Abstract

Objective:

To describe the clinical characteristics, indications, technical procedures, and outcome of a consecutive series of laparoscopic distal pancreatic resections performed by the same surgical team.

Summary Background Data:

Laparoscopic distal pancreatic resection has increasingly been described as a feasible and safe procedure, although accompanied by a high rate of conversion and morbidity.

Methods:

A consecutive series of patients affected by solid and cystic tumors were selected prospectively to undergo laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy performed by the same surgical team. Clinical characteristics as well as diagnostic preoperative assessment and intra- and postoperative data were prospectively recorded. A follow-up of at least 3 months was available for all patients.

Results:

Fifty-eight patients underwent laparoscopic resection between May 1999 and November 2005. All procedures were successfully performed laparoscopically, and no patient required intraoperative blood transfusion. Splenic vessel preservation was possible in 84.4% of spleen-preserving procedures. There were no mortalities. The overall median hospital stay was 9 days, while it was 10.5 days for patients with postoperative pancreatic fistulae (27.5% of all cases). Follow-up was available for all patients.

Conclusions:

Our experience in 58 consecutive patients was characterized by the lack of conversions and by acceptable rates of postoperative pancreatic fistulae and morbidity. Laparoscopy proved especially beneficial in patients with postoperative complications as they had a relatively short hospital stay. Solid and cystic tumors of the distal pancreas represent a good indication for laparoscopic resection whenever possible.

Laparocopic distal pancreatectomy is increasingly used by many surgical teams. The major issues related to the technique are the conversion rate and postoperative complications. The authors describe their experience and discuss the indications, techniques, and results of 58 consecutive operations performed by the same surgical team with no conversions.

In the last few years, various attempts to treat pancreatic pathologies by a laparoscopic approach have been extended from diagnostic purposes to surgical intervention, giving rise to both bypass and resection procedures.1,2 At the same time, the increasingly frequent incidental diagnoses of cystic or, more rarely, solid and benign tumors in young individuals—mostly females—has led to an increasing demand for laparoscopic surgical procedures targeted at eradicating only the tumor while sparing the healthy spleen and pancreatic parenchyma and at minimizing the cosmetic impact of the surgical wound.

The first laparoscopic exploration on a pancreatic tumor was described by B.M. Bernheim of John Hopkins University in 1911, while the first laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy, on a pig, was described by Soper in 1994.3 In 1996, new prospects4 in pancreatic surgery were opened by Gagner who reported his initial experience on 5 cases of “spleen preserving” laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy for insulinoma. Since that time numerous small case reports or small series have appeared in the literature describing distal pancreatectomy for benign pathologies or low grade malignancies (insulinoma, chronic pancreatitis, cystadenoma). In addition a multicenter collected series has also been published.5

Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy raises two problems: sparing the spleen with or without ligation of the splenic vessels, and treating the pancreatic remnant. The latter is also an open challenge for a laparotomic approach. The purpose of this report was to document the results of our experience, which consists in 58 distal pancreatectomies (32 “spleen preserving”) performed by the same surgical team using a laparoscopic approach. To our knowledge, this is the largest patient cohort on this technique reported to date.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

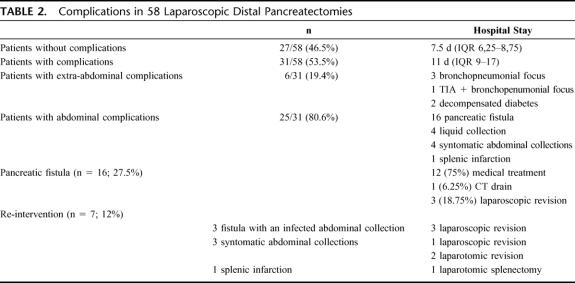

From May 1999 to November 2005, 58 patients (50 women and 8 men) with a median age of 48.9 years (interquartile range (IQR) 33.2–66.55) presenting localized tumors to the pancreatic body and tail were prospectively assessed and submitted to routine preoperative laboratory workup and imaging studies including ultrasonography, computerized tomography and/or Wirsung duct cholangiogram and abdominal MRI. After obtaining written consent, patients were submitted to the laparoscopic surgical procedure with radical intent. The procedure attempted to spare the spleen whenever possible. The operating times, use of blood transfusions, postoperative complications and distant follow-up (closed March 2006) were evaluated prospectively. Surgical complications were defined as shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1. Definitions of Abdominal Complications

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were described using the median value as a measure and the IQR as a measure of dispersion.

