Abstract

Context: Athletic trainers are in positions of leadership.

Objective: To determine self-reported leadership practices of head athletic trainers (HATCs) and program directors (PDs).

Design: Cross-sectional study.

Setting: Respondents' academic institutions.

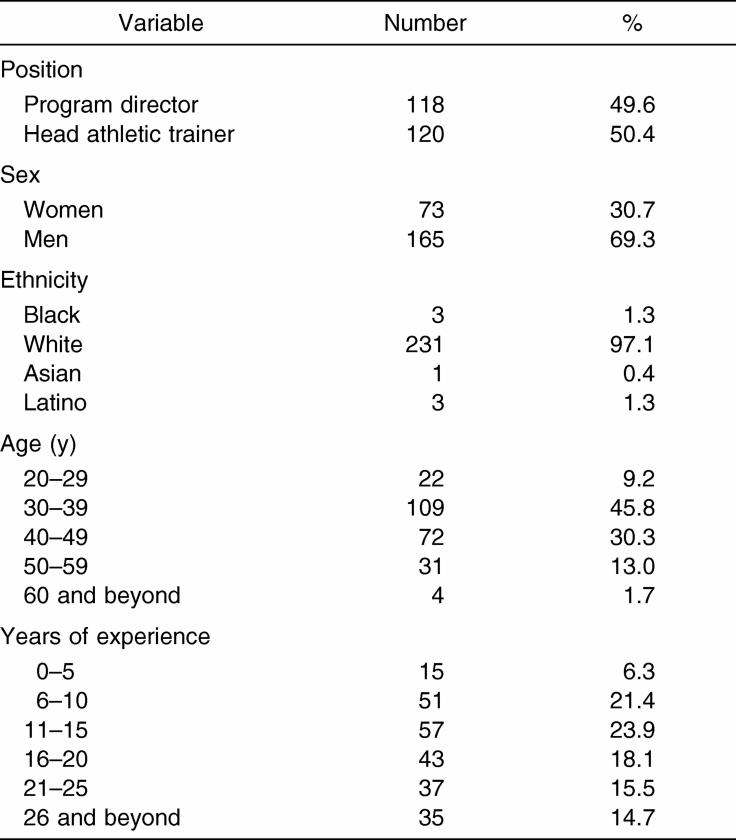

Patients or Other Participants: A total of 238 athletic training leaders completed the Leadership Practices Inventory. Of these, 50.4% (n = 120) were HATCs and 49.6% (n = 118) were PDs; 69.3% (n = 165) were men and 30.7% (n = 73) were women; almost all respondents (97.1%, n = 231) were white. Respondents typically reported having 11 to 15 years of experience as an athletic trainer (n = 57, 23.9%) and being between the ages of 30 and 39 years (n = 109, 45.8%).

Main Outcome Measure(s): Categories of leadership behaviors (ie, Model, Inspire, Challenge, Encourage, and Enable) were scored from 1 (almost never) to 10 (almost always). Item scores were summed to compute mean category scores. We analyzed demographic information; used t ratios to compare the data from athletic training leaders (PDs and HATCs) with normative data; compared sex, age, position, ethnicity, and years of experience with leadership practices; and computed mean scores.

Results: Athletic training leaders reported using leadership behaviors similar to those of other leaders. The PDs reported using inspiring, challenging, enabling, and encouraging leadership behaviors more often than did the HATCs. No differences were found by ethnicity, age, years of experience, or leadership practices.

Conclusions: Athletic training leaders are transformational leaders. Athletic training education program accreditation requirements likely account for the difference in leadership practices between PDs and HATCs.

Keywords: management, leadership style, transformational leadership, Leadership Practices Inventory, survey research

Key Points

Athletic training leaders reported using leadership behaviors similar to those of leaders in other professions.

Athletic training program directors used different leadership behaviors than head athletic trainers used.

Differences in leadership behaviors between program directors and head athletic trainers may be due to education program accreditation requirements.

Leadership is the process of influencing people to accomplish goals.1 Good leadership skills have been shown to increase productivity,2 to improve the work environment,3 to reduce burnout,4,5 and to increase employee satisfaction.3,4,6,7 Leadership has been studied in a variety of professions ranging from business to nursing.8,9 Although the context of leadership changes with each group studied, the construct of leadership remains constant. Effective leaders have the ability to get things done by influencing others.

