Abstract

Although TP53 mutations are rare in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), Mdm2 overexpression has been reported as an alternative cause of p53 dysfunction. We investigated the potential therapeutic use of nongenotoxic p53 activation by a small-molecule antagonist of Mdm2, Nutlin-3a, in CLL. Nutlin-3a induced significant apoptosis in 30 (91%) of 33 samples from previously untreated patients with CLL; all resistant samples had TP53 mutations. Low levels of Atm (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) or high levels of Mdm2 (murine double minute 2) did not prevent Nutlin-3a from inducing apoptosis. Nutlin-3a used transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways to induce p53-mediated apoptosis. Predominant activation of the transcription-independent pathway induced more pronounced apoptosis than that of the transcription-dependent pathway, suggesting that activation of the transcription-independent pathway is sufficient to initiate p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL. Combination treatment of Nutlin-3a and fludarabine synergistically increased p53 levels, and induced conformational change of Bax and apoptosis in wild-type p53 cells but not in cells with mutant p53. The synergistic apoptotic effect was maintained in samples with low Atm that were fludarabine resistant. Results suggest that the nongenotoxic activation of p53 by targeting the Mdm2-p53 interaction provides a novel therapeutic strategy for CLL.

Introduction

B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) accounts for 25% of all leukemias and is the most common form of lymphoid malignancy in Western countries.1 Treatment with the purine analog fludarabine, which is the current standard therapy for CLL, has been shown to increase the complete remission rate, enhance progression-free survival, and increase the median duration of the clinical response but not the survival in previously untreated patients with CLL, compared with treatment with chlorambucil alone or combination chemotherapy.2-4 Although the introduction of fludarabine-based combination regimens has improved the overall success of CLL treatment,5,6 identification of novel therapies for CLL remains a high priority.

CLL is characterized by the accumulation of long-lived CD5+ B lymphocytes that show resistance to apoptosis. The triphosphate of fludarabine is incorporated into the DNA of the quiescent CLL cells during repair DNA synthesis and induces DNA damage.7-9 The DNA strand breaks can lead to the activation of p53 and p53-dependent target genes,10,11 and it has been suggested that p53-mediated induction of apoptosis primarily contributes to fludarabine-induced killing of CLL cells in vivo.11,12 It has also been reported that fludarabine can induce apoptosis of CLL cells in vitro in a p53-independent fashion,13,14 although the in vivo significance remains unknown.11,12 Clinically, the presence of p53 mutations in CLL cells is associated with decreased survival and resistance to fludarabine treatment.15-17

Although TP53 mutations occur in only 5% to 10% of patients with CLL,18 an alternative mechanism of inactivation of the p53 pathway, inactivation of the ATM (ataxia telangiectasia mutated) gene, has been reported.19 Atm binds directly to p53 and is responsible for phosphorylation of p53, thereby contributing to the activation and stabilization of p53 during ionizing radiation–induced DNA damage response.20,21 Total or partial inactivation of Atm protein expression has been observed in 20% to 40% of CLL patients, and ATM mutations have been demonstrated in a substantial proportion of such cases.22,23 Some authors have postulated that in patients with low Atm levels, p53 may not be sufficiently activated for induction of apoptosis in response to DNA-damaging agents.19 Mdm2 overexpression has been reported to be a potential cause of p53 dysfunction in CLL.24,25 Mdm2, a p53-specific E3 ubiquitin ligase, is a principal cellular antagonist of p53 and mediates the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of p53.26 Mdm2, which can enhance tumorigenic potential and resistance to apoptosis, has been reported to be overexpressed in 50% to 70% of patients with CLL.24,25 However, the impact of Mdm2 overexpression on p53 dysfunction remains controversial, and a recent study has suggested that p53 activation in CLL cells is largely unaffected by variations in basal levels of Mdm2.19

Nutlins are potent and selective small-molecule antagonists of Mdm2 that bind Mdm2 in the p53-binding pocket and activate the p53 pathway in cells with wild-type p53.27 Recently, we have reported that Nutlins efficiently induce p53-dependent apoptosis in acute myeloid leukemia (AML) cells that harbor wild-type p53 and that high levels of Mdm2 overexpression in AML cells were associated with higher susceptibility to Nutlin-induced apoptosis.28 It has also been described that Nutlins can activate p53 signaling independently of phosphorylation of p53.29 It is therefore possible that Nutlins can overcome functional p53 inactivation associated with Mdm2 overexpression or Atm deficiency in CLL. p53 has transcription-dependent and transcription-independent proapoptotic activities. p53 transcriptionally induces the proapoptotic BH3-only proteins Noxa and Puma, which indirectly promote Bax/Bak activation by inhibiting the functions of antiapoptotic Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL.30 p53 can also trigger mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization and apoptosis in the absence of transcription, through direct activation of Bax or Bak or through binding to Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL.30 We have shown that both transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways are operational in p53-dependent apoptosis in AML.28 However, the quantitative contribution of transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways to total p53-mediated apoptosis remains unclear.

In this study, we investigated the potential therapeutic use of p53 activation by Mdm2 antagonists in CLL. We found that (1) Mdm2 inhibition efficiently induces p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL cells independent of Mdm2 or Atm expression levels, (2) transcription-dependent apoptosis may not always be the major mode by which p53 induces apoptosis and that the exclusive activation of the transcription-independent pathway can fully induce apoptosis, and (3) Nutlin-3a and fludarabine synergistically induce p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL cells, which may overcome fludarabine resistance in CLL.

Materials and methods

Reagents

The selective small-molecule antagonist of MDM2, Nutlin-3a (kindly provided by Dr Lyubomir T. Vassilev, Hoffmann-La Roche, Nutley, NJ),27 and 9-β-d-arabinofuranosyl-2-fluoroadenine (F-ara-A, fludarabine) were used. In some experiments, cells were cultured with 3.5 μM cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) or 200 μM Z-VAD-FMK (Alexis, San Diego, CA). Cycloheximide and Z-VAD-FMK were added to the cells 1 hour before drug administration. The final dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) concentration in the medium did not exceed 0.1% (vol/vol). At this concentration, DMSO itself did not induce apoptosis up to 72 hours in primary CLL cells.

Primary samples and cell cultures

Heparinized peripheral-blood samples were obtained from previously untreated CLL patients with more than 70% malignant cells after informed consent, in accordance with institutional guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki. Mononuclear cells were purified by Ficoll-Hypaque (Sigma Chemical, St Louis, MO) density-gradient centrifugation, and nonadherent cells were resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 10% FCS at a density of 5 × 105 cell/mL. Cells were treated with Nutlin-3a or F-ara-A, both at 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM, and were incubated for 72 hours at 37°C and 5% CO2 in a humidified atmosphere. In the combination experiments of Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A, the 2 agents were added simultaneously to cells at a fixed-concentration ratio (1:1) and the cells were incubated for 72 hours.

Apoptosis analysis

Evaluation of apoptosis by the annexin V–propidium iodide (PI) binding assay was performed as described.28 The extent of apoptosis was quantified as percentage of annexin V–positive cells, and the extent of drug-specific apoptosis was assessed by the following formula: percent specific apoptosis = (test – control) × 100/(100 – control). In the formula, the numerator is the actual amount of killing that occurred, and the denominator is the potential amount of killing that could occur. To measure mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm), cells were loaded with MitoTracker Red CMXRos (300 nM) and MitoTracker Green (100 μM; both from Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) for 1 hour at 37°C. The ΔΨm was then assessed by measuring CMXRos retention (red fluorescence) while simultaneously adjusting for mitochondrial mass (green fluorescence).

