Abstract

The newly sequenced genome of Monodelphis domestica not only provides the out-group necessary to better understand our own eutherian lineage, but it enables insights into the innovative biology of metatherians. Here, we compare Monodelphis with Homo sequences from alignments of single nucleotides, genes, and whole chromosomes. Using PhyOP, we have established orthologs in Homo for 82% (15,250) of Monodelphis gene predictions. Those with single orthologs in each species exhibited a high median synonymous substitution rate (dS = 1.02), thereby explaining the relative paucity of aligned regions outside of coding sequences. Orthology assignments were used to construct a synteny map that illustrates the considerable fragmentation of Monodelphis and Homo karyotypes since their therian last common ancestor. Fifteen percent of Monodelphis genes are predicted, from their low divergence at synonymous sites, to have been duplicated in the metatherian lineage. The majority of Monodelphis-specific genes possess predicted roles in chemosensation, reproduction, adaptation to specific diets, and immunity. Using alignments of Monodelphis genes to sequences from either Homo or Trichosurus vulpecula (an Australian marsupial), we show that metatherian X chromosomes have elevated silent substitution rates and high G+C contents in comparison with both metatherian autosomes and eutherian chromosomes. Each of these elevations is also a feature of subtelomeric chromosomal regions. We attribute these observations to high rates of female-specific recombination near the chromosomal ends and within the X chromosome, which act to sustain or increase G+C levels by biased gene conversion. In particular, we propose that the higher G+C content of the Monodelphis X chromosome is a direct consequence of its small size relative to the giant autosomes.

The newly sequenced genome (2n = 18; 3.6 Gb) of the South American gray short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica) (Mikkelsen et al. 2007) allows initial comparisons of its predicted gene set, and its chromosomes, with those of humans. Monodelphis is a metatherian mammal (marsupial) whose lineage split from that of eutherians (placental mammals) ∼170–190 million years ago (Mya) (Kumar and Hedges 1998; Woodburne et al. 2003). Since then, metatherians and eutherians have acquired distinct physiological and behavioral features. However, they still share many ancestral therian characters, most notably lactation using mammary papilla, and the bearing of live young without using a shelled egg.

Monodelphis is a small (80–155 g) and nocturnal marsupial. In the wild, it is terrestrial, present in low population densities, and feeds mainly on invertebrates and small vertebrates (Streilein 1982b). In common with murid rodents, reproduction occurs throughout the year, females enter oestrus following exposure to male odors (Fadem and Rayve 1985), and both sexes rely heavily on pheromonal communication (Streilein 1982a). Unlike murid rodents, however, male animals use skin and glandular secretions rather than urine odors for marking, possibly in order to conserve water, since some populations of Monodelphis are found in semiarid environments (Streilein 1982b; Zuri et al. 2005).

Much of the anatomical, physiological, and behavioral differences between metherian and eutherian mammals may be due to protein coding genes present in lineage-specific duplicates. These genes may either share together the functions of the progenitor (“subfunctionalization”) or have each acquired innovative roles (“neofunctionalization”) (Ohno 1970; Hughes 1994; Lynch and Conery 2000; Lynch and Force 2000). In the genomes of sequenced eutheria, the majority of the protein coding genes that are specific to the human (Homo sapiens), mouse (Mus musculus), or rat (Rattus norvegicus) fall into a few well-defined functional classes (Lander et al. 2001; Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002; Rat Genome Sequencing Project Consortium 2004). These include chemosensation (in particular, olfaction and pheromone detection), reproduction (including placental growth factors and pheromones), toxin degradation (by enzymes such as cytochrome P450s), and immunity and host defense (such as T-cell receptors, immunoglobulins, and alpha-/beta-defensins) (Emes et al. 2003; Castillo-Davis et al. 2004). These functions are critical to the survival and reproduction of adults. By way of contrast, transcription factors or genes that are involved in embryonic development are rarely lineage specific, as these are usually retained without duplication or loss, and without extensive sequence divergence, in each of these mammalian lineages (Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002; Rat Genome Sequencing Project Consortium 2004; Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005).

We sought to identify lineage-specific gene duplicates or “inparalogs” (Sonnhammer and Koonin 2002) without recourse to an out-group species by reconstructing the phylogenetic relationships for all Homo and of Monodelphis genes. Our PhyOP pipeline (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006) infers orthology and paralogy relationships among all predicted transcripts of all Monodelphis and Homo genes using synonymous substitution rates (dS) as a distance metric. Within coding sequence, synonymous sites are the least subject to selection and are a better proxy for evolutionary distances than the protein similarity scores used in many other approaches to orthology prediction. This is especially important for lineage-specific paralogs, many of which have been subject to repeated bouts of adaptive evolution, leading to divergent sequence. PhyOP does not rely on conserved synteny, so that the degree of chromosomal rearrangement across different lineages or in different parts of the genome does not influence orthology prediction. Instead, disruptions in gene order conservation can be used as one of the metrics to identify retrotransposed pseudogenes that are, in general, randomly integrated into the genome. The degree of past selection among lineage-specific genes can then be deduced from estimates of their dN/dS values, defined as the number of nonsynonymous substitutions per nonsynonymous site (dN) relative to the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS). The codeml program from the PAML package (Yang 1997) reliably estimates dS values up to ∼2.5 (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006), and thus, is well suited for investigating mammalian orthologs or mammal-specific paralogs.

Monodelphis autosomes are huge. The smallest, chromosome 6 (MDO6), is roughly the same size as the largest previously sequenced eutherian chromosome, human chromosome 1 (HSA1). The Monodelphis chromosome 1 is three times larger. By way of contrast, the Monodelphis chromosome X (MDOX), at 60.7 Mb, is less than half the size of any eutherian X chromosome that has yet been sequenced. During recombination, there is an obligatory minimum of one chiasma per chromosomal arm (Pardo-Manuel de Villena and Sapienza 2001). Therefore, all else being equal, recombination rates are expected to be greater in chromosomal arms that are shorter (especially Monodelphis X chromosomal arms) than in those that are longer (the large Monodelphis autosomal arms). Higher recombination rates are proposed to drive increases in G+C content due to biased gene conversion (BGC) (Duret et al. 2006). Regions of higher G+C content in eutheria and in chicken also often exhibit higher nucleotide substitution rates (dS) (Buchmann et al. 1983; Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002; Hillier et al. 2004; Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium 2005), consistent with one theoretical model of BGC (Piganeau et al. 2002). dS rates and G+C content among Monodelphis–Homo ortholog pairs can thus further illuminate the complex inter-relationships between recombination, substitution rates, and nucleotide composition.

Our results highlight Monodelphis inparalogs that are likely to contribute to the distinctive biology of metatherians. We also take advantage of our large predicted set of 12,817 one-to-one orthologs between Monodelphis and Homo to compare silent substitution (dS) rates for the large autosomes of Monodelphis with those for its much smaller X chromosome. G+C content and dS are found to be elevated not only in the X chromosome, but also in the 10-Mb subtelomeric regions of all chromosomes. Finally, using Trichosurus vulpecula sequences, we show that the disparity of silent substitution rates between the subtelomeric regions and chromosome interiors has been most acute in the metatherian lineage. We propose a model linking nucleotide content, substitution, and recombination rates with the propensity to evolve large chromosomes.

Results

An improved set of Monodelphis gene predictions

We augmented a set of 19,888 Monodelphis genes from Ensembl with 657 additional gene predictions in the MonDom3 genome assembly (see Methods). These additional predictions were enriched in Monodelphis inparalogs. Our assignments of orthology and paralogy revealed a further 130 genes representing adjacent paralogs that had been merged erroneously. We were also able to identify and discard 1402 putative pseudogenes. These included retrotransposed copies of multi-exon genes; genes with multiple disruptions to their coding sequence; those showing sequence similarity to retroviral and transposable elements such as LINE1; and also some noncoding sequence erroneously predicted from the reverse strand of presumably functional protein coding sequence. This resulted in a final protein coding gene count of 18,639. By comparison, our similarly estimated minimum gene count in Homo sapiens is 20,806, which is comparable to what we previously obtained comparing the dog and human gene sets (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006).