Technique

Position of the Patient, Surgeons, and Trocars

The patient was placed in a supine position with his/her legs apart. The operating table allowed changing the patient's position easily: a slight (35°) anti-Trendelenburg tilt was obtained and if necessary rotated about 30° to the right. A gastric tube and a bladder catheter were inserted. The surgeon stood between the legs of the patient, while the first and second assistants, respectively, stood on the left and right of the operating surgeon. The scrub nurse was on the right side of the operating surgeon. The monitor was placed over the left shoulder of the patient.

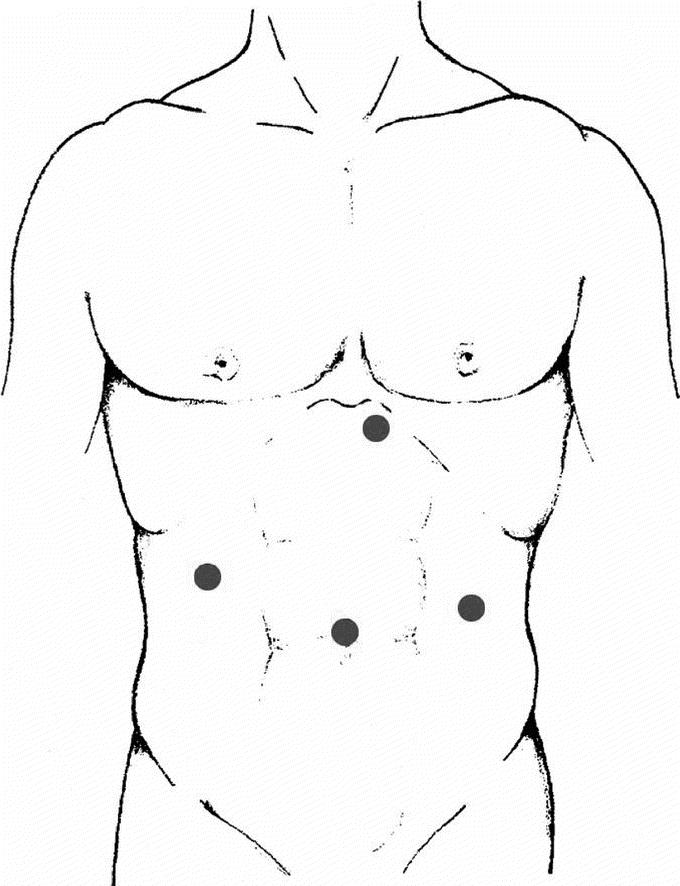

A Veress needle was inserted in the left subcostal area to induce pneumoperitoneum. The intra-abdominal pressure was monitored and maintained at around 12 mmHg. The first trocar—preferably optical—was inserted in the umbilicus. The remaining trocars were placed as follows: 1 (5 mm) left paraxiphoid, 1 (5–12 mm) in the right subcostal area, 1 (5–12 mm) in the left side (Fig. 1). The 30° angled scopes were inserted through the umbilical trocar. The operating surgeon used the instruments placed in the right subcostal area and in the left side. In one case the patient laid on his right side, and the trocars were positioned in the same manner as for left adrenalectomy.

FIGURE 1. Positioning of trocars.

