Abstract

Background: Current treatment guidelines for Alzheimer's disease (AD) do not reflect more recently collected data on therapeutic outcomes other than cognitive function and memory, and this has led to a limited understanding of the value of drug therapy in AD.

Objectives: To evaluate the need to revise treatment guidelines for AD, to review data that have become available since the publication of current guidelines, and to communicate how existing guidelines and relevant new data can be valuable to the primary care provider who assesses and treats patients with AD.

Data Sources: A MEDLINE search was conducted to identify existing treatment guidelines using the MeSH headings Alzheimer disease–drug therapy AND practice guidelines. The alternative terms treatment guidelines, practice parameter, and practice recommendation were also searched in conjunction with the MeSH term Alzheimer disease–drug therapy. Additionally, MEDLINE was searched using the term dementia and publication type “practice guideline.” All searches were limited to articles published within the last 10 years, in English. A total of 116 articles were identified by these searches. Additional publications were identified by manually searching the reference lists of these articles and of published clinical trials of AD therapies.

Study Selection and Data Extraction: Current AD treatment guidelines and clinical trial results for AD treatment options were extracted, reviewed, and summarized to meet the objectives of this article.

Data Synthesis: Current guidelines support the use of cholinesterase inhibitors in patients with mild to moderate AD. More recent clinical research indicates that cholinesterase inhibitor treatment provides effectiveness across a wide range of dementia severity and multiple symptom domains. These medications also significantly decrease caregiver burden and may lower the risk for nursing home placement.

Conclusions: The expanding literature on AD medications suggests that treatment guidelines need to be reexamined. Recent data emphasize preservation of abilities and delay of adverse outcomes in AD patients rather than short-term improvements in cognitive test scores. Treatment appears to provide the greatest benefit when it is initiated early in the course of the disease and maintained over the long term. Revised treatment guidelines should address newer medications and more recent outcomes considerations, as well as provide guidance on how long to continue and when to discontinue pharmacotherapy for AD.

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a very common condition. It is estimated to affect 6% to 10% of the population over age 65 in the United States. Its prevalence is expected to rise dramatically through the middle of the 21st century. Results from one epidemiologic study projected that there were 4.5 million people in the United States with AD in 2000. An extrapolation of these results that accounts for the continued aging of the population suggested that the number of AD patients in the United States will reach 13.2 million by 2050.1 Not surprisingly, the economic burden of AD is very high. Annual costs for AD and other dementias were estimated at $100 billion in the United States in 1997.2 The overall cost of dementia to U.S. society is therefore similar to that of diabetes mellitus. More recently, it has been estimated that the total direct and indirect costs associated with AD alone are $88.3 billion, with perpatient costs of $91,000 over the course of the illness.3

Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative disorder characterized by abnormalities in multiple brain regions, including the neocortex, entorhinal area, hippocampus, amygdala, nucleus basalis, anterior thalamus, and monoaminergic projections from brainstem nuclei.4,5 The neuropathologic changes characteristic of AD are progressive, and their magnitude correlates with clinical disease severity. Involvement of the cholinergic system in AD was initially suggested by the postmortem observation of substantial neocortical deficits in the enzyme responsible for the synthesis of acetylcholine, choline acetyltransferase. Loss of cholinergic neurons is well documented in patients who have died with AD. Acetylcholine plays a key role in learning and memory, and the predictable cholinergic changes observed in patients with AD led to the “cholinergic hypothesis” to explain the symptom pattern of AD. In this model, degeneration of cholinergic neurons in the basal forebrain and the associated loss of cholinergic neurotransmission in the cerebral cortex, especially in the hippocampus, contributes significantly to the deterioration in cognitive function seen in patients with AD.6–8 The focus on hippocampal acetylcholine input in the cholinergic hypothesis may account for the historical bias toward memory improvement as the desired outcome from AD therapeutics.

Excessive glutamate levels in the cerebral cortex of AD patients have also been hypothesized to contribute to learning and memory deficits in AD. Memantine, a moderate-affinity N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor antagonist, is postulated to counteract this effect.9 Memantine has demonstrated efficacy in moderate to severe AD, but appears to have less consistent effects in mild AD,10 and it has not been approved in the United States for use in patients with mild dementia. The reasons for differences in efficacy by stage are unknown, but may be related to increasing dysfunction in glutamate regulation with more advanced disease.11

As AD progresses, patients experience deterioration across multiple domains, including cognition, function, and behavior, but the specific symptoms vary between patients and between stages. This variability means that treatment targets will need to be revisited and reconsidered across the stages of the disease. Mild AD (often associated with Mini-Mental State Examination [MMSE] scores ≥20) is characterized by forgetfulness and difficulties with activities such as driving, shopping, and hobbies. Patients with mild AD may also be at increased risk for depression. Moderate AD (MMSE score ≈10–19) is reflected by marked memory loss and a requirement for significant assistance with activities of daily living (ADLs). Patients with moderate AD may also exhibit wandering, insomnia, and delusions. Severe AD (MMSE score < 10) is characterized by limited language, loss of basic ADLs, agitation, and incontinence.12,13

METHOD

Treatment guidelines were identified via a MEDLINE search using the MeSH headings Alzheimer disease–drug therapy AND practice guidelines. The alternative terms treatment guidelines, practice parameter, and practice recommendation were also searched in conjunction with the MeSH term Alzheimer disease–drug therapy. Additionally, MEDLINE was searched using the term dementia and publication type “practice guideline.” All searches were limited to articles published within the last 10 years, in English. A total of 116 unique articles were identified. The reference lists of articles thus identified were searched manually to identify additional articles of interest.

