Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) afflicts children, adolescents, and adults. Anxiety disorders, in both children and adults, are among the disorders that most commonly co-occur with ADHD.1–3 The presence of these comorbid disorders complicates accurate diagnoses and appropriate treatment of both the primary and the comorbid disorders. Pharmacotherapy has long been the standard treatment for ADHD; however, a question exists as to whether comorbid anxiety disorders may alter response to ADHD pharmacotherapy. In clinical practice, a high degree of variability exists in the treatment of ADHD, due in part to comorbid anxiety disorders and the wide range of ages affected by ADHD. The purpose of this roundtable discussion was to define just how commonly ADHD and anxiety co-occur, the problems that result from this comorbidity, and how pharmacologic and nonphar-macologic interventions can influence the course of both anxiety disorders and ADHD in children, adolescents, and adults.

Epidemiology of ADHD and Comorbid Anxiety Disorders

Dr. Adler: Our first topic is the epidemiology of anxiety disorders and ADHD, not only the prevalence of the disorders in different age groups but also the types of disorders observed.

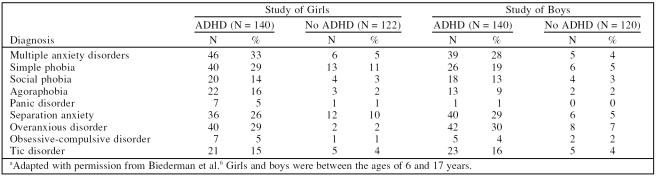

Dr. Barkley: The Multimodal Treatment Study of Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (MTA)2 found a 33.5% prevalence of anxiety disorders. Other studies3–6 have found a similar prevalence of anxiety disorders in children with ADHD; for example, Biederman et al.6 reported a rate of multiple comorbid anxiety disorders of 33% in girls and 28% in boys (Table 1). In this study, children with ADHD were more likely to have anxiety disorders than children who did not have ADHD.

Table 1.

Anxiety Among Girls and Boys With and Without Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD)a

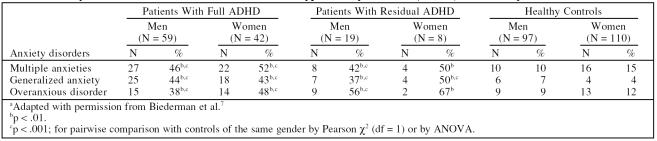

There appears to be an age-related increase in the prevalence of comorbid anxiety. In a study of referred adults whose ADHD persisted from childhood into adulthood, Biederman et al.7 found that more than 40% of men and more than 50% of women with full or residual ADHD had multiple anxiety disorders (Table 2). As with children, the rate of anxiety disorders was greater in adults with ADHD than in healthy controls.

Table 2.

Anxiety in Adult Patients With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and Healthy Controlsa

Dr. Spencer: There has always been controversy regarding whether the prevalence of comorbid disorders is greater in study subjects who are referred than in individuals in the community. However, a review4 showed that in epidemiologic studies, rates of comorbidity in untreated individuals in the community were similar to those of the referred individuals, so the rates were not an artifact of psychiatric referral or self-report.

Dr. Barkley: An individual's diagnoses may change over time. Biederman et al.8 found that children with ADHD and comorbid multiple anxieties at baseline had a significantly increased risk for agoraphobia, social phobia, and separation anxiety 4 years later compared with children with ADHD but no comorbidity at baseline. Peterson et al.9 followed randomly selected children for 8, 10, and 15 years and found that children with ADHD symptoms in adolescence had more symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) in early adulthood than the control individuals, and those with OCD in adolescence had more symptoms of ADHD in adulthood than control individuals.

Dr. Spencer: While many comorbid disorders tend to remain consistent throughout life, some anxiety disorders may take the form of other anxiety disorders later in life, as Dr. Barkley described. Also, within families, anxiety disorders may be expressed differently among individuals.10

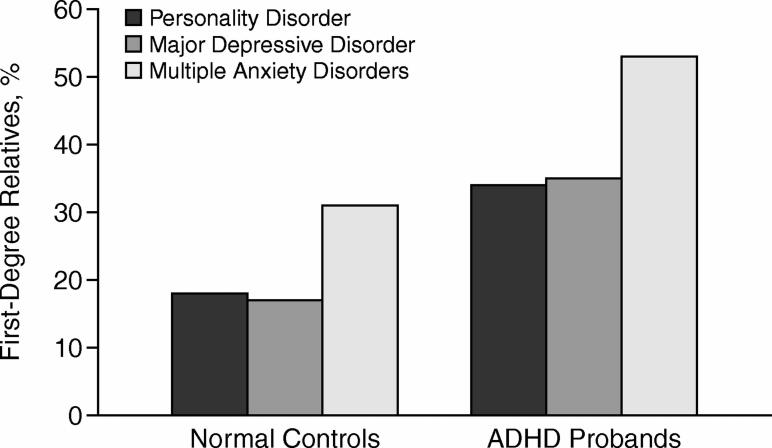

Dr. Barkley: If a patient has an anxiety disorder, one can certainly expect a higher incidence of anxiety disorders within the family than among families of controls (Figure 1).11

Figure 1.