Western blot analysis

Western blot analysis was performed as previously described.28 The following antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal anti-p53 (FL-393; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA); mouse monoclonal anti–phospho-p53 (Ser15, 16G8; Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA); mouse monoclonal anti-Mdm2 (D-12; Santa Cruz Biotechnology); rabbit polyclonal anti-Puma (Ab-1; EMD Biosciences, San Diego, CA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Bax (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); rabbit polyclonal anti-Atm (Ab-3; Oncogene Research, Cambridge, MA); and mouse monoclonal anti–β-actin (AC-74; Sigma Chemical).

Quantitation of intracellular protein by flow cytometry

For intracellular p53 detection, cells were fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, permeabilized with 100% ice-cold methanol, and incubated for 1 hour at 4°C with fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)–conjugated antibody against p53 or its isotypic control (FITC-conjugated p53 antibody reagent set; BD Biosciences). Involvement of Bax conformational change was analyzed by means of an antibody directed against the NH2-terminal region of Bax (YTH-6A7; Trevigen, Gaithersburg, MD).31 Cellular fixation, permeabilization, and staining with primary antibody or an isotypic control were performed using the Dako IntraStain kit (Dako Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. After washing, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 chicken antimouse secondary antibodies (Molecular Probes) for 30 minutes at 4°C.

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopy

Immunofluorescence and confocal microscopic examination were performed as previously described,28 with minor modification. Cells were washed twice with PBS, fixed with 2% paraformaldehyde, and permeabilized with ice-cold 100% methanol. The cells were blocked in 5% normal goat serum for 30 minutes, followed by incubation overnight at 4°C with rabbit polyclonal anti-p53 antibodies FL-393 (1:100 vol/vol; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and mouse monoclonal anti–cytochrome c oxidase IV (10G8, 1 μg/mL; Molecular Probes). After washing, cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488 chicken antirabbit secondary antibody and Alexa Fluor 594 chicken antimouse secondary antibody (Molecular Probes) diluted in 5% normal goat serum for 30 minutes at 4°C. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole). Images were obtained using a 60 × /1.40 PlanApo objective lens on an Olympus FV500 confocal microscope with Fluoview version 4.3 software (Olympus, Melville, NY).

Reverse-transcription–polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) and DNA sequencing of p53

Based on the low incidence of p53 mutation and reported association between p53 status and cell response to Nutlins,27,28,32 sequence analysis of p53 was performed in Nutlin-resistant cases and in selected Nutlin-sensitive cases. The methodology was previously described.28

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using the 2-tailed Student t test and the Pearson correlation coefficient. Statistical significance was considered when P values were less than .05. Unless otherwise indicated, average values were expressed as mean plus or minus SEM. Synergism, additive effects, and antagonism were assessed as previously described.28 The combination index (CI), a numeric description of combination effects, was calculated using the more stringent statistical assumption of mutually nonexclusive modes of action. When CI = 1, this equation represents the conservation isobologram and indicates additive effects. CI values less than 1.0 indicate a more than expected additive effect (synergism), while CI values more than 1.0 indicate antagonism between the 2 drugs.

Results

Nutlin-3a induces apoptosis, which is enhanced by combination with F-ara-A, in CLL cells

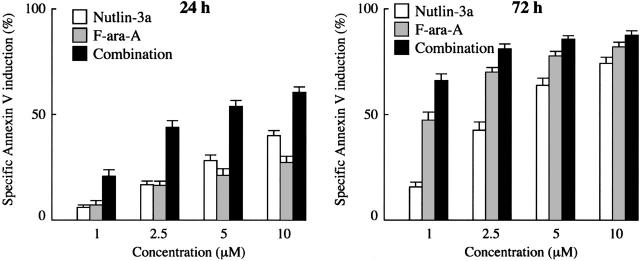

First, we examined the apoptotic effect of the Mdm2 inhibitor on primary cells from 33 patients with CLL. The patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Spontaneous apoptosis as determined by annexin V positivity in the series was 15.0% ± 1.5% (range, 2.1%-36.2%) at 24 hours and 25.9% ± 2.4% (range, 1.6%-48.5%) at 72 hours. Cells from 30 cases showed more than 30% increase in the proportion of annexin V–binding cells after 72-hour treatment with 10 μM Nutlin-3a. The residual 3 cases showed a minimal increase in the proportion of annexin V–binding cells even after 72-hour exposure to 10 μM Nutlin-3a (4%-8% specific apoptosis), and were found to have mutant p53 (TCC>TTC; S127F in patient no. 2, AGT>GGT; S115G in patient no. 28 and CGA>TGA; R123X in patient no. 33). The close relation between p53 status of cells and apoptotic sensitivity to Nutlins has been already established.27,28,32 Treatment of the 30 primary CLL samples with Nutlin-3a caused a dose- and time-dependent increase in the percentage of annexin V–positive cells (Figure 1). The percentages of cells undergoing specific apoptosis at 24 hours after exposure to 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM Nutlin-3a were 6.3% ± 1.1%, 16.8% ± 2.1%, 28.6% ± 2.5%, and 40.1% ± 2.5%, respectively, and 15.4% ± 2.2%, 42.7% ± 3.6%, 64.2% ± 3.2%, and 74.3% ± 2.8% after 72 hours, respectively. CLL cells were also treated with F-ara-A, and annexin V–positive fractions were determined. F-ara-A also induced apoptosis in 30 Nutlin-sensitive samples in a dose- and time-dependent manner (Figure 1). The percentages of specific apoptosis at 24 hours after exposure to 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM F-ara-A were 7.8% ± 1.9%, 16.2% ± 2.5%, 21.5% ± 2.8%, and 27.8% ± 3.1%, respectively, and increased to 46.8% ± 3.9%, 70.2% ± 2.1%, 77.9% ± 2.0%, and 82.5% ± 1.7% after 72-hour exposure, respectively. Results in 3 mutant p53 cases were intriguing: these Nutlin-resistant samples were also resistant to F-ara-A–induced apoptosis at 24 hours, with only 0% to 5% specific apoptosis after exposure to 10 μM F-ara-A. The percentages sharply contrasted with those in Nutlin-sensitive cases (2.3% ± 1.4% versus 27.8% ± 3.1%; P < .05), implying that the apoptotic activity of F-ara-A in the early time period largely depends on the p53 pathway. The percentages increased to some extent at 72 hours (23%-34%), though they were significantly lower compared with Nutlin-sensitive cases (29.6% ± 3.4% versus 82.5% ± 1.7%; P < .01). This delayed induction of apoptosis by F-ara-A in mutant p53 cases may reflect its p53-independent apoptotic activity.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| No. of patients | 33 |

| Median age, y (range) | 60 (42-80) |

| Sex, male/female, no. of patients | 21/12 |

| Rai stages, no. of patients | |

| 0 to II | 28 |

| III to IV | 5 |

Figure 1.

