Abstract

Objective: This study examined the efficacy and tolerability of duloxetine, a dual reuptake inhibitor of serotonin and norepinephrine, for the treatment of patients with generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).

Method: Patients were ≥ 18 years old and recruited from 5 European countries, the United States, and South Africa. The study had a 9-week, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled, parallel-group design. A total of 513 patients (mean age = 43.8 years; 67.8% female) with a DSM-IV–defined GAD diagnosis received treatment with duloxetine 60 mg/day (N = 168), duloxetine 120 mg/day (N = 170), or placebo (N = 175). The primary efficacy measure was the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) total score. Secondary measures included the Sheehan Disability Scale, HAM-A psychic and somatic anxiety factor scores, and HAM-A response, remission, and sustained improvement rates. The study was conducted from July 2004 to September 2005.

Results: Both groups of duloxetine-treated patients demonstrated significantly greater improvements in anxiety symptom severity compared with placebo-treated patients as measured by HAM-A total score and HAM-A psychic and somatic anxiety factor scores (p values ranged from ≤ .01 to ≤ .001). Duloxetine-treated patients had greater functional improvements in Sheehan Disability Scale global and specific domain scores (p ≤ .001) than placebo-treated patients. Both duloxetine doses also resulted in significantly greater HAM-A response, remission, and sustained improvement rates compared with placebo (p values ranged from ≤ .01 to ≤ .001). The rate of study discontinuation due to adverse events was 11.3% for duloxetine 60 mg and 15.3% for duloxetine 120 mg versus 2.3% for placebo (p ≤ .001).

Conclusion: The results of this study demonstrate that duloxetine 60 mg/day and 120 mg/day were efficacious and well tolerated and thus may provide primary care physicians with a useful pharmacologic intervention for GAD.

Clinical Trials Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov identifier NCT00122824.

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is an illness characterized by excessive and difficult-to-control worry that is pervasive for at least 6 months (criteria A and B of DSM-IV).1 The patient's continual focus on potential danger leads not only to subjective tension and hypervigilance, but also to numerous somatic symptoms.2 As part of the DSM-IV criteria, patients with GAD must experience at least 3 of the following symptoms for more days than not: muscle tension, irritability, feelings of being keyed up, fatigue, difficulty concentrating, and sleep disturbance. In addition to these diagnostic symptoms, patients with GAD also report a greater number of somatic symptoms compared with normal controls, particularly for skeletomuscular pain, headache, gastrointestinal distress, and cardiovascular symptoms.3

Although patients with GAD often express that they worry about “everything,” their most predominant concerns are about family, personal health, and the health of others.4 Thus, the mutual reinforcements among the process of worry, focus on health, and the experience of multiple somatic symptoms result in patients with GAD being high utilizers of medical services. In a survey of over 20,000 primary care patients, patients with GAD without comorbid depression were 1.6 times more likely to have seen their primary care physician at least 4 times during the past year compared with other primary care patients.5 Within these large-scale studies, GAD has also been shown to be the most prevalent anxiety disorder among primary care patients, with estimates ranging from 5% to 10% and occurring twice as frequently in women as in men.5,6

The majority of patients with GAD receive treatment for their anxiety from their primary care physicians or medical specialists (e.g., gastroenterologists) rather than psychiatrists or other mental health professionals.7 Within the primary care setting, GAD patients receive heterogeneous interventions that include 5 different classes of medications as well as herbal treatments.5 One reason for this treatment heterogeneity may be due to patients' greater focus on their somatic rather than psychic anxiety symptoms, which results in physicians providing symptomatic treatment—for example, hypnotics for insomnia—rather than interventions for the GAD syndrome. Another reason for the different pharmacotherapies is that GAD may involve dysregulation of several neurotransmitter systems, including norepinephrine, serotonin, and γ-aminobutyric acid.8 Different pharmacologic agents that target 1 or more of these systems often are used, with differing degrees of effectiveness, for the treatment for GAD.

Given the variety of available interventions, selecting the appropriate therapeutic medication for GAD can be challenging and requires consideration of the medication's efficacy, tolerability, and long-term management.9 Although benzodiazepines and sedatives are frequently prescribed for the treatment of GAD, they may not be an optimal choice due to tolerance, dependence, and efficacy concerns.10 Current consensus recommendations are to use selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs) as the first line of treatment for GAD, regardless of whether the GAD occurs as a primary or comorbid condition.11,12 Although SSRIs and SNRIs as a group have each demonstrated efficacy for GAD, the current outcome literature also indicates a continued need for treatment development, especially in order to obtain the goal of GAD remission as well as response.10

Duloxetine is a dual reuptake inhibitor of both serotonin and norepinephrine that has demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of major depression and diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain.13,14 Within studies of major depression, duloxetine was shown to significantly reduce anxiety symptoms as measured by the Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression15 anxiety/somatization subscale and the psychic anxiety item; these questions assess tension, worry, and associated somatic symptoms.16 Preclinical studies using animal models also support the potential of duloxetine to be anxiolytic.17 Therefore, duloxetine may be an effective intervention for patients with GAD.

The purpose of the present study was to examine the efficacy, tolerability, and safety of duloxetine 60 mg/day or duloxetine 120 mg/day for the treatment of adults with GAD.