CURRENT GUIDELINES FOR THE TREATMENT OF PATIENTS WITH ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

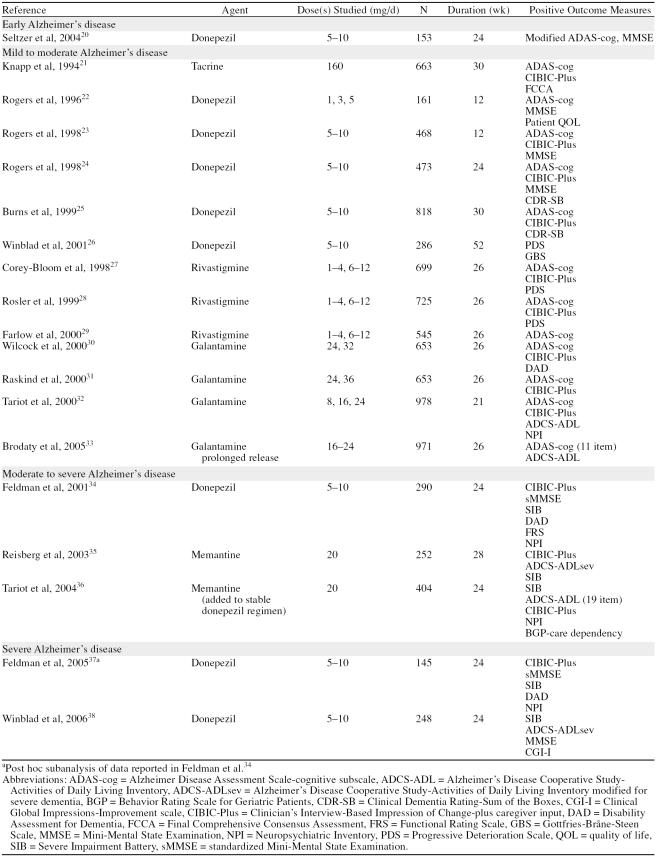

Although treatment guidelines have been published for Japan in 200414 and Italy in 2005,15 the most current clinical guidance for physicians treating patients with AD in the United States was published in 2001, when the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology published 3 practice parameters: early detection of dementia,16 diagnosis of dementia,17 and management of dementia.18 These papers were subsequently abstracted and summarized by the American Geriatrics Society Clinical Practice Committee.19 The primary management question these evidence-based guidelines addressed was whether a treatment “improve[s] outcomes in patients with dementia compared with no treatment.“18 The data available at that time to answer this question were limited—the guidelines cite 6 randomized, controlled clinical trials of cholinesterase inhibitors (ChEIs). Many more such data are available today (Table 1), and other controlled studies have been published using a variety of outcome measures and trial designs to evaluate important aspects of AD treatment beyond standardized efficacy assessments. The purpose of this article is to review these studies and highlight clinical data that are important to providing the best possible treatment for patients with AD in primary care.

Table 1.

Positive Placebo-Controlled Studies of Treatment Options for Alzheimer's Disease

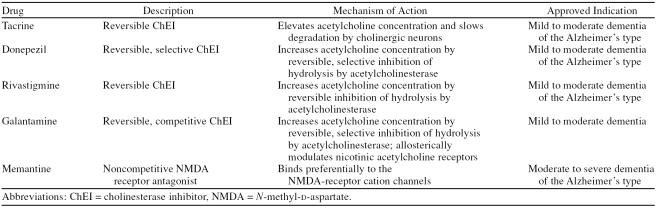

THERAPEUTIC OPTIONS FOR ALZHEIMER'S DISEASE

Cholinesterase inhibitors have been the cornerstone of treatment for patients with AD for over a decade.18,39 Four drugs in this class, donepezil, galantamine, rivastig-mine, and tacrine, are approved for the treatment of mild to moderate AD, and they are recommended by the American Academy of Neurology practice parameter18 as standard of care for treatment of patients with this condition (Table 2). Tacrine was approved for the treatment of AD in 1993, but is now rarely used because of a difficult dosing regimen, poor tolerability, and significant hepatotoxicity. Donepezil was approved for treatment of mild to moderate AD in 1996, rivastigmine was approved in 2000, and galantamine was approved in 2001. Memantine, an NMDA receptor antagonist, was approved for the treatment of moderate to severe AD in 2003 (Table 2). Memantine has also been studied as adjunctive therapy in patients with moderate to severe AD who were being treated with donepezil.36

Table 2.

