Abstract

Development of CD8+ T-cell responses targeting tumor-associated antigens after autologous stem cell transplantations (ASCTs) might eradicate residual tumor cells and decrease relapse rates. Because thymic function dramatically decreases with aging, T-cell reconstitution in the first year after ASCT in middle-aged patients occurs primarily by homeostatic peripheral expansion (HPE) of mature T cells. To study antigen-specific T-cell responses during HPE, we performed syngeneic bone marrow transplantations (BMTs) on thymectomized mice and then vaccinated the mice with peptides plus CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides (CpGs) in incomplete Freund adjuvant and treated the mice with systemic interleukin-2 (IL-2). When CD8+ T-cell responses were measured ex vivo, up to 9.1% of CD8+ T cells were specific for tumor-associated epitopes. These large T-cell responses were generated by synergism between CpG and IL-2. When we injected mice subcutaneously with tumor cells 14 days after BMT and then treated them with peptide + CpG-containing vaccines plus systemic IL-2, survival was increased and tumor growth was inhibited in an epitope-specific manner. Depletion of CD8+ T cells eliminated epitope-specific antitumor immunity. This is the first report to demonstrate that CD8+ T-cell responses capable of executing antitumor immunity can be elicited by CpG-containing vaccines during HPE.

Introduction

The T-cell–dependent graft-versus-malignancy effect that occurs after allogeneic stem cell transplantations demonstrates that clinically important anticancer immunity can be achieved.1–4 Recent advances in tumor immunology offer hope that potent tumor-antigen–specific T-cell responses can also be generated in the autologous setting.5–8 One way to decrease relapse rates after autologous stem cell transplantations (ASCTs) may be to administer vaccines that are capable of generating potent T-cell responses against tumor-associated antigens as soon as possible after transplantation, when disease burden is lowest.

Cytotoxic cancer therapies such as chemotherapy and radiotherapy cause depletion of T cells.9–13 After T-cell depletion, T-cell reconstitution takes place by 2 different pathways.14,15 One pathway is generation of naive T cells by the thymus.11,14 The second pathway is homeostatic peripheral expansion (HPE), which is defined as the dramatic mitotic expansion of mature T cells present in T-cell–depleted hosts.14–16 T-cell repertoires produced by HPE can be skewed toward antigens present in T-cell–depleted hosts.14,16

Most cancer patients are middle aged or older, and thymopoiesis dramatically decreases with increasing age.10,17 As determined by measurement of T-cell receptor excision circles (TRECs) in healthy humans, production of T cells by the thymus decreases by approximately 95% between age 25 years and age 60 years.17 Within the first 6 to 12 months after ASCT or T-cell–depleting chemotherapy, T-cell recovery in adult patients primarily occurs by HPE.10,11 If anticancer vaccines are to be effective for most cancer patients within the first year after ASCT, the vaccines must be able to elicit responses from T-cell populations undergoing reconstitution by HPE.

Many factors might limit the effectiveness of anticancer vaccination in hosts undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE. T cells undergoing HPE might have a greater than normal susceptibility to apoptosis.18,19 T-cell populations generated by HPE from a limited starting number of T cells have restricted T-cell receptor (TCR) diversity and might be limited in the variety of antigens to which they can respond.10,20 T cells from patients after ASCT have impaired function as measured by in vitro assays.9,19 Clinically, numerous investigators have reported prolonged immunodeficiency after ASCT manifested by an increased incidence of viral infection,21–23 and patients who have undergone ASCT have a decreased ability to respond to certain types of vaccination.9,24,25

Despite the potential obstacles to vaccination after ASCT, relapse is the most common cause of death after ASCT,13,26 and development of anticancer vaccination strategies that are effective in the setting of immunodeficiency after ASCT is an important goal. There is a lack of previous work aimed at optimizing vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-cell responses in thymus-deficient hosts undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE. One way to model the middle-aged or elderly patient with severely limited thymic function10,17 is to conduct experiments with thymectomized mice.14 As in middle-aged and elderly cancer patients in the first year after ASCT, T-cell reconstitution in thymectomized mice that receive lethal-dose irradiation followed by syngeneic bone marrow transplantation (BMT) takes place primarily by HPE.14

Oligodeoxynucleotides containing unmethylated CpG motifs (CpGs) are potent vaccine adjuvants that can increase vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-cell responses in mice5,6,27–29 and in humans.30 The use of CpG-containing vaccines in hosts undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE has not previously been studied. Although IL-2 can induce T-cell proliferation,31 IL-2 has been only modestly effective as a single-agent vaccine adjuvant in mice,32–35 and IL-2 has not been effective at enhancing CD8+ T-cell responses elicited by peptide vaccines in humans.36,37 Tyrosinase-related protein 2 (TRP-2) is expressed by normal murine melanocytes and the poorly immunogenic B16F1 melanoma cell line. Amino acids (aa's) 180 to 188 of TRP-2 form an immunogenic MHC class I–presented epitope.8,38 We previously reported that synergism between CpG and IL-2 dramatically increased vaccine-elicited TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses in T-replete mice.39 In addition, a vaccination regimen containing both CpG and IL-2 inhibited growth of B16F1 in an epitope-specific manner while omission of either CpG or IL-2 from this regimen abrogated the epitope-specific tumor growth inhibition.39 Based on this work, we hypothesized that peptide vaccination regimens incorporating CpG and IL-2 would generate large epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses that could eradicate tumor cells in thymectomized mice undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE after syngeneic BMT. We found that peptide vaccination regimens containing the combination of CpG and IL-2 could elicit large numbers of tumor-antigen–specific CD8+ T cells from T-cell populations that were undergoing reconstitution by HPE and that these CD8+ T cells were effective therapy for 2 different murine tumors in the early posttransplantation period. These results indicate a potential clinical role for anticancer vaccination during HPE and demonstrate the ability of vaccination with MHC class I–presented epitopes to shape the T-cell repertoire during HPE.

Materials and methods

Mice and tumor cells

C57BL/6 mice that had undergone suction thymectomy at 4 to 6 weeks of age (Taconic, Germantown, NY) were used for all experiments described in this paper. Thymectomy was confirmed by visual inspection after all experiments. C57BL/6 mice that had not undergone thymectomy were the source of donor cells for BMT. All animal studies were approved by the National Cancer Institute Center for Cancer Research Animal Care and Use Committee. B16F1 melanoma (H-2b) and EL4 lymphoma cells (H-2b) were purchased from ATCC (Manassas, VA). The TC-1 tumor cell line (H-2b) was a gift from Dr TC Wu (Johns Hopkins University).40

Bone marrow transplantations

Thymectomized bone marrow transplant recipient mice were lethally irradiated with 10 Gy 137Cesium γ-radiation using a Gamma Cell 40 irradiator (MDS Nordion, Ottawa, ON). The next morning, spleens and bone marrow cells were collected. CD3+ splenocytes were enriched from donor splenocytes by negative selection using mouse T-cell enrichment columns (R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN). After the enrichment process, a mean of 88% (range, 80%-91%) of the cells were CD3+ (data not shown). Recipient mice that had been irradiated the previous day were injected by tail vein with 1 × 106 CD3-enriched splenocytes and 5 × 106 BM cells.

In some experiments, mice were reconstituted with transplant grafts that were depleted of CD8+ T cells. CD4-enriched splenocytes were obtained by passing splenocytes over a CD4-enrichment column (R&D systems). The resulting CD4-enriched splenocytes averaged 95% CD3+CD4+ with 0.3% CD3+CD8+ cells. CD8+ cells were depleted from BM cells using CD8a microbeads (Miltenyi, Auburn, CA). After this treatment, a mean of 0.15% of BM cells were CD3+CD8+. In CD8-depleted BMT experiments, mice were irradiated, and the next day they were injected with 644 000 CD4-enriched splenocytes and 5 × 106 CD8-depleted BM cells. The chosen number of CD4-enriched splenocytes (644 000) were injected because this was the average number of non-CD3+CD8+ cells contained in the CD3-enriched splenocytes used to reconstitute mice in the standard BMT experiments.

