Abstract

Single-channel osmotic water permeability (pf) is a key quantity for investigating the transport capability of the water channel protein, aquaporin. However, the direct connection between the single scalar quantity pf and the channel structure remains unclear. In this study, based on molecular dynamics simulations, we propose a pf-matrix method, in which pf is decomposed into contributions from each local region of the channel. Diagonal elements of the pf matrix are equivalent to the local permeability at each region of the channel, and off-diagonal elements represent correlated motions of water molecules in different regions. Averaging both diagonal and off-diagonal elements of the pf matrix recovers pf for the entire channel; this implies that correlated motions between distantly-separated water molecules, as well as adjacent water molecules, influence the osmotic permeability. The pf matrices from molecular dynamics simulations of five aquaporins (AQP0, AQP1, AQP4, AqpZ, and GlpF) indicated that the reduction in the water correlation across the Asn-Pro-Ala region, and the small local permeability around the ar/R region, characterize the transport efficiency of water. These structural determinants in water permeation were confirmed in molecular dynamics simulations of three mutants of AqpZ, which mimic AQP1.

INTRODUCTION

Aquaporin (AQP) is a membrane channel protein that selectively transports water (aquaporin), or water and small neutral molecules such as glycerol (aquaglyceroporin), in response to the osmotic pressure between the two sides of the membrane (1). Since the structures of AQP1 and GlpF were solved (2,3), the unique transport characteristics of three-dimensional structures of various proteins in the AQP family have been clarified (2–12). At the same time, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations have made substantial contributions toward understanding the permeation mechanisms for water (12–20), glycerol (21–23), gases (24), and ions (25), as well as the inhibition of proton transduction (12–14,26–30).

Here, we focus on water permeability of AQP as characterized by the osmotic water permeability of a single channel pf [cm3/s], which is defined by

|

(1) |

where jw is the molar water flux of a channel [mol/s] and ΔCs is the concentration difference of impermeable molecules between the two sides of the membrane [mol/cm3] (31). In MD simulations, osmotic water permeability has been estimated by imposing driving forces (16,17). However, large driving forces are required to observe significant water permeation within the timescale of MD simulations. Recently, to overcome this problem, Zhu et al. proposed a theory for estimating the osmotic permeability, pf, from equilibrium MD simulations in the absence of a driving force (32).

As shown in Fig. 1, a and b, members of the AQP family show high sequence similarity: sequence identity ranges from 26% to 49%, increasing to 45–60% in the channel region. The three-dimensional structures of the proteins are very similar. The root mean-square displacements for Cα atoms are 1.6–2.3 Å for the whole chain, and 0.6–1.3 Å for the membrane spanning helices (Fig. 1 c). Notwithstanding the close similarity among these AQPs, they show a rather wide range of pf values (33–39). Therefore, subtle differences in side-chain structures of channel residues probably determine water permeability.

FIGURE 1.

(a) Phylogenetic tree of the human and E. coli aquaporin family, drawn using Molphy (54). Aquaporins and aquaglyceroporins are colored blue and red, respectively. The molecules considered in the present study are shaded. (b) A multiple alignment of members of the aquaporin family. Residues on the channel surface are enclosed in a frame. The NPA motifs and ar/R region are shaded in yellow and blue, respectively. Magenta corresponds to Tyr23 and Tyr149 of AQP0, which occlude the channel. The mutation sites, Leu170 and Asn182, of AqpZ are shaded in green and cyan, respectively. Asterisks indicate the residues whose main-chain oxygens protrude into the pore and form hydrogen-bonding sites for channel waters. (c) Superimposition of the aquaporins: AQP1 (green), AQP4 (pink), AqpZ (blue), GlpF (yellow), and AQP0 (magenta). This picture was prepared using PyMol (55). (d) Side view of the simulation system. The AQP1 tetramer was rendered as a cartoon representation in rainbow colors; for clarity, some helices are transparent. POPC molecules were rendered as gray sticks for aliphatic chains and as colored spheres for the headgroups: nitrogen (blue), phosphorus (orange), and oxygen (red). Water oxygen atoms are represented by cyan spheres. These diagrams were drawn using Molscript (56) with Raster3D (57). (e) Top view of the simulation system.

In a previous letter (18), we reported pf values of four members of the AQP family (AQP1, AQP0, AqpZ, and GlpF) from equilibrium MD simulations in an explicit membrane environment using the theory of Zhu et al. (32). The calculated pf values varied widely among the AQPs. Recently, Jensen and Mouritsen used the same theory to calculate the pf values of AqpZ and GlpF (19).

Although pf values calculated from simulations can be directly compared with the experimental value, the direct connection between a single quantity pf and structural details of the channel remains unclear. In this study, to better understand the structural determinants of water permeability in AQP, we propose a pf-matrix method that explicitly describes contributions from local regions of the channel to the pf value for the entire channel. Using the trajectories from the previous simulations together with new MD simulations for AQP4 (9), the pf matrix clarifies the detailed relationship between water permeation and the channel structures.

In addition to the simulations of the five AQPs, we confirmed the conclusions obtained in the wild-type AQPs by performing another series of MD simulations for three mutants: L170V, N182G, and L170V/N182G of AqpZ, mimicking AQP1, which has a similar structure to AqpZ but shows a different pf value. The pf matrices of these mutants demonstrate that even a single mutation significantly changes the permeation behavior of water through the channel.

THEORY AND METHODS

pf matrix

Here, we present the theory underlying the pf matrix. Because the pf matrix is an extension of the theory of Zhu et al. (32), we first briefly review their theory before describing the pf matrix.

The approach described by Zhu et al. provides estimates of the single-channel osmotic permeability pf from the equilibrium simulation performed in the absence of osmotic pressure. In the theory, the configuration of channel water molecules is treated by the collective coordinate n, defined in differential form as

|

(2) |

where dzk is the displacement of water k along the channel (aligned in the z direction), S(t) is the set of water molecules in the channel, and L is the length of the channel. By this definition, the net amount of water permeation can be calculated by the time average of n. Every water molecule crossing the membrane through the channel from one side to the other increases n by +1 (upward) or −1 (downward).

The molar water flux of a channel jw in Eq. 1 is simply related to the collective variable n by

|

(3) |

where vn is the velocity of n, 〈…〉1 denotes the average under osmotic pressure, and NA is Avogadro's number. According to the linear response theory, the average vn in the perturbed state under osmotic pressure is related to averages and fluctuations in the unperturbed state under no osmotic pressure as follows. The average velocity, 〈vn〉1, is approximated to the first-order by

|

(4) |

where 〈…〉0 denotes the average in the absence of osmotic pressure, U is the perturbing potential, kB is the Boltzmann constant, and T is the absolute temperature. The perturbing potential originates from the difference in the chemical potential of water, Δμ, between the two sides of the membrane. Thus, in a dilute solution, U is given by

|

(5) |

where Vw is the molar volume of water. Introducing Eq. 5 to Eq. 4, we have

|

(6) |

Here, we used 〈vn〉0 = 0. Since the average quantity 〈vnn〉0 can be related to the diffusion coefficient of n, Dn, by

|

(7) |

we obtain with the help of Eqs. 1, 3, 6, and 7,

|

(8) |

where vw = Vw/NA. This is Zhu et al.'s formula for pf (32). The diffusion coefficient is calculated from the simulation through the mean-square displacement of n as

|

(9) |

where C is a constant.