Leadership skills are important for athletic trainers.10 The Role Delineation Study for the Entry-Level Athletic Trainer11 conducted by the Board of Certification identifies leadership as one of the roles of the certified athletic trainer. According to the study, athletic trainers are responsible for managing human resources to provide efficient and effective health care and educational services.11 Employers also are aware of the need for leadership from athletic trainers and look for leadership skills when hiring them.12 In addition, program directors report the opportunity to lead as one of the most beneficial aspects of their job.13

By virtue of their responsibilities, head athletic trainers (HATCs) and program directors (PDs) are in positions of leadership. Accreditation standards require that the PD provide adequate leadership for the program.14,15 Head athletic trainers are expected to develop and administer a health care system that ensures quality health care while maintaining compliance with governing standards (eg, National Collegiate Athletic Association) and school policies.

Because leadership is integral to the roles and responsibilities of athletic trainers, we need to understand the leadership practices of athletic trainers. Although leadership has been extensively studied in many contexts and within many populations,8,9 to date very little research has been conducted on leadership in athletic training. Five articles dealing with some faction of leadership (eg, job satisfaction, career pathway) have been published in the Journal of Athletic Training.12,13,16–18 Of these 5 articles, only 2 have focused specifically on leadership.17,18 The authors of both manuscripts used research from other disciplines to make inferences regarding athletic training. To date, no original research has been conducted on the leadership practices of athletic trainers.

Without knowing the current leadership practices of athletic trainers, we cannot determine if those in positions of leadership are actually practicing sound leadership behaviors. Therefore, the primary purposes of our study were to determine self-reported leadership practices of HATCs and PDs at Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs (CAAHEP)–accredited institutions and to compare the leadership practices of athletic training leaders (ie, PDs and HATCs) with those of leaders in other fields. A subsequent purpose of this research was to determine which survey technique (mail, e-mail, Web) was preferred by respondents. Determining the preferred survey technique will assist those administering future surveys by saving time and effort.

METHODS

The institutional review board granted permission to conduct this research. We reviewed the list of CAAHEP-accredited undergraduate entry-level athletic training programs in November 2004 from the CAAHEP Web site.19 From this list, we recorded the school, the PD's name, and the PD's e-mail address. This review yielded 298 accredited undergraduate entry-level athletic training PDs. We then reviewed the Web page for each of these schools to determine the HATCs. Names and e-mail contact information of the HATCs were added to our database. Some schools had a single person listed as PD and HATC; some schools did not have an HATC listed. Other HATCs could not be found or determined. Our final list of athletic training leaders (PDs and HATCs) totaled 553. This group was contacted via e-mail and was asked to complete the Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI) developed by Kouzes and Posner.20

In an e-mail message, we informed participants of the study and asked them to participate. They were informed that participation was voluntary and that by completing the survey, they were giving their consent to participate. Participants were provided with 3 means of completing the survey: complete a Web-based survey, respond to the survey included with the e-mail message, or request a copy of the survey via US mail. Two weeks after the initial electronic mailing, we sent a follow-up email to all potential participants to increase the response rate.

