Abstract

Every year, thirty thousand people worldwide are diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). T1DM, also called autoimmune diabetes, is a multifactorial disease affecting predisposed individuals and involving genetic susceptibilities, environmental triggers, as well as unbalanced immune responses. Auto-reactive T cells, produced during the pathogenesis, play an important role by specifically destroying the pancreatic insulin-producing beta-cells in the islets of Langerhans. Numerous therapeutic interventions have been tested, mostly in animal models, but also in humans. To date, only three phase II/III clinical trials have demonstrated safety and efficacy: anti-CD3 antibody, DiaPep277, and GAD65 (in patients with latent autoimmune diabetes in adults). Unfortunately, a significant number of patients did not respond positively and remained insulin-dependant after completion of therapy. Several reasons account for this. Firstly, the severity of the disease as well as the auto-aggressive T cell repertoire vary from patient to patient leading to a broad range of therapeutic efficacies, and secondly at the time of the treatment the number of remaining beta-cells will directly impact the level of insulin production post-treatment. In this review, we will provide some clues to enhance efficacy of future immuno-interventions in patients with T1DM. We suggest that combination therapies might be the best approach.

Keywords: Autoimmunity, type 1 diabetes, immuno-intervention, combination therapy

Take-home messages

After new-onset diabetes, immuno-interventions have to be given as early as possible to be fully efficacious and increase the odds of permanent remission.

Well-thought out combination therapies will increase efficacy as compared to mono-therapies.

If realized, in-vivo antigen-specific expansion of regulatory T cells in humans could induce long-term remission without adverse side effects.

If an immuno-intervention is given late after new-onset and/or when few beta-cells remain in the pancreas, an efficient combination therapy should include either compounds promoting beta-cell regeneration or islet transplantation.

HLA class II dimers combining antigenic specificity (such as antigenic immunizations) and an immediate bio-availability (such as antibodies) could be an attractive antigen-specific therapy.

1. Introduction

Type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) is one of the most common autoimmune diseases with several million people already affected around the globe. T1DM can occur at any age, but is most commonly diagnosed from infancy to the late thirties. Similarly to other autoimmune diseases, the aetiology of T1DM remains obscure but develops on a genetically susceptible background and also involves a variety of factors, ranging from immune dysregulation to environmental triggers. The outcome is the production of auto-antibodies (aAbs) as well as an expansion of auto-aggressive T cells. Insulin, glutamic acid decarboxylase of 65kDa (GAD65) and islet associated antigen (IA-2 or ICA512) are three major auto-antigens (aAgs) known to be targeted by both the humoral and cellular immune responses. Even though etiological studies have not been able to determine with certainty the causative event(s) triggering T1DM, they have revealed some major mechanisms involved in the pathogenesis. On one hand, aAbs directed against these aAgs are detected during the pre-diabetic phase. They constitute excellent prognostic markers and play a role in the pathogenesis, by capturing and presenting autoantigenic determinants to auto-reactive T cells. On the other hand, activated auto-aggressive T cells are capable of direct cytotoxicity and thus destroy the insulin-producing beta-cells.

Although a remarkable number of therapies, probably more than two hundred have effectively treated T1DM in animal models [1], few of them have been tested in humans. Two major concerns can be put forward to explain such a discrepancy. Firstly, several pre-clinical protocols that have been developed in rodents would be unacceptable in humans due to unethical practices or the possibility of strong side effects. Secondly, the necessary financial support to undertake clinical trials is always difficult to obtain [2]. However, some conclusions can be drawn from the first clinical immuno-interventions and should help us in designing future successful trials.