Vaccine ingredients

Amino acids (aa's) 180 to 188 of TRP-2 (TRP-2180-188)6,8,38 and aa's 257 to 264 of the ovalbumin protein (OVA257-264)5 form immunogenic epitopes that are presented by H-2 Kb. Aa's 49 to 57 of the human papillomavirus E7 protein (E749-57)41 and aa's 366 to 374 of the influenza A nucleoprotein (NP366-374)33 form epitopes that are presented by H-2 Db. Peptides were synthesized and purified to 95% purity (Biopeptide LLC, San Diego, CA). Human recombinant IL-2 with a specific activity of 5 × 106 international units (IU)/mg was obtained from the National Cancer Institute Biological Resources Branch. Sterile CpG 182642 in Tris-EDTA (TE) buffer purchased from Coley Pharmaceutical Group (Wellesley, MA) was used in our experiments. Incomplete Freund adjuvant (IFA) was purchased from Sigma (St Louis, MO).

Vaccine preparation

Each vaccine injection consisted of 25 μg CpG and 50 μg TRP-2180-188 in IFA. The volume of all vaccine injections was 100 μL. When CpG was eliminated in experiments, it was replaced with TE buffer. When IL-2 was administered, 40 000 IU was injected 2 times per day intraperitoneally. This regimen of IL-2 has been shown by others to increase the antitumor efficacy of dendritic cell vaccines.43 In some experiments, control buffer that contained human serum albumin and mannitol in PBS was injected in place of IL-2 as a control.

All vaccination regimens used in our experiments consisted of a series of priming vaccinations followed by a boost vaccination. Priming vaccinations were given as a series of 3 injections with 3 days between injections. The first and third priming vaccines were given subcutaneously at the base of the tail; the second priming vaccination was administered subcutaneously on the left side. Boost vaccinations were given at the base of the tail subcutaneously 8 days after the final priming vaccination.

Antibodies

These antibodies from BD Pharmingen (San Diego, CA) were used: anti-CD44 (clone IM7). anti-CD3ϵ (clone 145–2C11), anti-IFNγ (clone XMG1.2), anti-CD11c (clone HL3), anti-I A/E (clone 2G9), and purified anti-CD16/CD32 (clone 2.4G2). Anti-CD8 clone KT-15 (Coulter, Birmingham, United Kingdom) was used in tetramer experiments, and anti-CD8α (clone CT-CD8a) from Caltag (Burlingame, CA) was used in all other experiments.

Intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS) experiments

The percentage of splenic CD8+ T cells that were specific for TRP-2180-188 was determined by stimulating splenocytes with peptides followed by intracellular cytokine staining (ICCS). Mice were killed; splenocytes were red blood cell (RBC) depleted and suspended at 3.5 × 106 live cells/mL. For each mouse, 2 tubes were prepared, one tube contained 1 × 106 EL4 cells that had been pulsed for 3 hours with 20 μg/mL TRP-2180-188, and the other tube contained 1 × 106 EL4 cells that had been pulsed for 3 hours with 20 μg/mL OVA257-264. Next, 3.5 × 106 splenocytes and 1 μL Golgi Plug (BD Pharmingen) were added to each tube. All tubes were incubated at 37°C for 6 hours. The cells were then washed and surface staining for CD3 and CD8 was performed. The cells were then permeabilized and stained for intracellular IFNγ according to the instructions for the Cytofix/Cytoperm kit (BD Pharmingen). For each mouse, a tube containing splenocytes stimulated with TRP-2180-188–pulsed EL4 cells and another tube containing splenocytes stimulated with OVA257-264–pulsed EL4 cells were acquired. Analysis was performed with Cellquest software (Becton Dickinson, Mountain View, CA). The percentage of CD8+ T cells that were specific for TRP-2180-188 was calculated as the percentage of CD3+CD8+IFNγ+ events with TRP-2180-188 stimulation minus the percentage of CD3+CD8+IFNγ+ events with OVA257-264 stimulation. ICCS assays to measure E749-57–specific responses were performed in the same manner except that the EL4 cells were pulsed with 0.1 μg/mL of either E749-57 or NP366-374.

Quantitation of the absolute number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells

RBC-depleted splenocytes from vaccinated mice were prepared. Trypan blue was used for dead cell discrimination, and live cells were counted. The cells were stained with anti-CD3 and anti-CD8. 7-AAD (7-amino actinomycin D; BD Pharmingen) was added for dead cell exclusion. A region enclosing all live cells was analyzed for dual expression of CD3 and CD8. The percentage of live cells expressing both CD3 and CD8 was multiplied by the total number of live splenocytes to determine the absolute number of splenic CD3+CD8+ cells. The absolute number of splenic CD8+ T cells that were specific for TRP-2180-188 was determined by multiplying the absolute number of CD3+CD8+ splenocytes by the percentage of splenic CD8+ T cells that were specific for TRP-2180-188, which was determined during the ICCS assay.

Quantitation of CD8+ T-cell responses with TRP-2180-188-Kb tetramers

To measure TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses, single cell suspensions of splenocytes were stained with TRP-2180-188-Kb tetramers (Coulter) along with anti-CD8 (clone KT15; Coulter). Cells were also stained with anti–I-A/I-E, anti-Ly6G, and 7-AAD to exclude MHC class II–bearing cells, granulocytes, and dead cells, respectively.

Tumor therapy experiments

B16F1 or TC-1 tumor cells were used in tumor therapy experiments. Tumor cells were rapidly proliferating with a viability of greater than 95% at the time of injection. Mice were injected with tumor cells subcutaneously on the right side. The total number of mice needed for both the treatment and control groups was injected with tumor cells, and the mice were randomly distributed to either the treatment group or the control group. Tumor size was measured with calipers every 3 days. The longest length and the length perpendicular to the longest length were multiplied to obtain the tumor size (area) in mm2. When the tumor size reached 200 mm2 or ulceration developed, the mice were killed.

Measurement of TRP-2180-188-specific CD8+ T-cell responses at tumor sites

Mice underwent BMT and were injected with B16F1. Mice were vaccinated with CpG plus either TRP-2180-188 or OVA257-264 in IFA, and IL-2 was administered. Twenty days after initiation of vaccination, tumors were excised, and a single cell suspension of tumor cells was formed. The tumor suspension was RBC-depleted with ACK lysis buffer. Cells were suspended in CM at 3.5 × 106 live cells/mL. For each mouse, one stimulation culture was prepared by adding 20 μg TRP-2180-188 to 1 mL cell suspension, and another stimulation culture was prepared by adding 20 μg OVA257-264 to 1 mL cell suspension. Golgi plug was added to each stimulation culture. Stimulation cultures were incubated for 5 hours. Intracellular cytokine staining for IFNγ was performed, and the percentage of CD8+ T cells that was specific for TRP-2180-188 was calculated as described under ICCS experiments.

TC-1 tumor growth in CD8-depleted mice

Some experiments assessed therapy of TC-1 in mice that had been depleted of CD8+ cells. Anti-CD8 antibody 2.43 (500 μg; National Cell Culture Center, Minneapolis, MN) was injected on days 14, 15, 16, 23, 30, and 37 after BMT. Day 14 after BMT was the day of tumor injection. This regimen eliminated 95% of CD3+CD8+ splenocytes. In experiments that used 2.43 for CD8 depletion, a control group was included that received injections of ChromPure rat IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME) in place of 2.43.