Exploration of the Pancreas

The pancreas was explored through the infragastric access. Using an atraumatic grasper introduced through the left paraxiphoid trocar, the assistant grasped the stomach at the great curvature and raised it. The operating surgeon used an ultrasound dissector or a bipolar vessel sealing device to open a window in the gastrocolic ligament, below the gastroepiploic arch; the window was then enlarged to expose the pancreas. If the spleen was to be spared, the enlargement was stopped at the first short gastric vessel. A linear (10 mm) multifrequency (5–7.5 MHz) laparoscopic ultrasound probe with steerable head (revolving at 90°–180°, up/down, right/left) was introduced and brought into contact with the anterior surface of the pancreas, to facilitate its exploration and to identify small deep lesions or to clarify the connection of the lesion with the Wirsung duct or the splenomesenteric vessels.

“Spleen Preserving” Distal Pancreatectomy Sparing the Splenic Vessels

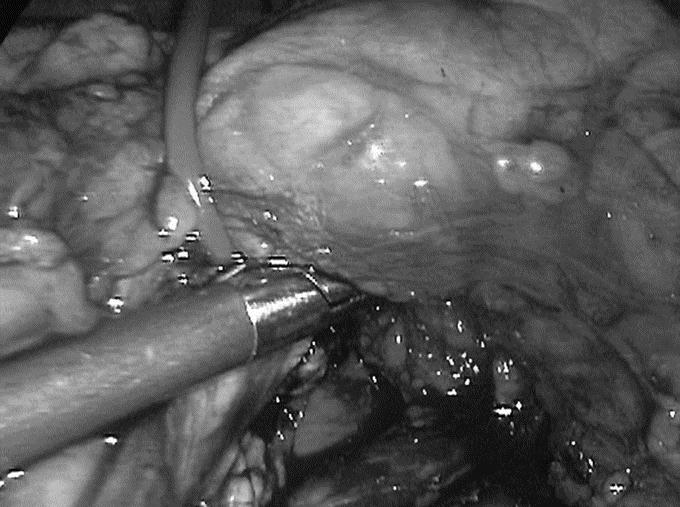

The dissection began at the inferior margin of the body of the pancreas (left of the upper mesenteric vein) at the attachment of the root of the transverse mesocolon moving toward the tail, looking for the splenic vein. Once identified, the splenic vein is dissected from the pancreas. The small pancreatic vein branches are easily coagulated; clips are rarely necessary and are only needed for veins with a lumen greater than 5 mm (Fig. 2).

FIGURE 2. Dissection of the splenic vein from the pancreas. The small pancreatic vein branches are easily coagulated.

Next the tail of the pancreas was mobilized and retracted medially. A “no-touch” technique is used, whereby the tools come into contact only with the peripancreatic fat. Further dissection of the posterior pancreatic surface allows unimpeded view of the splenic vessels. The splenic artery is generally dissected in the direction opposite to the vein. This maneuver is generally easier because the walls are firmer. Whenever necessary, it was possible to extend vascular dissection medially beyond the confluence of the splenomesenteric-portal veins.

The pancreas is divided with a mechanic stapler thus ensuring good hemostasis and tight closure of Wirsung's duct. At the beginning we used a stapler with 3.5-mm staples, although we now prefer a stapler carrying 4.5-mm staples. It is also possible to section the parenchyma using only a bipolar vessel sealing device. Any bleeding due to sectioning is treated with uni/bipolar coagulation.

The surgical specimen is removed in a special bag. The minilaparotomy can be carried out at the umbilical port, or at the 12-mm trocar port used to introduce the mechanical stapler (left side) or suprapubically for cosmetic reasons. A laminar soft drain is left adjacent to the pancreatic remnant.

“Spleen-Preserving” Distal Pancreatectomy With Splenic Vessel Ligature

This technique entails the ligature and proximal and distal sectioning of the splenic artery and vein. The spleen is vascularized through the short gastric vessels and the splenocolic ligament. We used this technique only following accidental intraoperative injury to the splenic artery or vein or whenever the vessels could not be separated from the tumor.

Distal Splenopancreatectomy

First, a subpancreatic tunnel is opened at the isthmus. The splenic vein and artery are dissected and sectioned between clips or with a vascular endostapler. If the vessels could not be dissected from the pancreatic parenchyma, they could be dissected en bloc together with the parenchyma, using at least 2 mechanical stapler fires. Once the pancreatic remnant was dissected, the spleen was mobilized by sectioning the suspending ligaments. The ablated specimen was placed in a large bag (15 mm) whose opening is secured to a minilaparotomy, so that the spleen could be partially morcellated and the tail of the pancreas could be ablated intact.