METHOD

Study Design

This multicenter, randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study consisted of 4 phases: screening/washout phase (up to 30 days); 1-week, single-blind, placebo lead-in phase; 9-week acute therapy phase; and 2-week discontinuation phase. The study was conducted from July 2004 to September 2005. During baseline and screening phases, patients underwent diagnostic and clinical evaluations, a physical examination, laboratory chemistries, and an electrocardiogram. Diagnosis was determined by psychiatrists based on clinical interview supplemented by the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV.18 Raters from each research center underwent training in the Structured Interview Guide for the Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (SIGH-A)19 and were evaluated for their interview skills using a modified version of the Rater Applied Performance Scale.20 In mock Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety (HAM-A) interviews, raters were assessed for interview style (question clarification and follow-up, rapport), standardization (adherence, neutrality), and interrater scoring reliability. Raters had to demonstrate sufficient competence in these areas to be approved as an acceptable rater for the study.

After a single-blind placebo lead-in week, patients were randomly assigned to receive duloxetine 60 mg once daily, duloxetine 120 mg once daily, or placebo. As the HAM-A total score was not part of the study entry criteria, treatment randomization was stratified by HAM-A total score at the randomization visit in order to ensure that severity did not differ between groups. Based on prior studies of the HAM-A for patients with GAD (e.g., Shear et al.19), we selected HAM-A total scores < or ≥ 22 for the purpose of stratification. Patients in both duloxetine treatment groups were started with duloxetine 60 mg. If there were tolerability concerns, the dose could be lowered initially to 30 mg, but all patients were gradually increased to their randomly assigned dose over a 2-week period. Study visits were conducted at weeks 1, 2, 4, 6, and 9 of double-blind treatment. After the acute therapy phase, patients who were taking duloxetine were randomly assigned to either abrupt discontinuation of their medication or a gradual tapering over a 2-week period.

Patient Selection

Patients were recruited from 42 outpatient treatment centers in 7 countries (Finland, France, Germany, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, and United States). Patient-related study materials were translated into the official language for each country. Recruitment methods varied by country and included media and Internet advertisement, primary care referrals, and mental health referrals.

To be eligible for entry into the study, patients had to be at least 18 years of age and have a primary diagnosis of DSM-IV–defined generalized anxiety disorder. Each patient's GAD illness had to be at least moderate in severity as indicated by the following inclusion criteria: a rating of at least 4 (moderate) on the Clinical Global Impressions-Severity of Illness scale; a Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) anxiety subscale score ≥ 10; a Covi Anxiety Scale21 total score ≥ 9; and the Covi Anxiety Scale total score had to be greater than the Raskin Depression Scale22 total score. The Raskin Depression Scale consists of 3 items rated on a 5-point scale, and no item could be rated > 3. Patients were required to be medically healthy as determined by physical examination, electrocardiogram, and laboratory results (renal, liver, and thyroid function tests). Women of potential childbearing status were required to use adequate contraceptive precautions.

Patients were excluded if they met criteria for a recent (past 6 months) diagnosis of major depressive disorder or substance abuse/dependence; a past-year history of panic disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or eating disorder; or a lifetime history of psychotic, bipolar, or obsessive-compulsive disorder or psychosis. Patients were required to be free of psychotropic medications at least 2 weeks prior to randomization, with the exception of 4 weeks for those patients receiving fluoxetine. Additional exclusion criteria included lack of response of GAD to 2 prior adequate trials of antidepressant or benzodiazepine treatments, any medical illness that would contraindicate the use of duloxetine, psychotherapy that was initiated within 6 weeks prior to enrollment, and the use of any concomitant medications that could interfere with the assessment of efficacy and safety of the study drug. Patients also underwent urine drug screens for benzodiaze-pine or illicit drug use. Antihypertensive medication was allowed if the patient had been on a stable dose regimen for 3 months.

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki23 and country-specific ethical review guidelines. Each site's ethical review board reviewed and approved the study protocol. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Efficacy and Tolerability Assessments

The primary efficacy measure was the total score on the HAM-A,24 which was administered at each visit. The HAM-A is a 14-item clinician-rated instrument in which items are rated from 0 (not at all present) to 4 (severely disabling); higher total scores indicate greater distress and impairment. Secondary efficacy measures included the HAM-A psychic factor (sum of HAM-A items anxious mood, tension, fears, insomnia, concentration, depressed mood, and behavior at interview), HAM-A somatic factor (sum of HAM-A items somatic muscular, somatic sensory, cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, and autonomic symptoms), and the patient-reported HADS.25 The HADS consists of two 7-item sub-scales (anxiety and depression); total subscale scores range from 0 to 21, with higher scores indicating greater symptom severity.

Additional secondary outcomes focused on improvements in overall symptom severity and functioning. Patient improvement was assessed by raters using the Clinical Global Impressions-Improvement scale (CGI-I)26 and by patients using the Patient Global Impressions-Improvement scale (PGI-I).27 Both scales consist of a 7-point global rating in which 1 = very much improved, 4 = no change, and 7 = very much worse. Patients also completed the Sheehan Disability Scale,28 on which they rated their impairment in 3 life domains, work, social, and family/home management, using a 0-to-10 scale on which 0 = none and 10 = extreme. The global functional impairment score is the sum of the 3 items. Patients were also assessed for the presence and severity of painful somatic symptoms associated with GAD using Visual Analogue Scales for Pain29; however, the results from these assessments will be reported elsewhere.

