Abstract

The structure and dynamics of a large segment of Ste2p, the G-protein-coupled α-factor receptor from yeast, were studied in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles using solution NMR spectroscopy. We investigated the 73-residue peptide EL3-TM7-CT40 consisting of the third extracellular loop 3 (EL3), the seventh transmembrane helix (TM7), and 40 residues from the cytosolic C-terminal domain (CT40). The structure reveals the presence of an α-helix in the segment encompassing residues 10–30, which is perturbed around the internal Pro-24 residue. Root mean-square deviation values of individually superimposed helical segments 10–20 and 25–30 were 0.91 ± 0.33 Å and 0.76 ± 0.37 Å, respectively. 15N-relaxation and residual dipolar coupling data support a rather stable fold for the TM7 part of EL3-TM7-CT40, whereas the EL3 and CT40 segments are more flexible. Spin-label data indicate that the TM7 helix integrates into DPC micelles but is flexible around the internal Pro-24 site, exposing residues 22–26 to solution and reveal a second site of interaction with the micelle within a region comprising residues 43–58, which forms part of a less well-defined nascent helix. These findings are discussed in light of previous studies in organic-aqueous solvent systems.

INTRODUCTION

G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) constitute a large family of integral membrane proteins of prime biological importance. They are involved in various important physiological processes such as signal transduction associated with cell growth, pain perception, blood pressure control, and sensing of light, odor, and taste (1). Of drugs currently used to treat various pathologies, ∼30% target GPCRs (2,3). Despite the widespread occurrence of GPCRs and the fact that they have been studied intensively during the last two decades, fundamental information concerning their three-dimensional (3D) structure and about the molecular details of ligand binding and signal transduction is still missing. Although more than 1000 GPCRs have been identified, presently only a single high-resolution x-ray structure that for bovine rhodopsin a light-sensing GPCR is available (4). The atomic details of the seven transmembrane helical bundle from this crystal structure have served as a scaffold for modeling of other GPCRs (5), since all members of this superfamily are believed to share a common topology of seven membrane-spanning helices, connected either by extracellular or cytoplasmic loops. The amino and carboxy termini are always located at the extracellular and cytoplasmic side, respectively (6–8). The tremendous difficulties encountered in obtaining refraction-grade crystals of membrane proteins and the large size of their complexes with detergents and lipids complicate structural studies by x-ray crystallography or NMR. Furthermore, expression, purification, and reconstitution in a membrane-mimicking environment are technically extremely demanding, and only slow progress has been made despite intense efforts (9–11).

To address these issues much attention was recently devoted to the study of relatively short peptides corresponding to loops and single transmembrane domains (TMDs) of GPCRs to expand our knowledge on local details of the 3D structure of the intact molecules (12,13). Most of the previous structural investigations on fragments of GPCRs have been limited to fragments containing up to ∼50 residues. Even for these relatively short peptides, only a few high-resolution structures in detergent micelles have been published, indicating the practical difficulties encountered in conducting such biophysical studies.

We have performed intensive studies on individual TMDs of the α-factor receptor (Ste2p) from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (14–20). Signaling by Ste2p, triggered by binding the tridecapeptide-α-factor mating pheromone, results in growth arrest and gene regulation in preparation for sexual conjugation of yeast cells (21). Like other GPCRs, the 431-residue Ste2p contains seven hydrophobic TMDs, with its carboxyl terminus located in the cytosolic milieu. Mutagenesis studies have revealed a key role of the TMDs in α-factor receptor activation. The carboxy terminus was shown to be involved in Ste2p downregulation through endocytosis and in desensitization by phosphorylation (22).

To determine their structure in hydrophobic environments, fragments corresponding to the individual TMDs were studied by circular dichroism (CD), infrared, and NMR spectroscopy in trifluoroethanol (TFE)/water mixtures (19). In three of these domains the α-helices were disrupted by a kink centered around a Pro residue in the case of the sixth and seventh TMDs and around two Gly residues in the case of first TMD. The solubility of constructs corresponding to the third and fourth TMDs was very low, such that they could not be effectively purified by high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), requiring addition of several lysine residues at both termini of the peptides (23). Furthermore, the sixth TMD of Ste2p displayed a high tendency for aggregation on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (16). To minimize sample preparation problems and spectroscopic difficulties resulting from poor solubility, we envisaged synthesizing constructs of the receptor in which appreciable parts of the hydrophilic cytosolic domain were added to the hydrophobic seventh TMD (18). In addition to increasing solubility, the cytosolic extension may aid in the folding of the construct, and information on its structure could be relevant to its biological role in signal transduction and regulation.

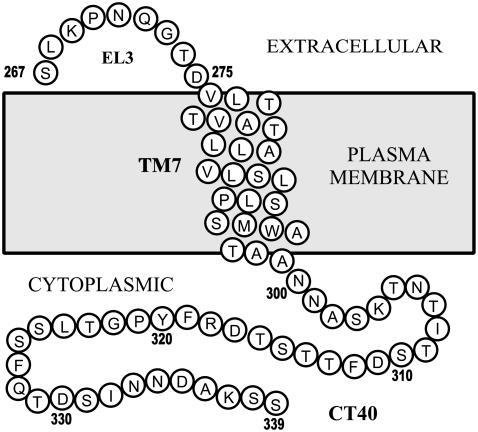

For convenient production of this larger domain, we have chosen a recombinant approach in Escherichia coli. The polypeptide described here is composed of 9 residues of the third extracellular loop (EL3, Ste2p residues 267–275), 24 residues comprising the putative seventh TMD (TM7, Ste2p residues 276–299), and 40 residues of the cytosolic carboxy terminus (CT40, Ste2p residues 300–339) of the Ste2p receptor (residues 1–9, 10–33, and 34–73 of EL3-TM7-CT40, respectively, Fig. 1). The desired 73-residue TMD peptide was expressed as a TrpΔLE fusion protein and liberated from its fusion partner using cyanogen bromide cleavage (20). The recombinant method facilitated expression of EL3-TM7-CT40 in uniformly 15N- or 15N-, 13C-labeled forms required for triple-resonance NMR spectroscopy. Recently we demonstrated that upon addition of 15N-labeled amino acids to rich growth media, peptide selectively labeled with Ala, Ser, or Leu residues with acceptable percentages of isotope cross-labeling (24) were produced.

FIGURE 1.

Cartoon of the region of Ste2p examined in this investigation. EL3, third extracellular loop. TM7, seventh transmembrane helix. CT40, 40 residues of the cytosolic tail.

Herein we report data on the structure and internal backbone dynamics of the multi-domain peptide EL3-TM7-T40 in dodecylphosphocholine (DPC) micelles. The 1H, 13C, and 15N resonances could be assigned to a very large extent. The computed structure, based on restraints from nuclear Overhauser enhancement spectroscopy (NOESY) experiments, reveals the presence of an α-helix in the segment 10–30, corresponding to residues 276–296 of the Ste2p receptor that is disrupted around the internal Pro residue. The internal backbone dynamics derived from 15N relaxation data support the view that the transmembrane (TM) part of EL3-TM7-CT40 is rather stably folded, whereas the cytosolic part is much more flexible. Micelle-integrating spin labels support the conclusion that the TM7 helix integrates into DPC micelles but also demonstrate that motion around the internal Pro site partially brings residues that would be deeply buried in the micelle interior closer to the detergent headgroups. The C-terminal decapeptide of the polypeptide is unstructured, but large segments (e.g., from residues 43–58) with significant propensity for adopting helical conformations exist. The micelle insertion/association topology of the peptide is fully supported by our understanding of amino acid partitioning into the membrane interior or the membrane-water interface. These studies further validate the approach of using fragments of GPCRs as surrogates to probe receptor structure.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

NMR sample preparation

Perdeuterated d38-DPC, perdeuterated MES (2-morpholinoethanesulfonic acid, monohydrate), and deuterated water were purchased from Cambridge Isotopes (Andover, MA). The spin labels 5- and 16-doxylstearates were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) and Gd-DOTA (1,4,7,10-tetraazocyclododecane-N,N-acetic acid) (DOTAREM) from Laboratoire Guerbet (Gonesse, France). All other chemical used were ordered from Fluka (Milwaukee, WI).