Treatment of primary CLL samples with Nutlin-3a or F-ara-A causes dose- and time-dependent apoptosis, and their combination shows synergistic effects. Cells from 30 Nutlin-sensitive samples were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Nutlin-3a or F-ara-A, and the annexin V–positive fractions were measured by flow cytometry at 24 and 72 hours. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

To determine the combined effects of Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A, we exposed cells from 30 Nutlin-sensitive samples to Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A (0, 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM), using a fixed-ratio (1:1) experimental design. The percentages of specific apoptosis in the combination treatment group at the concentration of 1, 2.5, 5, and 10 μM were 21.0% ± 3.2%, 44.0% ± 3.2%, 54.0% ± 2.8%, and 60.6% ± 2.7% after 24-hour incubation, respectively, and increased at 72 hours to 65.9% ± 3.0%, 81.1% ± 2.2%, 85.7% ± 1.8%, and 88.1% ± 1.7%, respectively (Figure 1). Based on the range of apoptotic effects (21.0%-60.6% at 24 hours and 65.9%-85.7% at 72 hours in the combination treatment group), the CI values for ED50 and ED75 were considered to directly reflect their combination effect at 24 and 72 hours, respectively. The CI values were 0.50 for ED50 at 24 hours and 0.66 for ED75 at 72 hours, indicating a synergistic interaction of Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A in induction of apoptosis (Table 2). At 72 hours, the apoptotic effects of F-ara-A or of the Nutlin-3a/F-ara-A combination appeared to reach their maximums at 2.5 μM (Figure 1), a finding that might explain the relatively high CI value (1.39) for ED90 at 72 hours. The averaged CI values were also calculated from the values for ED50, ED75, and ED90, and were 0.65 at 24 hours and 0.81 at 72 hours. The CI value for ED50 at 24 hours was individually calculated in 23 cases in which the maximal percentage of specific apoptosis exceeded 50%. The CI values for ED50 ranged from 0.1 to 1.3 (median, 0.63) and were less than 1.0 in 19 (83%) of the 23 cases. These findings suggest that Nutlin-3a synergizes with F-ara-A to induce apoptosis in CLL cells.

Table 2.

Combination index values for apoptotic effects of F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a

| ED50 | ED75 | ED90 | Averaged Cl* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| At 24 h | 0.50 | 0.63 | 0.82 | 0.65 |

| At 72 h | 0.36 | 0.66 | 1.39 | 0.81 |

The averaged combination index (Cl) values were calculated from the ED50, ED75, and ED90.

Early stage of apoptosis induction by F-ara-A in CLL cells in vitro is p53 dependent

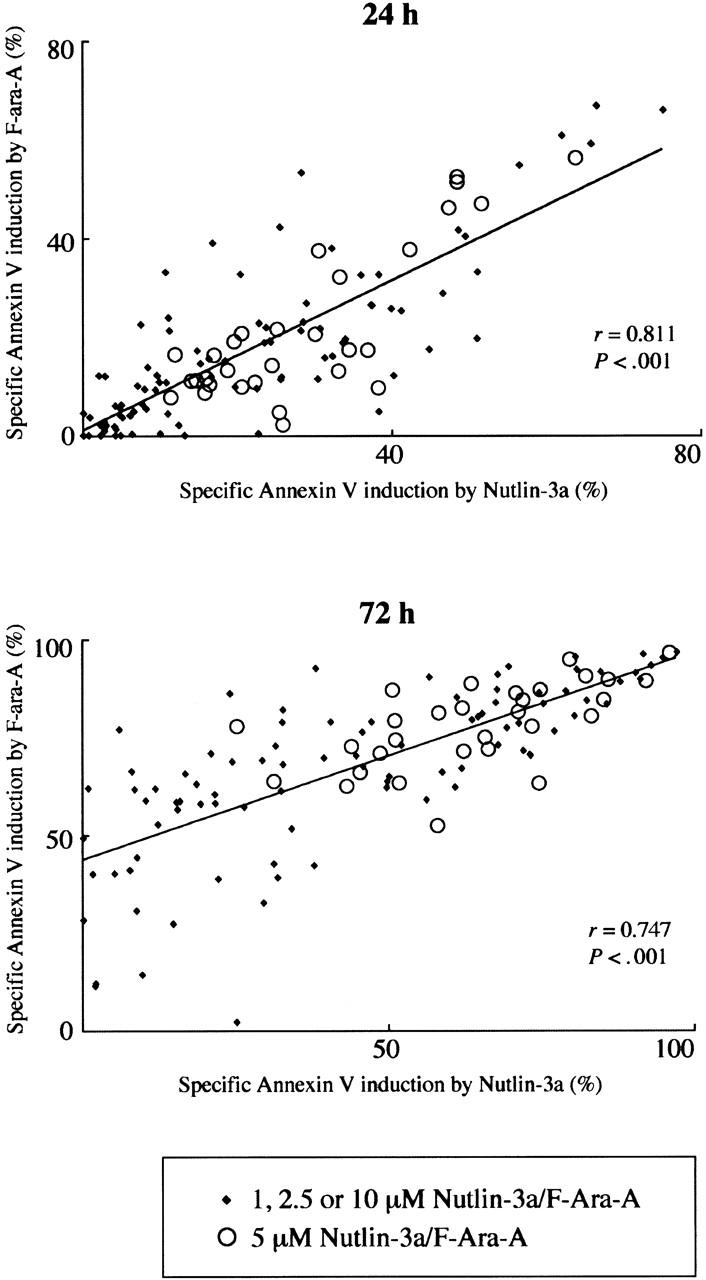

Fludarabine has been shown to depend on p53-mediated induction of apoptosis for its cytotoxicity in vivo, but the extent of contribution of p53 signaling to the total apoptotic potential of fludarabine in vitro remains unknown.11-14 We correlated the extent of apoptosis induced by 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM Nutlin-3a with that induced by the same molar concentration of F-ara-A. The levels of F-ara-A–induced apoptosis directly correlated (r = 0.811; P < .001) with these induced by Nutlin-3a at 24 hours (Figure 2). It is unlikely that the strong correlation merely reflects similar dose-response curves between Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A, since the direct correlation was seen in each specific concentration group where the apoptotic response to treatment widely differed among samples (Figure 2). A positive correlation of F-ara-A–induced apoptosis levels with those induced by Nutlin-3a was also seen at 72 hours (r = 0.747; P < .001) (Figure 2). Of interest, the Y-intercept value of the regression line generated from 72-hour data was 0.43, which sharply contrasts with the nearly equal zero value (0.0097) at 24 hours. Considering the specific activation of p53 signaling in Nutlin-3a–treated cells,27,28 diverse susceptibilities of cell samples to Nutlin-induced apoptosis, and the p53-independent apoptogenic activity of F-ara-A at 72 hours in mutant p53 cases, it seems likely that F-ara-A primarily induces p53-dependent apoptosis in the first 24 hours and later shows p53-dependent and p53-independent activities.

Figure 2.

Positive correlation of Nutlin-3a– and F-ara-A–induced apoptosis in CLL patient samples. The extent of apoptosis induced by 1, 2.5, 5, or 10 μM Nutlin-3a was correlated with that induced by the same molar concentration of F-ara-A in 30 Nutlin-sensitive samples.

Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A synergistically induce p53 and activate Bax

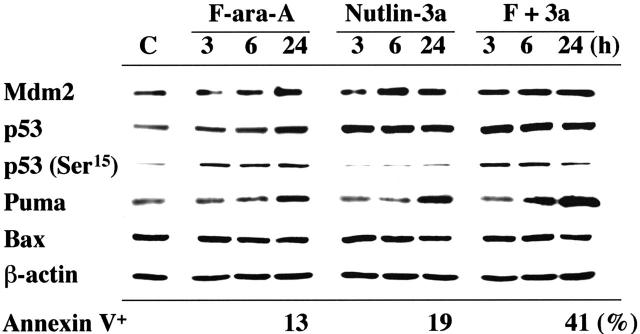

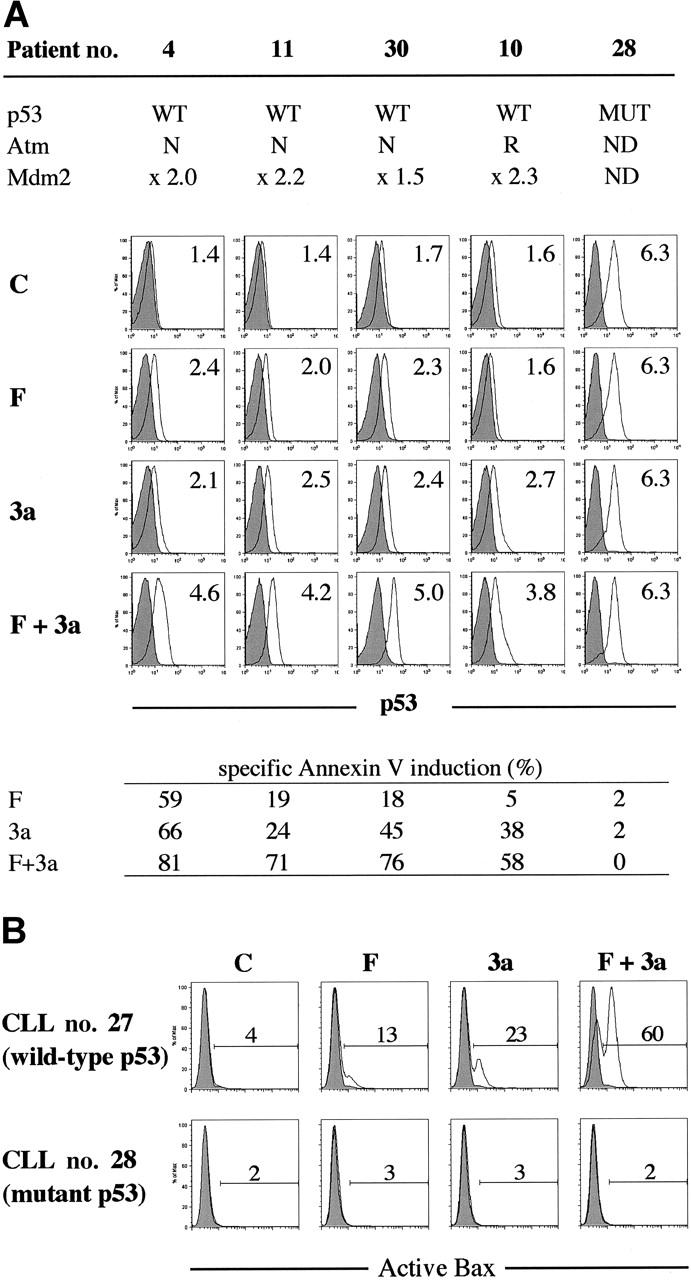

p53 activation in the first 24 hours after F-ara-A treatment was seen in a primary CLL sample with wild-type p53 (patient no. 16), in which p53 phosphorylation at Ser15 and p53 accumulation were detectable at 3 hours after exposure to 5 μM F-ara-A (Figure 3). The F-ara-A–induced p53 levels at 3 and 6 hours were lower than those induced by the same molar concentrations of Nutlin-3a, probably because of the indirect induction of p53 through DNA damage in F-ara-A–treated cells. p53 induction was followed by increased levels of BH3-only protein Puma. PUMA is one of the p53 target genes, and Puma has been shown to be a mediator of p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL.33 Nutlin-3a treatment caused rapid accumulation of p53 that is mostly unphosphorylated at Ser15, followed by Mdm2 and Puma induction. Notably, the degree of Puma induction was more pronounced in cells simultaneously treated with F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a. Bax expression levels did not change significantly. Similar findings were obtained in an additional wild-type p53 sample from patient no. 18. For a more quantitative and sensitive analysis of p53 induction after treatment, p53 levels were measured at the single-cell level in 8 wild-type p53 samples (patients nos. 4, 9-11, 27, and 30-32) and 2 mutant p53 samples (patients nos. 28 and 33) by means of flow cytometry. As shown in Figure 4A, cells treated with 5 μM F-ara-A or 5 μM Nutlin-3a for 24 hours showed mild to moderate increases in p53 levels in samples with wild-type p53. The increase became evident when the 2 compounds were combined, indicating a synergistic induction of p53 by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a. The synergistic effect was also seen in wild-type p53 cases with low Atm levels (patients nos. 9 and 10) but not in mutant p53 cases (patients nos. 28 and 33). Proapoptotic protein Bax is one of the critical mediators of the downstream p53 signaling, and Bax activation is associated with its conformational change.31,34,35 Involvement of Bax conformational change was analyzed in primary samples from patients nos. 27 and 28 by means of a conformation-specific antibody directed against the NH2-terminal region of Bax (clone YTH-6A7). Patient no. 27 had wild-type p53, while patient no. 28 had mutant p53. Cells were preincubated in the presence of 200 μM Z-VAD-FMK prior to the addition of 5 μM F-ara-A, 5 μM Nutlin-3a, or both, to inhibit caspase activation–mediated conformational change of Bax.31,34 As shown in Figure 4B, only a few control cells were positive with this antibody. An increase in the percentage of Bax-positive cells was seen following 24-hour incubation with F-ara-A or Nutlin-3a when compared with control cells only in cases with wild-type p53, indicating that F-ara-A induces Bax conformational change via p53 signaling. Of interest, in a case with wild-type p53, combination treatment induced Bax conformational change in a large proportion of cells, which is in accordance with the synergistic induction of apoptosis and p53 accumulation by simultaneous F-ara-A/Nutlin-3a treatment. Synergistic Bax activation by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a was confirmed in 2 additional wild-type p53 samples from patients nos. 22 and 30. Taken together, p53 plays a central role both in apoptosis induction by F-ara-A alone and in its synergistic action with Nutlin-3a in the early period after exposure.

Figure 3.

Induction of p53-related proteins by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a in a CLL sample with wild-type p53. The sample contained more than 95% CD5+CD19+ cells with normal Atm levels. Cells were treated with 5 μM F-ara-A (F) and 5 μM Nutlin-3a (3a) either as individual agents or in combination, for the indicated times. F-ara-A induced p53 phosphorylation on Ser15, followed by p53 accumulation and Puma induction. Nutlin-3a induced immediate accumulation of p53 that is mostly free of phosphorylation on Ser15, followed by Mdm2 and Puma induction. The degree of Puma induction was further enhanced in cells treated with F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a. β-Actin is used to confirm equal loading of proteins. Lysate from cells before treatment served as control (C).

Figure 4.