2. Clinical trials in type 1 diabetes: where do we stand and what did we learn?

So far, a dozen clinical trials have been completed with various successes and failures (Table 1). While some attempted to prevent T1DM by treating susceptible individuals before onset with human insulin or nicotinamide [3,4], others have been conducted to preserve beta-cell mass in newly diagnosed type 1 diabetics by using systemic immune-modulators (cyclosporine A, non-Fc binding anti-CD3 and DiaPep277) or antigen-specific therapies (insulin, GAD65 and altered peptide ligand derived from the insulin B9-23) [5–11]. Three positive outcomes have been reported with anti-CD3, Diapep277 and GAD65 treatments. One of the most striking observations is that efficacy was observed in trials where the drug was administered after recent-onset. Thus, although we possess powerful tools to predict development of T1DM, relying on serum auto-antibodies measurements, we are unable to prevent or delay diabetes onset. It is worth noting that (1) the therapies showing the most robust preservation of C-peptide levels over time are systemic immune modulators without antigenic specificity and (2) the maximum efficacy is usually observed in patients with the highest beta-cell mass at trial entry as well as a slower decline in the pancreatic function [10,11]. Importantly, none of the 87 patients enrolled in those ‘successful’ trials has achieved euglycemia so far. In addition, permanent tolerance to beta-cell aAgs has not been obtained in humans and we are still seeking a therapy that would retain long term efficacy (ideally permanent remission), by preventing any relapse without repetitive treatment.

Table 1.

Major clinical trials in type 1 diabetes.

| Administration | Trial | Compound | Efficacy | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Before onset diabetes (prevention trials) | European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT) | Nicotinamide | No effect | [4] |

| Deutsche Nicotinamide Intervention Study (DENIS) | Nicotinamide | No effect | [38] | |

| Diabetes Prevention Trial-Type 1 (DPT-1) | Parenteral Insulin | No effect | [3] | |

| Type 1 Diabetes Prediction and Prevention Study (DIPP) | Nasal insulin | No effect | [39] | |

| Australian phase I nasal insulin trial | Nasal insulin | Decrease in T-cell responses to insulin but no effect on diabetes prevention | [40] | |

|

| ||||

| After new-onset diabetes | Canadian/European CsA trial | Cyclosporin A | Preservation of C-peptide only during drug administration | [6] |

| IMDIAB VII | Oral insulin | No effect | [7] | |

| GAD65 (DIAMYD) | Human GAD65 | 24-weeks positive effect in LADAa patients | [8] | |

| DiaPep277 | Hsp60b immunodominant peptide (residues 437–460) | 1-year positive effect (preservation of C-peptide concentration) | [9] | |

| Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (American trial) | hOKT3γ1(Ala-Ala) – mutated human anti-CD3 | 24-months positive effect on C-peptide levels (transient remission) | [10] | |

| Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 monoclonal antibody (European trial) | ChAglyCD3 – aglycosylated human anti-CD3 | 18-months positive effect seen in patients with the highest C-peptide levels at entry (≥50th percentile) | [11] | |

| NBI-6024 (Neurocrine) | Altered peptide ligand insulin B9-23 (A16,19) | Ongoing | [5] | |

Latent Autoimmune Diabetes in Adults (LADA).

Heat-shock protein-60 (Hsp60).

3. Monotherapies in type 1 diabetes

3.1. Systemic immune modulators

3.1.1. Antibodies

A panel of monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies has been developed and tested in rodents for their anti-diabetogenic capacity. Polyclonal anti-lymphocyte antisera (ALS) as well as anti-CD3 or anti-CD4 monoclonal antibodies (mAb) are the only antibody therapies to date that have cured early diabetic disease in murine models for T1DM [12–14]. They all share the same ability to induce transient lymphodepletion lasting from a couple of days to a couple of weeks after treatment has ended. ALS and anti-CD4 antibodies are strong immune suppressors and principally act by depleting the autoaggressive T cells to restore euglycemia. In contrast, anti-CD3 mAb could be classified as an immune modulator and, thanks to its remarkable properties, constitutes today one of the most attractive therapies for T1DM.