Statistical analysis

Groups were compared using the 2-tailed Mann-Whitney test. In cases in which 3 or 4 groups were compared (Figure 3), P < .01 should be considered statistically significant according to the Bonferroni correction. Otherwise, P < .05 should be considered statistically significant. Unless otherwise stated, graphs show the mean and standard error of the mean. Two to 3 experiments of each type were conducted, and the results of all experiments were combined for graphical presentation and statistical analysis.

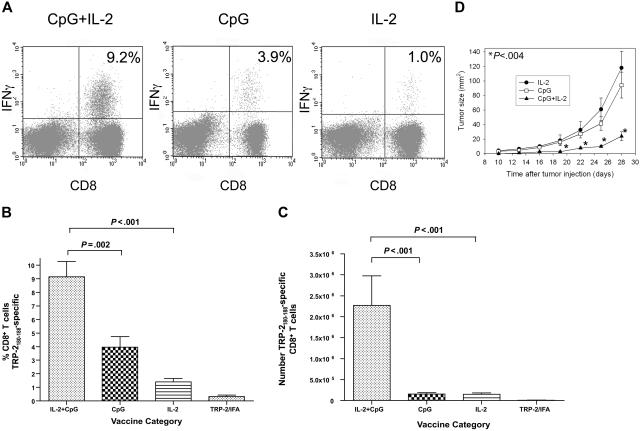

Figure 3.

Synergism between IL-2 and CpG increases the magnitude of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses after BMT. (A) Examples are shown of CD8+ T-cell responses in tumor-bearing mice that received either the vaccination regimen described in Figure 2A that consisted of TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines and systemic IL-2 or TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines with control injections substituted for IL-2 or TRP-2180-188 in IFA without CpG but with systemic IL-2. Vaccination was initiated 14 days after BMT. Peptide stimulation and ICCS were performed as in Figure 2. The percentage of CD8+ T cells that produced IFNγ in response to TRP-2180-188 is shown on each plot. (B) The regimen consisting of TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines, and systemic IL-2 elicited larger TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses as a percentage of total CD8+ T cells than regimens with IL-2 omitted, CpG omitted, or both IL-2 and CpG omitted (n = 8-10 mice per group). (C) The regimen consisting of TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines and systemic IL-2 generated larger absolute numbers of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells than regimens with IL-2 omitted, CpG omitted, or both IL-2 and CpG omitted (n = 8-10 mice per group). (D) Mice underwent BMT and 14 days later they were injected with 100 000 B16F1 cells subcutaneously. The mice were then randomly divided into 3 groups. Starting on the same day as tumor injection, each group received 1 of 3 regimens: TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines and systemic IL-2 (CpG+IL-2), TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines without IL-2 (CpG), or TRP-2180-188 in IFA without CpG but with systemic IL-2 (IL-2). The tumor size of the CpG + IL-2 group was significantly smaller than either of the other 2 groups (P < .004) at the indicated (*) time points (n = 12 mice per group).

Results

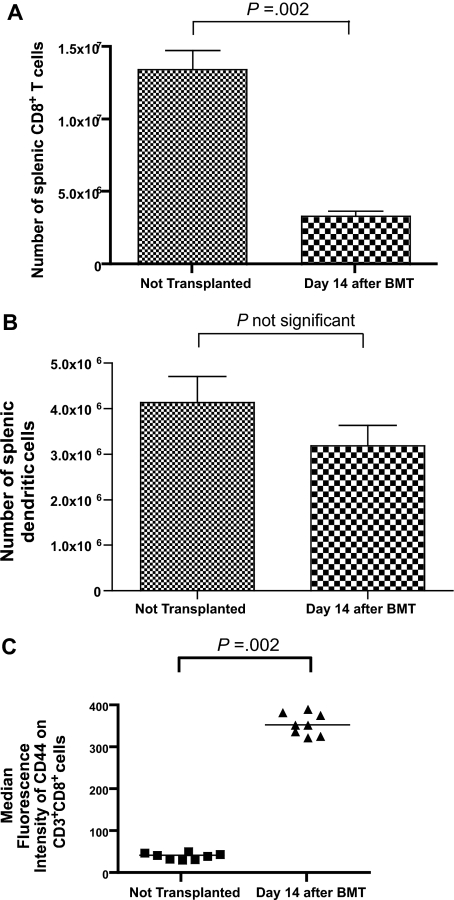

CD8+ T-cell reconstitution is incomplete 14 days after BMT in thymectomized mice

To model T-cell reconstitution by homeostatic peripheral expansion (HPE), we conducted bone marrow transplantations (BMTs) by lethally irradiating thymectomized mice on day −1 and then reconstituting the mice with 1 × 106 T cells and 5 × 106 bone marrow cells on day 0. The T-cell dose of 1 × 106 T cells was selected because it is comparable on a weight adjusted basis with the dose of T cells contained in human peripheral blood stem cell transplant grafts.44,45 Fourteen days after BMT, splenic CD3+CD8+ cells had recovered to 25% of the levels detected in nonirradiated thymectomized mice (Figure 1A). In contrast, by day 14 after BMT splenic dendritic cells recovered to levels equivalent to those found in nonirradiated thymectomized mice (Figure 1B). Expression of the memory marker CD44 was dramatically increased on the CD3+CD8+ cells of mice that underwent BMT compared with mice that did not undergo transplantation (Figure 1C).

Figure 1.

T-cell reconstitution is incomplete 14 days after BMT. (A) Thymectomized mice received a lethal dose of total body irradiation on day −1 and then were injected with 1 × 106 purified T cells and 5 × 106 BM cells on day 0. (A) On day 14 after BMT, the number of splenic CD3+CD8+ cells had recovered to 25% of the number detected in thymectomized mice that did not undergo irradiation and BMT (BMT, n = 13; no BMT, n = 8). (B) The number of splenic dendritic cells in mice 14 days after BMT was similar to the number of splenic dendritic cells in mice that had not undergone transplantation (BMT, n = 7; no BMT, n = 8). Dendritic cells were defined as cells expressing H-2 I-A and CD11c. (C) CD44 expression was increased on CD3+CD8+ cells after BMT (n = 8 mice per group).

Vaccination regimens containing IL-2 and CpG can generate large tumor-antigen–specific CD8+ T-cell responses during T-cell reconstitution by HPE

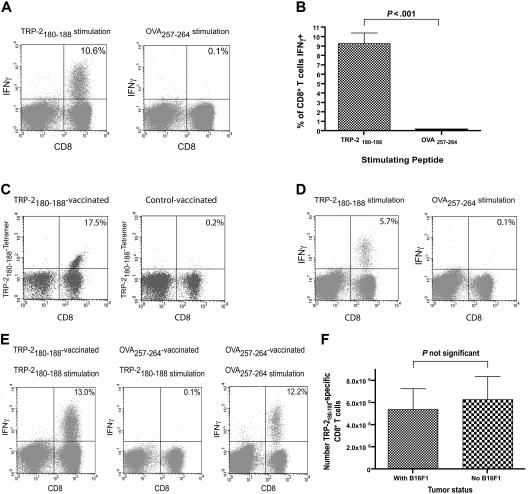

We administered TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines and IL-2 to B16F1 tumor-bearing thymectomized mice that had undergone BMT to test our hypothesis that epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses could be elicited from T-cell populations undergoing reconstitution by HPE after BMT. Large, functional, epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were elicited by TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 when vaccination was initiated 14 days after BMT (Figure 2A-B). The CD8+ T-cell responses elicited by TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 were epitope specific because when splenocytes from vaccinated mice were tested in ICCS assays on day 33 after BMT, a mean of 9.3% of CD8+ T cells produced IFNγ in response to TRP-2180-188 while only 0.1% of CD8+ T cells produced IFNγ in response to the negative control peptide OVA257-264. TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were also detected by TRP-2180-188-Kb tetramers in mice that received TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 after BMT (Figure 2C). When we administered TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 beginning on the same day as BMT (day 0) and measured T-cell responses on day 19 after BMT by ICCS, 5.5% of CD8+ T cells were TRP-2180-188 specific (n = 8 mice, data not shown). CD8+ T-cell responses generated by TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 persisted for at least 25 days after the final vaccination (Figure 2D). When B16F1 tumor-bearing mice were vaccinated with OVA257-264 + CpG and treated with IL-2 they did not generate TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses despite the fact that B16F1 expresses TRP-2 (Figure 2E). In addition, the presence of B16F1 did not affect the number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells generated by TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 (Figure 2F).