Although the pf value calculated from simulations can be directly compared with the experimental value, a single quantity pf does not explain in detail the contributions of each local channel region to water permeability. Therefore, we extended the theory to a form that explicitly describes the contributions from the local regions. The channel is subdivided into N parts, or N subchannels, with length LN (L = NLN). The collective coordinate, ni, for subchannel i is defined as

|

(10) |

where Si(t) is the set of water molecules in subchannel i (= 1,…, N). Since n = Σini/N, the mean-square displacement of n becomes

|

(11) |

where 〈ni(t)nj(t)〉0 is written in a similar manner to Eq. 9, as

|

(12) |

Moreover, Dij is also written in terms of the velocity correlation function as

|

(13) |

where vi(t) is the velocity of ni(t). The value of pf is thus divided into the local contribution pij as

|

(14) |

with

|

(15) |

We refer to the matrix of pij as the pf-matrix. Note that the diagonal element pii is the water permeability of subchannel i, and the off-diagonal element pij (i ≠ j) denotes the covariance between the water molecules in i and those in j. It is convenient to convert the diagonal and off-diagonal elements pij into the correlation coefficient cij, defined as

|

(16) |

We refer to the matrix of cij as the pf-correlation matrix.

Modeling and simulations of aquaporins

For AQP1, AQP0, AqpZ and GlpF, the trajectories from MD simulations in our previous letter (18) were used for the pf matrix analyses. In addition, we carried out MD simulations of AQP4 and three mutants of AqpZ: L170V (at the Asn-Pro-Ala, i.e., NPA region), N182G (outside the ar/R region), and L170V/N182G, mimicking AQP1. Here, we describe the modeling and simulation protocols for AQPs.

Fig. 1, d and e, shows a representative system of our simulation setup, which contains the AQP tetramer, a lipid bilayer consisting of palmitoyloleoylphosphatidylcholine (POPC), waters, and counterions. The crystal structures of the AQPs were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB): AQP1 (PDBID: 1J4N (5)), AQP4 (2D57 (9)), AqpZ (Chain A of 1RC2 (6)), GlpF (1LDI (12)), and AQP0 (1YMG (7)). A missing residue, PRO36 in 1YMG, was added using MODELLER (40) and was optimized by energy minimization. The other missing residues at the N- and C-termini were simply truncated. The coordinates of the AqpZ mutants, L170V, N182G, and L170V/N182G, were modeled manually by removing or adding several atoms, followed by energy minimization.

The POPC lipid bilayer was prepared as follows. First, 256 POPC lipid molecules were placed randomly in each leaflet, for a total of 512 POPC molecules. After the addition of waters, the system was equilibrated for 1 ns under NPAT conditions (constant surface area and constant pressure) at 300 K and 1 atm. The tetrameric form of AQP was then embedded in the POPC bilayer after removing a suitable number of lipid molecules overlapping with the protein. The position and orientation of the lipid molecules surrounding the protein were optimized by the Monte Carlo method. The system contains ∼390 lipid molecules and 30,000 waters (150,000 atoms in total), with a box size of 128.20 × 128.20 × 94.85 Å. Two copies of the system for each AQP were made, each with different lipid configurations.

All the simulations were carried out with the MD program MARBLE (41) using the CHARMM22 (42) force field corrected by CMAP (43) for proteins, CHARMM27 (44) for lipids, and TIP3P (45) for water. Electrostatic calculations were performed without a cutoff operation using the particle mesh Ewald method with periodic boundary conditions (46). The Lennard-Jones interactions were switched to zero over a range of 8–10 Å. In this study, the symplectic integrator for rigid bodies was used, treating CHx, NHx, SH, and OH groups and water molecules as rigid bodies (41). The time step was 2 fs.

The whole system was equilibrated for 400 ps, constraining the protein coordinates under NPT ensemble (300.15 K and 1 atm) conditions with a harmonic force constant of 1 kcal/mol/Å2. Subsequently, the force constant was gradually decreased to zero over 100 ps. A product run was performed under NPT ensemble conditions for 5 ns without any additional constraints. This run was repeated twice for two copies of the simulation system for each AQP. The total simulation time analyzed in this study was 80 ns (5 ns × 2 × 8).

The pf values were evaluated using Eq. 8 from the diffusion coefficient Dn calculated from the linear slope of the mean-square value of n for the time interval between 30 ps and 100 ps. The channel region was defined as −13 ≤ z ≤ 3 (i.e., channel length L = 16 Å), which is the same as the definition used in our previous letter (18). The origin of the z-axis was set to be the position of main-chain oxygen atoms corresponding to G192 of AQP1. For the pf matrices, Dij values in Eq. 12 were calculated from the linear slope of 〈ni(t)nj(t)〉0 for the time interval between 30 ps and 100 ps.

Simulation of water permeation through a carbon nanotube

To examine the ideal single-file permeation of water, we performed MD simulations of a carbon nanotube (CNT) embedded in the bilayer. A CNT 16 Å in length and 3.5 Å in radius was modeled with a chirality of (8,2) and bond lengths of 1.42 Å. The lipid bilayer was mimicked by two flat layers composed of carbon atoms. The positions of all atoms in the CNT and the bilayer were completely fixed in the simulation. The simulation system contained 806 carbon atoms, 1238 water molecules, and had the dimensions 33.0 Å × 30.9 Å × 56.0 Å. The protocol used in these simulations was the same as that described above (300.15 K, 1 atm), but instead of the NPT ensemble, the NPAT ensemble, giving a constant x-y plane surface area, was used for compatibility with the rigid CNT and bilayer. For the product run, the 2.5-ns simulation was repeated four times.

RESULTS

The pf matrices of wild-type aquaporins

For AQP4, the pf value was evaluated to be 7 ± 3 from the MD simulations performed in this study. For AQP1, AqpZ, GlpF, and AQP0, we reported the pf values (in units of 10−14 cm3/s) to be 10 ± 4, 16 ± 5, 16 ± 3, and 0.2 ± 0.2, respectively, in our previous letter (18). The diffusive permeability (pd) and the effects of the channel definitions on pf and pd for these proteins are given in the Discussion. The AQPs showed a wide range of pf values, and it is expected that differences in the channel structures would determine the pf values. However, the direct connection between the pf value and structural properties of the channel (Fig. 2) remains unclear. The pf matrix method proposed in this study facilitates understanding the contributions of the local regions to the pf value.