Anti-CD3 immuno-intervention was initially discovered by the laboratory of Bach and Chatenoud who used it for the prevention of organ allograft rejection or in the treatment of T1DM in the NOD model. Thereafter, it was developed for clinical use by the laboratories of Bluestone and Herold [10,14]. For mice, this mAb is produced as an engineered F(ab’)2 fragment of the hamster anti-CD3 monoclonal mAb (145 2C11). For humans, a full humanized IgG1 with a mutated (hOKT3gamma1[Ala-Ala]) or aglycosylated (ChAglyCD3) Fc region that prevents them from binding to the Fc receptors has been developed (Table 1). Treatment with these anti-CD3 mAbs has two important features: First, it is effective in already diabetic animal models and can reverse the course of disease [14,15]. It was therefore given to recent-onset diabetics in two clinical trials, where over the first two years a positive effect on C-peptide levels was observed indicating increased preservation of remaining beta-cell mass. However, in this study long-term tolerance was not achieved [10,11]. Second, as first indicated from studies in the NOD mouse, non-Fc binding anti-CD3 not only affects already committed auto-aggressive effector lymphocytes but also augments regulatory T cells. As demonstrated by Chatenoud and colleagues in the NOD model, they are CD4+CD25+CD62L+ and require most likely TGF-β to mediate durable regression of overt diabetes [16]. In humans, the level of suppressor CD8+CD25+ T cells is up-regulated after anti-CD3 [17]. Interestingly, ex vivo production of IL-5 and IL-10 is significantly increased in the sera of patients treated with hOKT3gamma1[Ala-Ala] while low levels of TNF-α, IL-2 and IL-6 were also detected [18]. Taken together all these data argue that anti-CD3 mAb induces cytokine-mediated regulation both in the murine models and in humans.

3.1.2. Cytokines

Therapeutic protocols involving systemic cytokine administration have been contemplated for many years to treat T1DM. So far, a broad spectrum of efficacy and side effects has been described following cytokine-based therapies in animal models. A variety of TH1 as well as TH2 cytokines have been employed in vivo either to decrease the pool of autoaggressive T cells (usually obtained with TH1 cytokines) or to help in the expansion of Tregs (commonly realized with TH2 cytokines). The most striking observation is that the administration of a vast majority of these cytokines revealed a dual effect depending on (1) the timing of administration, (2) the dose and (3) the route of administration of soluble cytokine or the site of expression in the case of transgenic models. For example, in a transgenic model expressing TNF-α under the control of a tetracycline-inducible promoter, Christen et al. showed that islet-specific TNF-α expression abrogates the ongoing autoimmune process when induced late but not early during pathogenesis [19]. A similar observation was made with the IL-18 cytokine. When administered early (at 4-week old) in the NOD mice, IL-18 plays a promoting role as an enhancer of TH1-type immune responses in diabetes development [20]. On the contrary, when injected systemically late in the disease process into 10-week old NOD mice, IL-18 suppresses autoimmune diabetes by targeting the TH1/TH2 balance of inflammatory immune reactivity in the pancreas [21]. However, we cannot definitely rule out that various systemic levels of IL-18, engendered by two different routes of administration (DNA vaccine encoding IL-18 [20] versus systemic injection of the purified protein [21]), may account for the inconsistent therapeutic outcomes observed. Lastly, local (organ-specific) versus systemic expression of a particular cytokine may impair drastically any anti-diabetogenic effect. For instance, IL-10 expression in the islets of Langerhans promotes diabetes whilst a low systemic dose of this cytokine obtained by using a DNA vaccine resulted in a partial prevention of the disease [22]. All together, these data highlight the complexity of using cytokines alone as immuno-intervention.

3.1.3. DiaPep277

This peptide derived from the heat-shock protein (hsp60) immunodominant epitope within the amino acid residues 437–460 (p277) preserved endogenous insulin production after a randomized, double-blind, phase II trial in some newly diagnosed T1DM patients [9]. Although the mechanism by which the DiaPep277 functions is not completely understood, it is thought that hsp60 activates T cells via the Toll-like receptor 2 [23]. This pathway could also induce the shift from TH1 to TH2 cytokines observed in humans. Thus, this mode of action would categorize DiaPep277 as a systemic rather than an antigen-specific immune modulator. Indeed, so far, no DiaPep277-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs) have been characterized.

