Abstract

CD30 is a member of the TNF receptor superfamily. Overexpression of CD30 on some neoplasms versus limited expression on normal tissues makes this receptor a promising target for antibody-based therapy. Radioimmunotherapy of cancer with radiolabeled antibodies has shown promise. In this study, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of an anti-CD30 antibody, HeFi-1, armed with 211At in a leukemia (karpas299) model and with 90Y in a lymphoma (SUDHL-1) model. Furthermore, we investigated the combination therapy of 211At-HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 in the leukemia model. Treatment with unmodified HeFi-1 significantly prolonged the survival of the karpas299-bearing mice compared with the controls (P < 0.001). Treatment with 211At-HeFi-1 showed greater therapeutic efficacy than that with unmodified HeFi-1 as shown by survival of the mice (P < 0.001). Combining these two agents further improved the survival of the mice compared with the groups treated with either 211At-HeFi-1 (P < 0.05) or unmodified HeFi-1 (P < 0.001) alone. In the lymphoma model, the survival of the SUDHL-1-bearing mice was significantly prolonged by the treatment with 90Y-HeFi-1 compared with the controls (P < 0.001). In summary, radiolabeled HeFi-1 is very promising for the treatment of CD30-expressing leukemias and lymphomas, and the combination regimen of 211At-HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 enhanced the therapeutic efficacy.

Keywords: monoclonal antibody, radioimmunotherapy, α-emitter, β-emitter

CD30 is a member of the TNF receptor superfamily, which includes TNF-R1, TNF-R2, Fas-R, CD40, CD27, and TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand receptor (1). Increased expression of CD30 is observed on some neoplasms including Hodgkin's disease (HD), anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), mediastinal B cell lymphoma, embryonal carcinoma, seminoma, and mesothelioma (2–7). In contrast, CD30 expression in normal tissues is limited to activated T cells, activated B cells, select thymocytes, and some vascular beds (2). This expression of CD30 on neoplasms versus its limited expression on normal tissues makes it a promising target for antibody-based therapy.

Both HD and ALCL are characterized by the strong expression of CD30 on the malignant cell surfaces. Although HD in most patients can be cured by standard approaches even in advanced stages, <30% of those who have a relapse attain durable remissions after second-line treatment (8). The outcome is even worse for those with primary refractory disease (9). ALCL represents a heterogeneous group of aggressive non-HD (10). Despite responsiveness to chemotherapy, approximately one-third of the patients with ALCL die regardless of intensive chemotherapy (10). Therefore, more effective approaches need to be developed. In addition, data from HD and non-HD suggest that small numbers of residual tumor cells remaining after first-line treatment can give rise to a late relapse (11). Thus, eliminating residual malignant lymphoma cells after first-line treatment might further improve the outcome in these diseases.

Anti-CD30 monoclonal antibodies have been investigated for the treatment of CD30-expressing malignancies in vitro and in vivo (10, 12–18). CD30-mediated signal transduction is capable of promoting cell proliferation and cell survival as well as antiproliferative effects and cell death depending on cell type and costimulatory effects (19). Several studies have shown that anti-CD30 monoclonal antibodies possessing signaling properties could inhibit the growth of ALCL cells, but very few of them were effective for HD cells (10, 12, 13, 18). Furthermore, although preclinical studies showed that treatment with anti-CD30 monoclonal antibodies prolonged the survival of ALCL-bearing mice significantly, compared with the mice in the control group, many of the mice in the treatment group still died of the disease (15, 16). Therefore, alternative strategies need to be developed for CD30-targeted therapy.

Monoclonal antibodies directed against tumor-associated antigens armed with diverse radionuclides are being investigated as therapeutic agents for the treatment of malignant disease (20–24). Although encouraging results have been obtained in the treatment of lymphoma with monoclonal antibodies armed with β-emitting radionuclides, further development is needed to achieve an ideal radioimmunotherapeutic agent (23, 24). The α-emitting radionuclides are very attractive for cancer therapy, especially for isolated malignant cells as are observed in leukemia, because of their high linear energy transfer and short effective path length in tissues (25–27). Among the α-emitters currently under investigation for use in radioimmunotherapy, 211At is perhaps the most promising candidate for radioimmunotherapeutic applications on the basis of half-life (t1/2 = 7.2 h) considerations. In contrast, β-emitters such as 90Y that act through crossfire may be preferable in the treatment of large tumor masses (28–30). In the clinical situation, this latter agent may eliminate nontargeted tumor cells through the crossfire effect emanating from neighboring antigen-bearing cells that have been targeted by the radiolabeled monoclonal antibody.