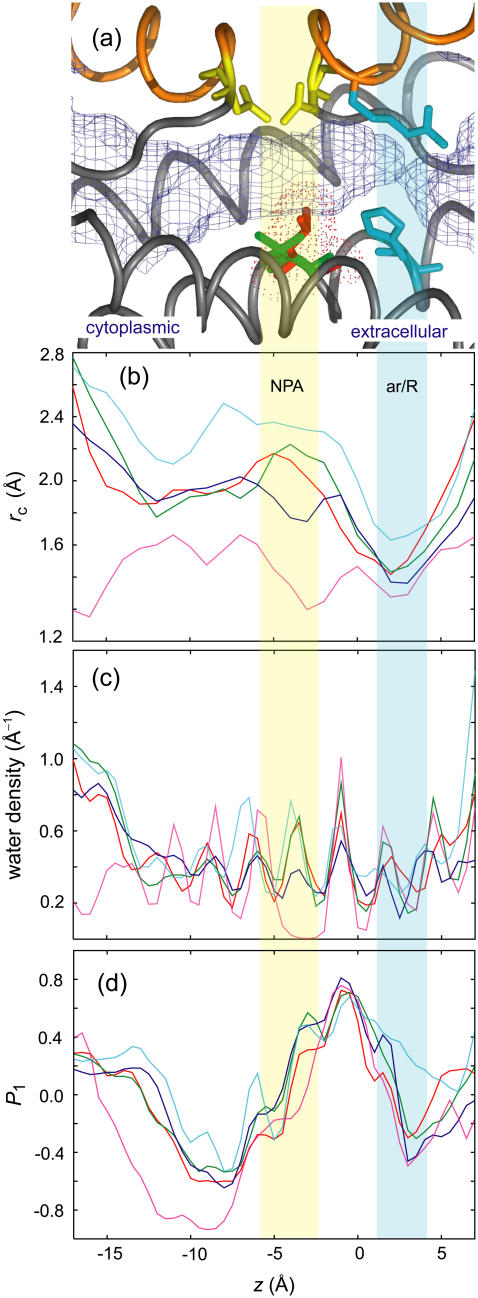

FIGURE 2.

(a) The channel region of an AQP monomer drawn using the coordinates of AQP1. The pore is represented by light-blue meshes. The NPA motifs and the ar/R region are drawn in yellow and cyan sticks, respectively. Val178 (AQP1) and Leu170 (AqpZ) are indicated by green and red sticks, respectively. The hemihelices (HB and HE) are colored orange. The z-axis is aligned to the bilayer normal with the extracellular side on the right. (b) Channel radius rc(z), AQP1 (red), AQP4 (green), AqpZ (blue), GlpF (cyan), and AQP0 (magenta), calculated by the method proposed by Smart et al. (58), which uses Monte Carlo simulated annealing to search the vacant area with a probe sphere in the x-y plane for a given z value. The radius profiles are averages over the eight monomers in the two independent 5-ns simulations. The NPA motifs and ar/R region are indicated by semitransparent yellow and cyan areas, respectively. The horizontal axis represents the z-axis. (c) Number density of channel waters. (d) Orientation of channel waters represented by the order parameter P1(z) = 〈cosθ〉, where θ is the angle between the dipole moment of water and the z-axis.

The pf matrices {pij} defined in Eq. 15 for the five AQPs are shown in Fig. 3. Here, the size of subchannel LN was set to 2 Å. The expansion of a single scalar quantity, pf, into a matrix form (the pf matrix) clearly reveals details in the permeation behavior of the AQPs. The most important feature of the pf matrix is that the average of all the elements corresponding to the channel region, including both diagonal and off-diagonal elements, equals pf (see Eq. 14). Unlike previous analyses of the correlated motion of adjacent water molecules (13,14,18,19), the formulation of the pf matrix indicates that the correlated motions of widely-separated water molecules influence osmotic permeability, as do adjacent water molecules.

FIGURE 3.

The pf matrices for the five AQPs: (a) AQP1, (b) AQP4, (c) AqpZ, (d) GlpF, and (e) AQP0. The vertical and horizontal axes are the z-axis of the channels. The same color scheme was used for all the AQPs except for AQP0. The broken lines indicate the position of the NPA motif.

In common among the AQPs, the cytoplasmic region (z < −5; see Fig. 2) makes a large contribution to pf compared with the NPA (z ∼ −4) and ar/R (z ∼ 3) regions. The off-diagonal element pij becomes smaller when subchannels i and j are separated by the NPA region. This indicates that the NPA region hinders the collective motion of the water chain: water motion at one end of the channel does not propagate to the other end. AqpZ does not show a clear interruption at the NPA region; the correlation extends beyond the NPA region, which is more like single-file permeation.

The trend in the correlation is more clearly observed in the pf correlation matrices {cij} (Fig. 4, b–f). AqpZ has the strongest correlation among the AQPs (Fig. 4 d). For comparison, an example of the ideal single-file permeation of a carbon nanotube is shown in Fig. 5. In the nanotube, all the elements of the pf correlation matrices are close to unity (Fig. 5 c). The strong correlations of the water motions in the carbon nanotube were also observed by Berezhkovskii and Hummer (47). Compared with the ideal single-file permeation of the nanotube, even in AqpZ, cij between both ends of the channel are less than unity. In the other AQPs, clear reductions in cij for subchannels i and j separated by the NPA region are observed. In particular, AQP0 has almost no correlation across the NPA region (Fig. 4 f) due to no water density around the NPA region (Fig. 2 c). The elimination of water around the NPA region is caused by the occluding side chain of Tyr23 in AQP0.

FIGURE 4.

(a) Diagonal elements pii of the pf matrix: AQP1 (red), AQP4 (green), AqpZ (blue), GlpF (cyan), and AQP0 (magenta). The pf correlation matrices: (b) AQP1, (c) AQP4, (d) AqpZ, (e) GlpF, and (f) AQP0. The vertical and horizontal axes are the z-axis of the channels. The broken lines indicate the position of the NPA motif.

FIGURE 5.

(a) A side view of a carbon nanotube (CNT) system. The carbon nanotube and the carbon sheets mimicking the lipid bilayer are represented by gray sticks. Water molecules are rendered in red and white sticks. The water molecules inside the CNT form a continuous single-file, and are connected to each other by hydrogen bonds. (b) Diagonal elements pii of the pf matrix. The pf matrix for the CNT was calculated using the 10-ns trajectory. The diagonal terms pii of the pf matrix show a flat profile. (c) The pf correlation matrix {cij}. All the cij elements of the correlation matrix are ∼1.0. These features clearly indicate the prototypical characteristics of single-file permeation.

Although AqpZ and GlpF have almost the same pf value in our simulations, the pf matrix demonstrates that the same pf value was attained by different permeation mechanisms. In AqpZ, the strong correlation (i.e., the off-diagonal elements) largely contributes to the pf value as discussed above. In contrast, GlpF has weaker correlations than AqpZ (Fig. 4 e). Instead of the correlation, the diagonal elements pii of GlpF are larger than those of AqpZ by 1.67 × 10−14 cm3/s on average (Fig. 4 a). The large pore size in GlpF (Fig. 2 b) seems to increase the local permeability (i.e., the diagonal elements pii) (Fig. 4 a) and to decrease the correlation in water motion (Fig. 4 e). Additional water molecules in a large pore appear to break one-dimensional hydrogen-bond networks to reduce the correlation between the two ends of the channel.

A surprising feature of the pf correlation matrices is that no significant reduction in correlation around the ar/R region is observed in any AQP, even in the narrowest region in the channel (Fig. 2 b). Instead of reducing correlation, the diagonal elements are small around the ar/R region compared with those of other regions (Fig. 4 a), indicating that the local permeability around the ar/R region is low. This may be due to the strong interaction between water and the protein in the ar/R region. Water-water and water-protein interactions in the ar/R region are discussed in the section describing studies on mutants of AqpZ.

