found that incubation with CD4+CD25+ T cells markedly suppressed IFN-γ and completely blocked IL-4 secretion by CD4+CD25- T cells on PHA stimulation (Figure 3D). The results indicate that inhibition of cytokine production by infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells may be one of the mechanisms by which CD4+CD25+ T cells mediate suppression of cell division. These results, in accordance with our phenotypic data (Figure 1C-D), reveal that the CD4+CD25+ T cells isolated from NHL tumors are functional Treg cells. Hereafter, we refer to them as intratumoral Treg cells.

Figure 3.

CD4+CD25+ T cells from B-cell NHL inhibit cytokine production of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells. (A) A representative ELISPOT image of IFN-γ and IL-4 secretion by an unsorted cell suspension and by CD4+ T cells isolated from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL. (B) Bar graph showing the average number (± SE; n = 6) of IFN-γ and IL-4 spot-forming cells (SFCs) produced by 5 × 105 unsorted, CD4+ or non-CD4+ cells on PHA stimulation. (C) IFN-γ and IL-4 production by CD4+CD25- T cells determined by intracellular staining. IFN-γ- or IL-4-positive cells were determined by gating on the corresponding isotype control. (D) Bar graph showing the average number (± SE; n = 6) of IFN-γ and IL-4 SFCs produced by 5 × 105 total CD4+CD25- T cells incubated with or without CD4+CD25+ T cells on PHA stimulation. Significantly greater IFN-γ secretion (*P < .05) and IL-4 secretion (#P < .01) was seen when compared with cells incubated in the presence of Treg cells. Patient sample nos. 5 to 10 were used in these experiments.

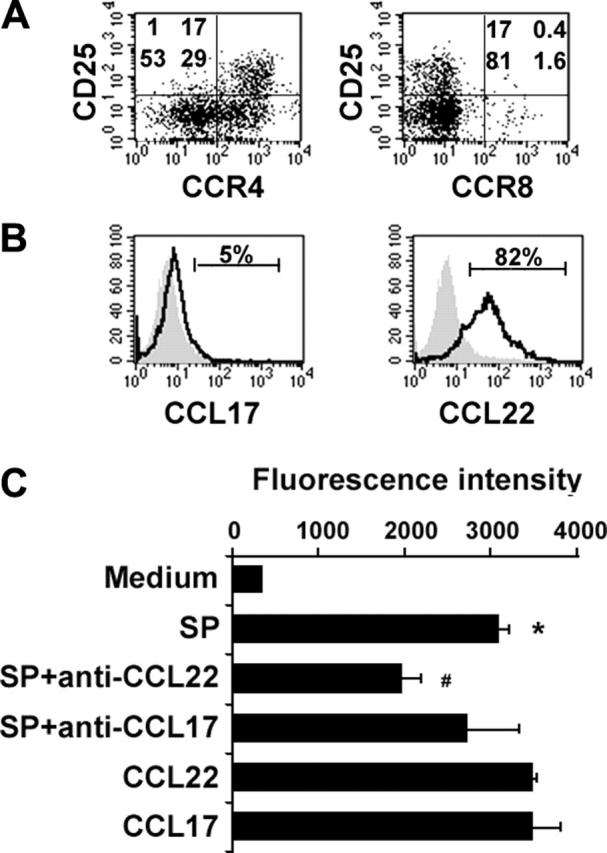

CCL22 from lymphoma B cells attracts Treg cells into the tumor sites of B-cell NHL