Figure 2.

Large TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses can be generated by vaccination after BMT. (A) Large TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses, but minimal OVA257-264–specific responses, were detected in mice that received TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines. Mice underwent BMT as described in Figure 1. On day 14 after BMT, 100 000 B16F1 cells were injected. On days 14, 17, and 20 after BMT, priming vaccines containing TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA were administered. IL-2 was given on days 21 to 23. On day 28 after BMT, a boost vaccine that was identical to the priming vaccines was administered, and IL-2 was given on days 29 to 32. On day 33 after BMT, the mice were killed. Splenocytes were stimulated ex vivo for 6 hours with EL4 cells pulsed with either TRP-2180-188 or OVA257-264, and ICCS for IFNγ was performed. Plots are gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. The percentage of CD3+CD8+ cells that were positive for IFNγ is shown on each plot. Results from one representative mouse are shown. (B) In mice that received vaccines containing TRP-2180-188 + CpG and systemic IL-2, a mean of 9.3% of CD3+CD8+ splenocytes produced IFNγ in response to TRP-2180-188, but only 0.1% of CD3+CD8+ splenocytes produced IFNγ in response to the negative control peptide OVA257-264 (n = 10 mice per group). (C) TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were detected 33 days after BMT by TRP-2180-188-Kb tetramers in mice treated as described in (A). A representative example of 7 mice is shown. (D) TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were detected 25 days after the final vaccination in mice that were vaccinated and treated with IL-2 as described in (A). A representative example of 6 mice tested by ICCS assay is shown. (E) Mice underwent BMT, were vaccinated with peptide + CpG–containing vaccines, and received IL-2 as described in (A). One group was vaccinated with TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines and another group was vaccinated with OVA257-264–containing vaccines. Both groups had B16F1 injected on the same day as the first vaccination (day 14). On day 33, when all mice had palpable tumors, the mice were killed. Splenocytes were stimulated for 6 hours with either TRP-2180-188 or OVA257-264, and ICCS was performed. A representative example of CD8+ T-cell responses detected after ex vivo TRP-2180-188 stimulation of splenocytes from tumor-bearing TRP-2180-188–vaccinated mice is shown. Representative examples are also shown of CD8+ T-cell responses detected in splenocytes from tumor-bearing OVA257-264–vaccinated mice after ex vivo stimulation with either TRP-2180-188 or OVA257-264. Ten TRP-2180-188–vaccinated and eight OVA257-264–vaccinated mice were tested. Plots are gated on CD3+ lymphocytes. The percentage of CD3+CD8+ cells that produced IFNγ is shown on each plot. (F) Mice underwent BMT as described in Figure 1. The mice were then divided into 2 groups. One group was injected with 100 000 B16F1 cells on day 13 after BMT and the other group was not injected with tumor cells. Both groups then received TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines on days 13, 16, 19, and 27 after BMT. IL-2 was administered on days 20 to 22 and days 28 to 31 after BMT. On day 32 after BMT, TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were measured by ICCS assay as described in panel A. The presence of B16F1 did not affect the number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells generated by the vaccination regimen (n = 8 mice per group).

IL-2 and CpG synergize to dramatically increase TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses during T-cell reconstitution by HPE

We administered TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with systemic IL-2 or this regimen with either CpG or IL-2 omitted. The regimen that included both IL-2 and CpG elicited a mean TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell response that was greater than the sum of the mean responses elicited by the regimen containing CpG without IL-2 and the regimen containing IL-2 without CpG. Synergism between IL-2 and CpG was evident whether TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were measured as a percentage of total CD8+ T cells or as an absolute number (Figure 3). The antitumor activity of the different regimens correlated with the number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells that each regimen generated. The TRP-2180-188 vaccination regimen containing both CpG and IL-2 was more effective than regimens with either CpG or IL-2 omitted at inhibiting growth of B16F1 (Figure 3D).

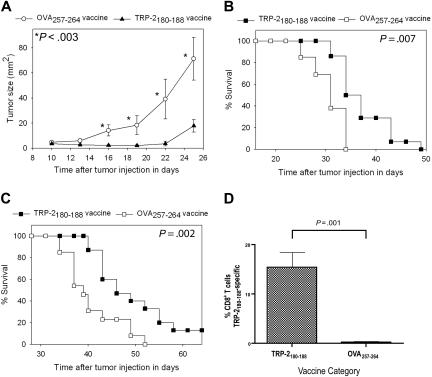

An epitope-specific inhibition of tumor growth and increase in survival occurs after administration of TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines and IL-2 in the setting of HPE after BMT

After demonstrating that IL-2 and CpG synergized to generate large TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses after BMT, we hypothesized that these CD8+ T-cell responses could mediate antitumor immunity in mice undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE. Because CpG is known to inhibit tumor growth by an NK-cell–dependent mechanism42 and because our aim was to study CD8+ T cells, our tumor therapy experiments were designed to measure epitope-specific antitumor effects. We injected mice with tumor cells and then divided the mice into 2 groups. One group was treated with TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines and IL-2; another group was treated with vaccines containing the negative control peptide OVA257-264 and CpG along with IL-2. Aside from the different peptides, both groups were treated identically; therefore, differences in tumor growth between the 2 groups are epitope specific.

For our first series of tumor therapy experiments, we used the poorly immunogenic and rapidly proliferating B16F1 melanoma. B16F1 expresses almost undetectable levels of cell surface H-2 Kb, the MHC class I molecule that presents TRP-2180-18846,47; therefore, B16F1 is a very difficult test for a vaccination regimen that elicits CD8+ T-cell responses. This tumor arose spontaneously in a C57BL/6 mouse, and it has not been genetically altered, so it may be a more realistic model of human malignancy than many murine tumor lines.33,38 Mice underwent BMT and then 14 days later they were injected with 100 000 B16F1 cells subcutaneously. Next, the mice were treated with TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 or vaccines containing the negative control peptide OVA257-264 and CpG along with IL-2. Mice that received TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines had a decreased rate of tumor growth (Figure 4A) and increased survival (Figure 4B) compared with mice that received OVA257-264–containing vaccines. In the next series of experiments, mice were injected with 10 000 B16F1 tumor cells (a 10-fold lower dose than in previous experiments) 14 days after BMT and then treated with either TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 or regimens that were identical except that the negative control peptide OVA257-264 replaced TRP-2180-188. Survival was increased in mice that received TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines compared with mice that received OVA257-264–containing vaccines, and a fraction of TRP-2180-188–vaccinated mice survived tumor-free for more than 6 months (Figure 4C). To measure CD8+ T-cell responses at tumor sites, we established B16F1 tumors in mice after BMT and then administered TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 or OVA257-264 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2. When we measured TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses at tumor sites, 15.4% of intratumoral CD8+ T cells were specific for TRP-2180-188 in mice that received TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines while negligible TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were detected in mice that received OVA257-264–containing vaccines (Figure 4D).

