Abstract

In response to nitrogen starvation, the human fungal pathogen Candida albicans switches from yeast to filamentous growth. This morphogenetic switch is controlled by the ammonium permease Mep2p, whose expression is induced under limiting nitrogen conditions. In order to understand in more detail how nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth is regulated in C. albicans, we identified the cis-acting sequences in the MEP2 promoter that mediate its induction in response to nitrogen limitation. We found that two putative binding sites for GATA transcription factors have a central role in MEP2 expression, as deletion of the region containing these sites or mutation of the GATAA sequences in the full-length MEP2 promoter strongly reduced MEP2 expression. To investigate whether the GATA transcription factors GLN3 and GAT1 regulate MEP2 expression, we constructed mutants of the C. albicans wild-type strain SC5314 lacking one or both of these transcription factors. Expression of Mep2p was strongly reduced in gln3Δ and gat1Δ single mutants and abolished in gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants. Deletion of GLN3 strongly inhibited filamentous growth under limiting nitrogen conditions, but the filamentation defect of gln3Δ mutants could be rescued by constitutive expression of MEP2 from the ADH1 promoter. In contrast, inactivation of GAT1 had no effect on filamentation, and we found that filamentation became independent of the presence of a functional MEP2 gene in the gat1Δ mutants, indicating that the loss of GAT1 function results in the activation of other pathways inducing filamentous growth. These results demonstrate that the GATA transcription factors GLN3 and GAT1 control expression of the MEP2 ammonium permease and that GLN3 is also an important regulator of nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth in C. albicans.

The yeast Candida albicans is a member of the microflora on mucosal surfaces of most healthy people, but it can also cause serious infections, especially in immunocompromised patients (20). Under various environmental conditions, e.g., an increase in temperature and pH, the presence of serum, or nutrient starvation, C. albicans switches from yeast to filamentous growth, and this capacity is considered important for the virulence of the fungus (15, 23, 25). Therefore, how C. albicans senses and transduces environmental signals that induce morphogenesis has been a major focus of research in the past years (5, 6, 14, 24).

One of the conditions that promote filamentation is growth on solid media in which nitrogen sources are present at limiting concentrations. In response to nitrogen starvation, C. albicans expresses the MEP1 and MEP2 genes, which encode ammonium transporters that enable growth of the fungus when ammonium at limiting concentrations is the only available nitrogen source (2). While deletion of either one of these two ammonium permeases does not affect the ability of C. albicans to grow at low ammonium concentrations, mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants are unable to grow under these conditions. In addition to being an ammonium transporter, Mep2p is involved in the control of morphogenesis, as mep2Δ mutants do not switch to filamentous growth under limiting nitrogen conditions, while mep1Δ mutants behave like the wild type. The functions of the C. albicans ammonium permeases are similar to those of their counterparts in the model yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which possesses three genes encoding ammonium permeases that mediate ammonium uptake into the cell (18). S. cerevisiae also differentiates into a filamentous, pseudohyphal growth form under nitrogen starvation conditions, which is thought to enable these nonmotile organisms to seek a preferable environment (9). Deletion of MEP2, but not of MEP1 or MEP3, abolishes the pseudohyphal growth of S. cerevisiae in response to low ammonium concentrations, although mep2Δ mutants are not defective in ammonium uptake or growth under these conditions (16). The filamentation defect of S. cerevisiae mep2Δ mutants is limited to growth under low-ammonium conditions, and the mutants exhibit normal pseudohyphal growth when other nitrogen sources are limiting. In contrast, in C. albicans, Mep2p has a more central role in the control of morphogenesis, as C. albicans mep2Δ mutants have a filamentous growth defect under limiting nitrogen conditions, irrespective of the nature of the nitrogen source (2). However, MEP2 is not required for filamentous growth of C. albicans in response to other inducing signals, e.g., in the presence of serum. It was found that the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail of Mep2p, which is dispensable for ammonium transport, has a specific signaling function, as its deletion abolished the ability of the ammonium permease to induce filamentous growth without affecting ammonium uptake. The ability of a hyperactive, overexpressed MEP2ΔC440 allele to overcome the filamentous growth defect of cph1Δ and efg1Δ single mutants, but not that of cph1Δ efg1Δ double mutants, suggested that Mep2p normally activates both the Cph1p-dependent mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway and the Efg1p-dependent cyclic AMP/protein kinase A pathway to induce filamentous growth in response to nitrogen starvation (2).

Among the distinguishing features of MEP1 and MEP2 are their expression levels. Both ammonium permeases are induced in response to nitrogen limitation, but Mep2p is expressed at much higher levels than Mep1p. Promoter-swapping experiments demonstrated that the differential expression levels are due to the stronger activity of the MEP2 promoter than that of the MEP1 promoter and presumably also to differential transcript stability (2). Expression of MEP2 from the MEP1 promoter resulted in reduced amounts of Mep2p, inefficient ammonium transport, and the loss of its ability to induce filamentous growth. In contrast, the expression of MEP1 from the MEP2 promoter resulted in increased Mep1p levels, which also conferred on it the ability to induce a weak filamentation. These results demonstrated that Mep1p is a highly efficient ammonium transporter that needs to be expressed only at low levels to support growth on limiting ammonium concentrations, while Mep2p is a less efficient ammonium transporter that is expressed at high levels, which in turn is a prerequisite for the induction of filamentation.

Since the control of MEP2 expression is central to the regulation of nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth in C. albicans, we set out to identify the cis-acting sequences in the MEP2 promoter as well as the trans-acting regulatory factors involved in the induction of MEP2 expression and to elucidate their roles in morphogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions.

C. albicans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. All strains were stored as frozen stocks with 15% glycerol at −80°C. Strains were propagated on synthetic dextrose (SD) agar plates (6.7 g yeast nitrogen base without amino acids [YNB; Bio101, Vista, CA], 20 g glucose, 15 g agar per liter). For routine growth of the strains, YPD liquid medium (20 g peptone, 10 g yeast extract, 20 g glucose per liter) was used. To support the growth of ura3 strains, 100 μg·ml−1 uridine was added to the media. To observe MEP2 expression, strains were grown overnight in liquid SD-Pro medium (which contains 0.1% proline instead of ammonium), diluted 50-fold, and grown for 6 h at 30°C in SD medium containing 100 μM ammonium or other nitrogen sources as indicated in the text. Growth of mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants expressing MEP2-GFP from wild-type and mutated MEP2 promoters was tested on SD 2% agar plates containing 1 mM ammonium. To study filamentation and Mep2p expression on solid media, the strains were grown as single colonies for 6 days at 37°C on SD 2% agar plates containing 100 μM ammonium or other nitrogen sources as described in the text. Filamentation was also tested on agar plates containing 10% fetal calf serum.

TABLE 1.

C. albicans strains used in this study

| Strain(s) | Parent strain | Relevant genotype or characteristica | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|---|

| SC5314 | Wild-type strain | 8 | |

| CAI4 | SC5314 | ura3Δ::imm434/ura3Δ::imm434 | 7 |

| CAI4RU1A and CAI4RU1B | CAI4 | ura3Δ::imm434/URA3 | This study |

| mep2Δ single and mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants | |||

| SCMEP2M1A | SC5314 | mep2-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/MEP2-2 | This study |

| SCMEP2M1B | SC5314 | MEP2-1/mep2-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| SCMEP2M2A | SCMEP2M1A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/MEP2-2 | This study |

| SCMEP2M2B | SCMEP2M1B | MEP2-1/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| SCMEP2M3A | SCMEP2M2A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| SCMEP2M3B | SCMEP2M2B | mep2-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| SCMEP2M4A | SCMEP2M3A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| SCMEP2M4B | SCMEP2M3B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2M4A and MEP2M4B | CAI4 | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT | 2 |

| MEP2M4RU1A | MEP2M4A | ura3Δ::imm434/URA3 mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2M4RU1B | MEP2M4B | ura3Δ::imm434/URA3 mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12M4A and MEP12M4B | CAI4 | mep1-1Δ::FRT/mep1-2Δ::FRT mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT | 2 |

| MEP12M6A | MEP12M4A | mep1-1Δ::FRT/mep1-2Δ::FRT mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::URA3 | 2 |

| MEP12M6B | MEP12M4B | mep1-1Δ::FRT/mep1-2Δ::FRT mep2-1Δ::URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | 2 |