3.2. Antigen-specific induction of regulatory T cells in type 1 diabetes

The antigen-specific prevention of T1DM can be achieved in several ways in animals models, (i) with DNA vaccines [24], (ii) with peptide derived from islets antigens [25] or (iii) with full-length islets proteins [26]. Protection is mediated by islet-specific CD4+ Tregs that can protect prediabetic recipients upon adoptive transfer. Several laboratories provided evidence that such antigen-specific Tregs with beneficial effector functions act in vivo by selectively proliferating in the pancreatic draining lymph node (where islet antigens are being presented as aAgs during diabetes development). There, they suppress expansion and activation of autoaggressive T cells, most likely via modulation of antigen-presenting cells [27]. The intriguing and attractive aspect about this type of intervention is that it acts antigen-specifically and therefore locally, avoiding systemic side-effects. Protection from diabetes is sustained and does not require repeated antigenic injections. However, there are several issues that require clinical attention: First, not all islet antigens are equally suited for inducing protection [28]. Second, although not observed under regular experimental conditions so far in T1DM, it is conceivable that immunization with an aAg might accelerate disease as reported in multiple sclerosis [29]. Lastly, such immune interventions in humans have been relatively unfruitful and only one vaccine (human GAD65 full protein) resulted in a 24-week positive effect in LADA (latent autoimmune diabetes in adults) patients that display slow onset of diabetes (Table 1).

3.3. Compounds stimulating beta-cell proliferation/regeneration

Clinical symptoms of T1DM generally occur when approximately 80% of the beta-cells have been destroyed. Such an observation opens up the possibility to grow new beta-cell from this remaining beta-cell mass (or from other progenitor cells) at the onset of diabetes onset to restore normoglycemia. Therefore, there has been a growing interest in the development of compounds that stimulate beta-cell regeneration. Hormones, such as epidermal growth factor (EGF) or beta-cellulin (a member of the EGF family) have been extensively studied. Their systemic administration was shown to improve beta-cell regeneration in 90% pancreatectomized rats [30]. In a similar model, other biomolecules also revealed some regenerative capacities. Among them, the most famous are the glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), or its long-lasting agonist exendin-4, that stimulate pancreatic regeneration and beta-cell expansion through two processes: neogenesis of progenitor cells and proliferation or replication of mature beta-cells [31]. However, unless the immune response that attacks beta-cells can be dampened, regenerative compounds might not be able to expand enough beta-cells to permanently maintain normoglycemia.

4. Combination therapies to enhance efficacy

After several attempts to develop potent immuno-interventions to cure T1DM it seems that a monotherapy will not reach the necessary efficacy in many cases. The genetic and pathologic heterogeneities (beta cell mass, number and specificity of auto-reactive T cells, etc…) from patient to patient at trial entry make the discovery of one therapeutic approach that will be efficacious and safe when administered into all patients extremely difficult. To overcome this problem and to enhance efficacy, we propose to use combination therapies and adapt them to the residual beta-cell mass at trial entry after new-onset of diabetes (Table 2). Two major goals have to be accomplished: (1) the rapid blockade of the immune system and dampening of any auto-reactive responses without strong side-effects and (2) the regeneration of a critical beta-cell mass in order to maintain euglycemia without repetitive insulin injections.

Table 2.

Adapting the combination therapy to the residual beta-cell mass at trial entry after new-onset diabetes.

| C-peptide range at entry (nmol/l) | Approximate residual beta-cell mass (% of total beta-cell mass)a | Therapy to be contemplated at trial entry | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Affecting the immune system | Affecting insulin secretion | ||

| > 0.5 | > 15 |

1-Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 + antigenic immunizations.

2-HLA class II dimers. |

May not be needed. Based on anti-CD3 trials, insulin needs decreased over the first 6 months in patients with a C-peptide level at entry ≥50th percentile (“natural” beta-cell regeneration?) |

| 0.5 – 0.2 | 15 – 5 |

1-Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 + antigenic immunizations.

2-HLA class II dimers. |

Regenerative compounds (GLP-1, Exendin-4, EGF, gastrin or others) |

| < 0.2 | < 5 |

1-Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 + antigenic immunizations.

2-HLA class II dimers. |

Pancreatic islet transplant |

May differ from patient to patient.