For preparation of the 0.5 mM EL3-TM7-CT40 NMR sample, 26.4 mg d38-DPC and 1 mg of peptide were dissolved together in ∼1 ml of hexafluoro-i-propanol (HFIP), the solution was sonicated for 10 min at 50°C and subsequently lyophilized until an oily residue (12–15 h) remained. This mixture was dissolved in 250 μl of 20 mM MES buffer (pH ∼6), 750 μl of water was added, and the solution was lyophilized until dry again. The lyophilized powder consisting of DPC and the peptide was dissolved in 250 μl H2O/D2O (9:1), mixed by vortexing until all of the solid material is dissolved, incubated for 15 min at 37°C, and transferred to a Shigemi NMR tube (Shigemi, Allison Park, PA). The final concentration of d38-DPC was always 300 mM. The EL3-TM7-CT40 concentration used for the 13C- and 15N-resolved NOESY spectra was 0.5 mM. For supporting experiments (e.g., relaxation, spin-label studies etc.), concentrations of 0.1–0.4 mM were used. Samples used for the residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) measurements contained EL3-TM7-CT40 and d38-DPC at concentrations of 0.25 mM and 200 mM, respectively. All NMR measurements were conducted on a Bruker AV700 spectrometer at 310 K using a triple-resonance cryoprobe (Bruker, Billerica, MA).

For the RDC measurements the peptide-micelle complex was oriented in a stretched polyacrylamide gel (25,26). The gel was polymerized from a 4% (w/v) solution of acrylamide and bisacrylamide with a monomer/cross-linker ratio of 37.5:1 (w/w). The dry gel was soaked for 24 h in plain buffer followed by equilibration with a solution of 15N-labeled EL3-TM7-CT40/d38-DPC for 48 h, after which the gel was compressed from 6 mm to a final diameter of 4 mm.

Spin label experiments were performed using 5-doxyl stearic acid, 16-doxyl stearic acid, or Gd-DOTA in separate experiments. Small aliquots of concentrated solutions of 5- or 16-doxylstearate in d3-methanol were dissolved in the solution of the 15N-EL3-TM7-CT40/d38-DPC sample to obtain a final concentration of ∼7 mM of spin label corresponding to slightly more than one spin-label per micelle. In the case of the experiment utilizing Gd-DOTA, an appropriate volume of a 5 mM aqueous solution of Gd-DOTA was lyophilized and the remaining powder mixed with the detergent solution of the peptide resulting in a Gd-DOTA concentration of ∼6 mM. [15N,1H]-heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) spectra in the presence and absence of spin labels were recorded and attenuations were computed from the relative peak volumes in these experiments. In cases of overlap, peak intensities were used instead of peak volumes and severely or completely overlapped residues were generally excluded from the analysis. In all cases, the relative intensity of residue i was computed from the average of residues i − 1, i, and i + 1, whenever this was possible, to reduce the extent of smaller fluctuations.

Cloning, expression, and purification of 15N,13C-labeled EL3-TM7-CT40

The cloning, expression, and isolation of [13C/15N]-EL3-TM7-CT40 {S1LKPN QGTDV L11TTVA TLLAV L21SLPL SSLWA T31AANN ASKTN T41ITSD FTTST D51RFYP GTLSS F61QTDS INNDA K71SS} were carried out using procedures described in the literature (20). EL3-TM7-CT40 selectively labeled with [15N]-alanine, [15N]-leucine, or [15N]-serine was prepared in rich medium containing an excess of the [15N]-labeled amino acid as described by Englander et al. (24).

NMR spectroscopy

Sequence-specific resonance assignment was accomplished based on a set of 15N-resolved proton-proton correlation spectra, e.g., a 40 ms 15N-resolved total correlation spectroscopy (TOCSY) and 75 ms 15N-resolved NOESY (27,28), as well as a set of triple-resonance experiments. Backbone assignment was performed based on a CBCA(CO)NH (29) (1024*40(15N)*128(13C) complex data points: t3max 122 ms, t2max 12.8 ms, t1max 6.1 ms), a HNCACB experiment (30) (1024*64(15N)*128(13C) complex data points: t3max 122 ms, t2max 20.5 ms, t1max 6.1 ms), and a H(CCC)(CO)NH (31) experiment (1024*20(15N)*64(13C) complex data points: t3max 127 ms, t2max 10.9 ms, t1max 8.0 ms). Side chain resonances were assigned based on HCCH-TOCSY experiments (1024*32*64 complex points: t3max 104 ms, t2max 7.9 ms, t1max 9.1 ms) (32,33) using a B1 field of 8.3 kHz for the TOCSY spin-lock as well as from a 70 ms 13C-resolved NOESY experiment. The aromatic ring systems were correlated with β-carbons via the HBCBCGCDHD and HBCBCGCDCEHE experiments introduced by Yamazaki et al. (34). Assignment within the aromatic moieties was done using a 23 ms constant time heteronuclear multiple-quantum coherence (HMQC)-TOCSY experiment (35) in which the proton TOCSY relay was tuned for direct (12 ms) and relayed (40 ms) transfer. Chemical shifts were finally picked in the [15N,1H]-HSQC and the 13.3 ms constant time [13C,1H]-HSQC spectra and indirectly referenced to the water line at 4.63 ppm using the conversion factors of 0.10132900 (15N) and 0.25144954 (13C) (36). All experiments employed pulsed-field gradients.

The extent of amide hydrogen exchange was probed by recording a [15N,1H]-HSQC experiment in which low-power irradiation was applied on the water resonance during the relaxation delay. Peak volumes were determined in this experiment and their values relative to a reference experiment conducted in the absence of irradiation but with otherwise identical parameter computed. 15N-relaxation data were recorded using a proton detected version of the 15N{1H} steady-state nuclear Overhauser effect (NOE) experiment (37). A recycle delay of 2.7 s was used for the 15N{1H} NOE experiment, and 128 scans were recorded per increment.

Data were usually extended by a factor of two using linear prediction in the indirect dimensions and processed within the Bruker spectrometer software TOPSPIN 1.3. Integration of peak volumes was performed within the program SPSCAN. 3JHNα scalar coupling constants were derived from the splitting of the in-phase doublets of [15N,1H]-HSQC peaks using the INFIT algorithm (38) in XEASY (39). Processed data were transferred into the program CARA for data analysis (40).

Structure calculation

Distance restraints were obtained from NOESY spectra recorded with a mixing time of 70 ms either in 90% H2O/10% 2H2O (15N-resolved NOESY) or in 99.9% 2H2O(13C-resolved NOESY). In addition dihedral angle restraints were derived from TALOS (41) using 13C chemical shifts of Cα and Cβ atoms, and further such restraints were added by the CANDID/ATNOS suite of programs. Structures were calculated using a simulated-annealing protocol for molecular dynamics in torsion angle space as implemented in the program CYANA (42,43). The final CYANA calculation was performed with 100 randomized starting structures, and the 20 CYANA conformers with the lowest target function values were selected to present the NMR ensemble. The conformers were analyzed, including calculation of root mean-square deviation (RMSD) values, and figures were prepared within the program MOLMOL (44).

RESULTS

Sample preparation

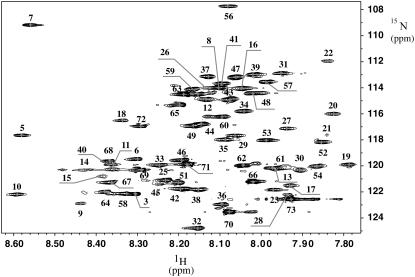

Direct dissolution of EL3-TM7-CT40 in DPC solution resulted in poor quality [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra with little signal, indicating that the peptide was not properly inserted into the micelle. Therefore, the protocol developed by Killian et al. (45) was applied, in which the peptide was dissolved in a 50:50 (v/v) mixture of HFIP/water followed by dilution into micellar solution, lyophilization, and redissolving in pure water. A sample prepared by this protocol resulted in moderate quality [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra in which ∼60 out of the 70 expected backbone resonance peaks were visible. We subsequently modified the protocol to include two steps of lyophilization. The peptide and DPC were initially dissolved in HFIP and lyophilized until an oily residue remained. The latter was taken up in aqueous buffer and thoroughly lyophilized to complete dryness to eliminate residual HFIP. After this procedure reproducible [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra containing the expected 70 peaks could be measured (Fig. 2), indicating that the EL3-TM7-CT40 was well integrated into the DPC micelles. Such samples were sufficiently stable for measurement of 3D and 2D NMR spectra at 310 K and only displayed indications of additional peaks after more than 2 weeks. At that time a spectrum with the original quality could be recovered when the sample was lyophilized and redissolved, but after 3–4 weeks additional signals due to degradation appeared.

FIGURE 2.

[15N, 1H]-HSQC spectrum recorded at 700 MHz, 310 K, on a 0.5-mM sample of the peptide in 300 mM DPC. The sequence-specific assignment has been annotated.