Prevalence of Psychiatric/Mutual Disorders in First-Degree Relatives of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) Probands and Normal Controlsa

Dr. Spencer: The Yale Family Study10 found a relative specificity to genetic risk; children of people with psychiatric disorders tended to have disorders similar to those of their parents. For example, if a person had depression plus panic disorder or agoraphobia, the children of that person were more likely to have depression and an anxiety disorder. If the person had depression but not an anxiety disorder, the child was unlikely to have an anxiety disorder. And if a patient has 1 anxiety disorder, then that patient has a greater risk of developing other anxiety disorders as well.12

Dr. Barkley: McGough et al.13 found that 87% of individuals with ADHD whose children also had ADHD had at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 56% had at least 2 other psychiatric disorders.

Dr. Spencer: In one study14 that my colleagues and I performed, 50% of referred adults with ADHD, 42% of nonreferred adults with ADHD, and 14% of the control group had multiple anxiety disorders.

Dr. Adler: The National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R)15 reported that 47% of adults with ADHD had a comorbid anxiety disorder within the previous 12 months. Therefore, it is not just self-referred adults who exhibit elevated rates of comorbid anxiety disorders, despite the usual theory that the rate of comorbidity is higher in referred populations.

One anxiety disorder seen more often in adults than in children with ADHD is posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The NCS-R study found that 12% of adults with ADHD had comorbid PTSD.

Dr. Spencer: Fewer incidences of PTSD in children than in adults may be an effect of age. A child with ADHD would have to be in a setting that puts him or her at risk to encounter trauma in order to be diagnosed with PTSD.

Dr. Adler: The incidence of PTSD may phenomenologically differ between adults and children.16

Dr. Spencer: Of importance is the fact that these disorders are not benign. In some samples,17–19 comorbid disorders, particularly anxiety disorders, were shown to be predictors of worse functioning.

Dr. Newcorn: Distress within the family also increases when ADHD is compounded by comorbid anxiety.

ADHD Comorbidity: Age and Differentiation

Dr. Adler: Are disorders comorbid with ADHD more clearly differentiated in adulthood than in childhood and adolescence?

Dr. Spencer: Dr. Barkley noted that the traditional childhood disorders can transition into adult disorders. If a patient has a particular disorder, he or she is likely to have certain other comorbid disorders as well. Familial genetic specificity is unusual in that the disorders are not all the same within the family.11

Dr. Newcorn: Certain disorders seem to cluster together. For example, children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety disorders often have disruptive disorders.

Dr. Barkley: Such groupings are certainly evident in adults. In a recent study,20 nearly 100 adults with ADHD were compared with a clinical control group without ADHD and with a community control group. The group that was diagnosed with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) carried an increased risk for major depression, dysthymia, and oppositional defiant disorder. This clustering of comorbidity, as Drs. Spencer and Newcorn mentioned, should be appreciated. When anxiety disorders are comorbid with ADHD, clinicians typically see anxiety disorders presenting with other disorders.

Dr. Newcorn: There has been considerable interest3 in whether the high rate of comorbidity of ADHD with anxiety disorders, mood disorders, disruptive behavior disorders—such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder—as well as a variety of other disorders offers a way to define homogeneous subgroups within the larger ADHD category, with the different comorbid subgroups having similarities in clinical presentation, longitudinal course, risk factors, and treatment response.

Dr. Weiss: Discussion thus far has been based on patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM–IV)21 criteria. In our study22 of 98 adults with ADHD, we found, using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM–IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I), that 33% had current comorbid anxiety or mood disorders and 53% of the patients met SCID-I criteria for a lifetime mood or anxiety disorder. However, many other patients had a fairly distinct syndrome that did not meet full diagnostic criteria but was associated with subjective impairment. These people were aware that owing to their ADHD, they were in danger of not being punctual, procrastinating, not meeting expectations, and of being demoralized through stigmatization. As a result, they would become anxious, and once they were anxious, their ADHD symptoms worsened. The effects of this syndrome can become a lifelong vicious circle. The intertwining of problems with anxiety, executive function, and attention over the course of a lifetime can make deciphering whether one deficit is primary a difficult task for the clinician.

Therefore, even beyond the counting of those patients who meet full diagnostic criteria, assessment of the types of associated symptoms that often present with the core symptoms of ADHD, such as anxiety and depression, may reveal a significant level of impairment, which should be considered in developing a treatment plan.

Dr. Adler: When looking at treatment data, clinicians should differentiate between patients who meet formal diagnostic criteria for an anxiety disorder with ADHD and patients affected by anxiety feeling states. Scales that are specifically designed to measure anxiety disorders may not register these feeling states.

Dr. Weiss: We specifically found that the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) and the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HAM-D) did not measure feeling states.22 We looked at response to paroxetine, dextroamphetamine, or psychotherapy and saw robust improvements on the Clinical Global Impressions for Improvement scale (CGI-I), but the HAM-D scores did not change. We need to better define what some of these anxiety symptoms are and how these symptoms impair function. Using the SCID-I diagnosis of a lifetime internalizing disorder as a moderator of treatment outcome, we found that patients with lifetime internalizing disorders had attenuated responses to stimulants. This suggests that the feeling states represented by subthreshold internalizing symptoms are not captured by the HAM-A scale nor the HAM-D scale, but are nonetheless functionally important predictors of treatment outcome.