4.1. Dampening the auto-aggressive responses

We believe that this constitutes the first step that needs to be realized in order to maintain permanent tolerance to islet-aAgs. While many therapies have been successful in animal models none of those tested in humans have yet reached the ultimate goal. To progress, we will have to use compounds that combine a rapid (to stop beta-cell decline) and antigen-specific (to avoid strong side-effects) mode of action.

4.1.1. Non-Fc binding anti-CD3 and islet-antigen immunization

Anti-CD3 constitutes an extraordinary systemic immune-modulator that has showed repetitive efficacies even when injected at relatively low doses after new-onset of T1DM (see paragraph 3.1.1). Short-term anti-CD3 therapy exerts its effects by promoting a milieu for generation of CD4+CD25+ Treg, however it is conceivable that only a small number of these Tregs are islet antigen-specific. This probably impacts the effectiveness of the treatment and the induction of increased numbers of islet-specific Tregs will augment the odds for a permanent remission from diabetes. Therefore, we hypothesized that combining systemic anti-CD3 with islet-aAgs immunization might synergize and expand islet-specific Tregs that will be recruited to the site of inflammation in the pancreas or the pancreatic lymph nodes (PLNs), where they will suppress the auto-aggressive attack (Figure 1). Our recent data showed that among several aAgs tested, a proinsulin peptide (B24–C36) administered intranasally with low a dose of anti-CD3 synergized to cure T1DM after new-onset in two animal models [28]. The induced proinsulin-specific Tregs produced regulatory cytokines (IL-10 and TGF-β) and migrated to the PLNs to block auto-reactive CD8+ T cells by bystander suppression. This approach constitutes a great hope towards the development of safer and more effective immuno-interventions and thus should be tested in humans in the near future. It is worth noting that another immune modulator without strong side effects such as Diapep277 might be also a good candidate to combine with islet-aAgs immunization.

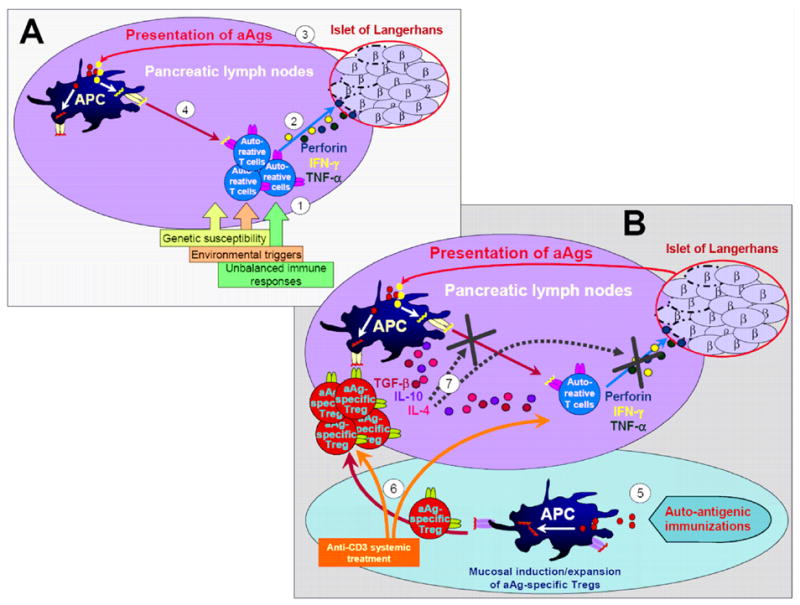

Figure 1. Combination therapy of anti-CD3 antibody and auto-antigenic immunizations efficiently dampens the auto-aggressive responses.