In the single-file-like water permeation, it is reasonable to assume that there is a critical region that determines the pf values for the entire channel. Interestingly, the net pf values were close to the minimum values of the diagonal elements of the pf matrices, 10, 7, 15, 16, and 0.2 (in units of 10−14 cm3/s) for AQP1, AQP4, AqpZ, GlpF, and AQP0, respectively. In AQP1, AQP4, and AqpZ, the minimum points of the diagonal elements are located around the ar/R region, which is considered to be a critical region of those AQPs. In contrast, GlpF has a minimum at the NPA region (z ∼ −4), suggesting that the critical region of GlpF is different from those of other AQPs.

The remarkable differences in the pf matrices, i.e., the reduction in the correlation across the NPA region and the small local permeability around the ar/R region, were examined in terms of the relationship with their sequences and structures. As described above, AQP1 and AQP4 have weaker correlations across the NPA region than AqpZ. Although these AQPs have very similar pore sizes on average, a significant difference is found in the NPA region (Fig. 2 b). As shown in Figs. 1 b and 2 a, Leu170 in AqpZ, which protrudes into the NPA region, is replaced with smaller Val178 in AQP1 or Val197 in AQP4. As a result, the radius of this region becomes larger in AQP1 and AQP4 than in AqpZ (Fig. 2 b). Broadening of the NPA region is a possible cause of the reduction in correlation across the NPA region. Another factor that may be responsible for the differences in the pf matrices is outside the ar/R region. Asn182 of AqpZ in the extracellular region (z ∼ 6.5) is replaced by Gly190 in AQP1 or Gly209 in AQP4. As shown in Fig. 6 a, the side chain of Asn182 narrows the extracellular end of the channel. Substitution of Asn by Gly makes the channel end much wider. This broadening of the channel in AQP1 and AQP4, compared to AqpZ, may be the cause of the change in water permeability around the ar/R region. To examine these observations further, we performed in silico mutation studies by carrying out another series of MD simulations for AqpZ mutants.

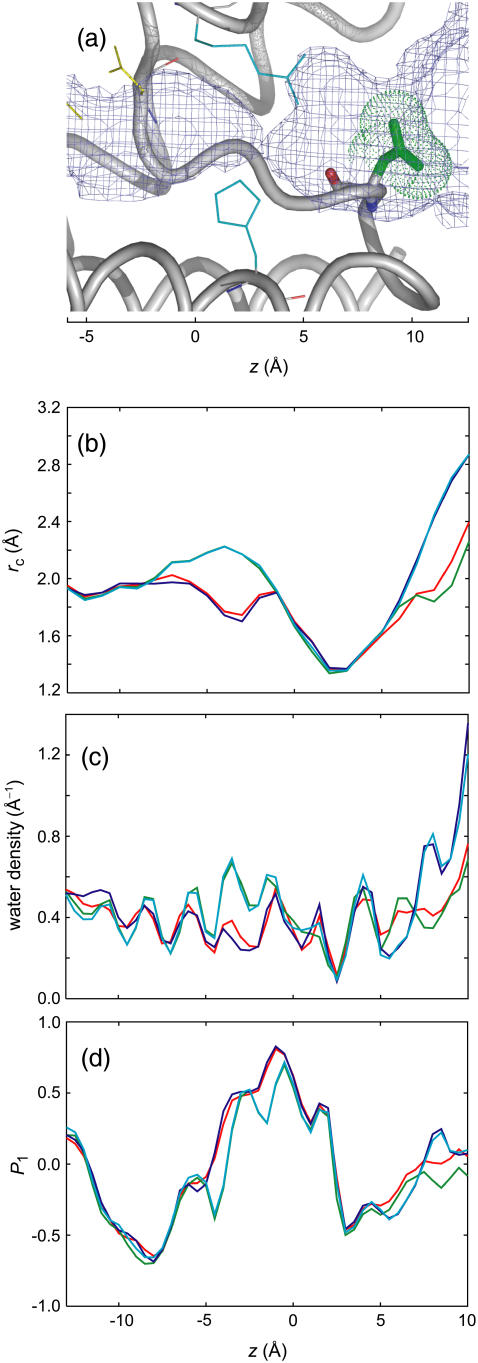

FIGURE 6.

(a) Close-up view of the extracellular side of AqpZ showing the Asn182 mutation site. Green sticks and surface dots represent the side chain and the molecular surface of Asn182, respectively. Mutation of this residue to glycine removes the side chain. (b) Channel radius rc, wild-type (red), L170V (green), N182G (blue), and L170V/N182G (cyan), calculated by the average of the eight monomers in the two independent 5-ns simulations. The NPA motifs and ar/R region are indicated in semitransparent yellow and cyan, respectively. The horizontal axis represents the z-axis. (c) Number density of channel waters. (d) The order parameter P1(z) = 〈cosθ〉, where θ is the angle between the dipole moment of water and the z-axis.

In silico mutation study of AqpZ

To confirm the observations of the pf matrices of the wild-type AQPs, in silico point mutation studies were carried out. As described above, two residues in AqpZ, L170 in the NPA region and N182 outside the ar/R region, are considered to be responsible for the differences in the pf matrices among the AQPs. L170 and N182 in AqpZ correspond to V178 and G190 in AQP1 (or V197 and G209 in AQP4), respectively. The role of these two residues in water permeation was investigated through MD simulations of three mutants of AqpZ: L170V, N182G, and L170V/N182G, mimicking AQP1. The simulation methods were the same as those for the wild-types, i.e., 5 ns × 2 simulations in the POPC bilayer. Fig. 6 b shows the average profile of the channel radii in the mutants. The mutation of L170V and N182G widened the channel radius at the NPA region and the extracellular region, respectively, and succeeded in making the structures of these regions closer to the corresponding regions of AQP1. Fig. 6 c exhibits a larger density at the NPA and extracellular regions for the mutants than for the wild-type. The simulation results for pf values are given in Fig. 7 a. The mutants have smaller pf values than does AqpZ. The decrease in pf caused by channel broadening was successfully reproduced at a qualitative level. Details of the pf matrices of the mutants are described below.

FIGURE 7.

(a) Single-channel water permeability pf of AQP1, AqpZ wild-type, and its mutants, L170V, N182G, and L170V/N182G. (b) Diagonal terms pii of the pf matrix: AQP1 (magenta), AqpZ wild-type (red), L170V (green), N182G (blue), and L170V/N182G (cyan). The pf correlation matrices of AqpZ mutants: (c) L170V, (d) N182G, and (e) L170V/N182G.

L170V

This mutation was intended to broaden the channel radius at the NPA region as in AQP1 by mutating Leu170 to Val (see Fig. 2 a). As is clearly shown in Fig. 7 c, the correlation cij across the NPA region was reduced to that similar in AQP1 (Fig. 4 b). Because the mutation caused an unexpectedly larger pore in the NPA region compared with that of AQP1 (Figs. 2 b and 6 b), the interruption of the correlation is stronger in L170V than in AQP1. The profile of diagonal elements pii in L170V is totally different from that of wild-type AqpZ and AQP1 (Fig. 7 b). The values of pii are comparable to those of the wild-type on the cytoplasmic side of the NPA region (z < −6) but show a sudden drop in the NPA region (−6 < z < −2). In the extracellular region (z > −2), including the ar/R region, the values are almost flat and as small as those of AQP1. Consequently, in L170V, the two regions separated by the NPA region have largely different local permeabilities caused by interruption of the correlation between the two regions, as shown in the pf correlation matrix (Fig. 7 c).