Homo–Monodelphis orthologs

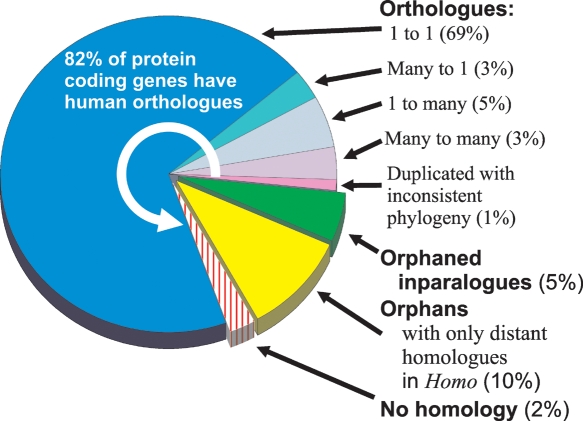

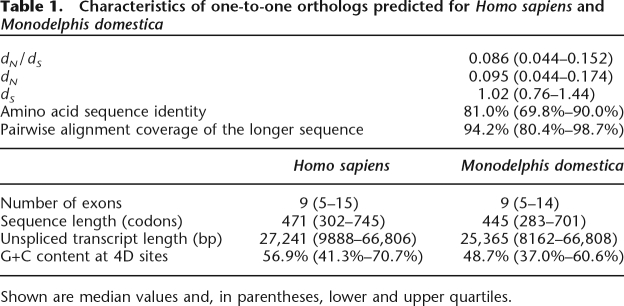

Orthology between Monodelphis and Homo genes, together with Monodelphis- or Homo-lineage-specific paralogy, were assigned using PhyOP (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006). A total of 82% (15,250) of Monodelphis genes were predicted to have Homo orthologs; 12,817 of these were orthologous to only a single Homo gene (“one-to-one orthologs”) (Fig. 1). The full set of genes together with orthology and paralogy relationships are available from http://wwwfgu.anat.ox.ac.uk/download/monodelphis. The median dS value for one-to-one orthologs was 1.02 (Table 1). As expected from the earlier divergence of birds, and the later branching of other eutherian mammals from the human lineage, this value is intermediate between that for human and chicken (1.66; Hillier et al. 2004), and the median dS for human and dog (0.36; Goodstadt and Ponting 2006) or human and mouse (0.60; Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002).

Figure 1.

Proportion of Monodelphis domestica genes with Homo orthologs. The majority (82%) of protein coding genes have PhyOP-predicted orthologs among human genes. The classes of orthology relationships are indicated by counts of Homo orthologs followed by Monodelphis. Thus, a one-to-many relationship refers to a single Homo gene that is orthologous to several Monodelphis-specific duplications. Many of the genes with no predicted orthology with a Homo gene are nevertheless closely related to one or more Monodelphis genes with a low dS, indicating that these are Monodelphis-specific duplications. These are labeled as “Orphaned inparalogues.” This class includes genuine biological losses in the eutherian or human lineage, as well as heuristic failures in the PhyOP-prediction pipeline. The latter are often related to errors in gene predictions in difficult cases where there are many adjacent tandem duplications, such as among KRAB-ZnF genes. Similarly, many of the Monodelphis genes which have no plausible candidate ortholog in the human genome (labeled “Orphans with only distant homologues in Homo”) are likely to involve problematic gene predictions. The Monodelphis genes in the “No homology” class do not have significant BLAST alignments (E < 10−5) covering the majority of the sequence (75% of the shorter of the pair of sequences, and involving more than 50 residues). Most of these appear to be fragmentary, chimeric, or erroneous gene predictions, or noncoding sequence.

Table 1.

Characteristics of one-to-one orthologs predicted for Homo sapiens and Monodelphis domestica

Shown are median values and, in parentheses, lower and upper quartiles.

The median value of dN/dS for Homo and Monodelphis one-to-one orthologs was 0.086. This is lower than the median dN/dS estimated for the primate lineage (0.112), but comparable to the median dN/dS rate for the mouse lineage (0.088; Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002). As deleterious mutations are more effectively purged among species with larger effective population sizes (Ohta 1973), we can infer from these dN/dS rates that the effective population sizes in the marsupial lineage, since the last common ancestor with eutherians, have been similar to those within the murid rodent lineage, and have been larger than those within the human lineage since the primate-rodent last common ancestor.

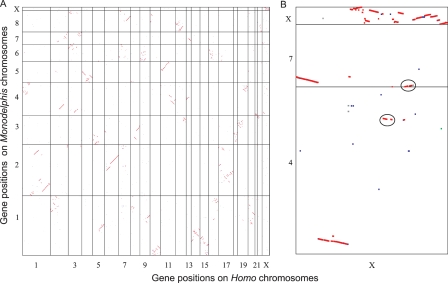

Conserved synteny

Within the nine Monodelphis chromosomes there are 415 “macro-synteny” blocks (see Methods), within which fine-scale gene order and transcriptional orientation have been largely preserved in human chromosomes. There are, however, a number of large-scale rearrangements, such as inversions and translocations (Fig. 2). This number of synteny blocks is similar to that found by whole-genome alignment methods (Mikkelsen et al. 2007). We find that half of all Monodelphis one-to-one orthologs reside in macro-synteny blocks containing 82, or fewer, Homo one-to-one orthologs, which is considerably smaller than the equivalent numbers, 151 and 167, in the dog and mouse, respectively (L. Goodstadt, unpubl.). Since eutherian karyotypes have been relatively stable along the human lineage (Wienberg 2004), it thus appears likely that considerable chromosomal rearrangements have occurred either in the lineage from the therian last common ancestor to the earliest eutherian and/or in the metatherian lineage to Monodelphis.

Figure 2.

Oxford Grid (Edwards 1991) of PhyOP orthologs showing Homo–Monodelphis synteny blocks. (A) Genomic Synteny for all Monodelphis and Homo chromosomes. Genes are plotted in consecutive gene order along the Monodelphis chromosomes MDO1-8 and MDOX, and along the Homo chromosomes HSA1-22 and HSAX. One-to-one, one-to-many, many-to-one, and many-to-many Homo-to-Monodelphis orthologs are displayed as red, green, blue, and black dots, respectively. Diagonal lines represent genomic segments with conserved synteny. (B) The syntenic relationships for the ancient region of the Homo X chromosome that is syntenic to the Monodelphis X chromosome, and the more recently derived regions on the short arm of HSAX that are syntenic to MDO4 and MOD7. The circled regions have been placed on MDO4 and MDO7 in the current Monodelphis assembly 3, but FISH analyses map these regions to the Xq arm of MDOX (M. Breen and P. Water, pers. comm.).

Substitution rates and G+C content are elevated in the metatherian X chromosome

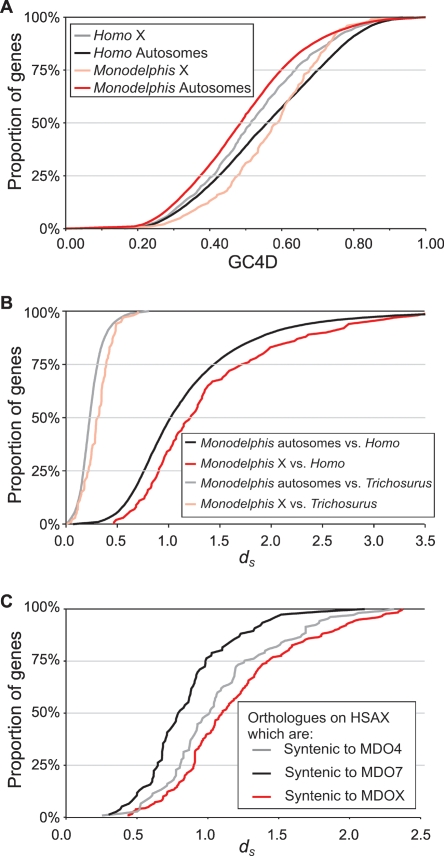

We investigated G+C content since this strongly covaries with dS among eutheria (Matassi et al. 1999; Lander et al. 2001; Hardison et al. 2003; Webber and Ponting 2005). Specifically, we considered GC4D, the G or C content of the third position of fourfold degenerate codons in genes, which correlates strongly with the G+C content of their surrounding regions (Eyre-Walker and Hurst 2001; Duret et al. 2002). We observed that the dS values of Monodelphis and Homo one-to-one orthologs correlate well with their GC4D values (Spearman’s ρ = 0.51 and 0.59, respectively). Similarly, Monodelphis and Homo orthologs’ GC4D contents were also highly correlated (Spearman’s ρ = 0.73). These rank correlations are intermediate between those for pairs of eutherians, and those for eutherians and chicken (Webber and Ponting 2005), confirming that a large part of mammalian G+C composition is ancestral.

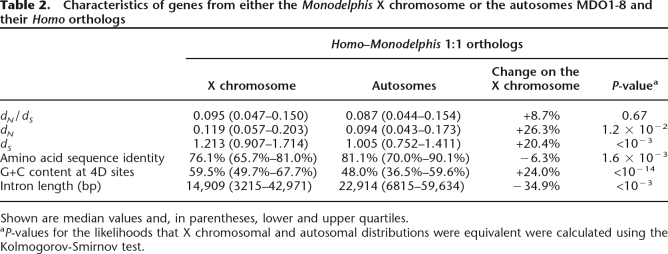

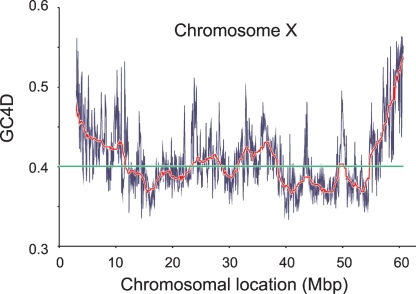

We found, however, that the GC4D and dS values of orthologs are not distributed uniformly among the nine Monodelphis haploid chromosomes. GC4D and dS values are significantly elevated (P < 10−14 and P < 10−3, respectively) for the Monodelphis X chromosome relative to the autosomes (Fig. 3A,B; Table 2). These increases in GC4D and dS values appear to be characteristic of metatherian rather than eutherian X chromosomes. No elevations in dS were apparent for the portions of the human X chromosome that are syntenic to the Monodelphis chromosomes 4 and 7 and that appear to have conjoined the rest of the X chromosome early in eutherian evolution (Glas et al. 1999) (Figs. 2B, 3C; Supplemental Table 1). Moreover, nucleotide substitution rates and overall G+C contents are known to be suppressed, not elevated, in eutherian X chromosomes relative to their autosomes (Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002).