A. Pathogenesis of type 1 diabetes. (1) In susceptible individuals, environmental triggers together with unbalanced immune responses cause the priming of auto-reactive effector T cells. (2) Auto-aggressive T cells infiltrate the islets of Langerhans and start destroying the insulin producing beta-cells via perforin- and cytokine-mediated cytotoxic mechanisms. (3) Auto-antigens (aAgs), such as insulin, GAD65 and others, are presented by antigen-presenting cells (APC) in the pancreatic lymph nodes (PLNs), (4) which enable the expansion of effector T cells and initiate epitope spreading. B. Blockade of type 1 diabetes by in-vivo expansion of antigen-specific regulatory T cells. (5) Immunization with various aAgs via a tolerogenic route (i.e mucosal) has been successful in inducing aAg-specific regulatory T cells (Tregs). (6) Systemic treatment with non-Fc binding anti-CD3 creates a therapeutic window by promoting a milieu for expansion of Tregs and by depletion of auto-reactive T cells. (7) Expanded aAg-specific Tregs migrate into the PLNs and dampen the auto-aggressive responses by bystander suppressive mechanisms.

4.1.2. MHC/HLA Class II multimers

These agents have become one of the most appealing future therapies for the treatment of autoimmune diseases. The fact that they carry at the same time the antigenic specificity (binding to the targeted T-cell receptor [TCR]), and an immediate bio-availability (such as antibodies) is of great interest and might accomplish permanent remission of T1DM in an antigen-specific manner [32]. Successful interventions with peptide-MHC (pMHC) multimers have been reported in animal models for T1DM [33]. By targeting a specific T cell population, pMHC are capable of either activating Treg cells or inducing anergy of auto-aggressive CD4+ T cells. Both of these mechanisms have been observed [33]. Furthermore, this tool could also be used to grow antigen-specific Tregs in vitro that could then be re-injected into newly-diagnosed individuals [34]. Two main issues have to be overcome for future translation into humans: First, the CD4+ population to be targeted has to be rigorously chosen to avoid any exacerbation of the disease and second the methods of production have to be safer (to be injectable into humans), more cost-effective and flexible (to examine a broad varieties of epitopes).

4.2. Realizing the regeneration of beta-cell mass

Although potent immune-therapies are being developed and tested in humans, we believe that some patients will never regain enough pancreatic function to sustain normoglycemia. In fact, after recent-onset diabetes, patients differ in regard to their beta-cell mass (Table 2). It is therefore doubtful that all type 1 diabetics will profit equally from the same combination therapy. If the treatment is started early enough in patients with a C-peptide level at entry ≥ 50th percentile, regenerative compounds might not be needed as observed in the European anti-CD3 clinical trial [11]. This points out that “natural” beta-cell regeneration might exist. On the other hand, islet neogenesis therapy will be necessary when the beta-cell mass drops below a critical threshold (C-peptide level inferior to 0.5 nmol/l). So far, a mixture of EGF and gastrin showed the best regenerative capacity in vitro as well as in vivo with murine and human beta-cells [35,36]. Finally, synergy between a systemic immunomodulator and regenerative compounds might be the optimal treatment in diabetic patients with low beta-cell mass at trial entry, as observed in the NOD model when ALS and exendin-4 were combined [37]. If the C-peptide level is extremely low (less than 0.2 nmol/l), the only option could be an islet-transplantation in conjunction with safe and efficient immune-modulators (Table 2).