RESULTS

All 58 surgical procedures were completed using the laparoscopic approach. The median operative time was 165 minutes (IQR 120–200). No intraoperative blood transfusions were needed. Of the 58 interventions, there were 32 (55.1%) distal “spleen preserving” pancreatectomies (31 with the patient lying supine and 1 with the patient lying on his right side), and 26 (44.9%) distal splenopancreatectomies with the patient lying supine. The median operative time was 152.5 minutes for the former group (IQR 120–180) and 197.5 minutes for the latter (IQR 150–225). In 55 cases the parenchyma was divided with a mechanical stapler: in 7 of these cases the mechanical suture line was protected with a slow-reabsorption reinforcing membrane (Seamguard®, Gore-Tex). A bipolar vessel sealing device (10 mm) was used in the 3 remaining cases. In the splenopancreatectomy group, 1 patient underwent right adrenalectomy with an anterior approach for a 7-cm adrenocortical tumor, 1 had enucleation of a left kidney tumor and a third patient underwent left nephrectomy for a 3-cm hilar solid kidney mass that had been diagnosed as renal infarction. In the distal pancreatectomy group, left adrenalectomy was performed in only one case for an adrenal pseudocyst. Five of the 32 (15.6%) patients who underwent the “spleen preserving” intervention needed ligature of the splenic vessels.

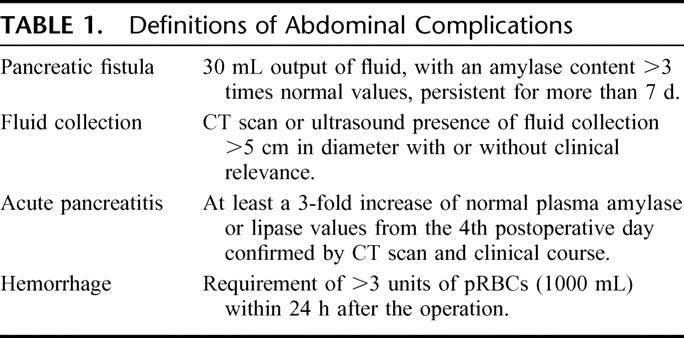

No case of perioperative mortality was recorded. The median length of hospital stay was 9 days for the 58 patients (IQR 7–12.5). For 27 of 58 patients (46.5%) the postoperative course was uneventful with a median length of hospital stay of 7.5 days (IQR 6.25–8.75). Of the 31 patients with postoperative complications, [median postoperative length of hospital stay 11 days (IQR 9–17)], 6 had nonsurgical complications: 4 of these had a pneumonia focus and 1 was affected by a TIA, while decompensated diabetes developed in 2 patients.

Abdominal complications were recorded in 25 patients (43%). A pancreatic fistula was diagnosed in 16 patients (27.5% of the 58 patients), which was treated on an out-patient basis in 12 cases and resolved within 1 month from surgery. In the remaining 4 patients, the fistula resulted in an infected abdominal collection, which was treated with a CT-guided percutaneous drain in 1 case, while laparoscopic revision was necessary in the other 3 to drain the peritoneal cavity.

Postoperative fluid collections were detected in 8 patients. In 4 patients the fluid collections were asymptomatic and resolved spontaneously. In the other 4 patients treatment was required. In 1 case CT-guided drainage resulted in resolution. Three patients with symptomatic abdominal collections required surgical intervention. A laparoscopic drainage procedure was accomplished in 1 patient where an open drainage was required in the remaining two. The amylase level in the drainage fluid was within normal limits in all patients. One patient subjected to spleen-preserving pancreatectomy with splenic vessel ligature developed splenic infarction and underwent splenectomy 9 days after the first procedure. Overall, 7 patients (12%) required reoperation with 4 of the procedures performed via a laparoscopic approach. Five of these second operations occurred during the initial period of our experience.