Figure 4.

Epitope-specific inhibition of tumor growth and increased survival occurred after TRP-2180-188 + CpG vaccination combined with IL-2 in thymectomized mice after BMT. (A) Mice underwent BMT on day 0. Mice were injected subcutaneously with 100 000 B16F1 cells on day 14 after BMT. Also on day 14 after BMT, the regimen described in Figure 2A consisting of peptide + CpG + IFA vaccines and IL-2 was initiated. Tumor growth was inhibited in mice that received TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines compared with mice that were treated identically except that the negative control peptide OVA257-264 replaced TRP-2180-188 in vaccines. A statistically significant difference (P < .003) between the 2 groups occurred at the indicated (*) time points (TRP-2180-188 vaccinated, n = 14; OVA257-264 vaccinated, n = 13). (B) In the mice described in (A), overall survival was increased in mice that received vaccines containing TRP-2180-188 compared with mice that received vaccines containing the negative control peptide OVA257-264. (C) Mice underwent BMT on day 0. On day 14, the mice were injected with 10 000 B16F1 cells subcutaneously (a 10-fold lower dose of B16F1 than in the experiments described in A-B). Mice were then vaccinated and treated with IL-2 in an identical fashion as the mice described in (A). Mice that received vaccines containing TRP-2180-188 had increased survival compared with mice that received vaccines containing the negative control peptide OVA257-264. A fraction of mice that received vaccines containing TRP-2180-188 survived long term (greater than 6 months) without evidence of tumors. Both groups were treated identically except for the difference in peptide (TRP-2180-188 vaccinated, n = 15; OVA257-264 vaccinated, n = 13). (D) Mice underwent BMT and were injected with B16F1. One group received TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines and IL-2 as described in Figure 2A, while a second group received identical regimens except that the negative control peptide OVA257-264 replaced TRP-2180-188 in vaccines. TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were detected at tumor sites of mice that received TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines, but not at tumor sites of mice that received OVA257-264–containing vaccines (TRP-2180-188–containing vaccines, n = 7; OVA257-264–containing vaccines, n = 6).

Epitope-specific tumor growth inhibition depends on the presence of CD8+ T cells in the transplant graft

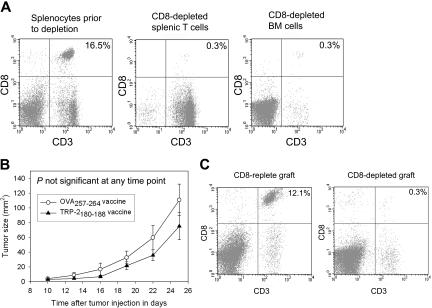

The epitope-specific inhibition of B16F1 tumor growth and increased survival demonstrated in our experiments depended on the presence of the MHC class I–presented peptide TRP-2180-188 in vaccines. This finding indicated that CD8+ T cells were important in causing the antitumor effect. To confirm that CD8+ T cells contained in the transplant graft were responsible for the epitope-specific inhibition of tumor growth, we conducted BMT on thymectomized mice in which CD8+ T cells were depleted from the transplant grafts (Figure 5A). When CD8+ T cells were depleted from the transplant grafts, epitope-specific tumor growth inhibition was abrogated (Figure 5B). When thymectomized mice that had undergone CD8-depleted BMT were killed 42 days after transplantation, minimal numbers of splenic CD8+ T cells were present (Figure 5C).

Figure 5.

Epitope-specific inhibition of B16F1 tumor growth depends on CD8+ T cells contained in the transplant graft. (A) CD8+ cells were depleted from the grafts used to reconstitute mice that underwent BMT. A representative example of splenic T cells and BM cells after CD8 depletion compared with splenocytes from the same mice before depletion is shown. (B) Mice underwent BMT on day 0. Transplantations were conducted identically to the experiments described in Figure 4A except that CD8+ cells were depleted from the spleen and BM cells as shown in 5A. On day 14, 100 000 B16F1 cells were injected subcutaneously. As described in Figure 4, one group received regimens consisting of TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines plus systemic IL-2, and a second group received identical regimens except that the negative control peptide OVA257-264 replaced TRP-2180-188. In contrast to the experiments described in Figure 4, no difference in tumor size was observed in the mice that received vaccines containing TRP-2180-188 compared with the mice that received vaccines containing the negative control peptide OVA257-264 (TRP-2180-188 vaccinated, n = 11; OVA257-264 vaccinated, n = 10). (C) CD8+ T-cell depletion persisted 42 days after BMT (28 days after tumor injection) in the mice described in panel B. The plots show splenocytes from a mouse that was reconstituted with a CD8+ cell–replete graft and a representative example of splenocytes from a mouse that received a graft that was depleted of CD8+ cells.

The absolute number of vaccine-elicited TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells was not different in mice that underwent BMT and mice that did not undergo BMT

We compared the ability of post-BMT mice and mice that did not undergo BMT to generate epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses. Both groups were injected with B16F1, and both groups then received identical vaccination regimens that consisted of TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines and systemic IL-2. In mice that underwent BMT, vaccination was initiated 14 days after BMT. When the T cells of vaccinated mice were analyzed 19 days after initiation of vaccination, mice that did not undergo transplantation had a larger number of CD3+ T cells than mice that underwent BMT (Figure 6A). Because CD8+ T cells made up a larger fraction of total T cells in mice that underwent BMT than in mice that did not undergo BMT (Figure 6B) and because of a statistically not significant trend toward a larger percentage of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells in mice that underwent BMT compared with mice that did not undergo BMT (Figure 6C), the mean absolute number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells was equivalent in mice that underwent BMT and mice that did not undergo BMT (Figure 6D). Consistent with this result, there was not a statistically significant difference in B16F1 growth in mice that underwent BMT and mice that did not undergo BMT (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

The absolute number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+T cells generated by CpG-containing vaccines plus IL-2 did not differ between mice that underwent BMT and mice that did not undergo BMT. On day 0, age-matched thymectomized mice underwent BMT or did not undergo BMT. Both groups of mice were injected with B16F1 on day 14. Starting on day 14, the vaccination regimen described in Figure 2A that consisted of TRP-2180-188 + CpG + IFA vaccines and systemic IL-2 was administered to both the BMT group and the non-BMT group. On day 33, the mice were killed, T cells were enumerated, and TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were measured by ICCS assay as described in Figure 2. (A) Mice that underwent BMT had a smaller number of splenic CD3+ T cells than mice that did not undergo BMT. (B) CD3+CD8+ T cells made up a larger fraction of total CD3+ T cells in mice that underwent BMT than in mice that did not undergo BMT. (C) The percentages of CD8+ T cells that were TRP-2180-188–specific in mice that underwent BMT and in mice that did not undergo BMT are shown. (D) The absolute number of TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T cells was equivalent in mice that underwent BMT and mice that did not undergo BMT. The data described in (A)-(D) were obtained from the same mice (n = 8 mice per group). (E) The B16F1 tumor growth rate was equivalent in mice that underwent BMT and mice that did not undergo BMT (n = 12 mice per group).