Resonance assignment

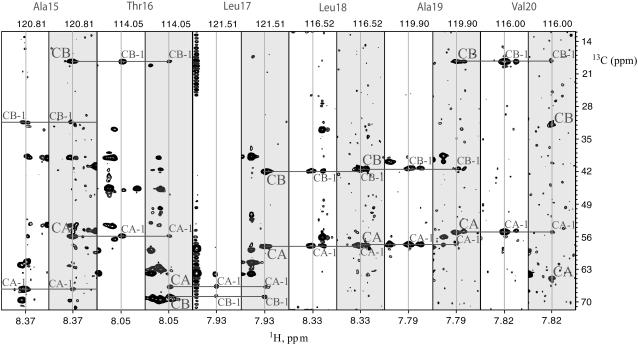

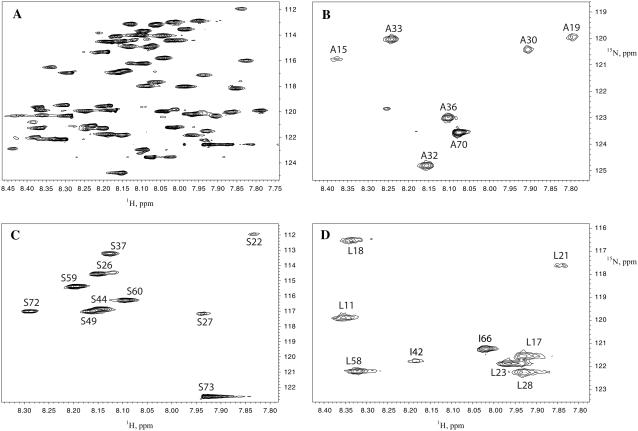

Sequence-specific sequential resonance assignment of EL3-TM7-CT40 was accomplished by triple-resonance NMR spectroscopy using 13C,15N, and 15N uniformly labeled samples. Data evaluation was performed using the recently developed program CARA (40). For backbone assignment 3D HNCACB (30) and CBCA(CO)NH (29) spectra provided the most useful information. In the [15N, 1H]-HSQC spectra we were able to observe over 60 crosspeaks, for which intra- and/or interresidual Cα and Cβ crosspeaks occurred in the HNCACB and CBCA(CO)NH spectra. For the remaining 10 crosspeaks in the [15N, 1H]-HSQC either one or several resonances were missing in the corresponding strips from the HNCACB or CBCA(CO)NH spectra. The unique chemical shifts observed for Gly and Ala residues provided starting points in the assignment process. A set of strips corresponding to the assignment of residues Ala-15 to Val-20 of the TM segment is depicted in Fig. 3 and the completely assigned [15N, 1H]-HSQC spectrum is shown is Fig. 2. Additionally we recorded [15N, 1H]-HSQC spectra on samples of the peptide that were selectively labeled by Ala, Ser, and Leu (see Fig. 4). These data served to confirm the position of corresponding residues in the [15N, 1H]-HSQC spectra despite some cross-labeling of Ile-42 and Ile-66 (Fig. 4). Crosspeaks from Leu-2 and Leu-25 could not be found. We experienced significant difficulties in making assignments for residues 21–28 and 46–51. Due to a lack of correlations in the triple-resonance spectra, no assignments of 1H and 15N resonances corresponding to Leu-2 and Thr-50 could be obtained. To provide an additional check for resonance assignments, which uses further information from the type of side-chain spin systems, we also recorded an H(CCC)(CO)NH experiment (31).

FIGURE 3.

Strips from the 3D CBCA(CO)NH and the HNCACB spectra taking at various amide proton positions displaying the assignment process of the 15N,13C, and 1H chemical shifts of backbone and Cβ atoms. The 15N chemical shift, at which the strip was extracted, is displayed above the strips.

FIGURE 4.

[15N, 1H]-HSQC spectra of selectively labeled constructs. The reference spectrum of 15N-uniformly labeled peptide is shown in panel A. Panels B–D display spectra from Ala, Ser, and Leu residues, respectively.

Hα/Cα crosspeaks from the backbone assignment were subsequently used as anchoring points for further assignment of the aliphatic side chains. Most likely due to short T2 relaxation times of many Cα and Cβ resonances, the HCCH-TOCSY spectra (32,33) were unfortunately of moderate quality only, and we were forced to make extensive use of 15N-resolved TOCSY and NOESY and 13C-resolved NOESY spectra to complete the assignment.

To accomplish assignment of aromatic side chains, two-dimensional (2D) versions of the (HB)CB(CGCD)HD and (HB)CB(CGCDCE)HE experiments (34) were recorded. Assignments of aromatic protons were completed and verified by data from a [1H,1H]-TOCSY relayed constant time [13C,1H]-HMQC experiment (35) and a 13C-resolved NOESY centered at the aromatic carbons. The chemical shifts of all assigned 1H, 13C, and 15N nuclei are listed in the Supplementary Material. The completeness of the backbone and side-chain assignments was over 90% for all resonances. Assignment of labile protons from side chains of Asp, Asn, Gln, Glu, Arg, and Lys was generally not possible.

Determination of the structure of EL3-TM7-CT40

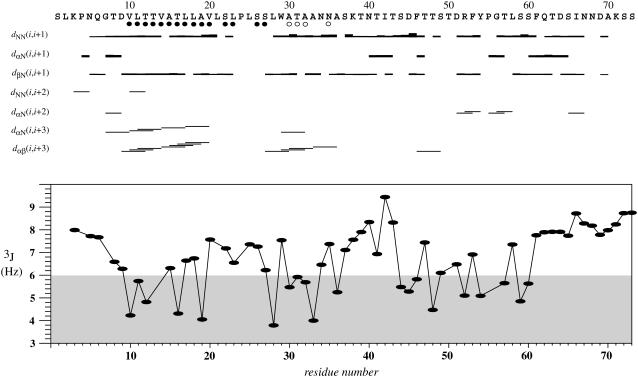

The structure of EL3-TM7-CT40 was determined by solution NMR methods using uniformly 13C-, 15N-, or 15N-labeled 0.5 mM peptide in the presence of 300 mM DPC at pH 6.0. The final structure calculations utilized a total of 1018 meaningful NOE upper distance constraints and 46 angle constraints for the backbone dihedral angles derived from Cα chemical shifts and from 3JHNα scalar couplings. A graphical representation of the restraints used in the structure calculation is presented in Fig. 5. Characteristic medium-range Hα,β(i, i + 3) NOEs have been observed in the regions 10–21 and 29–34. The average CYANA target function value obtained was 1.01 ± 0.10 Å, indicating the presence of only a few minor violations. The average backbone RMSD to the mean coordinates was 11.80 ± 1.74 Å, and no systematic distance constraint violations remained.

FIGURE 5.

(Top) Sequence plot displaying characteristic upper distance restraints along the sequence derived from NOEs. For those residues for which dihedral angle restraints derived from 13C chemical shifts were applied, a solid circle is placed under the residue number when restraining φ in the range of [−120.0.. −20.0°] and ψ to [−120.0.. −20.0°] and for open circles when restraining to the much looser bounds of [−120.0.. 80.0°] for φ and [−100.0.. 60.0°] for ψ. (Bottom) 3JHNα scalar coupling constants as extracted by the INFIT method from the HSQC spectrum. The region containing reduced scalar couplings representative of helical tendencies is shaded.

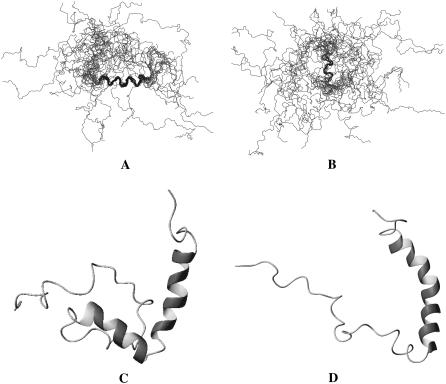

The ensemble of low-energy NMR conformations is depicted in Fig. 6 and displays two helices in the putative TM region of the polypeptide. When individually superimposing backbone atoms from these helical segments, the RMSD values are 0.91 ± 0.33 Å and 0.76 ± 0.37 Å for residues 10–20 and 25–30, respectively. A calculation of secondary structure according to the Kabsch-Sander algorithm (46) reveals that the first α-helix extends from residues 10–22 in 13 of the 20 lowest energy conformers, and of the remaining conformers, 7 possessed a helix C-terminally extended by 1–4 residues. The second α-helix extends from residues 25–30 in 9 of the 20 conformers, 5 conformers display helices C-terminally extended by 1–2 residues, and the remaining ones present less regular helical fragments for residues 25–38. Among the low-energy conformers one is found with an α-helix encompassing residues 11–33, but generally the region 23–27 is poorly defined. Hydrogen bonds between carbonyl oxygen atoms of residue i and amide hydrogen atoms of residue i + 4 are observed in more than 50% of the cases in the segments 10–22 and 25–36. Considering that residues 23–27 exhibited only weak crosspeaks in the [15N,1H]-HSQC spectrum and that only a few correlations in the corresponding 3D NOESY spectrum were detected, we suspect that this region undergoes slow conformational exchange corresponding to a kink motion of the two helices with respect to each other (vide infra).

FIGURE 6.