At each visit throughout the study, tolerability was assessed through collection and monitoring of spontaneously reported adverse events.

Statistical Methods

All analyses were conducted on an intent-to-treat basis. All randomly assigned patients were included in the safety analyses, and all randomly assigned patients with at least 1 postbaseline measurement were included in the efficacy analyses. The study was designed to have an 80% power to detect a difference of 2.0 points in the HAM-A total score, assuming a common standard deviation of 6.0, a 2-sided significance level of .05, and that 10% of the patients would miss postbaseline HAM-A total score data. This criteria set the sample size at 160 patients per treatment group. All investigative sites with fewer than 12 randomly assigned patients were pooled together and considered as a single site.

The primary efficacy analysis was the mean change from baseline to endpoint in the HAM-A total score during the 9-week, double-blind, acute therapy phase. For continuous efficacy variables, with the exception of CGI-I and PGI-I scores, treatment group differences were examined using an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) model with treatment and investigator as main effects, and the baseline score as the covariate. The CGI-I and PGI-I endpoint scores were analyzed using an analysis of variance (ANOVA) model with treatment and investigator as fixed effects. In addition, a mixed-effects repeated-measures (MMRM) analysis was done to assess change over time.30 The MMRM model included the fixed categorical effects of treatment, investigator, visit, and treatment-by-visit interaction as well as the continuous fixed covariates of baseline and baseline-by-visit interaction.

Response was defined as a ≥ 50% reduction from baseline in HAM-A total score at endpoint; sustained improvement rates were defined as a ≥ 30% reduction from baseline in HAM-A total score at visit prior to endpoint that was sustained to last visit; and remission was defined as a HAM-A total score ≤ 7 at endpoint.31 Comparisons of the treatment groups for these categorical efficacy measures were analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test controlling for investigator. Categorical tolerability measures were analyzed using Fisher exact test.

For the above analyses, baseline was defined as the last nonmissing measurement prior to randomization (visits 1 through 3). Endpoint was defined as the last nonmissing postbaseline measurement in the acute therapy phase (last observation carried forward, visits 4 through 8). Mean refers to the least-squares mean, which is the model-adjusted mean for the respective analysis. Efficacy results presented in this article are from an ANCOVA/ANOVA model unless otherwise specified. Statistical comparisons were based on 2-sided, .05 significance levels.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

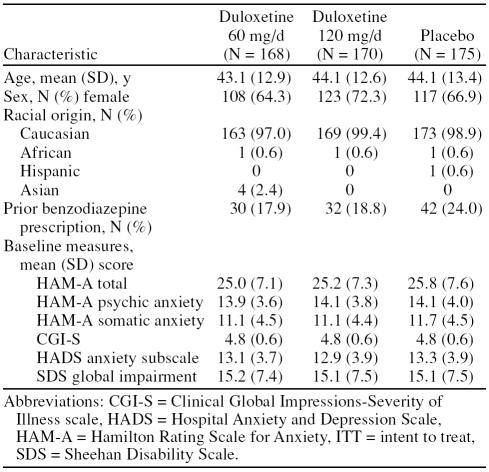

A total of 639 patients were evaluated for the study; 126 failed to meet entry criteria or declined to participate in the study. The remaining 513 patients were randomly assigned to receive duloxetine 60 mg/day (duloxetine 60, N = 168), duloxetine 120 mg/day (duloxetine 120, N = 170), or placebo (N = 175) treatment. There were no statistically significant differences between groups at baseline in demographics or illness severity measures (Table 1). The majority of the sample was female (67.8%) with a mean age of 43.8 years (SD = 13.0). The mean baseline HAM-A scores indicated moderately severe GAD.

Table 1.

Demographic and Psychiatric Characteristics of ITT Sample of Adults With Generalized Anxiety Disorder

Of the randomly assigned patients, 75.8% of the sample completed the 9-week acute therapy phase. Duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients had significantly greater rates of discontinuation due to adverse events compared with placebo-treated patients (duloxetine 60 = 11.3%, duloxetine 120 = 15.3%, vs. placebo = 2.3%, p ≤ .001), whereas placebo-treated patients were more likely to discontinue due to lack of efficacy (duloxetine 60 = 1.8%, duloxetine 120 = 3.5%, vs. placebo = 13.1%, p ≤ .001). There were no statistical differences in reasons for discontinuation between the duloxetine treatment groups.