Vaccine-elicited E749-57–specific CD8+ T cells can inhibit TC-1 tumor growth in the setting of HPE after BMT

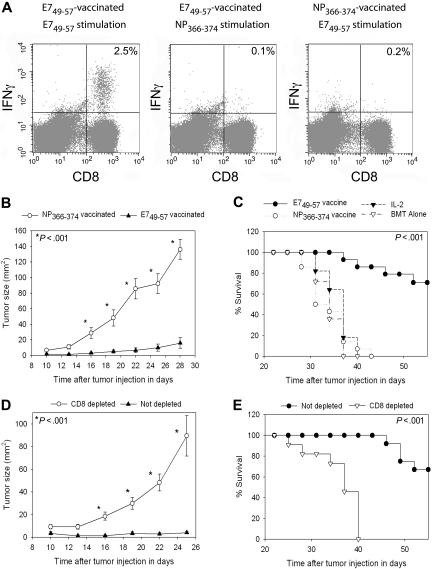

To test the antitumor efficacy of vaccination in the setting of HPE after BMT with a different tumor than B16F1, we used the TC-1 tumor cell line.40 TC-1 expresses the human papillomavirus E7 protein. When we vaccinated TC-1 tumor-bearing mice with the E749-57 peptide plus CpG in IFA and administered IL-2, epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses were elicited against E749-57 that were detected ex vivo (Figure 7A). In TC-1 tumor-bearing mice that were vaccinated with the negative control peptide NP366-374 plus CpG in IFA and treated with IL-2, minimal E749-57–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were detected (Figure 7A). Two groups of mice were injected with TC-1 tumor cells, and 3 days later treatment was initiated with regimens containing either E749-57 and CpG in IFA or the negative control peptide NP366-374 and CpG in IFA. Both groups also received IL-2. Potent epitope-specific inhibition of tumor growth (Figure 7B) and increased survival (Figure 7C) occurred in mice that received E749-57–containing vaccines compared with mice that received NP366-374–containing vaccines. This inhibition of tumor growth was epitope specific because both groups of mice were treated identically except for the different peptides in their vaccines. To conclusively demonstrate that the anticancer effect observed with E749-57 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 was dependent on CD8+ cells, we conducted BMT on 2 groups of mice and challenged both groups with TC-1. CD8+ cells were depleted from one of the groups, while the second group was not depleted. Both groups of mice were vaccinated with E749-57 + CpG + IFA vaccines, and both groups received IL-2. Inhibition of tumor growth depended on CD8+ cells (Figure 7D), and depletion of CD8+ cells decreased survival (Figure 7E).

Figure 7.

TC-1 tumors were effectively treated by peptide + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 during T-cell reconstitution by HPE after BMT. (A) Mice underwent BMT as described in Figure 1. On day 14 after BMT, mice were injected with TC-1 tumor cells, which express the E7 protein. On days 17, 20, 23, and 31 after BMT, the mice were vaccinated with E749-57 + CpG + IFA vaccines or the negative control peptide NP366-374 plus CpG in IFA. IL-2 was administered to both groups on days 24 to 26 and days 32 to 35 after BMT. When CD8+ T-cell responses were measured by ICCS assay on day 36 after BMT in E749-57–vaccinated mice, E749-57–specific CD8+ T-cell responses were detected. Minimal responses against the negative control peptide NP366-374 were detected in E749-57–vaccinated mice. Tumor-bearing mice vaccinated with NP366-374 did not generate E749-57–specific CD8+ T-cell responses. The numbers on the plots are the percentages of CD8+ T cells from mice receiving the indicated vaccines that produced IFNγ in response to ex vivo stimulation with the indicated peptides. (B) Mice underwent BMT and 14 days after BMT the mice were injected with 50 000 TC-1 tumor cells. On days 17, 20, 23, and 31 after BMT, the mice were vaccinated with either E749-57 + CpG in IFA or the negative control peptide NP366-374 plus CpG in IFA. Both groups received IL-2 as described in (A). Aside from the different peptides, both groups were treated identically. A statistically significant difference in tumor size between the 2 groups occurred at the indicated (*) time points (P < .001, n = 14 mice per group). (C) In the same mice described in (B), survival was increased in mice that received vaccines containing E749-57 compared with mice that were treated identically except that their vaccines contained the negative control peptide NP366-374 (P < .001, n = 14 mice per group). (C) also shows the survival of post-BMT mice that were injected with TC-1 cells and then either treated with IL-2 alone on days 24 to 26 and days 32 to 35 after BMT or left untreated (IL-2, n = 11; BMT alone, n = 11). (D) Mice underwent BMT and then received either a CD8-depleting antibody or an isotype-matched control antibody. Mice were injected with 50 000 TC-1 tumor cells 14 days after BMT. Both CD8-depleted mice and mice that were not depleted were vaccinated with E749-57 + CpG in IFA and treated with IL-2 as in (A). Depletion of CD8+ cells led to increased tumor growth (D) and decreased survival (E) (CD8 depleted, n = 11; not depleted, n = 12). In (D), a statistically significant difference in tumor size (P < .001) between the 2 groups occurred at the indicated (*) time points.

Discussion

To study T cells undergoing HPE, we conducted syngeneic BMT on thymectomized mice. After BMT, we injected the mice with tumor cells and then administered a therapeutic vaccination regimen to the mice. We initiated vaccination 14 days after BMT when CD8+ T-cell reconstitution was quantitatively (Figure 1A) and qualitatively (Figure 1C) incomplete. Administration of peptide + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 generated very large epitope-specific CD8+ T-cell responses that were detected ex vivo by intracellular staining for IFNγ and by tetramer staining (Figures 2 and 7). Our results are consistent with previous work that demonstrated the ability of T cells undergoing HPE to respond to stimulation with peptide-MHC complexes.14,16 The absolute number of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells generated by vaccination of T-cell–depleted mice undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE was equivalent to the absolute number of epitope-specific CD8+ T cells generated by vaccination of T-cell–replete mice despite the lower number of total T cells in the T-cell–depleted mice (Figure 6D).

B16F1 is very poorly immunogenic and it expresses very low levels of MHC class I molecules.46,47 The poor immunogenicity of B16F1 is demonstrated by the data presented in Figure 2E. B16F1 tumor-bearing mice did not generate CD8+ T-cell responses against TRP-2180-188 when the mice were vaccinated with the negative control peptide OVA257-264 plus CpG and treated with IL-2 despite the expression of TRP-2 by B16F1. These results show that the immunogenic peptide is a critical component of the vaccine regimens used in these experiments. Similar findings were evident in experiments with the TC-1 tumor (Figure 7A).

Despite the obstacles of T-cell depletion, a poorly immunogenic tumor, and self-tolerance, TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 could consistently inhibit tumor growth and increase survival of mice that were injected with B16F1 on the same day as initiation of vaccination 14 days after BMT (Figure 4). TRP-2180-188--specific CD8+ T cells were present at the tumor sites of mice that received TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines (Figure 4D). The epitope-specific inhibition of B16F1 tumor growth observed with TRP-2180-188 + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 was dependent on CD8+ T cells contained in the transplant graft (Figure 5B). As expected, there was no significant source of CD8+ T cells in thymectomized mice after BMT except the T cells contained in the transplant graft (Figure 5C). Potent CD8+ T-cell–dependent antitumor immunity was also generated against the TC-1 tumor cell line after BMT (Figure 7).

Although others have successfully treated tumors by adoptive transfer of tumor-specific T cells after lymphocyte depletion,7,48 our results demonstrate that peptide + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 can elicit large, functional, tumor-antigen–specific CD8+ T-cell responses from polyclonal T-cell populations undergoing HPE without adoptive transfer of tumor-specific T cells.