Instrument

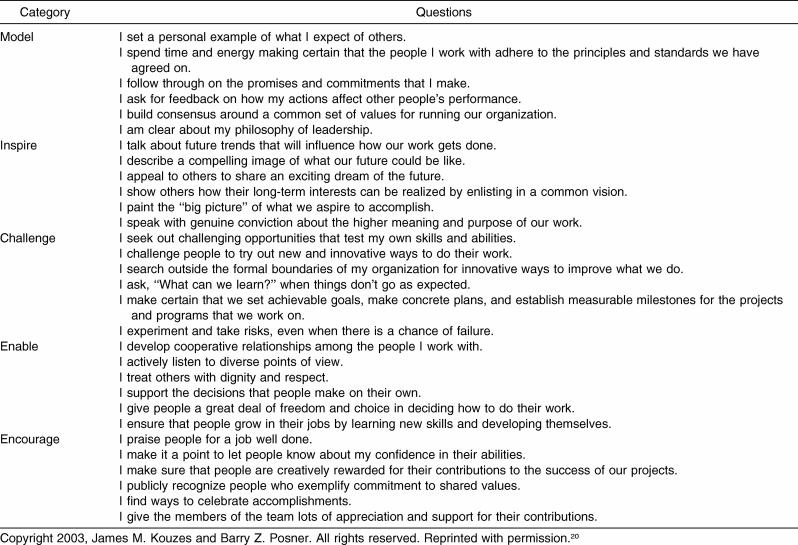

The LPI contains 30 statements categorized into 5 leadership practices: Modeling the Way (Model), Inspiring a Shared Vision (Inspire), Challenging the Process (Challenge), Enabling Others to Act (Enable), and Encouraging the Heart (Encourage). Each leadership practice is defined by 6 leadership behaviors posed in the form of a statement (Table 1). The LPI has been administered to more than 350 000 people in a variety of organizations, disciplines, and demographic backgrounds over more than 15 years. Respondents used to validate the LPI include nurses, engineers, professors, bankers, home health care providers, community leaders, and others.9 The LPI is reliable with high internal consistency (Cronbach α= .75 to .87), regardless of demographic characteristics or organizational features. The LPI is a valid predictor of leadership effectiveness with content and construct validity (regression analysis, F = 318.88 [degrees of freedom not reported], P < .0001, adjusted R2 = .756).5,9 Permission to use the survey was granted by the authors of the LPI, and copyright information was acknowledged on the instrument.

Table 1. Leadership Categories and Questions on the Leadership Practices Inventory.

Respondents were asked to independently rate their behavior regarding the extent to which they engage in each leadership behavior using the following scale: 1 = almost never, 2 = rarely, 3 = seldom, 4 = once in a while, 5 = occasionally, 6 = sometimes, 7 = fairly often, 8 = usually, 9 = very frequently, 10 = almost always. In addition, we added athletic training–specific demographic information to gain an understanding of the background of the respondents. Respondents were asked to indicate their employment position, sex, ethnicity, age, and years of experience. The survey was piloted to a convenience sample of athletic trainers to ensure that the directions and format were clear and that the Web survey worked as expected. After the pilot test, we made minor adjustments in the presentation of the survey directions without changing the original, validated LPI instrument. Pilot data were removed from the Web database, and the survey was sent to the athletic training leaders at colleges and universities with CAAHEP-accredited undergraduate entry-level athletic training programs.

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed the data using SPSS (version 10.0; SPSS Inc; Chicago, IL). The frequency of use of each survey format (mail, e-mail, Web) was recorded. Multiple χ2 analyses were performed to analyze demographic information, item scores within each category were summed to compute category scores, and t ratios were used to compare data from PDs and HATCs with normative data. Category mean scores were determined for PDs and HATCs. A multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was calculated to compare position, sex, ethnicity, age, and years of experience with leadership practices. A 2 (position: PD, HATC) × 5 (category: Model, Inspire, Challenge, Enable, Encourage) MANOVA was used to compare the category mean scores of PDs and HATCs. If the MANOVA identified a significant difference, a discriminant function was performed. The significance level was set at α ≤ .05 due to the exploratory nature of this research in athletic training.

RESULTS

Of the 553 surveys that were mailed electronically, 33 did not reach the recipients due to e-mail failure or incorrecte-mail address. This left a potential participant pool of 520. Of the potential participants, 238 (46%) completed and returned the survey. Of the total responses, 226 (95%) responded via Web-based survey, 12 (5%) responded via e-mail, and 0 (0%) responded via US mail. In the completed surveys, 118 subjects (49.6%) reported PD as their primary job, and 120 subjects (50.4%) reported HATC as their primary job (Table 2). The PDs were older than the HATCs (χ24, P = .01), with a greater percentage of PDs in the age category of 40 to 49 years (PDs, n = 43 [36.44%], versus HATCs, n = 29 [24.17%]).

Table 2. Respondents′ Demographic Information.