Presentation of the peptide backbone of the 20 lowest energy calculated conformers of E3-TM7-T40 in DPC micelles. Backbone atoms of residues 10–22 (A) and 26–31 (B) have been used to superimpose the structures, and the corresponding bonds are coded in black. Panels C and D display individual conformers with different dihedrals in the segment comprising Leu-23-Pro-24-Leu-25.

The helical nature of residues 10–20 computed from NOEs are supported by lowered values of the scalar coupling constants 3JHNα in this segment of EL3-TM7-CT40 (Fig. 5), and a few couplings below 6 Hz are additionally observed in the segment 27–33. In contrast to the putative TM7 region of the peptide, no elements of regular secondary structure were observed within the carboxy-terminal (CT) part throughout all conformers, but two conformers possessed backbone dihedral angles corresponding to an α-helix for residues 46–48, one conformer exhibited such dihedral angles for residues 55–57, and one for residues 60–62. We additionally noticed significantly lowered values for the 3JHNα coupling constants for most residues in the segment comprising residues 44–60. However, we have only observed a few α,N (i, i + 2) NOEs and only a single α,β (i, i + 3) NOE. The fact that NOEs between sequential amide protons are measured throughout this part of EL3-TM7-CT40 but only a few medium-range NOEs could be detected indicates the presence of transient helical conformations with considerable residual flexibility. Considering that also the values for the 15N{1H}-NOE are reduced to ∼0.4–0.55 in that segment (vide infra), we conclude that strong preference for helical conformations exists in that part but that the persistence of helix conformations is low, similar to what has been referred to in the literature as a nascent helix (47). We suspect that the structure in the cytosolic segment is controlled by partitioning of residues into the water-micelle interface (vide infra). When superimposing residues 33–73 the RMSD of the backbone atoms is 9.87 ± 2.61 Å, indicating high flexibility of this part of the molecule.

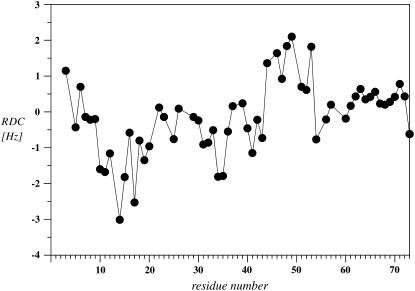

To further characterize to which extent parts of the polypeptide chain are structured, we have measured RDCs in stretched polyacrylamide gels. The data are depicted in Fig. 7 and reveal that the RDCs are comparably small, indicating that scaling due to motion occurs. Two segments with increased absolute values (>1 Hz) are observed between residues 10 and 20 and between residues 44 and 53. In other regions the values are below 1 Hz, indicating extensive motional averaging.

FIGURE 7.

RDCs of E3-TM7-T40 measured at 700-MHz proton frequency.

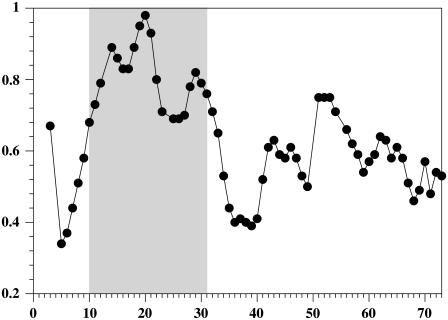

To further investigate to which extent amide protons were protected from solvent exchange, we measured reductions in amide proton intensities due to saturation transfer in an [15N,1H]-HSQC spectrum where the water line was saturated by low-power irradiation during the relaxation delay. Markedly reduced saturation transfer (>70% remaining peak intensity) was observed in the segment 10–30, and rapid exchange was found at the termini of the peptide as well as in the region Asn-34 to Thr-41 (Fig. 8). Reduced 3JHNα and amide proton exchange rates are also observed for residues 44–61, supporting the view that this segment is partially structured.

FIGURE 8.

Relative peak volumes of signals computed from HSQC spectra recorded in the presence of low-power presaturation on the water resonance during the relaxation delay relative to a reference experiment without presaturation. In this figure and in Figs. 10 and 11, the putative TM region is shaded.

Dynamics of TM7 as derived from 15N relaxation

It has been generally recognized that less well-defined regions of protein structures computed from NMR solution data may be due to either the intrinsic flexibility of the backbone in that particular segment or to an insufficient number of resolved and assigned NOEs, thereby preventing convergence of structure calculations toward a particular conformation. The determination of internal backbone dynamics, in principle, can be used to distinguish the two cases. In particular, values of the 15N{1H}-NOE allow discrimination between well-structured regions of the protein chain from those that display flexibility.

The values of the heteronuclear NOE are depicted in Fig. 9. High values (>0.6) are usually observed in elements of secondary structure as well as in rather rigid short loops. In TM7 only the segment encompassing residues Val-10 to Trp-29 fall into this category. The values around Pro-24 in this segment are significantly reduced. A second region of relatively high NOE (>0.5) values can be found in the segment comprising the putative cytosolic residues Asp-51 to Ser-59. From residue Gln-62 to the C-terminus of the peptide the values of the NOE steadily decrease and adopt (large) negative values toward the termini, indicating that the last 10 residues of CT freely diffuse in solution. Residues preceding the putative transmembrane helix (Asp-9–Ser-1) also exhibit increasingly low values. Thus, based on heteronuclear NOEs both termini are rather flexible.

FIGURE 9.

Values of the 15N{1H}-NOE recorded at 700-MHz proton frequency.

Orientation and membrane integration topology

Tools from bioinformatics, such as secondary structure prediction, based on position-specific scoring matrices (48,49) predicted the segments Asp-9 to Ser-22 and Pro-24 to Ala-32 to be helical (see Supplementary Material) with high confidence. The analysis of the hydrophobicity profiles concluded that the segment Val-10 to Ala-33 forms the seventh transmembrane helix in intact Ste2p, but it is unclear whether this segment would adopt such a topology in the truncated version of this GPCR investigated here in the context of a detergent micelle. Previous fluorescence measurements on the synthetic 64-residue analog of EL3-TM7-CT40 in the presence of dimyristoylphosphocholine/dimyristoylphosphoglycerol vesicles showed that the single Trp in TM7 was in a hydrophobic environment (18). To probe the micelle-integration topology of EL3-TM7-CT40, we determined the effects from paramagnetic relaxation due to the presence of micelle-integrating spin labels. In this and previous studies we used 5- and 16-doxylstearate, which are presumed to probe the vicinity of the phospholipid headgroups or the membrane interior, respectively. We note that the position of the methyl group at the end of a detergent's aliphatic chain is poorly defined. In contradiction to many pictures found in textbooks, a radial extension of the lipid chains from the center of the micelle would result in uneven distributions of atoms across the micelle and, in particular, higher atom density in the center. To account for this fact a statistical model has been proposed by Dill and Flory (50) wherein the termini of the lipid chain partially bend back toward the micelle surface, a behavior that has been verified from MD calculations performed on solvated DPC or SDS micelles. This observation complicates the interpretation of spin label results with 16-doxylstearate, and indeed we observe signal attenuations corresponding to the amide moieties thought to be located at the interface as well as the interior of the micelle.

The data derived from the two spin labels are depicted in Fig. 10. For a rigid straight helix traversing the micelle, attenuations due to 16-doxylstearate are expected to be strongest for residues located in the center of the micelle (Fig. 10 B), with moderate attenuations for residues at the interface, whereas the effects due to 5-doxylstearate should be largely limited to residues located at the interface (Fig. 10 A). Signal attenuations for residues 64–73 are small and indicate that the C-terminal segment does not interact with the micelle surface. In the following we will consider all residues with attenuations larger than 50% as significantly attenuated. The data reveal such attenuations in the presence of 5-doxylstearate for residues 9–11 with the maximum at Val-10 and for residues 28–30 with the maximum around residue Trp-29. A broader third segment with strong attenuations occurs between residues 18–23 with maximum attenuations around residue Ser-22.

FIGURE 10.

Relative HSQC signal intensities measured on EL3-TM7-CT40 in the presence of various spin labels: 5-doxylstearate (A), 16-doxylstearate (B), and Gd-DOTA (C). The chemical structures of the spin labels are indicated in D.

For 16-doxylstearate strong attenuations are observed for residues 18–23 with signals reduced to <20% of their original intensity. In addition, we observed much less reduced signals in the segment Leu-25–Ser-26, indicating that it is not primarily located in the center of the micelle. Furthermore, there is strong evidence for a second site of interaction with the micelle. Both 5-doxylstearate as well as 16-doxylstearate data indicate very strong attenuations for the segment comprising residues 52–57 centered around residue Phe-53. The view that these two sites are making contacts with the micelle surface is supported by reduced amide protons exchange (vide supra). Reductions due to the spin labels—although to a much smaller extent—also occur for residues Ile-42–Thr-43 and around residue Thr-47. To better distinguish attenuation from micelle surface attached moieties from those buried in the micelle interior, we have additionally performed experiments with the soluble spin label Gd-DOTA (51). In this case the spin label is distributed in solution and should therefore probe for solvent-exposed amide moieties. The data reveal that amide protons in the segment comprising residues 9–29 are largely protected from solvent access and also confirm the presence of the second site of solvent protection in the C-terminal part of the polypeptide chain around residue Phe-53.