| Strains expressing a MEP2-GFP fusion under the control of wild-type and mutated MEP2 promoters in a mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutant background | |||

| MEP12MG6A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP1A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ1-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP1B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ1-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP2A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ2-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP2B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ2-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP3A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ3-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP3B | MEP12M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ3-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP4A | MEP12M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ4-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP4B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ4-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP5A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ5-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP5B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ5-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP6A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ6-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP6B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ6-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP7A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ7-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6ΔP7B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ7-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6MP1A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2M1-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6MP1B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2M1-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| MEP12MG6MP2A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2M2-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6MP2B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2M2-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6MP3A | MEP12M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2M3-MEP2-GFP-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP12MG6MP3B | MEP12M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2M3-MEP2-GFP-URA3 | This study |

| Strains expressing MEP2 under the control of wild-type and mutated MEP2 promoters in a mep2Δ background | |||

| MEP2MK13A | MEP2M4A | mep2-1::PMEP2-MEP2-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2MK13B | MEP2M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-URA3 | This study |

| MEP2MK13ΔP5A | MEP2M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ5-MEP2-URA3 | This study |

| MEP2MK13ΔP5B | MEP2M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ5-MEP2-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2MK13ΔP6A | MEP2M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2Δ6-MEP2-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2MK13ΔP6B | MEP2M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2Δ6-MEP2-URA3 | This study |

| MEP2MK13MP1A | MEP2M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2M1-MEP2-URA3 | This study |

| MEP2MK13MP1B | MEP2M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2M1-MEP2-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2MK13MP2A | MEP2M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2M2-MEP2-URA3 | This study |

| MEP2MK13MP2B | MEP2M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2M2-MEP2-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| MEP2MK13MP3A | MEP2M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2::PMEP2M3-MEP2-URA3 | This study |

| MEP2MK13MP3B | MEP2M4B | mep2-1::PMEP2M3-MEP2-URA3/mep2-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| gln3Δ mutants and complemented strains | |||

| GLN3M1A | SC5314 | gln3-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/GLN3-2 | This study |

| GLN3M1B | SC5314 | GLN3-1/gln3-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| GLN3M2A | GLN3M1A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/GLN3-2 | This study |

| GLN3M2B | GLN3M1B | GLN3-1/gln3-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GLN3M3A | GLN3M2A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| GLN3M3B | GLN3M2B | gln3-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/gln3-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GLN3M4A | GLN3M3A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GLN3M4B | GLN3M3B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GLN3MK1A | GLN3M4A | GLN3-SAT1-FLIP/gln3-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GLN3MK1B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/GLN3-SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| GLN3MK2A | GLN3MK1A | GLN3-FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GLN3MK2B | GLN3MK1B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/GLN3-FRT | This study |

| gat1Δ mutants | |||

| GAT1M1A | SC5314 | gat1-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/GAT1-2 | This study |

| GAT1M1B | SC5314 | GAT1-1/gat1-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| GAT1M2A | GAT1M1A | gat1-1Δ::FRT/GAT1-2 | This study |

| GAT1M2B | GAT1M1B | GAT1-1/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GAT1M3A | GAT1M2A | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| GAT1M3B | GAT1M2B | gat1-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GAT1M4A | GAT1M3A | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| GAT1M4B | GAT1M3B | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants and complemented strains | |||

| Δgln3GAT1M1A | GLN3M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/GAT1-2 | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M1B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT GAT1-1/gat1-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M2A | Δgln3GAT1M1A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/GAT1-2 | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M2B | Δgln3GAT1M1B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT GAT1-1/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M3A | Δgln3GAT1M2A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M3B | Δgln3GAT1M2B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M4A | Δgln3GAT1M3A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1M4B | Δgln3GAT1M3B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1MK1A | Δgln3GAT1M4A | GLN3-SAT1-FLIP/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1MK1B | Δgln3GAT1M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/GLN3-SAT1-FLIP gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1MK2A | Δgln3GAT1MK1A | GLN3-FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δgln3GAT1MK2B | Δgln3GAT1MK1B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/GLN3-FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| mep2Δ gat1Δ double mutants | |||

| Δmep2GAT1M1A | SCMEP2M4A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT GAT1-1/gat1-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M1B | SCMEP2M4B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/GAT1-2 | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M2A | Δmep2GAT1M1A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT GAT1-1/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M2B | Δmep2GAT1M1B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/GAT1-2 | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M3A | Δmep2GAT1M2A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::SAT1-FLIP/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M3B | Δmep2GAT1M2B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::SAT1-FLIP | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M4A | Δmep2GAT1M3A | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Δmep2GAT1M4B | Δmep2GAT1M3B | mep2-1Δ::FRT/mep2-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT | This study |

| Strains expressing MEP2-GFP or MEP1-GFP fusions in wild-type and mutant backgrounds | |||

| SCMEP2G7A | SC5314 | mep2-1::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1/MEP2-2 | This study |

| SCMEP2G7B | SC5314 | MEP2-1/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP2G7A | GLN3M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT mep2-1::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1/MEP2-2 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP2G7B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT MEP2-1/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgat1MEP2G7A | GAT1M4A | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP2-1/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgat1MEP2G7B | GAT1M4B | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT mep2-1::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1/MEP2-2 | This study |

| Δgln3Δgat1MEP2G7A | Δgln3GAT1M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP2-1/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3Δgat1MEP2G7B | Δgln3GAT1M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP2-1/mep2-2::PMEP2-MEP2-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMEP1G4A and SCMEP1G4B | SC5314 | MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP1G4A | GLN3M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP1G4B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgat1MEP1G4A | GAT1M4A | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgat1MEP1G4B | GAT1M4B | gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3Δgat1MEP1G4A | Δgln3GAT1M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3Δgat1MEP1G4B | Δgln3GAT1M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT gat1-1Δ::FRT/gat1-2Δ::FRT MEP1/mep1::PMEP1-MEP1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Strains expressing wild-type and hyperactive MEP2 alleles from the ADH1 promoter or carrying a control construct in wild-type and gln3Δ backgrounds | |||

| SCADH1G4A and SCADH1G4B | SC5314 | ADH1/adh1::PADH1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMEP2E4A and SCMEP2E4B | SC5314 | ADH1/adh1::PADH1-MEP2-caSAT1 | This study |

| SCMEP2ΔC2E2A and SCMEP2ΔC2E2B | SC5314 | ADH1/adh1::PADH1-MEP2ΔC440-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3ADH1G4A | GLN3M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3ADH1G4B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-GFP-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP2E4A | GLN3M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-MEP2-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP2E4B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-MEP2-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP2ΔC2E2A | GLN3M4A | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-MEP2ΔC440-caSAT1 | This study |

| Δgln3MEP2ΔC2E2B | GLN3M4B | gln3-1Δ::FRT/gln3-2Δ::FRT ADH1/adh1::PADH1-MEP2ΔC440-caSAT1 | This study |

SAT1-FLIP denotes the SAT1 flipper cassette.

Plasmid constructions. (i) Plasmids containing a GFP-tagged or wild-type MEP2 gene under the control of wild-type and mutated MEP2 promoters.