To explore mechanisms by which Treg cells might migrate into tumor sites, we examined the expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 on intratumoral Treg cells (Figure 4A), as well as their ligands CCL17 and CCL22 in CD20+ lymphoma B cells from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL (Figure 4B). It has been shown that human bloodborne Treg cells specifically express CCR4 and CCR8 and respond to CCL22, CCL17, and CCL1.37 Cell suspensions from biopsy specimens of patients with B-cell NHL (n = 6) were stained with multicolor antibodies, including surface markers CD3, CD4, CD25, and CD19, chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8, as well as intracellular chemokines CCL17 and CCL22. Cells were analyzed by FACS, and isotype controls were done for each sample. Figure 4A shows a representative specimen with gating on CD3+CD4+ cells. The vast majority of intratumoral Treg cells (94%) expressed CCR4 on their surface, whereas less than half of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells were CCR4+ cells. Neither Treg cells nor CD4+CD25- T cells expressed CCR8 on their surface, which is different from previous reports.35,37 We also determined the expression of intracellular CCL17 and CCL22 in CD20+ cells in biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL. CD20+ lymphoma B cells expressed a significantly high level of CCL22 but did not express CCL17 (Figure 4B, n = 6). Our results suggest that expression of CCL22 by malignant cells may recruit Treg cells to the tumor, resulting in increased Treg cell numbers and suppression of CD4+ T-cell function.

Figure 4.

The interaction between CCL22 and CCR4 is involved in the migration of CD4+CD25+ T cells to tumor sites of B-cell NHL. (A) Dot plots showing the expression of CCR4 and CCR8 on CD4+ T cells from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL (n = 6). (B) Histograms showing intracellular expression of CCL17 and CCL22 in CD20+ lymphoma B cells from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL (n = 6). The shaded histogram represents the isotype control staining, and the open histogram represents the CCL17 or CCL22 staining. (C) The bar graph showing CD4+CD25+ T-cell migration in response to supernatant of lymphoma B cells (SP). CD4+CD25+ T cells were labeled with calcein AM, and the fluorescence intensity of migrated cells was measured by fluorescent plate reader. Results are the mean ± SD, n = 6, *P < .01, compared with media alone; #P < .05, compared with supernatant. Patient sample nos. 3, 10, 11, 16, 17, and 20 to 23 were used in these experiments.

We next measured the chemotaxis and migration of intratumoral Treg cells in response to culture supernatant of lymphoma B cells. The CD20+ lymphoma B cells were cultured for 48 hours, and culture supernatants were collected and served as chemoattractants. Purified CCL17 and CCL22 proteins were used as positive controls. Anti-CCL17 and CCL22 antibodies were added into the supernatants to block CCL17- or CCL22-mediated chemotaxis. As shown in Figure 4C, culture supernatant of CD20+ lymphoma B cells induced significant chemotaxis and migration of Treg cells compared with media alone (n = 6, P < .01). Neutralizing anti-CCL22 antibody, but not anti-CCL17, significantly attenuated Treg cell chemotaxis and migration induced by the culture supernatant of CD20+ lymphoma B cells (n = 6, P < .05). Addition of recombinant CCL22 and CCL17 induced Treg cell chemotaxis and migration. In summary, these results suggest that CCL22 secreted from lymphoma B cells induces migration of CCR4+ Treg cells and may in part account for the increased numbers of Treg cells in B-cell NHL.