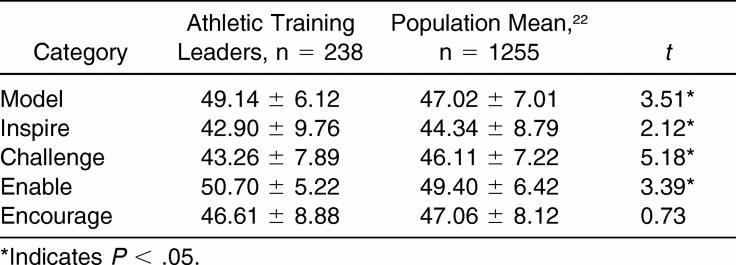

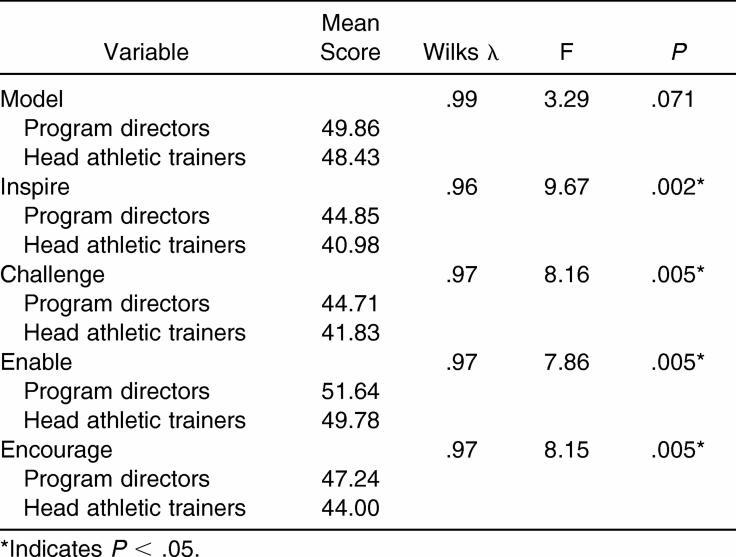

Compared with normative data, athletic training leaders self-reported higher LPI scores on modeling and enabling behaviors and lower scores on inspiring and challenging behaviors (Table 3).21 Athletic training leaders self-reported no difference in frequency of using encouraging behaviors when compared with leaders in other fields (eg, nurses, home health care providers, engineers).9 The PDs reported using inspiring, challenging, enabling, and encouraging leadership behaviors more often than the HATCs did (Table 4). No differences were found for the demographic variables of ethnicity, age, years of experience, or leadership practices. However, a difference was noted between sex and leadership practices; male and female athletic trainers did not differ on the leadership practices in the Inspire category, but women reported more frequently engaging in the Model, Challenge, Enable, and Encourage categories (Wilks λ= .90, P = .002).

Table 3. Comparison of Athletic Training Leaders Self-Reported Leadership Behaviors on the Leadership Practices Inventory With Normative Population Means (Mean ± SD).

Table 4. Mean Leadership Practices Inventory Category Scores of Respondents Based on Position (Program Directors, n = 118; Head Athletic Trainers, n = 120).

DISCUSSION

Athletic training PDs and HATCs perform leadership tasks when they influence people as part of their job responsibilities.11,14 To some extent, all athletic trainers, regardless of position responsibilities, influence the people with whom they work. For these reasons, leadership is an important area of study for athletic trainers. The LPI measures the frequency of use of effective leadership behaviors. It was developed as a result of studying the best practices of leaders in a variety of industries.9 The higher the score on the LPI, the more frequently a person is using effective leadership behaviors. We chose the LPI as our leadership assessment tool for the following reasons:

The LPI presents specific leadership behaviors (eg, “I set a personal example of what I expect of others”), so that the user can respond to and learn from specific criteria rather than ill-defined constructs.

The behaviors included in the LPI characterize the construct of transformational leadership. This allows comparison with a wide range of literature.

The LPI has been administered to a variety of leaders. The normative data available allow a comparison of athletic training leaders' behaviors with those of leaders in other fields.

Researchers22 have discussed whether the LPI measures transformational behaviors exclusively or if it also measures transactional behaviors. The consensus appears to be that the LPI measures transformational behaviors only4,5 and, in general, can be used as a guide to measure transformational leadership.23 Transformational leaders are future focused and set high standards for themselves and others.22 Transformational leaders gain the trust of others by mentoring, encouraging, and empowering those with whom they work.24 These leaders facilitate organizational change and high levels of performance because they transform attitudes, values, and behaviors by communicating a shared vision.5 As a result of this people-focused leadership style, subordinates are more satisfied with their jobs6 and are more productive.4 Transformational leadership encourages leading by molding the attitudes and values of people to fit a single, common vision. Athletic trainers work in environments that easily can become hectic and disorganized due to the volume of patients they serve and constituents with whom they communicate. Patients, coaches, parents, administrators, students, the media, and others add to the work-related stress on the athletic trainer and have the potential to change the daily routine of an athletic trainer. Sound transformational leadership practices allow the athletic trainer to provide order to chaos and to lead people in a single direction. Transformational leadership behaviors, therefore, can help improve the efficiency of athletic training services.