Figure 3.

G+C Content at 4D sites (GC4D) and dS in the Monodelphis and Homo X chromosomes. (A) GC4D values of Monodelphis genes in 1:1 orthology relationships with Homo genes. The cumulative distribution of GC4D for orthologs on the Monodelphis X chromosome is shifted to higher values compared with that for orthologs on Monodelphis autosomes, and genes on the Monodelphis X chromosome have a much increased median GC4D. This is exactly the opposite of the situation among Homo orthologs, where X chromosome genes have reduced GC4D. (B) The increased GC4D on the Monodelphis X chromosome is accompanied by an increase in median dS and a rightward shift of the dS cumulative distribution. This effect is even more pronounced when comparing orthologs between Monodelphis and Trichosurus, suggesting that much of the increase in dS has taken place along the marsupial lineage. (C) The dS for Homo–Monodelphis orthologs that lie on the Homo X chromosome and that are syntenic to the Monodelphis chromosome X or to chromosomes 4 and 7. Among orthologs on the Homo X chromosome, only those that are also found on the Monodelphis X chromosome have elevated dS, confirming that this is largely a marsupial-specific phenomenon.

Table 2.

Characteristics of genes from either the Monodelphis X chromosome or the autosomes MDO1-8 and their Homo orthologs

Shown are median values and, in parentheses, lower and upper quartiles.

aP-values for the likelihoods that X chromosomal and autosomal distributions were equivalent were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

To further investigate whether the increase in X chromosome dS is specific to metatheria, we compared Monodelphis genes with candidate orthologs from another marsupial, the Australian silver-gray brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula). We aligned 111,634 Trichosurus expressed sequence tags (ESTs) to Monodelphis predicted genes and derived orthology relationships using a heuristic based on least divergence (smallest dS value; see Methods). The median dS value between the marsupial orthologs that are autosomal in Monodelphis is 0.28 (n = 7804), whereas that for orthologs, which are X chromosomal in Monodelphis, is 0.33 (n = 93) (Fig. 3C). (X chromosomal content is largely conserved between these two species [Rens et al. 2001].) These differences are highly significant (P < 10−5). These results would be consistent with X chromosome elevation of dS being largely a characteristic of the metatherian, rather than the eutherian, lineage.

Substitution rate and G+C content elevations in subtelomeric regions

We had previously noted a similar elevation of GC4D and dS values for the smaller microchromosomes of chicken, relative to their larger macrochromosomes (Hillier et al. 2004). Increased GC4D and dS values for chicken microchromosomes appear to be related to a more general phenomenon: Sequence from chromosome interiors located away from telomeres is associated with reduced G+C and lowered dS. It seemed possible that the smaller proportion of interstitial sequence in the interior of the Monodelphis X chromosome could best explain the increased GC4D and dS values. If so, we expect decreased GC4D and dS in the autosomes simply because of their greater fractions of interstitial sequence.

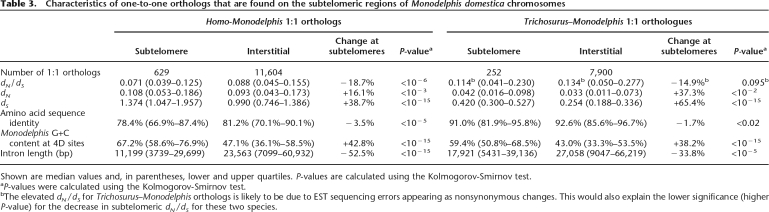

Indeed, we find that in the Monodelphis, the median GC4D and dS values of genes within 10 Mb of all assembled chromosomal telomere ends (0.67 and 1.37, respectively) are 43% and 38% higher than they are within interstitial regions (0.47 and 0.99, respectively) (Fig. 4; Table 3; Supplemental Fig. 1). These differences are highly significant (P < 10−14 and P < 10−3). We then investigated whether similar elevations were apparent for Trichosurus genes whose Monodelphis orthologs are within 10 Mb from a chromosomal end. The median dS value (0.42; n = 252) of such Trichosurus genes is higher still than both the median dS value (0.33; n = 93) between X chromosomal genes for these species and the median dS value (0.25; n = 7900) for autosomal genes. The 65% increase in subtelomeric silent substitutions in Monodelphis–Trichosurus comparisons was substantially higher than that in Monodelphis–Homo orthologs (39%), indicating that elevation of dS in subtelomeric regions is a characteristic of the metatherian, rather than the eutherian, lineage.

Figure 4.

G+C content along the Monodelphis X chromosome. This plot shows the increase in G+C content at the telomeric end of the long arm of the Monodelphis X chromosome. The thin blue lines show the G+C content for adjacent 50-kbp windows along MDOX, while the thick red line is a running average of 50 such windows. The average G+C content for the entire chromosome is shown by the horizontal green line.

Table 3.

Characteristics of one-to-one orthologs that are found on the subtelomeric regions of Monodelphis domestica chromosomes

Shown are median values and, in parentheses, lower and upper quartiles. P-values are calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

aP-values were calculated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test.

bThe elevated dN/dS for Trichosurus–Monodelphis orthologs is likely to be due to EST sequencing errors appearing as nonsynonymous changes. This would also explain the lower significance (higher P-value) for the decrease in subtelomeric dN/dS for these two species.

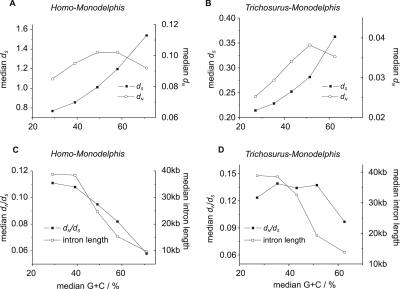

Increased efficacy of selection within high G+C regions

We had reason to believe that the same positional biases would be found for evolutionary rates (dN/dS), and that all of these observations arise from correlations with high-recombination rates (see Discussion). For the set of 12,898 1:1 Monodelphis–Homo orthologs and for the set of 6713 Monodelphis–Trichosurus ortholog alignments that had at least 100 aligning codons, we observed significant negative rank correlations between G+C and dN/dS (P < 1 × 10−6) (Fig. 5).

Figure 5.

dN, dS, dN/dS, and intron length vary with G+C content at 4D sites among Monodelphis–Homo and Monodelphis–Trichosurus 1:1 orthologs. (A,C) The variation of the median values for dN, dS, dN/dS, and Monodelphis intron lengths in Monodelphis–Homo 1:1 orthologs. (B,D) The same relationships for 1:1 orthologs between the two marsupials Monodelphis and Trichosurus. The orthologs were divided into five equally populated classes according to Monodelphis G+C content at 4D sites (GC4D). We found that median dN/dS dropped from 0.12 for Trichosurus orthologs and 0.11 for Homo orthologs in the lowest G+C class (G+C <31.5% and <34.5%, respectively) to a median dN/dS of 0.10 and 0.058 in the highest G+C class (G+C >56.1% and >63.5%, respectively). The higher median dN/dS values for orthologs from the two marsupial species is likely to stem, in part, from Trichosurus EST sequencing errors that disproportionately affect dN over dS. Genes with high GC4D also exhibit higher median dS and dN values and have reduced intron lengths.

We then considered whether Monodelphis genes contained within high G+C regions have unusually short introns, as might be expected from previous observations linking high recombination rate and decreased intron length (Duret et al. 1995; Montoya-Burgos et al. 2003). Indeed, median intron lengths fell by fourfold for increasing G+C (P < 1 × 10−6) (Fig. 5). Significant reductions in both dN/dS and intron lengths are also seen for Monodelphis–Homo orthologs from the subtelomeres of Monodelphis chromosomes and from chromosome X (Tables 2, 3).

Lineage-specific biology and Monodelphis paralogs

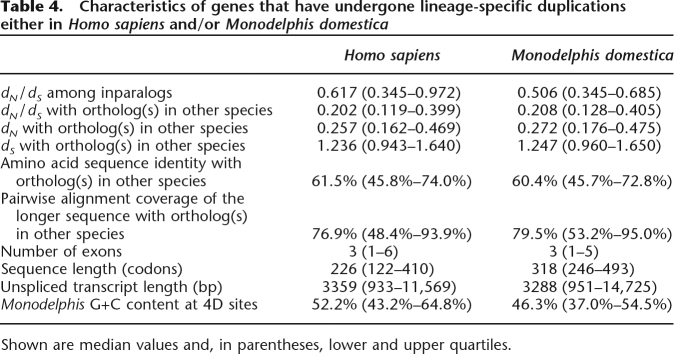

Using PhyOP, we identified 2733 Monodelphis and 4105 Homo genes that have each arisen from duplications in their respective lineages since their last common ancestor. In the primary publication presenting the Monodelphis genome (Mikkelsen et al. 2007), we describe how these inparalogs are likely to participate in immunity or host defense, chemosensation, toxin degradation, and reproduction (see Supplemental Tables 2–6). The median dN/dS value for all Monodelphis inparalogs (0.51) (Table 4) is sixfold greater than that for Monodelphis–Homo orthologs (0.086), indicating that evolution of these genes has occurred under greatly relaxed constraints or widespread and recurrent episodes of adaptation.