Many studies of vaccination after ASCT in humans and syngeneic BMT in mice have focused on CD4+ T-cell and antibody responses.25,49–51 While anticancer therapies that elicit CD4+ T-cell and antibody responses are promising, substantial evidence exists that CD8+ T-cell responses can cause regression of poorly immunogenic tumors in mice6,8,33 and humans.7 Importantly for cancer therapy, CD8+ T-cell reconstitution is much more rapid than CD4+ T-cell reconstitution after T-cell–depleting chemotherapy19,52 or ASCT.9,53 As in the thymectomized mouse model used in our work, when adult humans recover from T-cell depletion, CD8+ T cells make up a larger than normal fraction of total T cells.9,19,52,53 Within 3 months after ASCT in adult humans, CD8+ T-cell numbers return to normal9,53 while CD4+ T-cell recovery to normal levels takes more than one year and is often incomplete.9,10,53

Some previous investigators have studied anticancer vaccination in lymphocyte-depleted mice; however, these investigators used young mice with intact thymic function.49,54,55 Because production of naive T cells by the thymus within the first year after ASCT is minimal in adults older than 50 years, it is important to study vaccination in mice that lack thymic function.10,17 Our work makes an important contribution by demonstrating that potent CD8+ T-cell–mediated antitumor immunity can be generated in the absence of thymic function.

This is the first report of CpG as a vaccine adjuvant in the setting of T-cell reconstitution. The CpG used in our work, CpG 1826, has been shown previously to be a potent T-cell vaccine adjuvant and to have multiple effects that include inducing maturation of dendritic cells and elevating levels of IL-6, IL-12, and TNFα.27,42 Synergism between CpG and IL-2 dramatically increased TRP-2180-188–specific CD8+ T-cell responses in T-cell–depleted mice undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE (Figure 3). CpG 7909 is an oligodeoxynucleotide that is similar to CpG 1826.27,30 CpG 7909 is undergoing clinical trials as a vaccine adjuvant in melanoma patients.30 Peptide vaccines incorporating CpG 7909 have elicited some of the largest vaccine-elicited CD8+ T-cell responses ever reported in humans.30

Because most cancer patients are middle aged or older, they will often have greatly diminished thymic function.10,17 Many cancer patients receive T-cell–depleting chemotherapy or undergo ASCT. The feasibility of administering IL-2 after ASCT26,56 or nonmyeloablative chemotherapy7,57 has been demonstrated. We used IL-2 in our experiments rather than other promising cytokines such as IL-7 or IL-15 because a large amount of clinical experience has been acquired with IL-2 and because IL-2 is already an approved drug. These factors should expedite translation of our findings to clinical trials. Our results that demonstrated the effectiveness of peptide + CpG–containing vaccines combined with IL-2 at mediating antitumor immunity in T-cell–depleted mice undergoing T-cell reconstitution by HPE should encourage clinical trails of vaccination with CpG-containing vaccines combined with IL-2 in T-cell–depleted cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by intramural funding of the National Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: J.N.K. designed research, performed research, collected data, analyzed and interpreted data, drafted the paper, and revised the paper; J.L.S. performed research and revised the paper; C.D.C. performed research and revised the paper; R.E.G. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and revised the paper. C.D.C. and J.L.S. contributed equally to this work.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: James N. Kochenderfer, NIH, 10 Center Dr CRC 3–3288, Bethesda, MD 20892; e-mail: kochendj@mail.nih.gov.