In contrast to transformational leaders, transactional leaders do not adjust the system but work within the framework provided to them. They do not attempt to motivate, model, encourage, enable, challenge, or inspire people. The transactional leader attempts to use extrinsic rewards of money and promotions.5,22 As a result, the transactional leader is less effective in influencing people to accomplish goals.

Athletic Training Leaders Versus Other Leaders

In completing their leadership roles, athletic training leaders exhibit leadership behaviors similar to those of leaders in other fields. Athletic training leaders reported using modeling and enabling behaviors more than other leaders, inspiring and challenging behaviors less than other leaders, and encouraging behaviors to the same extent as other leaders (Table 3). Leaders learn their leadership behaviors from reflecting on their own experiences, observing the experiences of others, and learning through formal education. It is likely that athletic training leaders did not learn all their leadership behaviors from their entry-level experiences. Although physical resource management is part of entry-level education for athletic trainers, human resource leadership is beyond that scope and was likely not an integral part of the athletic training leaders' entry-level education.25 However, this deficit does not necessarily indicate a lack of preparation at the entry level. Experience and continued education can prepare people for leadership. The fact that athletic training leaders practice similar leadership behaviors as other leaders indicates that athletic training leaders are well prepared for their leadership roles. One reason that athletic trainers exhibit effective leadership behaviors similar to those of leaders in other fields could be that athletic training is a “people profession.” The focus on people, with all the benefits and difficulties of working with others, may carry over to positive leadership practices in which athletic trainers influence people. If athletic trainers are proficient at empathizing with others, the rating of leadership behaviors on the LPI would increase, because the LPI presents leadership behaviors that focus on human interaction. This focus of leadership is typically characterized as transformational and also is considered more effective than transactional leadership.9,22,24

Athletic training leaders likely were elevated to their positions because they practiced leadership behaviors or exhibited the potential to lead. Effective leadership is important to the profession of athletic training, because leaders can positively influence job satisfaction and perception of the importance of a job.4 Effective leaders also help to reduce the level of perceived stress of athletic trainers.26 In a profession in which long hours and lack of control can lead to burnout, leaders are essential to fostering a positive work environment that minimizes turnover. Athletic training leaders appear to be practicing the behaviors that positively influence people and the work environment.

Program Directors Versus Head Athletic Trainers

Although the personal attribute of caring for people may explain why athletic training leaders are similar to other leaders, job responsibilities likely explain the difference between PDs and HATCs. The PDs reported more frequently practicing inspiring, challenging, enabling, and encouraging behaviors than did the HATCs (Table 4). The HATC is charged with providing health care services to patients. The PD is charged with developing students into professionals. In completing their tasks, these 2 groups of athletic training leaders have different structures, constraints, and motivators. The environment in which leaders operate influence their leadership behaviors.24 Administrative skills are viewed as important by athletic training leaders but change with the perspective of the respondent. For example, those who serve as PDs perceived administration skills as more important than did those academics who do not serve as PDs.10 The non-PD educators identified research tasks as more important than program administration tasks. This is evidence that athletic trainers' views of the importance of tasks are influenced by their job responsibilities. Because employment tasks influence leaders' views of what is important, leadership behaviors are likely to be influenced by position responsibilities.

The academic environment is very structured, assessment conscious, and future focused. The accreditation process necessitates developing a mission for the athletic training program. In formulating and following the mission, the PD influences people, plans for future issues and trends, and molds the curriculum as needed. With changes in athletic training education over the past 5 to 10 years, PDs have continuously monitored and adjusted to change. Thus, PDs have had an opportunity and the stimulus to exhibit transformational leadership behaviors. Individual HATCs may exhibit these transformational leadership behaviors, but the position does not have the same operational structure as that of a PD. No external agency is requiring continuous review of athletic training services. A guiding mission and an assessment plan is not required of athletic training services. The HATCs also may be so focused on handling daily tasks that they do not focus on future trends to the same extent that the PDs do.