Efficacy

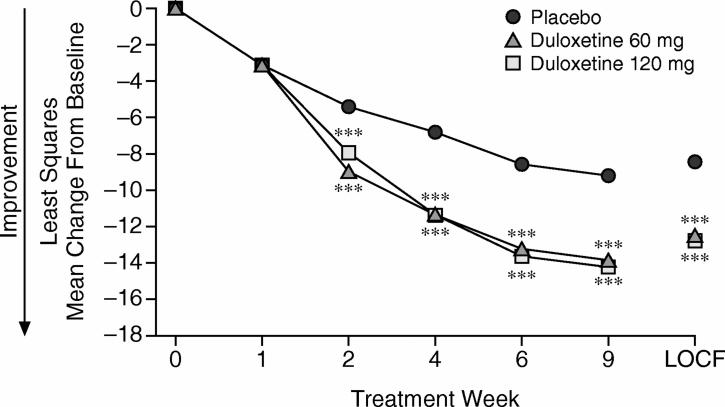

Patients who were treated with duloxetine 60 mg/day or 120 mg/day experienced significantly greater improvement in anxiety symptom severity compared with placebo-treated patients as demonstrated by the primary measure, HAM-A total score (both duloxetine groups vs. placebo, p ≤ .001). Duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients experienced mean decreases in HAM-A total score that were more than 4 points greater than the decreases shown by placebo-treated patients; the mean change represents a 49% decrease in HAM-A total score from baseline for duloxetine-treated patients. Differences between both duloxetine groups compared with the placebo group were significant as early as 2 weeks after treatment and remained significant at each subsequent visit (MMRM analysis) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Mean Change From Baseline to Endpoint in HAM-A Total Score by Treatment Week (MMRM) and at Endpoint (week 9, LOCF)

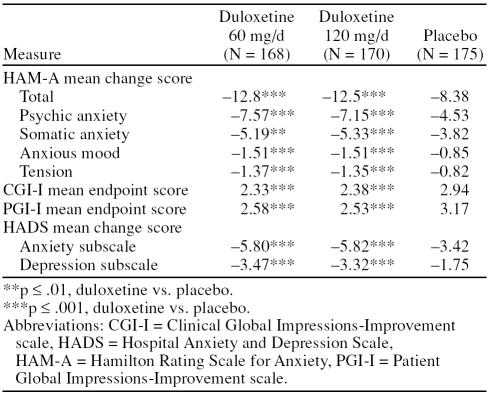

Duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients also demonstrated significantly greater improvements compared with the placebo-treated patients on each of the secondary efficacy measures: HAM-A psychic anxiety factor score, HAM-A somatic anxiety factor score, HAM-A anxious mood (item 1), HAM-A tension (item 2), and the HADS anxiety and depression subscales (both duloxetine groups vs. placebo, p values ranged from ≤ .01 to ≤ .001) (Table 2). Examination of the additional HAM-A items showed that both duloxetine groups experienced significantly greater improvement compared with the placebo group for fears (p ≤ .01), intellectual/cognitive (p ≤ .001), depression (p ≤ .001), somatic muscular (p ≤ .001 for duloxetine 60; p ≤ .01 for duloxetine 120), cardiovascular (p ≤ .01 for duloxetine 60; p ≤ .001 for duloxetine 120), respiratory symptoms (p ≤ .001), and behavior at interview (p ≤ .001). Compared with the placebo group, patients in the duloxetine 60 mg group also showed greater improvement for the insomnia item (p ≤ .001), whereas patients in the duloxetine 120 mg group were significantly more improved for somatic sensory symptom (p ≤ .01). Additionally, duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients had significantly greater improvement ratings at endpoint compared with placebo-treated patients on the CGI-I and PGI-I (both duloxetine groups vs. placebo, all comparisons, p ≤ .001).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Efficacy Results During Double-Blind Treatment

HAM-A response, sustained improvement, and remission rates were significantly higher for both duloxetine groups compared with the placebo group. Patients met criteria for treatment response at a rate of 58% for duloxetine 60 mg, 56% for duloxetine 120 mg, and 31% for placebo (both duloxetine groups vs. placebo, p ≤ .001). Similarly, duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients were significantly more likely to meet the remission criteria than placebo-treated patients (duloxetine 60 mg, 31%; duloxetine 120 mg, 38%; and placebo, 19%; duloxetine 60 vs. placebo, p ≤ .01; duloxetine 120 vs. placebo, p ≤ .001). Sustained improvement rates were also greater in duloxetine-treated patients (duloxetine 60 mg, 64%; duloxetine 120 mg, 67%) compared with placebo-treated patients (43%; both groups, p ≤ .001).

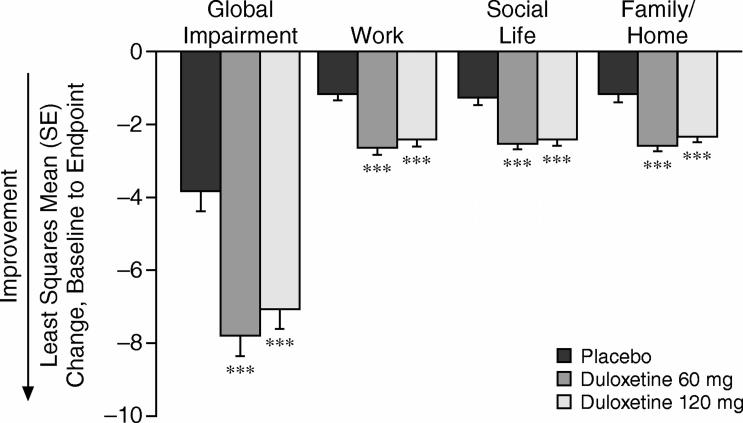

Duloxetine-treated patients also experienced greater improvements in their functioning as shown by changes from baseline to endpoint in the SDS global and domain scores (both duloxetine groups vs. placebo, p ≤ .001) (Figure 2). Duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients experienced a mean decrease of more than 3 points greater than placebo-treated patients in the SDS global functional impairment score, which represents a 47% improvement from baseline for the duloxetine-treated patients. Significant improvements were also seen for the duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated groups across each specific role domain (work, social life, and family/ home management) compared with the placebo-treated patients (both duloxetine groups vs. placebo, all comparisons, p ≤ .001).