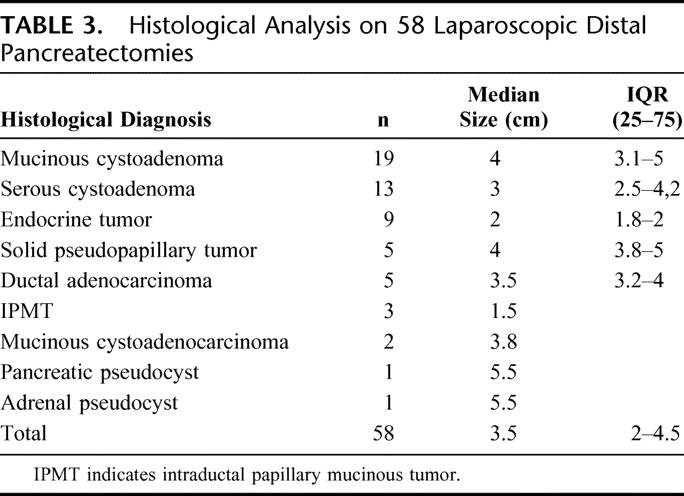

Table 2 summarizes the complications observed, while histologic diagnosis is shown in Table 3. All 5 ductal adenocarcinomas were analyzed intraoperatively and all had negative resection margins. The median number of nodes in the specimens was 13 with a median of 4 positive nodes. All the patients are alive and free from disease at a median follow-up of 26 months (IQR 18–43.5), except 1 patient suffering from pancreatic adenocarcinoma who died 3 months after the radical procedure due to myocardial infarction. Two patients developed trocar incisional hernia successfully treated with laparoscopic prosthetic repair; 1 patient had a long-standing symptomatic pancreatic pseudocyst that was endoscopically drained 6 months after pancreatectomy.

TABLE 2. Complications in 58 Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomies

TABLE 3. Histological Analysis on 58 Laparoscopic Distal Pancreatectomies

DISCUSSION

The traditional surgical approach to the distal pancreas requires large abdominal incisions because of the particularly deep position of this gland, and entails possible postoperative complications such as wound infections and incisional hernia, in addition to the obvious functional and cosmetic impairments. Furthermore, the most frequent histotypes of resectable distal pancreatic tumors are currently cystic and endocrine neoplasms, which are often benign and usually diagnosed incidentally during ultrasound examinations carried out in young women. Therefore, the laparoscopic technique is becoming increasingly popular among surgeons to perform distal pancreatectomy.

The most widespread technique is prograde pancreatectomy performed by transecting the pancreatic body first and then moving up towards the spleen.5 Our technique consists of a retrograde pancreatectomy with initial mobilization of the pancreatic body and dissection of the inferior margin of the gland to look for the splenic vein. As soon as the vein is identified, it is important to separate it from the parenchyma with an ultrasonic device or clips if needed, going up to the splenic hilum. This is the most risky step because of the relative fragility of the splenic vein branches. The good result of our experience in terms of conversion rate, which was nil compared with conversion rates ranging from 5 to 43%4–11 in the largest case series (>10 cases), led us to improve this approach in all patients to prevent intraoperative bleeding and to spare as much pancreatic parenchyma as possible.

Furthermore, in the spleen preserving procedures, the splenic vessels could be spared in 84.4% of our cases, which is an obvious advantage for splenic vascularization. Although spleen preservation is feasible even when the splenic vessels are killed,12–16 their preservation reduces the risk of abscesses or splenic infarction,17 which was experienced in 1 patient. We prefer to have the patient in the supine position during the intervention, which allows a routine anatomic approach to the retrogastric cavity. The right lateral position and the initial mobilization of the spleen do not facilitate the surgical maneuvers of splenic vessel isolation and dissection. On the other hand, the semilateral right position (30°) can be helpful if, from the onset of the procedure, the aim is distal splenopancreatectomy.