Treatment Options for Alzheimer's Disease

The ChEIs have repeatedly shown sustained, clinically meaningful benefit in double-blind, placebo-controlled trials.40 Review of their effectiveness in comparison with placebo suggests that the more recently developed ChEIs (rivastigmine, galantamine) have no greater clinical benefit than donepezil. No adequately controlled long-term head-to-head trials have been reported. Memantine has shown clinical benefit in more advanced disease35,36,41; these studies were published subsequent to the most recent guidelines. Recently, the U.K. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence released a guidance statement42 based on a combination of clinical and economic analyses stating that the ChEIs are appropriate for treatment of moderate-stage AD. This overturned their preliminary opinion that current treatment options offer no clinical benefits—an opinion hotly refuted by many physicians and patient/caregiver advocates. Nonetheless, many physicians still do not believe that there are meaningful treatment options for patients with AD.

REDEFINING TREATMENT SUCCESS

There are currently no means for reversing the pathologic processes of AD. Therefore, the specific goals of therapy are to preserve cognitive and functional ability, minimize behavioral disturbances, and slow disease progression,39 with maintenance of the patient's (and care-giver's) quality of life. Much of the criticism of the ChEIs can be attributed to biased or uninformed perceptions of what therapy should be accomplishing rather than an absence of effect in well-conducted clinical trials. The impact of ChEI treatment has most often been measured in terms of effects of these medications on cognition and memory; however, patients and caregivers view the benefits of these treatments much more broadly than most physicians. Analysis of results from a trial of donepezil in 108 patients with mild to moderate AD indicated that patients and caregivers set different treatment goals than physicians. Patients and caregivers tended to identify solutions to specific problems (e.g., reduction in repetitive questions, decreased need for lists and routines) as targets for therapy while physicians grouped many distinct problems under a single treatment goal of improved memory. In addition, patients and their caregivers set more goals than physicians did with respect to leisure, social interaction, behavior, and function.43

It is becoming increasingly recognized that efficacy measures used to evaluate responses to ChEIs do not capture the full benefit of these treatments. The instruments used in clinical trials are required for regulatory approval of the drugs. They are based on historical preconceptions of what is important to study rather than on meeting genuine patient needs, and they do not translate well to clinical practice settings. Results from a survey of physicians who care for patients with AD indicated that physicians recognize benefits of therapy (e.g., cognitive activation, attention, ability to carry out leisure activities, reduced requirement for repetition) that are not captured by instruments currently used to assess outcomes in clinical trials.44 Capturing these effects of treatment is important for comparison of therapies as well as for their potential to increase our understanding of the physiologic basis of the symptoms in AD.44 Outcomes meaningful to patients and families, such as quality of life, preservation of personality and function, and contributions to family life, are exceptionally difficult to measure because they are so individual-specific. Therefore, it seems most reasonable to weight functional abilities, behavioral problems, caregiver burden, and health care resource utilization more heavily in evaluation of therapies for AD.

Although current guidelines discuss functional and behavioral outcomes, increased emphasis should be placed on the ability of treatments to slow the progressive changes in all of these measures.45 A response to treatment in patients with this condition may be best defined as long-term stabilization or less than expected decline rather than a transient improvement from baseline.45 As the American Academy of Neurology guidelines point out, global improvements in cognition, function, and behavior were detectable, indicating that the changes detected on standardized assessments were clinically meaningful.18 Therefore, global assessments such as the Clinician's Interview-Based Impression of Change-plus caregiver input (CIBIC-Plus) and Clinician's Global Impression of Change may be more clinically translatable outcome measures than cognitive scales. Additionally, research using important practical measures (for example, time to nursing home placement, functional decline, or other defined outcome) should be incorporated into the guidelines and considered by primary care providers when making treatment decisions.

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING CURRENT GUIDELINES

The ChEIs have a broad base of evidence from randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials that supports their utility across a wide range of clinically meaningful outcomes. The “regulatory”-type studies are summarized in Table 1. In addition to effects on cognition, these drugs have demonstrated significant effects on measures of behavior, ADLs, and global patient function. Some positive effects have been seen on measures of cognition, ADLs, and global function in severe AD with memantine,35,36,41 but because it is a newer agent, fewer outcomes have been studied.

There have been 3 recent meta-analyses of clinical results obtained with ChEIs in patients with AD. Trinh and colleagues46 evaluated 29 parallel-group or crossover, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials of outpatients with mild to moderate AD who were treated for ≥1 month. Their analysis indicated that ChEI treatment had statistically significant modest benefits with respect to neuropsychiatric and functional outcomes. A second meta-analysis of 16 trials indicated that the placebo-corrected global and cognitive “response” rates were 9% and 10%, respectively, with a placebo-corrected adverse event rate of 8%.47 This analysis indicated that the numbers of patients needed to treat to achieve 1 global response and 1 cognitive response and to cause an adverse event in 1 patient were 12, 10, and 12, respectively.47 However, a global response was defined as improvement on the Clinician's Global Impression of Change, and a cognitive response was defined as an improvement of 4 points or more on the Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale-cognitive subscale. This definition of response does not account for patients who show less than expected decline, another clinically important outcome of treatment. Whitehead and associates48 carried out a meta-analysis of results for donepezil that focused on phase II and III double-blind, placebo-controlled trials up to 24 weeks in duration that were completed by the end of 1999. Cognitive performance and CIBIC-Plus scores were better in patients treated with donepezil than in those receiving placebo (p ≤.001 for both the 5- and 10-mg doses; odds ratio [OR] = 1.77 and 1.90, respectively). Results obtained with 10 mg/day of donepezil were significantly superior to those with the 5-mg/day dose (p = .005).48