The rotation of the water dipole shown in Figs. 2 d and 6 d is considered to be one reason for this mutational effect. When a water molecule intrudes into the channel from the bulk water region in the cytoplasm, single-file permeation occurs as the motion of the entire water chain in the channel proceeds in the extracellular direction. During this translational motion, however, each of the water molecules has to change its direction by almost 180° when passing through the NPA region. Therefore, the translational motion has to be tightly coupled with the rotational motion. In L170V, the enlarged volume increases the degree of freedom in the channel waters, and in turn weakens the coupling between translational and rotational motions. This may be a cause of the decrease in water permeability in L170V and may explain the differences observed between AqpZ and AQP1. Actually, as shown in Fig. 6 d, the values of P1(z) indicate some interruption of the smooth rotation of waters in L170V.

N182G

This mutation enlarges the pore size at the entrance of the channel outside the ar/R region by trimming the Asn182 side chain (Fig. 6 a). The single-file-like correlation cij appearing in AqpZ was similar to that of N182G (Fig. 7 d). On the other hand, the diagonal elements pii shown in Fig. 7 b indicate an almost constant decrease by 3–5 × 10−14 cm3/s. These results suggest that the unperturbed NPA region maintained its single-file nature, and the lack of the Asn182 side chain influenced the local permeability. The effect on local permeability is discussed below in terms of water-water and water-protein interactions.

L170V/N182G

It was expected that the influence of the L170V and N182G mutations would be simply additive. However, the double mutation resulted in almost the same pf matrix (Fig. 7, b and e) as that of L170V (Fig. 7, b and c). This implies that additivity did not hold for water permeation in AQP because the single-file permeation, despite being distorted, contained complicated long-range correlations. These results show that, at least in this case, the influence of the mutation in the NPA region was dominant.

In these mutants, as in the wild-types, the net pf values were close to the minimum values of the diagonal elements pii (Fig. 7, a and b). The minimum points were located around the ar/R region, suggesting that the decrease in pf values in the mutants is due to decrease in the local permeability around the ar/R region. In the following, the mutation effects on the local permeability around the ar/R region were analyzed in terms of hydrogen bonds of waters and proteins.

Details of the hydrogen bonds between the channel waters are summarized in Fig. 8, a–d. Fig. 8 a plots the average distance between a water located at position z and its neighboring waters, and Fig. 8, b–d, gives the average number of hydrogen bonds between a water molecule and channel waters, nitrogen atoms, or oxygen atoms in AQP, respectively. In the ar/R region, the water-water distance is maximum (Fig. 8 a) and each water molecule has only one hydrogen-bonded water partner, but forms many hydrogen bonds with protein atoms (Fig. 8, b–d). In the ar/R region, therefore, the water-protein interactions are stronger than the water-water interactions, as pointed out previously (19). This is one reason why the local permeabilities around the ar/R region are small compared with those of other regions, as shown in Figs. 3 and 4.

FIGURE 8.

(a) Average distances between a water located at position z and its adjacent channel waters in AqpZ wild-type and mutants: AqpZ wild-type (red), L170V (green), N182G (blue), and L170V/N182G (cyan). (b) The average number of hydrogen bonds of a water molecule with channel waters. (c) Same as panel b, but with the nitrogen atoms of the protein. (d) With the oxygen atoms of the protein. Hydrogen-bonded pairs were defined as being within 3.5 Å of each other.

L170V has more water-water hydrogen bonds (−7 < z < 2; Fig. 8 b) and fewer hydrogen bonds with N atoms in the NPA region (−5 < z < −2; Fig. 8 c) due to the increase in pore size. Since the water-water interactions are more flexible than the water-protein interactions, L170V has a more flexible water structure than the wild-type, resulting in the decrease in water permeability. In N182G, because of the absence of the N182 side chain, we can observe the increase in water-water interactions outside the ar/R region (z > 6) and the decrease at the ar/R region (Fig. 8 b). A more important change in N182G is the increase in the distance of water-water hydrogen bonds at z ∼ 4 (i.e., the ar/R region), as shown in Fig. 8 a. This occurs as a result of the shift in optimal position of water-O hydrogen bonds from z ∼ 6.5 to ∼7.5 (Fig. 8 d). This shift occurs because the removal of the N182 side chain diminishes the peak at z = 6.5, and the main-chain oxygen atoms of N182, A117, and S118, originally masked by the N182 side chain, appear to form hydrogen bonds with water at z = 7.5. Therefore, the N182G mutation weakens water-water interactions in the ar/R region and may be a cause of the decrease in water permeability in N182G. The hydrogen-bond structure in the double mutant L170V/N182G was reproduced perfectly by the addition of the influences from the L170V and N182G mutations. However, this additivity in the structure was not necessarily reflected in the additivity in water permeability, as shown above.

DISCUSSION

Experimental values of pf (in units of 10−14 cm3/s) have been reported as 4.6 (33), 5.43 (34), 6 (35), and 11.7 (36) for AQP1, 24 (35) and 3.5–9 (estimated from membrane permeability) (48) for AQP4, 0.25 for AQP0 (35), 2 (37), and over 10 (38) for AqpZ, and 0.7 (39) and ∼2 (estimated from membrane permeability) (49) for GlpF. Taking into account the large errors in the calculated values, and the wide variety of experimental data, the amount of discrepancy between simulations and experiments is satisfactory except for GlpF. The experimental value of GlpF is nearly one order-of-magnitude smaller than the simulation values. The agreement between pf values calculated by independent MD simulations for GlpF (16,19) suggests a certain discrepancy between the condition of simulations and that of experiments. It should be noted that experimental pf values of AQPs can have large errors depending on the accuracy of the estimated number of channels in the sample. It is still challenging and difficult to determine pf values experimentally.

One of the possible limitations of the linear response formula for pf is in the presence of correlated water reentry after apparent translocation events. This is associated with the definition of the channel region, because the permeation is measured for a predefined channel region in the linear response formula. Thus, we compared the results for two channel definitions: −13 ≤ z ≤ 3 and −13 ≤ z ≤ 5 (i.e., a channel length L = 16 and 18 Å, respectively) (Table 1). The pf values calculated using the two definitions are close to each other. It is reasonable if the net pf value is determined by the minimum value of the diagonal elements of the pf matrix, as described above. Thus, the linear response expression for the pf values appears to be robust against channel definitions.

TABLE 1.