Figure 2.

Change From Baseline to Endpoint on the Sheehan Disability Scale Global Functional Impairment and Specific Domain Scores by Treatment Group

There were no significant differences between duloxetine 60 mg− and 120 mg−treated patients on any of the efficacy outcome measures.

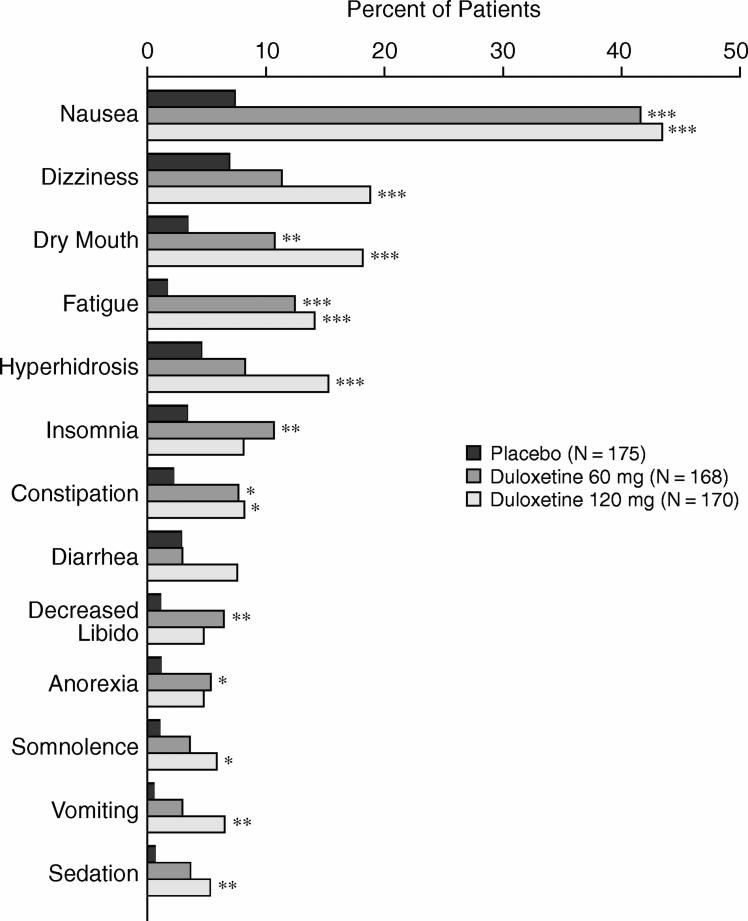

Tolerability

Approximately 20% of duloxetine-treated patients had their dose decreased during the first 2 weeks of acute treatment. Thirteen treatment-emergent adverse events occurred in the duloxetine groups at a frequency greater than or equal to 5% and twice the rate of the placebo group (Figure 3). There were no significant differences between the duloxetine groups in the frequency of specific treatment-emergent adverse events. Overall, nausea was the most frequent event. Within the duloxetine 60 mg group, nausea was reported as mild by 13.7%, moderate by 23.2%, and severe by 4.8%. Similarly, 14.1%, 22.4%, and 7.1% of patients treated with duloxetine 120 mg reported mild, moderate, and severe nausea, respectively. Among the placebo-treated patients, mild nausea was reported at a rate of 4.0% and moderate nausea at 3.4%. Nausea resulted in study discontinuation for 6.0% of duloxetine 60 mg−treated patients, 2.4% of duloxetine 120 mg−treated patients, and none of the placebo-treated patients, which was a significantly higher rate for the duloxetine 60 mg group compared with placebo group (p ≤ .001). No other specific adverse events resulted in differential discontinuation rates between duloxetine and placebo. There was no significant difference between groups in the frequency of serious adverse events. In the placebo group, 1 patient had a myocardial infarction, and 1 had erysipelas; no serious adverse events occurred in the duloxetine groups.

Figure 3.