Table 4.

Characteristics of genes that have undergone lineage-specific duplications either in Homo sapiens and/or Monodelphis domestica

Shown are median values and, in parentheses, lower and upper quartiles.

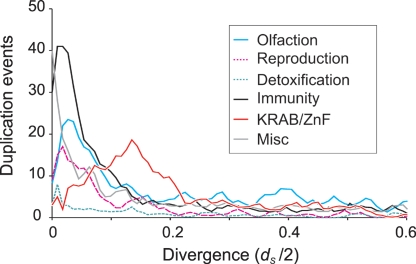

KRAB zinc fingers have a different duplication time profile

As in other mammals, the KRAB zinc finger gene family has expanded rapidly in Monodelphis, with at least 350 members (Supplemental Table 5). Although we now know such genes have an ancient origin prior to the emergence of vertebrates (Birtle and Ponting 2006), the opossum is the most distantly related organism to humans known to have such a greatly expanded repertoire. Most Monodelphis inparalogs have low divergences (dS values), suggesting that they are the result of recent duplications relative to the origin of the metatherian lineage (Fig. 6). KRAB zinc finger genes are the exception to this general rule. Among all functional classes, these genes appear to have experienced a burst of duplication at dS ∼ 0.14. Following the proposal of others (Vogel et al. 2006), the preferential localization of KRAB zinc finger genes in heterochromatic sequence may have led to a recent reduction in the duplication or loss of these genes during recombination.

Figure 6.

Inferred rates of duplication for Monodelphis inparalogs among different functional categories. The timing of duplication events for Monodelphis-specific inparalogs were inferred from the dS-based rooted phylogenetic tree, and thus appears on a scale of dS/2 units. Although dS values vary substantially among genes (Fig. 3B), on average, a dS/2 value of 0.25 represents ∼90 million years. Genes in most functional classes (including olfaction, reproduction, detoxification, and immunity) follow a profile typical of other mammals with duplications peaking very recently. This would be in accordance with a rapid gene birth and death model. It is likely that reduction in the number of most recent duplications (dS/2 < 0.02) is due partly to the collapse of nearly identical sequence in the assembly, and partly to underprediction of sequence-similar adjacent paralogs and overestimation of very small dS values. The duplications of KRAB-ZnF genes are prominent in peaking at dS/2 ∼ 0.14.

Chemosensation

The large expansions in gene families involved in chemosensation in the Monodelphis lineage relative to human provide ample evidence of their importance in nocturnal foraging and pheromonal communication (Supplemental Tables 2, 3). Monodelphis olfactory receptors (ORs), and V1R or V2R vomeronasal receptors have experienced numerous episodes of gene duplications, presumably as adaptive responses to changes in their environments and to conspecific competition. Those clades that experienced two or more gene duplications contain 468, 50, and 110 duplicated lineage-specific OR, V1R, and V2R genes, respectively. The large expansion of vomeronasal receptors may have been concomitant with the acquisition of unique structural adaptations in the Monodelphis vomeronasal organ, including a nuzzling “pad” thought to facilitate uptake of odorants (Poran 1998).

Three clusters of lipocalins have also been expanded, including one whose orthologs encode the major urinary protein pheromone in mice. However, Monodelphis uses skin and glandular secretions rather than urine for scent marking (Zuri et al. 2005). If these genes represent Monodelphis pheromones, they are thus likely to exhibit very different tissue-expression profiles. Another lipocalin cluster is orthologous to developmentally regulated milk protein genes in the tammar wallaby (Trott et al. 2002). Beta-microseminoprotein, an abundant constituent of seminal plasma, has been duplicated extensively in the Monodelphis lineage, resulting in 12 copies, whereas all other mammals (except New World monkeys that have three) have one (Makinen et al. 1999). There is evidence for positive selection at six sites among these Monodelphis inparalogs (data not shown), suggesting a role in conspecific competition during fertilization (Swanson and Vacquier 2002).

Immunity-related genes are evolving the fastest

The fastest evolving Monodelphis lineage-specific genes have roles in immunity and host defense. Their median dN/dS value of 0.80 (Mikkelsen et al. 2007) is exceptionally high and perhaps indicates that the usual mammalian “genetic arms race” (Dawkins and Krebs 1979) with pathogens and parasites has been particularly severe in this marsupial lineage. Many immunoglobulin (IG) domain–containing proteins, such as IG chains, butyrophilins, leukocyte IG-like receptors, T-cell receptor chains, and carcinoembryonic antigen-related cell-adhesion molecules were found to be greatly expanded in the Monodelphis lineage (Supplemental Table 4). The chemokine CCL4 is also greatly expanded in Monodelphis, with a total of five copies. CCL4 inhibits infection by retroviruses such as HIV-1 in humans and may play a similar role in Monodelphis (Menten et al. 2002). Although lineage-specific duplication and adaptation of pancreatic RNases have previously been associated with dietary adaptations in foregut-fermenting herbivorous mammals (Zhang et al. 2002), the modest expansion to three homologs in Monodelphis may serve an immunological rather than a dietary role, since this opportunistic omnivore possesses only a relatively simple alimentary canal (see also Yu and Zhang 2006).

Dietary adaptation

In other ways, the Monodelphis genome does exhibit evidence for past adaptation to dietary changes. The six copies of the single exon hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase homologs on chromosome 4 (∼346 Mb) may reduce the loss of nitrogen via urinary excretion of allantoin, as suggested previously (Noyce et al. 1997), contributing to the marsupial tolerance of nitrogen-poor diets (Hume 1982). Other genes that have been duplicated in the genome are SLC39A4, encoding a zinc transporter whose expression is up-regulated in mouse under conditions of dietary zinc deficiency (Dufner-Beattie et al. 2003) and thiamine pyrophosphokinase 1 homologs, which are likely to be involved in the salvage of thiamine (vitamin B1). The duplication of various genes encoding gastric enzymes in the Monodelphis lineage have been discussed elsewhere (Mikkelsen et al. 2007).

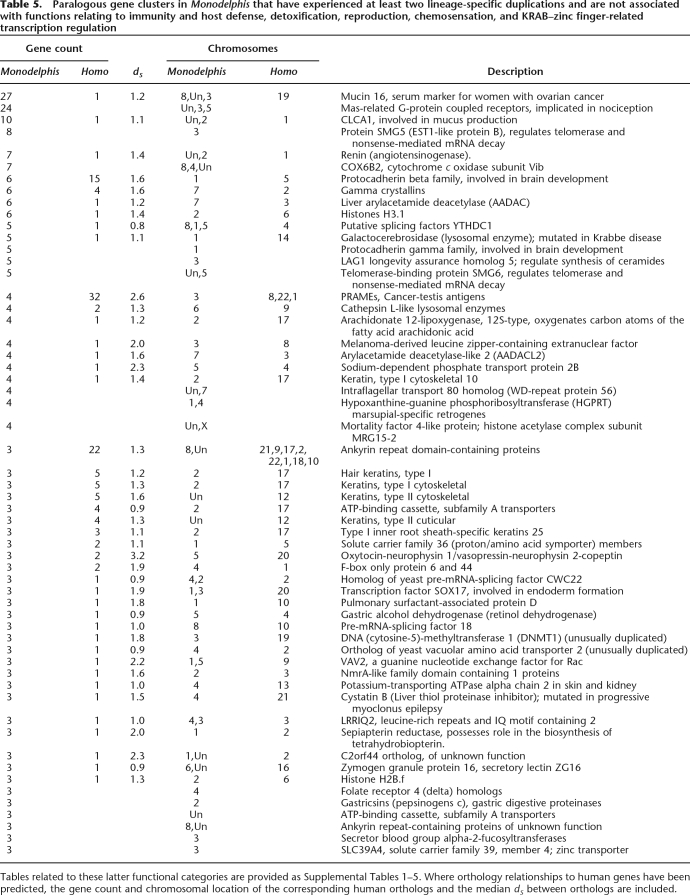

Many other Monodelphis-specific genes have functions that fall outside of the typical mammalian themes of chemosensation, reproduction, immunity, and detoxification (Table 5). Notable among these genes are those encoding proteins involved in mucus production (CLCA1 and MUC16), splicing factors (SMG5, YTHDC1, SMG6, and CWC22 [KIAA1604]), lysosomal enzymes (cathepsin L and GALC), renins, and multiple keratins. The identification of these genes should now allow greater scrutiny of their contributions to Monodelphis- and marsupial-specific biology.

Table 5.

Paralogous gene clusters in Monodelphis that have experienced at least two lineage-specific duplications and are not associated with functions relating to immunity and host defense, detoxification, reproduction, chemosensation, and KRAB–zinc finger-related transcription regulation

Tables related to these latter functional categories are provided as Supplemental Tables 1–5. Where orthology relationships to human genes have been predicted, the gene count and chromosomal location of the corresponding human orthologs and the median dS between orthologs are included.