Single-channel osmotic and diffusive water permeability constants pf, pd

| L | pf | pd | pf / pd |  |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AqpZ | 16 | 15.9 ± 5.1 | 2.7 ± 1.2 | 5.8 ± 3.1 | 5.8 ± 0.3 |

| 18 | 15.6 ± 5.0 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 7.7 ± 4.6 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | |

| GlpF | 16 | 16.0 ± 2.9 | 4.6 ± 1.5 | 3.5 ± 1.3 | 6.9 ± 0.2 |

| 18 | 15.8 ± 2.8 | 3.5 ± 1.4 | 4.6 ± 2.0 | 7.8 ± 0.2 | |

| AQP1 | 16 | 10.3 ± 4.1 | 2.0 ± 1.3 | 5.3 ± 4.0 | 6.2 ± 0.2 |

| 18 | 10.1 ± 4.0 | 1.4 ± 1.0 | 7.1 ± 5.9 | 6.9 ± 0.4 | |

| AQP4 | 16 | 7.4 ± 2.6 | 1.5 ± 0.9 | 5.0 ± 3.7 | 6.1 ± 0.3 |

| 18 | 7.0 ± 2.8 | 1.0 ± 0.6 | 6.9 ± 5.0 | 6.9 ± 0.5 | |

| AQP0 | 16 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | N/A | 5.1 ± 0.2 |

| 18 | 0.2 ± 0.2 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | N/A | 5.9 ± 0.3 | |

| L170V | 16 | 13.1 ± 1.3 | 3.3 ± 0.6 | 4.0 ± 0.9 | 6.5 ± 0.2 |

| 18 | 12.4 ± 1.4 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 4.7 ± 1.1 | 7.4 ± 0.2 | |

| N182G | 16 | 12.2 ± 3.1 | 2.0 ± 0.8 | 6.1 ± 3.0 | 5.7 ± 0.2 |

| 18 | 12.0 ± 3.0 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 7.8 ± 3.8 | 6.6 ± 0.2 | |

| L170V/N182G | 16 | 14.4 ± 1.8 | 2.4 ± 0.9 | 5.9 ± 2.2 | 6.5 ± 0.2 |

| 18 | 13.7 ± 1.7 | 2.0 ± 1.0 | 7.0 ± 3.6 | 7.4 ± 0.3 |

L170V, N1822G, and L170V/N182G are mutants of AqpZ. Values of pf and pd are in units of 10−14 cm3/s.  is the average number of water molecules in the channel region. L is the channel length in Å. The channel definitions are −13 ≤ z ≤ 3 (L = 16) and −13 ≤ z ≤ 5 (L = 18). Values after “±” are standard deviations from eight monomers in two independent simulations.

is the average number of water molecules in the channel region. L is the channel length in Å. The channel definitions are −13 ≤ z ≤ 3 (L = 16) and −13 ≤ z ≤ 5 (L = 18). Values after “±” are standard deviations from eight monomers in two independent simulations.

In addition to the osmotic permeability pf, we calculated the diffusive permeability pd, which is calculated using the total number of water molecules completely permeating the channel in either direction, N±, by

|

(17) |

where nm is the number of channels, and tsim is the simulation time. The pd values are also summarized in Table 1. In contrast to pf, pd largely depends on the channel definition and length, because a longer channel would require a longer time for water molecules to pass through the channel completely.

Our pf and pd are consistent with previous MD studies imposing explicit hydrostatic pressure for GlpF (pf =14.0 ± 0.4) (16) and AQP1 (pf = 7.1 ± 0.9) (17), and with equilibrium MD studies for GlpF by Jensen et al. (pd = 1.7) (12,13) and by Jensen and Mouritsen (pf = 8.6–13.1, pd = 2.7–3.2) (19). On the other hand, for AqpZ, Jensen and Mouritsen (19) reported significantly smaller values of pf and pd (pf = 3.2–4.4, pd = 0.4–1.3) than the corresponding values in Table 1. This may be due to multiple conformations of the R189 side chain in the ar/R region (6,10,19,21). They reported a gating motion for R189, and the closed state of R189 was significantly populated during their simulations. In our simulations, however, only the open conformation of R189 was observed. The side-chain conformation of R189 was stabilized by the hydrogen bond between Nη of R189 and the backbone oxygen of A117, located in an extracellular loop between α-helices M4 and M5. Backbone dihedral angles (φ, φ) of F116 and A117 in the loop are in the αL conformation, which is crucial for stabilizing the position of the backbone oxygen in A117. Because we employed the CHARMM22 force field with map-based correction of the backbone dihedral cross terms (called CMAP) (50,51), instead of the original CHARMM22, the αL conformations of F116 and A117 were kept stable, and thus the hydrogen bond between Nη of R189 and O of A117 was maintained during the entire simulation. Therefore, the difference in the stability of the open conformation of R189 is a possible reason for the discrepancy between the two sets of pf and pd values.

For idealized single-file water transport, the continuous-time random-walk model (17,47,52) predicts that

|

(18) |

where  is the average number of water molecules in the channel. The pf/pd ratios and

is the average number of water molecules in the channel. The pf/pd ratios and  in our simulations are summarized in Table 1. The pf/pd ratios for AqpZ, AQP1, and AQP4 are comparable to

in our simulations are summarized in Table 1. The pf/pd ratios for AqpZ, AQP1, and AQP4 are comparable to  while pf/pd for GlpF is significantly smaller than

while pf/pd for GlpF is significantly smaller than  These results suggest that AqpZ, AQP1, and AQP4 provide nearly idealized single-file water transport, and that GlpF deviates from the ideal situation. These are consistent with the pf matrix analyses. Jensen and Mouritsen also showed

These results suggest that AqpZ, AQP1, and AQP4 provide nearly idealized single-file water transport, and that GlpF deviates from the ideal situation. These are consistent with the pf matrix analyses. Jensen and Mouritsen also showed  for AqpZ but not for GlpF (19), despite each of their pf and pd values for AqpZ being significantly smaller than ours, as described above. Zhu et al. estimated pf/pd = 11.9 for AQP1 from MD simulations imposing explicit driving forces (17), and Mathai et al. reported pf/pd = 13.2 for AQP1 based on experimental data (53). Because of the large dependence of pd on channel definition, as well as large errors in pf and pd, the agreement between our values and those reported previously is satisfactory.

for AqpZ but not for GlpF (19), despite each of their pf and pd values for AqpZ being significantly smaller than ours, as described above. Zhu et al. estimated pf/pd = 11.9 for AQP1 from MD simulations imposing explicit driving forces (17), and Mathai et al. reported pf/pd = 13.2 for AQP1 based on experimental data (53). Because of the large dependence of pd on channel definition, as well as large errors in pf and pd, the agreement between our values and those reported previously is satisfactory.

For the mutants of AqpZ, pf, pd, pf/pd, and  were also listed in Table 1. The L170V mutant shows significantly smaller pf/pd than

were also listed in Table 1. The L170V mutant shows significantly smaller pf/pd than  indicating that the L170V mutation distorted the single-file-like water transport observed in the AqpZ wild-type. In contrast, pf/pd for the N182G mutant are close to those of the wild-type, suggesting that the N182G mutation does not alter the single-file nature, although both pf and pd are smaller than those of the wild-type. These observations are in good agreement with the pf matrix analyses described above.

indicating that the L170V mutation distorted the single-file-like water transport observed in the AqpZ wild-type. In contrast, pf/pd for the N182G mutant are close to those of the wild-type, suggesting that the N182G mutation does not alter the single-file nature, although both pf and pd are smaller than those of the wild-type. These observations are in good agreement with the pf matrix analyses described above.