A more comprehensive, global view of AD treatment should focus on delaying outcomes rather than on improving performance on cognitive tests. A good example contrasting these ways of thinking about AD outcomes is the recent investigation of donepezil for amnestic mild cognitive impairment, a condition that has been shown to be associated with high risk for conversion to AD. A 24-week trial designed to demonstrate improvement on a cognitive test, the NYU Paragraph Recall test, failed to detect a significant effect49; however, a 3-year donepezil trial designed to detect differences in the rate of progression from mild cognitive impairment to AD found that treatment with donepezil delayed this transition, at least early in the observation period.50

EVIDENCE SUPPORTING EXPANSION OF CURRENT GUIDELINES

How Long to Treat?

Guidelines published in 2001 did not have the benefit of subsequently published studies with longer duration and patient populations with more advanced AD. As patients being treated for AD continue to progress (at an apparently slower rate than they would without treatment), physicians have heard multiple opinions about the value of maintaining these treatments into more advanced stages of AD. Open-label extension studies of placebo-controlled clinical trials indicate that patients appear to benefit from these treatments for several years.51–58 Sustained benefit has been indicated in studies of up to 5 years' duration.51,58 Studies in patients with moderate to severe and severe AD are summarized in Table 1.

Other outcomes are also important in considering how long to continue treatment. For example, the 3-year risk for placement in a nursing home for patients with dementia has been estimated as 52%.59 Dependencies in ADLs, high cognitive impairment, and the presence of 1 or more difficult behaviors all increase this risk.59 Several studies have shown that persistent long-term treatment with a ChEI significantly decreases the risk for nursing home placement. Results from a cohort of 270 patients (135 taking a ChEI and 135 otherwise matched patients who were not) indicated that active treatment decreased the risk for nursing home placement from 41.5% to 6% over an average of 36.7 months of follow-up (p < .0001).60 An analysis of dementia-related nursing home placement for 671 patients who were treated with donepezil in 1 of 3 randomized, double-blind trials found that donepezil dose and time on treatment were significantly correlated with time to first nursing home placement. Patients who received < 5 mg/day of donepezil or placebo during a double-blind trial and who failed to complete open-label extension studies of 24 to 96 weeks had an average time to institutionalization of 44.7 months. Those who received ≥5 mg/day of donepezil with ≥80% compliance during both double-blind treatment and 24- to 96-week open-label extensions had an average time to nursing home placement of 66.1 months (p < .01).61 In a long-term, double-blind, placebo-controlled study conducted in the United Kingdom, no effect of donepezil on nursing home placement was detected, but low enrollment, methodological issues, and societal differences in health care delivery limit the extent to which these findings can be generalized.62

Most recently, Lopez et al.63 showed that treatment with a ChEI for at least 12 months slows AD progression (OR for MMSE score change ≤2 at 1 year of follow-up = 2.32; p = .001 compared with no treatment) and that this slower progression is associated with significantly decreased risk for nursing home placement over 2 and 3 years of follow-up (1% vs. 16%, p = .001; and 11% vs. 50%, p = .001, respectively). (Most patients in this study who were treated with ChEIs [N = 135] took donepezil [N = 130], but some patients took tacrine [N = 22] or rivastigmine [N = 6]. Some patients switched drugs and therefore took more than 1 ChEI.) A retrospective analysis of a large U.S. medical claims database also supports the effectiveness of ChEI treatment in decreasing the risk for nursing home placement. Over a follow-up period of 27 months, 3.7% of 1181 patients who received rivastig-mine, 4.4% of 3864 patients treated with donepezil, and 11.0% of 517 patients who did not receive a ChEI were placed in nursing homes.64

Taken together, these studies indicate that long-term use of ChEIs may help AD patients live longer in community settings, with associated personal, social, and economic benefits. Similar data on memantine are not currently available. Recent evidence65 from imaging studies suggests a possible anatomic basis for the slowed progression reported by Lopez and colleagues. In a 24-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, patients who received donepezil (N = 34) had a mean total hip-pocampal volume loss of 0.4%, compared with 8.2% in patients who received placebo (N = 33; p < .01). Levels of N-acetylaspartate, a marker of neuronal viability and/or function, were also increased with donepezil treatment in some brain regions.65 A prospective cohort study66 also found that donepezil decreased the rate of hippocampal atrophy compared with untreated control subjects (3.82%, N = 54 vs. 5.04%, N = 93). This effect was statistically significant in an analysis of covariance model controlling for age, sex, disease duration, education, MRI interval, APOE genotype, and baseline cognitive assessment scores.66 Furthermore, a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study67 in 28 patients found that donepezil treatment stabilized glucose metabolism in some brain regions. The treatment difference at week 24 was significant for average glucose metabolism in the striatal axial slice (−0.5% vs. –10.4%; p = .014) and for regional glucose metabolism in predetermined regions of interest in the right parietal lobe (6.8% vs. –5.3%; p = .030), left temporal lobe (1.7% vs. –7.6%; p = .045), and right and left frontal lobes (2.8% vs. –9.7%, p = .016 and 0.4% vs. –8.3%, p = .042, respectively).67