Selection bias must be considered when discussing outcome of treatment. For example, data from the MTA23 look promising in that stimulant treatment worked well in the population, and one third of the sample was diagnosed with anxiety disorders. But, in order to participate in the MTA, a researcher had to identify the patient's primary impairment as ADHD and the secondary impairment as anxiety.2 Patients identified as having ADHD with secondary anxiety are much more likely to be stimulant responders than patients who visit an anxiety clinic and whose primary impairment is severe anxiety coupled with a secondary attention problem. Selection bias impacts not just prevalence but treatment outcome as well.

Dr. Adler: What symptoms bring these patients to a clinic for treatment?

Dr. Barkley: Presentation and history may differ between children and adults, if only because adults and children respond to stress differently.24 Children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety have a great deal of personal and family distress and have often experienced emotionally traumatic events.25 These children also have a high risk of being bullied or abused. Research on bullying among children with ADHD has shown that those most likely to experience bullying are the smallest and most anxious children.26 As part of the evaluation, the clinician would want to search for these social factors. Such social difficulties may even be the reason that the child is referred for treatment, rather than more ADHD-specific symptoms.

Pharmacotherapy for ADHD

Dr. Adler: What is our current understanding of the treatment paradigm for ADHD with comorbid anxiety? Beginning with children and adolescents: do extant data show which disorder should be treated first? What agents do clinicians tend to use for treating each disorder? In terms of stimulants or nonstimulants, which treatment tends to improve which disorder?

Dr. Newcorn: Studies27–29 in the early 1990s suggested that children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety disorders were less responsive to stimulant treatment than children with ADHD alone. These children also had higher rates of side effects from stimulants, including tics.

Dr. Barkley: Several studies27–34 found a link between internalizing symptoms and a reduced response to methylphenidate. Two large recent studies are the exceptions: the MTA study35 and the study by Abikoff et al.36 Neither of these new studies found a connection between anxiety and stimulant response.

Dr. Newcorn: Also, a study from the Toronto group (Tannock et al).37 reported lower stimulant response rates in the presence of comorbid anxiety. But a larger, more recent study32 from the same group has now found that response to methylphenidate was not significantly reduced in the presence of comorbid anxiety disorders. This more recent finding is consistent with the finding of the MTA study.35

Dr. Barkley: No clear trend has emerged from these studies. Perhaps response rates to stimulant therapies in ADHD patients with comorbid anxiety have to do with the type of anxiety disorder the patient has, or, as Dr. Weiss pointed out, which disorder is the more impairing disorder at clinical presentation. Researchers and clinicians have yet to find a definitive answer to this issue. Therefore, I teach residents to proceed with caution when using stimulants with patients who have comorbid anxiety.

Dr. Newcorn: Stimulants can be used in this population as long as the treatment is changed if the response to the stimulant is not adequate or other problems arise.38

Dr. Weiss: Have any researchers dissected the methodological differences between the 8 negative studies27–34 and the 3 positive studies35–37 of pharmacotherapy use in children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety? If the methodological differences were closely examined, that examination could lay the foundation for an accurate interpretation of why the findings are different.

Dr. Barkley: The earlier studies27–34 used dimensional ratings of anxiety, like the Child Behavioral Checklist, whereas the MTA2 and the Abikoff et al.36 studies used diagnoses more closely aligned with the DSM. The obvious methodological problem in the use of different scales is simply that anxiety disorders were measured differently in the 2 studies, which can alter diagnosis. Perhaps there are other methodological inconsistencies between the positive studies and the negative studies.

Dr. Weiss: In order to develop a research methodology that can provide meaningful evidence on management of ADHD and anxiety, several innovations are required. First, symptoms common to both disorders must be distinguished from symptoms unique to only one disorder. For example, improvement in restlessness and tension in the management of ADHD may represent a secondary gain of improvement in ADHD itself, rather than improvement in a specific anxiety disorder. Second, determining the extent to which remission of one disorder will drive improvement in the other is necessary. For example, a patient with severe GAD who is constantly worried and responds fully to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) may no longer experience problems with forgetfulness or attention. Third, rating scales for anxiety that emphasize cognitions that form the hallmark of the disorder, are not present in ADHD, and are not common side effects of treatment are needed. The essence of GAD is worry, phobia is fear, PTSD is terror, and OCD is intolerance of uncertainty. With scales that emphasize sleep, headache, gastrointestinal complaints, and other generic problems, distinguishing whether the improvement brought about by our treatments is pathognomonic is difficult. Anxiety scales that do not include associated symptoms of ADHD and generic physical problems are essential to determining whether treatments are affecting one disorder or both. Finally, research in comorbid ADHD and anxiety requires a broader view of outcome than looking at treatment response in symptoms for each disorder alone. Discrepancies in previous research are often the result of looking at very different outcomes. Studies that evaluate whether treatment is easily tolerated, whether it is possible to treat ADHD in patients with anxiety, or whether neuropsychological testing outcomes are comparable in ADHD versus ADHD with anxiety all focus on very different issues.