Another explanation for the observed differences in leadership behaviors of PDs and HATCs could be that people with different leadership practices gravitate toward different positions. The HATCs may exhibit fewer transformational leadership skills as defined by the LPI, because they practice a set of leadership skills that allows them to be successful in their role. A match of personal qualities with positional responsibilities is very important for job success and personal satisfaction. We did not ask why the respondents chose their current positions. Future researchers could evaluate more extensively the reasons why athletic training leaders chose their career paths. This could help explain the difference between leadership practices of PDs and HATCs.

Demographic Variables and Leadership Behaviors

Ethnicity, age, and years of experience were not associated with differences in leadership behaviors. Although the PDs in our sample were older than the HATCs were, with more PDs reporting ages of 40 to 49 years, PDs did not report more years of experience than athletic trainers did. More experienced leaders typically described using LPI-identified leadership behaviors more often than did less experienced leaders.27 Experience is synonymous with age in the literature,26 so it is difficult to interpret our results indicating that PDs were older but did not have more years of experience than did athletic trainers. Further research is needed to determine if age or experience influences the leadership practices of athletic trainers.

The number of minority respondents in our sample (7 of 238) was not great enough to examine the behaviors of leaders of different ethnic backgrounds. Although we have no reason to suspect differences exist among athletic training leaders of different ethnic backgrounds, we have too few data to make any inferences. The LPI has been administered to more than 350 000 leaders and is reported to be suitable for all leadership situations and a variety of leadership positions.9 We expect that because these data come from a variety of leaders, a variety of ethnicities was represented in the data pool. Authors of follow-up studies should look at leadership behaviors of athletic training leaders with various ethnic backgrounds. This may help to determine the influence of the person and his or her background versus the influence of the position responsibilities when examining leadership behaviors.

Multiple investigators4,21,23 have examined the relationship between leadership behaviors and sex. One category in which women typically report higher scores is the Encourage category.21 It has been postulated27 that women focus on building relationships with their subordinates, whereas men focus on the vision and the tasks that need to be accomplished. Our findings indicate that female athletic training leaders engaged more often in modeling, challenging, and encouraging behaviors than did male athletic training leaders. We cannot explain this difference. Our sample included 165 men and 73 women. Most of the women (67%, n = 49) were PDs. Because of the heterogeneous groups compared, some of the difference may have been due to the position responsibilities of the PDs rather than the different sexes of the respondents. Our sample does not allow us to make conclusive statements about the differences in leadership behaviors of male and female athletic trainers. Further research needs to be conducted to explore more thoroughly male and female athletic trainer leadership practices.

Recommendations

Leadership behaviors are learned through our experiences, by observing the experiences of others, and through formal education.23 Studying leadership improves leadership practices.27 All athletic trainers, whether they serve as PDs, HATCs, or in another role, are in positions to influence others. Because all athletic trainers have the potential to influence people, athletic training educators should include at least an introduction to leadership styles and practices in the entry-level athletic training curriculum.

Leadership is a complex, multidimensional construct. Although the LPI is a sound research tool with which to study leadership, limitations exist with any single tool. We present an initial assessment of the leadership practices of 2 groups of athletic training leaders, but leadership needs to be more extensively studied in athletic training. Other instruments should be used to more completely define the leadership practices and abilities of athletic trainers.

We assessed self-reported leadership behaviors. Athletic training leadership skills should be studied from multiple perspectives in order to further our knowledge of athletic training leadership practices. Peer, subordinate, and supervisor perceptions of athletic training leaders may differ from self-reported perceptions. Other leader groups also should be explored. For example, the leadership positions within the National Athletic Trainers' Association and other athletic training–related organizations should be reviewed.

A vast majority of respondents of this study preferred responding via a Web-based survey. Web-based surveys are much less expensive and provide a good method of guaranteeing anonymity. We recommend that future researchers use Web-based surveys to reduce cost and to encourage respondent participation.

CONCLUSIONS

Athletic trainers exhibit leadership behaviors similar to those of leaders in other fields. These leadership behaviors are transformational and help to improve the quality of the work environment. The accreditation process likely influences the leadership practices of PDs. Leaders need to be acutely aware of their behaviors in order to influence the actions of others through modeling, inspiring, challenging, enabling, and encouraging. Accreditation provides the framework for leaders to act and also gives the authority that PDs need to influence others. Accreditation likely serves as a unifying mission for the faculty. Although HATCs practiced leadership behaviors similar to those of leaders in other fields, they did not report using leadership behaviors to the same extent as did PDs. This might be because their jobs are not tightly connected to an external review process and because of the leadership opportunities PDs have as part of their roles as faculty members.