5. Concluding remarks

By ‘freezing’ the auto-aggressive responses in recent-onset diabetes and maybe other autoimmune disorders, by combining antigen-specific induction of Tregs with a suitable systemically acting drug such as anti-CD3, one can expect several advantages. Efficacy is enhanced, the risk for side effects is reduced and the need to further increase the systemic drug is obviated. This will allow for the establishment of an antigen-specific therapy that should be a central component when realizing the goal of long-term tolerance, because Tregs can exert bystander suppression and act site-specifically wherever their cognate aAg is expressed. For patients with the lowest C-peptide levels at trial entry, a component promoting beta-cell regeneration should be added. Ultimately, to meet the ideal criteria, a well-balanced therapy should combine an antigen-specific blockade of auto-aggressive T cell responses with a chemical or surgical restoration of normoglycemia.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Eleanor Ling for critically reading the manuscript. This work is supported by NIH grants AI51973 and DK51091 to M.G.V.H. and D.B. is recipient of a Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation Postdoctoral Fellowship (2004–2005) and a European Marie-Curie Outgoing Fellowship (2005–2008).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Roep BO, et al. Satisfaction (not) guaranteed: re-evaluating the use of animal models of type 1 diabetes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4 (12):989–997. doi: 10.1038/nri1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.von Herrath MG, Nepom GT. Lost in translation: barriers to implementing clinical immunotherapeutics for autoimmunity. J Exp Med. 2005;202 (9):1159–1162. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pozzilli P. The DPT-1 trial: a negative result with lessons for future type 1 diabetes prevention. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2002;18 (4):257–259. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gale EA, et al. European Nicotinamide Diabetes Intervention Trial (ENDIT): a randomised controlled trial of intervention before the onset of type 1 diabetes. Lancet. 2004;363 (9413):925–931. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15786-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alleva DG, et al. Immunological characterization and therapeutic activity of an altered-peptide ligand, NBI-6024, based on the immunodominant type 1 diabetes autoantigen insulin B-chain (9–23) peptide. Diabetes. 2002;51 (7):2126–2134. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.51.7.2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin S, et al. Follow-up of cyclosporin A treatment in type 1 (insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: lack of long-term effects. Diabetologia. 1991;34 (6):429–434. doi: 10.1007/BF00403182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pozzilli P, et al. No effect of oral insulin on residual beta-cell function in recent-onset type I diabetes (the IMDIAB VII). IMDIAB Group. Diabetologia. 2000;43 (8):1000–1004. doi: 10.1007/s001250051482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Agardh CD, et al. Clinical evidence for the safety of GAD65 immunomodulation in adult-onset autoimmune diabetes. J Diabetes Complications. 2005;19 (4):238–246. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2004.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raz I, et al. Beta-cell function in new-onset type 1 diabetes and immunomodulation with a heat-shock protein peptide (DiaPep277): a randomised, double-blind, phase II trial. Lancet. 2001;358 (9295):1749–1753. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06801-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herold KC, et al. A Single Course of Anti-CD3 Monoclonal Antibody hOKT3{gamma}1(Ala-Ala) Results in Improvement in C-Peptide Responses and Clinical Parameters for at Least 2 Years after Onset of Type 1 Diabetes. Diabetes. 2005;54 (6):1763–1769. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.6.1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Keymeulen B, et al. Insulin needs after CD3-antibody therapy in new-onset type 1 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2005;352 (25):2598–2608. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Makhlouf L, et al. Depleting anti-CD4 monoclonal antibody cures new-onset diabetes, prevents recurrent autoimmune diabetes, and delays allograft rejection in nonobese diabetic mice. Transplantation. 2004;77 (7):990–997. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000118410.61419.59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maki T, et al. Long-term abrogation of autoimmune diabetes in nonobese diabetic mice by immunotherapy with anti-lymphocyte serum. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89 (8):3434–3438. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chatenoud L, et al. Anti-CD3 antibody induces long-term remission of overt autoimmunity in nonobese diabetic mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91 (1):123–127. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.von Herrath MG, et al. Nonmitogenic CD3 antibody reverses virally induced (rat insulin promoter-lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus) autoimmune diabetes without impeding viral clearance. J Immunol. 2002;168 (2):933–941. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.2.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Belghith M, et al. TGF-beta-dependent mechanisms mediate restoration of self-tolerance induced by antibodies to CD3 in overt autoimmune diabetes. Nat Med. 2003;9 (9):1202–1208. doi: 10.1038/nm924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bisikirska B, et al. TCR stimulation with modified anti-CD3 mAb expands CD8+ T cell population and induces CD8+CD25+ Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115 (10):2904–2913. doi: 10.1172/JCI23961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herold KC, et al. Activation of human T cells by FcR nonbinding anti-CD3 mAb, hOKT3gamma1(Ala-Ala) J Clin Invest. 