Synergistic induction of p53 signaling by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a in CLL cells with wild-type p53. (A) Synergistic induction of p53 by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a in CLL cells with wild-type p53. Samples from 4 wild-type p53 patients (nos. 4, 10, 11, and 30; no. 10 showed reduced Atm expression) and from a mutant p53 patient (no. 28) were treated for 24 hours with 5 μM F-ara-A (F) and 5 μM Nutlin-3a (3a) either as individual agents or in combination. DMSO-treated cells served as control (C). Shaded histograms represent isotype controls. Results show that F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a synergistically induce p53 in cases with wild-type p53, irrespective of Atm status. p53 expression levels were expressed as mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) ratio calculated by the following formula: MFI ratio = (MFI for anti-p53 antibody)/(MFI for isotypic control). WT indicates wild-type; MUT, mutant; N, normal; R, reduced; and ND, not done. (B) A synergistic activation of Bax by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a in CLL cells with wild-type p53. Cells from patient no. 27 (wild-type p53) and from patient no. 28 (mutant p53) were treated for 24 hours with 5 μM F-ara-A (F) and 5 μM Nutlin-3a (3a) either as individual agents or in combination. Bax conformational change was determined by staining with the active conformation-specific anti-Bax antibody YTH-6A7 or a corresponding isotype control (shaded histogram). Z-VAD-FMK (200 μM) was used to inhibit caspase activation–mediated conformational change of Bax, and cells treated with Z-VAD-FMK alone served as control (C). Results show a synergistic activation of Bax by F-ara-A and Nutlin-3a in wild-type p53 but not in mutant p53 cells.

Both transcription-dependent and transcription-independent apoptosis pathways are operational in p53-dependent apoptosis in CLL

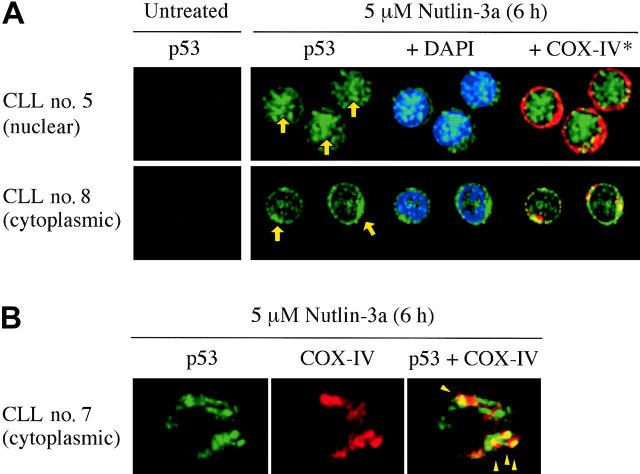

Transcriptional activation of target genes of p53 occurs in the nucleus, while cytoplasmic p53 mediates transcription-independent apoptosis if p53 levels reach a certain threshold.30 We determined the intracellular localization of p53 in 20 Nutlin-sensitive samples using confocal microscopy. In each experiment, 200 cells were examined. A small amount of p53 was diffusely distributed in untreated cells (not shown). After 6-hour treatment with 5 μM Nutlin-3a, individual cells showed either cytoplasmic, cytoplasmic and nuclear, or nuclear accumulation of p53. Of interest, the primary p53 localization patterns were much different from case to case (Figure 5A). Cells showed primary p53 localization to the nucleus (≥ 70% cells showed nuclear accumulation of p53) in 8 samples, primary p53 localization to the cytoplasm (≥ 70% cells showed cytoplasmic accumulation) in 7 samples, and mixed localization pattern (mixture of cells with cytoplasmic or nuclear p53) in the residual 5 samples. Accumulated cytoplasmic p53 partially colocalized with the mitochondrial marker protein cytochrome c oxidase IV (yellow-orange areas in Figure 5B). The percentages of specific annexin V induction at 24 hours after exposure to 5 μM Nutlin-3a were 38.7% ± 6.6% in cells with cytoplasmic localization, 32.8% ± 5.5% with the mixed pattern, and 22.8% ± 3.0% with nuclear localization. Samples with cytoplasmic p53 localization pattern showed a higher percentage of Nutlin-induced apoptosis than those with nuclear pattern (P < .05). For a more quantitative analysis of the relative contribution of transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways, the role of newly synthesized proteins in the initiation of apoptosis was assessed by treatment of cells from 30 Nutlin-sensitive cases with 10 μM Nutlin-3a in the absence or presence of 3.5 μM cycloheximide. In this analysis, we determined loss of ΔΨm to assess the inhibitory effect of cycloheximide on apoptosis because it was more sensitive than annexin V staining in this setting. Treatment of cells with cycloheximide alone showed minimal apoptotic effect (7.3% ± 2.0% specific apoptosis). The inhibitory effect of cycloheximide pretreatment on loss of ΔΨm compared with Nutlin-3a alone varied widely, ranging from 0% to 93% (median effect, 51%). Fifteen of 30 cases showed 50% or less inhibition (transcription-independent apoptosis predominance; transcription-independent group), and the residual 15 cases, more than 50% inhibition (transcription-dependent apoptosis predominance; transcription-dependent group). The percentages of specific annexin V induction at 24 hours after exposure to 5 μM Nutlin-3a were 34.5% ± 3.7% in the transcription-independent group and 22.8% ± 2.6% in the transcription-dependent group, showing a significant difference (P < .05). To see if the difference was attributable to the early timing of analysis, the extent of apoptosis after 72-hour treatment of 5 μM Nutlin-3a was compared between the 2 groups. Again, there was a significant difference in percentages of specific annexin V induction between the transcription-independent group and the transcription-dependent group (72.5% ± 3.1% versus 55.8% ± 4.8%; P < .01). These findings suggest that activation of transcription-independent pathway can sufficiently launch p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL.

Figure 5.

p53 relocation after Nutlin-3a treatment. (A) Representative p53 localization patterns (arrows) in primary CLL cells from patient no. 5 (nuclear accumulation) and no. 8 (cytoplasmic accumulation), which were treated with 5 μM Nutlin-3a for 6 hours. Cells were stained for p53 (green) and mitochondrial marker protein cytochrome c oxidase IV (red) and visualized by confocal microscopy. Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (B) Preferential translocation of cytoplasmic p53 to mitochondria in CLL cells. Localization of p53 to mitochondria is indicated by the yellow-orange color in the merged image (arrowheads).