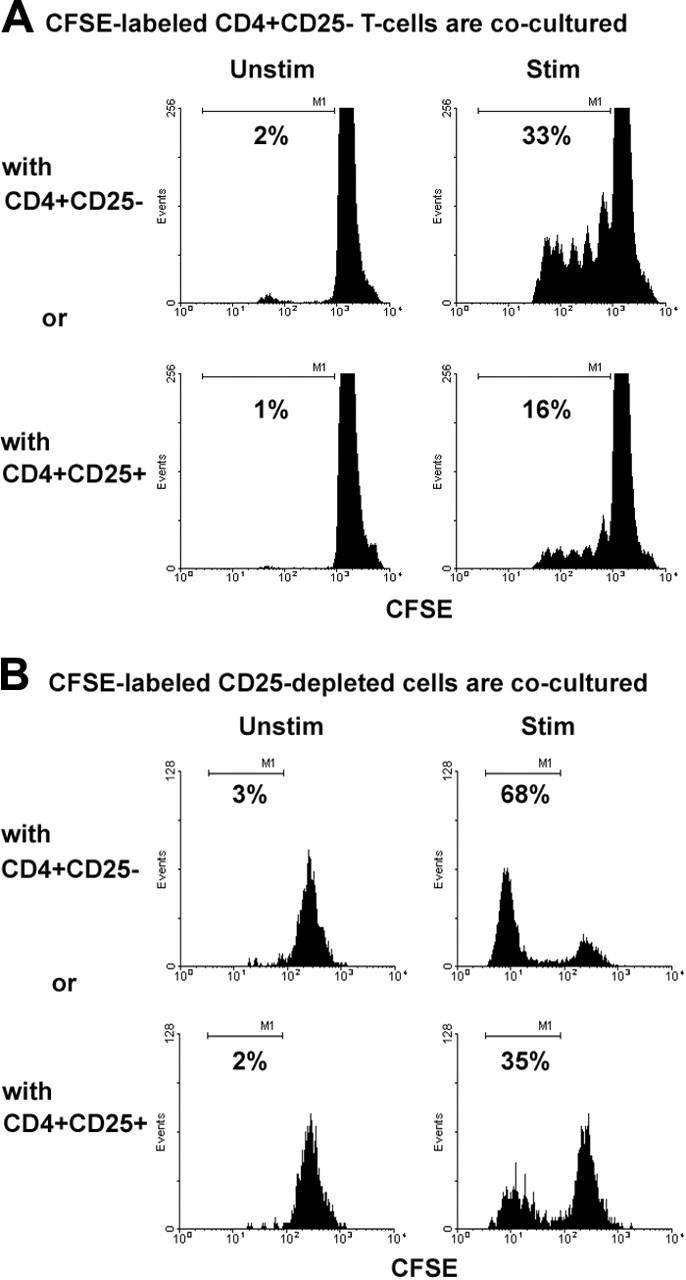

Expression of B7-H1 and PD-1 on infiltrating CD4+CD25+/- T cells in B-cell NHL

B7-H1 (PD-L1) is a member of the B7 superfamily and has been shown to down-regulate T-cell activation through receptor PD-1. B7-H1 is expressed on monocytes or dendritic cells, whereas PD-1 is transcriptionally induced in activated T cells and B cells. However, B7-H1 can also be induced in activated T cells.38 To explore the role of B7-H1 on Treg cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating T cells in B-cell NHL, we determined the expression of B7-H1 and PD-1 on CD4+CD25+/- T cells from biopsy specimens in patients with B-cell NHL. Cell suspensions were analyzed by FACS with multicolor staining and gating on CD3+CD4+ populations. By FACS, PD-1 was consistently expressed on a subset of CD3+CD4+ T cells (n = 6). When we looked at PD-1 expression in the CD4+CD25+ and CD4+CD25- populations, we saw PD-1 expression on the CD4+CD25- subset, but not on Treg cells (Figure 5A). Next, we determined the expression of B7-H1 on resting and activated Treg cells isolated from biopsy specimens of B-cell NHL. Compared with isotype controls, a slight increase of B7-H1 expression could be seen in resting Treg cells. However, on activation with PHA (2.5 μg/mL), B7-H1 expression was remarkably induced in Treg cells (Figure 5B).

Figure 5.

The interaction between PD-1 and B7-H1 is involved in intratumoral Treg cell-mediated inhibition of CD4+CD25+ T cells in B-cell NHL. (A) Dot plots showing the expression of B7-H1 and PD-1 on tumor-infiltrating CD4+CD25+/- T cells freshly isolated from B-cell NHL (n = 6). (B) Dot plots showing the expression of B7-H1 on resting (middle) or PHA-activated (right) CD4+CD25+ T cells (n = 3). (C) Histograms showing the effect of the interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1 on intratumoral Treg cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL. CFSE-labeled CD4+CD25- T cells were cocultured either with CD4+CD25- or CD4+CD25+ T cells in the presence or absence of PHA stimulation for 5 days. Cells in the coculture system were treated with an anti-B7-H1 antibody or PD-1 fusion protein as well as their corresponding controls. The histogram is a representative of 7 samples using the B7-H1 antibody, and of 5 samples using PD-1 Fc. Patient sample no. 11, nos. 15 to 18, and nos. 20 to 23 were used in these experiments.