Dr. Newcorn: Data on comorbidity with multiple disorders would also help clinicians. Research has mainly examined ADHD in combination with 1 class of disorders at a time, such as ADHD and anxiety disorders, ADHD and mood disorders, or ADHD and oppositional defiant and conduct disorders. However, patients can certainly have more than 2 disorders at a time, and often do.4 As Dr. Barkley noted, the confluence of, for example, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and disruptive disorders has a very different clinical presentation from ADHD and anxiety disorder when there is not also disruptive behavior or if ADHD and anxiety disorders co-occur with a different comorbid disorder, such as tic disorder. Perhaps there is an opportunity, by examining comorbidity of multiple disorders, to begin to understand the differences in patient outcomes.

Dr. Weiss: Both ADHD and anxiety tend to be long-standing developmental disorders, and variance in response to treatment may depend on the patient's difficulties at the time he or she presents for help.

Dr. Adler: What about the use of nonstimulant medication in children and adolescents?

Dr. Barkley: Kratochvil et al.39 compared the efficacy and safety of atomoxetine plus placebo (N = 46) versus atomoxetine plus fluoxetine (N = 127) in children with ADHD and concurrent symptoms of depression or anxiety. The groups were randomly assigned to either fluoxetine or placebo for 8 weeks and atomoxetine for the last 5 weeks. Each treatment group experienced a reduction in ADHD symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and depressive symptoms. The completion rates and the discontinuation rates for adverse events were both similar between the 2 groups. The authors noted that the lack of a placebo-only arm was a limiting factor.

Dr. Weiss: Many symptoms overlap in anxiety and ADHD. I would like to see analyses in which researchers examine symptoms that are specific to anxiety and do not occur in ADHD. For example, researchers could look for worrying about possibilities that are unreasonable and are unlikely to occur, OCD symptoms, and specific phobias that do not occur in ADHD and do not overlap with ADHD. Symptoms of social phobia, GAD, and separation anxiety disorder also occur in individuals with ADHD. People with ADHD often experience somatic symptoms of anxiety, irritability, and restlessness.21 Separation anxiety disorder presents as an unusually heavy dependence upon another individual to be present and to accomplish tasks for the anxious patient.10 Children and adults with ADHD often rely on a parent, spouse, or other close relation to provide stability and accomplish certain necessary tasks that the patient with ADHD may be incapable of accomplishing. In social anxiety disorder, if a patient fears making inappropriate statements in public, then that patient will tend to avoid social situations. Therefore, it is of paramount importance to determine if a patient is truly in need of treatment for a specific anxiety disorder or if the anxiety symptoms are secondary to the patient's ADHD. Some patients with ADHD find that their anxiety symptoms improve when their clinician treats only their ADHD symptoms. When differentiating social anxiety disorder from consequences of ADHD, clinicians can ask their patients whether they avoid social situations because of a long history of inappropriate social behaviors or because they are overwhelmed by being with people irrespective of concerns about their behavior.

Dr. Adler: If a patient has a robust anxiety disorder and ADHD, what combination pharmacotherapy should be used? Should combinations include SSRIs or buspirone, with stimulants or nonstimulants, for children and adolescents?

Dr. Spencer: Those types of combinations are often used. Fortunately, there is no pharmacokinetic interaction between the typical agents used for anxiety, like SSRIs and buspirone, and stimulants, although there is an interaction between atomoxetine and certain SSRIs such as fluoxetine secondary to P450 2D6 interactions.39 The main issue is which combination is best for which patient and how does each drug work in that context.

Abikoff and colleagues36 enrolled only subjects who met DSM-IV criteria for both ADHD and anxiety disorders. Researchers tend to exclude patients with comorbidities from ADHD studies. First, children were treated with methylphenidate or another stimulant, children whose ADHD improved but anxiety persisted had fluvoxamine or placebo added to their treatment. The sample size was small, with 10 boys and girls aged 6 to 17 years who had been taking stimulant regimens other than methylphenidate and 32 boys and girls aged 6 to 17 years treated with methylphenidate alone. Twenty-five of these boys and girls taking stimulant pharmacotherapy alone had decreased ADHD symptoms but remained anxious. These boys and girls were randomly assigned to 8 weeks of methylphenidate plus fluvoxamine or methylphenidate plus placebo. No differences in response rates were found between the fluvoxamine and placebo groups on the Pediatric Anxiety Rating Scale or on the CGI-I. The drugs were well tolerated. This study suggests that treatment for comorbid anxiety in children should be attempted because anxiety symptoms may persist despite successful treatment of ADHD, although the benefit of fluvoxamine augmentation was not apparent in the study.

Dr. Newcorn: In the study by Abikoff et al.36 the benefit of adding fluvoxamine for anxiety was uncertain; the number of subjects studied was insufficient to make that determination. While combined treatment may indeed be helpful, it would be easier to make that recommendation if there was a more robust indication of benefit, particularly as additional treatments add risk of additional adverse effects.

The finding that successful stimulant treatment did appear to reduce anxiety in a subgroup of subjects treated in the study by Abikoff et al.36 is difficult to interpret, since stimulant treatment of ADHD is likely to result in children feeling more confident in performance situations, whether social or academic.32 Therefore, it is difficult to distinguish whether apparent improvement in anxiety symptoms following ADHD treatment is due to a direct effect of the treatment on the anxiety disorder itself or to secondary reduction in anxiety from treatment of ADHD symptoms that results in improved self-confidence in performance situations.