Preserving ADL Function

Current guidelines recognize that preventing or delaying further loss of ADL function is an important goal of AD therapy and that ChEIs help to maintain ADL function.18 Although it is unrealistic to expect most patients to regain ADLs they have lost, it is reasonable to expect slowed or delayed functional decline. Significant preservation of ADL function compared with placebo has been shown for donepezil,25,26,34 galantamine,30,32,33,68,69 and rivastigmine.27,28,70,71 Memantine has also demonstrated benefits in ADLs.35,36,41 In a year-long study, patients taking donepezil were shown to retain levels of ADL function significantly longer than patients given placebo (a 5-month average delay to functional decline).72

Reducing Problem Behaviors

Personality changes, mood disturbances, and even psychosis are frequently observed in patients with AD and are associated with more rapid cognitive and functional declines.73 Difficult behaviors increase the risk of nursing home placement.59 Problem behaviors in AD have also been associated with increased time and stress burden,74,75 higher rates of depression,76 and reduced employment77 among caregivers of AD patients. Patients treated with ChEIs and/or memantine may evidence behavioral benefits as reduced severity of existing behavioral disturbances and a lower incidence of new behavioral symptoms.

Studies of donepezil and galantamine using the Neuropsychiatric Inventory (NPI) have shown short-term behavioral improvement or stabilization.32,34,78 Donepezil has been shown to reduce the severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms in 134 patients with mild to moderate AD and marked neuropsychiatric symptoms at baseline (NPI score of at least 11 points). These patients were treated on an open-label basis for 12 weeks (6 weeks with 5 mg/day of donepezil followed by 10 mg/day for an additional 6 weeks). During the open-label phase, total scores were significantly reduced from baseline (mean score, 15.2 at week 12 vs. 25.4 at baseline; p < .0001). All domains of the NPI with the exception of elation were also significantly improved from baseline during this phase of treatment (all p < .05). The patients were then randomly assigned to either continue donepezil treatment or switch to placebo. The patients who continued on donepezil treatment for 12 weeks experienced significant improvements in NPI (treatment difference, 6.2 points; p = .02) compared with those switched to placebo, who experienced significant worsening.79 Galantamine stabilized NPI scores over 5 months and reduced the incidence of new problematic behaviors.80 Rivastigmine may improve or prevent disruptive behavioral symptoms and may reduce the need for concomitant psychotropic medication.81 A trial of memantine monotherapy in moderate to severe AD showed no significant difference from placebo-treated patients on the NPI over 28 weeks.35 In another trial, adding memantine to a stable donepezil regimen in patients with moderate to severe AD resulted in significantly less behavioral disturbance than in patients treated with donepezil only.36

Reducing Caregiver Burden

Caregivers experience significant stress, which may affect their own health.82 Results from several studies have demonstrated that treatment with a ChEI decreases AD caregiver burden. Results from a 24-week double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 290 patients with moderate to severe AD (baseline standardized MMSE score, 5–17) indicated that donepezil treatment significantly reduced caregiver time spent assisting patients with basic and instrumental ADLs (−52.4 minutes/day, p < .005).83 Similarly, in a year-long study, caregivers of donepezil-treated patients spent less time assisting patients with ADLs than caregivers of patients in the placebo group.84 Data from a small study of rivastigmine (N = 43) were used to estimate that rivastigmine treatment saved caregiver time—up to 690 hours over 2 years—that would have been spent assisting with ADLs.85 These studies indicate that AD therapy is associated with the important benefit of reduced caregiver stress.

SUMMARY

ChEI treatment has significant and meaningful direct benefit for AD patients, decreases the risk for nursing home placement, and reduces caregiver burden. While current guidelines support the use of ChEIs in patients with mild to moderate AD, results from more recent clinical trials indicate that ChEI treatment may also be effective across all stages of AD, as well as for mild cognitive impairment. Nevertheless, these drugs are still underutilized, partly because physicians underestimate the value of treatment to patients and caregivers. Physicians should consider the goals voiced by patients and their caregivers when evaluating the effectiveness of treatment.

Current treatment guidelines for use of ChEIs need to be revised and expanded. ChEI treatment is effective in patients across the spectrum of AD severity, but it has often been viewed in the acute therapeutic model: a drug is given and the patient should improve. In this model, failure to improve from baseline represents failure of therapy. However, the impact of ChEI therapy on disease progression in patients with, and at risk for, AD suggests that ChEIs should be viewed more like antihypertensives and lipid-lowering agents for decreasing the risk for cardiovascular events. If maintaining a person at the highest possible level of function is the goal of treatment, then long-term therapy with these agents should be most beneficial when initiated early in the course of the disease and maintained with good patient compliance over the long term. As new guidelines for the treatment of AD are developed, current data strongly support a change in emphasis to consider the utility of ChEIs, not as a treatment approach designed purely to relieve symptoms, but rather as a chronic treatment that reduces the progression and associated burden of a chronic disease.