A paradigm is also emerging that, for cancer therapy, the addition of two therapeutic agents that function via different mechanisms may be greater than additive in their cytotoxic action, leading to malignant cell death (30–36). In our previous therapeutic trials, we demonstrated that the therapeutic efficacy of radioimmunotherapy for an adult T cell leukemia model was enhanced by the simultaneous coadministration of an anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody, daclizumab, at receptor-saturating doses (30, 32, 36).

In this study, we investigated the therapeutic efficacy of the 211At-HeFi-1 in a leukemia model and 90Y-HeFi-1 in a lymphoma model. Furthermore, we investigated the combination regimen of 211At-HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 in the leukemia model. Our findings suggest that radiolabeled HeFi-1 is very promising for the treatment of patients with CD30-expressing leukemias and lymphomas and the combination of radiolabeled HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 significantly improved the therapeutic efficacy.

Results

Immunoreactivity of Radiolabeled HeFi-1.

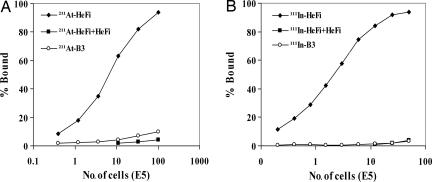

For a radiolabeled antibody to be effective, the labeling procedure should not compromise antibody specificity. We tested the bindability of 211At-HeFi-1 and 111In-HeFi-1 with karpas299 and SUDHL-1 cells, respectively, in vitro. The 211At-HeFi-1 and 111In-HeFi-1 specifically bound to the cells with maximum bindings of >90% of the added radiolabeled antibodies (Fig. 1). The bindings were specifically inhibited by unmodified HeFi-1 (Fig. 1). Radiolabeled B3, which was used as a nonspecific, isotype-matched control antibody, did not bind to the cells (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Immunoreactivity of radiolabeled HeFi-1. (A) 211At-HeFi-1 with karpas299 cells. (B) 111In-HeFi-1 with SUDHL-1 cells. The cell-binding assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Both 211At-HeFi-1 and 111In-HeFi-1 bound to the CD30-positive cells specifically with the maximum bindings of >90% of added radioactivity. The binding was inhibited by the addition of a 1,000-fold greater concentration of unmodified HeFi-1. Radiolabeled B3 did not bind to the cells.

Antiproliferative Effect.

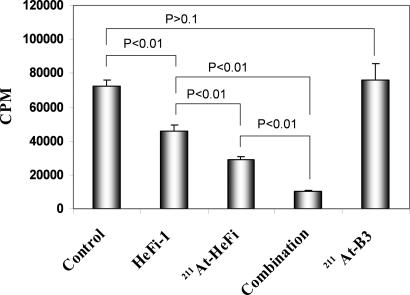

Karpas299 cells were treated with 211At-HeFi-1 or unmodified HeFi-1 alone or with the combination of 211At-HeFi-1 and unmodified HeFi-1. Unmodified HeFi-1 and 211At-HeFi-1 inhibited the proliferation of the cells by 40% and 60%, respectively, after 2 days of incubation compared with cells treated with medium alone or with the radiolabeled, isotype-matched control, 211At-B3 (Fig. 2). In addition, the combination of 211At-HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 enhanced the antitumor efficacy with >80% of the proliferation of the cells being inhibited (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The effect of 211At-HeFi-1 or unmodified HeFi-1 or their combination on the proliferation of karpas299 cells in vitro. Karpas299 cells were treated as described in Materials and Methods. The data represent means ± SD of six samples and are representative of three experiments. Unmodified HeFi-1 and 211At-HeFi-1 inhibited the proliferation of karpas299 cells by 40% and 60%, respectively, compared with cells treated with medium alone. The combination of 211At-HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 enhanced the antitumor efficacy with >80% of proliferation of the cells being inhibited.

Therapy Study.

In karpas299 leukemia model.

