Abstract

Co-ordination of catalytic Zn2+ in sorbitol/xylitol dehydrogenases of the medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily involves direct or water-mediated interactions from a glutamic acid residue, which substitutes a homologous cysteine ligand in alcohol dehydrogenases of the yeast and liver type. Glu154 of xylitol dehydrogenase from the yeast Galactocandida mastotermitis (termed GmXDH) was mutated to a cysteine residue (E154C) to revert this replacement. In spite of their variable Zn2+ content (0.10–0.40 atom/subunit), purified preparations of E154C exhibited a constant catalytic Zn2+ centre activity (kcat) of 1.19±0.03 s−1 and did not require exogenous Zn2+ for activity or stability. E154C retained 0.019±0.003% and 0.74±0.03% of wild-type catalytic efficiency (kcat/Ksorbitol=7800±700 M−1· s−1) and kcat (=161±4 s−1) for NAD+-dependent oxidation of sorbitol at 25 °C respectively. The pH profile of kcat/Ksorbitol for E154C decreased below an apparent pK of 9.1±0.3, reflecting a shift in pK by about +1.7–1.9 pH units compared with the corresponding pH profiles for GmXDH and sheep liver sorbitol dehydrogenase (termed slSDH). The difference in pK for profiles determined in 1H2O and 2H2O solvent was similar and unusually small for all three enzymes (≈+0.2 log units), suggesting that the observed pK in the binary enzyme–NAD+ complexes could be due to Zn2+-bound water. Under conditions eliminating their different pH-dependences, wild-type and mutant GmXDH displayed similar primary and solvent deuterium kinetic isotope effects of 1.7±0.2 (E154C, 1.7±0.1) and 1.9±0.3 (E154C, 2.4±0.2) on kcat/Ksorbitol respectively. Transient kinetic studies of NAD+ reduction and proton release during sorbitol oxidation by slSDH at pH 8.2 show that two protons are lost with a rate constant of 687±12 s−1 in the pre-steady state, which features a turnover of 0.9±0.1 enzyme equivalents as NADH was produced with a rate constant of 409±3 s−1. The results support an auxiliary participation of Glu154 in catalysis, and possible mechanisms of proton transfer in sorbitol/xylitol dehydrogenases are discussed.

Keywords: alcohol dehydrogenase, catalysis, medium-chain dehydrogenases/reductases, proton relay, zinc ligand

Abbreviations: ADH, alcohol dehydrogenase; KIE, kinetic isotope effect; MDR, medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase; PDH, polyol dehydrogenases; SDH, sorbitol dehydrogenase (D-sorbitol:NAD+ 2-oxidoreductase, EC 1.1.1.14); slSDH, sheep liver SDH; SEC, size-exclusion chromatography; XDH, xylitol dehydrogenase (xylitol:NAD+ 2-oxidoreductase, EC 1.1.1.9); GmXDH, XDH from Galactocandida mastotermitis

INTRODUCTION

The MDRs (medium-chain dehydrogenases/reductases) constitute a large superfamily of basically two protein types, with and without Zn2+. They are comprised of different Zn2+-dependent ADHs (alcohol dehydrogenases), historically exemplified by enzymes of the yeast and liver type [1,2]. Among these ADHs, the PDHs (polyol dehydrogenases) and related forms establish a distinct enzyme family and include as their main activities, SDH (sorbitol dehydrogenase; EC 1.1.1.14) and XDH (xylitol dehydrogenase; EC 1.1.1.9) [1,2].

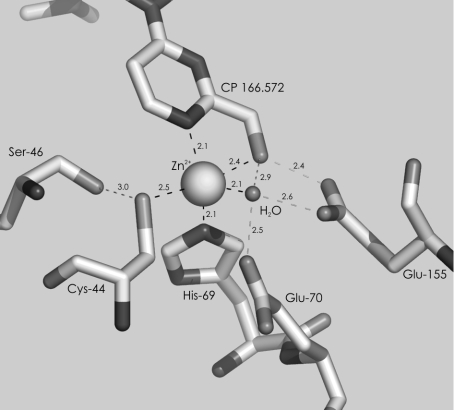

PDHs are functional homotetramers in which each subunit contains a single Zn2+ that is bound in the active site and is required for catalysis [3]. The ligand field of Zn2+ in PDHs differs from that of horse liver [4] and yeast ADH (PDB code: 2HCY) where a conserved triad of two cysteine residues and one histidine residue constitutes, together with a water molecule, the primary co-ordination sphere. Residue Cys174 (using the horse liver enzyme numbering) is replaced by a glutamic acid residue (position 155 in human liver SDH) which is conserved among the PDHs [3,4]. X-ray structures of human liver SDH [5] and the related NADP(H)-dependent whitefly ketose reductase [6] [which, like the NAD(H)-dependent SDHs, catalyses the interconversion of sorbitol and fructose, however, with a preference for keto group reduction] reveal that this glutamic acid residue is not a ligand to the Zn2+, but co-ordinates the metal ion via a water molecule (Figure 1). In contrast, a 3.0 Å (1 Å=0.1 nm) structure of rat liver SDH determined the glutamic acid residue to be linked directly [7], consistent with suggestions from earlier mutagenesis data for the same enzyme [8] and electronic absorption studies of human and sheep liver SDHs [9,10]. Another glutamic acid residue (position 70 in human SDH) is a Zn2+ ligand in all three PDH structures, whereas the corresponding Glu68 of horse liver ADH is not co-ordinating in resting enzyme complexes [11]. However, computational studies suggest that Glu68 could co-ordinate transiently during catalysis, allowing product release to take place efficiently [12]. The structure of human liver SDH bound with NADH and an inhibitor that is competitive against fructose shows that the inhibitor chelates the Zn2+ through an oxygen and a nitrogen atom and that Glu70 is dissociated from the now pentaco-ordinated metal ion [5].

Figure 1. Participation of Glu155 in Zn2+ co-ordination by human liver SDH.

The figure was derived from the 2.0 Å crystal structure of enzyme bound with NADH and an inhibitor (PDB: 1PL6) [5]. Residues within a 4 Å distance to Zn2+ are depicted. Black and grey dashed lines indicate co-ordination to Zn2+ and hydrogen bonding respectively.