B7-H1/PD-1 interaction is involved in Treg cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL

Because we found that PD-1 was constitutively expressed on infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells and B7-H1 could be induced on activated intratumoral Treg cells, we explored whether B7-H1/PD-1 interaction was involved in Treg cell-mediated suppression of infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL. CD4+CD25- T cells (responding cells) were labeled with CFSE and cocultured with CD4+CD25+/- T cells (stimulating cells) in the presence or absence of PHA. Anti-B7-H1 antibody or PD-1 fusion protein was added to the PHA-activated coculture well. Anti-human IgG antibody (sodium azide free, 5 μg/mL) or human IgG (5 μg/mL) were used as controls for anti-B7-H1 or PD-1 Fc, respectively. As shown in Figure 5C, the CFSEdim population is the proliferating cell population and was used to measure the proliferation magnitude of CD4+CD25- T cells. As expected, in the presence of intratumoral Treg cells, the number of CFSEdim CD4+CD25- T cells declined on stimulation with PHA compared with the number of CFSEdim T cells in the presence of CD4+CD25- T cells (18% versus 32%). Furthermore, addition of the anti-B7-H1 antibody or PD-1 Fc increased the proliferation of CD4+CD25- T cells compared with their respective isotype controls when cocultured with intratumoral Treg cells (the number of CFSEdim CD4+CD25- T cells 17% versus 23% for anti-B7-H1 compared with 17% versus 24% for PD-1 Fc). This result indicated that blocking the interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1 partly attenuates Treg cell-mediated inhibition of CD4+CD25- T cells.

Discussion

Tumors have a unique microenvironment that may contain cells that target the malignant clone, but may also contain cells that support and promote tumor progression. Little is currently known about the role of infiltrating immune cells in B-cell NHL. Some studies have suggested that increased intratumoral cells are associated with a better outcome, whereas others have suggested that infiltrating T cells are important in lymphomagenesis. This remains an area of some controversy. In the present study, we investigated the role of intratumoral Treg cells in suppressing tumor-infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells in B-cell NHL.

We first quantified the frequencies of CD4+CD25+ T cells present in the tumor site of B-cell NHL. We found a significantly higher percentage of CD4+CD25+ T cells (an average of 17% of the total infiltrating CD4+ T cells) present in biopsy specimens from B-cell NHL compared with tumor-free lymph nodes (6%) and normal PBMCs (7%). The percentage of CD4+CD25+ T cells seen in normal tissue in our study was similar to the percentages reported in the literature.7-10 These CD4+CD25+ T cells are memory T cell-like and express intracellular CTLA-4 and Foxp3. HLA-II was not exclusively expressed on these cells and correlated with activation status rather than with suppressive activity.

CD25 expression is the key feature, but is not specific, for CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. Therefore, CD25 expression alone is not enough to distinguish CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from activated CD4+ T cells because of its inducibility in all subsets of T cells. It has been accepted that expression of transcription factor Foxp3 is confined to CD4+CD25+ Treg cells and critical to development and functional properties of CD4+CD25+ Treg cells. In humans, high levels of CD4+CD25+ T cells have been identified in lung,33 gastric and esophageal cancers,31 ovarian,29,35 breast, and pancreatic tumor specimens,30 as well as Hodgkin lymphoma.36,39 This is the first report that high levels of CD4+CD25+ T cells with a similar phenotype of Treg cells are present in tumor specimens of B-cell NHL. The consequence of these overrepresented CD4+CD25+ T cells in tumor sites of B-cell NHL remains unknown. In the solid tumors, it has been suggested that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells are involved in the mediation of antitumor immunity by suppressing tumor-specific T-cell immunity and thereby contribute to growth of human tumors. However, in Hodgkin lymphoma, the proportion of infiltrating Foxp3+ cells is found to be a positive prognostic factor for patients.36