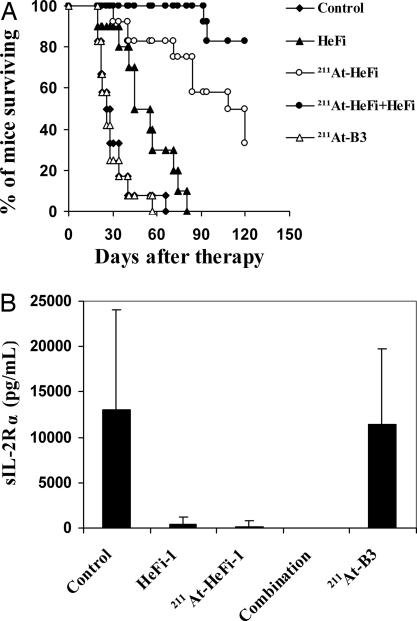

The therapeutic study with 211At-HeFi-1 was performed in the karpas299 model. Treatment with unmodified HeFi-1 administered at a dose of 100 μg weekly for 4 weeks showed effective therapeutic results with partial remissions and a prolongation of survival of the karpas299-bearing mice compared with the control group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A), a result similar to that we reported previously (16). The i.v. administration of a single dose of 12 μCi (0.444 MBq) of 211At-HeFi-1 showed greater efficacy than unmodified HeFi-1, as seen by the prolonged survival of the mice (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). Treatment with 211At-HeFi-1 inhibited the leukemia growth significantly as seen by the reduced serum levels of soluble interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2Rα) in the 211At-HeFi-1 treatment group compared with the control or radiolabeled nonspecific antibody, 211At-B3, group (Fig. 3B). At day 26 after therapy, the average concentrations of serum sIL-2Rα were 12,992 and 11,443 pg/ml in the control and 211At-B3 groups, respectively, whereas the average concentrations of serum sIL-2Rα were reduced to 397 and 172 pg/ml with the treatment of unmodified HeFi-1 and 211At-HeFi-1, respectively (Fig. 3B). In addition, the serum sIL-2Rα was undetectable in the combination group at day 26 after therapy (Fig. 3B). Furthermore, the treatment with 211At-HeFi-1 or unmodified HeFi-1 or their combination significantly prolonged survival of the karpas299-bearing mice compared with the control and 211At-B3 groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A). The combination of a single dose of 12 μCi (0.444 MBq) of 211At-HeFi-1 with four doses of 100 μg of unmodified HeFi-1 provided further improvement in survival of the mice, compared with the groups treated either with 211At-HeFi-1 (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3A) or with unmodified HeFi-1 (P < 0.001) (Fig. 3A) alone. The median survival duration of the control group was 26 days, whereas it was prolonged to 50 and 114 days in the unmodified HeFi-1 and 211At-HeFi-1 groups, respectively. All of the mice in the control and 211At-B3 groups died by day 66. In contrast, 33% of the mice in the 211At-HeFi-1 group and 83% in the combination group survived >4 months and had undetectable serum sIL-2Rα levels.

Fig. 3.

Therapeutic study of 211At-HeFi-1 or unmodified HeFi-1 or their combination in the karpas299 leukemia model. (A) Kaplan–Meier survival plot of the karpas299 leukemia-bearing SCID/NOD mice. (B) Serum sIL-2Rα levels of the karpas299 leukemia-bearing SCID/NOD mice at day 26 after therapy. The treatment with unmodified HeFi-1 or 211At-HeFi-1 inhibited the tumor growth significantly as seen by the reduced concentrations of serum sIL-2Rα at day 26, compared with those in the control and 211At-B3 groups. The combination of these two therapeutic agents further improved the efficacy as shown by the undetectable sIL-2Rα levels in this group at day 26. Survival of the karpas299-bearing mice was significantly prolonged in the unmodified HeFi-1 group compared with those in the control and 211At-B3 groups (P < 0.001). Treatment with a single dose of 12 μCi of 211At-HeFi-1 showed more effective therapeutic results in the karpas299 model compared with unmodified HeFi-1 (P < 0.001). The combination of these two therapeutic agents provided further improvement in survival of the mice, compared with the groups treated either with 211At-HeFi-1 (P < 0.05) or with unmodified HeFi-1 (P < 0.001) alone.

In SUDHL-1 lymphoma model.