Dr. Weiss: The use of SSRIs in children and adolescents is an area in which variances in research methods have led to clinical confusion. When evidence-based strategies are unavailable, physicians must act in clinically reasonable ways. A child with a severe anxiety disorder is substantially impaired. The risk-benefit ratio for the pediatric use of SSRIs in depression is relatively high, in that response versus placebo is poor. However, the evidence for the efficacy of SSRIs for the treatment of anxiety in children is robust, and the risk-benefit ratio is lower.40 In locations where psychological treatments are not available as alternatives to medication, it is especially important to assure that we do not make a mistake and fail to treat serious and debilitating anxiety disorders in children.

Dr. Adler: There are even fewer data on treatment with stimulants and nonstimulant medications concerning the treatment of adults with ADHD and comorbid anxiety.

Dr. Spencer: To my knowledge, the data concerning comorbid anxiety treatment in adults with ADHD who take stimulants are mostly anecdotal. To some degree, when researchers have studied stimulant treatment in adults with ADHD, acknowledgment of anxiety has been focused on whether a history of an anxiety disorder will be associated with a poor response to treatment. To my knowledge, there is no systematic study currently looking at anxiety comorbidity and stimulant treatment in adults.

Dr. Adler: Researchers have not found a high rate of efficacy for stimulant and nonstimulant treatment of comorbid anxiety symptoms, even when using scales designed for anxiety disorders like the HAM-A. The next generation of studies will move on to more feeling-state questionnaires with which investigators can try to peel anxiety feelings apart.

Dr. Spencer: In our studies,30,31,41–43 my colleagues and I used the HAM-A and HAM-D scales for orientation. We were concerned that higher doses of stimulants in adults could be anxiogenic. The answer was no. For the majority of patients, the scales were completely flat across the studies and, despite robust treatment with stimulants and nonstimulants, HAM-A and HAM-D scores remained even. The medications were well tolerated and did not make anxiety disorders worse, according to the HAM-A. However, the Hamilton scales have a blind spot because they are mostly focused on somatic symptoms of anxiety and are less sensitive to other features of anxiety such as cognitive impairments like worry and fear.

Nonpharmacologic Treatments for ADHD

Dr. Adler: What should the role of nonpharmacologic treatments be when combating ADHD and comorbid anxiety disorders in children, adolescents, and adults?

Dr. Barkley: The MTA study35 found that children with ADHD and anxiety had among the best responses to the psychosocial treatment package—better than community care and approaching medication-based treatment results.

One study44 using social skills training suggests a similar finding: the anxious children responded better to social skills training than the nonanxious children. Children and teenagers with ADHD and comorbid anxiety disorders may be the subset of patients with ADHD in which behavioral interventions or psychological interventions can prove the most effective.

Dr. Newcorn: In the MTA study,19 two thirds of the children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety disorder also had a comorbid behavioral disorder; the robust improvement with behavioral therapy alone was most evident in the group without conduct disorder. Other analyses23 from the MTA suggest that the group with ADHD and both anxiety and conduct disorder did best with combined medication and behavioral therapy. However, children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety but without conduct disorder had similar response rates to the medication alone and to the behavioral treatments alone. One interesting aspect of the MTA results is that although psychosocial treatment alleviated both ADHD symptoms and internalizing symptoms, the treatment was directed only at symptoms of ADHD and not anxiety or other internalizing symptoms.

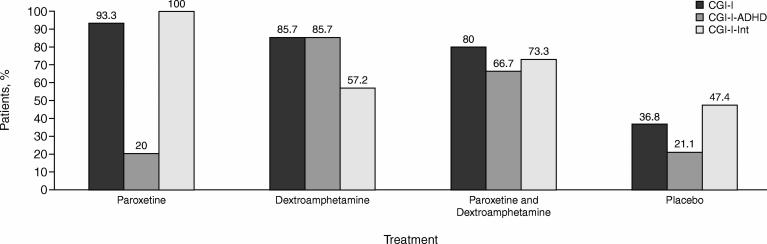

Dr. Weiss: My colleagues and I22 recently published a study of 98 adults selected for ADHD only in a 5-site study. Patients were excluded from the study if they had a current anxiety or mood disorder that required treatment. Levels of internalizing symptoms varied and most of the patients did not meet diagnostic criteria for anxiety, although half of the patients were found to have at least 1 lifetime anxiety or mood disorder. At the start of the study, patients were randomly assigned to receive 20 weeks of problem-focused therapy and one of the following: paroxetine, dextroamphetamine, paroxetine plus dextroamphetamine, or placebo.

Findings from our study may lay the foundations for replication in other research. At the onset of the study, HAM-A scores were above normal but below clinical range. Conversely, the CGI-I scale scores specific to anxiety and depression showed that 100% of the patients taking paroxetine alone described their moods and anxiety as very much improved (Figure 2), even though the Hamilton scores were low. The patients also described improvement in areas the Hamilton scales do not measure: dysphoria, explosive reactions, irritability reactivity, and other symptoms that are not included in the DSM-IV criteria, but were nonetheless of concern to patients and so rated improved on the CGI-I scale.

Figure 2.