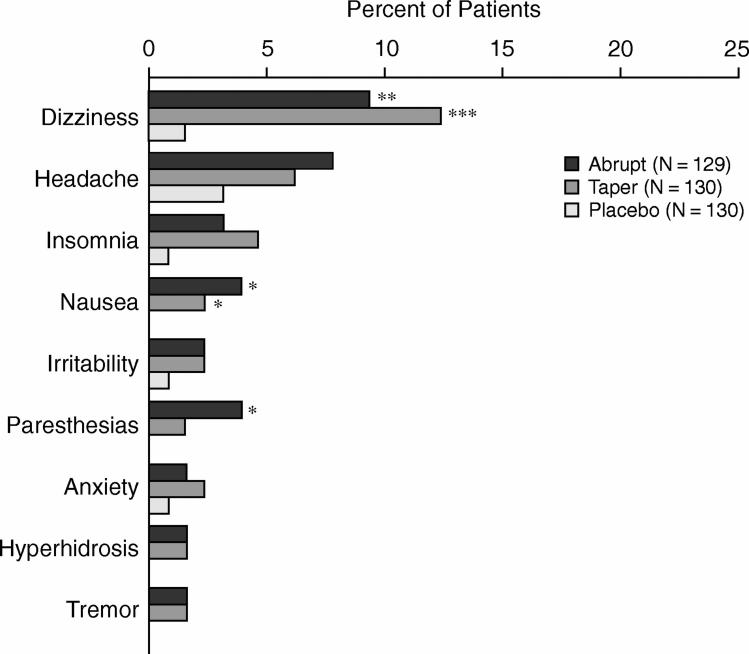

Adverse Events That Had an Incidence ≥ 5% for Duloxetine and Were at Least Twice as Frequent as for Placebo

During the discontinuation phase, 31.1% of the duloxetine 60 mg−treated patients and 29.8% of the duloxetine 120 mg−treated patients experienced 1 or more discontinuation-emergent adverse events (DEAEs) compared with 16.2% for placebo-treated patients (overall p ≤ .05). Dizziness was the most frequently experienced DEAE. Among those who were discontinued abruptly, dizziness occurred in 9.9% of the duloxetine 60 mg−treated patients and 8.6% of the duloxetine 120 mg−treated patients compared with 1.5% of the placebo-treated patients (duloxetine vs. placebo, both comparisons, p ≤ .05). In the medication taper group, dizziness rates were 14.1% of duloxetine 60 mg−treated patients and 10.6% of duloxetine 120 mg−treated patients (duloxetine 60 mg vs. placebo, p ≤ .001; duloxetine 120 mg vs. placebo, p ≤ .01). In addition, nausea occurred significantly more frequently as a DEAE for the duloxetine 60 mg group compared with the placebo group (p ≤ .05). Overall, duloxetine patients did not experience significantly greater rates of DEAEs if discontinuation occurred abruptly or with a gradual taper (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Discontinuation-Emergent Adverse Events During Drug-Tapering Phase

DISCUSSION

The results of this double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study indicate that duloxetine is efficacious and well tolerated for the treatment of GAD. Patients who received duloxetine experienced greater improvement in their anxiety symptom severity and their overall functioning than patients who received placebo. These improvements were clinically meaningful as indicated by greater response, sustained improvement, and remission rates at study endpoint. Within the context of 9 weeks of acute treatment, the finding that approximately 30% to 40% of the duloxetine-treated patients met criteria for remission at study endpoint is particularly encouraging.

Not only did patients who received duloxetine improve more on their overall symptom severity than patients who received placebo, but they also experienced significant reductions in both the psychic and somatic components of their illness as shown by the HAM-A factor scores. At a symptom level, duloxetine-treated patients experienced greater improvement in anxious mood, tension, fears, difficulty concentrating, muscular pain, cardiovascular, respiratory symptoms, and anxiety behaviors compared with placebo-treated patients. The improvement in somatic symptoms associated with GAD is particularly relevant for the primary care setting, where 87% of patients with GAD have presenting complaints other than anxiety, such as somatic illness, pain, depression, and sleep disturbances.5

Patients with GAD are more likely to present with somatic types of symptoms compared with other primary care patients.5 In a large survey of primary care patients in Belgium, patients with GAD and/or depression most frequently presented with otorhinolaryngologic, cardiovascular, respiratory, and rheumatologic symptoms as the reason for their visit.6 Although these studies cannot address the underlying source of these presenting complaints, they do suggest that physical symptoms are an area of significant concern for patients with GAD, and these types of symptoms often overlap with the somatic manifestations of GAD.7 Thus, the finding that duloxetine treatment was effective in reducing some of the somatic symptoms associated with GAD may help to break the cycle between worry and physical complaints.

Duloxetine treatment also enhanced patients' overall functioning compared with placebo treatment. On the Sheehan Disability Scale, duloxetine-treated patients had significantly greater improvements compared with placebo-treated patients across all role domains, including their work, social life, and management of home and family responsibilities. The finding of greater improvements in functioning was also reflected by the global scores, in which duloxetine-treated patients were rated as more improved than placebo-treated patients by both clinician and self-report. The impact of treatment on functioning may have implications for long-term outcomes. In the Primary Care Anxiety Project,32 135 patients with GAD were followed for a 2-year period. Within this sample, lower psychosocial impairment was a significant predictor of recovery from GAD.

Both duloxetine 60 mg and duloxetine 120 mg were well tolerated as indicated by the low study discontinuation rate due to adverse events, which did not differ between dose groups. Twenty percent of patients in the duloxetine group were initially lowered from their 60-mg dose due to tolerability, but they were then increased to their randomly assigned dose over a 2-week period. Overall, duloxetine-treated patients experienced greater frequency of treatment-emergent adverse events compared with placebo-treated patients, but other than nausea, there were no specific adverse events that resulted in differential rates of study discontinuation. Most patients who experienced nausea were able to tolerate it, as only 2.7% of the entire sample discontinued from the study due to nausea. Within this study, patients did not demonstrate a differential rate in adverse events associated with medication discontinuation based on the method of abrupt or gradual tapering. Dizziness was the symptom most likely to emerge during medication discontinuation.