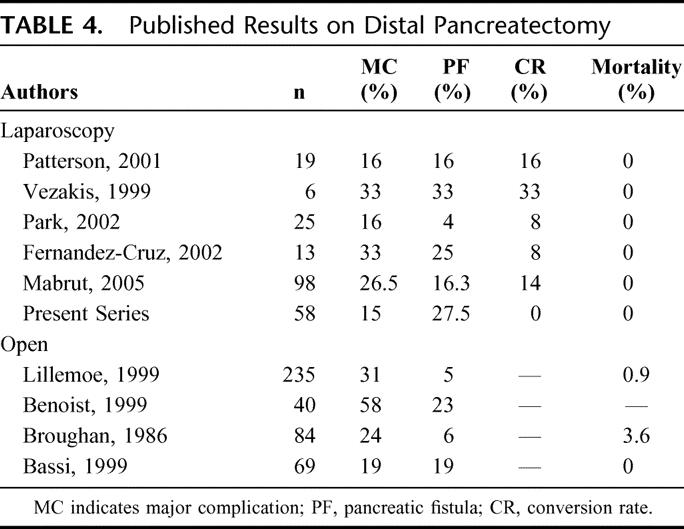

As in open resections, the major challenge is still management of the pancreatic stump: both the literature data and this series show that the laparoscopic approach presents the same high risk of postoperative pancreatic fistula with all possible complications (Table 4).18–20,21 The formation of fistulae is strictly due to the soft tissue typical of the residual pancreas of patients suffering from cystic or endocrine benign tumors, as in the present series. In our experience the best technique to cut the pancreas is using the linear stapler. During our initial experience we used 3.5-mm staples before changing to 4.5-mm staples to prevent ischemia of the pancreatic stump and reduce fistula formation. In 7 patients treated with a linear stapler associated with Seamguard®, we obtained a good postoperative course without fistula.

TABLE 4. Published Results on Distal Pancreatectomy

A bipolar vessel sealing device was used to divide the pancreas in 3 cases as described by Matsumoto.22 In our hands this technique resulted in pancreatic fistula in 1 case and abdominal fluid collection in another, and therefore this technique was abandoned due to this high complication rate.

In a series of 69 patients prospectively enrolled in a randomized trial on the management of the pancreatic stump after distal open resection,21 the overall fistula rate was 19% using the same definition applied to the present series and the reoperation rate was also lower (3% vs. 12%). Perhaps the most interesting observation is that the median postoperative hospital stay in the group of patients with complications decreased from 29 to 11 days in the laparoscopic group, leading us to believe that despite complications, patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery have shorter hospital stays and recover more quickly. With regards to the indications for a laparoscopic approach, almost all our patients were preoperatively identified as suffering from a benign tumor. The indication to surgery of 13 serous cystadenomas was supported by abdominal symptoms in 7 patients and the impossibility to distinguish between mucinous and serous neoplasms in preoperative assessment of the remaining 6 due to macrocystic morphology. In 2 cases with a preoperative diagnosis of mucinous cystadenoma the histology was consistent with a pancreatic pseudocyst in 1 case and an adrenal pseudocyst in the other. In the most recent period we have resected 5 ductal cancers with an excellent postoperative course. Even though still controversial, laparoscopic resection of ductal carcinomas in our experience was safe and oncologically correct with disease-free resection margins and a median of 13 removed lymph nodes. Nevertheless the follow-up is still too short to draw definitive conclusions for this particular histotype and laparoscopic resection.

In conclusion, the main results of our experience are: 1) a conversion rate of 0% without intraoperative blood transfusions; 2) high percentage (84.4%) of splenic vessel preservation during spleen-preserving procedures; 3) median operative time of 165 minutes; and 4) median postoperative hospital stay of 11 days in 43% of patients suffering from any abdominal complications.

CONCLUSIONS

The advantage of laparoscopy in the management of distal pancreatic tumors is represented by the high quality of vision, which makes it possible to maximize the percentage of spleen preserving, vessel preserving procedures while lowering postoperative complications such as splenic infarction and abscesses. Furthermore patients who experienced a postoperative complication had a short hospital stay and could be treated on an outpatient basis. The conversion rate of zero represents a particularly interesting result of the present series. The challenge for both the laparoscopic and the “open” pancreatic surgeons is still the management of the pancreatic stump to avoid postoperative fistulae.