Drug names: donepezil (Aricept), galantamine (Razadyne), meman-tine (Namenda), rivastigmine (Exelon), tacrine (Cognex).

Footnotes

This review was supported by Pfizer Inc. (New York, N.Y.) and Eisai, Inc. (Teaneck, N.J.). Editorial assistance was provided by PPSI (Stamford, Conn.).

Dr. Geldmacher has received research support from Eisai; has served as a consultant for and is a speaker's bureau member for Eisai, Forest, Pfizer, and Novartis; and has received honoraria from Johnson & Johnson, Eisai, Forest, Pfizer, and Novartis.

REFERENCES CITED

- Hebert LE, Scherr PA, and Bienias JL. et al. Alzheimer disease in the US population: prevalence estimates using the 2000 census. Arch Neurol. 2003 60:1119–1122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirschstein R. Disease-Specific Estimates of Direct and Indirect Costs of Illness and NIH Support. Fiscal Year 2000 Update. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health Web site. Available at: http://www..od.nih.gov/osp/ospp/ecostudies/COIreportweb.htm. Accessed October 31, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom BS, de Pouvourville N, Straus WL.. Cost of illness of Alzheimer's disease: how useful are current estimates? Gerontologist. 2003;43:158–164. doi: 10.1093/geront/43.2.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubenko GS, Moossy J, and Martinez AJ. et al. Neuropathologic and neuro-chemical correlates of psychosis in primary dementia. Arch Neurol. 1991 48:619–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoogendijk WJ, Feenstra MG, and Botterblom MH. et al. Increased activity of surviving locus ceruleus neurons in Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 1999 45:82–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesulam M, Shaw P, and Mash D. et al. Cholinergic nucleus basalis tauopathy emerges early in the aging-MCI-AD continuum. Ann Neurol. 2004 55:815–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry AV Jr, Buccafusco JJ.. The cholinergic hypothesis of age and Alzheimer's disease–related cognitive deficits: recent challenges and their implications for novel drug development. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;306:821–827. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.041616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mufson EJ, Ma SY, and Dills J. et al. Loss of basal forebrain P75(NTR) immunoreactivity in subjects with mild cognitive impairment and Alzheimer's disease. J Comp Neurol. 2002 443:136–153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doraiswamy PM.. Non-cholinergic strategies for treating and preventing Alzheimer's disease. CNS Drugs. 2002;16:811–824. doi: 10.2165/00023210-200216120-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McShane R, Areosa SA, Minakaran N.. Memantine for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003154. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003154.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mishizen-Eberz AJ, Rissman RA, and Carter TL. et al. Biochemical and molecular studies of NMDA receptor subunits NR1/2A/2B in hippocampal subregions throughout progression of Alzheimer's disease pathology. Neurobiology Dis. 2004 15:80–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Boron S, Scanlon JM.. Stage-specific prevalence of behavioral symptoms in Alzheimer's disease in a multi-ethnic community sample. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2000;8:123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward A, Caro JJ, and Kelley H. et al. Describing cognitive decline of patients at the mild or moderate stages of Alzheimer's disease using the Standardized MMSE. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002 14:249–258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura S.. A guideline for the treatment of dementia in Japan. Intern Med. 2004;43:18–29. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.43.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caltagirone C, Bianchetti A, and Di Luca M. et al. Guidelines for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease from the Italian Association of Psychogeriatrics. Drugs Aging. 2005 22suppl 1. 1–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Stevens JC, and Ganguli M. et al. Practice parameter: early detection of dementia: mild cognitive impairment (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 56:1133–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knopman DS, DeKosky ST, and Cummings JL. et al. Practice parameter: diagnosis of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 56:1143–1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doody RS, Stevens JC, and Beck C. et al. Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001 56 1154–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AGS Clinical Practice Committee. Guidelines abstracted from the American Academy of Neurology's Dementia Guidelines for Early Detection, Diagnosis, and Management of Dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:869–873. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2389.2003.51272.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seltzer B, Zolnouni P, and Nunez M. et al. Efficacy of donepezil in early-stage Alzheimer disease: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Arch Neurol. 2004 61:1852–1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knapp MJ, Knopman DS, and Solomon PR. et al. A 30-week randomized controlled trial of high-dose tacrine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. The Tacrine Study Group. JAMA. 1994 271:985–991. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Friedhoff LT. and the Donepezil Study Group. The efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease: results of a US multicentre, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Dementia. 1996;7:293–303. doi: 10.1159/000106895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Doody RS, and Mohs RC. et al. Donepezil improves cognition and global function in Alzheimer disease: a 15-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Donepezil Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1998 158:1021–1031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Farlow MR, and Doody RS. et al. A 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of donepezil in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Donepezil Study Group. Neurology. 1998 50:136–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns A, Rossor M, and Hecker J. et al. The effects of donepezil in Alzheimer's disease: results from a multinational trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1999 10:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Engedal K, and Soininen H. et al. A 1-year, randomized, placebo-controlled study of donepezil in patients with mild to moderate AD. Neurology. 2001 57:489–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corey-Bloom J, Anand R, and Veach J. et al. A randomized trial evaluating the efficacy and safety of ENA 713 (rivastigmine tartrate), a new acetyl-cholinesterase inhibitor, in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol. 1998 1:55–65. [Google Scholar]