Plasmid pMEP2G6, which contains a green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged MEP2 gene under the control of the wild-type MEP2 promoter and served as the basis for the introduction of deletions and mutations in the MEP2 regulatory region (see Fig. 1), was generated in the following way. A KpnI-XhoI fragment containing MEP2 upstream sequences from positions −1478 to −5 with respect to the start codon was amplified from genomic DNA of C. albicans strain SC5314 with the primers MEP44 (5′-CAGCTATCTTGGTaCCTCATCAATCAATTGC-3′) and MEP24 (5′-CCAGACActcgaGTTATTAACTATTCAGAG-3′) (the lowercase letters here and below represent nucleotide exchanges introduced to create the underlined restriction sites [here, KpnI and XhoI]). The MEP2 promoter fragment was then cloned together with an XhoI-BamHI fragment from plasmid pMEP2G5 (2) containing the MEP2 coding region into KpnI/BamHI-digested pMEP2G2 (2). The cloned MEP2 promoter fragment contained the polymorphic EcoRI site, which is present only in the MEP2-1 allele (2). To construct pMEP2ΔP1, a distal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −1478 to −1015) was amplified with the primer pair MEP44 and MEP55 (5′-TCCTCGTTCTAgATACTAATGGTTGATACG-3′), and a proximal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −188 to −5) was amplified with the primer pair MEP51 (5′-GAAAAATCTagaAATCCCTATTGTGATTGG-3′) and MEP24. The PCR products were digested with KpnI/XbaI and XbaI/XhoI, respectively, and cloned together into KpnI/XhoI-digested pMEP2G6. To create pMEP2ΔP2, a proximal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −431 to −5) was amplified with the primer pair MEP52 (5′-AACCACtctAGATTTACCCCACTTCG-3′) and MEP24 and substituted for the XbaI-XhoI fragment in pMEP2ΔP1. Additional deletion constructs were made in an analogous fashion. Proximal MEP2 promoter fragments from positions −620 to −5, −805 to −5, −287 to −5, and −217 to −5 were amplified with the primer pairs MEP53 (5′-GTGATGCTCtagATAAATACAATACCCAAACG-3′) and MEP24, MEP54 (5′-ATGATTTTCTaGaATATACCATGAAGTACCAAGC-3′) and MEP24, MEP61 (5′-TCTCAATTCTAgAATTATTCCTGTATATTGC-3′) and MEP24, and MEP62 (5′-TTTTTCTagaAAATTGTTTATCAGTGTGAAAAATC-3′) and MEP24, respectively, and substituted for the XbaI-XhoI fragment in pMEP2ΔP1 to generate pMEP2ΔP3, pMEP2ΔP4, pMEP2ΔP6, and pMEP2ΔP7. To construct pMEP2ΔP5, a distal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −1478 to −435) was amplified with the primer pair MEP44 and MEP60 (5′-GGGGTAAATCTagaGTGGTTAAAAGGATATCC-3′) and used to replace the distal MEP2 promoter fragment in pMEP2ΔP1. For pMEP2MP1, in which the GATA sequence centered at position −208 is replaced by an XbaI site, a distal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −1478 to −210), amplified with the primers MEP44 and MEP64 (5′-GATTTTTCACACTctagAACAATTTCCCAG-3′), and a proximal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −205 to −5), amplified with the primers MEP63 (5′-CTGGGAAATTGTTctagAGTGTGAAAAATC-3′) and MEP24, were fused at the introduced XbaI site and substituted for the wild-type MEP2 promoter in pMEP2G6. For pMEP2MP2, in which the GATA sequence centered at position −266 is replaced by a BglII site, a distal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −1478 to −269), amplified with the primers MEP44 and MEP66 (5′-GAAAAAAATATAGATctGCAATATACAGG-3′), and a proximal MEP2 promoter fragment (positions −266 to −5), amplified with the primers MEP65 (5′-CCTGTATATTGCagATCTATATTTTTTTC-3′) and MEP24, were fused and substituted for the wild-type MEP2 promoter in pMEP2G6. To introduce both mutations into the MEP2 promoter, the same proximal MEP2 promoter fragment was amplified from pMEP2MP1, fused with the distal MEP2 promoter fragment, and substituted for the wild-type MEP2 promoter in pMEP2G6 to create pMEP2MP3. pMEP2G7 was generated by substituting the C. albicans-adapted SAT1 (caSAT1) marker (22) for the URA3 marker in pMEP2G2 to allow the expression of the GFP-tagged MEP2 gene in the wild-type strain SC5314 and the gln3Δ and gat1Δ mutants derived from it. Similarly, the URA3 marker was replaced by the caSAT1 marker in the previously described plasmid pMEP1G1 (2) to obtain pMEP1G4, which was used to express a GFP-tagged MEP1 gene in the same strains. To express the wild-type MEP2 gene from wild-type and mutated MEP2 promoters, a PstI-SacI fragment from pMEP2K1 (2) was substituted for the PstI-SacI fragments in plasmids pMEP2G6, pMEP2ΔP5, pMEP2ΔP6, pMEP2MP1, pMEP2MP2, and pMEP2MP3 (see Fig. 1), thereby generating pMEP2K13, pMEP2ΔP5A, pMEP2ΔP6A, pMEP2MP1A, pMEP2MP2A, and pMEP2MP3A, respectively, in which GFP-tagged MEP2 is replaced by wild-type MEP2.

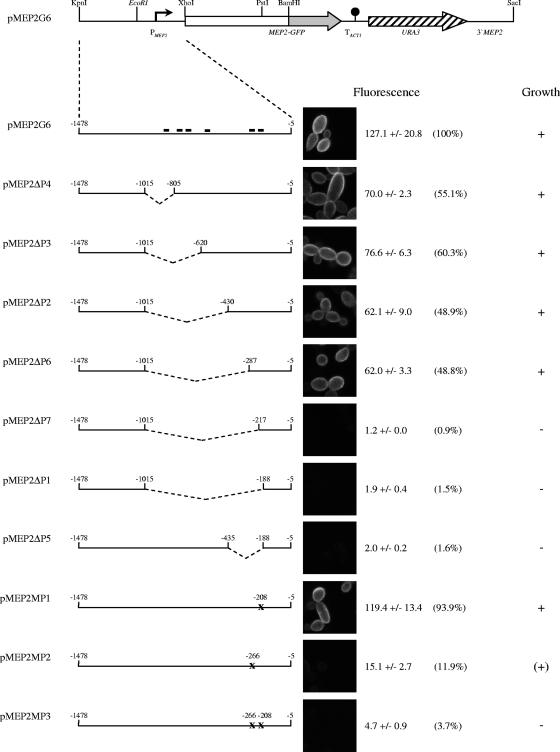

FIG. 1.

MEP2 promoter analysis. The structure of the insert of plasmid pMEP2G6, which contains a GFP-tagged MEP2 gene under the control of the wild-type MEP2 promoter, is shown on top. The MEP2 and GFP coding regions are represented by the white box and the gray arrow, respectively, the transcription termination sequence of the ACT1 gene (TACT1) by the filled circle, and the URA3 selection marker by the hatched arrow. MEP2 upstream and downstream sequences are represented by the solid lines, and the MEP2 promoter (PMEP2) is symbolized by the bent arrow. Relevant restriction sites are shown. The polymorphic EcoRI site, which is present only in the MEP2-1 allele, is highlighted in italics. Enlarged representations of the MEP2 regulatory region with the introduced deletions and mutations are shown below, and the names of the corresponding plasmids are indicated to the left. The extents of MEP2 promoter sequences contained in the various plasmids are given. Internal deletions are indicated by the dashed lines. The locations of GATAA sequences within 1 kb upstream of the MEP2 start codon are indicated by the short black bars in the wild-type promoter. The mutations of the GATAA sequences centered at positions −266 and −208 are marked by an X. The phenotypes conferred by the various constructs upon integration into mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants are shown to the right. Fluorescence of the cells was observed after 6 h of growth at 30°C in liquid SLAD medium. The fluorescence micrographs show representative cells, and the mean levels of fluorescence of the two independently constructed reporter strains (± standard deviations) as measured by flow cytometry are given. The percentages in parentheses are with respect to the fluorescence of the wild-type MEP2 promoter, which was set to 100%. Growth of the strains at limiting ammonium concentrations was as follows: +, wild-type growth; (+), weak growth; −, no growth (see also Fig. 2A).

(ii) Plasmids containing wild-type or hyperactive MEP2 alleles under the control of the ADH1 promoter.

To express MEP2 from the ADH1 promoter in strain SC5314 and the gln3Δ mutants, an XhoI-BglII fragment from plasmid pMEP2K2 containing the MEP2 coding region (2) was cloned between the ADH1 promoter and the ACT1 transcription termination sequence of plasmid pADH1E1, which contains the caSAT1 selection marker and flanking ADH1 sequences for integration into the ADH1 locus (21), generating pMEP2E4. Similarly, an XhoI-BglII fragment from pMEP2ΔC2K2 containing the hyperactive MEP2ΔC440 allele (2) was inserted in the same way in pADH1E1 to obtain pMEP2ΔC2E2. A control plasmid, pADH1G4, contains the GFP gene instead of MEP2 (Y.-N. Park and J. Morschhäuser, unpublished).

(iii) MEP2, GAT1, and GLN3 deletion and reinsertion constructs.