Treatment Response of Adult ADHD Patients to the Stimulant Dextroamphetamine or the SSRI Paroxetine Alone and in Combinationa

Another finding of that study was that although mood improved with paroxetine alone and ADHD improved with dextroamphetamine alone, combination pharmacotherapy was not found to lead to greater overall improvement than monotherapy. Combination treatment was associated with more adverse events and more psychiatric adverse events than either form of monotherapy. Also, psychological therapy plus medication was more effective than psychological therapy plus placebo.

The study results show a need for more information on the nature of the internalizing symptoms of adults with ADHD. The symptoms do not fit perfectly with DSM-IV criteria or measures on rating scales, yet these symptoms cause difficulties that are a source of distress to the patient and responsive to treatment.

Dr. Adler: There are no real guidelines for using medications together in an adult population and no guarantee that improved effectiveness across both disorders will be achieved with drug combinations. Results may vary as a function of dose and other considerations. Cognitive-behavioral therapy is another treatment that is effective, but it is important to differentiate CBT for anxiety from CBT for ADHD.

Dr. Spencer: Safren et al.45 examined the addition of CBT in adults (N = 31) with ADHD who were not fully responding to traditional pharma-cotherapy. The type of CBT used was for organization rather than for anxiety, but anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed in addition to ADHD severity. At endpoint, those who received CBT had significantly lower ratings of ADHD symptoms than those who continued taking pharmaco-therapy alone (independent evaluatorrated symptoms, p < .01; CGI score, p < .002; self-reported symptoms, p < .0001). Treatment response was 13% in the pharmacotherapy-alone group and 56% in the CBT plus medication group.

Simple human contact may lessen anxiety symptoms, or perhaps some anxiety is based on organizational issues in patients with ADHD. It would be illuminating to have a study of anxiety-targeted therapy that used the best measures and methodology possible to study the anxiety itself.

Dr. Newcorn: Psychosocial treatment is useful in targeting very specific types of behaviors, focusing on one or another setting, or even a specific time of the day. It is therefore possible to use psychosocial interventions for different conditions together and also to use psychosocial treatment in combination with medication.

Dr. Adler: How do psychosocial treatments differ in children versus adults? Experts in the field differ on whether psychosocial treatments should be used as primary therapies or as augmentation strategies.

Dr. Newcorn: It varies more by the individual than the age group. For some children we might be able to use psychosocial treatment as the primary modality, without medication. But for many other children, combining medication and psychosocial treatment provides a much more robust effect. The same is probably true in adults, although there has been less systematic study in adults. Also, the nature of the psychosocial treatment will differ according to age. In children, behavioral treatment is most often directed at improving self-regulatory capacities through parent behavior-management approaches. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, although less well established for ADHD, would presumably be better suited to adolescents and adults and would generally target different domains of function: task persistence and completion rather than behavioral regulation.

Dr. Adler: If CBT is being considered in the treatment decision pathway, the availability and quality of the CBT therapist should be considered.

Dr. Weiss: In the real world, a problem with CBT is that some therapists are well qualified and effective while others are not. Success may be dependent on access to a skilled therapist. Cognitive-behavioral therapy may present a cost problem for patients, as well. Patient acceptance of the treatment modality is critical to its success. Psychological treatments for anxiety disorders may be very effective in those interested and able to use them and less effective for the population as a whole.

A major difference between children with ADHD and adults with ADHD is that children have less insight. Children do not always see the need for psychological treatment, and young boys with ADHD and comorbid anxiety may be particularly avoidant of talking therapy, especially in groups. We know very little about how improvement in ADHD symptoms may improve access and response to psychological treatment, but disruptive children may have more difficulty complying with and using psychotherapy. We have found that our CBT group for anxiety (“Taming the Worry Dragons”) is most effective for children with comorbid anxiety and ADHD if the ADHD is adequately controlled.

When the symptoms of ADHD in adults are addressed for the first time, these adults must still catch up on a lifetime of skill development, and psychosocial therapy offers that opportunity.4 When adults are in remission from ADHD, they still need to learn organizational and executive functioning skills. The experience in our clinic is much like that described in Safren's study: the majority of our adult patients are interested in further improvement when treated with CBT as well as medication. This is in contrast to the children who have neither the motivation for psychological treatment nor the need. Children who are symptom free are provided with ongoing instruction in executive function skills at school. Adults could not use this instruction when they were symptomatic as children, and now that they are symptom free still need to learn how to organize, strategize, prioritize, and plan.

Dr. Adler: The kind of psychosocial intervention used for patients with ADHD and comorbid anxiety disorders may be somewhat different than the type of intervention for patients with ADHD alone. The different types of therapies need to be better established.

Dr. Barkley: Anxiety disorders in children are often missed by parents. If a child is clinically evaluated for ADHD through parental interviews alone, anxiety disorders may go undetected and untreated. Clinicians should personally interview juvenile patients.

Dr. Spencer: Simply being aware of the possibility of comorbid anxiety disorders occurring with ADHD is beneficial for detection and diagnosis. Past prevailing wisdom taught that ADHD was an externalizing disorder and anxiety was an internalizing disorder; therefore, having one protected against developing the other. The discovery4 that these disorders more commonly occur together rather than alone went against clinical lore. Also, many people are not anxious in the presence of physicians; patients seeking help are calmed by a reassuring clinical setting. Therefore, questions about possible anxiety symptoms should be part of the general review and not asked just when reviewing patients who initially complain of anxiety.