What is the exact role of the positional exchange Cys→Glu in the Zn2+ ligand field of PDHs compared with that of ADHs? As proposed originally by Eklund et al. [4], a strong hydrogen bond between the negatively charged glutamic acid side chain and the primary hydroxy group adjacent to the secondary hydroxy group undergoing reaction could be an essential element of PDH-specific substrate-binding recognition and catalysis. The X-ray structure of the inhibitor complex of human liver SDH [5] (Figure 1) supports this notion by showing a very short distance (2.4 Å) between the side chain of Glu155 and the primary hydroxy group on the inhibitor which is also in co-ordination distance to the Zn2+ (2.4 Å). Kinetic evidence for a Glu→Cys variant of rat SDH, reported by Karlson and Höög [8], is also consistent with a major function of glutamic acid in substrate binding because the site-directed replacement caused a large (500-fold) decrease in sorbitol binding affinity (Ksorbitol), whereas the catalytic centre activity (kcat) of the mutant was even ≈4 times higher than that of the wild-type. In another study of slSDH (sheep liver SDH), analogues of sorbitol in which the C1 hydroxy group was replaced with a hydrogen, amino or thiol group were converted with an efficiency of between 0.36% to 4.8% of kcat/Ksorbitol at pH 7.4 [13]. The effect of substrate modification on decreasing kcat/K was mainly due to an increase in apparent K, also suggesting that the hydroxy group of sorbitol is required for binding. A second possibility is that the replacement of the thiol group ligand in ADH by a carboxy [7] or a H2O/hydroxy group ligand [5] in PDH alters the electrophilic character of Zn2+ and therefore, changes the propensity of the metal ion to bind alcohol and stabilize the proposed alkoxide intermediate state of the reaction through inner-sphere co-ordination. Relevant information could come from kinetic studies, including KIEs (kinetic isotope effects) and pH dependencies for the enzymatic reactions, as has been shown in earlier studies on ADH [14].

In the present study we report on the functional consequences of replacing Glu154 of GmXDH (XDH from the yeast Galactocandida mastotermitis) with a cysteine residue. GmXDH is a representative microbial member of MDR-type PDHs and catalyses the NAD+-dependent oxidation of xylitol into D-xylulose, this reaction representing the second step of the catabolic pathway for xylose in the yeast [15]. The Glu154 of GmXDH is homologous in the sequence to Glu155 of human SDH (see Supplementary Figure S1 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/404/bj4040421add.htm). We also describe a detailed steady-state kinetic comparison, using results of pH and KIE studies, of wild-type and E154C forms of GmXDH with the well-characterized slSDH [3,16,17]. The evidence obtained supports a role for Glu154 as a modulator of, but not its direct participation in, general base catalysis to enzymatic alcohol oxidation. Zn2+-bound water, through which Glu154 is possibly linked with the catalytic metal, would be a likely candidate to fulfil the function of the catalytic base. The glutamic acid residue is additionally important, but not essential, for substrate binding. Analysis of transient reactions catalysed by slSDH suggests a kinetic scenario for the proton transfer involved in the catalytic mechanism, and possible routes of proton exchange between enzyme and bulk solvent are discussed.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials

Unless mentioned otherwise, all materials and chemicals have been described elsewhere [18]. 2H2O solvent (99.9% 2H) and D-sorbitol were from Sigma–Aldrich. [2-2H]D-sorbitol was prepared by enzymatic reduction of D-fructose according to a protocol reported previously [18]. Unlabelled reference material was synthesized in exactly the same way. [1H] and [2H]sorbitol contained a small amount of unreacted D-fructose (≈8%), as shown by HPLC analysis with a Bio-Rad HPX-87C column operated at 80 °C using water as eluent, and refractive index detection. Deuterium labelling at position 2 of sorbitol was estimated by NMR to be ≥99%. slSDH was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (# S-3764) and used without further purification.

Mutagenesis and enzyme production

E154C is a GmXDH mutant in which Glu154 is replaced by a cysteine residue. Numbering for GmXDH starts with 1 for the initiator methionine. The site-directed mutation Glu154→Cys was introduced with the PCR-based overlap extension method [19] using the plasmid vector pBTac1 [20] containing the gene encoding wild-type GmXDH as the template. Briefly, two fragments of the target gene sequence were amplified with Synergy DNA polymerase (Genecraft) in separate PCR reactions. Each reaction used one flanking primer carrying the appropriate restriction site (indicated in bold) that hybridized at one end of the target sequence: primer 1, 5′-CCGAAACAGAATTCATGTCTA-3′; primer 2, 5′-GTCGACGGATCCTTACTC-3′; and one internal primer that hybridized at the site of the mutation and contained the mismatched bases (indicated by underlining): primer 1, 5′-CTTAAAGGACAAACTAAAGC-3′; primer 2, 5′-GCTTTAGTTTGTCCTTTAAG-3′. After extension and amplification of the overlapping fragments, the resulting construct was digested with EcoRI and BamHI, and the desired band was gel-purified and subcloned into the appropriatly digested expression vector. Plasmid mini-prep DNA was sequenced to verify that the desired mutation had been introduced and that no misincorporation of nucleotides had occurred as a result of DNA polymerase errors. Recombinant wild-type and mutant proteins were produced in Escherichia coli JM 109 transformed with the respective expression plasmid. Wild-type GmXDH was purified as described elsewhere [18]. E154C was isolated using a modified two-step procedure consisting of dye-ligand affinity chromatography followed by preparative gel filtration. To avoid contamination of E154C by wild-type enzyme, all purifications of the mutant were carried out with Procion Red HE3B (Red 120) freshly immobilized on Sepharose 4B-CL. Fractions of eluted protein containing XDH activity were brought to 50 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.0), and concentrated by ultrafiltration. Aliquots of 200 μl of a ∼10 mg/ml solution of E154C were loaded on a Superdex 200 SEC (size-exclusion chromatography) column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0). Both the applied sample and the elution buffer contained 2 mM NAD+ to stabilize the enzyme during SEC.

Steady-state kinetic studies

Initial rates of NAD+-dependent sorbitol oxidation were determined by measuring the increase in absorbance at 340 nm with a Beckman DU-650 spectrophotometer at 25 °C. The enzyme was diluted in the assay such that a plot of absorbance against reaction time was linear for at least 1 min. Reactions were always started by adding the enzyme. If not stated otherwise, a 100 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pH 9.0) was used. Apparent kinetic parameters were determined at a constant saturating concentrations of sorbitol (300 mM for GmXDH, 25 mM for slSDH and 2 M for E154C) or NAD+ (10 mM for all enzymes), and various concentrations of NAD+ or sorbitol. In the presence of a saturating NAD+ level, wild-type GmXDH and slSDH showed partial substrate inhibition at sorbitol concentrations of >300 mM and >24 mM respectively. The reported kinetic parameters of GmXDH and slSDH are from measurements at non-inhibiting substrate concentrations, covering the range 0.1–15 times and 0.1–8 times the apparent Km for sorbitol respectively.

pH and kinetic isotope effects

pL-dependences (where L is 1H or 2H) of kinetic parameters for sorbitol oxidation by wild-type enzymes and the E154C mutant were determined in 1H2O or 2H2O solvent. If not stated otherwise, a solution containing the dry buffer components indicated below was prepared and titrated to the desired pL, using NaOL or LCl. The p2H was determined using the relation p2H=pH meter reading+0.4 [21]. Alternatively, deuterated buffer was prepared by 1H→2H exchange whereby protonic buffer mixture alone (100 mM Mes and 100 mM Tris) or containing 10 mM NAD+ was taken to dryness by freeze-drying, and salts were redissolved in 2H2O immediately prior to use. Thus the p2H values of prepared deuterated buffers differed from those of the corresponding protonic buffers that were treated in exactly the same way by 0.6 pL units.