- Rosler M, Anand R, and Cicin-Sain A. et al. Efficacy and safety of rivastig-mine in patients with Alzheimer's disease: international randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1999 318:633–638.Correction 2001;322:1456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farlow M, Anand R, and Messina J Jr. et al. A 52-week study of the efficacy of rivastigmine in patients with mild to moderately severe Alzheimer's disease. Eur Neurol. 2000 44:236–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilcock GK, Lilienfeld S, and Gaens E. Efficacy and safety of galantamine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: multicentre randomised controlled trial. Galantamine International-1 Study Group. BMJ. 2000 321:1445–1449.Correction 2001;322:405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, and Wessel T. et al. Galantamine in AD: a 6-month randomized, placebo-controlled trial with a 6-month extension. The Galantamine USA-1 Study Group. Neurology. 2000 54:2261–2268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Solomon PR, and Morris JC. et al. A 5-month, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of galantamine in AD. Neurology. 2000 54:2269–2276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodaty H, Corey-Bloom J, and Potocnik FC. et al. Galantamine prolonged-release formulation in the treatment of mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005 20:120–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, and Hecker J. et al. A 24-week, randomized, double-blind study of donepezil in moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 2001 57:613–620.Correction 2001;57:2153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Doody R, and Stoffler A. et al. Memantine in moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med. 2003 348:1333–1341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tariot PN, Farlow MR, and Grossberg GT. et al. Memantine treatment in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer disease already receiving donepezil: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004 291:317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, and Hecker J. et al. Efficacy and safety of donepezil in patients with more severe Alzheimer's disease: a subgroup analysis from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Donepezil MSAD Study Investigators Group. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2005 20:559–569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Kilander L, and Eriksson S. et al. Donepezil in patients with severe Alzheimer's disease: double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Severe Alzheimer's Disease Study Group. Lancet. 2006 367:1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher DS. Alzheimer's disease: current pharmacotherapy in the context of patient and family needs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 51suppl 5. S289–S295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher DS.. Donepezil (Aricept) for treatment of Alzheimer's disease and other dementing conditions. Expert Rev Neurother. 2004;4:5–16. doi: 10.1586/14737175.4.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Poritis N.. Memantine in severe dementia: results of the 9M-Best Study (benefit and efficacy in severely demented patients during treatment with memantine) Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14:135–146. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1166(199902)14:2<135::aid-gps906>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nm N. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Appraisal Consultation Document: Alzheimer's disease—donepezil, rivastigmine, galantamine and memantine (review). NICE Web site. Available at: http://www.nice.org.uk/page.aspx?o=245908. Accessed January 30, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Graham JE, Fay S.. Goal setting and attainment in Alzheimer's disease patients treated with donepezil. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:500–507. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.73.5.500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Black SE, and Robillard A. et al. Potential treatment effects of donepezil not detected in Alzheimer's disease clinical trials: a physician survey. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004 19:954–960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winblad B, Brodaty H, and Gauthier S. et al. Pharmacotherapy of Alzheimer's disease: is there a need to redefine treatment success? Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001 16:653–666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trinh N-H, Hoblyn J, and Mohanty S. et al. Efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms and functional impairment in Alzheimer disease: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003 289:210–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lanctot KL, Herrmann N, and Yau KJF. et al. Efficacy and safety of cholinesterase inhibitors in Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. CMAJ. 2003 169:557–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead A, Perdomo C, and Pratt RD. et al. Donepezil for the symptomatic treatment of patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis of individual patient data from randomised controlled trials. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004 19:624–633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloway S, Ferris S, and Kluger A. et al. Efficacy of donepezil in mild cognitive impairment: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Neurology. 2004 63:651–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen RC, Thomas RG, and Grundman M. et al. Vitamin E and donepezil for the treatment of mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2005 352:2379–2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogers SL, Doody RS, and Pratt RD. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of donepezil in the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: final analysis of a US multicentre open-label study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2000 10:195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doraiswamy PM, Krishnan KR, and Anand R. et al. Long-term effects of rivastigmine in moderately severe Alzheimer's disease: does early initiation of therapy offer sustained benefits? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2002 26:705–712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raskind MA, Peskind ER, and Truyen L. et al. The cognitive benefits of galantamine are sustained for at least 36 months: a long-term extension trial. Arch Neurol. 2004 61:252–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirttila T, Wilcock G, and Truyen L. et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of galantamine in patients with mild-to-moderate Alzheimer's disease: multicenter trial. Eur J Neurol. 2004 11:734–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyketsos CG, Reichman WE, and Kershaw P. et al. Long-term outcomes of galantamine treatment in patients with Alzheimer disease. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004 12:473–482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossberg G, Irwin P, and Satlin A. et al. Rivastigmine in Alzheimer disease: efficacy over two years. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2004 12:420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisberg B, Doody R, and Stoffler A. et al. A 24-week open-label extension study of memantine in moderate to severe Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2006 63:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small GW, Kaufer D, and Mendiondo MS. et al. Cognitive performance in Alzheimer's disease patients receiving rivastigmine for up to 5 years. Int J Clin Pract. 2005 59:473–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaffe K, Fox P, and Newcomer R. et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics and nursing home placement in patients with dementia. JAMA. 2002 287:2090–2097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, and Wisniewski S. et al. Cholinesterase inhibitor treatment alters the natural history of Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002 72:310–314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher DS, Provenzano G, and McRae T. et al. Donepezil is associated with delayed nursing home placement in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 51:937–944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney C, Farrell D, and Gray R. et al. Long-term donepezil treatment in 565 patients with Alzheimer's disease (AD2000): randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2004 363:2105–2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez OL, Becker JT, and Saxton J. et al. Alteration of a clinically meaningful outcome in the natural history of Alzheimer's disease by cholinesterase inhibition. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005 53:83–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beusterien KM, Thomas SK, and Gause D. et al. Impact of rivastigmine use on the risk of nursing home placement in a US sample. CNS Drugs. 2004 18:1143–1148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishnan KR, Charles HC, and Doraiswamy PM. et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the effects of donepezil on neuronal markers and hippocampal volumes in Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2003 160:2003–2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashimoto M, Kazui H, and Matsumoto K. et al. Does donepezil treatment slow the progression of hippocampal atrophy in patients with Alzheimer's disease? Am J Psychiatry. 2005 162:676–682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tune L, Tiseo PJ, and Ieni J. et al. Donepezil HCl (E2020) maintains functional brain activity in patients with Alzheimer disease: results of a 24-week, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2003 11:169–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galasko D, Kershaw PR, and Schneider L. et al. Galantamine maintains ability to perform activities of daily living in patients with Alzheimer's disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004 52:1070–1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Mintzer J, and Truyen L. et al. Effects of a flexible galantamine dose in Alzheimer's disease: a randomised, controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001 71:589–595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karaman Y, Erdogan F, and Koseoglu E. et al. A 12-month study of the efficacy of rivastigmine in patients with advanced moderate Alzheimer's disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2005 19:51–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider LS, Anand R, and Farlow MR. Systematic review of the efficacy of rivastigmine for patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychopharmacol. 1998 1suppl 1. S26–S34. [Google Scholar]