References

- 1.Copelan EA. Hematopoietic stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1813–1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horowitz MM, Gale RP, Sondel PM, et al. Graft-versus-leukemia reactions after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1990;75:555–562. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marmont AM, Horowitz MM, Gale RP, et al. T-cell depletion of HLA-identical transplants in leukemia. Blood. 1991;78:2120–2130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson BD, Becker EE, Truitt RL. Graft-vs.-host and graft-vs.-leukemia reactions after delayed infusions of donor T-subsets. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 1999;5:123–132. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.1999.v5.pm10392958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davila E, Celis E. Repeated administration of cytosine-phosphorothiolated guanine-containing oligonucleotides together with peptide/protein immunization results in enhanced CTL responses with anti-tumor activity. J Immunol. 2000;165:539–547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davila E, Kennedy R, Celis E. Generation of antitumor immunity by cytotoxic T lymphocyte epitope peptide vaccination, CpG-oligodeoxynucleotide adjuvant, and CTLA-4 blockade. Cancer Res. 2003;63:3281–3288. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dudley ME, Wunderlich JR, Robbins PF, et al. Cancer regression and autoimmunity in patients after clonal repopulation with antitumor lymphocytes. Science. 2002;298:850–854. doi: 10.1126/science.1076514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Elsas A, Sutmuller RP, Hurwitz AA, et al. Elucidating the autoimmune and antitumor effector mechanisms of a treatment based on cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 blockade in combination with a B16 melanoma vaccine: comparison of prophylaxis and therapy. J Exp Med. 2001;194:481–489. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.4.481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guillaume T, Rubinstein DB, Symann M. Immune reconstitution and immunotherapy after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 1998;92:1471–1490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hakim FT, Memon SA, Cepeda R, et al. Age-dependent incidence, time course, and consequences of thymic renewal in adults. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:930–939. doi: 10.1172/JCI22492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Age, thymopoiesis, and CD4+ T-lymphocyte regeneration after intensive chemotherapy [see comment]. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:143–149. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199501193320303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Lymphocyte depletion during treatment with intensive chemotherapy for cancer. Blood. 1994;84:2221–2228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sportes C, McCarthy NJ, Hakim F, et al. Establishing a platform for immunotherapy: clinical outcome and study of immune reconstitution after high-dose chemotherapy with progenitor cell support in breast cancer patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2005;11:472–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2005.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mackall CL, Bare CV, Granger LA, Sharrow SO, Titus JA, Gress RE. Thymic-independent T cell regeneration occurs via antigen-driven expansion of peripheral T cells resulting in a repertoire that is limited in diversity and prone to skewing. J Immunol. 1996;156:4609–4616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackall CL, Granger L, Sheard MA, Cepeda R, Gress RE. T-cell regeneration after bone marrow transplantation: differential CD45 isoform expression on thymic-derived versus thymic-independent progeny. Blood. 1993;82:2585–2594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fry TJ, Mackall CL. The many faces of IL-7: from lymphopoiesis to peripheral T cell maintenance. J Immunol. 2005;174:6571–6576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naylor K, Li G, Vallejo AN, et al. The influence of age on T cell generation and TCR diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174:7446–7452. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.11.7446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fry TJ, Christensen BL, Komschlies KL, Gress RE, Mackall CL. Interleukin-7 restores immunity in athymic T-cell-depleted hosts. Blood. 2001;97:1525–1533. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.6.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hakim FT, Cepeda R, Kaimei S, et al. Constraints on CD4 recovery postchemotherapy in adults: thymic insufficiency and apoptotic decline of expanded peripheral CD4 cells. Blood. 1997;90:3789–3798. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mackall CL, Hakim FT, Gress RE. T-cell regeneration: all repertoires are not created equal. Immunol Today. 1997;18:245–251. doi: 10.1016/s0167-5699(97)81664-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reusser P, Fisher LD, Buckner CD, Thomas ED, Meyers JD. Cytomegalovirus infection after autologous bone marrow transplantation: occurrence of cytomegalovirus disease and effect on engraftment. Blood. 1990;75:1888–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuchter LM, Wingard JR, Piantadosi S, Burns WH, Santos GW, Saral R. Herpes zoster infection after autologous bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 1989;74:1424–1427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Whimbey E, Elting LS, Couch RB, et al. Influenza A virus infections among hospitalized adult bone marrow transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1994;13:437–440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gandhi MK, Egner W, Sizer L, et al. Antibody responses to vaccinations given within the first two years after transplant are similar between autologous peripheral blood stem cell and bone marrow transplant recipients. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2001;28:775–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapoport AP, Stadtmauer EA, Aqui N, et al. Restoration of immunity in lymphopenic individuals with cancer by vaccination and adoptive T-cell transfer [see comment]. Nat Med. 2005;11:1230–1237. doi: 10.1038/nm1310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stein AS, O'Donnell MR, Slovak ML, et al. Interleukin-2 after autologous stem-cell transplantation for adult patients with acute myeloid leukemia in first complete remission. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:615–623. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Krieg AM. CpG motifs in bacterial DNA and their immune effects. Ann Rev Immunol. 2002;20:709–760. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.100301.064842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhee EG, Mendez S, Shah JA, et al. Vaccination with heat-killed leishmania antigen or recombinant leishmanial protein and CpG oligodeoxynucleotides induces long-term memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses and protection against leishmania major infection. J Exp Med. 2002;195:1565–1573. doi: 10.1084/jem.20020147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tritel M, Stoddard AM, Flynn BJ, et al. Prime-boost vaccination with HIV-1 Gag protein and cytosine phosphate guanosine oligodeoxynucleotide, followed by adenovirus, induces sustained and robust humoral and cellular immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;171:2538–2547. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Speiser DE, Lienard D, Rufer N, et al. Rapid and strong human CD8+ T cell responses to vaccination with peptide, IFA, and CpG oligodeoxynucleotide 7909. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:739–746. doi: 10.1172/JCI23373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith KA. Interleukin-2: inception, impact, and implications. Science. 1988;240:1169–1176. doi: 10.1126/science.3131876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Melchionda F, Fry TJ, Milliron MJ, McKirdy MA, Tagaya Y, Mackall CL. Adjuvant IL-7 or IL-15 overcomes immunodominance and improves survival of the CD8+ memory cell pool. J Clinical Invest. 2005;115:1177–1187. doi: 10.1172/JCI23134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Overwijk WW, Theoret MR, Finkelstein SE, et al. Tumor regression and autoimmunity after reversal of a functionally tolerant state of self-reactive CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:569–580. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubinstein MP, Kadima AN, Salem ML, Nguyen CL, Gillanders WE, Cole DJ. Systemic administration of IL-15 augments the antigen-specific primary CD8+ T cell response following vaccination with peptide-pulsed dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2002;169:4928–4935. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.9.4928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen W, Reese VA, Cheever MA. Adoptively transferred antigen-specific T cells can be grown and maintained in large numbers in vivo for extended periods of time by intermittent restimulation with specific antigen plus IL-2. J Immunol. 1990;144:3659–3666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rosenberg SA, Yang JC, Schwartzentruber DJ, et al. Immunologic and therapeutic evaluation of a synthetic peptide vaccine for the treatment of patients with metastatic melanoma [see comment]. Nat Med. 1998;4:321–327. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slingluff CL, Jr, Petroni GR, Yamshchikov GV, et al. Immunologic and clinical outcomes of vaccination with a multiepitope melanoma peptide vaccine plus low-dose interleukin-2 administered either concurrently or on a delayed schedule. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:4474–4485. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.10.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bloom MB, Perry-Lalley D, Robbins PF, et al. Identification of tyrosinase-related protein 2 as a tumor rejection antigen for the B16 melanoma. J Exp Med. 1997;185:453–459. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kochenderfer JN, Chien CD, Simpson JL, Gress RE. Synergism between CpG-containing oligodeoxynucleotides and IL-2 causes dramatic enhancement of vaccine-elicited CD8+ T cell responses. J Immunol. 2006;177:8860–8873. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.12.8860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lin KY, Guarnieri FG, Staveley-O'Carroll KF, et al. Treatment of established tumors with a novel vaccine that enhances major histocompatibility class II presentation of tumor antigen. Cancer Res. 1996;56:21–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gendron KB, Rodriguez A, Sewell DA. Vaccination with human papillomavirus type 16 E7 peptide with CpG oligonucleotides for prevention of tumor growth in mice. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:327–332. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.3.327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ballas ZK, Krieg AM, Warren T, et al. Divergent therapeutic and immunologic effects of oligodeoxynucleotides with distinct CpG motifs. J Immunol. 2001;167:4878–4886. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.9.4878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu K, Fields RC, Giedlin M, Mule JJ. Systemic administration of interleukin 2 enhances the therapeutic efficacy of dendritic cell-based tumor vaccines. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:2268–2273. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.5.2268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Verbik DJ, Jackson JD, Pirruccello SJ, Patil KD, Kessinger A, Joshi SS. Functional and phenotypic characterization of human peripheral blood stem cell harvests: a comparative analysis of cells from consecutive collections. Blood. 1995;85:1964–1970. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Weaver CH, Longin K, Buckner CD, Bensinger W. Lymphocyte content in peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected after the administration of recombinant human granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1994;13:411–415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Peter I, Mezzacasa A, LeDonne P, Dummer R, Hemmi S. Comparative analysis of immunocritical melanoma markers in the mouse melanoma cell lines B16, K1735 and S91-M3. Melanoma Res. 2001;11:21–30. doi: 10.1097/00008390-200102000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seliger B, Wollscheid U, Momburg F, Blankenstein T, Huber C. Characterization of the major histocompatibility complex class I deficiencies in B16 melanoma cells. Cancer Research. 2001;61:1095–1099. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gattinoni L, Finkelstein SE, Klebanoff CA, et al. Removal of homeostatic cytokine sinks by lymphodepletion enhances the efficacy of adoptively transferred tumor-specific CD8+ T cells. J Exp Med. 2005;202:907–912. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borrello I, Sotomayor EM, Rattis FM, Cooke SK, Gu L, Levitsky HI. Sustaining the graft-versus-tumor effect through posttransplant immunization with granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF)-producing tumor vaccines. Blood. 2000;95:3011–3019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Davis TA, Hsu FJ, Caspar CB, et al. Idiotype vaccination following ABMT can stimulate specific anti-idiotype immune responses in patients with B-cell lymphoma. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2001;7:517–522. doi: 10.1053/bbmt.2001.v7.pm11669219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hata A, Asanuma H, Rinki M, et al. Use of an inactivated varicella vaccine in recipients of hematopoietic-cell transplants [see comment]. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:26–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa013441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mackall CL, Fleisher TA, Brown MR, et al. Distinctions between CD8+ and CD4+ T-cell regenerative pathways result in prolonged T-cell subset imbalance after intensive chemotherapy. Blood. 1997;89:3700–3707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schlenke P, Sheikhzadeh S, Weber K, Wagner T, Kirchner H. Immune reconstitution and production of intracellular cytokines in T lymphocyte populations following autologous peripheral blood stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2001;28:251–257. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Asavaroengchai W, Kotera Y, Mule JJ. Tumor lysate-pulsed dendritic cells can elicit an effective antitumor immune response during early lymphoid recovery. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:931–936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022634999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ma J, Urba WJ, Si L, Wang Y, Fox BA, Hu HM. Anti-tumor T cell response and protective immunity in mice that received sublethal irradiation and immune reconstitution. Eur J Immunol. 2003;33:2123–2132. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Robinson N, Benyunes MC, Thompson JA, et al. Interleukin-2 after autologous stem cell transplantation for hematologic malignancy: a phase I/II study. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1997;19:435–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Farag SS, George SL, Lee EJ, et al. Postremission therapy with low-dose interleukin 2 with or without intermediate pulse dose interleukin 2 therapy is well tolerated in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia: Cancer and Leukemia Group B study 9420 [erratum appears in Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:3639]. Clin Cancer Res. 2002;8:2812–2819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]