The pL-dependence studies for slSDH and GmXDH were performed in the pL range 5.2–9.0 using buffer mixtures of 100 mM Mes and 100 mM Tris. Variation in ionic strength across the chosen pL range was small (I≈0.10 M), and control experiments in which 25 mM NaCl was added to the assays revealed the absence of significant ionic strength effects under the conditions used. The pL-dependence of E154C was analysed in the pL ranges 7.1–9.0 and 9.0–10.0 using 100 mM Tris and 100 mM glycine respectively. Ionic strength effects were not controlled. However, rate measurements in the presence of 25 mM NaCl and the agreement between kinetic parameters determined in Tris and glycine buffers (at pL 9.0), suggest that the observable pH-dependence was not strongly affected by relevant changes in ionic strength. All initial rates were recorded at various concentrations of sorbitol in the presence of 10 mM NAD+. The reactions were started by adding 10 μl of enzyme (2% of total volume of assay) from a concentrated protein stock solution in 20 mM Tris/HCl buffer (pL 7.5). For use in 2H2O, the enzymes were gel-filtered employing deuterated 20 mM Tris/HCl buffer and allowed to equilibrate with solvent for 0.5 h before the initial-rate measurement. Although the completeness of 1H→2H exchange at protonic sites on the enzymes was not controlled, it was shown that extension of the equilibration time in deuterated solvent from 0.5 to 10 h did not affect the activity and therefore solvent KIEs (see below). Because of concerns regarding enzyme stability, exchange of protein protons for deuterons via freeze-drying was not considered. Michaelis–Menten parameters were calculated from initial rates measured at each value of pL, and data obtained in 1H2O and 2H2O were treated separately. Solvent KIEs on kinetic parameters were obtained from different sets of experiments.

For determination of KIEs, initial rates of sorbitol oxidation with unlabelled and deuterium-labelled sorbitol substrate or solvent were compared under exactly identical conditions. Because the presence of ≈8% fructose in the enzymatically prepared [1H]sorbitol did not affect kinetic parameters of wild-type enzymes, in comparison with results obtained with commercial sorbitol, the level of contamination in unlabelled and deuterium-labelled sorbitol was assumed to be compatible with the determination of primary deuterium KIEs. Solvent KIEs were determined under conditions in which the enzymatic rate (v) was independent of pL where dv/dpL≈0. Calculation of KIEs on kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol was performed according to the method of Cook and Cleland [22].

Stopped-flow measurements

Rapid mixing stopped-flow experiments were carried out at 25 °C using an Applied Photophysics SX.18MV Stopped-Flow Reaction Analyser equipped with a 20 μl flow cell giving a path-length of 1 cm. The enzyme was gel-filtered twice to a reaction buffer (pH 8.0) composed of 0.5 mM Tris/HCl, 3.2 μM Phenol Red, 10 mM NAD+ and 59 mM NaCl. The ionic strength of this buffer equalled that of 100 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.0). The substrate solution contained 60 mM sorbitol dissolved in reaction buffer lacking enzyme. Transient reactions were started by mixing 100 μl of solution containing the pre-formed enzyme–NAD+ complex (6–16 μM slSDH) with 100 μl of substrate solution, and the time course of formation of NADH or proton release was monitored at 340 nm or 556 nm respectively. Data acquisition was performed with Applied Photophysics software. Under the conditions used, the instrument had a dead time of approximately 1.5 ms. Appropriate controls lacking either slSDH or sorbitol were recorded under exactly the same conditions. Calibration of the Phenol Red pH indicator was performed by titrating the reaction buffer with HCl. A plot of absorbance change at 556 nm against the proton concentration was linear, within a 95% confidence interval, in the range of 1–100 μM protons with a slope value of 430 M−1·cm−1.

Data processing

Parameter values were calculated by fitting the appropriate equation to the data, using non-linear least squares regression analysis with the SigmaPlot 2001 program version 7.0. Eqn (1) describes a mechanism with one ionizable group where both protonated and unprotonated forms can react. Y is a kinetic parameter, kL and kH are limiting values at low and high pH respectively and kH>kL, K is an apparent acid dissociation constant and is the point where Y has the average value of kL and kH, and [H+] is the proton concentration. Eqn (2) describes a simple mechanism in which one ionizable group has to be unprotonated to be active and the highest activity is attained at kH [23].

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

|

(3) |

|

(4) |

Eqn (3) describes linear competitive inhibition where [I] is the inhibitor concentration and Ki is the apparent dissociation constant of I. [E] was calculated from a molecular mass of the enzyme subunit of 37.8 kDa and was based on measurements of protein concentration (slSDH) or the concentration of Zn2+ associated with the protein preparation (GmXDH; E154C). Eqn (4) was used to fit the pre-steady state and steady-state phases of multiturnover time traces recorded in stopped-flow experiments [24]. Data recorded at 340 nm and 556 nm were converted into [NADH] and [H+] using molar extinction coefficients of 6220 M−1·cm−1 and 4307 M−1·cm−1 respectively. kobs and Π represent the transient rate constant and the product burst respectively; kss corresponds to the steady-state rate constant, t is the reaction time and Y0 is the starting point of reaction.

Other methods

Metal analysis of protein samples was performed with inductively coupled plasma MS, as described previously [15]. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad dye-binding assay.

RESULTS

Characterization of E154C

Purification of E154C from the E. coli cell extract required a protocol different from that utilized for isolation of the wild-type [18]. Results are summarized in Supplementary Table S1 (at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/404/bj4040421add.htm), and elution profiles of E154C during dye-ligand chromatography and the subsequent SEC are shown in Supplementary Figures S2 and S3 (at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/404/bj4040421add.htm) respectively. E154C was obtained with an overall yield of ≈62%. The presence of 2 mM NAD+ was essential to prevent enzyme inactivation during SEC. Supplementary Figure S4 (at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/404/bj4040421add.htm) shows SDS/PAGE analysis of purified E154C. The apparent molecular mass of the subunit of E154C was 38.7 kDa, which is in agreement with a molecular mass of 37.4 kDa calculated from the amino acid sequence.