- Mohs RC, Doody RS, and Morris JC. et al. A 1-year, placebo-controlled preservation of function survival study of donepezil in AD patients. Neurology. 2001 57:481–488.Correction 2001;57:1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung JA, Cummings JL.. Neurobehavioral and neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: characteristics and treatment. Neurol Clin. 2000;18:829–846. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8619(05)70228-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger G, Bernhardt T, and Weimer E. et al. Longitudinal study on the relationship between symptomatology of dementia and levels of subjective burden and depression among family caregivers in memory clinic patients. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol. 2005 18:119–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marvardi M, Mattioli P, and Spazzafumo L. et al. The Caregiver Burden Inventory in evaluating the burden of caregivers of elderly demented patients: results from a multicenter study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2005 17:46–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Newcomer R, and Fox P. et al. Patient and caregiver characteristics associated with depression in caregivers of patients with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2003 18:1006–1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Covinsky KE, Eng C, and Lui LY. et al. Reduced employment in caregivers of frail elders: impact of ethnicity, patient clinical characteristics, and caregiver characteristics. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001 56:M707–M713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gauthier S, Feldman H, and Hecker J. et al. Efficacy of donepezil on behavioral symptoms in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2002 14:389–404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes C, Wilkinson D, and Dean C. et al. The efficacy of donepezil in the treatment of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2004 63:214–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings JL, Schneider L, and Tariot PN. et al. Reduction of behavioral disturbances and caregiver distress by galantamine in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2004 161:532–538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finkel SI.. Effects of rivastigmine on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia in Alzheimer's disease. Clin Ther. 2004;26:980–990. doi: 10.1016/s0149-2918(04)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell CM, Araki SS, Neumann PJ.. The association between caregiver burden and caregiver health-related quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2001;15:129–136. doi: 10.1097/00002093-200107000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman H, Gauthier S, and Hecker J. et al. Efficacy of donepezil on maintenance of activities of daily living in patients with moderate to severe Alzheimer's disease and the effect on caregiver burden. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003 51:737–744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wimo A, Winblad B, and Shah SN. et al. Impact of donepezil treatment for Alzheimer's disease on caregiver time. Curr Med Res Opin. 2004 20:1221–1225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marin D, Amaya K, and Casciano R. et al. Impact of rivastigmine on costs and on time spent in caregiving for families of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2003 15:385–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]