DISCUSSION

Studies of membrane proteins remain a major challenge in structural biology. Although knowledge on β-barrel membrane proteins is increasing steadily, our understanding of structural aspects of helical membrane proteins is still poor. In a remarkable pioneering effort Sanders et al. have recently incorporated the full-length vasopressin GPCR into DPC micelles (52,53). However, their TROSY spectra display only 80 of the original 250 peaks, indicating strongly reduced T2 relaxation times for most residues of the GPCR. The authors have proposed that signals from the TM parts most likely are missing. Opella et al. (54) have presented data on full-length CXCR1 in aligned bicelles from solid-state NMR experiments demonstrating that the receptor was integrated into the bicelles. Despite these promising results with intact GPCRs, direct analysis of these molecules is at present confounded by the immense problems associated with producing full-length, biologically active receptors, purifying and reconstituting these molecules, and measuring high quality NMR spectra in membranes. A number of researchers have looked at fragments of GPCRs as surrogates to obtain biophysical data relevant to the intact protein.

Pervushin et al. studied peptides derived from the N-terminus of bacteriorhodopsin comprising residues 1–71 in organic solvent mixtures consisting of chloroform and methanol and in SDS micelles (55). Yeagle and co-workers have synthesized peptides corresponding to the cytosolic loops and TMDs of rhodopsin and bacteriorhodopsin and studied them by NMR, proposing that the structures of these fragments resemble the corresponding regions in the native receptors (13,56–58). Pellegrini and co-workers examined a 27-amino acid peptide derived from the third cytosolic loop of the PTH1 receptor in both the linear form and when cyclized with an octamethylene linker designed to maintain the proposed distance of 12 Å for the loop-anchoring points (59). Pellegrini and Mierke additionally studied the extracellular domain of the PTH1 receptor in the presence of DPC micelles (60). Recently, excellent progress has been made in expressing and isotopically labeling regions of the CB2 receptor containing loops and up to two TMs of this GPCR, but a high resolution structure of these 54-residue and 74-residue peptides is not yet available (61,62).

In previous investigations on EL3-TM7-CT40 of Ste2p, TFE/water (1:1) and chloroform/methanol/water (4:4:1) (20) were used to mimic the membrane environment. Although the properties of interfacial or core regions of the membrane can be imitated by such solvent mixtures, phospholipid micelles are better mimics of biological membranes because they possess a completely nonpolar interior and a steep gradient of charge density at the water interface similar to that of a bilayer and allow the N-terminus and CT of the receptor to be exposed to an aqueous environment. Both micelles (63) and the recently introduced minibicelles (64) have found widespread use in solution NMR studies of peripheral as well as integral membrane peptides/proteins. The Garvin (65) and Sanders (66) laboratories have recently compared detergents for NMR studies of membrane proteins. DPC has been extensively used to study membrane proteins and peptides (55) and taking into account solubilization, stabilization, and functional reconstitution of integral membrane proteins, 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-[phospho-rac-(1-glycerol)] (LPPG) was concluded to be a detergent of choice for measurement of NMR spectra (54). We measured [15N,1H]-HSQC spectra of EL3-TM7-CT40 in various membrane-mimicking environments including SDS, DPC, DHPC (1,2-dihexanoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine), and LPPG and observed the best sample stability and good spectral quality in DPC solution.

This study aimed at elucidating the structure of a fragment from the yeast GPCR Step2p, including the seventh TM domain, the EL3 loop, and 40 residues from the CT tail in DPC micelles. Based on the structural information, dynamics, and spin label data we propose the following picture for integration of the peptide into the micelle: The segment encompassing residues Val-10 to Ala-30 forms a helix that integrates into the interior of the micelle. This α-helix is disrupted around Pro-24, and considerable flexibility exists such that the orientations of the N- and C-terminal parts of the α-helix are not well defined with respect to each other.

The hydrophobic core region of biologically relevant membranes was characterized from x-ray and neutron diffraction data on a dioleoylphosphocholine bilayer (67) and is ∼25–30 Å in thickness, with the distance between phosphorous atoms adopting values of ∼40 Å. In addition, a very steep gradient of charge density exists in the shell located between 10 and 30 Å from the bilayer center. The distance of the phosphorous atoms from the micelle center as extracted from trajectories of MD calculations performed on a 54-lipid DPC micelle aggregate is ∼17 Å (68), compared to 20 Å in the bilayer (67). Given this considerable mismatch in hydrophobic thickness of DPC and a bilayer, it is reasonable to assume that either the lipid or peptide would adapt structurally to minimize unfavorable hydrophobic interactions between nonpolar peptide residues and the aqueous buffer.

In the case of the rigidly structured β-barrel outer membrane protein of E. coli, Wüthrich and co-workers could demonstrate that it is the lipids that rearrange such that the hydrophobic part of OmpX is completely covered (69), and data based upon MD calculations of a detergent-OmpX complex suggested a prolate shape of the mixed micelle (70). In contrast the helical hydrophobic stretch of EL3-TM7-CT40 is much less rigid and more easily adaptable to the micelle requirements. Our data demonstrate that in the case of EL3-TM7-CT40, bending of the helix helps to accommodate all hydrophobic residues in the 10–30 region of EL3-TM7-CT40 in the interior of the micelle. The situation is schematically sketched in Fig. 11. The positions of the spin labels 16- and 5-doxylstearate are depicted as shaded areas in the center and the outer shell of the micelle, respectively. A straight helix, in principle, should be recognized by the fact that signal attenuations due to the presence of the different spin labels are located in different areas of the peptide segment, i.e., the effects due to 5-doxylstearate would be larger toward the termini (Fig. 11 A) and the effects due to 16-doxylstearate are expected to be most pronounced in the center of the helix (Fig. 11 C). In the case of the bent helix, larger parts of the polypeptide segment would actually be located in regions in which enhanced paramagnetic relaxation due to the presence of 5-doxylstearate occurs (compare Fig. 11, A and B).

FIGURE 11.

Possible insertion modes of the TM portion of the peptide into the DPC micelle. The areas of largest influence for the two spin labels 5-doxylstearate (top, A and B) and 16-doxylstearate (bottom, C and D) have been shaded. Below the micelles expected residual signal intensities for the various insertion topologies are depicted. In the center, the experimental signal attenuations are shown for a segment containing the putative TM segment (see text).

In the absence of motion around the helix kink, few attenuations for residues in the central segment of the helix due to the 5-doxylstearate spin label are expected, whereas substantial reductions in the intensities of these residues are expected to occur in the presence of 16-doxylstearate. Motion around the helix kink would be expected to average out differences between the data from the two different spin labels in the central segment of the helix. Moreover, the presence of the polar Ser-22, Ser-26, and Ser-27 residues in proximity to the Pro 24 kink may help to transfer this part of the peptide out of the center of the micelle into the aqueous compartment (notice the reduced attenuation of residues 25–27 from both 5-doxylstearate and 16-doxylstearate in Fig. 10, A and B, respectively). Movement of this part of the peptide to the surface of the micelle would also explain why signal attenuations from the 16-doxylstearate spin label are weaker for residues after Ser-26 compared to those in the Val-10 to Ser-22 segment. We conclude that a significant number of residues from the TM7 helix are integrated into DPC, but considerable motion exists about Pro-24. The view presented above is supported by the RDC data. It must be emphasized that the magnitude of the RDCs depends on the orientation of the corresponding NH bond vectors relative to the alignment frame, and it is therefore not directly related to how rigidly a certain segment is folded. However, values larger than 1 Hz are incompatible with extensive motional averaging, and hence the data clearly indicate that the N-terminal part of the TM helix is more rigid than the C-terminal part. The lack of significant RDCs, the reduced values of the heteronuclear-NOE around the Pro-24 site, and the reduced effects from the spin labels in the segment 25–30 strongly suggest that the C-terminal part of the TM helix is not uniquely oriented relative to the N-terminal domain.