A GLN3 deletion construct was generated in the following way. An ApaI-XhoI fragment containing GLN3 upstream sequences from positions −204 to +6 with respect to the start codon was amplified from the genomic DNA of C. albicans strain SC5314 with the primer pair GLN1 (5′-ATAACgggCCCTACCTAGAGGAATAAGTTC-3′) and GLN2 (5′-GACTGACTATTCGctcgAGTCATTTGTCCC-3′). A SacII-SacI fragment downstream of GLN3 from positions +2025 to +2293 was amplified with the primers GLN3 (5′-GGGGATTATAAGGccgcGGATTGGTTGAAG-3′) and GLN4 (5′-GTCGTTTAGGTCACgaGCTCCACGAGATG-3′). The GLN3 upstream and downstream fragments were substituted for the OPT1 flanking sequences in pOPT1M3 (22) to result in pGLN3M2, in which the GLN3 coding region from positions +7 to +2024 (23 bp before the stop codon) is replaced by the SAT1 flipper (see Fig. 3A). For reintegration of an intact GLN3 copy into gln3Δ single or gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants, an ApaI-BamHI fragment containing the complete GLN3 open reading frame and upstream sequences was amplified with the primers GLN1 and GLN5 (5′-ATATTggaTCCTAGAGTTTGCAAACACGTAC-3′) and cloned together with a BglII-SalI fragment from pCBF1M4 containing the ACT1 transcription termination sequence (3) into ApaI/XhoI-digested pGLN3M2 to create pGLN3K1 (see Fig. 3B).

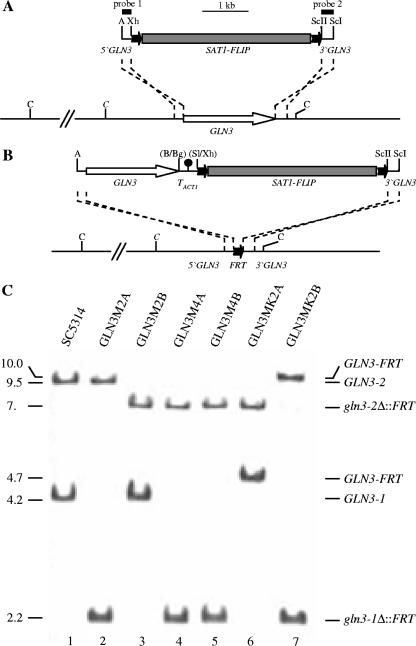

FIG. 3.

Construction of gln3Δ mutants and complemented strains. (A) Structure of the deletion cassette from plasmid pGLN3M2 (top), which was used to delete the GLN3 open reading frame, and genomic structure of the GLN3 locus in strain SC5314 (bottom). The GLN3 coding region is represented by the white arrow and the upstream and downstream regions by the solid lines. Details of the SAT1 flipper (gray rectangle bordered by FRT sites [black arrows]) have been presented elsewhere (22). The 34-bp FRT sites are not drawn to scale. The probes used for Southern hybridization analysis of the mutants are indicated by the black bars. (B) Structure of the DNA fragment from pGLN3K1 (top), which was used for reintegration of an intact GLN3 copy into one of the disrupted GLN3 loci in the gln3Δ single and gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants (bottom). Only relevant restriction sites are given in panels A and B, as follows: A, ApaI; B, BamHI; Bg, BglII; C, ClaI; ScI, SacI; ScII, SacII; Sl, SalI; and Xh, XhoI. Sites shown in parentheses were destroyed by the cloning procedure. The ClaI site marked in italics is present only in the GLN3-1 allele. (C) Southern hybridization of ClaI-digested genomic DNA of the wild-type strain SC5314 and gln3Δ mutants and complemented strains with the GLN3-specific probe 1. The sizes of the hybridizing fragments (in kb) are given on the left side of the blot, and their identities are indicated on the right. Insertion of the SAT1 flipper into either of the two GLN3 alleles of the parental strain SC5314 (lane 1) and subsequent FLP-mediated excision of the cassette produced the heterozygous mutants GLN3M2A and GLN3M2B (lanes 2 and 3). Insertion of the SAT1 flipper into the remaining wild-type GLN3 alleles, followed by recycling of the SAT1 flipper cassette, gave rise to the homozygous gln3Δ mutants GLN3M4A and GLN3M4B (lanes 4 and 5). An intact GLN3 copy was reintroduced into the gln3Δ mutants with the help of the SAT1 flipper, which was subsequently excised again to produce the complemented strains GLN3MK2A and GLN3MK2B (lanes 6 and 7).

To generate a GAT1 deletion construct, an ApaI-XhoI fragment containing GAT1 upstream sequences from positions −429 to −69 was amplified with the primer pair GAT1 (5′-CCGATAACAATAAgggCCCTCCCAATCAG-3′) and GAT2 (5′-TGTAGTGGCTGTGctCGAGTTAAGCTGC-3′), and a SacII-SacI GAT1 downstream fragment from positions +2003 to +2559 was amplified with the primers GAT5 (5′-GAGGGTTCCgcggCTAGTGGAGTCAATACATC-3′) and GAT6 (5′-TGACAGAGGAGctcATGATTGGGTTGGATCTG-3′). The GAT1 upstream and downstream fragments were substituted for the GLN3 flanking sequences in pGLN3M2 to result in pGAT1M2, in which the GAT1 coding region from positions −68 to +2002 (63 bp before the stop codon) is replaced by the SAT1 flipper. To delete MEP2 in the wild-type strain SC5314, the caSAT1 selection marker was substituted for the URA3 marker in the previously described pMEP2M2 plasmid (2), generating pMEP2M5.

C. albicans transformation.

C. albicans strains were transformed by electroporation (10) with gel-purified inserts from the plasmids described above. Uridine-prototrophic transformants were selected on SD agar plates, and nourseothricin-resistant transformants were selected on YPD agar plates containing 200 μg ml−1 nourseothricin (Werner Bioagents, Jena, Germany), as described previously (22). Single-copy integration of all constructs was confirmed by Southern hybridization.

Isolation of genomic DNA and Southern hybridization.

Genomic DNA from C. albicans strains was isolated as described previously (19). Ten micrograms of DNA was digested with appropriate restriction enzymes, separated on a 1% agarose gel, and after ethidium bromide staining, transferred by vacuum blotting onto a nylon membrane and fixed by UV cross-linking. Southern hybridization with enhanced-chemiluminescence-labeled probes was performed with the Amersham ECL direct nucleic acid labeling and detection system (GE Healthcare, Braunschweig, Germany) according to the instructions of the manufacturer.

RNA isolation and Northern hybridization.

Total RNA was isolated from log-phase cultures of the C. albicans strains in liquid synthetic low ammonium dextrose (SLAD) medium by the hot acidic phenol method (1). The MEP2 transcript was detected by Northern hybridization with an XhoI-BglII fragment from plasmid pMEP2K2 (2) containing the complete MEP2 coding sequence as the probe. The probe was labeled with the Amersham Rediprime II random prime labeling system (GE Healthcare), and Northern hybridization was performed using standard protocols (1).

Fluorescence microscopy and flow cytometry.

Fluorescence microscopy was performed with a Zeiss LSM 510 inverted confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a Zeiss Axiovert 100 microscope. Imaging scans were acquired with an argon laser with a wavelength of 488 nm and corresponding filter settings for GFP and parallel transmission images. The cells were observed with a 63× immersion oil objective. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis was performed with a FACSCalibur cytometry system equipped with an argon laser emitting at 488 nm (Becton Dickinson, Heidelberg, Germany). Fluorescence was measured on the FL1 fluorescence channel equipped with a 530-nm-band-pass filter. Twenty thousand cells were analyzed per sample and were counted at a low flow rate. Fluorescence and forward-scatter data were collected by using logarithmic amplifiers. The mean fluorescence values were determined with CellQuest Pro (Becton Dickinson) software. Strain SC5314, which does not carry GFP, was included as a negative control in all experiments, and the background fluorescence values of this strain (between 1.6 and 3.7 in the various experiments) were subtracted from those of the reporter strains.

RESULTS

Two putative GATA factor binding sites in the MEP2 regulatory region mediate the induction of MEP2 expression in response to nitrogen limitation.