The strengths of the present study include its geographical diversity and a number of methodological innovations. The primary outcome measure (HAM-A) was independent of the entry criterion (HADS anxiety subscale), which allows for a more normal distribution of HAM-A scores at baseline. In addition, because the HADS anxiety subscale severity was used as the entry criterion, the HAM-A score at baseline was less likely to be affected by the score inflation that may occur in order to meet the inclusion criteria. Further, the HAM-A ratings were administered using the SIGH-A version, which has been shown to enhance the reliability of the interview.19 Also, the training of the raters for both style and scoring using the Rater Applied Performance Scale assessment tool may have improved concordance among the sites.

The findings of the present study should be considered within the following limitations. The double-blind portion of the study was 9 weeks in length, therefore these findings generalize only to short-term treatment. Longer trials will be needed to assess efficacy, safety, and tolerability of maintenance duloxetine treatment for GAD. The study did not include an active comparator, so direct comparisons cannot be made between duloxetine and other medications for the treatment of GAD. Finally, GAD is often comorbid with depression and other anxiety disorders.33 As the present study excluded patients with significant comorbidities, the response of the comorbid condition to duloxetine would require additional study.

One of the primary challenges for patients with GAD is access to empirically validated, evidence-based treatment interventions.34,35 Within the primary care setting, there is a paucity of studies examining treatment interventions and outcomes for the GAD population. Although the present study was not conducted at primary care medical settings, there is evidence to support the generalizability of the sample. In a large primary care survey, 288 patients with GAD, determined by the Primary Care Evaluation for Mental Disorders36 instrument, were administered the SIGH-A by telephone.37 The survey found that 59% of these patients had a HAM-A total score ≥ 14. Also, patients in the primary care setting are more likely to meet the diagnosis for “pure” GAD, whereas patients in psychiatric settings are more likely to have comorbid depression or anxiety.38 As noted above, in this study, significant diagnostic comorbidity was an exclusion criterion.

In summary, duloxetine 60 mg/day and duloxetine 120 mg/day were efficacious and well tolerated in the treatment of GAD. Across both psychic and somatic symptoms, duloxetine was efficacious in reducing symptom severity, and the treatment enhanced patients' role functioning. SSRI and SNRI medications such as escitalopram, sertraline, paroxetine, and venlafaxine have demonstrated efficacy for the treatment of GAD.9 The findings of the present study support the inclusion of duloxetine as an empirically validated pharmacologic intervention for GAD as well.

Drug names: duloxetine (Cymbalta), escitalopram (Lexapro and others), fluoxetine (Prozac and others), paroxetine (Paxil, Pexeva, and others), sertraline (Zoloft and others), venlafaxine (Effexor and others).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients who agreed to participate in this clinical trial as well as the clinical staff and principal investigators involved in this global study, including H. Naukkarinen, M.D.; U. Lepola, M.D.; G. Joffe, M.D.; L. Lahdelma, M.D.; R. Jokinen, M.D.; J. Seppala, M.D.; M. Sorvaniemi, M.D.; O. P. Mehtonen, M.D.; J. Penttinen, M.D.; A. Ahokas, M.D.; B. Jomard, M.D.; D. Bonnaffoux, M.D.; O. Bourgeouis-Adragna, M.D.; P. Khalifa, M.D.; M. Beyadh, M.D.; B. Bergholdt, M.D.; P. Franz, M.D.; J. Thomsen, M.D.; B. Gerstwitz, M.D.; J. De la Torre, M.D.; A. L. Montejo, M.D.; L. De Angel, M.D.; A. Morinigo, M.D.; J. Bobes, M.D.; K. Wahlstedt, M.D.; L. Gelius, M.D.; N. G. Lindgren, M.D.; L. Ostling, M.D.; P. Ekdahl, M.D.; N. El-Khalili, M.D.; and J. Hartford, M.D. The authors also thank the Duloxetine Antidepressant Team for their excellent implementation of this trial.

Footnotes

The research was supported by Eli Lilly and Co. and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Acknowledgments are listed at the end of the article.

Dr. Koponen has received honoraria from or participated in speakers bureaus for AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, H. Lundbeck, Janssen-Cilag, and Organon. Dr. Allgulander has served as a consultant or speaker for Eli Lilly, H. Lundbeck, Pfizer, and Wyeth. Drs. Erickson, Detke, Ball, and Russell are employees and/or shareholders of Eli Lilly. Drs. Dunayevich and Pritchett were previously employees and shareholders of Eli Lilly.