Purified E154C eluted from an analytical gel-filtration column as a single protein peak with an apparent molecular mass of 160 kDa that contained all of the applied protein and enzyme activity. In a similar manner to the wild-type, the mutant seemed to be a functional homotetramer. Different preparations of E154C (n=4) that appeared homogeneous in SDS/PAGE (see Supplementary Figure S4 at http://www.BiochemJ.org/bj/404/bj4040421add.htm) contained between 0.1 and 0.4 atom Zn2+/protein subunit. Although the source of this variable Zn2+ content remained unknown, the activity of E154C solutions based on the molarity of Zn2+-containing active sites was constant across the different enzyme preparations. Exogenous Zn2+ (added as ZnSO4) in the concentration range 1–100 μM was a strong irreversible inhibitor of wild-type and the mutant, the IC50 value of about 5±1 μM being identical for both enzymes. Note that E154C was stable during the initial rate assays described below, suggesting that inactivation due to release of the active-site Zn2+ did not occur in the time-span of the kinetic experiments.

Kinetic parameters for sorbitol oxidation by GmXDH and E154C (corrected for the gram equivalent of bound Zn2+) are summarized in Table 1 along with the corresponding parameters for slSDH. Values of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol for E154C were 0.74±0.03% and 0.019±0.003% of the corresponding wild-type values. However, the Michaelis–Menten constant for NAD+ was the same, within limits of experimental error, in wild-type and E154C forms of GmXDH. slSDH differed from GmXDH mainly in the value of Ksorbitol which was about one order of magnitude higher in the yeast enzyme.

Table 1. Kinetic parameters of slSDH, GmXDH and E154C mutant for NAD+-dependent oxidation of sorbitol determined at pH 9.0 and 25.0±0.1 °C.

*Calculation of kinetic parameters for GmXDH and E154C is based on the molarity of Zn2+-bound protein subunits.

| Parameter | E154C* | GmXDH* | slSDH |

|---|---|---|---|

| kcat (s−1) | 1.19±0.03 | 161±4 | 28±1 |

| Ksorbitol (mM) | 785±82 | 21±2 | 3.0±0.2 |

| kcat/Ksorbitol (M−1·s−1) | 1.5±0.2 | 7800±700 | 9500±700 |

| KNAD+(μM) | 290±35 | 430±40 | 500±99 |

| kcat/KNAD+(M−1·s−1) | 4100±510 | 3.7×105±4×104 | 5.7×104±1.1×104 |

pL-dependence studies

pL profiles of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol for slSDH and GmXDH are shown in Figures 2(A)–2(C). With the exception of the pL profile for kcat of GmXDH (results not shown) which exhibited a complex pL-dependence that was not further pursued, all other pL profiles were sigmoidal, showing a decrease in rate from a constant value at high pH to a smaller constant value at low pH. These values were fitted with Eqn (1), and the results are presented in Table 2. The pL profiles of kcat/Ksorbitol for E154C in 1H2O and 2H2O also displayed a decrease in rate at low pL but, unlike wild-type GmXDH and slSDH, the activity of the mutant was lost completely below pK (Figure 2D). The data were fitted with Eqn (2), and results are presented in Table 2. The pL profiles were obtained with an experimental design in which determination of kinetic parameters was performed at several pL values that were, however, always the same in 1H2O and 2H2O. The solvent isotope effect on buffer pK implies that the buffer ratio was different in the two solvents at each pL of measurement [25]. To clearly demonstrate that these pL profiles were valid, we recorded kinetic parameters of GmXDH at different buffer ratios that were constant in 1H2O and 2H2O. Results are shown in Figure 2(C), superimposed on the data obtained using constant-pL measurements. Also note that because full pL-rate profiles were recorded with each enzyme, the solvent isotope effect on buffer pK will not interfere with determination of pK values for the enzymatic reactions in 1H2O and 2H2O.

Figure 2. pL profiles of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol for slSDH and of kcat/Ksorbitol for wild-type and E154C mutant forms of GmXDH.

● and ○ indicate measurements in 1H2O and 2H2O solvent respectively. Error bars give the S.D. of the respective kinetic parameter, and lines are non-linear fits of the data with the appropriate equation (see Table 2). In (C), △ indicates measurements with deuterated buffers that had been prepared through 1H → 2H exchange via freeze-drying. ▲ Shows corresponding measurements in 1H2O. Insets show double-log plots of the data to illustrate differences in the shape of the pL profiles at low pH, (C), sigmoidal; (D), non-sigmoidal.

Table 2. pK values from pL profiles for slSDH, GmXDH and E154C mutant.

pL profiles of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol for slSDH and GmXDH were fitted with Eqn (1). pL profiles of kcat/Ksorbitol for E154C were fitted with Eqn (2). n.d., not determined. *Superscripts indicate measurements in 1H2O (1H2O) and 2H2O (2H2O); †correlation coefficients from non-linear regression analysis are given in parenthesis.

| log (Parameter)* | pK | Limiting values (s−1; M−1·s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| slSDH | ||

| kcat1H2O | 7.10±0.15 (0.99)† | kL=3.5±0.3 |

| kH=26±2 | ||

| kcat2H2O | 7.3±0.3 (0.96) | kL=3.1±0.4 |

| kH=13±1 | ||

| (kcat/Ksorbitol)1H2O | 7.15±0.05 (0.999) | kL=75±11 |

| kH=8980±245 | ||

| (kcat/Ksorbitol)2H2O | 7.3±0.1 (0.99) | kL=69±21 |

| kH=6813±533 | ||

| GmXDH | ||

| kcat1H2O | n.d. | - |

| kcat2H2O | n.d. | - |

| (kcat/Ksorbitol)1H2O | 7.4±0.1 (0.99) | kL=17±8 |

| kH=6484±351 | ||

| (kcat/Ksorbitol)2H2O | 7.6±0.1 (0.99) | kL=11±4 |

| kH=4275±406 | ||

| E154C | ||

| (kcat/Ksorbitol)1H2O | 9.1±0.3 (0.995) | k=4.1±0.5 |

| (kcat/Ksorbitol)2H2O | 9.3±0.2 (0.99) | k=2.6±0.2 |

KIE studies

Table 3 summarizes primary deuterium KIEs on kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol for reactions catalysed by slSDH as well as wild-type and E154C forms of GmXDH at pH 9.0. KIEs on kinetic parameters of GmXDH at pH 7.5 are also shown in Table 3. Solvent KIEs were measured at pL 9.0 (slSDH, wild-type GmXDH) or pL 10.0 (E154C) where pL profiles of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol approach plateau values and thus differences in pL profiles of the respective kinetic parameter in 1H2O and 2H2O are eliminated (wild-type GmXDH; slSDH) or minimized (E154C). Instability of E154C precluded initial rate measurements at pL>10.0. The solvent KIE on the apparent dissociation constant of the binary complex of slSDH and NADH (KiNADH) was determined from initial rate studies in 1H2O and 2H2O where NADH was used as product inhibitor of the NAD+-dependent oxidation of sorbitol. Under conditions in which [NAD+] was varied and [sorbitol] was constant and saturating, NADH was a linear competitive inhibitor against NAD+. The value of KiNADH in 1H2O and 2H2O, obtained from fits of Eqn (3) to the data, was 20±4 μM and 10±2 μM respectively, yielding a solvent KIE on KiNADH of 2.0±0.6 (=20/10).