To elucidate how MEP2 expression is regulated, we first identified the sequences in the MEP2 promoter that mediate its induction under limiting nitrogen conditions. For this purpose, we used a GFP-tagged MEP2 gene as a reporter and expressed it under the control of wild-type and mutated MEP2 promoters in mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants. This approach allowed us to monitor the expression of Mep2p by observing both the fluorescence of the cells and the capacity of the tagged ammonium permease to restore growth of the double mutants at low ammonium concentrations. The reporter constructs were designed such that they could be integrated at the original MEP2 locus (Fig. 1), since it has been shown that the integration of C. albicans genes at a different genomic site may affect their expression (11). Replacement of the resident wild-type promoter by the mutated MEP2 promoters was verified by Southern hybridization analysis (data not shown), and two independent transformants containing a single copy of the reporter construct were used for further analysis in each case (see Table 1 for strain descriptions).

As reported previously (2), expression of the MEP2-GFP fusion from the wild-type MEP2 promoter resulted in strong fluorescence of the cells in SLAD medium and wild-type growth on plates containing limiting ammonium concentrations (Fig. 1 and 2A). Deletion of MEP2 upstream sequences ranging from positions −1014 up to −288 with respect to the start codon (ΔP2, ΔP3, ΔP4, ΔP6) reduced MEP2 expression by only about 50% and did not detectably affect growth at limiting ammonium concentrations, but deletion of additional sequences to positions −218 or −189 (ΔP1, ΔP7) abolished MEP2 expression, and transformants carrying these fusions behaved like mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants. A shorter deletion ranging from positions −434 to −189 (ΔP5) produced the same phenotype, suggesting that sequences within this region control MEP2 induction in response to nitrogen limitation. Inspection of the DNA sequence of this region revealed that it contained two putative binding sequences for GATA transcription factors (GATAA) (17) located at positions −264 to −268 and −206 to −210 on the antisense strand. To test whether these sequences are involved in the regulation of MEP2 expression, we changed the GATAA sequence centered at −266 to GATCT and the GATAA sequence centered at −208 to CTAGA in the full-length MEP2 promoter. Whereas mutation of the GATAA sequence at −208 alone (MP1) had no effect, mutation of the GATAA sequence at −266 (MP2) strongly reduced MEP2 expression, and transformants carrying this construct showed only weak growth at limiting ammonium concentrations. Mutation of both GATAA sequences (MP3) reduced MEP2 expression almost to background values, and the corresponding transformants were unable to grow at low ammonium concentrations, like mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants. These results demonstrated that these GATAA sequences are important for MEP2 expression and that GATA transcription factors may be involved in the induction of MEP2 under nitrogen starvation conditions. There are a number of additional GATAA sequences located at more distal sites in the MEP2 upstream region (Fig. 1), but the results of our promoter deletion and mutation analyses indicate that these sequences are neither required nor sufficient for MEP2 expression.

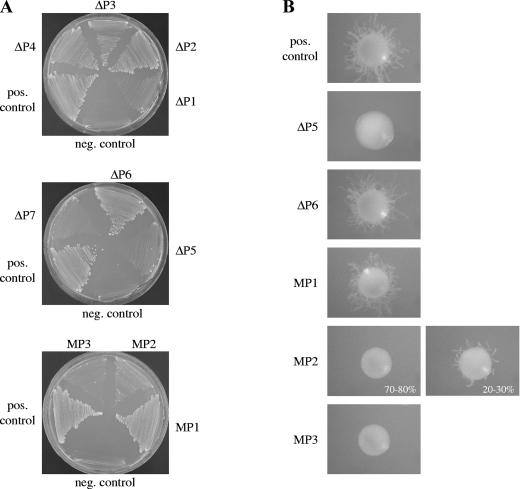

FIG. 2.

(A) Growth of mep1Δ mep2Δ double mutants expressing a GFP-tagged MEP2 gene from the wild-type MEP2 promoter and derivatives containing the indicated deletions or mutations. The strains were grown for 4 days at 30°C on SD plates containing 1 mM ammonium. The following strains were used: MEP12M6A and -B (negative [neg.] control), MEP12MG6A and -B (positive [pos.] control), MEP12MG6ΔP1A and -B (ΔP1), MEP12MG6ΔP2A and -B (ΔP2), MEP12MG6ΔP3A and -B (ΔP3), MEP12MG6ΔP4A and -B (ΔP4), MEP12MG6ΔP5A and -B (ΔP5), MEP12MG6ΔP6A and -B (ΔP6), MEP12MG6ΔP7A and -B (ΔP7), MEP12MG6MP1A and -B (MP1), MEP12MG6MP2A and -B (MP2), and MEP12MG6MP3A and -B (MP3). The two independently constructed reporter strains behaved identically, and only one of them is shown in each case. (B) Filamentation of mep2Δ mutants expressing MEP2 from the wild-type MEP2 promoter and derivatives containing the indicated deletions or mutations. The strains were grown for 6 days at 37°C on SLAD plates, and individual representative colonies were photographed. The following strains were used: MEP2MK13A and -B (pos. control), MEP2MK13ΔP5A and -B (ΔP5), MEP2MK13ΔP6A and -B (ΔP6), MEP2MK13MP1A and -B (MP1), MEP2MK13MP2A and -B (MP2), and MEP2MK13MP3A and -B (MP3). Independently constructed strains behaved identically, and only one of them is shown in each case.

MEP2 expression levels correlate with nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth.

Since we had previously shown that the higher expression levels of MEP2 than those of MEP1 are a prerequisite for normal filamentation in response to nitrogen limitation (2), we assessed the effect of reduced Mep2p expression from mutated MEP2 promoters on filamentous growth. For this purpose, MEP2 was expressed from various mutated MEP2 promoters displaying different activities (wild type, ΔP5, ΔP6, MP1, MP2, and MP3) in a mep2Δ background, thus allowing normal ammonium uptake due to the presence of the MEP1 gene (Fig. 2B). As expected, normal Mep2p expression levels, as from the MP1 promoter, resulted in wild-type filamentation. A slight reduction (by about 50%) of Mep2p expression, as from the ΔP6 promoter, also did not detectably affect filamentous growth. However, the strongly (circa eightfold) reduced Mep2p expression levels obtained from the MP2 promoter severely affected the ability of the strains to produce filamentous colonies in response to nitrogen starvation. Most colonies were nonfilamentous, and a minority showed only a weak filamentation. Further reduction of Mep2p expression to nearly background levels, as from the ΔP5 or MP3 promoter, completely abolished filamentous growth. Therefore, nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth directly correlated with Mep2p expression levels.

MEP2 expression is controlled by the GATA factors Gln3p and Gat1p.

In S. cerevisiae, MEP2 expression requires at least one of the two GATA transcription factors Gln3p and Gat1p/Nil1p, which are involved in the transcriptional activation of many nitrogen-regulated genes (16, 18). C. albicans possesses homologues of GLN3 and GAT1 (4, 13), and we investigated whether these transcription factors are involved in the induction of MEP2 expression under limiting nitrogen conditions. For this purpose, we generated two independent series each of gln3Δ single mutants, gat1Δ single mutants, and gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants from the C. albicans wild-type strain SC5314, using the SAT1-flipping strategy (22). The construction of the gln3Δ mutants and complemented strains is documented in Fig. 3, and inactivation of GAT1 in strain SC5314 and in the gln3Δ mutants to create gat1Δ single and gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants, respectively, was performed in an analogous fashion (data not shown).

To investigate whether GLN3 and GAT1 are involved in the induction of Mep2p expression in response to nitrogen limitation, we compared the expression of GFP-tagged Mep2p in the wild-type strain SC5314, the gln3Δ and gat1Δ single mutants, and the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants after the integration of a MEP2-GFP fusion into one of the MEP2 alleles in these strains. The reporter strains were grown in liquid media containing limiting amounts (100 μM) of ammonium, glutamine, proline, or urea, and fluorescence of the cells was measured by flow cytometry. As can be seen in Fig. 4A, in all these media, Mep2p expression was strongly reduced in the gln3Δ and gat1Δ single mutants and was below the detection limit in the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants. These results, which were confirmed by Northern hybridization (Fig. 4C), demonstrated that both GATA transcription factors control MEP2 expression in C. albicans, similarly to their counterparts in S. cerevisiae.