Footnotes

Supported by Ministeri Università e Salute, Rome, Italy; Fondazione Cassa di Risparmio di Verona (Bando 2004) and Fondazione Giorgio Zanotto, Verona, Italy.

Reprints: Giovanni Butturini, MD, PhD. Surgical and Gastroenterological Science Department, Verona University. Piazzale LA Scuro, 10 37134 Verona, Italy, E-mail: giovanni.butturini@univr.it.

REFERENCES

- 1.Underwood RA, Soper NJ. Current status of laparoscopic surgery of the pancreas. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 1999;6(2):154–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melotti G, Piccoli M. Pancreas e laparoscopia. Con la telecamera dove sembra impossibile. Osp Ital Chir. 2000;6:331–332. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Soper NJ, Brunt LM, Dunnegan DL, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy in the porcine model. Surg Endosc. 1994;8:57–60; Discussion 60–1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Gagner M, Pomp A, Herrera MF. Early experience with laparoscopic resections of islet cell tumors. Surgery. 1996;120:1051–1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mabrut JY, Fernandez-Cruz L, Azagra JS, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: results of a multicenter European study of 127 patients. Surgery. 2005;137:597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dulucq JL, Wintringer P, Stabilini C, et al. Are major laparoscopic pancreatic resections worthwhile? A prospective study of 32 patients in a single institution. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:1028–1034. 11. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Fabre JM, Dulucq JL, Vacher C, et al. Is laparoscopic left pancreatic resection justified? Surg Endosc. 2002;16:1358–1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fernandez-Cruz L, Saenz A, Astudillo E, et al. Outcome of laparoscopic pancreatic surgery: endocrine and nonendocrine tumors. World J Surg. 2002;26:1057–1065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park AE, Heniford BT. Therapeutic laparoscopy of the pancreas. Ann Surg. 2002;236:149–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patterson EJ, Gagner M, Salky B, et al. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection: single-institution experience of 19 patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;193:281–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gentileschi P, Gagner M. Laparoscopic pancreatic resection. Chir Ital. 2001;53:279–289. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Warshaw AL. Conservation of the spleen with distal pancreatectomy. Arch Surg. 1988;123:550–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pradere B, Julio CH, Rimailho J, et al. Left pancreatectomy with preservation of the spleen without its pedicle. Apropos of 13 cases. Ann Chir. 1992;46:620–624. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tihanyi TF, Morvay K, Nehez L, et al. Laparoscopic distal resection of the pancreas with the preservation of the spleen. Acta Chir Hung. 1997;36:359–361. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vezakis A, Davides D, Larvin M, et al. Laparoscopic surgery combined with preservation of the spleen for distal pancreatic tumors. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:26–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ueno T, Oka M, Nishihara K, et al. Laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy with preservation of the spleen. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 1999;9:290–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kimura W, Inoue T, Futakawa N, et al. Spleen-preserving distal pancreatectomy with conservation of the splenic artery and vein. Surgery. 1996;120:885–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lillemoe KD, Kaushal S, Cameron JL, et al. Distal pancreatectomy: indications and outcomes in 235 patients. Ann Surg. 1999;229:693–698; discussion 698–700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Benoist S, Dugue L, Sauvanet A, et al. Is there a role of preservation of the spleen in distal pancreatectomy? J Am Coll Surg. 1999;188:255–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Broughan TA, Leslie JD, Soto JM, et al. Pancreatic islet cell tumors. Surgery. 1986;99:671–678. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassi C, Butturini G, Falconi M, et al. Prospective randomised pilot study of management of the pancreatic stump following distal resection. HPB. 1999;1:203–207. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Matsumoto T, Kitano S, Yoshida T, et al. Laparoscopic resection of a pancreatic mucinous cystadenoma using laparosonic coagulating shears. Surg Endosc. 1999;13:172–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]