Mdm2 inhibitor induces apoptosis independently of Mdm2 or Atm status

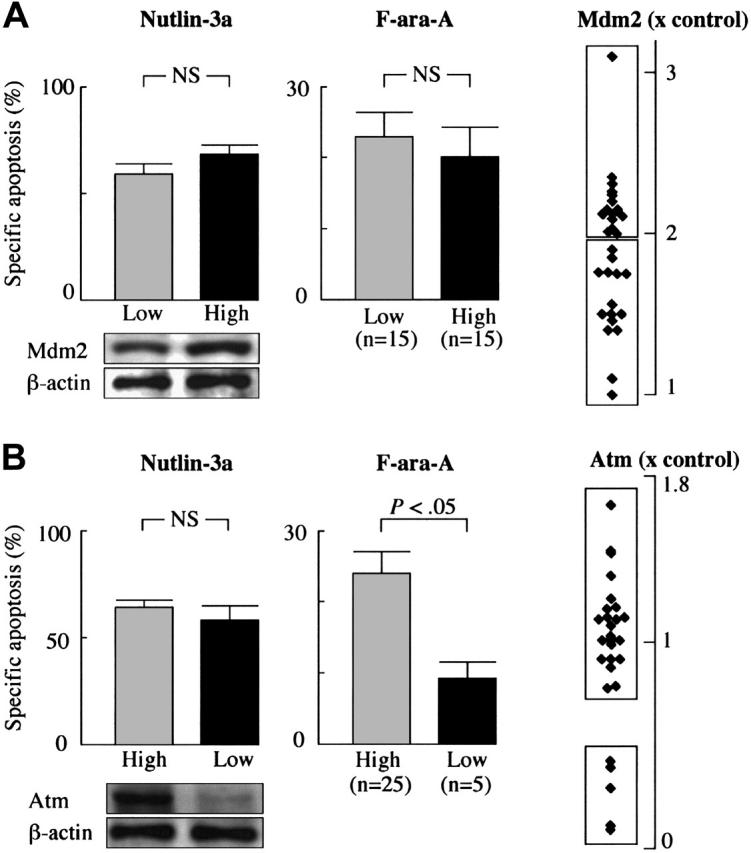

To examine if Mdm2 overexpression or Atm deficiency blocks an apoptogenic effect of Nutlin-3a or F-ara-A, we investigated the protein levels of Mdm2 and Atm in CLL samples. The levels of Mdm2 were more than 2-fold higher in 15 of 30 primary CLL samples than that in normal bone marrow samples (Figure 6A). The frequency of cells with high Mdm2 (> × 2) in CLL (50%) was similar to that in our previous series of 16 primary AML samples (63%).28 On the other hand, the levels of Mdm2 expression in CLL were modest when compared with our previous series of primary AML samples (2.2% ± 0.1% vs 3.9% ± 0.7%, P < .01) in which 5 of 16 samples showed more than 5-fold higher levels of Mdm2 than controls. The percentages of specific annexin V induction at 72 hours by 5 μM Nutlin-3a were similar between samples with low Mdm2 (≤ × 2; 59.5% ± 5.0%) and those with high Mdm2 (>× 2; 68.8% ± 3.8%) (P = .15) (Figure 6A), supporting the previous observation that Mdm2 overexpression is not an obstacle to Nutlin-induced apoptosis.28 This observation was also true of F-ara-A. The percentages of specific annexin V induction at 24 hours by 5 μM F-ara-A in samples with high Mdm2 (20.1% ± 4.4%) were similar to those with low Mdm2 (23.0% ± 3.7%) (P = .61) (Figure 6A). Five samples from patients nos. 9, 10, 25, 27, and 32 (17%) showed a reduction in Atm expression to less than 50% of the level in normal peripheral-blood lymphocytes (Figure 6B). The percentages of specific annexin V induction at 72 hours by 5 μM Nutlin-3a were similar between cases with high Atm (65.2% ± 3.6%) and those with low Atm (58.9% ± 6.7%) (P = .47) (Figure 6B), indicating that the Mdm2 inhibitor can efficiently induce apoptosis in cases with low Atm. In contrast, the percentages of specific annexin V induction by 5 μM F-ara-A were significantly different between cases with high Atm (24.0% ± 3.2%) and those with low Atm (9.1% ± 2.4%) (P < .05 at 24 hours) (Figure 6B), suggesting that F-ara-A may require Atm to fully induce apoptosis in the first 24 hours. The statistically significant difference between cases with high Atm (79.3% ± 2.0%) and those with low Atm (70.9% ± 5.8%) was lost at 72 hours (P = .11). One explanation is that p53-independent activities of F-ara-A do not require Atm function and thus limited the impact of Atm on F-ara-A–induced late apoptosis. Neither high Mdm2 expression nor Atm deficiency was associated with the p53 localization pattern after Nutlin-3a treatment (not shown).

Figure 6.

Nutlin-3a efficiently induces p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL cells independent of Mdm2 or Atm expression levels. (A) High levels of Mdm2 were not associated with resistance to Nutlin-3a– or F-ara-A–induced apoptosis in CLL. Mdm2 protein expression levels relative to an internal control, β-actin, were determined in each sample and compared with normal bone marrow cells. (B) Low Atm levels did not prevent Nutlin-3a from inducing apoptosis in CLL. Atm protein expression levels relative to an internal control, β-actin, were determined in each sample, and compared with normal peripheral-blood lymphocytes. Although low Atm expression was associated with fludarabine resistance in 5 cases, these samples remained sensitive to Nutlin-induced apoptosis. Error bars indicate SEM.

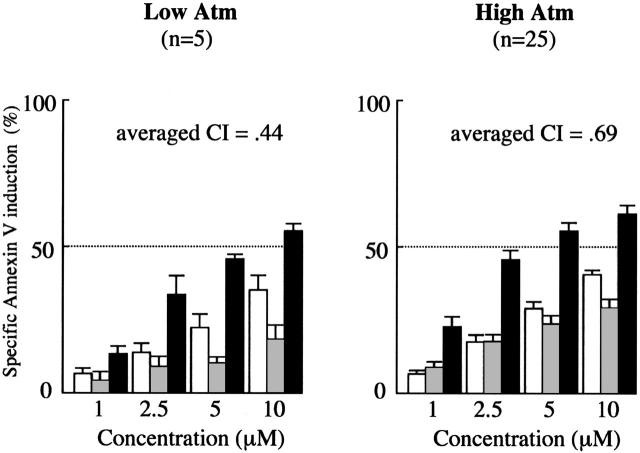

Efficacy of combined treatment with Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A is independent of low Atm cases

To determine if the synergistic apoptotic effect by Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A combination shown in Figure 1 is maintained in low Atm cases, the data at 24 hours from 30 Nutlin-sensitive samples were separately analyzed between low Atm cases (n = 5) and those with high Atm (n = 25). As shown in Figure 7, the averaged CI values were similar between low Atm cases (0.44) and those with high Atm (0.69), suggesting that Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A act synergistically to induce apoptosis in CLL cells independent of ATM status. We also elucidated if the combination effect could be different between cases in which Nutlin-3a induced transcription-independent apoptosis and those with transcription-dependent apoptosis predominance. The averaged CI values at 24 hours in the transcription-independent and transcription-dependent groups were 0.54 and 0.78, respectively. It appeared that the synergism was similarly maintained in both subgroups.

Figure 7.

Synergism between Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A is maintained in low Atm cases. Results of annexin V–binding assay in 30 Nutlin-sensitive samples (Figure 1) were separately analyzed with regard to Atm expression levels. Cells were incubated with the indicated concentrations of Nutlin-3a or F-ara-A, and the annexin V–positive fractions were measured by flow cytometry at 24 hours. Results are expressed as mean ± SEM. □ indicates Nutlin-3a;  , F-ara-A; and ▪, combination.

, F-ara-A; and ▪, combination.

Discussion

Mdm2 inhibition induced apoptosis in most CLL samples (30 [91%] of 33 cases) in a dose- and time-dependent manner, and the resistance to Nutlin-induced apoptosis was associated with TP53 mutations. Of importance, Atm deficiency that is a reported cause of p53 dysfunction in CLL did not inhibit Nutlin-induced apoptosis. Atm is implicated in p53 modifications including phosphorylation at Ser15 and dephosphorylation at Ser376,20,21 which, in certain circumstances, diminish the Mdm2-p53 interaction and enhance transcriptional activity of p53.36,37 Nutlins are nongenotoxic and activate p53 by preventing it from binding to Mdm2.27 They do not bind to p53 or interfere with its phosphorylation status.27,29 The Atm-independent apoptogenic activity of Nutlin-3a would suggest that it sufficiently disrupts Mdm2-p53 interaction in cases with Atm deficiency and that Atm-associated modification of p53 is dispensable for Nutlin-induced apoptosis. The latter notion is in agreement with the recent findings that Nutlins can activate p53 signaling independently of p53 phosphorylation on major serines.29 In contrast, low Atm levels were associated with poor induction of apoptosis by F-ara-A, reflecting different modes of action between Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A in activating the p53 pathway. Regarding Mdm2, we found that high Mdm2 expression is not limiting Nutlin-induced apoptosis in CLL, which is consistent with our previous study in AML.28 In contrast to AML, however, increasing Mdm2 levels were not associated with increased sensitivity to Nutlin-3a. Perhaps a threshold exists for Mdm2 above which levels correlate with cellular susceptibility to Nutlin-induced apoptosis.