REFERENCES CITED

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- Rickels K, Rynn MA.. What is generalized anxiety disorder? J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:4–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn-Saric R.. Psychic and somatic anxiety: worries, somatic symptoms and physiological changes. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1998;393:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb05964.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker ES, Goodwin R, and Holting C. et al. Content of worry in the community: what do people with generalized anxiety disorder or other disorders worry about? J Nerv Ment Dis. 2003 191:688–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, and Beesdo K. et al. Generalized anxiety and depression in primary care: prevalence, recognition, and management. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63:24–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ansseau M, Fischler B, and Dietrick M. et al. Prevalence and impact of generalized anxiety disorder and major depression in primary care in Belgium and Luxemburg: the GADIS study. Eur Psychiatry. 2005 20:229–235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoehn-Saric R.. Generalized anxiety disorder in medical practice. Prim Psychiatry. 2005;12:30–34. [Google Scholar]

- Nutt DJ, Ballenger JC, and Sheehan D. et al. Generalized anxiety disorder: comorbidity, comparative biology and treatment. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002 5:315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman WK. Selecting pharmacotherapy for generalized anxiety disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004 65suppl 13. 8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollack MH.. Optimizing pharmacotherapy of generalized anxiety disorder to achieve remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:20–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allgulander C, Bandelow B, and Hollander E. et al. WCA recommendations for the long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder. CNS Spectrums. 2004 8suppl 1. 53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Davidson JR, and Lecrubier Y. et al. Consensus statement on generalized anxiety disorder from the International Consensus Group on Depression and Anxiety. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001 62:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Detke MJ, Lu Y, and Goldstein DJ. et al. Duloxetine, 60 mg once daily, for major depressive disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63:308–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein DJ, Lu Y, and Detke MJ. et al. Duloxetine vs placebo in patients with painful diabetic neuropathy. Pain. 2005 116:109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M.. Development of a rating scale for primary depressive illness. Br J Soc Clin Psychol. 1967;6:278–296. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8260.1967.tb00530.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunner DL, Goldstein DJ, and Mallinckrodt C. et al. Duloxetine in treatment of anxiety symptoms associated with depression. Depress Anxiety. 2003 18:53–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trolesen KB, Nielson EO, Mirza NR.. Chronic treatment with duloxetine is necessary for an anxiolytic-like response in the mouse zero maze: the role of the serotonin transporter. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:741–750. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, Lecrubier Y, and Sheehan KH. et al. The MINI-International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-IV. J Clin Psychiatry. 1998 59suppl 20. 34–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shear MK, Vander Bilt J, and Rucci P. et al. Reliability and validity of a structured interview guide for the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (SIGH-A). Depress Anxiety. 2001 13:166–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipsitz J, Kobak K, and Feiger A. et al. The Rater Applied Performance Scale: development and reliability. Psychiatry Res. 2004 127:147–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lipman RS, Covi L, and Downing RW. et al. Pharmacotherapy of anxiety and depression: rationale and study design. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1981 17:91–94. [Google Scholar]

- Raskin A, Schulterbrandt J, and Reatig N. et al. Replication of factors of psychopathology in interview, ward behavior and self-report ratings of hospitalized depressives. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1969 148:87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Medical Association. Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. First adopted in 1964; most recent revision in 2000. Available at: http://www.wma.net/e/policy/b3.htm. Accessibility verified January 12, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton M.. The assessment of anxiety states by rating. Br J Med Psychol. 1959;32:50–55. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8341.1959.tb00467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP.. The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1983;67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. The clinician global severity and impression scales. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Dept Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM) 76-338. Rockville, Md: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- Guy W. The patient's global impression and severity scale. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. US Dept Health, Education, and Welfare publication (ADM) 76–338. Rockville, Md: National Institute of Mental Health; 1976 [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV. The Anxiety Disease. New York, NY: Charles Scribner and Sons. 1983 [Google Scholar]

- DeLoach LJ, Higgins MS, and Caplan AB. et al. The visual analog scale in the immediate post-operative period: intrasubject variability and correlation with a numeric scale. Anesth Analg. 1998 86:102–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malllinckrodt CH, Kaiser CJ, and Watkin JG. et al. The effect of correlation structure on treatment contrasts estimated from incomplete clinical trial data with likelihood-based repeated measures compared with the last observation carried forward ANOVA. Clin Trials. 2004 1:477–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doyle AC, Pollack MH. Establishment of remission criteria for anxiety disorders. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003 64suppl 15. 40–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez BF, Weisberg RB, and Pagano ME. et al. Characteristics and predictors of full and partial recovery from generalized anxiety disorder in primary care patients. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006 194:91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Chiu WT, and Demler O. et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 62:617–627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, Kessler RC.. Recent care of common mental disorders in the United States: prevalence and conformance with evidence-based recommendations. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:284–292. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.9908044.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang PS, Berglund P, and Olfson M. et al. Failure and delay in initial treatment contact after first onset of mental disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005 62:603–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JBW, and Kroenke K. et al. Primary Care Evaluation of Mental Disorders (PRIME-MD). In: Rush AJ, Pincus HA, First MB, et al, eds. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Spitzer RL, Williams JB, and Kroenke K. et al. Utility of a new procedure for diagnosing mental disorders in primary care: the PRIME-MD 1000 study. JAMA. 1994 272:1749–1756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Wittchen HU. Patterns and correlates of generalized anxiety disorder in community samples. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002 63suppl 8. 4–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]