Finally, we were interested in whether orthologs of Didelphis marsupialis DM43 and DM40, which confer natural resistance to snake venoms in this related marsupial (Neves-Ferreira et al. 2000), could be found in Monodelphis. However, despite exhaustive searches of the current genome assembly, no substantially similar sequences to DM43 and DM40 were identified, perhaps indicating that these genes have evolved particularly rapidly.

Discussion

With the newly sequenced genome of Monodelphis domestica comes tremendous potential for attributing genetic and genomic variation to metatherian- or eutherian-specific traits. We have shown that 82% of Monodelphis genes have demonstrable orthologs in a representative eutherian, Homo sapiens. Fifteen percent of Monodelphis genes appear to have arisen through gene duplications in the metatherian lineage. Many of these exhibit relatively little divergence (Fig. 6), indicating that they have arisen recently and may succumb eventually to inactivation and loss over longer time periods. This would be in agreement with what is seen in other mammals (International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium 2004) and metazoans (Lynch and Conery 2000), and would be consistent with a model of rapid birth and death of duplicate genes. Most Monodelphis inparalogs fall into the same broad functional classes seen in eutherian gene duplications. However, there are at least 283 duplicated genes (Table 5) whose functions do not belong to any of these popular categories. Each metatherian-specific gene is now available for further investigation of its contribution to the unique biology of this lineage (Samollow 2006).

Predicted orthologs from Trichosurus vulpecula

We have also predicted 8237 genes from the Australian marsupial Trichosurus vulpecula (Kerle et al. 1991) as orthologs of Monodelphis genes. These enable comparisons between a South American and an Australian marsupial whose lineages diverged, we estimate, 46–53 Mya, around the date (∼45 Mya) at which land migration via Antarctica ceased between Australia and South America (Li and Powell 2001). These estimates were obtained by dividing these marsupials’ median autosomal or X chromosomal dS values by the equivalent values between Homo and Monodelphis and scaling by the estimated time (170–190 Mya) separating them from their last common ancestor (Kumar and Hedges 1998; Woodburne et al. 2003). This divergence time is considerably more recent than the previously estimated 60–70 Mya (Nilsson et al. 2004).

Protein coding gene counts

Our studies also contribute to an understanding of the differences in protein coding gene numbers encoded within different mammalian genomes. Previous estimates of the human gene count, for example, appear to have been inflated because of contributions from retrotransposed pseudogenes and transcribed, but noncoding, sequences (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006). Our previous lower-bound estimate of the human gene count, from a comparison with the predicted set of dog protein coding genes, was 19,700 (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006), and a comparable estimate (20,806) arises from this comparison with the predicted Monodelphis gene set. These estimates serve to re-emphasize that mammalian gene counts, in general, are little different from those of nonvertebrate metazoa such as nematode worms, and thus should not be considered as an appropriate measure of organismal complexity. The lower estimated gene count in Monodelphis (18,639) is likely to be the result of under-prediction rather than lineage-specific gene gains or losses. The missing genes may be partly attributed to the draft quality of the genome sequence. However, they probably mostly reflect the challenges of using distant-related eutherian evidence to find genes in a marsupial without the benefit of a large set of Monodelphis transcripts.

Decline in mammalian G+C content

It has been suggested that G+C content has declined substantially during metatherian evolution (Belle et al. 2004). This would certainly be consistent with the high G+C content of the platypus (Ornithorhynchus anatinus) (Margulies et al. 2005). Our results show that any such decline would have been most precipitous for the Monodelphis autosomes, particularly in their interstitial regions located well away from their telomeres. Decreases in G+C content are often assumed to be a consequence of the high mutation rate of cytosines in methylated CpG dinucleotides (Brown and Jiricny 1987). We note that Monodelphis possesses two inparalogs of the DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferase 1, whereas eutherians (and most other vertebrates) have only one. If these two copies together possess higher aggregate DNA methylation rates than their single eutherian counterpart, this could explain, at least in part, the stronger decline in G+C among metatheria than in eutheria.

High metatherian recombination rates in the short X chromosome and subtelomeric regions

The decline in G+C appears to have least affected the Monodelphis X chromosome and the subtelomeric regions of autosomes. Several lines of evidence suggest that this may be a consequence of biased gene conversion driven by female-specific recombination. Allelic gene conversion during meiotic recombination is proposed to be biased toward insertion of G or C over A or T, leading to an increase in G+C content within highly recombining regions (Duret et al. 2006).

The Monodelphis X chromosome can be expected to have a higher recombination rate because of its considerably (four- to 12-fold) smaller size and the obligatory minimum of one chiasma per chromosomal arm. This would be despite the lower recombination rate in Monodelphis females (Samollow et al. 2004). (Recombination in the X chromosome is, by definition, female specific.) Although we as yet lack comprehensive data, it appears that chiasmata in female meiotic cells in Monodelphis and other marsupials are concentrated close to telomeres (Bennett et al. 1986), contributing to a bias toward recombination at chromosome ends, and of course, within the X chromosome. This is exactly where the highest G+C values can be seen (Fig. 4). Chiasmata are more evenly distributed in male cells (Hayman et al. 1988).

Increased G+C content and recombination have previously been associated with increased numbers of synonymous substitutions (Wolfe et al. 1989; Matassi et al. 1999; Hardison et al. 2003; Webber and Ponting 2005). We see an increase in dS not only in regions with high G+C content, but also specifically in the X chromosome and subtelomeric regions where we expect increased recombination. The comparisons of Monodelphis–Trichosurus orthologs suggest that these changes have occurred largely on the marsupial lineage.

Recombination promotes greater efficiency of selection

High recombination is believed to increase the efficiency of selection by disrupting interference between neighboring mutations, the “Hill-Robertson” effect (Hill and Robertson 1966). Because most nonsynonymous mutations are deleterious, this would tend to increase purifying selection. A higher recombination rate in the marsupial X chromosome and subtelomeric regions might then explain the reduced dN/dS among Monodelphis orthologs from these regions, as well as among genes with high G+C. The same evolutionary forces may explain the decrease in intron lengths in such Monodelphis regions, a phenomenon that has also previously been associated with high recombination (Duret et al. 1995; Montoya-Burgos et al. 2003).

Chromosomal rearrangements

The decline of G+C content in metatherian autosomes may also be associated with reduced rates of intra- or interchromosomal rearrangements. This is because synteny break regions, at least in eutheria, are enriched within regions exhibiting high G+C levels and dS rates (Marques-Bonet and Navarro 2005; Webber and Ponting 2005). Thus, we might expect rearrangements to have occurred preferentially in the Monodelphis X chromosome and near the autosomal telomeres. Indeed, we note that one type of rearrangement, namely segmental duplication, is over-represented in the X chromosome relative to the remainder of the genome (Mikkelsen et al. 2007).

This theory, building upon our own work (Webber and Ponting 2005) and that of others (Duret et al. 2002, 2006; Marques-Bonet and Navarro 2005), assumes that high recombination rates maintain high G+C levels, and that chromosomal regions of high G+C are unusually susceptible to breakage and consequent rearrangement. It provides five testable predictions. (1) G+C-poor chromosomes tend to be larger, which is the case for human (Duret et al. 2002), chicken (Hillier et al. 2004), and Monodelphis (this study) chromosomes. (2) G+C-poor chromosomes have experienced less recombination. Although more data are needed, there is evidence that this is indeed the case (Samollow et al. 2004). (3) G+C-rich regions preferentially segregate to chromosomal ends as a direct result of their susceptibility to breakage (Webber and Ponting 2005). As discussed above, regions enriched in G+C content, and with high (female-specific) recombination rates, exhibit a strong tendency to be located near telomeres. (4) Conversely, low G+C regions preferentially segregate to within chromosomal interiors and would be relatively refractive to breakage. The very limited number of chromosomal rearrangements observed among diverse marsupials would appear to support this (Rens et al. 2001). (5) Susceptibility to recombination is preserved, in part, across the mammalia; it is an ancestral, rather than a derived trait. This would explain the high rank order correlation between the GC4D values in Monodelphis and Homo (as they are between chicken and eutheria (Webber and Ponting 2005). Although genetic maps are only available for a few mammals, it is known that recombination rates in human, rat, and mouse syntenic sequence are moderately correlated (Jensen-Seaman et al. 2004). These five predictions will be available for testing upon the sequencing of additional genomes, such as those of the platypus, cattle, and songbird.

These issues of variable rates of recombination, mutation, and selection, together with the identification of genes that distinguish, say, Australian from American marsupials, will necessitate the sequencing of a second marsupial’s genome. The Monodelphis genome sequence has provided a broad perspective of the features that distinguish metatherian from eutherian genomes. However, until a second genome of this distinctive order of mammals is sequenced, its idiosyncrasies will, by necessity, not be separable from general metatherian characteristics.