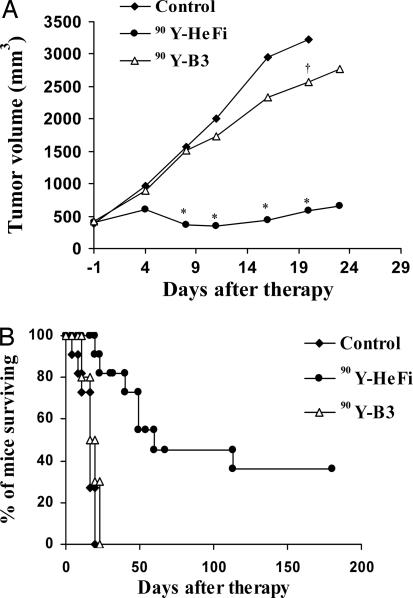

Radioimmunotherapy with i.v.-administered 90Y-HeFi-1 was performed in the SUDHL-1 lymphoma-bearing nude mice. SUDHL-1 tumors in the control group grew rapidly, from 0.4 cm3 at the initiation of the experiment, to ≥2 cm3 within 3 weeks (Fig. 4A), and these mice were killed according to our animal protocol. Treatment with 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 90Y-HeFi-1 inhibited the tumor growth significantly compared with the control group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4A). Four of the 11 mice in the 90Y-HeFi-1 treatment group became tumor-free and remained healthy for >6 months. The median survival duration of this group was 60 days, significantly longer than the 16 days of the control group (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B). To confirm the specificity of the therapeutic effect of 90Y-HeFi-1, we used the irrelevant mouse IgG1 monoclonal antibody, B3, armed with 90Y in the same model. Although the treatment with 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 90Y-B3 slightly slowed down the tumor growth compared with the control group (P < 0.05) (Fig. 4A), the median survival duration in this group was 20 days, similar to the 16 days in the control group (P > 0.05) (Fig. 4B). There was a significant difference in the survival of the mice between the 90Y-HeFi-1 and 90Y-B3 groups (P < 0.001) (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Therapeutic study of 90Y-HeFi-1 in the SUDHL-1 model. (A) Tumor volume. (B) Kaplan–Meier survival plot of the SUDHL-1-bearing nude mice. Treatment with 90Y-HeFi-1 inhibited the SUDHL-1 lymphoma growth significantly as seen by tumor size and prolonged survival of the SUDHL-1-bearing mice compared with the control and 90Y-B3 groups. ∗, P < 0.001; †, P < 0.05, compared with the control group.

Discussion

The development of the hybridoma technique rekindled interest in the use of antibodies targeted to cell surface antigens to treat cancer patients. However, such monoclonal antibodies have been largely ineffective with only a few exceptions in this arena. Arming of monoclonal antibodies with toxins or radionuclides to specifically target these cytotoxic agents to tumor cells provides a valuable augmentation of their therapeutic efficacy (28, 37, 38).

One pivotal issue to be addressed in all systemic radioimmunotherapy trials is the selection of a monoclonal antibody that targets the tumor and thereby defines the type of malignancy chosen as the target for radioimmunotherapy. In the present study, we have chosen CD30 as our target for radioimmunotherapy. The scientific basis for this choice is that CD30 is overexpressed by some neoplasms including HD and ALCL and expressed in a very limited way by normal tissues (2–7), making this receptor a promising target for antibody-based therapy. Indeed, monoclonal antibodies to CD30 have been evaluated for the treatment of CD30-expressing malignancies (10, 12–18). However, the therapeutic results were very different with different types of malignancies. Therefore, therapy with radioimmunoconjugates provides an alternative strategy for CD30-targeted treatment of malignancies (1).