CONCLUSION

The present study proposes a pf matrix method that directly describes contributions from local regions of a water channel to the osmotic permeability pf. In the pf matrix method, the channel region is subdivided into N local regions, or N subchannels. Contributions of the local regions to pf consist of both the local permeability of the subchannels and the correlated motion of water molecules in different subchannels. The local permeability and the correlated motion correspond to diagonal and off-diagonal elements of the pf matrix, respectively. The average of all elements of the pf matrix recovers the original pf value. We emphasize that the pf matrix is different from previous analyses of the correlated motions of adjacent water molecules (13,14,18,19). The pf matrix is formulated based on the linear response theory using the collective variables ni of subchannel i. According to the formulation of the pf matrix, not only the correlations of adjacent water molecules, but also those of well-separated water molecules, contribute to the pf value for the entire channel.

We applied this method to trajectories of molecular dynamics simulations of five aquaporins: AQP1, AQP4, AQP0, AqpZ, and GlpF. The expansion of a single scalar quantity pf into matrix form clearly revealed detailed differences in the permeation behavior of aquaporins. In the pf matrices of these five aquaporins, compared with the ideal single-file permeation of a carbon nanotube, reduction in the correlated motions of water across the NPA region were observed, although the degree of reduction was different for each aquaporin. Among the five aquaporins, AqpZ had the strongest correlation and thus facilitates the single-file-like permeation of water. In contrast, GlpF had weak correlation due to its large pore size. Nevertheless, GlpF attained a large pf with high local permeability. It is interesting that no significant reduction in correlation around the ar/R region was observed in any aquaporin, despite this being the narrowest region in the channel. Instead, the local permeability around the ar/R region was low due to strong interactions between water and the protein.

Comparison of AqpZ and AQP1 (or AQP4) indicated that L170 (V178) and N182 (G190) of AqpZ (AQP1) are primarily responsible for the differences in pf values. The former is located in the NPA region, and the latter is outside the ar/R region. Three mutants of AqpZ (L170V, N182G, and L170V/N182G) were modeled and molecular dynamics simulations were carried out. The pf matrices of the mutants indicated that broadening the channel at the NPA region and outside the ar/R region consistently reduces pf, which confirms the results of the wild-type pf matrices.

The pf matrix method is an efficient and general way to analyze the osmotic permeation of water channels. This method will be applicable to other channel proteins, or to artificial channels such as those in designed carbon nanotubes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Kaoru Mitsuoka and Prof. Yoshinori Fujiyoshi for providing the coordinates of AQP4 before publication, and Dr. Yuji Sugita and Dr. Sotaro Fuchigami for valuable discussions. The simulations were performed at Tsurumi Campus of Yokohama City University, and at the Research Center for Computational Science, Okazaki.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Science and Culture of Japan.

Editor: Helmut Grubmüller.

References

- 1.Borgnia, M., S. Nielsen, A. Engel, and P. Agre. 1999. Cellular and molecular biology of the aquaporin water channels. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 68:425–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murata, K., K. Mitsuoka, T. Hirai, T. Walz, P. Agre, J. B. Heymann, A. Engel, and Y. Fujiyoshi. 2000. Structural determinants of water permeation through aquaporin-1. Nature. 407:599–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fu, D., A. Libson, L. J. Miercke, C. Weitzman, P. Nollert, J. Krucinski, and R. M. Stroud. 2000. Structure of a glycerol-conducting channel and the basis for its selectivity. Science. 290:481–486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ren, G., V. S. Reddy, A. Cheng, P. Melngyk, and A. K. Mitra. 2001. Visualization of a water-selective pore by electron crystallography in vitreous ice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:1398–1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sui, H., B. G. Han, J. K. Lee, P. Walian, and B. K. Jap. 2001. Structural basis of water-specific transport through the AQP1 water channel. Nature. 414:872–878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Savage, D. F., P. F. Egea, Y. Robles-Colmenares, J. D. O'Connell III, and R. M. Stroud. 2003. Architecture and selectivity in aquaporins: 2.5 Å x-ray structure of aquaporin Z. PLoS Biol. 1:334–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harries, W. E. C., D. Akhavan, L. J. W. Miercke, S. Khademi, and R. M. Stroud. 2004. The channel architecture of aquaporin 0 at a 2.2-Å resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 101:14045–14050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gonen, T., P. Sliz, J. Kistler, Y. Cheng, and T. Walz. 2004. Aquaporin-0 membrane junctions reveal the structure of a closed water pore. Nature. 429:193–197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiroaki, Y., K. Tani, A. Kamegawa, N. Gyobu, K. Nishikawa, H. Suzuki, T. Walz, S. Sasaki, K. Mitsuoka, K. Kimura, A. Mizoguchi, and Y. Fujiyoshi. 2006. Implications of the aquaporin-4 structure on array formation and cell adhesion. J. Mol. Biol. 355:628–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang, J., B. V. Daniels, and D. Fu. 2006. Crystal structure of AqpZ tetramer reveals two distinct Arg-189 conformations associated with water permeation through the narrowest constriction of the water-conducting channel. J. Biol. Chem. 281:454–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tornroth-Horsefield, S., Y. Wang, K. Hedfalk, U. Johanson, M. Karlsson, E. Tajkhorshid, R. Neutze, and P. Kjellbom. 2006. Structural mechanism of plant aquaporin gating. Nature. 439:688–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tajkhorshid, E., P. Nollert, M. Ø. Jensen, L. J. W. Miercke, J. O'Connell, R. M. Stroud, and K. Schulten. 2002. Control of the selectivity of the aquaporin water channel family by global orientational tuning. Science. 296:525–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jensen, M. Ø., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2003. Electrostatic tuning of permeation and selectivity in aquaporin water channels. Biophys. J. 85:2884–2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Groot, B. L., and H. Grubmüller. 2001. Water permeation across biological membranes: mechanism and dynamics of aquaporin-1 and GlpF. Science. 294:2353–2357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu, F., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2001. Molecular dynamics study of aquaporin-1 water channel in a lipid bilayer. FEBS Lett. 504:212–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhu, F., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2002. Pressure-induced water transport in membrane channels studied by molecular dynamics. Biophys. J. 83:154–160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhu, F., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2004. Theory and simulation of water permeation in aquaporin-1. Biophys. J. 86:50–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hashido, M., M. Ikeguchi, and A. Kidera. 2005. Comparative simulations of aquaporin family: AQP1, AqpZ, AQP0 and GlpF. FEBS Lett. 579:5549–5552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jensen, M. Ø., and O. G. Mouritsen. 2006. Single-channel water permeabilities of Escherichia coli aquaporins AqpZ and GlpF. Biophys. J. 90:2270–2284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han, B. G., A. B. Guliaev, P. J. Walian, and B. K. Jap. 2006. Water transport in AQP0 aquaporin: molecular dynamics studies. J. Mol. Biol. 360:285–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang, Y., K. Schulten, and E. Tajkhorshid. 2005. What makes an aquaporin a glycerol channel? A comparative study of AqpZ and GlpF. Structure. 13:1107–1118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jensen, M. Ø., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2001. The mechanism of glycerol conduction in aquaglyceroporins. Structure. 9:1083–1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jensen, M. Ø., S. Park, E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2002. Energetics of glycerol conduction through aquaglyceroporin GlpF. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 99:6731–6736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hub, J. S., and B. L. de Groot. 2006. Does CO2 permeate through aquaporin-1? Biophys. J. 91:842–848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu, J., A. J. Yool, K. Schulten, and E. Tajkhorshid. 2006. Mechanism of gating and ion conductivity of a possible tetrameric pore in aquaporin-1. Structure. 14:1411–1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Groot, B. L., T. Frigato, V. Helms, and H. Grubmüller. 2003. The mechanism of proton exclusion in the aquaporin-1 water channel. J. Mol. Biol. 333:279–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chakrabarti, N., E. Tajkhorshid, B. Roux, and R. Pomes. 2004. Molecular basis of proton blockage in aquaporins. Structure. 12:65–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chakrabarti, N., B. Roux, and R. Pomes. 2004. Structural determinants of proton blockage in aquaporins. J. Mol. Biol. 343:493–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ilan, B., E. Tajkhorshid, K. Schulten, and G. A. Voth. 2004. The mechanism of proton exclusion in aquaporin channels. Proteins. 55:223–228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, H., Y. Wu, and G. A. Voth. 2006. Origins of proton transport behavior from selectivity domain mutations of the aquaporin-1 channel. Biophys. J. 90:L73–L75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Finkelstein, A. 1987. Water Movement through Lipid Bilayers, Pores and Plasma Membranes: Theory and Reality. John Wiley and Sons, New York.