Methods

A more comprehensive set of Monodelphis gene predictions

We augmented a preliminary set of Monodelphis gene predictions from Ensembl with additional gene predictions using the Exonerate program (version 0.9) (Slater and Birney 2005) on the same MonDom3 genome assembly. Briefly, we used Homo protein coding transcripts (Ensembl release version 36 based on NCBI assembly 35) as templates for predicting Monodelphis transcripts. Exonerate predicted transcripts that overlapped an existing Ensembl prediction were discarded.

Lineage-specific paralogs present greater difficulties for gene prediction than other genes, due to their more rapid sequence divergence (Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium 2002), and their frequent location in tandem clusters. We, therefore, initiated a second round of gene prediction using both Homo and Monodelphis sequences from gene families with Monodelphis lineage-specific duplications (see below) as templates.

Altogether, we were able to predict 657 additional Monodelphis genes to supplement Ensembl data. A more detailed description of the gene prediction pipeline is contained in the Supplemental information.

Inferring orthology and paralogy relationships

Orthology and paralogy relationships between Monodelphis and Homo genes were predicted using PhyOP (Goodstadt and Ponting 2006). This reconstructed the phylogeny for all Monodelphis and Homo transcripts using dS as a proxy for their evolutionary distances. We collated all peptide sequences from Monodelphis (assembly 3) and Homo (Ensembl release 38 based on NCBI assembly 36) and identified homologs using BLASTP and an E-value upper threshold of 1 × 10−5. We only discarded spurious and fragmentary alignments that were shorter than 50 residues or where <75% of the shorter sequence was included in the alignment. Homologs were clustered together and the number of synonymous substitutions per synonymous site (dS) was calculated using the codeml program from the PAML package (Yang 1997) with default settings for pairwise analyses (F3X4). We took sets of sequences related by dS values previously shown in simulation to have acceptable reliability (dS < 2.5) and constructed rooted phylogenies using a modified version of the kitsch algorithm (applying the Fitch-Margoliash criterion) from the PHYLIP (Felsenstein 1981) suite of programs. Orthology relationships among the transcripts were inferred automatically by minimizing the number of duplications that must be invoked to reconcile the transcript phylogeny with the species tree.

The human gene set included a number of allelic variants on chromosomes 5, 6, and 22. We discarded such sequence unless the corresponding allele was missing from the same loci in the reference genome or unless the two alleles showed substantial divergence (dS > 0.5).

We observed 33,446 Homo transcripts from 16,471 genes and 26,360 Monodelphis transcripts from 16,261 genes in orthology relationships. A single representative transcript for each gene was then chosen in order to map transcript phylogeny to orthology relationships between genes. We iteratively selected transcript pairs from both species with the lowest dS value, while eliminating overlapping alternative transcripts. This procedure also allowed the identification of erroneously merged adjacent paralogs whose representative transcripts after separation did not overlap. The heuristic for the selection of representative transcripts necessarily left 347 Homo and 268 Monodelphis orthologous genes whose transcripts were inconsistent with the final representative phylogenies (referred to as “orthologs with inconsistent phylogeny”).

Lineage-specific paralogs

We also sought to identify those “orphaned” genes that have been duplicated in the Homo or Monodelphis lineages (inparalogs), but whose ortholog in the other species is either not present or has not been predicted correctly. We selected clusters of transcripts without predicted orthology whose divergences and phylogeny indicate species-specific duplications, together with transcripts from orthologs with inconsistent phylogeny. We filtered out all pairwise relationships that are likely to predate the divergence between the Monodelphis and Homo lineages by using a dS cut-off equivalent to the median dS value (1.02) between predicted one-to-one orthologs. As in the case of the prediction of orthologs, sets of inparalogs were created by selecting transcript pairs from both species with the lowest dS value, while eliminating overlapping alternative transcripts. This procedure similarly allowed the identification of erroneously merged adjacent paralogs.

As described above, we took Homo and Monodelphis sequences from duplicated gene families as templates for additional gene prediction. All analyses in this study used orthologs and paralogs inferred from this final gene set.

Identifying pseudogenes

Putative pseudogenes, mostly representing retro-transpositions, were identified by the presence of disruptions (defined by short introns [<10 bp] among Ensembl genes) and the loss of introns along with the absence of synteny (see below). We labeled as pseudogenes any nonsyntenic (“dispersed”) gene with one or more disruptions, syntenic genes with multiple disruptions, and dispersed single exonic genes. Any ortholog families with Interpro matches for L1 transposable elements (IPR004244) were also identified as pseudogenes.

Pseudogenes are retrotransposed in random locations and tend, therefore, to be found on multiple chromosomes. For widely dispersed families of orthologs (with members on four or more chromosomes), we first attempted to reliably identify their original “parent” genes (genes from which retrocopies were derived). We selected orthologs that had three or more exons with matching exon boundaries across both species. In such cases, we could then go on to identify retro-transposed pseudogene family members containing two or fewer exons with nonmatching boundaries.

Manual curation of families with three or more inparalogs in the Monodelphis lineage identified another 432 candidate pseudogenes, including retrotransposed genes, retroviral sequences, and genes predicted on the wrong strand. We also labeled as noncoding all Homo genes that do not have an identifiable homolog among Mus musculus (Ensembl version 40.36a), Canis familiaris (Ensembl version 40.1i), or Monodelphis sequences. Many of these are likely to reflect spurious open reading frames called within the untranslated regions of real transcripts (E. Birney, pers. comm.)

Conserved synteny

The orthology relationships allowed us to identify areas of conserved synteny in the Monodelphis and Homo genomes. We constructed “micro-syntenic” blocks by grouping together successive genes with conserved gene order and orientation among predicted 1:1 orthologs in the other species. “Macro-syntenic” blocks could then be identified by concatenating contiguous micro-syntenic blocks that, after rearrangements and inversions, would have conserved gene order in the other species. Loss of synteny, especially in the identification of retrotransposed pseudogenes, was defined as a disruption of the gene order between both upstream and downstream neighbors of its orthologs in the other species by >50 genes.

Trichosurus orthologs of Monodelphis genes

We calculated dS values between Monodelphis predicted transcripts and 111,634 ESTs from an Australian marsupial, the silver-gray brushtail possum (Trichosurus vulpecula). Alignments to the longest predicted Monodelphis transcript of each gene used tfasty and default values (Pearson 2000). Frame-shift positions in alignments were checked for indication of intron run-off and unusually low-sequence identity (<25%); such stretches of alignments were subsequently masked. dS values were calculated using codeml (Yang 1997) and matches with a dS value exceeding three times the lowest dS match for that query were removed. Likely, paralog matches were eliminated by removing all alignments exceeding three times the overall median dS value of 0.26. Each matching EST was then assigned to a particular query sequence by virtue of its lowest dS value. All hits for a query were combined into a consensus sequence with conflicting positions masked. Subsequently, dS values were estimated anew between this consensus sequence and the Monodelphis query sequence. We recovered alignments to ESTs for 8237 predicted Monodelphis transcripts. These exhibited an average 58% of nucleotides covered per transcript. A total of 343 predicted transcripts with EST alignments were located on unplaced contigs in the Monodelphis assembly. On average, 33% of transcript nucleotides were aligned to multiple ESTs.

Genes in subtelomeric regions

Subtelomeric regions were defined as the 10 Mb of sequence at the end of each assembled chromosome sequence. For the Monodelphis metacentric chromosomes (MDO1 and MDO2) (Svartman and Vianna-Morgante 1999), the tail ends of both arms were included. For the other acrocentric/subtelocentric chromosomes (MDO3-8, MDOX), only the tail ends of the long arms were used. Only genes that fell entirely within these defined regions were included in the analyses.

Statistical tests

We used the nonparametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test implemented in the R package (R Development Core Team 2006) to evaluate the statistical significance in comparing distinct distributions.

Acknowledgments

These studies were funded by the UK Medical Research Council. We thank all members of the Monodelphis domestica genome sequencing consortium, in particular, Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, Tarjei Mikkelsen, and Paul Samollow, for their assistance and helpful comments.

Footnotes

[Supplemental material is available online at www.genome.org.]