Another pivotal issue in defining an optimal radioimmunotherapeutic agent is to consider the nature of the radionuclide used in relationship to the nature of the diseases being treated. A β-emitting radionuclide such as 90Y that acts through crossfire is preferable in the treatment of large tumor masses such as those that occur with the SUDHL-1 model. In the clinical situation, this agent may eliminate nontargeted tumor cells through the crossfire effect emanating from neighboring antigen-bearing cells that have been targeted by the radiolabeled monoclonal antibody (28). Nevertheless, the use of β-emitting radionuclides is limited as the target mass decreases the benefit of the crossfire effect also decreases, whereas the potential for normal tissue damage increases (32). With small tumors, including micrometasteses, individual tumor cells, and leukemic cells, the therapeutic efficacy of β-emitters may be limited because high-energy β-emitting radionuclides such as 90Y deliver a high dose of irradiation to normal tissues owing to the long range of β irradiation. For such cellular populations, the development of radiolabeled monoclonal antibody-mediated approaches may focus on α-emitting radionuclides, which may be the most effective agents for killing isolated leukemic cells without damaging normal tissues. Radionuclides emitting α-particles have a high linear energy transfer (6- to 9-MeV particles) that act over 10–80 μm and are effective at killing individual target cells (39). We have demonstrated that 211At-labeled 7G7/B6, an anti-CD25 monoclonal antibody, was very effective in the treatment of murine models of leukemia (36, 40). A phase I clinical trial with 213Bi-HuM195 in the treatment of patients with relapsed and refractory acute or chronic myelogenous leukemia was reported to show promising results (41). In the present study, we demonstrated that 211At linked to the anti-CD30 monoclonal antibody, HeFi-1, provided effective therapy for the karpas299 leukemia model. A paradigm is emerging in monoclonal antibody-mediated treatment that therapeutic efficacy may be augmented through the use of two agents with different modes of action (30–36). In this study, we used 211At-HeFi-1, which causes radiation damage to the tumor cells, followed by the administration of receptor-saturating doses of unmodified HeFi-1. Previously, we demonstrated that in the karpas299 model, unmodified HeFi-1 is directly cytotoxic to the malignant cells by a process that does not require activating FcRγI, III, or IV expression by the recipient mice (16). The combination regimen of 211At-HeFi-1 with unmodified HeFi-1 significantly improved the therapeutic efficacy in the treatment of the karpas299-bearing mice compared with that of either agent used alone. Therefore, the findings from this study support the use of the radiolabeled HeFi-1 as well as its combination with unmodified HeFi-1 in a clinical trial involving the treatment of patients with CD30-expressing leukemias and lymphomas.

Materials and Methods

Tumor Cell Lines and Mouse Models.

Karpas299 and SUDHL-1 are human ALCL cell lines that express CD30 on their cell surfaces. The cells were grown in RPMI medium 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated FCS, 100 units/ml penicillin, and 100 μg/ml streptomycin in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2. Severe combined immunodeficient/nonobese diabetic (SCID/NOD) mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and nude mice came from the National Cancer Institute–Frederick (Frederick, MD).The karpas299 model, which was established by i.v. injection of 1 × 107 karpas299 cells into SCID/NOD mice, served as a leukemia model. The SUDHL-1 model, which was established by s.c. injection of 1 × 107 SUDHL-1 cells in the right flank of nude mice, served as a solid tumor model. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with National Cancer Institute Animal Care and Use Committee guidelines. The National Cancer Institute–Frederick is accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care international and follows the U.S. Public Health Service policy for the care and use of laboratory animals. Animal care was provided in accordance with the procedures outlined in the Guide for Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (42).

Monoclonal Antibodies.

HeFi-1, which is a mouse IgG1 directed toward the ligand-binding site on CD30, was provided by the Biological Response Modifiers Program, National Cancer Institute–Frederick Cancer Research Center (Frederick, MD). B3, a mouse IgG1 antibody reacting with a carbohydrate epitope found on the Ley and the polyfucosylated-Lex antigens (43), was used as an isotype-matched control antibody that did not bind to karpas299 and SUDHL-1 cells.

Radiolabeling of Monoclonal Antibodies.

Production and purification of 211At as well as the procedure for the labeling of the antibodies with 211At were recently reported in detail (44, 45). In brief, 211At was produced by using the 209Bi (α2n) 211At reaction by irradiating a bismuth target with an α beam from a CS-30 cyclotron (Cyclotron Corporation, Berkeley, CA). The 211At was isolated as described previously (44). HeFi-1 or B3 was labeled with 211At by using the linker, N-succinimidyl N-(4-astatophenethyl)succinamate, as described previously (45). The specific activities of 211At-labeled antibodies were 5–10 μCi/μg (0.185–0.37 MBq/μg). HeFi-1 and B3 were conjugated with 2-(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl)cyclohexyl-diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid (CHX-A″). The conjugation of the antibodies with CHX-A″ was performed as previously described (46). HeFi-1-CHX-A″ and B3-CHX-A″ were labeled with 90Y (NEN, Boston, MA) at specific activities of 10–30 μCi/μg (0.37–1.11 MBq/μg) for therapeutic studies as described previously (47). HeFi-1-CHX-A″ and B3-CHX-A″ were labeled with 111In (Amersham, Piscataway, NJ) at specific activities of 5 μCi/μg (0.185 MBq/μg) for immunoreactivity assay.