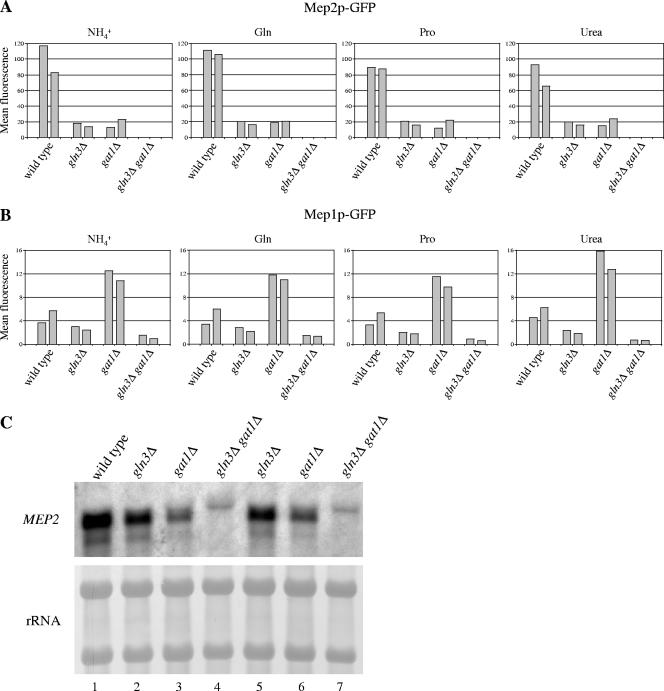

FIG. 4.

GLN3 and GAT1 control ammonium permease expression in C. albicans. (A and B) Expression of GFP-tagged Mep2p (A) and Mep1p (B) in the wild type, gln3Δ and gat1Δ single mutants, and gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants in liquid media containing limiting concentrations (100 μM) of the indicated nitrogen sources. Overnight cultures of the reporter strains in SD-Pro medium were diluted 50-fold in the test media and grown for 6 h at 30°C. The fluorescence of the cells was measured by flow cytometry. The first columns show the results obtained with the A series, and the second columns show the results obtained with the B series of the reporter strains (see Table 1). Note that the scales of the y axis are different for Mep2p-GFP and Mep1p-GFP. (C) Detection of MEP2 mRNA by Northern hybridization with a MEP2-specific probe. Overnight cultures of the wild-type strain SC5314 (lane 1), the gln3Δ mutants GLN3M4A (lane 2) and GLN3M4B (lane 5), the gat1Δ mutants GAT1M4A (lane 3) and GAT1M4B (lane 6), and the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants Δgln3GAT1M4A (lane 4) and Δgln3GAT1M4B (lane 7) in SD-Pro medium were diluted 50-fold in liquid SLAD medium, and RNA was isolated after 6 h of growth at 30°C. The MEP2 transcript is absent from the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants; the faint band of slightly higher molecular weight than that of MEP2 seen in these and all other strains represents a cross-hybridizing transcript.

To test whether the GATA transcription factors also regulate MEP1, the expression of GFP-tagged Mep1p in the wild-type strain SC5314 and the gln3Δ, gat1Δ, and gln3Δ gat1Δ mutants was monitored under the same conditions (Fig. 4B). In agreement with our previous results (2), Mep1p was expressed at much lower levels than Mep2p in the wild-type background (roughly 20-fold less as measured by flow cytometry). Compared with that of the wild type, Mep1p expression was slightly reduced in the gln3Δ mutants but elevated in the gat1Δ mutants. Only very low levels of Mep1p expression were observed in the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants. Therefore, both Gln3p and Gat1p also regulate MEP1 expression.

The GATA factor Gln3p regulates nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth in C. albicans.

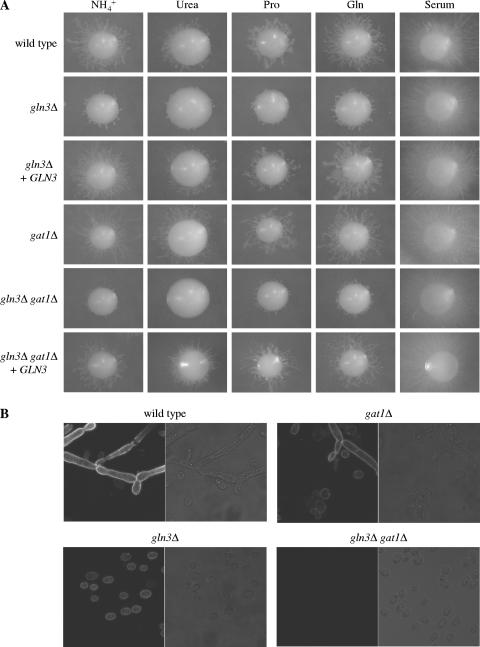

We then tested the growth of the strains on agar plates containing limiting concentrations of different nitrogen sources (Fig. 5A). All mutants grew as well as the wild-type strain SC5314 on SLAD plates, indicating that the reduced Mep1p expression levels in the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants still allowed sufficient ammonium uptake for normal growth. However, the gln3Δ mutants showed delayed and strongly reduced filamentation on SLAD plates as well as on plates containing 100 μM urea, proline, glutamate, glutamine, or histidine as the sole nitrogen source, conditions under which MEP2 is required for filamentous growth (2). While wild-type colonies started to produce filaments after about 3 days of incubation, no filamentous colonies of gln3Δ mutants were seen at day 4, and fewer and shorter filaments than in the wild type were observed after 6 days (Fig. 5A and data not shown). In contrast, deletion of GAT1 did not affect filamentation on these plates, and gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants behaved like the gln3Δ single mutants, except on urea plates, on which no filamentation was observed in the double mutants. Reintroduction of GLN3 into the gln3Δ single and the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants restored filamentation to wild-type levels, confirming that the filamentous growth defect of the mutants was due to GLN3 inactivation. No filamentation defect of the mutants was observed on plates containing serum, indicating that GLN3 is specifically required for normal filamentous growth in response to nitrogen limitation.

FIG. 5.

(A) GLN3 is required for the normal filamentous growth of C. albicans in response to nitrogen limitation. YPD precultures of the strains were appropriately diluted and spread on SD agar plates containing the indicated nitrogen sources at a concentration of 100 μM or on agar plates containing serum as an inducer of filamentous growth. Individual colonies were photographed after 6 days of incubation at 37°C. The following strains were used: SC5314 (wild type), GLN3M4A and -B (gln3Δ), GLN3MK2A and -B (gln3Δ + GLN3), GAT1M4A and -B (gat1Δ), Δgln3GAT1M4A and -B (gln3Δ gat1Δ), and Δgln3GAT1MK2A and -B (gln3Δ gat1Δ + GLN3). Independently constructed mutants and complemented strains behaved identically, and only one of them is shown in each case. (B) Expression of GFP-tagged Mep2p in the wild-type (strains SCMEP2G7A and -B), gat1Δ (strains Δgat1MEP2G7A and -B), gln3Δ (strains Δgln3MEP2G7A and -B), and gln3Δ gat1Δ (strains Δgln3Δgat1MEP2G7A and -B) backgrounds on SLAD plates. The pictures show fluorescence and corresponding phase-contrast micrographs of cells taken from colonies of the reporter strains grown for 6 days at 37°C.

To investigate whether the filamentation phenotype of the mutants correlated with Mep2p expression on solid media, we observed the expression of GFP-tagged Mep2p in the corresponding reporter strains on SLAD plates. As in liquid SLAD medium, Mep2p expression was strongly reduced in both the gln3Δ and gat1Δ single mutants and was undetectable in the gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants also on filamentation-inducing solid medium (Fig. 5B). Therefore, the reduced MEP2 expression in strains lacking GLN3 correlated with their filamentation defect. In contrast, deletion of GAT1 did not affect filamentous growth under these conditions, despite the fact that MEP2 expression was similarly reduced in gln3Δ and gat1Δ mutants.

Inactivation of GAT1 activates MEP2-independent filamentation pathways.