- 32.Zhu, F., E. Tajkhorshid, and K. Schulten. 2004. Collective diffusion model for water permeation through microscopic channels. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93:224501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeidel, M. L., S. Nielsen, B. L. Smith, S. V. Ambudkar, A. B. Maunsbach, and P. Agre. 1994. Ultrastructure, pharmacologic inhibition, and transport selectivity of aquaporin channel-forming integral protein in proteoliposomes. Biochemistry. 33:1606–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Walz, T., B. L. Smith, M. L. Zeidel, A. Engel, and P. Agre. 1994. Biologically active two-dimensional crystals of aquaporin CHIP. J. Biol. Chem. 269:1583–1586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yang, B., and A. S. Verkman. 1997. Water and glycerol permeabilities of aquaporins 1–5 and MIP determined quantitatively by expression of epitope-tagged constructs in Xenopus oocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 272:16140–16146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zeidel, M. L., S. V. Ambudkar, B. L. Smith, and P. Agre. 1992. Reconstitution of functional water channels in liposomes containing purified red cell CHIP28 protein. Biochemistry. 31:7436–7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pohl, P., S. M. Saparov, M. J. Borgnia, and P. Agre. 2001. Highly selective water channel activity measured by voltage clamp: analysis of planar lipid bilayers reconstituted with purified AqpZ. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:9624–9629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borgnia, M. J., D. Kozono, G. Calamita, P. C. Maloney, and P. Agre. 1999. Functional reconstitution and characterization of AqpZ, the E. coli water channel protein. J. Mol. Biol. 291:1169–1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saparov, S. M., S. P. Tsunoda, and P. Pohl. 2005. Proton exclusion by an aquaglyceroprotein: a voltage clamp study. Biol. Cell. 97:545–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sali, A., and T. L. Blundell. 1993. Comparative protein modeling by satisfaction of spatial restraints. J. Mol. Biol. 234:779–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ikeguchi, M. 2004. Partial rigid-body dynamics in NPT, NPAT and NPγT ensembles for proteins and membranes. J. Comput. Chem. 25:529–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.MacKerell, A. D., Jr., D. Bashford, R. L. Bellott, R. L. Dunbrack, Jr., J. D. Evanseck, M. J. Field, S. Fischer, J. Gao, H. Guo, S. Ha, D. Joseph-McCarthy, L. Kuchnir, K. Kuczera, F. T. K. Lau, C. Mattos, S. Michnick, T. Ngo, D. T. Nguyen, B. Prodhom, W. E. Reiher III, B. Roux, M. Schlenkrich, J. C. Smith, R. Stote, J. Straub, M. Watanabe, J. Wiorkiewicz-Kuczera, D. Yin, and M. Karplus. 1998. All-atom empirical potential for molecular modeling and dynamics studies of proteins. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102:3586–3616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mackerell, A. D., Jr. 2004. Empirical force fields for biological macromolecules: overview and issues. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1584–1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feller, S. E., and A. D. MacKerell, Jr. 2000. An improved empirical potential energy function for molecular simulations of phospholipids. J. Phys. Chem. B. 104:7510–7515. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jorgensen, W. L., J. Chandrasekhar, J. D. Madura, R. W. Impey, and M. L. Klein. 1983. Comparison of simple potential functions for simulating liquid water. J. Chem. Phys. 79:926–935. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Essmann, U., L. Perera, M. L. Berkowitz, T. Darden, H. Lee, and L. G. Pedersen. 1995. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103:8577–8593. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Berezhkovskii, A., and G. Hummer. 2002. Single-file transport of water molecules through a carbon nanotube. Phys. Rev. Lett. 89:64503–64507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jung, J. S., R. V. Bhat, G. M. Preston, W. B. Guggino, J. M. Baraban, and P. Agre. 1994. Molecular characterization of an aquaporin cDNA from brain: candidate osmoreceptor and regulator of water balance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 91:13052–13056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Borgnia, M. J., and P. Agre. 2001. Reconstitution and functional comparison of purified GlpF and AqpZ, the glycerol and water channels from Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:2888–2893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mackerell, A. D., Jr., M. Feig, and C. L. Brooks III. 2004. Extending the treatment of backbone energetics in protein force fields: limitations of gas-phase quantum mechanics in reproducing protein conformational distributions in molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 25:1400–1415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.MacKerell, A. D., Jr., M. Feig, and C. L. Brooks III. 2004. Improved treatment of the protein backbone in empirical force fields. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 126:698–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhu, F., and K. Schulten. 2003. Water and proton conduction through carbon nanotubes as models for biological channels. Biophys. J. 85:236–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mathai, J. C., S. Mori, B. L. Smith, G. M. Preston, N. Mohandas, M. Collins, P. C. van Zijl, M. L. Zeidel, and P. Agre. 1996. Functional analysis of aquaporin-1 deficient red cells. The Colton-null phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 271:1309–1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Adachi, J., and M. Hasegawa. 1996. MOLPHY, Ver. 2.3: Programs for Molecular Phylogenetics Based on Maximum Likelihood. Institute of Statistical Mathematics, Tokyo, Japan.

- 55.DeLano, W. L. 2002. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific, San Carlos, CA.

- 56.Kraulis, P. J. 1991. MOLSCRIPT: a program to produce both detailed and schematic plots of protein structures. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 24:946–950. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Merritt, E. A., and D. J. Bacon. 1997. Raster3D photorealistic molecular graphics. Methods Enzymol. 277:505–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smart, O. S., J. G. Neduvelil, X. Wang, B. A. Wallace, and M. S. Sansom. 1996. HOLE: a program for the analysis of the pore dimensions of ion channel structural models. J. Mol. Graph. 14:354–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]