Table 3. Primary 2H and solvent KIEs on kinetic parameters for sorbitol oxidation by slSDH, GmXDH and E154C at pL 9.0 and 25.0±0.1 °C.

*Superscripts D and D2O indicate primary and solvent 2H KIEs respectively. n.a, not analysed. ‡primary deuterium KIEs determined at pH 7.5; §determined at pL 10.0.

| Parameter* | E154C | GmXDH | slSDH |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2Hkcat | n.a. | 1.16±0.03 (1.1±0.1)‡ | 1.13±0.08 |

| 2Hkcat/Ksorbitol | 2.4±0.2 | 1.20±0.07 (1.9±0.3)‡ | 1.25±0.14 |

| 2Hkcat/KNAD+ | n.a. | 1.2±0.1 | 0.9±0.2 |

| 2H2Okcat | n.a. | 1.49±0.05 | 2.1±0.1 |

| 2H2Okcat/Ksorbitol | 1.7±0.2§ | 1.7±0.1 | 1.5±0.3 |

| 2H2Okcat/KNAD+ | n.a. | 1.1±0.1 | 1.0±0.2 |

Transient kinetics

Results of KIE studies suggested that slSDH was the most practical enzyme with which to perform transient kinetic experiments. Because Dkcat and Dkcat/Ksorbitol (where D denotes the primary deuterium KIE on the respective parameter) were similar at pH 9.0, the dissociation constant of sorbitol from slSDH–NAD+ cannot be much higher than Ksorbitol (=3.0 mM). Rapid mixing of a concentrated sorbitol solution (≥100 mM) with a solution of the enzyme in reaction buffer lacking NAD+ produced high absorbance noise at 340 nm during the first 4 ms, probably because of differences in viscosity of the two solutions. Using slSDH and a sorbitol concentration of 60 mM, we could achieve full saturation of the enzyme in the steady state and, at the same time, avoid the long effective dead times. This would have not been possible with wild-type and E154C forms of GmXDH.

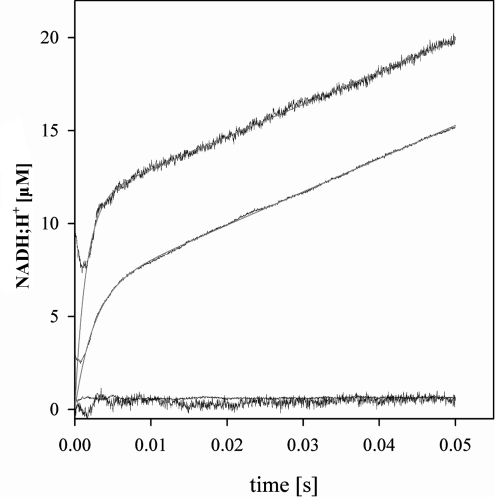

Figure 3 shows typical stopped-flow progress curves of NADH production and proton release, recorded by the increase of A340nm and the decrease in A556nm respectively, obtained under conditions of limiting concentration of slSDH (8 μM) that allowed multiple turnover of the enzyme present. Pre-formed enzyme–NAD+ was used, and the concentrations of NAD+ and sorbitol were saturating. Both time courses exhibited burst kinetics where an initial exponential increase in product formation during the first 6–10 ms was followed by a steady-state rate of product appearance, which in the case of NADH production was in excellent agreement with expectations from results of initial rate studies. The proton release rate in the steady state was identical with that of coenzyme reduction, as required by the enzymatic reaction studied, sorbitol+NAD+→fructose+NADH+H+. The multiple turnover progress curves were fitted with Eqn (4), yielding apparent first-order rate constants of 409±3 s−1 and 687±12 s−1 for NADH production and proton loss respectively. In the burst phase, 0.9±0.1 enzyme equivalents of NADH were produced. The enzyme equivalent of protons released in the pre-steady state was 1.8±0.2, hence twice that of NADH. Note that the reported values are averages from seven independent stopped-flow experiments.

Figure 3. Stopped-flow progress curves of formation of NADH and release of proton during NAD+-dependent oxidation of sorbitol catalysed by slSDH.

Traces with the higher signal-to-noise ratio are proton release measurements. Non-linear fits of the individual progress curves with Eqn (4) are shown as grey lines. Controls in which sorbitol was lacking and no reaction took place are also shown.

DISCUSSION

The Zn2+ centre of human liver SDH differs from that of horse liver ADH mainly in the substitution of the Cys174 ligand [4] by a water molecule linked through the secondary sphere Glu155 [5]. (In the discussion that follows we do not consider a role for the glutamic acid residue in directly co-ordinating the Zn2+, as suggested by the 3.0 Å structure [7] and mutagenesis data of the closely related SDH from rat [8].) Little is known about how the primary co-ordination sphere of the active-site Zn2+ influences the various steps in the catalytic mechanism of these two, and related, MDR enzymes. We have therefore substituted the relevant Glu154 of GmXDH with cysteine residues to mimic in the sequence the Zn2+ ligation pattern of ADH and carried out a detailed kinetic comparison of wild-type and E154C mutant enzymes using pH and deuterium KIE studies. To establish relationships between microbial XDH and mammalian SDH with regard to reaction mechanism, we examined slSDH in a parallel series of kinetic experiments. Purified E154C was shown to have retained a functional Zn2+ centre that displayed fractional saturation with Zn2+ of ≤0.4. The catalytic efficiency of the mutant for NAD+-dependent oxidation of sorbitol at pH 9.0 was decreased 103.7-fold in comparison with the corresponding wild-type value, suggesting that Glu154 is relatively more important for catalytic function than Zn2+ binding.

pL-dependences of wild-type enzymes and E154C

kcat for slSDH and kcat/Ksorbitol for GmXDH and slSDH in 1H2O and 2H2O displayed sigmoidal pH-dependences with level asymptotes at high and low pH. There are several mechanisms that fit the observed profiles, but the simplest is one is where a single ionizable group is present on enzyme–NAD+ and both unprotonated and protonated forms can react. (The sorbitol substrate does not ionize in the pL range studied.)

Results of our pH profile analysis for slSDH in 1H2O (Table 2) agree with earlier findings of Lindstad and McKinley-McKee [17]. It was shown by these authors that the kcat of sorbitol oxidation by slSDH was limited by the dissociation of NADH over the pH range 5.2–9.9 [17]. The pH profile for the rate constant of NADH release was sigmoidal with an apparent pK of 7.45, which we calculate from the two pK values of 7.1 and 7.7, given in [17], as pK=(pK1+pK2)/2. From fits of the pH profile of kcat with Eqn (1), we obtained a nearly identical pK of 7.10±0.15. The previously reported pH profile for kcat/Ksorbitol displayed a pK of 7.1, also consistent with a pK value of 7.15±0.05 found in the present study. In spite of the similar pK values observed in the pH profiles of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol, there was a much larger decrease in kcat/Ksorbitol (120-fold) than kcat (7.5-fold) on going from the high-pH plateau to the one at low pH.