The TM helix revealed by the NMR analysis of EL3-TM7-CT40 in DPC is consistent with predictions from bioinformatics (vide supra). Surprisingly, the spin label data depicted in Fig. 10 also clearly exposed the presence of a second site of strong interaction with the micelle involving residues centered around Phe-53. Both aromatic residues display favorable interaction energies with the micelle-water interface (vide infra). The 16-doxylstearate and the Gd-DOTA data (Fig. 10, B and C) as well as the amide proton exchange data indicate that the two sites of interactions with the micelle—the helical region encompassing residues 10–30 and the C-terminal region around residue Phe-53—integrate differently in the micelle. In particular, the DOTA and the 16-doxylstearate data indicate that the helical segment is buried in the micelle interior over an extended region, whereas interactions with residues Phe-53–Tyr-54 are limited to a much shorter region and hence can hardly be explained by a large micelle-buried segment. Based on the presence of reduced scalar couplings and the occurrence of NOEs between sequential amide protons, we propose that in contrast to the micelle-embedded TM7 the C-terminal part around residue Phe-53 is more compatible with the presence of a short surface-associated segment, with a strong preference for helical conformations, which are tightly anchored onto the micelle. Interestingly, the RDCs in this segment have opposite sign to those from the TM helix and therefore indicate that the orientation of the nascent helix in that part is very different from the TM helix. In that respect the RDCs support the view that the cytosolic portion contains a nascent helix, which is surface associated rather than integrated.

The NMR data that were used for the structure calculation contain few long-range restraints, and hence the tertiary structure of the polypeptide seems to be poorly defined. However, the lack of long-range NOEs, reduced RDCs, and H-NOEs as well as the effects of spin labels on different regions of EL3-TM7-CT40 indicate that the lack of tertiary structure is not primarily due to an insufficient number of restraints during the structure calculation. Rather, it likely reflects the flexible nature of this protein, both in the TM helix as well as in the cytosolic part. Recently, the structural role of Pro in TM helices has been systematically investigated and Pro residues were found to induce kink motion about the Pro position, thereby decoupling the motions of the segment before and after the Pro residues (71).

The topology of membrane association/insertion was recently successfully predicted using an experimental thermodynamic parameter for transferring whole amino acids from bulk water into the membrane interface or into the membrane interior as determined by Wimley and White (72,73). Their data have recently been verified in a biological system using a clever readout system (74). We have seen that these data reliably predict the orientation of membrane-associated peptides from the NPY family (75). In Fig. 12 values for transfer into the interior (left) or interface (right) are plotted along the sequence. The segment presenting the transmembrane helix including residues 10–30 is immediately recognized because no residues with strongly unfavorable energies for partitioning into the membrane interior are found in that stretch. Moreover, the amphiphilic nature of the C-terminal half of the peptide is obvious with highly hydrophilic residues such as Asp (ΔGoct 3.64 kcal/mol; ΔGwif 1.23 kcal/mol) frequently occurring in the vicinity of hydrophobic residues like Phe (ΔGoct −1.71 kcal/mol; ΔGwif −1.13 kcal/mol). The importance of aromatic residues, in particular of Tyr and Trp, for anchoring polypeptide stretches at the interface has been widely recognized; in fact these residues are highly enriched in interfacial regions (aromatic belt). No such residues are found in the TM region except for Trp-29, which likely helps to anchor one end of the TM helix to the interface. In contrast, four aromatic residues are located in the stretch Phe-46–Phe-61. We note that the values for the 15N{1H}-NOE are slightly increased for residues 50–60, and these same residues also show more intense NHi to NHi+1 NOEs. We suspect that the stabilization of secondary structure in this region is largely due to anchoring of this region of the peptide chain on the micelle surface. In contrast to the aromatic-containing central region of CT40, the C-terminal decapeptide stretch after residue 60 lacks any aromatic residues which could possibly serve as membrane anchors and displays quite small 5-doxylstearate attenuations and is fully flexible based on dynamics data and the absence of medium- or long-range NOEs.

FIGURE 12.

Plot of the free energies for transferring whole amino acids as determined by Wimley and White into the membrane interior (left) and the membrane-water interface (right) for the sequence of the investigated peptide (72,73). The area of favorable energies is shaded.

A systematic analysis of peptide fragments in different solvents and detergents should provide experimental evidence for the specific role played by these media in determining the structure of the polypeptide. Our work on the structure of EL3-TM7-CT40 in DPC micelles points to both similarities and certain differences in comparison to the organic solvent mixtures. In DPC micelles and organic-aqueous solvents, this peptide exhibits a helix encompassing residues 10–30 with a kink around Pro-24 that results in significant flexibility in both cases. Moreover, certain helical tendencies are revealed for residues in the 43–58 range of the peptide both in DPC micelles and organic-aqueous solvents. However, the C-terminus after residue 62 is clearly unstructured in DPC micelles, whereas the C-terminal helix in the TFE/water (1:1) extends up to residue 70. Moreover, whereas the segment 34–41 in TFE/water is part of the second helix, it is unstructured in DPC, a conclusion that is supported by the lack of medium range (i, i + 3) NOEs as well as NOEs involving sequential amide protons, low values of the 15N{1H}-NOE, and little protection from amide proton exchange. In the isotropic environment of an organic-aqueous solvent, structuring effects due to the steep gradient in hydrophobicity in the micelles are absent, which might explain why the cytosolic tail of EL3-TM7-CT40 behaves somewhat differently in organic-aqueous mixtures and in DPC micelles. Thus, it seems that DPC micelles may be a better environment for learning about conformational preferences of the extra- and intracellular domains of polytopic molecules.

Taking into account the enormous problems associated with the expression, purification, and reconstitution of intact GPCRs into membrane-mimetic environments suitable for biophysical studies, investigations on fragments of these proteins seem to be well justified. As the size of these fragments increases to include more than one helix, our understanding of the involvement of helix-helix interactions in influencing the secondary and tertiary structure of individual TM helices will improve. Although many synthetic problems may be reduced when using fragments of GPCRs, a crucial question remains whether these truncated constructs are able to successfully mimic structural features of the much longer polypeptides. Many groups have demonstrated that smaller fragments of soluble, well-structured proteins display increased propensity to transiently adopt conformations similar to those encountered for that particular stretch when placed in the context of the full polypeptide (for example, see Dyson et al. (47)). However, these studies have usually also revealed that the fragments are still fairly flexible. This is by no means surprising, considering that many crucial and stabilizing medium- or long-range interactions are missing. Moreover, solvent access is not restricted for soluble fragments, and therefore solvation competes with intramolecular hydrogen bonding. Solvation is much less favorable when the polypeptide is partitioned into a membrane (76). Indeed, many peptides, which are unfolded in water, adopt secondary structure when placed into a membrane-mimicking environment, known as the coupled partitioning folding (77). Furthermore, many relatively short peptides fold into stable helices in micelles, both in transmembrane (e.g., 76,78,79) or surface-associated fashion (e.g., 80–82).

Our study has demonstrated that a 73-residue polypeptide comprising the entire seventh TM of Ste2p does adopt a helical conformation even when Pro is part of the helix-spanning stretch. The study, however, has also demonstrated that the helix is significantly destabilized around Pro-24 and that the orientation is presumably not such that the helix is predominantly straight but rather undergoes larger kink motions. It is possible that such motions are completely or partially suppressed in the presence of the other transmembrane helices of Ste2p, some of which pack against the seventh helix. However, the kink in the structure would be expected to confer residual conformational flexibility that may be very important during signal transduction through Ste2p. The study also indicates that most of the residues in the predicted TM helix have been selected for favorable partitioning into the corresponding membrane compartment and a few have been selected to form crucial helix-helix interactions. We suspect that Ser-22 and Ser-26 are involved in forming such interactions, because in the absence of other TM segments they tend to promote partitioning of that part of TM7 into the vicinity of the micellar interface. Finally, even in the context of a DPC micelle, regions of the CT tail have some propensity to assume transient helical structures. Similar to what we found for the CT of Ste2p, the crystal structure of rhodopsin revealed that the cytoplasmic extension proximal to TM7 contained a helical segment called H8 (4). Model peptides corresponding to H8 were studied under a variety of conditions with the conclusion that H8 acts as a membrane-surface recognition domain, where amino acid side chains can interact with phospholipid headgroups (83). The participation of these “helical” domains in protein-protein interactions with regulatory elements of the signal transduction system remains to be demonstrated.

CONCLUSIONS

This study has demonstrated that polypeptides corresponding to fragments of GPCRs can be incorporated into phospholipid micelles, provided that certain protocols for incorporation are followed and that detailed information concerning the structure of the peptide and the topology of various regions in the micelle can be deduced. The work revealed details of the folding of a fragment from the yeast Ste2p receptor and demonstrated that certain structural and/or dynamical features of such a fragment are different in organic solvents and in the presence of DPC micelles. Many features in the latter environment can be explained by anisotropic properties present in micelles and membranes but not in organic-aqueous solvents. The study also demonstrated that even in DPC micelles the isolated seventh TM helix is not rigid and that this flexibility, although possibly reduced in the context of TM-TM contacts that exist in the receptor, may be an important aspect of the conformational change that is triggered by binding of α-factor to Ste2p. Future studies will be devoted to developing systems that allow study of helix-helix interactions. This work provides an important starting point for such investigations.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We express our thanks to Fred Damberger, Thorsten Hermann, and Peter Güntert for instructions for using the programs CARA, ATNOS/CANDID, and CYANA.