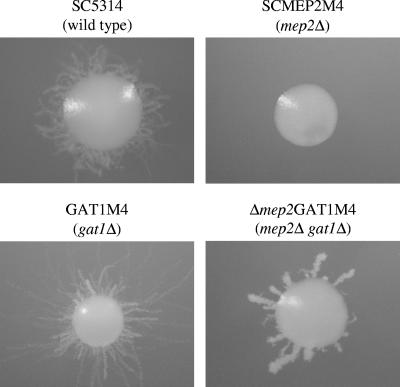

The ability of the gat1Δ mutants to filament under limiting nitrogen conditions despite strongly reduced Mep2p expression levels suggested that nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth may not depend on the Mep2p ammonium permease in the prototrophic wild-type strain SC5314, in contrast to its auxotrophic derivative CAI4, which was the parent of our mep2Δ mutants (2). To exclude the possibility that inappropriate URA3 expression levels at the MEP2 locus were responsible for the filamentation defect of the mep2Δ mutants, we inserted the URA3 gene back at its original locus in the two independently constructed mep2Δ mutants MEP2M4A and MEP2M4B as well as in our copy of strain CAI4. The resulting mep2Δ mutants MEP2M4R1A and MEP2M4R1B exhibited the same filamentation defect as our previously constructed mep2Δ mutants, whereas the wild-type control strains CAI4R1A and CAI4R1B showed normal filamentation (data not shown). As a further test for the requirement of Mep2p for nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth in C. albicans, we deleted MEP2 in the prototrophic wild-type strain SC5314 using the SAT1-flipping strategy. Two independent mep2Δ mutants were generated, and both exhibited the same filamentous growth defect on SLAD plates as our previously constructed mep2Δ mutants (Fig. 6, top panels). These results confirmed that Mep2p controls nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth in C. albicans.

FIG. 6.

Inactivation of GAT1 results in MEP2-independent filamentation. The indicated strains were grown for 6 days at 37°C on SLAD plates, and individual colonies were photographed. Independently constructed mutants behaved identically, and only one of them is shown in each case.

We hypothesized that the absence of a functional Gat1p protein might result in the activation of filamentation-inducing signaling pathways that do not require high MEP2 expression levels or that are even independent of Mep2p. To test this hypothesis, we deleted GAT1 from the two mep2Δ mutants constructed from strain SC5314. Strikingly, both independently generated mep2Δ gat1Δ double mutants regained the ability to produce filaments under nitrogen starvation conditions, albeit not to wild-type levels (Fig. 6). Therefore, the ability of the gat1Δ mutants to produce filaments normally despite strongly reduced Mep2p expression levels can be explained by the activation of additional signaling pathways which can induce filamentation in response to nitrogen starvation, even in the absence of Mep2p.

Forced MEP2 expression bypasses the requirement of GLN3 for filamentous growth.

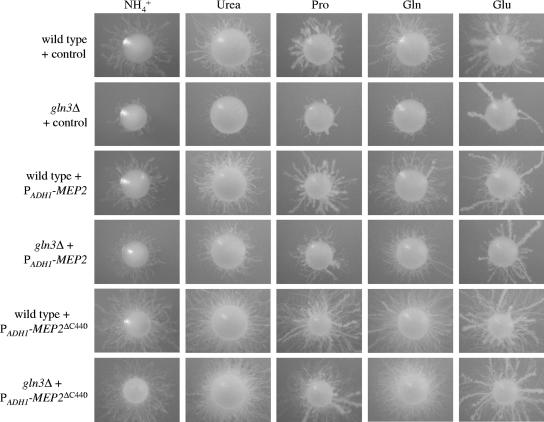

If the failure to express MEP2 at appropriate levels was the cause of the filamentous growth defect of the gln3Δ mutants, forced expression of MEP2 from a different promoter should restore normal filamentation. To test this hypothesis, we expressed MEP2 under the control of the ADH1 promoter in the wild-type strain SC5314 and in the gln3Δ mutants. In addition, we also expressed the hyperactive MEP2ΔC440 allele, which is strongly overexpressed, presumably due to enhanced transcript stability (2), from the ADH1 promoter. As a control, the GFP gene was integrated instead of MEP2 in an identical fashion.

Expression of an additional MEP2 copy from the ADH1 promoter had no detectable effect on filamentation of the wild-type strain SC5314, but expression of the hyperactive MEP2ΔC440 allele from the ADH1 promoter in the same strain resulted in a hyperfilamentous phenotype, as previously reported for strain CAI4 expressing the MEP2ΔC440 allele from the native MEP2 promoter (2). Forced expression of MEP2 from the ADH1 promoter partially rescued the filamentation defect of the gln3Δ mutants, and expression of the hyperactive MEP2ΔC440 allele resulted in the same hyperfilamentous phenotype as in the wild-type background (Fig. 7). Therefore, forced expression of MEP2 overcomes the filamentous growth defect caused by GLN3 inactivation.

FIG. 7.

Forced expression of MEP2 overcomes the filamentous growth defect of gln3Δ mutants. YPD precultures of the strains were appropriately diluted and spread on SD agar plates containing the indicated nitrogen sources at a concentration of 100 μM. Individual colonies were photographed after 6 days of incubation at 37°C. The following strains were used: SCADH1G4A and -B (wild type + control), Δgln3ADH1G4A and -B (gln3Δ + control), SCMEP2E4A and -B (wild type + PADH1-MEP2), Δgln3MEP2E4A and -B (gln3Δ + PADH1-MEP2), SCMEP2ΔC2E2A and -B (wild type + PADH1-MEP2ΔC440), and Δgln3MEP2ΔC2E2A and -B (gln3Δ + PADH1-MEP2ΔC440). Independently constructed mutants and complemented strains behaved identically, and only one of them is shown in each case.

DISCUSSION

The ammonium permease Mep2p plays a major role in nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth of C. albicans. An important aspect of the ability of Mep2p to stimulate filamentation in response to nitrogen limitation is the much higher expression levels of Mep2p than those of Mep1p, since reduced MEP2 expression from the MEP1 promoter abolished filamentous growth (2). The filamentous growth defect of strains expressing MEP2 from the MEP1 promoter in a mep1Δ mep2Δ background was not caused simply by the slower growth of these strains on SLAD plates due to inefficient ammonium uptake, since the defect was also observed when the PMEP1-MEP2 fusion was expressed in mep2Δ single mutants, which can grow at wild-type rates because of the presence of an intact MEP1 allele (K. Biswas and J. Morschhäuser, unpublished results). A correlation between filamentous growth and Mep2p expression levels was also found in the present study when MEP2 was expressed from mutated MEP2 promoters with different levels of activity. Obviously, expressing Mep2p at appropriate levels is a prerequisite for C. albicans to be able to induce the switch from yeast to filamentous growth in response to nitrogen starvation. Therefore, we set out to investigate how the expression of MEP2 is regulated. We found that two putative GATA factor binding sites in the MEP2 promoter are essential for the upregulation of MEP2 under limiting nitrogen conditions, pointing to the involvement of GATA transcription factors in the regulation of MEP2 expression. While mutation of the GATAA sequence centered at position −208 alone had no significant effect, the same mutation almost completely abolished MEP2 expression when combined with a mutation of the GATAA sequence centered at position −266, which by itself already reduced MEP2 expression very strongly. Since a single GATAA sequence is essential but not adequate for nitrogen regulation in S. cerevisiae (17), GATAA sequences located further upstream or other regulatory sequences may also act together with the −266 site.

Our results demonstrate that both of the GATA transcription factors Gln3p and Gat1p are required for full MEP2 expression, since deletion of either GLN3 or GAT1 strongly reduced MEP2 expression under all conditions tested and no MEP2 expression was detected in the absence of both transcription factors. In S. cerevisiae, both Gln3p and Gat1p also promote high-level expression of MEP2, but the contribution of each factor depends on the available nitrogen source (18).

The gln3Δ mutants were also severely impaired in filamentous growth under nitrogen starvation conditions, a phenotype that correlated well with the reduced MEP2 expression levels in these mutants. Therefore, the inability of the gln3Δ mutants to induce MEP2 expression at appropriate levels may be responsible for their filamentation defect, and we hypothesized that forced MEP2 expression from a different promoter should bypass the filamentous growth defect of gln3Δ mutants. In fact, when a MEP2 copy was expressed from the ADH1 promoter in the gln3Δ mutants, filamentation was partially restored, and forced overexpression of a hyperactive MEP2 allele completely rescued the filamentation defect of the gln3Δ mutants and resulted in a hyperfilamentous phenotype, as in a wild-type background. S. cerevisiae gln3Δ mutants are also defective in pseudohyphal differentiation, but expression of MEP2 from a heterologous, inducible promoter did not restore filamentation, indicating that Gln3p has additional targets that are critical for pseudohyphal growth in S. cerevisiae (16). Our results do not exclude the possibility that, in C. albicans, Gln3p has targets in addition to MEP2 that are normally required for the induction of filamentous growth in response to nitrogen starvation, but the expression of the hyperactive MEP2 allele bypasses the need to activate these pathways. A similar observation was made previously, when we found that expression of the hyperactive MEP2 allele from its own promoter overcame the filamentation defect of cph1Δ and efg1Δ single mutants but not that of cph1Δ efg1Δ double mutants, although both transcription factors, which are at the end of a mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade and a cyclic-AMP-dependent signaling pathway, respectively, are normally required for nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth of C. albicans (2).