The pK values for the fall of kcat and kcat/Ksorbitol at low pH were both elevated by ≈+0.2 pH units in 2H2O solvent. The observed solvent isotope effect on the kinetically determined pK was lower than expected (ΔpK≈+0.48) if the observed pH-dependence of the enzyme was due to the ionization of a group such as imidazole, carboxy or amino [26]. The comparison of pL profiles in 1H2O and 2H2O may thus assist in the assignment of the apparent pK values to groups, as follows.

For slSDH, the H2O/hydroxy ligand to Zn2+ and a histidine residue were considered to be candidate groups whose ionization could determine the pH-rate profile of the enzyme [17]. The present results support the Zn2+-bound water because the ΔpK for it in 2H2O is supposedly smaller than +0.48. Quinn and Sutton [26,27] report that certain hydrated metal ions such as Fe3+, Gd3+ and La3+ have ΔpK values of ≤+0.3. Likewise, the ΔpK of Co2+-water in carbonic anhydrase appears to be also small [28]. (However, the kinetically determined ΔpK for carbonic anhydrase was ≈+0.5 [29]). With regard to Zn2+-water, Welsh et al. [30] reported that pL-dependencies of kcat for NAD+-dependent oxidation of p-methoxybenzyl alcohol by yeast ADH displayed a ΔpK (=8.35−8.14=+0.21) in 2H2O. They suggested that the small ΔpK could be due to the hydrated metal ion. Note that because catalysis is rate-limiting in the reaction of the yeast enzyme, a comparison of pL profiles of kcat for yeast ADH and kcat/Ksorbitol for slSDH is meaningful. Northrop and Choi [31] showed that the deuterium fractionation factor, Φ, of Zn2+-H2O for enzyme–NAD+ of yeast ADH is approximately 0.56. (Φ is an isotope exchange equilibrium constant [26]). Welsh et al. [30] described that the effect of solvent deuteration on the pK of a protonic species BH can be expressed by the relation ΔpK=log [Φ(BH)/Φ(H3O+)]. Because Φ(H3O+)=0.33 [26], we can estimate that ΔpK for Zn2+-OH2 is +0.23 (=log 0.56/0.33). However, in spite of the seemingly excellent agreement between the calculated ΔpK of Zn2+-OH2 and the kinetically determined ΔpK for slSDH–NAD+ in 2H2O, it must be emphasized that the possible kinetic complexity of kcat/Ksorbitol and the hydrogen-bonded system through which Zn2+-water is linked with protein residues (see Figure 1) make the assignment of apparent pK to group uncertain. Solvent isotope effect studies of horse liver ADH provide a note of caution because unlike the yeast enzyme, ΔpK values for the decrease in rate in pL profiles of kcat and kcat/K for NAD+-dependent oxidation of cyclohexanol at high pL were +1.39±0.21 [32].

pH profiles of GmXDH were similar to those of slSDH. The apparent pK describing the decrease of kcat/Ksorbitol in 1H2O and 2H2O solvent was 7.4±0.1 and 7.6±0.1 respectively. Asymptote levels of kcat/Ksorbitol at high and low pH differed by a factor of 372. The pH-dependence of kcat/Ksorbitol for E154C was clearly distinguished from that for the wild-type, showing an upshift in pK by +1.7 pH units to a value of 9.1±0.3. In 2H2O, the pK was 9.3±0.2, hence again a ΔpK (=+0.2) that was significantly smaller than +0.48. The pH profile of the mutant did not decrease to an asymptote level at low pH, suggesting that unlike the wild-type, the protonated form of E154C does not react. Considering the ΔpK of +0.2 in 2H2O solvent, the observable pK values of 7.4±0.1 and 9.1±0.3 in the NAD+ complexes of wild-type and E154C forms of GmXDH respectively are tentatively assigned to a Zn2+-bound water. Mutation of Glu154 did not abolish the pH-dependence because Zn2+-water is still expected to be present in E154C. However, the carboxylate side chain of the glutamic acid residue could facilitate deprotonation of Zn2+-water through a proton relay or hydrogen bonding, whereas Cys154, due to the smaller size and the higher pK of its side chain, would not be able to fulfil the analogous function.

Interpretation of primary deuterium and solvent KIEs

At the optimum pH of 9.0, primary deuterium KIEs on kinetic parameters for NAD+-dependent oxidation of sorbitol by GmXDH and slSDH were small or not significantly different from unity. This result implies that with both enzymes, hydride transfer was not rate-limiting for the overall reaction (Dkcat) as well as for the catalytic cascade (Dkcat/Ksorbitol) which includes all steps from sorbitol binding to enzyme–NAD+ up to the dissociation of fructose from enzyme–NADH. Release of NADH was probably the slowest step in both enzymatic reactions under kcat conditions, consistent with previous suggestions for the kinetic mechanism of slSDH [16] and GmXDH [15,18].

The KIE on kcat/Ksorbitol for E154C at pH 9.0 was 2.4±0.2, indicating that the chemical step of hydride transfer had become partly rate-limiting for the relevant sequence of reaction steps as a consequence of the site-directed replacement. However, the differences in Dkcat/Ksorbitol for E154C and wild-type at pH 9.0 appear to reflect solely the altered pH-dependence in the mutant. (Dkcat/Ksorbitol) values are similar at the pK of the wild-type enzyme-catalysed reaction (pH 7.5) and at the pK of the E154C-catalysed reaction (pH 9.0).

At pL 9.0, values of D2Okcat (where D2O indicates the solvent KIE) for slSDH and wild-type GmXDH were significantly greater than unity. KiNADH for slSDH determined under the same pL conditions also showed a sizable solvent KIE, and D2OKiNADH≈D2Okcat. The net rate of NADH release (k'NADH) is thought to control kcat of slSDH ([17] and the present study) and contributes to the value of KiNADH. The results therefore suggest that k'NADH is sensitive to solvent deuteration. For slSDH and wild-type GmXDH at pL 9.0, there was a much larger solvent KIE on kcat/Ksorbitol than on kcat/KNAD+, indicating that proton transfers within the steps of kcat/Ksorbitol could be partly rate-limiting. Under conditions where kcat/Ksorbitol did not show a pL-dependence, values of D2Okcat/Ksorbitol for wild-type and E154C forms of GmXDH were almost identical, suggesting that Glu154 is not directly involved in catalytic proton transfer. If it were, a Glu→Cys substitution would arguably make the proton transfer more rate-limiting, detectable as a significant increase in D2Okcat/Ksorbitol for E154C in comparison with wild-type. We note that the thiol group of cysteine has a fractionation factor in 2H2O of ≈0.5 [21], but involvement of the side chain of Cys154 as a protonic site in the active centre of E154C at pL 10.0 is not probable. The results of the KIE studies suggest that Glu154 participates in, but is not essential for hydrogen transfer in the catalytic reaction of GmXDH.