This work was supported by grants GM 22086 and GM 22087 from the National Institutes of Health.

Editor: Mark Girvin.

References

- 1.Mombaerts, P. 1999. Seven-transmembrane proteins as odorant and chemosensory receptors. Science. 286:707–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lundstrom, K. 2005. The future of G protein-coupled receptors as targets in drug discovery. IDrugs. 8:909–913. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thompson, M. D., W. M. Burnham, and D. E. Cole. 2005. The G protein-coupled receptors: pharmacogenetics and disease. Crit. Rev. Clin. Lab. Sci. 42:311–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Palczewski, K., T. Kumasaka, T. Hori, C. A. Behnke, H. Motoshima, B. A. Fox, I. Le Trong, D. C. Teller, T. Okada, R. E. Stenkamp, M. Yamamoto, and M. Miyano. 2000. Crystal structure of rhodopsin: a G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 289:739–745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Flower, D. R. 1999. Modelling G-protein-coupled receptors for drug design. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1422:207–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Strader, C. D., T. M. Fong, M. R. Tota, D. Underwood, and R. A. Dixon. 1994. Structure and function of G protein-coupled receptors. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 63:101–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ballesteros, J. A., L. Shi, and J. A. Javitch. 2001. Structural mimicry in G protein-coupled receptors: implications of the high-resolution structure of rhodopsin for structure-function analysis of rhodopsin-like receptors. Mol. Pharmacol. 60:1–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ji, T. H., M. Grossmann, and I. Ji. 1998. G protein-coupled receptors. I. Diversity of receptor-ligand interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 273:17299–17302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grisshammer, R., J. F. White, L. B. Trinh, and J. Shiloach. 2005. Large-scale expression and purification of a G-protein-coupled receptor for structure determination—an overview. J. Struct. Funct. Genomics. 6:159–163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sarramegna, V., I. Muller, A. Milon, and F. Talmont. 2006. Recombinant G protein-coupled receptors from expression to renaturation: a challenge towards structure. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 63:1149–1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sarramegna, V., F. Talmont, P. Demange, and A. Milon. 2003. Heterologous expression of G-protein-coupled receptors: comparison of expression systems from the standpoint of large-scale production and purification. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 60:1529–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Katragadda, M., J. L. Alderfer, and P. L. Yeagle. 2001. Assembly of a polytopic membrane protein structure from the solution structures of overlapping peptide fragments of bacteriorhodopsin. Biophys. J. 81:1029–1036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yeagle, P. L., and A. D. Albert. 2002. Use of nuclear magnetic resonance to study the three-dimensional structure of rhodopsin. Methods Enzymol. 343:223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Xie, H., F. X. Ding, D. Schreiber, G. Eng, S. F. Liu, B. Arshava, E. Arevalo, J. M. Becker, and F. Naider. 2000. Synthesis and biophysical analysis of transmembrane domains of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae G protein-coupled receptor. Biochemistry. 39:15462–15474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Valentine, K. G., S. F. Liu, F. M. Marassi, G. Veglia, S. J. Opella, F. X. Ding, S. H. Wang, B. Arshava, J. M. Becker, and F. Naider. 2001. Structure and topology of a peptide segment of the 6th transmembrane domain of the Saccharomyces cerevisae alpha-factor receptor in phospholipid bilayers. Biopolymers. 59:243–256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arshava, B., I. Taran, H. Xie, J. M. Becker, and F. Naider. 2002. High resolution NMR analysis of the seven transmembrane domains of a heptahelical receptor in organic-aqueous medium. Biopolymers. 64:161–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Naider, F., B. Arshava, F. X. Ding, E. Arevalo, and J. M. Becker. 2001. Peptide fragments as models to study the structure of a G-protein coupled receptor: the alpha-factor receptor of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biopolymers. 60:334–350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naider, F., F. X. Ding, N. C. VerBerkmoes, B. Arshava, and J. M. Becker. 2003. Synthesis and biophysical characterization of a multidomain peptide from a Saccharomyces cerevisiae G protein-coupled receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52537–52545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naider, F., S. Khare, B. Arshava, B. Severino, J. Russo, and J. M. Becker. 2005. Synthetic peptides as probes for conformational preferences of domains of membrane receptors. Biopolymers. 80:199–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Estephan, R., J. Englander, B. Arshava, K. L. Samples, J. M. Becker, and F. Naider. 2005. Biosynthesis and NMR analysis of a 73-residue domain of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae G protein-coupled receptor. Biochemistry. 44:11795–11810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Naider, F., and J. M. Becker. 2004. The alpha-factor mating pheromone of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: a model for studying the interaction of peptide hormones and G protein-coupled receptors. Peptides. 25:1441–1463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, Q., and J. B. Konopka. 1996. Regulation of the G-protein-coupled alpha-factor pheromone receptor by phosphorylation. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:247–257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Melnyk, R. A., A. W. Partridge, J. Yip, Y. Wu, N. K. Goto, and C. M. Deber. 2003. Polar residue tagging of transmembrane peptides. Biopolymers. 71:675–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Englander, J., L. Cohen, B. Arshava, R. Estephan, J. M. Becker, and F. Naider. 2006. Selective labeling of a membrane peptide with (15)N-amino acids using cells grown in rich medium. Biopolymers. 84:508–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tjandra, N., and A. Bax. 1997. Direct measurement of distances and angles in biomolecules by NMR in a dilute liquid crystalline medium. Science. 278:1111–1114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sass, H. J., G. Musco, S. J. Stahl, P. T. Wingfield, and S. Grzesiek. 2000. Solution NMR of proteins within polyacrylamide gels: diffusional properties and residual alignment by mechanical stress or embedding of oriented purple membranes. J. Biomol. NMR. 18:303–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clore, G. M., and A. M. Gronenborn. 1991. Applications of three- and four-dimensional heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy to protein structure determination. Prog. Nucl. Magn. Reson. Spectrosc. 23:43–92. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fesik, S. W., and E. R. P. Zuiderweg. 1990. Heteronuclear three-dimensional NMR spectroscopy of isotopically labelled biological macromolecules. Q. Rev. Biophys. 23:97–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Grzesiek, S., and A. Bax. 1992. Correlating backbone amide and side chain resonances in larger proteins by multiple relayed triple resonance NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:6291–6293. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wittekind, M., and L. Mueller. 1993. HNCACB, a high-sensitivity 3D NMR experiment to correlate amide-proton and nitrogen resonances with the alpha-carbon and beta-carbon resonances in proteins. J. Magn. Reson. Ser. B. 101:201–205. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Montelione, G. T. 1992. An efficient triple-resonance experiment using 13C isotropic mixing for determining sequence-specific assignments of isotopically enriched proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:10974–10975. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bax, A., G. M. Clore, and A. M. Gronenborn. 1990. 1H-1H correlation via isotropic mixing of 13C magnetization, a new three-dimensional approach for assigning 1H and 13C spectra of 13C enriched proteins. J. Magn. Reson. 88:425–431. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Olejniczak, E. T., R. X. Xu, and S. W. Fesik. 1992. A 4D HCCH-TOCSY experiment for assigning the side chain 1H and 13C resonances of proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 2:655–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamazaki, T., J. D. Forman Kay, and L. E. Kay. 1993. 2-dimensional NMR experiments for correlating C-13-beta and H-1-delta/epsilon chemical-shifts of aromatic residues in C-13-labeled proteins via scalar couplings. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115:11054–11055. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zerbe, O., T. Szyperski, M. Ottiger, and K. Wüthrich. 1996. Three-dimensional H-1-TOCSY-relayed ct-[C-13,H-1]-HMQC for aromatic spin system identification in uniformly C-13-labeled proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 7:99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavanagh, J., W. J. Fairbrother, A. G. Palmer, and N. J. Skelton. 1996. Protein NMR Spectroscopy: Principles and Practice. Academic Press, San Diego, CA.

- 37.Noggle, J. H., and R. E. Schirmer. 1971. The Nuclear Overhauser Effect—Chemical Applications. Academic Press, New York.

- 38.Szyperski, T., P. Güntert, G. Otting, and K. Wüthrich. 1992. Determination of scalar coupling constants by inverse Fourier transformation of in-phase multiplets. J. Magn. Reson. 99:552–560. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bartels, C., T.-h. Xia, M. Billeter, P. Güntert, and K. Wüthrich. 1995. The program XEASY for computer-supported spectral analysis of biological macromolecules. J. Biomol. NMR. 6:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keller, R. L. J. 2004. The Computer Aided Resonance Assignment Tutorial. Cantina Verlag, Goldau, Switzerland.