Article published online before print. Article and publication date are at http://www.genome.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gr.6093907

References

- Belle E.M., Duret L., Galtier N., Eyre-Walker A., Duret L., Galtier N., Eyre-Walker A., Galtier N., Eyre-Walker A., Eyre-Walker A. The decline of isochores in mammals: An assessment of the GC content variation along the mammalian phylogeny. J. Mol. Evol. 2004;58:653–660. doi: 10.1007/s00239-004-2587-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett J.H., Hayman D.L., Hope R.M., Hayman D.L., Hope R.M., Hope R.M. Novel sex differences in linkage values and meiotic chromosome behaviour in a marsupial. Nature. 1986;323:59–60. doi: 10.1038/323059a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birtle Z., Ponting C.P., Ponting C.P. Meisetz and the birth of the KRAB motif. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2841–2845. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btl498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown T.C., Jiricny J., Jiricny J. A specific mismatch repair event protects mammalian cells from loss of 5-methylcytosine. Cell. 1987;50:945–950. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90521-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann P., Schneider K., Gebbers J.O., Schneider K., Gebbers J.O., Gebbers J.O. Fibrosis of experimental colonic anastomosis in dogs after EEA stapling or suturing. Dis. Colon Rectum. 1983;26:217–220. doi: 10.1007/BF02562480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Davis C.I., Kondrashov F.A., Hartl D.L., Kulathinal R.J., Kondrashov F.A., Hartl D.L., Kulathinal R.J., Hartl D.L., Kulathinal R.J., Kulathinal R.J. The functional genomic distribution of protein divergence in two animal phyla: Coevolution, genomic conflict, and constraint. Genome Res. 2004;14:802–811. doi: 10.1101/gr.2195604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium. Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins R., Krebs J.R., Krebs J.R. Arms races between and within species. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 1979;205:489–511. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1979.0081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufner-Beattie J., Wang F., Kuo Y.M., Gitschier J., Eide D., Andrews G.K., Wang F., Kuo Y.M., Gitschier J., Eide D., Andrews G.K., Kuo Y.M., Gitschier J., Eide D., Andrews G.K., Gitschier J., Eide D., Andrews G.K., Eide D., Andrews G.K., Andrews G.K. The acrodermatitis enteropathica gene ZIP4 encodes a tissue-specific, zinc-regulated zinc transporter in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33474–33481. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305000200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Mouchiroud D., Gautier C., Mouchiroud D., Gautier C., Gautier C. Statistical analysis of vertebrate sequences reveals that long genes are scarce in GC-rich isochores. J. Mol. Evol. 1995;40:308–317. doi: 10.1007/BF00163235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Semon M., Piganeau G., Mouchiroud D., Galtier N., Semon M., Piganeau G., Mouchiroud D., Galtier N., Piganeau G., Mouchiroud D., Galtier N., Mouchiroud D., Galtier N., Galtier N. Vanishing GC-rich isochores in mammalian genomes. Genetics. 2002;162:1837–1847. doi: 10.1093/genetics/162.4.1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duret L., Eyre-Walker A., Galtier N., Eyre-Walker A., Galtier N., Galtier N. A new perspective on isochore evolution. Gene. 2006;385:71–74. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2006.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards J.H. The Oxford Grid. Ann. Hum. Genet. 1991;55:17–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1991.tb00394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emes R.D., Goodstadt L., Winter E.E., Ponting C.P., Goodstadt L., Winter E.E., Ponting C.P., Winter E.E., Ponting C.P., Ponting C.P. Comparison of the genomes of human and mouse lays the foundation of genome zoology. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2003;12:701–709. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyre-Walker A., Hurst L.D., Hurst L.D. The evolution of isochores. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2001;2:549–555. doi: 10.1038/35080577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadem B.H., Rayve R.S., Rayve R.S. Characteristics of the oestrous cycle and influence of social factors in grey short-tailed opossums (Monodelphis domestica) J. Reprod. Fertil. 1985;73:337–342. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0730337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Evolutionary trees from DNA sequences: A maximum likelihood approach. J. Mol. Evol. 1981;17:368–376. doi: 10.1007/BF01734359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glas R., Marshall Graves J.A., Toder R., Ferguson-Smith M., O’Brien P.C., Marshall Graves J.A., Toder R., Ferguson-Smith M., O’Brien P.C., Toder R., Ferguson-Smith M., O’Brien P.C., Ferguson-Smith M., O’Brien P.C., O’Brien P.C. Cross-species chromosome painting between human and marsupial directly demonstrates the ancient region of the mammalian X. Mamm. Genome. 1999;10:1115–1116. doi: 10.1007/s003359901174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodstadt L., Ponting C.P., Ponting C.P. Phylogenetic reconstruction of orthology, paralogy, and conserved synteny for dog and human. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2006;2:e133. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.0020133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardison R.C., Roskin K.M., Yang S., Diekhans M., Kent W.J., Weber R., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Roskin K.M., Yang S., Diekhans M., Kent W.J., Weber R., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Yang S., Diekhans M., Kent W.J., Weber R., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Diekhans M., Kent W.J., Weber R., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Kent W.J., Weber R., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Weber R., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Elnitski L., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Li J., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., O’Connor M., Kolbe D., Kolbe D., et al. Covariation in frequencies of substitution, deletion, transposition, and recombination during eutherian evolution. Genome Res. 2003;13:13–26. doi: 10.1101/gr.844103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman D., Moore H., Evans E., Moore H., Evans E., Evans E. Further evidence of novel sex differences in chiasma distribution in marsupials. Heredity. 1988;61:455–458. [Google Scholar]

- Hill W.G., Robertson A., Robertson A. The effect of linkage on limits to artificial selection. Genet. Res. 1966;8:269–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillier L.W., Miller W., Birney E., Warren W., Hardison R.C., Ponting C.P., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Miller W., Birney E., Warren W., Hardison R.C., Ponting C.P., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Birney E., Warren W., Hardison R.C., Ponting C.P., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Warren W., Hardison R.C., Ponting C.P., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Hardison R.C., Ponting C.P., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Ponting C.P., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Bork P., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Burt D.W., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Groenen M.A., Delany M.E., Delany M.E., et al. Sequence and comparative analysis of the chicken genome provide unique perspectives on vertebrate evolution. Nature. 2004;432:695–716. doi: 10.1038/nature03154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes A.L. The evolution of functionally novel proteins after gene duplication. Proc. Biol. Sci. 1994;256:119–124. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1994.0058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hume I.D. Digestive physiology and nutrition of marsupials. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, UK: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium. Finishing the euchromatic sequence of the human genome. Nature. 2004;431:931–945. doi: 10.1038/nature03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen-Seaman M.I., Furey T.S., Payseur B.A., Lu Y., Roskin K.M., Chen C.F., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Furey T.S., Payseur B.A., Lu Y., Roskin K.M., Chen C.F., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Payseur B.A., Lu Y., Roskin K.M., Chen C.F., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Lu Y., Roskin K.M., Chen C.F., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Roskin K.M., Chen C.F., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Chen C.F., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Thomas M.A., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Haussler D., Jacob H.J., Jacob H.J. Comparative recombination rates in the rat, mouse, and human genomes. Genome Res. 2004;14:528–538. doi: 10.1101/gr.1970304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerle J.A., McKay G.M., Sharman G.B., McKay G.M., Sharman G.B., Sharman G.B. A systematic analysis of the brushtail possum, Trichosurus-vulpecula (Kerr, 1792) (Marsupialia, Phalangeridae) Aust. J. Zool. 1991;39:313–331. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S., Hedges S.B., Hedges S.B. A molecular timescale for vertebrate evolution. Nature. 1998;392:917–920. doi: 10.1038/31927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lander E.S., Linton L.M., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Linton L.M., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Birren B., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Nusbaum C., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Zody M.C., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Baldwin J., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Devon K., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Dewar K., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., Doyle M., FitzHugh W., FitzHugh W., et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921. doi: 10.1038/35057062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z.X., Powell C.M., Powell C.M. An outline of the palaeogeographic evolution of the Australasian region since the beginning of the Neoproterozoic. Earth-Science Reviews. 2001;53:237–277. [Google Scholar]