Hydrogen transfer in the catalytic mechanism, and proposed participation of Glu154

Multiple turnover stopped-flow kinetic experiments for sorbitol oxidation by slSDH detected a pre-steady state burst of formation of NADH which corresponded to ≈90% of the enzyme present. This observation requires that there be a slow step after hydride transfer to NAD+ and is fully consistent with evidence from steady-state kinetics reported in the present study and by others [17]. Analysis of the kinetic transient also showed that proton transfers during the reduction of enzyme-bound NAD+ are not rapid equilibrium processes. Their rate is comparable with that of hydride transfer to NAD+, and relative estimation of the corresponding kobs values reveals that proton loss appears to be slightly faster than coenzyme reduction, suggesting that proton dissociation from Zn2+-bound sorbitol could precede the transfer of hydride ion from alcohol to NAD+. The proposed timing of hydrogen transfer steps involved in the chemical oxidation of alcohol substrate by slSDH may thus be very similar to that of liver ADH [33].

Analysis of the stopped-flow progress curves in Figure 3 also revealed that two protons are lost per NADH produced in the pre-steady state. Various steps of the mechanism of slSDH are known to be pH-dependent [17], and a reasonable explanation for the observed proton stoichiometry, consistent with proton release kinetics and in agreement with recent results for liver ADH [34,35], is that formation of the reactive ternary complex is kinetically coupled with deprotonation of the slSDH–NAD+ complex. The weak pH-dependence of kcat for slSDH and GmXDH is in agreement with this notion.

Rapid proton release may be facilitated by a catalytic base acting through a proton-relay system. Pauly et al. [5] have proposed a mechanism of human SDH in which Zn2+-bound water functions as a base, abstracting a proton from the reactive 2-hydroxy group of sorbitol. Results of our pL-dependence studies support a catalytic base function of Zn2+-water. The side chains of Glu70 and Glu155 which were both hydrogen-bonded with Zn2+-water in a model of the ternary complex [5] could participate in a novel type of proton-relay system that connects Glu70 with aqueous solvent, as shown in Figure 4 and discussed below. The suggested role of Glu154 (Glu155 in human SDH) in the catalytic mechanism of PDH enzymes is summarized in Scheme 1.

Figure 4. Alternative proton shuttle pathways for SDH/XDH.

The structure of human liver SDH is shown (PDB: 1PL6) [5]. Hydrogen-bonded networks connecting the active site with bulk water are indicated with arrows. Black and grey dashed lines indicate co-ordination to Zn2+ and hydrogen bonding respectively.

Scheme 1. Proposed participation of Glu154 in the catalytic mechanism of SDH/XDH.

At the optimum pH for sorbitol oxidation, Zn2+-water is deprotonated in the enzyme–NAD+ complex and hydrogen bonds with the negatively charged side chain of Glu154 (Scheme 1A). When sorbitol binds, the carboxylate of Glu154 forms another hydrogen bond with the substrate C1 hydroxy group, which probably helps in positioning the reactive C2 alcohol of the substrate and the catalytic groups on the enzyme, in particular Zn2+ and the hydroxy group co-ordinated with it, for a reaction to take place. Substrate binding displaces Glu69 as a Zn2+ ligand such that the side chain of it can now substitute the side chain of Glu154 in forming a hydrogen bond with Zn2+-OH (Scheme 1B). Significantly, interactions provided by the side chain of Glu69 establish a proton-relay through which the hydroxy group of Zn2+-bound alcohol is associated with bulk water (compare with Figure 4; Glu70 in human SDH). Below the pK of about 7.2–7.4 in enzyme–NAD+, Zn2+-water is protonated, causing a large decrease in activity in both wild-type and mutant enzymes. However, loss of activity is only partial in wild-type, whereas it is complete in the E154C mutant. We would like to suggest that the side chain of Glu154 serves in partially restoring the catalytic base function of Zn2+-OH (together with Glu69) by partly taking up a proton from Zn2+-OH2, as indicated in Scheme 1(C). Note that partial negative charge remaining on the H2O/hydroxy ligand co-ordinating to Zn2+ might also confer electrostatic stabilization to the positively charged nicotinamide ring of NAD+ in a position suitable for hydride transfer. Now, if Glu154 becomes partly protonated (Scheme 1C), its ability to form a charged hydrogen bond with the C1 hydroxy group of sorbitol will be lost and, consequently, apparent binding of sorbitol will be weakened substantially, as is observed at low pH. Due to its smaller size, the side chain of Cys154 is probably too far away from Zn2+-OH2 to function in an analogous proton relay. In addition, even if it were brought through a protein conformational change into a position suitable for proton uptake from Zn2+-OH2, it would probably be present in its protonated form and thus inactive below the observed pK of enzyme–NAD+.

Scheme 1 is subject to the caveat that residues of the hydrogen-bonded system in liver ADH, Ser48 and His51, through which the hydroxy group of Zn2+-bound alcohol is connected via the 2′-hydroxy group of the nicotinamide ribose with bulk water, are conserved in the sequence of human SDH at positions 46 and 49 (Figure 4), and at homologous positions in slSDH and GmXDH sequences. However, a recent study of MDR-type glucose dehydrogenase (from Sulfolobus solfataricus) supports a role of Glu67 in facilitating proton abstraction from substrate to Zn2+-OH and passing on the proton to solvent [36].

Online data

Acknowledgments

Financial support from the Austrian Science Fund (FWF projects P15208 and P18275 to B. N.) is gratefully acknowledged. Veronika Milocco is thanked for expert technical assistance.