- 41.Cornilescu, G., F. Delaglio, and A. Bax. 1999. Protein backbone angle restraints from searching a database for chemical shift and sequence homology. J. Biomol. NMR. 13:289–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Güntert, P., C. Mumenthaler, and K. Wüthrich. 1997. Torsion angle dynamics for NMR structure calculation with the new program DYANA. J. Mol. Biol. 273:283–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Güntert, P. 2004. Automated NMR structure calculation with CYANA. Methods Mol. Biol. 278:353–378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Koradi, R., M. Billeter, and K. Wüthrich. 1996. MOLMOL—a program for display and analysis of macromolecular structures. J. Mol. Graph. 14:51–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Killian, J. A., T. P. Trouard, D. V. Greathouse, V. Chupin, and G. Lindblom. 1994. A general method for the preparation of mixed micelles of hydrophobic peptides and sodium dodecyl sulphate. FEBS Lett. 348:161–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kabsch, W., and C. Sander. 1983. Dictionary of protein secondary structure: pattern recognition of hydrogen-bonded and geometrical features. Biopolymers. 22:2577–2637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dyson, H. J., M. Rance, R. A. Houghton, R. A. Lerner, and P. E. Wright. 1988. Folding of immunogenic peptide fragments of proteins in water solution. J. Mol. Biol. 201:161–200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bryson, K., L. J. McGuffin, R. L. Marsden, J. J. Ward, J. S. Sodhi, and D. T. Jones. 2005. Protein structure prediction servers at University College London. Nucleic Acids Res. 33:W36–W38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones, D. T. 1999. Protein secondary structure prediction based on position-specific scoring matrices. J. Mol. Biol. 292:195–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dill, K. A., and P. J. Flory. 1981. Molecular organization in micelles and vesicles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 78:676–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hilty, C., G. Wider, C. Fernandez, and K. Wüthrich. 2004. Membrane protein-lipid interactions in mixed micelles studied by NMR spectroscopy with the use of paramagnetic reagents. ChemBioChem. 5:467–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tian, C., R. M. Breyer, H. J. Kim, M. D. Karra, D. B. Friedman, A. Karpay, and C. R. Sanders. 2006. Solution NMR spectroscopy of the human vasopressin v2 receptor, a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:5300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tian, C., R. M. Breyer, H. J. Kim, M. D. Karra, D. B. Friedman, A. Karpay, and C. R. Sanders. 2005. Solution NMR spectroscopy of the human vasopressin V2 receptor, a G protein-coupled receptor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127:8010–8011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park, S. H., S. Prytulla, A. A. De Angelis, J. M. Brown, H. Kiefer, and S. J. Opella. 2006. High-resolution NMR spectroscopy of a GPCR in aligned bicelles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128:7402–7403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pervushin, K. V., V. Orekhov, A. I. Popov, L. Musina, and A. S. Arseniev. 1994. Three-dimensional structure of (1–71)bacterioopsin solubilized in methanol/chloroform and SDS micelles determined by 15N–1H heteronuclear NMR spectroscopy. Eur. J. Biochem. 219:571–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yeagle, P. L., J. L. Alderfer, A. C. Salloum, L. Ali, and A. D. Albert. 1997. The first and second cytoplasmic loops of the G-protein receptor, rhodopsin, independently form beta-turns. Biochemistry. 36:3864–3869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yeagle, P. L., J. L. Alderfer, and A. D. Albert. 1997. Three-dimensional structure of the cytoplasmic face of the G protein receptor rhodopsin. Biochemistry. 36:9649–9654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yeagle, P. L., G. Choi, and A. D. Albert. 2001. Studies on the structure of the G-protein-coupled receptor rhodopsin including the putative G-protein binding site in unactivated and activated forms. Biochemistry. 40:11932–11937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Pellegrini, M., M. Royo, M. Chorev, and D. F. Mierke. 1996. Conformational characterization of a peptide mimetic of the third cytoplasmic loop of the G-protein coupled parathyroid hormone/parathyroid hormone related protein receptor. Biopolymers. 40:653–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pellegrini, M., and D. F. Mierke. 1999. Structural characterization of peptide hormone/receptor interactions by NMR spectroscopy. Biopolymers. 51:208–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zheng, H., J. Zhao, W. Sheng, and X. Q. Xie. 2006. A transmembrane helix-bundle from G-protein coupled receptor CB2: biosynthesis, purification, and NMR characterization. Biopolymers. 83:46–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhao, J., H. Zheng, and X.-Q. Xie. 2006. NMR characterization of recombinant transmembrane protein CB2 fragment CB2180–233. Protein Pept. Let. 13:335–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Damberg, P., J. Jarvet, and A. Gräslund. 2001. Micellar systems as solvents in peptide and protein structure determination. Methods Enzymol. 339:271–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vold, R. R., R. S. Prosser, and A. J. Deese. 1997. Isotropic solutions of phospholipid bicelles: a new membrane mimetic for high-resolution NMR studies of polypeptides. J. Biomol. NMR. 9:329–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Krueger-Koplin, R. D., P. L. Sorgen, S. T. Krueger-Koplin, I. O. Rivera-Torres, S. M. Cahill, D. B. Hicks, L. Grinius, T. A. Krulwich, and M. E. Girvin. 2004. An evaluation of detergents for NMR structural studies of membrane proteins. J. Biomol. NMR. 28:43–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sanders, C. R., A. K. Hoffmann, D. N. Grayn, M. H. Keyes, and C. D. Ellis. 2004. French swimwear for membrane proteins. ChemBioChem. 5:423–426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wiener, M. C., and S. H. White. 1992. Structure of a fluid dioleoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer determined by joint refinement of x-ray and neutron diffraction data. III. Complete structure. Biophys. J. 61:437–447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tieleman, D. P., D. van der Spoel, and H. J. C. Berendsen. 2000. Molecular dynamics simulation of dodecylphosphocholine micelles at different aggregate sizes: micellar structure and chain relaxation. J. Phys. Chem. 104:6380–6388. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fernandez, C., C. Hilty, G. Wider, and K. Wüthrich. 2002. Lipid-protein interactions in DHPC micelles containing the integral membrane protein OmpX investigated by NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:13533–13537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bockmann, R. A., and A. Caflisch. 2005. Spontaneous formation of detergent micelles around the outer membrane protein OmpX. Biophys. J. 88:3191–3204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bright, J. N., and M. S. P. Sansom. 2003. The flexing/twirling helix: exploring the flexibility about molecular hinges formed by proline and glycine motifs in transmembrane helices. J. Phys. Chem. 107:627–636. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wimley, W. C., and S. H. White. 1996. Experimentally determined hydrophobicity scale for proteins at membrane interfaces. Nat. Struct. Biol. 3:842–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.White, S. H., and W. C. Wimley. 1998. Hydrophobic interactions of peptides with membrane interfaces. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1376:339–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hessa, T., H. Kim, K. Bihlmaier, C. Lundin, J. Boekel, H. Andersson, I. Nilsson, S. H. White, and G. von Heijne. 2005. Recognition of transmembrane helices by the endoplasmic reticulum translocon. Nature. 433:377–381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bader, R., and O. Zerbe. 2005. Are hormones from the neuropeptide Y family recognized by their receptors from the membrane-bound state? ChemBioChem. 6:1520–1534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Popot, J. L., and D. M. Engelman. 2000. Helical membrane protein folding, stability, and evolution. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 69:881–922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.White, S. H., and W. C. Wimley. 1999. Membrane protein folding and stability: physical principles. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 28:319–365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.MacKenzie, K. R., J. H. Prestegard, and D. M. Engelman. 1997. A transmembrane helix dimer: structure and implications. Science. 276:131–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Papavoine, C. H., J. M. Aelen, R. N. Konings, C. W. Hilbers, and F. J. Van de Ven. 1995. NMR studies of the major coat protein of bacteriophage M13. Structural information of gVIIIp in dodecylphosphocholine micelles. Eur. J. Biochem. 232:490–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Brown, L. R., and K. Wüthrich. 1981. Melittin bound to dodecylphosphocholine micelles. H-NMR assignments and global conformational features. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 647:95–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ladokhin, A. S., and S. H. White. 1999. Folding of amphipathic alpha-helices on membranes: energetics of helix formation by melittin. J. Mol. Biol. 285:1363–1369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Bader, R., A. Bettio, A. G. Beck-Sickinger, and O. Zerbe. 2001. Structure and dynamics of micelle-bound neuropeptide Y: comparison with unligated NPY and implications for receptor selection. J. Mol. Biol. 305:307–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Krishna, A. G., S. T. Menon, T. J. Terry, and T. P. Sakmar. 2002. Evidence that helix 8 of rhodopsin acts as a membrane-dependent conformational switch. Biochemistry. 41:8298–8309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.