We found that fludarabine uses p53-dependent and p53-independent mechanisms to induce apoptosis of CLL cells in a time-specific fashion. Fludarabine induces p53-dependent apoptosis in the early time period (< 24 hours), and later both p53-dependent and p53-independent mechanisms contribute to its apoptogenic activity. This finding is potentially important to in vitro studies that investigate the effect of fludarabine on CLL cells, because p53-mediated induction of apoptosis has been suggested to play a central role in the killing of CLL cells in vivo.11,12 It was of interest that Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A synergistically induced apoptosis in CLL cells. The synergism was evident at 24 hours of treatment when F-ara-A used p53-dependent mechanism to induce apoptosis. The combination treatment of cells with Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A cooperatively induced p53 and Bax conformational change in wild-type p53 but not in mutant p53 cells, further supporting the importance of p53 signaling for the synergistic interaction. We also found that the synergistic interaction between Nutlin-3a and F-ara-A in inducing p53 and apoptosis was maintained in cases with low Atm levels, providing further rationale for this combination strategy in the treatment of CLL that retains wild-type p53.

Aside from its proapoptotic function as a transcription factor, p53 has been recently shown to promote apoptosis independent of transcription.38-41 Better understanding the role of this mechanism versus that of transcriptional regulation will be important in elucidating all aspects of the apoptotic function of p53. We found that activated p53 used both transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways to induce apoptosis in CLL cells. The relative contribution of the 2 pathways to total p53-mediated apoptosis differed widely from case to case. Of interest, activation of the transcription-independent pathway was associated with more profound apoptosis than that of the transcription-dependent pathway. This was not merely attributable to differences in timing of initiation of apoptosis,42 since the difference was still significant at 72 hours. p53 binds to Bcl-2 and Bcl-XL via its DNA binding domain.40,43 Our finding adds to the recent reports emphasizing the important role of transcription-independent over transcription-dependent signaling in p53-mediated apoptosis.44-46 Although the specific mechanisms governing transcription-dependent and transcription-independent pathways remain unknown, our findings suggest that transcription-dependent apoptosis does not always play a major role in p53-mediated apoptosis and that the activation of transcription-independent signaling is sufficient to induce p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL.

We believe that our findings have important clinical implications. Chemotherapeutic agents used in CLL, such as chlorambucil, cyclophosphamide, and fludarabine, mediate cell death through DNA damage and p53-dependent apoptosis.11,47 Although combination treatment of fludarabine with other DNA-damaging chemotherapeutic drugs has improved complete remission rates in CLL patients, the irreversible genotoxic collateral damage may induce genetic instability, selection of drug-resistant tumor subclones, and secondary malignancies. Nutlin-3a synergized with fludarabine to induce p53-mediated apoptosis in CLL cells, while Nutlin-mediated p53 activation is not dependent on DNA damage. The introduction of the nongenotoxic Mdm2 inhibitor may help to avoid or reduce the genotoxic side effects. More importantly, Nutlin-3a activated the p53 pathway and enhanced fludarabine-induced apoptosis in CLL cells independent of Atm status. Although the relationship between Atm protein expression and ATM mutations is not always straightforward, some authors have suggested that patients with CLL who have ATM mutations are refractory to chemotherapy.48,49 The advantage of nongenotoxic Nutlin-3a is further emphasized by the finding that transient induction of p53 response by blockade of the Mdm2-p53 interaction in normal somatic cells leads to reversible growth arrest, not apoptosis.32,50 Treatment of nude mice with Nutlin-3 at therapeutic dose levels was well tolerated without significant weight loss or any gross abnormalities upon necropsy at the end of the treatment.27 These observations suggest that Nutlins could be well tolerated by patients with Nutlin-sensitive malignancies such as AML,28 multiple myeloma,32 and CLL in future clinical trials. Finally, CLL patients with mutant p53 cells, who would not benefit from Nutlins, have been recently reported to benefit from alemtuzumab, a humanized anti-CD52 monoclonal antibody.51

Acknowledgments

Dr Lyubomir T. Vassilev from Hoffmann-La Roche (Nutley, NJ) generously provided Nutlin-3a. The authors acknowledge Ms Rosemarie B. Lauzon and Ms Leslie R. Calvert of the Department of Blood and Marrow Transplantation, The University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center, for their assistance.

Prepublished online as Blood First Edition Paper, March 16, 2006; DOI 10.1182/blood-2005-12-5148.

Supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AML-PO1) CA55164, CA49639, CA89346, and CA16672 and the Paul and Mary Haas Chair in Genetics (M.A.) and by the Kanae Foundation For Life & Socio-Medical Science (2004), the Mochida Memorial Foundation for Medical and Pharmaceutical Research (2004), and Uehara Memorial Foundation (2004) (K.K.).

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. section 1734.