- Lindblad-Toh K., Wade C.M., Mikkelsen T.S., Karlsson E.K., Jaffe D.B., Kamal M., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Wade C.M., Mikkelsen T.S., Karlsson E.K., Jaffe D.B., Kamal M., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Mikkelsen T.S., Karlsson E.K., Jaffe D.B., Kamal M., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Karlsson E.K., Jaffe D.B., Kamal M., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Jaffe D.B., Kamal M., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Kamal M., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Clamp M., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Chang J.L., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Kulbokas E.J., III, Zody M.C., Zody M.C., et al. Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog. Nature. 2005;438:803–819. doi: 10.1038/nature04338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Conery J.S., Conery J.S. The evolutionary fate and consequences of duplicate genes. Science. 2000;290:1151–1155. doi: 10.1126/science.290.5494.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch M., Force A., Force A. The probability of duplicate gene preservation by subfunctionalization. Genetics. 2000;154:459–473. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.1.459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makinen M., Valtonen-Andre C., Lundwall A., Valtonen-Andre C., Lundwall A., Lundwall A. New World, but not Old World, monkeys carry several genes encoding beta-microseminoprotein. Eur. J. Biochem. 1999;264:407–414. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margulies E.H., Maduro V.V., Thomas P.J., Tomkins J.P., Amemiya C.T., Luo M., Green E.D., Maduro V.V., Thomas P.J., Tomkins J.P., Amemiya C.T., Luo M., Green E.D., Thomas P.J., Tomkins J.P., Amemiya C.T., Luo M., Green E.D., Tomkins J.P., Amemiya C.T., Luo M., Green E.D., Amemiya C.T., Luo M., Green E.D., Luo M., Green E.D., Green E.D. Comparative sequencing provides insights about the structure and conservation of marsupial and monotreme genomes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2005;102:3354–3359. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408539102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques-Bonet T., Navarro A., Navarro A. Chromosomal rearrangements are associated with higher rates of molecular evolution in mammals. Gene. 2005;353:147–154. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matassi G., Sharp P.M., Gautier C., Sharp P.M., Gautier C., Gautier C. Chromosomal location effects on gene sequence evolution in mammals. Curr. Biol. 1999;9:786–791. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(99)80361-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menten P., Wuyts A., Van Damme J., Wuyts A., Van Damme J., Van Damme J. Macrophage inflammatory protein-1. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:455–481. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen T.S., Wakefield M.J., Aken B., Amemiya C.T., Chang J.L., Duke S., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Wakefield M.J., Aken B., Amemiya C.T., Chang J.L., Duke S., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Aken B., Amemiya C.T., Chang J.L., Duke S., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Amemiya C.T., Chang J.L., Duke S., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Chang J.L., Duke S., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Duke S., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Garber M., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Gentles A.J., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Goodstadt L., Heger A., Heger A., et al. Genome of the marsupial Monodelphis domestica reveals innovation in non-coding sequences. Nature. 2007;447:167–177. doi: 10.1038/nature05805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montoya-Burgos J.I., Boursot P., Galtier N., Boursot P., Galtier N., Galtier N. Recombination explains isochores in mammalian genomes. Trends Genet. 2003;19:128–130. doi: 10.1016/S0168-9525(03)00021-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mouse Genome Sequencing Consortium. Initial sequencing and comparative analysis of the mouse genome. Nature. 2002;420:520–562. doi: 10.1038/nature01262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neves-Ferreira A.G., Cardinale N., Rocha S.L., Perales J., Domont G.B., Cardinale N., Rocha S.L., Perales J., Domont G.B., Rocha S.L., Perales J., Domont G.B., Perales J., Domont G.B., Domont G.B. Isolation and characterization of DM40 and DM43, two snake venom metalloproteinase inhibitors from Didelphis marsupialis serum. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2000;1474:309–320. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(00)00022-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilsson M.A., Arnason U., Spencer P.B., Janke A., Arnason U., Spencer P.B., Janke A., Spencer P.B., Janke A., Janke A. Marsupial relationships and a timeline for marsupial radiation in South Gondwana. Gene. 2004;340:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2004.07.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noyce L., Conaty J., Piper A.A., Conaty J., Piper A.A., Piper A.A. Identification of a novel tissue-specific processed HPRT gene and comparison with X-linked gene transcription in the Australian marsupial Macropus robustus. Gene. 1997;186:87–95. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(96)00686-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno S. Evolution by gene duplication. Springer-Verlag; Heidelberg, Germany: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T. Slightly deleterious mutant substitutions in evolution. Nature. 1973;246:96–98. doi: 10.1038/246096a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Pardo-Manuel Villena F., Sapienza C., Sapienza C. Female meiosis drives karyotypic evolution in mammals. Genetics. 2001;159:1179–1189. doi: 10.1093/genetics/159.3.1179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson W.R. Flexible sequence similarity searching with the FASTA3 program package. Methods Mol. Biol. 2000;132:185–219. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-192-2:185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piganeau G., Mouchiroud D., Duret L., Gautier C., Mouchiroud D., Duret L., Gautier C., Duret L., Gautier C., Gautier C. Expected relationship between the silent substitution rate and the GC content: Implications for the evolution of isochores. J. Mol. Evol. 2002;54:129–133. doi: 10.1007/s00239-001-0011-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poran N.S. Vomeronasal organ and its associated structures in the opossum Monodelphis domestica. Microsc. Res. Tech. 1998;43:500–510. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0029(19981215)43:6<500::AID-JEMT3>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna, Austria: 2006. http://www.R-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- Rat Genome Sequencing Project Consortium. Genome sequence of the Brown Norway rat yields insights into mammalian evolution. Nature. 2004;428:493–521. doi: 10.1038/nature02426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rens W., O’Brien P.C., Yang F., Solanky N., Perelman P., Graphodatsky A.S., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., O’Brien P.C., Yang F., Solanky N., Perelman P., Graphodatsky A.S., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Yang F., Solanky N., Perelman P., Graphodatsky A.S., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Solanky N., Perelman P., Graphodatsky A.S., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Perelman P., Graphodatsky A.S., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Graphodatsky A.S., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Ferguson M.W., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Svartman M., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., De Leo A.A., Graves J.A., Graves J.A., et al. Karyotype relationships between distantly related marsupials from South America and Australia. Chromosome Res. 2001;9:301–308. doi: 10.1023/a:1016646629889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samollow P.B. Status and applications of genomic resources for the gray, short-tailed opossum, Monodelphis domestica, an American marsupial model for comparative biology. Aust. J. Zool. 2006;54:173–196. [Google Scholar]

- Samollow P.B., Kammerer C.M., Mahaney S.M., Schneider J.L., Westenberger S.J., VandeBerg J.L., Robinson E.S., Kammerer C.M., Mahaney S.M., Schneider J.L., Westenberger S.J., VandeBerg J.L., Robinson E.S., Mahaney S.M., Schneider J.L., Westenberger S.J., VandeBerg J.L., Robinson E.S., Schneider J.L., Westenberger S.J., VandeBerg J.L., Robinson E.S., Westenberger S.J., VandeBerg J.L., Robinson E.S., VandeBerg J.L., Robinson E.S., Robinson E.S. First-generation linkage map of the gray, short-tailed opossum, Monodelphis domestica, reveals genome-wide reduction in female recombination rates. Genetics. 2004;166:307–329. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.1.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slater G.S., Birney E., Birney E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinformatics. 2005;6:31. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-6-31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonnhammer E.L., Koonin E.V., Koonin E.V. Orthology, paralogy and proposed classification for paralog subtypes. Trends Genet. 2002;18:619–620. doi: 10.1016/s0168-9525(02)02793-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streilein K.E. Behavior, ecology, and distribution of South American marsupials. In: Mares M.A., Genoways H.H., Genoways H.H., editors. Mammalian biology in South America. University of Pittsburgh; Philadelphia, PA: 1982a. pp. 231–250. [Google Scholar]

- Streilein K.E. Ecology of small mammals in the semiarid Brazilian Caatinga. I. Climate and faunal composition. Annals of Carnegie Museum. 1982b;51:79–107. [Google Scholar]

- Svartman M., Vianna-Morgante A.M., Vianna-Morgante A.M. Comparative genome analysis in American marsupials: Chromosome banding and in-situ hybridization. Chromosome Res. 1999;7:267–275. doi: 10.1023/a:1009274813921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson W.J., Vacquier V.D., Vacquier V.D. The rapid evolution of reproductive proteins. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2002;3:137–144. doi: 10.1038/nrg733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trott J.F., Wilson M.J., Hovey R.C., Shaw D.C., Nicholas K.R., Wilson M.J., Hovey R.C., Shaw D.C., Nicholas K.R., Hovey R.C., Shaw D.C., Nicholas K.R., Shaw D.C., Nicholas K.R., Nicholas K.R. Expression of novel lipocalin-like milk protein gene is developmentally-regulated during lactation in the tammar wallaby, Macropus eugenii. Gene. 2002;283:287–297. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00883-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel M.J., Guelen L., de Wit E., Peric-Hupkes D., Loden M., Talhout W., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Guelen L., de Wit E., Peric-Hupkes D., Loden M., Talhout W., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., de Wit E., Peric-Hupkes D., Loden M., Talhout W., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Peric-Hupkes D., Loden M., Talhout W., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Loden M., Talhout W., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Talhout W., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Feenstra M., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Abbas B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., Classen A.K., van Steensel B., van Steensel B. Human heterochromatin proteins form large domains containing KRAB-ZNF genes. Genome Res. 2006;16:1493–1504. doi: 10.1101/gr.5391806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webber C., Ponting C.P., Ponting C.P. Hotspots of mutation and breakage in dog and human chromosomes. Genome Res. 2005;15:1787–1797. doi: 10.1101/gr.3896805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wienberg J. The evolution of eutherian chromosomes. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2004;14:657–666. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2004.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe K.H., Sharp P.M., Li W.H., Sharp P.M., Li W.H., Li W.H. Mutation rates differ among regions of the mammalian genome. Nature. 1989;337:283–285. doi: 10.1038/337283a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodburne M.O., Rich T.H., Springer M.S., Rich T.H., Springer M.S., Springer M.S. The evolution of tribospheny and the antiquity of mammalian clades. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;28:360–385. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(03)00113-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Z. PAML: A program package for phylogenetic analysis by maximum likelihood. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1997;13:555–556. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/13.5.555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu L., Zhang Y.P., Zhang Y.P. The unusual adaptive expansion of pancreatic ribonuclease gene in carnivora. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2006;23:2326–2335. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msl101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J., Zhang Y.P., Rosenberg H.F., Zhang Y.P., Rosenberg H.F., Rosenberg H.F. Adaptive evolution of a duplicated pancreatic ribonuclease gene in a leaf-eating monkey. Nat. Genet. 2002;30:411–415. doi: 10.1038/ng852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuri I., Dombrowski K., Halpern M., Dombrowski K., Halpern M., Halpern M. Skin and gland but not urine odours elicit conspicuous investigation by female grey short-tailed opossums, Monodelphis domestica. Anim. Behav. 2005;69:635–642. [Google Scholar]