References

- 1.Riveros-Rosas H., Julian-Sanchez A., Villalobos-Molina R., Pardo J. P., Pina E. Diversity, taxonomy and evolution of medium-chain dehydrogenase/reductase superfamily. Eur. J. Biochem. 2003;270:3309–3334. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03704.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Persson B., Zigler J. S., Jr, Jörnvall H. A super-family of medium-chain dehydrogenases/reductases (MDR). Sub-lines including ζ-crystallin, alcohol and polyol dehydrogenases, quinone oxidoreductase enoyl reductases, VAT-1 and other proteins. Eur. J. Biochem. 1994;226:15–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1994.tb20021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jeffery J., Jörnvall H. Sorbitol dehydrogenase. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1988;61:47–106. doi: 10.1002/9780470123072.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eklund H., Horjales E., Jörnvall H., Bränden C. I., Jeffery J. Molecular aspects of functional differences between alcohol and sorbitol dehydrogenases. Biochemistry. 1985;24:8005–8012. doi: 10.1021/bi00348a025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pauly T. A., Ekstrom J. L., Beebe D. A., Chrunyk B., Cunningham D., Griffor M., Kamath A., Lee S. E., Madura R., McGuire D., et al. X-ray crystallographic and kinetic studies of human sorbitol dehydrogenase. Structure. 2003;11:1071–1085. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(03)00167-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banfield M. J., Salvucci M. E., Baker E. N., Smith C. A. Crystal structure of the NADP(H)-dependent ketose reductase from Bemisia argentifolii at 2.3 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;306:239–250. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Johansson K., El-Ahmad M., Kaiser C., Jörnvall H., Eklund H., Höög J., Ramaswamy S. Crystal structure of sorbitol dehydrogenase. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2001;130–132:351–358. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(00)00260-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Karlsson C., Höög J. O. Zinc coordination in mammalian sorbitol dehydrogenase. Replacement of putative zinc ligands by site-directed mutagenesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;216:103–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18121.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feiters M. C., Jeffery J. Zinc environment in sheep liver sorbitol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1989;28:7257–7262. doi: 10.1021/bi00444a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maret W. Cobalt(II)-substituted class III alcohol and sorbitol dehydrogenases from human liver. Biochemistry. 1989;28:9944–9949. doi: 10.1021/bi00452a011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eklund H., Nordstrom B., Zeppezauer E., Soderlund G., Ohlsson I., Boiwe T., Soderberg B. O., Tapia O., Bränden C. I., Akeson A. Three-dimensional structure of horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase at 2–4 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1976;102:27–59. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90072-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ryde U. On the role of Glu-68 in alcohol dehydrogenase. Protein Sci. 1995;4:1124–1132. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560040611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindstad R. I., Koll P., McKinley-McKee J. S. Substrate specificity of sheep liver sorbitol dehydrogenase. Biochem. J. 1998;330:479–487. doi: 10.1042/bj3300479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LeBrun L. A., Park D. H., Ramaswamy S., Plapp B. V. Participation of histidine-51 in catalysis by horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 2004;43:3014–3026. doi: 10.1021/bi036103m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lunzer R., Mamnun Y., Haltrich D., Kulbe K. D., Nidetzky B. Structural and functional properties of a yeast xylitol dehydrogenase, a Zn2+-containing metalloenzyme similar to medium-chain sorbitol dehydrogenases. Biochem. J. 1998;336:91–99. doi: 10.1042/bj3360091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindstad R. I., Hermansen L. F., McKinley-McKee J. S. The kinetic mechanism of sheep liver sorbitol dehydrogenase. Eur. J. Biochem. 1992;210:641–647. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb17465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lindstad R. I., McKinley-McKee J. S. Effect of pH on sheep liver sorbitol dehydrogenase steady-state kinetics. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;233:891–898. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1995.891_3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nidetzky B., Helmer H., Klimacek M., Lunzer R., Mayer G. Characterization of recombinant xylitol dehydrogenase from Galactocandida mastotermitis expressed in Escherichia coli. Chem. Biol. Interact. 2003;143–144:533–542. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(02)00215-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ho S. N., Hunt H. D., Horton R. M., Pullen J. K., Pease L. R. Site-directed mutagenesis by overlap extension using the polymerase chain reaction. Gene. 1989;77:51–59. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(89)90358-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Habenicht A., Motejadded H., Kiess M., Wegerer A., Mattes R. Xylose utilisation: cloning and characterisation of the xylitol dehydrogenase from Galactocandida mastotermitis. Biol. Chem. 1999;380:1405–1411. doi: 10.1515/BC.1999.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schowen K. B., Schowen R. L. Solvent isotope effects of enzyme systems. Methods Enzymol. 1982;87:551–606. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook P. F., Cleland W. W. Mechanistic deductions from isotope effects in multireactant enzyme mechanisms. Biochemistry. 1981;20:1790–1796. doi: 10.1021/bi00510a013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cleland W. W. The use of pH studies to determine chemical mechanisms of enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Methods Enzymol. 1982;87:390–405. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(82)87024-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fersht A. W.H. Freeman and Company; 1999. Structure and mechanism in protein science: a guide to enzyme catalysis and protein folding. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schowen K. B. J. Solvent isotope effects. In: Gandour R. D., Schowen R. L., editors. Transition States of Biochemical Processes. New York: Plenum Press; 1978. pp. 225–283. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn D. M., Sutton L. D. Theoretical basis and mechanistic utility of solvent isotope effects. In: Cook P. F., editor. Enzyme Mechanism from Isotope Effects. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1991. pp. 73–126. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn D. M. Theory and practice of solvent isotope effects. In: Kohen A., Limbach H.-H., editors. Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 995–1018. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kassebaum J. W., Silverman D. N. Hydrogen/deuterium fractionation factors of the aqueous ligand of cobalt in Co(H2O)62+ and Co(II)-substituted carbonic anhydrase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1989;111:2691–2696. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pocker Y., Bjorkquist D. W. Comparative studies of bovine carbonic anhydrase in H2O and D2O. Stopped-flow studies of the kinetics of interconversion of CO2 and HCO3−. Biochemistry. 1977;16:5698–5707. doi: 10.1021/bi00645a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh K. M., Creighton D. J., Klinman J. P. Transition-state structure in the yeast alcohol dehydrogenase reaction: the magnitude of solvent and α-secondary hydrogen isotope effects. Biochemistry. 1980;19:2005–2016. doi: 10.1021/bi00551a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Northrop D. B., Cho Y. K. Effects of high pressure on solvent isotope effects of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase. Biophys. J. 2000;79:1621–1628. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76412-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Taylor K. B. Solvent isotope effects on the reaction catalyzed by alcohol dehydrogenase from equine liver. Biochemistry. 1983;22:1040–1045. doi: 10.1021/bi00274a007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sekhar V. C., Plapp B. V. Rate constants for a mechanism including intermediates in the interconversion of ternary complexes by horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1990;29:4289–4295. doi: 10.1021/bi00470a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kovaleva E. G., Plapp B. V. Deprotonation of the horse liver alcohol dehydrogenase-NAD+ complex controls formation of the ternary complexes. Biochemistry. 2005;44:12797–12808. doi: 10.1021/bi050865v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plapp B. V. Catalysis by alcohol dehydrogenases. In: Kohen A., Limbach H.-H., editors. Isotope Effects in Chemistry and Biology. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2006. pp. 811–835. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Milburn C. C., Lamble H. J., Theodossis A., Bull S. D., Hough D. W., Danson M. J., Taylor G. L. The structural basis of substrate promiscuity in glucose dehydrogenase from the hyperthermophilic archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:14796–14804. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601334200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.