References

- 1.Stevenson FK, Caligaris-Cappio F. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia: revelations from the B-cell receptor. Blood. 2004;103: 4389-4395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson S, Smith AG, Loffler H, et al. Multicentre prospective randomised trial of fludarabine versus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone (CAP) for treatment of advanced-stage chronic lymphocytic leukaemia: The French Cooperative Group on CLL. Lancet. 1996;347: 1432-1438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rai KR, Peterson BL, Appelbaum FR, et al. Fludarabine compared with chlorambucil as primary therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2000;343: 1750-1757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leporrier M, Chevret S, Cazin B, et al. Randomized comparison of fludarabine, CAP, and ChOP in 938 previously untreated stage B and C chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients. Blood. 2001;98: 2319-2325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Byrd JC, Rai K, Peterson BL, et al. Addition of rituximab to fludarabine may prolong progression-free survival and overall survival in patients with previously untreated chronic lymphocytic leukemia: an updated retrospective comparative analysis of CALGB 9712 and CALGB 9011. Blood. 2005;105: 49-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keating MJ, O'Brien S, Albitar M, et al. Early results of a chemoimmunotherapy regimen of fludarabine, cyclophosphamide, and rituximab as initial therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23: 4079-4088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robertson LE, Chubb S, Meyn RE, et al. Induction of apoptotic cell death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia by 2-chloro-2′-deoxyadenosine and 9-beta-D-arabinosyl-2-fluoroadenine. Blood. 1993;81: 143-150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sandoval A, Consoli U, Plunkett W. Fludarabine-mediated inhibition of nucleotide excision repair induces apoptosis in quiescent human lymphocytes. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2: 1731-1741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Genini D, Adachi S, Chao Q, et al. Deoxyadenosine analogs induce programmed cell death in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by damaging the DNA and by directly affecting the mitochondria. Blood. 2000;96: 3537-3543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnston JB, Daeninck P, Verburg L, et al. P53, MDM-2, BAX and BCL-2 and drug resistance in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 1997;26: 435-449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rosenwald A, Chuang EY, Davis RE, et al. Fludarabine treatment of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia induces a p53-dependent gene expression response. Blood. 2004;104: 1428-1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pettitt AR. Mechanism of action of purine analogues in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Br J Haematol. 2003;121: 692-702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas A, El Rouby S, Reed JC, et al. Drug-induced apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: relationship between p53 gene mutation and bcl-2/bax proteins in drug resistance. Oncogene. 1996;12: 1055-1062. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pettitt AR, Clarke AR, Cawley JC, Griffiths SD. Purine analogues kill resting lymphocytes by p53-dependent and -independent mechanisms. Br J Haematol. 1999;105: 986-988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dohner H, Fischer K, Bentz M, et al. p53 gene deletion predicts for poor survival and non-response to therapy with purine analogs in chronic B-cell leukemias. Blood. 1995;85: 1580-1589. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.El Rouby S, Thomas A, Costin D, et al. p53 gene mutation in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia is associated with drug resistance and is independent of MDR1/MDR3 gene expression. Blood. 1993;82: 3452-3459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lens D, Dyer MJ, Garcia-Marco JM, et al. p53 abnormalities in CLL are associated with excess of prolymphocytes and poor prognosis. Br J Haematol. 1997;99: 848-857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cordone I, Masi S, Mauro FR, et al. p53 expression in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: a marker of disease progression and poor prognosis. Blood. 1998;91: 4342-4349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pettitt AR, Sherrington PD, Stewart G, Cawley JC, Taylor AM, Stankovic T. p53 dysfunction in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia: inactivation of ATM as an alternative to TP53 mutation. Blood. 2001;98: 814-822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khanna KK, Keating KE, Kozlov S, et al. ATM associates with and phosphorylates p53: mapping the region of interaction. Nat Genet. 1998;20: 398-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Waterman MJ, Stavridi ES, Waterman JL, Halazonetis TD. ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins. Nat Genet. 1998;19: 175-178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stankovic T, Weber P, Stewart G, et al. Inactivation of ataxia telangiectasia mutated gene in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Lancet. 1999;353: 26-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Starostik P, Manshouri T, O'Brien S, et al. Deficiency of the ATM protein expression defines an aggressive subgroup of B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 1998;58: 4552-4557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Haidar MA, El-Hajj H, Bueso-Ramos CE, et al. Expression profile of MDM-2 proteins in chronic lymphocytic leukemia and their clinical relevance. Am J Hematol. 1997;54: 189-195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konikova E, Kusenda J. Altered expression of p53 and MDM2 proteins in hematological malignancies. Neoplasma. 2003;50: 31-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moll UM, Petrenko O. The MDM2-p53 interaction. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1: 1001-1008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303: 844-848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kojima K, Konopleva M, Samudio IJ, et al. MDM2 antagonists induce p53-dependent apoptosis in AML: implications for leukemia therapy. Blood. 2005;106: 3150-3159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thompson T, Tovar C, Yang H, et al. Phosphorylation of p53 on key serines is dispensable for transcriptional activation and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2004;279: 53015-53022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schuler M, Green DR. Transcription, apoptosis and p53: catch-22. Trends Genet. 2005;21: 182-187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bellosillo B, Villamor N, Lopez-Guillermo A, et al. Spontaneous and drug-induced apoptosis is mediated by conformational changes of Bax and Bak in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100: 1810-1816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stuhmer T, Chatterjee M, Hildebrandt M, et al. Nongenotoxic activation of the p53 pathway as a therapeutic strategy for multiple myeloma. Blood. 2005;106: 3609-3617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackus WJ, Kater AP, Grummels A, et al. Chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells display p53-dependent drug-induced Puma upregulation. Leukemia. 2005;19: 427-434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Decker T, Oelsner M, Kreitman RJ, et al. Induction of caspase-dependent programmed cell death in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia by anti-CD22 immunotoxins. Blood. 2004;103: 2718-2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Desagher S, Osen-Sand A, Nichols A, et al. Bid-induced conformational change of Bax is responsible for mitochondrial cytochrome c release during apoptosis. J Cell Biol. 1999;144: 891-901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lambert PF, Kashanchi F, Radonovich MF, Shiekhattar R, Brady JN. Phosphorylation of p53 serine 15 increases interaction with CBP. J Biol Chem. 1998;273: 33048-33053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bode AM, Dong Z. Post-translational modification of p53 in tumorigenesis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2004;4: 793-805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chipuk JE, Kuwana T, Bouchier-Hayes L, et al. Direct activation of Bax by p53 mediates mitochondrial membrane permeabilization and apoptosis. Science. 2004;303: 1010-1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leu JI, Dumont P, Hafey M, Murphy ME, George DL. Mitochondrial p53 activates Bak and causes disruption of a Bak-Mcl1 complex. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6: 443-450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mihara M, Erster S, Zaika A, et al. p53 has a direct apoptogenic role at the mitochondria. Mol Cell. 2003;11: 577-590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Moll UM, Wolff S, Speidel D, Deppert W. Transcription-independent pro-apoptotic functions of p53. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17: 631-636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Erster S, Mihara M, Kim RH, Petrenko O, Moll UM. In vivo mitochondrial p53 translocation triggers a rapid first wave of cell death in response to DNA damage that can precede p53 target gene activation. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24: 6728-6741. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Petros AM, Gunasekera A, Xu N, Olejniczak ET, Fesik SW. Defining the p53 DNA-binding domain/Bcl-XL-binding interface using NMR. FEBS Lett. 2004;559: 171-174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kakudo Y, Shibata H, Otsuka K, Kato S, Ishioka C. Lack of correlation between p53-dependent transcriptional activity and the ability to induce apoptosis among 179 mutant p53s. Cancer Res. 2005;65: 2108-2114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arima Y, Nitta M, Kuninaka S, et al. Transcriptional blockade induces p53-dependent apoptosis associated with translocation of p53 to mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2005;280: 19166-19176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Speidel D, Helmbold H, Deppert W. Dissection of transcriptional and non-transcriptional p53 activities in the response to genotoxic stress. Oncogene. 2006;25: 940-953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Thomas A, Pepper C, Hoy T, Bentley P. Bcl-2 and bax expression and chlorambucil-induced apoptosis in the T-cells and leukaemic B-cells of untreated B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukaemia patients. Leuk Res. 2000;24: 813-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Austen B, Powell JE, Alvi A, et al. Mutations in the ATM gene lead to impaired overall and treatment-free survival that is independent of IGVH mutation status in patients with B-CLL. Blood. 2005;106: 3175-3182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lin K, Sherrington PD, Dennis M, Matrai Z, Cawley JC, Pettitt AR. Relationship between p53 dysfunction, CD38 expression, and IgVH mutation in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood. 2002;100: 1404-1409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Carvajal D, Tovar C, Yang H, Vu BT, Heimbrook DC, Vassilev LT. Activation of p53 by MDM2 antagonists can protect proliferating cells from mitotic inhibitors. Cancer Res. 2005;65: 1918-1924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lozanski G, Heerema NA, Flinn IW, et al. Alemtuzumab is an effective therapy for chronic lymphocytic leukemia with p53 mutations and deletions. Blood. 2004;103: 3278-3281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]