Immunoreactivity Assay.

The immunoreactivity of radiolabeled HeFi-1 was evaluated by using the karpas299 and SUDHL-1 cells. Briefly, 211At-HeFi-1 or 111In-HeFi-1 (5 ng) was incubated with an increasing number of the cells (2 × 104 to 1 × 107) with or without unlabeled HeFi-1 (25 μg per tube) inhibition at 4°C for 1 h. After centrifugation, the supernatant was aspirated, and the radioactivity bound to the cells was quantitated in a γ counter (Wallac, Turku, Finland).

Proliferation Assay.

Karpas299 cells were resuspended at a concentration of 2 × 106 cells per ml and incubated with 211At-HeFi-1 or 211At-B3 (1 μCi/0.5 μg/ml) or medium alone at 37°C for 20 min. After centrifugation, the supernatant was aspirated, and the cells were washed once with medium. Then the karpas299 cells were resuspended in medium again, and aliquots of 1 × 104 cells per 100 μl were seeded in 96-well culture plates. After incubation at 37°C overnight, 100 μl of medium containing unmodified HeFi-1 or medium alone was added to appropriate wells, and the final concentration of the antibody was 10 μg/ml. The cells were pulsed after 1 or 2 days of culture for 6 h with 1 μCi (0.037 MBq) of [3H]thymidine. Then the cells were harvested with a 96-well harvester (Tomtec, Hamden, CT) and counted in a β counter (Wallac). The assay was performed in six samples simultaneously on three occasions.

Therapy Study.

In karpas299 model.

The therapeutic study with 211At-HeFi-1 was performed on karpas299-bearing SCID/NOD mice at day 7 after the cell inoculation. There were five groups in the therapeutic study. Group 1, the PBS control, received 200 μl of PBS weekly for 4 weeks. Group 2, the unmodified HeFi-1 group, was given i.v. injections of 100 μg of HeFi-1 on days 0, 7, 14, and 21. Group 3, the 211At-HeFi-1 group, received a single dose of 12 μCi (0.444 MBq) of 211At-HeFi-1. Group 4, the combination group, received a combined therapy of 12 μCi (0.444 MBq) of 211At-HeFi-1 on day 0 with unmodified HeFi-1 given on days 1, 7, 14, and 21 at a dose of 100 μg. Group 5, the 211At-B3 group, received a single dose of 12 μCi (0.444 MBq) of 211At-B3 and served as a radiolabeled, nonspecific, isotype-matched control.

In SUDHL-1 model.

The therapeutic study with 90Y-HeFi-1 was performed on SUDHL-1-bearing nude mice when xenografted tumors typically reached ≈0.5 cm in maximal diameter. There were three groups in the therapeutic study. Group 1, the PBS control, received 200 μl of PBS. Group 2, the 90Y-HeFi-1 group, received a single dose of 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 90Y-HeFi-1. Group 3, the 90Y-B3 group, received a single dose of 100 μCi (3.7 MBq) of 90Y-B3 and served as a radiolabeled, nonspecific, isotype-matched control.

Monitoring of Tumor Growth.

The growth of karpas299 leukemia was monitored by serum levels of human sIL-2Rα, a surrogate tumor marker that was indicative of the tumor load in the murine model (16). Measurement of the serum concentrations of the sIL-2Rα was performed by using an ELISA. The ELISA kit was purchased from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN), and the ELISAs were performed as indicated in the manufacturer's kit inserts. SUDHL-1 tumor growth was monitored by measuring tumor size twice a week for 2 weeks after treatment and then once per week. A digital caliper was used to measure the tumor in two orthogonal dimensions. The volume was calculated by using the formula (long dimension)(short dimension)2/2. Body weight and survival of both karpas299- and SUDHL-1-bearing mice were monitored throughout the experiments.