Dr. Weiss: This subject area needs more exploration in research.

Dr. Adler: I want to thank the faculty. This wide-ranging discussion has covered a broad topic and highlighted the importance of understanding anxiety disorders that are comorbid with ADHD, how commonly they occur, their influence on pharmacotherapy, how pharmacotherapies affect these symptoms and disorders, and the role of nonpharmacologic therapies in these disorders.

Drug names: atomoxetine (Strattera), buspirone (BuSpar and others), dextroamphetamine (Dexedrine, Dextrostat, and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), methylphenidate (Ritalin, Metadate, and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others).

Disclosure of off-label usage: The chair has determined that, to the best of his knowledge, atomoxetine is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and depression or anxiety; buspirone is not approved for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents; fluoxetine is not approved for the treatment of ADHD and depression or anxiety in children; fluvoxamine and methylphenidate are not approved for the treatment of ADHD and anxiety in children; and paroxetine is not approved for the treatment of ADHD.

Faculty disclosure: In the spirit of full disclosure and in compliance with all ACCME Essential Areas and Policies, the faculty for this CME article were asked to complete a statement regarding all relevant financial relationships between themselves or their spouse/partner and any commercial interest (i.e., a proprietary entity producing health care goods or services) occurring within the 12 months prior to joining this activity. The CME Institute has resolved any conflicts of interest that were identified. The disclosures are as follows: Dr. Adler is a consultant for Abbott, Cephalon, Cortex, Eli Lilly, McNeil, Neurosearch, Novartis, Pfizer, and Shire; has received grant/research support from Abbott, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Cortex, Eli Lilly, McNeil, Merck, National Institute on Drug Abuse, Neurosearch, Novartis, Pfizer, and Shire; and is a member of the speakers/advisory boards for Cortex, Eli Lilly, McNeil, Neurosearch, Novartis, Pfizer, and Shire. Dr. Barkley is a consultant for Eli Lilly, Shire, McNeil, and Janssen-Ortho; has received grant/ research support from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and Eli Lilly; has received honoraria from Houston School District IV, National Institute for Learning Disabilities, Berkshire Farms, Oakland School District–Michigan, Spain Child Neurology Society, New England Educational Institutes, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Russian Foundation for ADHD Children, Medical University of South Carolina, Norwegian DAMP Association, Royal College of Medicine–London, Denmark DAMP Association, Suffolk ADHD Parents Association–England, Oregon Health Sciences University, National Association for School Psychology, Aspen Educational Centers, Maryland School Psychology Association, Quebec City Hospital, Manitoba School Psychology Association, South Carolina Council for Emotional and Behavioral Disorders, Temple University Medical School, ALENHI Parents Association–Spain, Fundacion Activa–Spain; and is a member of the speakers/ advisory board for Eli Lilly. Dr. Newcorn is a consultant for, a member of the speakers/ advisory boards for, and has received honoraria from Eli Lilly, McNeil, Novartis, Shire, Cephalon, Cortex, and Pfizer, and has received grant/research support from Eli Lilly, McNeil, Shire, and Novartis. Dr. Spencer receives research support from Shire, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, McNeil, Novartis and NIMH; is a member of the speaker's bureaus for GlaxoSmithKline, Eli Lilly, Novartis, Wyeth, Shire, and McNeil; and is on the advisory board for Shire, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, McNeil, and Novartis. Dr. Weiss is a consultant for Novartis, Eli Lilly, Shire, and Janssen; and has received grant/ research support from Purdue, Circa Dia, Eli Lilly, Shire, and Janssen; and has received honoraria from and is a member of the speakers/ advisory boards for Purdue, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Shire, and Janssen.

Pretest and Objectives

Posttest

Registration Form

Footnotes

This Academic Highlights section of The Primary Care Companion to The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry presents the highlights of the teleconference roundtable “Managing ADHD in Children, Adolescents, and Adults With Comorbid Anxiety,” which was held September 15, 2006. This report was prepared by the CME Institute of Physicians Postgraduate Press, Inc., and was supported by an educational grant from Eli Lilly and Company.

The teleconference roundtable was chaired by Lenard A. Adler, M.D., Departments of Psychiatry and Neurology, New York University School of Medicine, New York. The faculty were Russell A. Barkley, Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, State University of New York Upstate Medical University, Syracuse; Jeffrey H. Newcorn, M.D., Department of Psychiatry and the Division of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Mt. Sinai School of Medicine, New York, N.Y.; Thomas J. Spencer, M.D., Department of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School and Department of Pediatric Psychopharmacology, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; and Margaret D. Weiss, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Psychiatry, University of British Columbia and the Provincial ADHD Program, Children's and Women's Health Centre of British Columbia, Vancouver, Canada.

Faculty disclosure appears at the end of this article.

The opinions expressed herein are those of the faculty and do not necessarily reflect the views of the CME provider and publisher or the commercial supporter.