REFERENCES

- Huber DL, Maas M, McCloskey J, Scherb CA, Goode CJ, Watson C. Evaluating nursing administration instruments. J Nurs Admin. 2000;30:251–272. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200005000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer ALJ, Steyer JM. Transformational leadership and objective performance in banks. Appl Psychol. 1998;47:397–420. [Google Scholar]

- Webster L, Hackett RK. Burnout and leadership in community mental health systems. Adm Policy Ment Health. 1999;26:387–399. doi: 10.1023/a:1021382806009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manning TT. Gender, managerial level, transformational leadership, and work satisfaction. Women Manage Rev. 2002;17:207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau AE, McGilton K. Measuring leadership practices of nurses using the Leadership Practices Inventory. Nurs Res. 2004;53:182–189. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200405000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medley F, Larochelle DR. Transformational leadership and job satisfaction. Nurs Manage. 1995;26:64JJ–64LL. doi: 10.1097/00006247-199509000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moss R, Rowles CJ. Staff nurse job satisfaction and management style. Nurs Manage. 1997;28:32–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House RJ, Aditya RM. The social scientific study of leadership: quo vadis? J Manage. 1997;23:409–474. [Google Scholar]

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Practices Inventory: theory and evidence behind the five practices of exemplary leaders. Available at: http://www.theleadershipchallenge.com. Accessed May 9, 2005.

- Hertel J, West TF, Buckley WE, Denegar CR. Educational history, employment characteristics, and desired competencies of doctoral-educated athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2001;36:49–56. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Board of Certification. Role Delineation Study for the Entry-Level Athletic Trainer. 5th ed. Omaha NE: Board of Certification; 2004.

- Kahanov L, Andrews L. A survey of athletic training employers' hiring criteria. J Athl Train. 2001;36:408–412. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Judd MR, Perkins SA. Athletic training education program directors' perceptions on job selection, satisfaction, and attrition. J Athl Train. 2004;39:185–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs. Standards and guidelines for an accredited educational program for the athletic trainer. Available at: http://www.caahep.org. Accessed May 9, 2005.

- Commission on Accreditation of Athletic Training Education. Standards for the accreditation of entry-level athletic training education programs. 2005. Available at: http://www.jrc-at.org/html/caate_standards.html. Accessed October 24, 2005.

- Leard JS, Booth C, Johnson JC. A study of career pathways of NATA curriculum program directors. J Athl Train. 1991;26:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer LP. Athletic training clinical instructors as situational leaders. J Athl Train. 2002;37((suppl 4)):S261–S265. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nellis SM. Leadership and management: techniques and principles for athletic training. J Athl Train. 1994;29:328–335. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Accreditation of Allied Health Education Programs. Accredited entry-level athletic training education programs. Available at: http://www.caahep.org/programs.aspx. Accessed November 30, 2004.

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. Leadership Practices Inventory (LPI). 3rd ed. Available at: http://media.wiley.com/assets/463/75/lc_jb_norms2003.pdf. Accessed November 1, 2005.

- Willer AM. Profile, Barriers, and Leadership Behaviors of Women Campus Recreation Directors [dissertation] La Verne, CA: University of La Verne; 2002.

- Fields DL, Herold DM. Using the leadership practices inventory to measure transformational and transactional leadership. Educ Psychol Measure. 1997;57:569–576. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LM, Posner BZ. Exploring the relationship between learning and leadership. Leadership Organ Dev J. 2001;22:274–280. [Google Scholar]

- Eagly AH, Johannesen-Schmidt MC. The leadership styles of women and men. J Soc Issues. 2001;57:781–798. [Google Scholar]

- Athletic Training Educational Competencies. 3rd ed. Dallas, TX: National Athletic Trainers' Association; 1999.

- Hendrix AE, Acevedo EO, Hebert E. An examination of stress and burnout in certified athletic trainers at Division I-A universities. J Athl Train. 2000;35:139–144. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau AE. Building nurse leader capacity. J Nurs Adm. 2003;33:624–626. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200312000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]