Considering that MEP2 expression in the gat1Δ mutants was reduced to levels similar to those in gln3Δ mutants, it was surprising that gat1Δ mutants had no obvious filamentation defect. However, this result is in agreement with an independent study in which it was reported that the deletion of GAT1 from C. albicans did not affect filamentation (13). It is possible that the reduced MEP2 expression levels seen in both mutants are still sufficient to induce filamentation, but other targets which are also required for filamentous growth are affected by the inactivation of GLN3 but not of GAT1. In fact, we found that the expression levels of GFP-tagged Mep2p in the gln3Δ and gat1Δ mutants were still higher (roughly twofold) than those in strains expressing the MEP2-GFP fusion construct from the MEP1 promoter, which were not sufficient for filamentation (data not shown). In addition, we found that, in the absence of the Gat1p transcription factor, C. albicans activates signaling pathways that can partially bypass the requirement of Mep2p for filamentation. Wild-type filamentation in the gat1Δ mutants still depends on Gln3p activity, as gln3Δ gat1Δ double mutants exhibited the same strong filamentation defect as gln3Δ single mutants. Interestingly, work in Bill Fonzi's group has recently demonstrated that GLN3 expression is negatively regulated by Gat1p in C. albicans (12). Increased expression of GLN3 in gat1Δ mutants may therefore be responsible for the increased MEP1 (but not MEP2) expression levels seen in these mutants and may also result in the activation of Gat1p-independent pathways that induce filamentation despite reduced MEP2 expression.

In summary, our results demonstrate that, by placing MEP1 and MEP2 under the control of the GATA transcription factors Gln3p and Gat1p, C. albicans ensures that the expression of these ammonium permeases is induced when the preferred nitrogen source, ammonium, is present at low concentrations or absent. The signaling activity of Mep2p then also induces morphogenesis when ammonium levels remain limiting, despite transporter-mediated uptake, allowing the fungus to adjust its growth mode to environmental conditions.

Acknowledgments

We thank Bill Fonzi and Fritz Mühlschlegel for the gift of C. albicans strains SC5314 and CAI4, Neil Clancy for providing plasmid pUR3 containing the C. albicans URA3 gene, and Narayan Subramanian for help with the Northern hybridization experiments. Sequence data for Candida albicans was obtained from the Candida Genome Database (http://www.candidagenome.org/).

This study was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG grant MO 846/4).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 16 March 2007.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ausubel, F., R. Brent, R. Kingston, D. Moore, J. Seidman, J. Smith, and K. Struhl. 1989. Current protocols in molecular biology. John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, NY.

- 2.Biswas, K., and J. Morschhäuser. 2005. The Mep2p ammonium permease controls nitrogen starvation-induced filamentous growth in Candida albicans. Mol. Microbiol. 56:649-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biswas, K., K. J. Rieger, and J. Morschhäuser. 2003. Functional characterization of CaCBF1, the Candida albicans homolog of centromere binding factor 1. Gene 323:43-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braun, B. R., M. van Het Hoog, C. d'Enfert, M. Martchenko, J. Dungan, A. Kuo, D. O. Inglis, M. A. Uhl, H. Hogues, M. Berriman, M. Lorenz, A. Levitin, U. Oberholzer, C. Bachewich, D. Harcus, A. Marcil, D. Dignard, T. Iouk, R. Zito, L. Frangeul, F. Tekaia, K. Rutherford, E. Wang, C. A. Munro, S. Bates, N. A. Gow, L. L. Hoyer, G. Köhler, J. Morschhäuser, G. Newport, S. Znaidi, M. Raymond, B. Turcotte, G. Sherlock, M. Costanzo, J. Ihmels, J. Berman, D. Sanglard, N. Agabian, A. P. Mitchell, A. D. Johnson, M. Whiteway, and A. Nantel. 2005. A human-curated annotation of the Candida albicans genome. PLoS Genet. 1:36-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown, A. J., and N. A. Gow. 1999. Regulatory networks controlling Candida albicans morphogenesis. Trends Microbiol. 7:333-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ernst, J. F. 2000. Transcription factors in Candida albicans—environmental control of morphogenesis. Microbiology 146:1763-1774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fonzi, W. A., and M. Y. Irwin. 1993. Isogenic strain construction and gene mapping in Candida albicans. Genetics 134:717-728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gillum, A. M., E. Y. Tsay, and D. R. Kirsch. 1984. Isolation of the Candida albicans gene for orotidine-5′-phosphate decarboxylase by complementation of S. cerevisiae ura3 and E. coli pyrF mutations. Mol. Gen. Genet. 198:179-182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gimeno, C. J., P. O. Ljungdahl, C. A. Styles, and G. R. Fink. 1992. Unipolar cell divisions in the yeast S. cerevisiae lead to filamentous growth: regulation by starvation and RAS. Cell 68:1077-1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Köhler, G. A., T. C. White, and N. Agabian. 1997. Overexpression of a cloned IMP dehydrogenase gene of Candida albicans confers resistance to the specific inhibitor mycophenolic acid. J. Bacteriol. 179:2331-2338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lay, J., L. K. Henry, J. Clifford, Y. Koltin, C. E. Bulawa, and J. M. Becker. 1998. Altered expression of selectable marker URA3 in gene-disrupted Candida albicans strains complicates interpretation of virulence studies. Infect. Immun. 66:5301-5306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liao, W. L., and W. A. Fonzi. 2006. Abstr. 8th Am. Soc. Microbiol. Conf. Candida candidiasis, Denver, CO, abstr. B29.

- 13.Limjindaporn, T., R. A. Khalaf, and W. A. Fonzi. 2003. Nitrogen metabolism and virulence of Candida albicans require the GATA-type transcriptional activator encoded by GAT1. Mol. Microbiol. 50:993-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu, H. 2002. Co-regulation of pathogenesis with dimorphism and phenotypic switching in Candida albicans, a commensal and a pathogen. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 292:299-311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lo, H. J., J. R. Köhler, B. DiDomenico, D. Loebenberg, A. Cacciapuoti, and G. R. Fink. 1997. Nonfilamentous C. albicans mutants are avirulent. Cell 90:939-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lorenz, M. C., and J. Heitman. 1998. The MEP2 ammonium permease regulates pseudohyphal differentiation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. EMBO J. 17:1236-1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Magasanik, B., and C. A. Kaiser. 2002. Nitrogen regulation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Gene 290:1-18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marini, A.-M., S. Soussi-Boudekou, S. Vissers, and B. Andre. 1997. A family of ammonium transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:4282-4293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Millon, L., A. Manteaux, G. Reboux, C. Drobacheff, M. Monod, T. Barale, and Y. Michel-Briand. 1994. Fluconazole-resistant recurrent oral candidiasis in human immunodeficiency virus-positive patients: persistence of Candida albicans strains with the same genotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 32:1115-1118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Odds, F. C. 1988. Candida and candidosis: a review and bibliography. Bailliere Tindall, London, United Kingdom.

- 21.Reuβ, O., and J. Morschhäuser. 2006. A family of oligopeptide transporters is required for growth of Candida albicans on proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 60:795-812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reuβ, O., Å. Vik, R. Kolter, and J. Morschhäuser. 2004. The SAT1 flipper, an optimized tool for gene disruption in Candida albicans. Gene 341:119-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saville, S. P., A. L. Lazzell, C. Monteagudo, and J. L. Lopez-Ribot. 2003. Engineered control of cell morphology in vivo reveals distinct roles for yeast and filamentous forms of Candida albicans during infection. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1053-1060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Whiteway, M., and U. Oberholzer. 2004. Candida morphogenesis and host-pathogen interactions. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7:350-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng, X., and Y. Wang. 2004. Hgc1, a novel hypha-specific G1 cyclin-related protein regulates Candida albicans hyphal morphogenesis. EMBO J. 23:1845-1856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]