Similar to Treg cells from PBMCs of healthy individuals, intratumoral CD4+CD25+ T cells from B-cell NHL displayed the ability to suppress autologous infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells. Coculture with CD4+CD25+ T cells significantly decreased the proliferation of PHA-activated infiltrating CD4+CD25- T cells from B-cell NHL. Additionally, CD25 depletion markedly enhanced the proliferation of PHA-activated infiltrating CD4+ T cells in B-cell NHL. Combined with findings of surface CD25 and intracellular CTLA-4 and Foxp3 expression in these infiltrating CD4+ T cells, the suppressive effects of the CD4+CD25+ cells on other intratumoral T cells are consistent with intratumoral Treg cells. Our results showed that the proliferating T cells exhibit an identical number of cell divisions with or without intratumoral Treg cells, suggesting that intratumoral Treg cells suppress the proliferation of some CD4+CD25- T cells but not others. In addition to suppressing proliferation, these intratumoral Treg cells also inhibit the production of IFN-γ and IL-4 by CD4+CD25- T cells, which is consistent with other reports.34,40 The results provide evidence that intratumoral Treg cells play a role in tumor microenvironment of B-cell NHL.

We observed that Treg cells were overrepresented in tumor sites of B-cell NHL. This raised the question whether these cells could be recruited from the circulation. We therefore determined whether intratumoral Treg cells were attracted to the microenvironment of B-cell NHL and what chemokines and chemokine receptors were involved in the chemotaxis of these intratumoral Treg cells. Our results show that intratumoral Treg cells expressed the chemokine receptor CCR4, but not CCR8. Also, lymphoma B cells expressed significantly high levels of intracellular chemokine CCL22, but not CCL17, which is consistent with previous reports but previously undescribed in B-cell NHL. It has been previously reported that human bloodborne Treg cells specifically express CCR4 and CCR8 and respond to CCL22, CCL17, and CCL1.37 Our data showed that CCR4+ intratumoral Treg cells were attracted in vitro by supernatant from cultured lymphoma B cells and CCL22 secreted by these malignant B cells is involved in chemotaxis and migration of intratumoral Treg cells to tumor sites. Although it cannot be excluded that overrepresentation of intratumoral Treg cells may be due to increased local antigen stimulation, our data indicated that malignant lymphoma B cells are in part responsible for overrepresentation of intratumoral Treg cells through the recruitment and, perhaps, subsequently expansion of intratumoral Treg cells.

The underlying mechanisms of Treg cell-mediated suppression are poorly understood, whereas the functional properties of Treg cells are more completely studied. Because cell contact is necessary for Treg cell-mediated suppression, molecules expressed on the cell surface with the ability to down-regulate function (such as CTLA-4, membrane-bound TGF-β, or GITR) are more likely to play an important role in this process.18-21,41-44 A recently described B7 family member, B7-H1, interacting with its receptor PD-1, has been shown to negatively regulate TCR signaling and decrease TCR-mediated proliferation and cytokine production. We observed that PD-1 was specifically expressed on infiltrating CD4+CD25-, but not CD4+CD25+ T cells, and B7-H1 could be induced on activated intratumoral Treg cells in B-cell NHL. This strongly suggests a role for B7-H1 and PD-1 interaction in intratumoral Treg cell-mediated suppression. In fact, our results have indicated that the blockade of interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1 partly attenuates Treg cell-mediated inhibition of CD4+CD25- T cells in tumor sites of B-cell NHL. However, it is unlikely that the interaction between B7-H1 and PD-1 exclusively accounts for the suppressive activity of intratumoral Treg cells in B-cell NHL. Other mechanisms, such as TGF-β, NFATc2 and NFATc3, CTLA4, and possibly even cytokines, may also be involved in the inhibitory action of intratumoral Treg cells in B-cell NHL.

These observations have provided the conceptual framework for us to propose an important role for Treg cells in the regulation of malignant lymphoma B-cell growth. On the one hand, intratumoral Treg cells may have an indirect effect on growth of malignant lymphoma B cells by suppressing tumor-infiltrating helper and effector T helper cells as demonstrated by our current data. On the other hand, Treg cells may have direct effect on growth of malignant lymphoma B cells because it has been shown that CD4+CD25+ Treg cells directly inhibit B-cell activation in vitro and humoral immune response in vivo.45,46

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, January 10, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3376.

Supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (grants CA92104 and CA97274) and by a translational research grant from the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

- 1.de Jong D. Molecular pathogenesis of follicular lymphoma: a cross talk of genetic and immunologic factors. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23: 6358-6363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drach J, Seidl S, Kaufmann H. Treatment of mantle cell lymphoma: targeting the microenvironment. Expert Rev Anticancer Ther. 2005;5: 477-485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dave SS, Wright G, Tan B, et al. Prediction of survival in follicular lymphoma based on molecular features of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. N Engl J Med. 2004;351: 2159-2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ansell SM, Stenson M, Habermann TM, Jelinek DF, Witzig TE. Cd4+ T-cell immune response to large B-cell non-Hodgkin's lymphoma predicts patient outcome. J Clin Oncol. 2001;19: 720-726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baecher-Allan C, Viglietta V, Hafler DA. Human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Semin Immunol. 2004;16: 89-98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shevach EM. CD4+ CD25+ suppressor T cells: more questions than answers. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2: 389-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maloy KJ, Powrie F. Regulatory T cells in the control of immune pathology. Nat Immunol. 2001;2: 816-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Shimizu J, et al. Immunologic tolerance maintained by CD25+ CD4+ regulatory T cells: their common role in controlling autoimmunity, tumor immunity, and transplantation tolerance. Immunol Rev. 2001; 182: 18-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gavin M, Rudensky A. Control of immune homeostasis by naturally arising regulatory CD4+ T cells. Curr Opin Immunol. 2003;15: 690-696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Piccirillo CA, Shevach EM. Naturally-occurring CD4+CD25+ immunoregulatory T cells: central players in the arena of peripheral tolerance. Semin Immunol. 2004;16: 81-88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curotto de Lafaille MA, Lafaille JJ. CD4(+) regulatory T cells in autoimmunity and allergy. Curr Opin Immunol. 2002;14: 771-778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Control of autoimmunity by naturally arising regulatory CD4+ T cells. Adv Immunol. 2003;81: 331-371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299: 1057-1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4: 330-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khattri R, Cox T, Yasayko SA, Ramsdell F. An essential role for Scurfin in CD4+CD25+ T regulatory cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4: 337-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dieckmann D, Bruett CH, Ploettner H, Lutz MB, Schuler G. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory, contact-dependent T cells induce interleukin 10-producing, contact-independent type 1-like regulatory T cells [corrected]. J Exp Med. 2002; 196: 247-253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Kakirman H, Stassen M, Knop J, Enk AH. Infectious tolerance: human CD25(+) regulatory T cells convey suppressor activity to conventional CD4(+) T helper cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196: 255-260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Sartirana C, et al. Human CD25+CD4+ T suppressor cell clones produce transforming growth factor beta, but not interleukin 10, and are distinct from type 1 T regulatory cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196: 1335-1346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Annunziato F, Cosmi L, Liotta F, et al. Phenotype, localization, and mechanism of suppression of CD4(+)CD25(+) human thymocytes. J Exp Med. 2002;196: 379-387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamura K, Kitani A, Strober W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 2001;194: 629-644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Piccirillo CA, Letterio JJ, Thornton AM, et al. CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells can mediate suppressor function in the absence of transforming growth factor beta1 production and responsiveness. J Exp Med. 2002;196: 237-246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sakaguchi S, Sakaguchi N, Asano M, Itoh M, Toda M. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by activated T cells expressing IL-2 receptor alpha-chains (CD25). Breakdown of a single mechanism of self-tolerance causes various autoimmune diseases. J Immunol. 1995;155: 1151-1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takahashi T, Kuniyasu Y, Toda M, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells: induction of autoimmune disease by breaking their anergic/suppressive state. Int Immunol. 1998;10: 1969-1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itoh M, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi N, et al. Thymus and autoimmunity: production of CD25+CD4+ naturally anergic and suppressive T cells as a key function of the thymus in maintaining immunologic self-tolerance. J Immunol. 1999;162: 5317-5326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McHugh RS, Shevach EM. The role of suppressor T cells in regulation of immune responses. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110: 693-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Onizuka S, Tawara I, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi S, Fujita T, Nakayama E. Tumor rejection by in vivo administration of anti-CD25 (interleukin-2 receptor alpha) monoclonal antibody. Cancer Res. 1999;59: 3128-3133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shimizu J, Yamazaki S, Sakaguchi S. Induction of tumor immunity by removing CD25+CD4+ T cells: a common basis between tumor immunity and autoimmunity. J Immunol. 1999;163: 5211-5218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sutmuller RP, van Duivenvoorde LM, van Elsas A, et al. Synergism of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 blockade and depletion of CD25(+) regulatory T cells in antitumor therapy reveals alternative pathways for suppression of autoreactive cytotoxic T lymphocyte responses. J Exp Med. 2001;194: 823-832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Woo EY, Chu CS, Goletz TJ, et al. Regulatory CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells in tumors from patients with early-stage non-small cell lung cancer and late-stage ovarian cancer. Cancer Res. 2001;61: 4766-4772. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liyanage UK, Moore TT, Joo HG, et al. Prevalence of regulatory T cells is increased in peripheral blood and tumor microenvironment of patients with pancreas or breast adenocarcinoma. J Immunol. 2002;169: 2756-2761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ichihara F, Kono K, Takahashi A, Kawaida H, Sugai H, Fujii H. Increased populations of regulatory T cells in peripheral blood and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with gastric and esophageal cancers. Clin Cancer Res. 2003; 9: 4404-4408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steitz J, Bruck J, Lenz J, Knop J, Tuting T. Depletion of CD25(+) CD4(+) T cells and treatment with tyrosinase-related protein 2-transduced dendritic cells enhance the interferon alpha-induced, CD8(+) T-cell-dependent immune defense of B16 melanoma. Cancer Res. 2001;61: 8643-8646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Woo EY, Yeh H, Chu CS, et al. Cutting edge: regulatory T cells from lung cancer patients directly inhibit autologous T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 2002;168: 4272-4276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Viguier M, Lemaitre F, Verola O, et al. Foxp3 expressing CD4+CD25(high) regulatory T cells are overrepresented in human metastatic melanoma lymph nodes and inhibit the function of infiltrating T cells. J Immunol. 2004;173: 1444-1453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Curiel TJ, Coukos G, Zou L, et al. Specific recruitment of regulatory T cells in ovarian carcinoma fosters immune privilege and predicts reduced survival. Nat Med. 2004;10: 942-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alvaro T, Lejeune M, Salvado MT, et al. Outcome in Hodgkin's lymphoma can be predicted from the presence of accompanying cytotoxic and regulatory T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11: 1467-1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Iellem A, Mariani M, Lang R, et al. Unique chemotactic response profile and specific expression of chemokine receptors CCR4 and CCR8 by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2001;194: 847-853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dong H, Strome SE, Matteson EL, et al. Costimulating aberrant T cell responses by B7-H1 autoantibodies in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Invest. 2003;111: 363-370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Marshall NA, Christie LE, Munro LR, et al. Immunosuppressive regulatory T cells are abundant in the reactive lymphocytes of Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2004;103: 1755-1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasada T, Kimura M, Yoshida Y, Kanai M, Takabayashi A. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with gastrointestinal malignancies: possible involvement of regulatory T cells in disease progression. Cancer. 2003;98: 1089-1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baecher-Allan C, Viglietta V, Hafler DA. Inhibition of human CD4(+)CD25(+high) regulatory T cell function. J Immunol. 2002;169: 6210-6217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamura K, Kitani A, Fuss I, et al. TGF-beta 1 plays an important role in the mechanism of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell activity in both humans and mice. J Immunol. 2004;172: 834-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192: 303-310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Read S, Malmstrom V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192: 295-302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bystry RS, Aluvihare V, Welch KA, Kallikourdis M, Betz AG. B cells and professional APCs recruit regulatory T cells via CCL4. Nat Immunol. 2001; 2: 1126-1132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lim HW, Hillsamer P, Banham AH, Kim CH. Cutting edge: direct suppression of B cells by CD4+ CD25+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2005;175: 4180-4183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]