Statistical Analysis.

The data from in vitro proliferation assay and tumor volumes at different time points for the different treatment groups were analyzed for statistical significance by using the GraphPad Prism program (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). One-way ANOVA was used among groups, followed by the Mann–Whitney U test for post hoc comparisons to determine P values. The statistical significance of differences in survival of the mice in different groups was determined by the log-rank test using the same program.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Ira Pastan (National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health) for providing the B3 antibody. This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research; and the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health under Contract N01-CO-12400.

Abbreviations

- HD

Hodgkin's disease

- ALCL

anaplastic large cell lymphoma

- sIL-2R

soluble interleukin-2 receptor

- SCID/NOD

severe combined immunodeficient/nonobese diabetic

- CHX-A″

(p-isothiocyanatobenzyl)cyclohexyldiethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Koon HB, Junghans RP. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12:588–593. doi: 10.1097/00001622-200011000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.de Bruin PC, Gruss HJ, van der Valk P, Willemze R, Meijer CJ. Leukemia. 1995;9:1620–1627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Durkop H, Foss HD, Eitelbach F, Anagnostopoulos I, Latza U, Pileri S, Stein H. J Pathol. 2000;190:613–618. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(200004)190:5<613::AID-PATH559>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Higgins JP, Warnke RA. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999;112:241–247. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/112.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kadin ME. Semin Dermatol. 1991;10:164–171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Latza U, Foss HD, Durkop H, Eitelbach F, Dieckmann KP, Loy V, Unger M, Pizzolo G, Stein H. Am J Pathol. 1995;146:463–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rudolph P, Lappe T, Schmidt D. Histopathology. 1993;23:173–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2559.1993.tb00476.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carella AM. Leuk Lymphoma. 1992;7(Suppl):21–22. doi: 10.3109/10428199209061559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Josting A, Reiser M, Rueffer U, Salzberger B, Diehl V, Engert A. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:332–339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2000.18.2.332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schneider C, Stohr D, Merz H, Hubinger G. Leuk Lymphoma. 2004;45:1009–1015. doi: 10.1080/1042819031000149322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kanzler H, Hansmann ML, Kapp U, Wolf J, Diehl V, Rajewsky K, Kuppers R. Blood. 1996;87:3429–3436. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hubinger G, Muller E, Scheffrahn I, Schneider C, Hildt E, Singer BB, Sigg I, Graf J, Bergmann L. Oncogene. 2001;20:590–598. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mir SS, Richter BW, Duckett CS. Blood. 2000;96:4307–4312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pfeifer W, Levi E, Petrogiannis-Haliotis T, Lehmann L, Wang Z, Kadin ME. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1353–1359. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65237-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tian ZG, Longo DL, Funakoshi S, Asai O, Ferris DK, Widmer M, Murphy WJ. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5335–5341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhang M, Yao Z, Zhang Z, Garmestani K, Goldman CK, Ravetch JV, Janik J, Brechbiel MW, Waldmann TA. Blood. 2006;108:705–710. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borchmann P, Treml JF, Hansen H, Gottstein C, Schnell R, Staak O, Zhang HF, Davis T, Keler T, Diehl V, et al. Blood. 2003;102:3737–3742. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-02-0515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wahl AF, Klussman K, Thompson JD, Chen JH, Francisco LV, Risdon G, Chace DF, Siegall CB, Francisco JA. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3736–3742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schneider C, Hubinger G. Leuk Lymphoma. 2002;43:1355–1366. doi: 10.1080/10428190290033288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaminski MS, Estes J, Zasadny KR, Francis IR, Ross CW, Tuck M, Regan D, Fisher S, Gutierrez J, Kroll S, et al. Blood. 2000;96:1259–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaminski MS, Tuck M, Estes J, Kolstad A, Ross CW, Zasadny K, Regan D, Kison P, Fisher S, Kroll S, et al. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:441–449. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa041511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Knox SJ, Goris ML, Trisler K, Negrin R, Davis T, Liles TM, Grillo-Lopez A, Chinn P, Varns C, Ning SC, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 1996;2:457–470. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Press OW, Eary JF, Appelbaum FR, Martin PJ, Nelp WB, Glenn S, Fisher DR, Porter B, Matthews DC, Gooley T, et al. Lancet. 1995;346:336–340. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(95)92225-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waldmann TA, White JD, Carrasquillo JA, Reynolds JC, Paik CH, Gansow OA, Brechbiel MW, Jaffe ES, Fleisher TA, Goldman CK. Blood. 1995;86:4063–4075. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Macklis RM, Kinsey BM, Kassis AI, Ferrara JL, Atcher RW, Hines JJ, Coleman CN, Adelstein SJ, Burakoff SJ. Science. 1988;240:1024–1026. doi: 10.1126/science.2897133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McDevitt MR, Ma D, Lai LT, Simon J, Borchardt P, Frank RK, Wu K, Pellegrini V, Curcio MJ, Miederer M, et al. Science. 2001;294:1537–1540. doi: 10.1126/science.1064126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mulford DA, Scheinberg DA, Jurcic JG. J Nucl Med. 2005;46(Suppl 1):199S–204S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Milenic DE, Brady ED, Brechbiel MW. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2004;3:488–499. doi: 10.1038/nrd1413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yao Z, Zhang M, Axworthy DB, Wong KJ, Garmestani K, Park L, Park CW, Mallett RW, Theodore LJ, Yau EK, et al. Cancer Res. 2002;62:5755–5760. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang M, Zhang Z, Garmestani K, Schultz J, Axworthy DB, Goldman CK, Brechbiel MW, Carrasquillo JA, Waldmann TA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:1891–1895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437788100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tan C, Waldmann TA. Cancer Res. 2002;62:1083–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang M, Yao Z, Garmestani K, Axworthy DB, Zhang Z, Mallett RW, Theodore LJ, Goldman CK, Brechbiel MW, Carrasquillo JA, et al. Blood. 2002;100:208–216. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-01-0107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang M, Zhang Z, Goldman CK, Janik J, Waldmann TA. Blood. 2005;105:1231–1236. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-05-1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coiffier B, Lepage E, Briere J, Herbrecht R, Tilly H, Bouabdallah R, Morel P, Van Den Neste E, Salles G, Gaulard P, et al. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:235–242. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Slamon DJ, Leyland-Jones B, Shak S, Fuchs H, Paton V, Bajamonde A, Fleming T, Eiermann W, Wolter J, Pegram M, et al. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:783–792. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103153441101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang Z, Zhang M, Garmestani K, Talanov VS, Plascjak PS, Beck B, Goldman C, Brechbiel MW, Waldmann TA. Blood. 2006;108:1007–1012. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-11-4757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waldmann T. Leuk Lymphoma. 2003;44(Suppl 3):S107–S113. doi: 10.1080/10428190310001623685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waldmann TA. Nat Med. 2003;9:269–277. doi: 10.1038/nm0303-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zalutsky MR, Pozzi OR. Q J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2004;48:289–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang M, Yao Z, Zhang Z, Garmestani K, Talanov VS, Plascjak PS, Yu S, Kim HS, Goldman CK, Paik CH, et al. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8227–8232. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jurcic JG, Larson SM, Sgouros G, McDevitt MR, Finn RD, Divgi CR, Ballangrud AM, Hamacher KA, Ma D, Humm JL, et al. Blood. 2002;100:1233–1239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Washington, DC: Natl Acad Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pastan I, Lovelace ET, Gallo MG, Rutherford AV, Magnani JL, Willingham MC. Cancer Res. 1991;51:3781–3787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Schwarz UP, Plascjak P, Beitzel MP, Gansow OA, Eckelman WC, Waldmann TA. Nucl Med Biol. 1998;25:89–93. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(97)00165-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yordanov AT, Garmestani K, Zhang M, Zhang Z, Yao Z, Phillips KE, Herring B, Horak E, Beitzel MP, Schwarz UP, et al. Nucl Med Biol. 2001;28:845–856. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(01)00257-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mirzadeh S, Brechbiel MW, Atcher RW, Gansow OA. Bioconjug Chem. 1990;1:59–65. doi: 10.1021/bc00001a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kobayashi H, Wu C, Yoo TM, Sun BF, Drumm D, Pastan I, Paik CH, Gansow OA, Carrasquillo JA, Brechbiel MW. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:829–836. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]