REFERENCES CITED

- Culpepper L.. Primary care treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:51–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073–1086. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S.. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:564–577. doi: 10.1176/ajp.148.5.564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A.. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T.. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and comorbidity. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:915–927. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(05)70163-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Mick E, and Faraone SV. et al. Influence of gender on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children referred to a psychiatric clinic. Am J Psychiatry. 2002 159:36–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, and Spencer T. et al. Gender differences in a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Res. 1994 53:13–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, and Milberger S. et al. A prospective 4-year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1996 53:437–446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterson BS, Pine DS, and Cohen P. et al. Prospective, longitudinal study of tic, obsessive-compulsive, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorders in an epidemiological sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001 40:685–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Leckman JF, and Merikangas KR. et al. Depression and anxiety disorders in parents and children. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1984 41:845–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, and Keenan K. et al. Further evidence for family-genetic risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: patterns of comorbidity in probands and relatives psychiatrically and pediatrically referred samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992 49:728–738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hettema JM, Neale MC, Kendler KS.. A review and meta-analysis of the genetic epidemiology of anxiety disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:1568–1578. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.10.1568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGough JJ, Smalley SL, and McCracken JT. et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 162:1621–1627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone SV, and Spencer T. et al. Patterns of psychiatric comorbidity, cognition, and psychosocial functioning in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993 150:1792–1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler L, and Barkley R. et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006 163:716–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucklidge JJ, Brown DL, and Crawford S. et al. Retrospective reports of childhood trauma in adults with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2006 6:631–641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Adler LA, and Barkley R. et al. Patterns and predictors of attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder persistence into adulthood: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2005 57:1442–1451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biederman J, Faraone S, and Milberger S. et al. Predictors of persistence and remission of ADHD in adolescence: results from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996 35:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Swanson JM, and Arnold LE. et al. Anxiety as a predictor and outcome variable in the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2000 28:527–541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkley RA, Murphy KR, and Fischer M. The Science of ADHD in Adults: Clinic-Referred Adults and Children Grown Up. New York: Guilford. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association. 2000 [Google Scholar]

- Weiss M, Hechtman L. for the Adult ADHD Research Group. A randomized double-blind trial of paroxetine and/or dextroamphetamine and problem-focused therapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006 67:611–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Hinshaw SP, and Kraemer HC. et al. ADHD comorbidity findings from the MTA study: comparing comorbid subgroups. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001 40:147–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR.. Psychiatric comorbidities in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: implications for management. Pediatr Drugs. 2003;5:741–750. doi: 10.2165/00148581-200305110-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen PS, Shervette RE, and Xenakis SN. et al. Anxiety and depressive disorders in attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity: new findings. Am J Psychiatry. 1993 150:1203–1209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumpulainen K, Rasanen E, and Henttonen I. et al. Bullying and psychiatric symptoms among elementary school-age children. Child Abuse Negl. 1998 22:705–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolraich ML, Lindgren S, and Stromquist A. et al. Stimulant medication use by primary care physicians in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 1990 86:95–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Barkley RA, McMurray MB.. Response of children with ADHD to methylphenidate: interaction with internalizing symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1994;33:894–903. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199407000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR.. Effect of anxiety on cognition, behavior, and stimulant response in ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:882–887. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198911000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Wilens T, and Biederman J. et al. A double-blind, crossover comparison of methylphenidate and placebo in adults with childhood-onset attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995 52:434–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Wilens T.. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:456–463. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond IR, Tannock R, Schachar RJ.. Response to methylphenidate in children with ADHD and comorbid anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1999;38:402–409. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199904000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pliszka SR, Greenhill LL, and Crismon ML. et al. The Texas Children's Medication Algorithm Project: report of the Texas Consensus Conference Panel on medication treatment of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, pt 2: tactics. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000 39:920–927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rappley MD, Gardiner JC, and Jetton JR. et al. The use of methylphenidate in Michigan. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995 149:675–679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MTA Cooperative Group. Moderators and mediators of treatment response for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the multimodal treatment study of children with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1088–1096. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.12.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abikoff H, McGough J, and Vitiello B. et al. Sequential pharmacotherapy for children with comorbid attention-deficit/hyperactivity and anxiety disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 44:418–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannock R, Ickowicz A, Schachar R.. Differential effects of methylphenidate on working memory in ADHD children with and without comorbid anxiety. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:886–896. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199507000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;113:428–429. [Google Scholar]

- Kratochvil CJ, Newcorn JH, and Arnold LE. et al. Atomoxetine alone or in combination with fluoxetine for treating ADHD with comorbid depressive or anxiety symptoms. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2005 44:915–924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel L, Walkup JT.. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor use in the treatment of the pediatric non-obsessive-compulsive disorder anxiety disorders. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16:171–179. doi: 10.1089/cap.2006.16.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Biederman J, and Wilens T. et al. Efficacy of a mixed amphetamine salts compound in adults with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001 58:775–782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Biederman J, and Wilens T. et al. Effectiveness and tolerability of tomoxetine in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1998 155:693–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T.. Stimulant treatment of adult attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antshel KM, Remer R.. Social skills training in children with attention deficit hyper-activity disorder: a randomized-controlled clinical trial. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32:153–165. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3201_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safren SA, Otto MW, and Sprich S. et al. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated adults with continued symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2005 43:831–842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]