2003;111 (3):409–418. doi: 10.1172/JCI16090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Christen U, et al. A dual role for TNF-alpha in type 1 diabetes: islet-specific expression abrogates the ongoing autoimmune process when induced late but not early during pathogenesis. J Immunol. 2001;166 (12):7023–7032. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oikawa Y, et al. Systemic administration of IL-18 promotes diabetes development in young nonobese diabetic mice. J Immunol. 2003;171 (11):5865–5875. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.5865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothe H, et al. IL-18 inhibits diabetes development in nonobese diabetic mice by counterregulation of Th1-dependent destructive insulitis. J Immunol. 1999;163 (3):1230–1236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang ZL, et al. Intramuscular injection of interleukin-10 plasmid DNA prevented autoimmune diabetes in mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2003;24 (8):751–756. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zanin-Zhorov A, et al. T cells respond to heat shock protein 60 via TLR2: activation of adhesion and inhibition of chemokine receptors. Faseb J. 2003;17 (11):1567–1569. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1139fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.von Herrath MG. Vaccination to prevent type 1 diabetes. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2002;1 (1):25–28. doi: 10.1586/14760584.1.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McDevitt H. Specific antigen vaccination to treat autoimmune disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(Suppl 2):14627–14630. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405235101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Homann D, et al. Insulin in oral immune “tolerance”: a one-amino acid change in the B chain makes the difference. J Immunol. 1999;163 (4):1833–1838. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tang Q, et al. Visualizing regulatory T cell control of autoimmune responses in nonobese diabetic mice. Nat Immunol. 2006;7 (1):83–92. doi: 10.1038/ni1289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bresson D, et al. A novel combination therapy in recent-onset autoimmune diabetes: Synergy of anti-CD3 and nasal proinsulin to induce regulatory T cells. J Clin Invest. 2006 doi: 10.1172/JCI27191. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bielekova B, et al. Encephalitogenic potential of the myelin basic protein peptide (amino acids 83–99) in multiple sclerosis: results of a phase II clinical trial with an altered peptide ligand. Nat Med. 2000;6 (10):1167–1175. doi: 10.1038/80516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li L, et al. Promotion of beta-cell regeneration by betacellulin in ninety percent-pancreatectomized rats. Endocrinology. 2001;142 (12):5379–5385. doi: 10.1210/endo.142.12.8520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.von Herrath M. E1-INT (Transition Therapeutics/Novo Nordisk) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2005;6 (10):1037–1042. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mallone R, Nepom GT. Targeting T lymphocytes for immune monitoring and intervention in autoimmune diabetes. Am J Ther. 2005;12 (6):534–550. doi: 10.1097/01.mjt.0000178772.54396.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Casares S, et al. Down-regulation of diabetogenic CD4+ T cells by a soluble dimeric peptide-MHC class II chimera. Nat Immunol. 2002;3 (4):383–391. doi: 10.1038/ni770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tang Q, et al. In vitro-expanded antigen-specific regulatory T cells suppress autoimmune diabetes. J Exp Med. 2004;199 (11):1455–1465. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Suarez-Pinzon WL, et al. Combination Therapy With Epidermal Growth Factor and Gastrin Increases {beta}-Cell Mass and Reverses Hyperglycemia in Diabetic NOD Mice. Diabetes. 2005;54 (9):2596–2601. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.54.9.2596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Suarez-Pinzon WL, et al. Combination therapy with epidermal growth factor and gastrin induces neogenesis of human islet {beta}-cells from pancreatic duct cells and an increase in functional {beta}-cell mass. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;90 (6):3401–3409. doi: 10.1210/jc.2004-0761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ogawa N, et al. Cure of overt diabetes in NOD mice by transient treatment with anti-lymphocyte serum and exendin-4. Diabetes. 2004;53 (7):1700–1705. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lampeter EF, et al. The Deutsche Nicotinamide Intervention Study: an attempt to prevent type 1 diabetes. DENIS Group. Diabetes. 1998;47 (6):980–984. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.47.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kupila A, et al. Intranasally administered insulin intended for prevention of type 1 diabetes--a safety study in healthy adults. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2003;19 (5):415–420. doi: 10.1002/dmrr.397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrison LC, et al. Pancreatic beta-cell function and immune responses to insulin after administration of intranasal insulin to humans at risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27 (10):2348–2355. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.10.2348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]